Costa Rica! The name generates a sense of excitement and anticipation among international travelers. Among European explorers, the first recorded visitor was Christopher Columbus in 1502. On his fourth trip to the New World, Columbus landed where the port city of Limón is now located. The natives he encountered wore golden disks around their necks. He called this new place “Costa Rica,” meaning “Rich Coast,” because he thought the gold came from there. The gold had actually come from other countries and had been obtained as a trade item from native traders along the coast.

Spanish treasure seekers eventually discovered their error and went elsewhere in their quest for gold. The irony is that Christopher Columbus actually picked the perfect name for this country. The wealth overlooked by the Spaniards is the rich biological diversity that includes more than 505,000 species of plants and wildlife. That species richness is an incredible natural resource that sustains one of the most successful nature tourism industries in the Western Hemisphere. It also provides the basis for a newly evolving biodiversity industry of “chemical prospecting” among plants and creatures, in search of new foods and medicines for humans.

For such a small country, Costa Rica gets much well-deserved international attention and has become one of the most popular nature tourism destinations in the Americas. The lure is not “sun and sand” experiences at big hotels on the country’s beaches; it is unspoiled nature in far-flung nooks and crannies of tropical wildlands that are accessible at rustic, locally owned nature lodges throughout the country.

It is now possible to immerse yourself in the biological wealth of tropical forests during a vacation in Costa Rica. During a two-week visit you may see more than three hundred to four hundred species of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, butterflies, moths, and other invertebrates. Some vacations are planned for rest and relaxation, but who can do that in such a diverse country where there is so much nature to see and experience? In Costa Rica, every day is an adventure, and the marvelous diversity and abundance of wildlife create an enthusiasm for nature that many people have not experienced since childhood.

Costa Rican tourist DeWayne Jackson, photographing a Caligo butterfly.

The ease with which it is possible to travel to Costa Rica and enjoy wildlife in such a pristine setting makes a visitor think it has always been that way. It has not. The appealing travel and tourism conditions are the product of nearly four decades of social, educational, and cultural developments.

There was a time when Costa Rican wildlife was persecuted at every opportunity. Virtually every creature weighing over a pound was shot for its value as meat or for its hide. Wildlife was killed year-round from the time of settlement through the 1960s. Instead of acquiring souvenirs like T-shirts and postcards in those days, Costa Rican visitors in the 1960s found vendors selling boa constrictor hides, caiman-skin briefcases, stuffed caimans, skins of spotted cats, and sea turtle eggs.

To appreciate the abundance of today’s wildlife populations, it is necessary to understand the revolution in wildlife conservation and habitat preservation that has occurred since the 1960s. Dozens of dedicated biologists, politicians, and private citizens have contributed to Costa Rica’s world leadership in tropical forest conservation, wildlife protection, and nature tourism over the past fifty-plus years. This process occurred in five phases: (1) Research, (2) Education, (3) Preservation, (4) Conservation, and (5) Nature Tourism.

One of the earliest advances for Costa Rica’s legacy of conservation was the development of research data on Costa Rica’s plants and wildlife. Without such basic knowledge, there can be little appreciation, respect, or protection for wild species. In 1941, Dr. Alexander Skutch homesteaded property in the San Isidro del General Valley along the Río Peña Blanca. After settling there with his wife, Pamela, Dr. Skutch studied Costa Rica’s birds for more than sixty years and continued to observe them and record their life history in his prolific writings until his passing in 2004.

In 1954, another biologist, Dr. Archie Carr, started epic research. Dr. Carr, from the University of Florida, began a lifelong commitment to the protection and management of the green turtle at Tortuguero. That effort continues to this day, thanks to his son, Dr. David Carr, and the work of the Caribbean Conservation Corporation, which was created in 1959.

Another significant development for Costa Rica’s legacy of leadership in tropical research was the creation of the Tropical Science Center. It was founded in 1962 by Drs. Leslie R. Holdridge, Joseph A. Tosi, and Robert J. Hunter. These three scientists promoted research on tropical ecosystems, land use, and sustainable development. Dr. Gary Hartshorn later joined the staff to add more expertise in the development of tropical forest management strategies. The Tropical Science Center was instrumental in establishing La Selva Biological Field Station and the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve and in preserving Los Cusingos, the forest reserve formerly owned by Dr. Alexander Skutch. That reserve is now managed by the Tropical Science Center.

Another research catalyst for subsequent conservation and land protection was the creation of the Organization for Tropical Studies (OTS) in 1964. The OTS is a consortium of fifty-five universities and educational institutions throughout the Americas. The OTS operates three tropical research field stations—located at La Selva, Palo Verde, and San Vito. Tropical biologists from throughout the world come to these field stations to pursue pioneering studies on taxonomy, ecology, and conservation of tropical ecosystems.

Dr. Dan Janzen teaching an OTS course in 1967. Photo provided courtesy of the Organization for Tropical Studies.

For many decades, people had believed it was necessary to eliminate tropical forests in the name of progress, to create croplands, pastures, and monocultures of exotic trees for the benefit of society. Tropical biologists of the OTS changed the way people viewed tropical forests and helped society realize the infinitely greater ecological, climatic, and economic benefits that can accrue from preserving and managing tropical forests as sustainable resources.

In 1963 the National Science Foundation supported the Advanced Science Seminar in Tropical Biology, which was subsequently adapted by OTS. The OTS initiated a second part of its legacy with field courses in tropical ecology, forestry, agriculture, and land use for undergraduate and graduate students from throughout the Americas. Since its founding, the OTS has conducted more than 200 field courses for at least 3,600 students. For many of these students, including the author, the courses were life-changing experiences. The faculty who taught these courses were some of the most prominent ecologists in the world, including, among others, Drs. Dan Janzen, Mildred Mathias, Carl Rettenmeyer, Frank Barnwell, Rafael Lucas Rodríguez Caballero, Gordon Orions, Roy McDiarmid, Larry Wolf, and Rex Daubenmire.

Another significant source of tropical education and research has been the Tropical Agricultural Center for Research and Education (Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza; CATIE). This center was created in 1942 at Turrialba and was originally known as the Interamerican Institute of Agricultural Science (Instituto Interamericano de Ciencias Agrícolas; IICA). Graduate students come from all over Latin America to study agriculture, forestry, and wildlife management there.

By the 1960s, about 50 percent of Costa Rica’s forests had been cut, and the clearing continued. It became apparent that national programs for protection of the remaining forests and wildlife would be necessary if they were to be preserved into the next century.

Logging in Costa Rica, 1969.

The first wildlife conservation law was decreed on July 20, 1961, and was updated with bylaws on June 7, 1965. These laws and regulations provided for the creation and enforcement of game laws, the establishment of wildlife refuges, the prohibition of commercial sale of wildlife products, the issuance of hunting and fishing licenses, the establishment of fines for violations, and the creation of restrictions on the export and import of wildlife. Complete protection was given to tapirs, manatees, White-tailed Deer does accompanied by fawns, and Resplendent Quetzals. The laws, however, were not enforced.

In 1968, a Costa Rican graduate student, Mario Boza, was inspired by a visit to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. In 1969 a Forestry Protection Law allowed national parks to be established, and Mario Boza was designated as the only employee of the new National Parks Department. He wrote a master plan for the newly designated Poás Volcano National Park as his master’s thesis subject.

In 1970, wildlife laws were still being ignored by poachers, and wildlife continued to disappear. President “Don Pepe” Figueres visited Dr. Archie Carr and graduate student David Ehrenfeld to see the green turtle nesting beaches at Tortuguero. He was considering a proposal to protect the area as a national park. The following account was later written by Dr. David Ehrenfeld (1989):

It was Don Pepe’s first visit to the legendary Tortuguero—we had been watching a green turtle nest, also a first for him. El Presidente, a short, Napoleonic man with boundless energy, was enjoying himself enormously. Both he and Archie were truly charismatic people, and they liked and respected one another. The rest of us went along quietly, enjoying the show. As we walked up the beach towards the boca, where the Río Tortuguero meets the sea, Don Pepe questioned Dr. Carr about the green turtles and their need for conservation. How important was it to make Tortuguero a sanctuary? Just then, a flashlight picked out a strange sight up ahead.

A turtle was on the beach, near the waterline, trailing something. And behind her was a line of eggs which, for some reason, she was depositing on the bare, unprotected sand. We hurried to see what the problem was.

When we got close, it was all too apparent. The entire undershell of the turtle had been cut away by poachers who were after calipee, or cartilage, to dry and sell to the European turtle soup manufacturers. Not interested in the meat or eggs, they had evidently then flipped her back on her belly for sport, to see where she would crawl. What she was trailing was her intestines. The poachers had probably been frightened away by our lights only minutes before.

Dr. Carr, who knew sea turtles better than any human being on earth and who had devoted much of his life to their protection, said nothing. He looked at Don Pepe, and so did I. It was a moment of revelation. Don Pepe was very, very angry, trembling with rage. This was his country, his place. He had risked his life for it fighting in the Cerro de la Muerte. The turtles were part of this place, even part of its name: Tortuguero; … She was home, laying her eggs for the last time.

Don Pepe realized that the ancient turtles, as well as the Costa Rican people, needed a safe place to live and raise their young. The poaching had to end. He declared Tortuguero National Park by executive decree in 1970. The tragic poaching incident with the nesting green turtle was probably the pivotal incident that catalyzed the national parks movement in Costa Rica. Mario Boza served under President Figueres as the National Park Service director from 1970 to 1974. By the end of 1974, the service had grown to an organization of 100 employees with an annual budget of $600,000. A total of 2.5 percent of the country was designated as national parks and reserves.

Rainbow over the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve.

Private preservation efforts also began in the 1970s. Scientists George and Harriet Powell and Monteverde resident Wilford Guindon created the 810-acre Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve. They brought in the Tropical Science Center to own and manage the preserve, which now totals 27,428 acres. The Monteverde Conservation League was subsequently formed to help manage and carry out conservation projects and land acquisition.

In 1984, Dr. Dan Janzen brought more international recognition to Costa Rica when he received the Crafoord Prize in Coevolutionary Ecology from the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences. This is the ecologist’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize. Dr. Janzen received the prize for his pioneering research on entomology and ecology of tropical dry forests. This focused attention on the need for preserving tropical dry forests in the Guanacaste Conservation Area (http://www.acguanacaste.ac.cr).

Oscar Arias was elected president in 1986. He created the Ministry of Energy, Mining, and Natural Resources (MIRENEM) by merging the national land management departments to make them more efficient in managing the nation’s natural resources. That agency is now referred to as the Ministry of Environment and Energy (Ministerio del Ambiente y Energía; MINAE).

Since then, Costa Rica’s national system of parks and reserves has continued to grow and mature. It now consists of 161 protected areas, including twenty-five national parks. Those areas total 3,221,635 acres—almost 26 percent of the country’s land area. More information on the national park system can be found at www.costarica-nationalparks.com.

Dr. Rodrigo Gámez, parataxonomist and director general of INBIO.

As the national park system grew and encompassed more life zones, it became clear to ecological visionaries like Dr. Dan Janzen and Dr. Rodrigo Gámez Lobo that they had an opportunity to take another bold step that would place them in a world-leadership role for conservation of biological diversity and creation of economic benefits to society from that biological diversity. They created the National Biodiversity Institute (Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad; INBIO). Dr. Gámez Lobo became the first director of INBIO and continues his leadership as president of INBIO. The ambitious goal of this institute was to collect, identify, and catalog all of the living species in Costa Rica. Estimated at 505,000 species, this figure includes 882 birds, 236 mammals, 228 reptiles, 178 amphibians, 360,000 insects, and 10,000 plants. This represents about 5 percent of the world’s species. So far, about 90,000 of those species have been described, and INBIO’s collections include 3.5 million specimens.

Following the creation of INBIO, MIRENEM developed a national system of “conservation areas” in 1990. This is referred to as SINAC (Sistema Nacional de Areas de Conservación). Eleven conservation areas were established. Personnel in the fields of wildlife, forestry, parks, and agriculture teamed up to manage the national parks and wildlands in each conservation area. Their goal is the conservation of Costa Rica’s biodiversity for nondestructive use by Costa Ricans and the world populace. This national scale of ecosystem-based management predated efforts in more “developed” countries by years.

Beginning in the mid-1980s, and concurrent with the conservation phase, the value of Costa Rica’s national parks (NPS), national wildlife refuges (NWRS), and biological reserves (BRS) was reaffirmed in another way: as a resource for nature tourism. Nature tourism is motivated by the desire to experience unspoiled nature: to see, enjoy, experience, or photograph scenery, natural communities, wildlife, and native plants. The first rule of nature tourism is that wildlife is worth more alive—in the wild—than dead. It has become a great incentive to protect wildlife from poachers and to conserve the forests as habitat for the wildlife.

Nature tourism provided new employment opportunities for Costa Ricans as travel agency personnel, outfitters, nature lodge owners and staff, drivers, and naturalist guides. The best naturalist guides can identify birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, flowers, butterflies, and trees. These dedicated guides share an infectious enthusiasm for the country as they help visitors experience hundreds of species during a visit. Guides like Carlos Gómez Nieto have seen more than 730 of the country’s bird species and can identify most of them by sight and sound.

Rainforests—especially the international loss of rainforests—received a great deal of publicity in the 1980s. Costa Rica’s national parks provided an opportunity to attract tourists to experience the mystique and beauty of those forests. Improved road systems and small airstrips throughout the country provided access to those parks and private reserves in the rainforests. Enterprising outfitters recognized the opportunity to establish locally owned and managed nature tourism lodges to cater to this new breed of international tourists.

One of the best-known pioneers in nature-based tourism is Michael Kaye. Originally from New York, he was a white-water rafting outfitter in the Grand Canyon before he founded Costa Rica Expeditions in 1985. In Costa Rica he provides tourists with the opportunity for adventure tourism, including white-water rafting and wildlife viewing. Kaye built three lodges—Tortuga, Monteverde, and Corcovado—and he provided ecologically based innovations and adaptations at these facilities that minimized their impact on the environment and sensitized visitors to the importance and vulnerability of the forests where these lodges were located. Kaye believes that tourists respond to world-class facilities and services that are provided by local ownership and management of smaller, dispersed lodging facilities. Costa Rica’s tourism forte is that it is one of the best rainforest destinations in the Americas because it is safe and easily accessible; the attraction is not the beaches where huge hotels are owned by corporations from other countries.

Birding guide Carlos Gómez Nieto.

There are now dozens of other locally owned nature-based lodges throughout the country. John Aspinall founded Costa Rica Sun Tours and built the Arenal Observatory Lodge. His brother Peter founded Tiskita Jungle Lodge. Don Perry initiated the Rainforest Aerial Tram facility. John and Kathleen Erb founded Rancho Naturalista and Tárcol Lodge. John and Karen Lewis founded Lapa Ríos. Other local nature lodges are Selva Verde, El Gavilán, Hacienda Solimar, La Pacifica, Caño Negro Lodge, La Ensenada, Villa Lapas, Rancho Casa Grande, Rara Avis, Savegre Mountain Lodge, Bosque de Paz, Drake Bay Wilderness Resort, and El Pizote Lodge. OTS research facilities like La Selva and San Vito also provide accommodations for nature tourists.

International connections also benefited Costa Rica’s nature tourism. In 1989, Preferred Adventures Ltd. was founded by Karen Johnson in St. Paul, Minnesota, with special emphasis on Costa Rican tourism. Through the efforts of Karen Johnson and the late Tony Andersen, Chairman of the Board and former CEO of the H. B. Fuller Company and Honorary Consul to Costa Rica from Minnesota, these connections resulted in the creation of the Costa Rica–Minnesota Foundation, which has promoted cultural, medical, and conservation projects in Costa Rica.

Ctenosaur sharing the beach with tourists, Tamarindo.

As nature tourism lodges proliferated after the mid-1980s, the number of tourists arriving in Costa Rica grew steadily. In 1988, about 330,000 tourists came, and over the next eleven years the number increased to 1,027,000 people per year. By 2006, the number of tourists had risen to 1,716,000. From 1988 to 2006, the annual number of national park visitors increased from about 865,600 to 1,205,100, and the number of tour operators increased from 58 to 325. All of this is happening in an area only one-fourth the size of Minnesota.

Nature tourism has turned heads throughout Costa Rica and Latin America because of the amount of income it has generated. In 1991, tourism contributed $330 million to the Costa Rican national economy. By 1999 that figure had increased to $940 million and exceeded the amount generated by exports of coffee ($408 million) and bananas ($566 million)! By 2006, tourism income exceeded one billion dollars: $1,620,800,000. In addition, nature tourism created more than 140,000 jobs.

The best thing about nature tourism is that when it is practiced ethically and in balance with the environment, it is a sustainable natural resource use that diversifies the economic base of the country and makes the value of the national parks and wildlife resources obvious to the citizenry.

Costa Ricans now realize that a significant part of the economic health and prosperity of their country is tied to the health and prosperity of their national parks, forests, and wildlife and to the future of the country’s macaws, quetzals, tepescuintles, Jaguars, and Green Turtles. Don Pepe Figueres was right. If you make the world a safe place for green turtles and other wildlife, it becomes a better place for people, too.

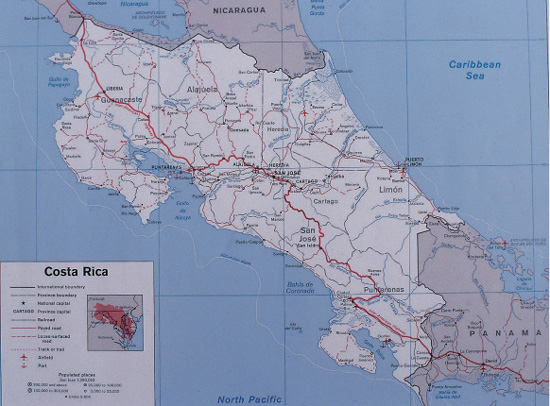

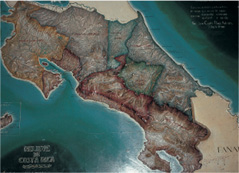

Costa Rica, a Central American country between Panama and Nicaragua, is shown in Figure 1. Considering its relatively small size, 19,653 square miles, Costa Rica has an exceptionally high diversity of plants and wildlife, more than half a million species. This is explained in part by the fascinating geological history of the region.

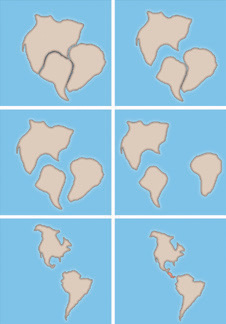

The geological history that led to the creation of Costa Rica goes back about 200 million years to the Triassic Period, when much of the earth’s landmass was composed of a supercontinent called Pangaea. The supercontinent began to separate through continental drift, portrayed in Figure 2, which is the process by which the earth’s landmasses essentially float on the molten core of the earth, drift among the oceans, and occasionally separate or merge. Pangaea eventually separated into two supercontinents. The northern supercontinent, called Laurasia, later became North America, Asia, and Europe. The southern portion, called Gondwanaland, drifted apart and later became South America, Africa, southern Asia, and Australia.

Figure 1. Location of Costa Rica in Central America.

About 130 million years ago the western portion of Gondwanaland began to separate into South America and Africa. Concurrently, the North American land-mass drifted westward from the European landmass. Both North America and South America drifted westward, but they were still separate. By the Pliocene Period, about three to four million years ago, North America and South America were aligned from north to south, but a gap in the ocean floor between the two continents existed where southern Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama are today.

Highway map of Costa Rica. Source: U.S. State Department.

About three million years ago an undersea plate of the earth’s crust, called a tectonic plate, began moving north and eastward in the Pacific Ocean into the area between North and South America. This particular tectonic plate, the Cocos Plate, pushed onto the Caribbean Plate and rose above sea level to create the land bridge that now connects North and South America. That bridge became southern Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and the central and western portions of Panama.

Figure 2. Stages in the process of continental drift that led to the creation of Costa Rica.

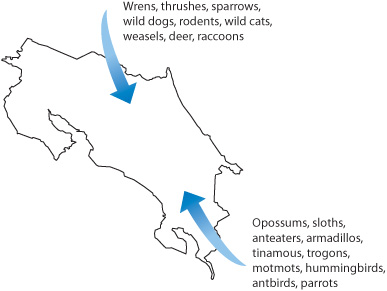

Biogeography is the relationship between the geography of a region and the long-term distribution and dispersal patterns of its plants and wildlife. The geological history of Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama created a situation in which they became a land bridge between two continents. Plants and wildlife have been dispersing across that bridge for the last three million years; as a result, Costa Rica became a biological mixing bowl of species from both continents. Those dispersal patterns are shown in Figure 3.

Temperate-climate plants that have dispersed southward from North America include alders (Alnus), oaks (Quercus), walnuts (Juglans), magnolias (Magnolia), blueberries (Vaccinium), Indian paint-brush (Castilleja), and mistletoe (Gaiadendron). Most dispersal appears to have occurred during cooler glacial periods. As the climate became warmer, these northern-origin plants became biologically stranded on the mountains, where the climate was cooler.

Wildlife dispersing from North America across the land bridge included coyotes, tapirs, deer, jaguars, squirrels, and bears. Birds that dispersed from North America to Central and South America included wrens, thrushes, sparrows, woodpeckers, and common dippers.

Topographical relief map of Costa Rica.

Plants that dispersed from South America toward the north included tree ferns, cycads, heliconias, bromeliads, orchids, poor-man’s umbrella (Gunnera), Puja, and Espeletia. Wildlife that dispersed northward from South America through Costa Rica are opossums, armadillos, porcupines, sloths, monkeys, anteaters, agoutis, and tepescuintles. Some species expanded through Central America and Mexico to the United States. Birds that dispersed from South America to Costa Rica and beyond include tinamous, hummingbirds, motmots, trogons, spinetails, flowerpiercers, antbirds, parrots, and woodcreepers. Likewise, insects have dispersed from both the north and south into Costa Rica.

Figure 3. Costa Rica became a land bridge that facilitated the dispersal of wildlife from both North and South America.

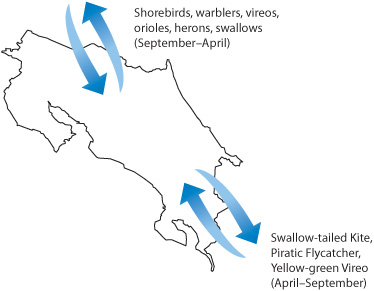

Figure 4. Patterns of bird migration from North and South America.

NORTHERN HEMISPHERE MIGRANTS

Among Costa Rica’s 882 bird species, about 180 are migratory. Most migrate from North America to winter in Latin America between September and April. Patterns of migration from the north and south are shown in Figure 4.

The story behind the migratory traditions and the origins of these migrants is both intriguing and surprising. Migratory birds are believed to have originated in the tropics. In tropical forests, insects are present in a great diversity of species, but the numbers of any one species are low. They can be very difficult for birds to find in adequate quantities to feed young. That is why the parents of many tropical bird species have young from previous broods that help feed their young. In northern temperate forests, the species diversity of insects is lower, but the seasonal abundance of each species can be great—as occurs in outbreaks of tent caterpillars. This is referred to as a “protein pulse” as it relates to bird food provided by insects. Such a bountiful supply of insects provides ideal conditions for parent birds to reproduce and adequately feed their young. The annual pattern of seasonal migration was likely tied to the passing of glacial periods, when mild northern summers and the increasing presence and abundance of northern insects benefited birds that migrated north to nest.

Among butterflies, the Monarch is famous for its international migrations between North America and Mexico, but it does not migrate to Costa Rica. The Monarchs there are nonmigratory. Some butterflies and moths in Costa Rica undergo irregular mass migrations that are mostly a one-way phenomenon. Perhaps the most conspicuous of these are the irregular cross-country migrations of an iridescent green page moth, Urania fulgens. Most of these movements occur within the country, but some species, like the Black Witch moth (Ascalapha odorata), can move northward into the United States.

SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE MIGRANTS

As most northern migrants are leaving for North America in March and April, a few birds are migrating from South America to Costa Rica to stay from April through September. The Swallow-tailed Kite, Piratic Flycatcher, Blue-and-white Swallow, and Yellow-green Vireo are migrants from South America.

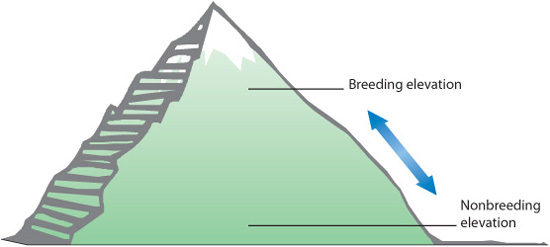

ELEVATIONAL MIGRANTS

Some resident birds, butterflies, and moths in Costa Rica, like the Three-wattled Bellbird, Mechanitis polymnia isthmia, Greta morgane oto, Marpesia merops, Marpesia coresia, and Marpesia chiron, migrate each year along an elevational gradient. For example, the Three-wattled Bellbird moves from breeding areas in middle-and high-elevation “temperate” forests during the rainy season (April through December) to lower-elevation “tropical” forests during the dry season (January through March), as illustrated in Figure 5. The Silver-throated Tanager, the Scarlet-thighed Dacnis, and many Costa Rican butterflies and moths carry out elevational migrations.

Figure 5. Some tropical insects and birds, like the Three-wattled Bellbird, carry out elevational migrations between breeding seasons and nonbreeding seasons.

An endemic species is one found in one country or region and nowhere else in the world. Costa Rica has three zones of endemism, in which unique species and subspecies are found. These zones occur because geographic barriers created by mountains, arid zones, or oceans have isolated a particular population from the rest of its species, and eventually they evolve into separate species through natural selection.

The mountain ranges and volcanoes of Costa Rica and western Panama include only about 160 species of birds out of the 882 species present in the country. The same holds true for insect species and subspecies; their diversity is reduced as the elevation increases. The concept of endemism is often applied to species in a single country, but in the case of the Costa Rican highlands, where the Talamanca Mountains are contiguous with those of western Panama, the area of endemism crosses the border. For example, Heliconius clysonymus montanus and Hypanartia dione arcaei are regional endemic species of the highlands in the Talamanca Mountains of Costa Rica and adjacent mountains of Panama. For the purposes of this book, it is considered a single endemic zone. Many butterflies have evolved into distinctive species or subspecies because they were reproductively isolated from other populations of the same species or similar species in the mountains of Guatemala and southern Mexico and in the mountains of eastern Panama and Colombia. This highland endemic zone is portrayed in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Highland zone of endemic species in Costa Rica and western Panama.

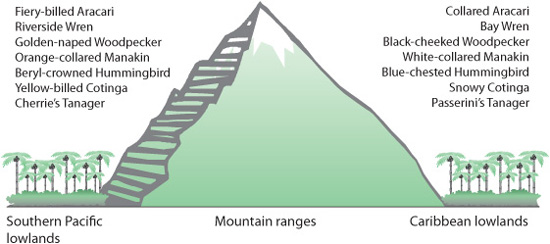

Costa Rica’s mountain ranges serve as a giant barrier that separates moist and wet lowland rainforest species that originally dispersed from South America to both the Caribbean lowlands and the southern Pacific lowlands. The mountains have caused reproductive isolation between populations of species that occurred in both areas. Over geologic time, the species diverged into separate species. This has contributed to a second zone of endemism in Costa Rica, the southern Pacific lowlands. There are several interesting pairs of species that have a common ancestor but have been separated from each other by the mountains between the Caribbean lowlands and the southern Pacific lowlands, as shown in Figure 7. Since the range of one species does not overlap the range of the other species in the pair, these are referred to as allopatric species.

Figure 7. Closely related pairs of allopatric species of the Caribbean and Pacific lowlands that share a common ancestor but are now separated by Costa Rica’s mountains.

This divergence of two species from a common ancestor is a continuing process, as evidenced by the recent decision by taxonomists to split the Scarlet-rumped Tanager into two species, Cherrie’s Tanager in the Pacific lowlands and Passerini’s Tanager in the Caribbean lowlands. The males are identical, but the females are distinctive. Other birds designated as endemic subspecies include the Masked Yellowthroat (Chiriquí race) and the Variable Seedeater (Pacific race). One day they may eventually become different enough from the Caribbean subspecies to be designated as new species.

Additional endemic species of the southern Pacific lowlands that do not have a corresponding closely related species in the Caribbean lowlands include Baird’s Trogon, Black-cheeked Ant-Tanager, Granular Poison Dart Frog, Mangrove Hummingbird, Heliconius ismenius clarescens, and Red-backed Squirrel Monkey.

A third zone of endemism is Cocos Island. This island is 600 miles out in the Pacific, and three endemic birds have evolved there: Cocos Finch, Cocos Cuckoo, and Cocos Flycatcher. Cocos Island is an extension of the Galápagos Island archipelago but it is owned by Costa Rica. There are thirteen finches on the Galápagos Islands commonly referred to as Darwin’s finches. The Cocos Finch is actually the fourteenth Darwin’s finch. Undoubtedly, a variety of invertebrates are endemic to this island also.

The previous discussion of endemic species applies best to birds. The dynamic and changing taxonomic status of many butterflies, moths, and other insects, however, is a fascinating phenomenon that goes beyond traditional geographic barriers as a driving force behind natural selection and the creation of new species. The evolution of new species from a common ancestor can occur as a species diverges to utilize different host plant species across the range of the common ancestor. The pioneering work by Dr. Dan Janzen and the gusaneros (parataxonomists) of the Guanacaste Conservation Area has contributed to the development of a research tool called DNA barcoding.

Dan Janzen with parataxonomist Osvaldo Espinoza of the Guanacaste Conservation area.

Astraptes fulgerator.

The analysis of mitochondrial DNA from moths and butterflies in the Guanacaste Conservation Area has revealed that some insects that were formerly considered a single species actually belong to a closely related group of separate but similar-looking species that depend on different host plants. For example, a colorful and conspicuous skipper butterfly formerly called Astraptes fulgerator is found from Texas to Argentina. DNA barcoding analysis of host plant use has revealed that this butterfly is now ten different species that all look very similar. Many of these new species could potentially be considered as endemic, but that title is not relevant at this point because more research is needed; the new species have not yet been assigned scientific names, and they have no common names.

The most detailed and traditional classification of the habitats in Costa Rica includes twelve “life zones,” as described by the late Dr. Leslie Holdridge of the Tropical Science Center. Those life zones are based on average annual precipitation, average annual temperature, and evapotranspiration potential. Evapotranspiration potential involves the relative amount of humidity or aridity of a region.

For tourism planning purposes, that classification system has been simplified in this book from twelve to six biological zones. These zones, the first five of which are shown in Figure 8, coincide with the distribution of many Costa Rican wildlife species and are designed for trip planning by wildlife tourists. The sixth zone consists of the entire coastline of both the Pacific and the Caribbean coasts. A good trip itinerary should include at least three biological zones in addition to the Central Plateau.

Figure 8. Five biological zones of Costa Rica. In addition, the country’s entire coastline, beaches, and mangrove lagoons make up a sixth zone of biological importance.

Tropical dry forest in Guanacaste.

The tropical dry forest in northwestern Costa Rica is a lowland region that generally coincides with the boundaries of Guanacaste Province. It extends eastward to the Cordilleras of Guanacaste and Tilarán, southeast to Carara NP, and north to the Nicaragua border. This zone extends from sea level to approximately 2,000 feet in elevation.

This region is characterized by a pronounced dry season from December through March. The deciduous trees include many plants that lose their leaves during the dry season and flower during that leafless period. Common trees are bullhorn acacia (Acacia), Tabebuia, strangler fig (Ficus), Guazuma, kapok (Ceiba), Bombacopsis, buttercup tree (Cochlospermum), Anacardium, and the national tree of Costa Rica, the Guanacaste tree (Enterolobium cyclocarpum). The tallest trees approach 100 feet in height. Rainfall ranges from 40 to 80 inches per year.

Epiphytes are not a major component of the dry forest canopy, as they are in the moist and wet forests. However, some trees are thickly covered with vines like monkey vine (Bauhinia) and Combretum. The ease with which this forest can be burned and cleared for agricultural purposes has made the tropical dry forest the most endangered habitat in the country.

An important habitat within the dry forest consists of the riparian forests along the rivers, also called gallery forests. They maintain more persistent foliage during the dry season.

Wetlands, estuaries, islands, and backwaters of this region’s rivers are also a major habitat for wetland wildlife. Especially important are lands along the Río Tempisque, its tributaries, and the wetlands of Palo Verde NP. Important examples of tropical dry forest habitat are preserved in Guanacaste Province; Santa Rosa, Las Baulas, and Palo Verde NPs; and Lomas Barbudal BR. The southeastern limit of this region is at Carara NP, which has a combination of wildlife characteristic of both the dry forest and the southern Pacific lowlands.

Southern Pacific lowland forest, Manuel Antonio National Park.

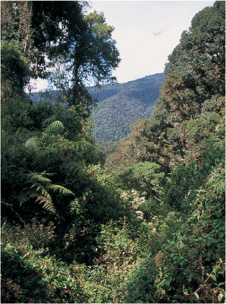

The southern Pacific lowlands include the moist and wet forested region from Carara NP through the General Valley, Osa Peninsula, and Golfo Dulce lowlands to the Panama border and inland to the premontane forest zone at San Vito las Cruces.

The moist and wet forests of this region receive 80 to 200 inches of rainfall per year, with a more pronounced dry season from December through March than occurs in the Caribbean lowlands. These forests have fewer epiphytes than are found in Caribbean lowland forests. The tallest trees exceed 150 feet in height.

Among tree species are the kapok (Ceiba), Anacardium, strangler fig (Ficus), wild almond (Terminalia), purpleheart (Peltogyne purpurea), Carapa, buttercup tree (Cochlospermum vitifolium), Virola, balsa (Ochroma), milk tree (Brosimum), Raphia, garlic tree (Caryocar costaricense), and Hura. Understory plants include species like bullhorn acacia (Acacia), walking palm (Socratea), Bactris, and Heliconia. Most trees maintain their foliage throughout the year.

Central Plateau overlooking San José and suburbs.

Much of this region has been converted to pastureland and plantations of pineapple, coconut, and African oil palm. Among the most significant reserves remaining in natural habitat are Carara, Manuel Antonio, and Corcovado NPs. Corcovado NP is one of the finest examples of lowland wet forest in Central America, and it has excellent populations of rainforest wildlife. Additional private reserves include one near San Isidro del General at Los Cusingos, the former home of Dr. Alexander and Pamela Skutch. It is now managed by the Tropical Science Center. The Wilson Botanical Garden at San Vito is an excellent example of premontane wet forest and is owned and operated by the Organization for Tropical Studies. The southern Pacific lowland area is of biological interest because it is the northernmost range limit for some South American species.

Premontane (middle-elevation) sites like the Wilson Botanical Garden at San Vito are included in this biological region because many of the species typical of this region are found up to about 4,000 feet along the western slopes of the Talamanca Mountains. Premontane forests, like those preserved at the Wilson Botanical Garden, are the second most endangered life zone in Costa Rica, after tropical dry forests.

The Central Plateau contains the human population center of Costa Rica. The capital, San José, and adjoining suburbs are located in this relatively flat plateau at an elevation of approximately 3,900 feet. It is bordered on the north and east by major volcanoes of the Central Cordillera: Barva, Irazú, Poás, and Turrialba. To the south is the northern end of the Talamanca Mountains.

Rainfall ranges from 40 to 80 inches per year, and the original life zone in this area was premontane moist forest, but that forest has been largely cleared. The climate of the region, about 68 degrees Fahrenheit year-round, made it ideal for human settlement, and the rich volcanic soils made it an excellent region for growing coffee and sugarcane. The region is also important for production of fruits, vegetables, and horticultural export products like ferns and flowers.

Although premontane moist forests of the Central Plateau are largely gone, extensive plantings of shrubs, flowers, and fruiting and flowering trees throughout the San José area have made it ideal for adaptable wildlife species. Shade coffee plantations are preferred habitats for songbirds, including Neotropical migrants. Living fence posts of Erythrina and Tabebuia are excellent sources of nectar for birds and butterflies. Private gardens abound with butterflies and Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds. Remaining natural places, like the grounds of the Parque Bolívar Zoo in San José, host many wild, free-living butterflies and songbirds.

The Caribbean lowlands include moist and wet lowland forests from the Caribbean coast westward to the foothills of Costa Rica’s mountains. The Caribbean lowland fauna extends from the Río Frio and Los Chiles area southeastward to Cahuita and the Panama border. For the purposes of this book, the region extends from sea level to the upper limit of the tropical zone at about 2,000 feet elevation. The premontane forest, at least up to about 3,200 feet, also contains many lowland species. This region receives 80 to 200 inches of rainfall annually.

The trees grow to a height of over 150 feet. This is an evergreen forest that receives precipitation throughout the year and does not have a pronounced dry season like the moist and wet forests of the southern Pacific lowlands. Trees include coconut palms (Cocos), raffia palms (Raphia), Carapa, Pentaclethra, kapok (Ceiba), swamp almond (Dipteryx panamensis), Alchornea, walking palm (Socratea), and Pterocarpus. Tree branches have many epiphytes, such as bromeliads, philodendrons, and orchids. The complexity of the forest canopy contributes to a high diversity of plant and animal species in the treetops. Plants of the understory and forest edge include passionflower (Passiflora), Hamelia, Heliconia, palms, Costus, and Canna.

Caribbean lowland wet forest, Tortuguero National Park.

Much of this region has been cleared and settled for production of cattle and bananas. Remaining forest reserves include Tortuguero and Cahuita NPs, Gandoca-Manzanillo NWR, Hitoy-Cerere BR, lower elevations of La Amistad and Braulio Carrillo NPs, and Caño Negro NWR. Tortuguero NP is one of the most extensive reserves and one of the best remaining examples of rainforest in Central America. Canals at Tortuguero and open water of the Río Frío and at Caño Negro provide excellent opportunities for viewing wildlife from boats. The grounds of Rara Avis also provide an excellent protected reserve at the upper elevational limit of this biological zone. La Selva Biological Field Station, owned and managed by the OTS, has an exceptional boardwalk and trail system that allows easy viewing of rainforests and rainforest wildlife.

Lower levels of Braulio Carrillo NP offer excellent examples of moist and wet lowland forest.

The Caribbean lowlands are significant as an excellent example of tropical habitat that supports classic rainforest species in all their complex diversity, beauty, and abundance.

The highland biological zone comprises Costa Rica’s four mountain ranges. This zone includes lower montane, montane, and subalpine elevations generally above 4,200 to 4,500 feet in elevation.

Five volcanoes near the Nicaragua border form the Cordillera of Guanacaste: Orosí, Rincón de la Vieja, Santa María, Miravalles, and Tenorio.

The second group of mountains is the Cordillera of Tilarán. It includes the still-active Arenal volcano, which exploded in 1968, and mountains that are part of the Monteverde Cloud Forest.

Third is the Central Cordillera, which includes three large volcanoes that encircle the Central Plateau—Poás, Irazú, and Barva—and Volcano Turrialba southeast of Barva. Poás is active, and Irazú last erupted in 1963. Turrialba was becoming restless in 2008.

The fourth highland region is composed of the great chain of mountains from Cartago to the Panama border. They are the Talamanca Mountains and Cerro de la Muerte, which are of tectonic origin rather than volcanic. Included is Cerro Chirripó, the highest point in Costa Rica at 15,526 feet. These mountains were formed when the Cocos Tectonic Plate pushed up from beneath the ocean onto the Caribbean Tectonic Plate about three to four million years ago. Much of this mountain range is protected as Tapantí NP (11,650 acres), Chirripó NP (123,921 acres), and La Amistad Costa Rica–Panama International Park (479,199 acres).

Crater of Poás volcano.

Talamanca Mountains, Cerro de la Muerte.

Figure 9. Humboldt’s Law: Each 300 feet of ascent on a tropical mountain is comparable to traveling sixty-seven miles north in latitude in terms of changes in average annual temperature.

SPECIES DIVERSITY

Species diversity decreases with increasing elevation. Out of Costa Rica’s 882 species of birds, about 130 species can be expected above 6,000 feet. About 105 species can be expected above 7,000 feet, about 85 can be found above 8,000 feet, and about 70 bird species can be expected above 9,000 feet. Comparable trends of lower diversity at higher elevations could also be expected among Costa Rica’s invertebrate populations.

HUMBOLDT’S LAW

The South American explorer Alexander von Humboldt recognized an interesting relationship in tropical countries with high mountains. As one travels up a mountain, the average annual temperature decreases by 1 degree Fahrenheit for each increase of 300 feet in elevation. As one travels northward from the equator, the mean annual temperature decreases by 1 degree Fahrenheit for each sixty-seven miles of change in latitude. So an increase of 300 feet elevation on a mountain in the tropics is broadly comparable to traveling sixty-seven miles north. This relationship is portrayed in Figure 9 and is referred to as Humboldt’s Law.

Some interesting changes in plant and animal life become apparent in travel up a mountain in the tropics that biologically resemble northward travel in latitude. The relationship of latitude and elevation becomes apparent at higher elevations because there are many temperate-origin plants and birds in the highlands. For example, the avifauna present at 8,000 feet on Costa Rica’s mountains includes a higher proportion of temperate-origin thrushes, finches, juncos, and sparrows than is found in the tropical lowlands. It is interesting that the Painted Lady butterfly (Vanessa virginiensis) is found in temperate regions of North America and also at the highest elevations in the paramo of Costa Rica.

Figure 10. Costa Rica’s five elevational zones.

Many plants of higher elevations in Costa Rica are in the same genera as plants found in the northern United States and Canada, including alders (Alnus), oaks (Quercus), blueberries (Vaccinium), blackberries (Rubus), bayberries (Myrica), dogwoods (Cornus), bearberry (Arctostaphylos), Indian paintbrush (Castilleja), and boneset (Eupatorium). Of course, in temperate areas there is a great deal more variation above and below the annual average temperature than in tropical areas, where there is little variation throughout the year; and in Costa Rica, there has never been a snowfall.

ELEVATIONAL ZONES

To understand the role that elevation plays in plant and animal distribution, it is useful to understand the main categories by which biologists classify elevations and how those zones relate to the highlands. These elevational zones are shown in Figure 10 and described below.

TROPICAL LOWLANDS: The tropical lowland zone ranges from sea level to about 2,300 feet on the Pacific slope and 2,000 feet on the Caribbean slope. The lowland zone includes dry forests like those in Guanacaste as well as moist and wet forests of the southern Pacific and Caribbean lowlands.

PREMONTANE ZONE: This zone is called the “foothills” or “subtropical” zone and is also referred to as the “middle-elevation” zone. Some birds and other animals are found only in the foothills. Examples are Speckled and Silver-throated Tanagers. This zone ranges from about 2,300 feet to 4,900 feet on the Pacific slope and 2,000 feet to 4,600 feet on the Caribbean slope. It could also be called the coffee zone because it is the zone in which the conditions are ideal for coffee production—and for human settlement.

LOWER MONTANE ZONE: The lower montane zone is part of the highlands. It includes the region from 4,900 feet to 8,500 feet on the Pacific slope and 4,600 feet to 8,200 feet on the Caribbean slope. One special habitat that occurs within this zone, and in upper levels of the premontane zone, is cloud forest. The cloud forest occurs roughly from 4,500 to 5,500 feet. A cloud forest, like that at Monteverde, is characterized by fog, mist, and high humidity as well as high precipitation—about 120 to 160 inches per year. The emerging problem of climate change is now causing the Monteverde forests to become drier and is placing cloud forest species of plants and wildlife in serious jeopardy.

Orchids, bromeliads, philodendrons, and dozens of other epiphytes grow in lush profusion among the branches of cloud forest trees.

MONTANE ZONE: The montane zone ranges from 8,500 feet to 10,800 feet on the Pacific slope and from 8,200 feet to 10,500 feet on the Caribbean slope. Among plants of lower montane and montane zones are many of northern temperate origins: oak (Quercus), blueberry (Vaccinium), bearberry (Arctostaphylos), bamboo (Chusquea), alder (Alnus), bayberry (Myrica), magnolia (Magnolia), butterfly bush (Buddleja), elm (Ulmus), mistletoe (Gaiadendron), boneset (Eupatorium), dogwood (Cornus), Indian paintbrush (Castilleja), and members of the blueberry family (Ericaceae) like Satyria, Cavendishia, and Psammisia. Other conspicuous plants are Oreopanax, Senecio, Miconia, Clusia, Bomarea, giant thistle (Cirsium), Monochaetum, wild avocado (Persea), poor-man’s umbrella (Gunnera), and tree ferns.

Montane wet forest, Cerro de la Muerte.

SUBALPINE PARAMO: Above the montane zone is the area above the treeline called the paramo. It has short, stunted, shrubby vegetation, including bamboo (Chusquea), many composites (like Senecio), and plants of South American origin from the Andes: a terrestrial bromeliad called Puya dasylirioides and a yellow-flowered composite with fuzzy white leaves called lamb’s ears (Espeletia).

Subalpine rainforest paramo.

Cloud forest vegetation, Monteverde.

The sixth biological zone, not portrayed on the map of biological regions (Fig. 8), includes all Pacific and Caribbean coastlines that extend from Nicaragua to Panama. This shoreline habitat consists of the beaches to the high-tide line and adjacent forests, offshore islands, rocky tidepools exposed at low tide, coral reefs, and mangrove lagoons. Among the more notable islands are Caño Island and Cocos Island. The only coral reef is at Cahuita NP.

Coastal beaches and river estuaries are extremely important as habitat for migratory shorebirds, seabirds, sea turtles, and mangrove-dependent wildlife species. Costa Rica’s beaches are extremely important as nesting sites for Green Turtles on the Caribbean coast and for Ridley Turtles, Hawksbill Turtles, and Leatherback Turtles on the Pacific coast.

Other important coastal habitats that are critically endangered by foreign beachfront developers and pollution are those of the mangrove lagoons and mangrove forests. These are important nurseries for fish and wildlife. Significant mangrove lagoons exist at Tamarindo, Playas del Coco, Gulf of Nicoya, Parrita, Golfito, Chomes, Boca Barranca, Quepos, and the 54,362-acre Mangrove Forest Reserve of the Ríos Térraba and Sierpe. They provide exceptional wildlife-watching opportunities during guided boat tours.

The fauna of Costa Rica includes thousands of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, butterflies, moths, and other invertebrates. This diversity can be both overwhelming and inspiring to a nature enthusiast. Even the casual tourist is drawn to the tropical beauty and appeal of monkeys, motmots, and morphos.

Río Tárcoles estuary.

This book has been written to help visitors to Costa Rica know more about the identity and ecology of both common and unusual butterflies, moths, and other invertebrates that they may encounter. There are field guides just for birds, reptiles, mammals, or butterflies, but most tourists are interested in all kinds of wildlife. The first edition of the Field Guide to the Wildlife of Costa Rica, published in 2002, proved to be very popular. This newly revised approach has split the previous book’s wildlife coverage into three volumes. The first covers the country’s diverse birdlife, including more than three hundred species accounts. It will leave you overwhelmed by the beauty, diversity, and fascinating ecological adaptations of birds in Costa Rica.

This volume is the second in the series, including more than 100 of the more common and conspicuous butterflies, moths, and other selected invertebrates. Even with that many accounts, this is still just a sampler of the wonderful diversity of Costa Rica’s invertebrates. The invertebrates chosen are among the most interesting to tourists, based on my experience in leading tours to Costa Rica since 1987. Some of these are the larger, more colorful species, like morpho butterflies, saturnid moths, huge beetles, and well-known rainforest insects like army ants.

More than 160 photos, mostly by the author, illustrate the accounts. These photos represent the best photos available from a personal collection of more than 60,000 Costa Rican and Latin American nature and wildlife images. Additional photos have been provided by Dr. Daniel H. Janzen for the Oxytenis modestia caterpillar and Fulgora laternaria. The postures, behavior, and natural colors displayed by these photos of the creatures alive and in the wild provide the best reference for nature enthusiasts. Paintings usually fail to capture the correct colors, stunning iridescence, and resting postures of many tropical butterflies and other insects, because they are often painted from dead or faded museum specimens.

Mangrove lagoon at Quepos.

Most of the author’s butterfly photos were taken with a Pentax PZ-1 equipped with a Tamron 90 mm macro lens and a 1.7× Pentax teleconverter and a Pentax AF240FT flash. Fuji 100 Sensia I and Sensia II film was used for the slides. Photos taken after 2005 were taken with a Canon 20D digital camera.

Over 80 percent of the wildlife images included in this book were photographed in the wild, primarily in Costa Rica. Some have been photographed in the wild in other countries of Latin America. The remaining images were taken in captive settings either in Latin America or the United States. In only a few cases were photos of dead specimens used to highlight identification details, like the paired eyespots on the underside of a Caligo butterfly’s wings. Some photos have been enhanced through the use of Adobe Photoshop to highlight identification marks and remove distracting background features.

Acuña, Vilma Obando. 2002. Biodiversidad en Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial INBIO. 81 pp.

Beletsky, Les. 1998. Costa Rica: The Ecotravellers’ Wildlife Guide. San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press. 426 pp.

Boza, Mario A. 1987. Costa Rica National Parks. San José, Costa Rica: Fundación Neotrópica. 112 pp.

———. 1988. Costa Rica National Parks. San José, Costa Rica: Fundación Neotrópica. 272 pp.

Cahn, Robert. 1984. An Interview with Alvaro Ugalde. The Nature Conservancy News 34(1): 8–15.

Carr, Archie, and David Carr. 1983. A Tiny Country Does Things Right. International Wildlife 13(5): 18–25.

Chalker, Mary W. 2007. Exploring Costa Rica 2008/9. San José, Costa Rica: Tico Times. 464 pp.

Cornelius, Stephen E. 1986. The Sea Turtles of Santa Rosa National Park. San José, Costa Rica: Fundación de Parques Nacionales. 64 pp.

Ehrenfeld, David. 1989. Places. Orion Nature Quarterly 8(3): 5–7.

Franke, Joseph. 1997. Costa Rica’s National Parks and Preserves: A Visitor’s Guide. Seattle: The Mountaineers. 223 pp.

Gómez, Luis Diego, and Jay M. Savage. 1983. Searchers on That Rich Coast: Costa Rican Field Biology, 1400–1980. In Costa Rican Natural History, ed. Daniel H. Janzen, 1–11. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. 816 pp.

Henderson, Carrol L. 1969. Fish and Wildlife Resources of Costa Rica, with Notes on Human Influences. Master’s thesis, Univ. of Georgia, Athens. 340 pp.

Holdridge, Leslie R. 1967. Life Zone Ecology. San José, Costa Rica: Tropical Science Center. 206 pp.

inicem. 1998. Costa Rica: Datos e Indicadores Básicos. Costa Rica at a Glance. Miami: inicem Group. Booklet. 42 pp.

Janzen, Daniel H. 1990. Costa Rica’s New National System of Conserved Wildlands. Mimeographed report. 15 pp.

———. 1991. How to Save Tropical Biodiversity: The National Biodiversity Institute of Costa Rica. American Entomologist 36(3): 159–171.

Kohl, Jon. 1993. No Reserve Is an Island. Wildlife Conservation 96(5): 74–75.

Lewin, Roger. 1988. Costa Rican Biodiversity. Science 242: 1637.

Lewis, Thomas A. 1989. Daniel Janzen’s Dry Idea. International Wildlife 19(1): 30–36.

Market Data. 1993. Costa Rica: Datos e Indicadores Básicos. Costa Rica at a Glance. San José, Costa Rica. 36 pp.

McPhaul, John. 1988. Peace, Nature: C. R. Aims. Tico Times 32(950): 1, 21.

Meza Ocampo, Tobías A. 1988. Areas Silvestres de Costa Rica. San Pedro, Costa Rica: Alma Mater. 112 pp.

Murillo, Katiana. 1999. Ten Years Committed to Biodiversity. Friends in Costa Rica 3: 23–25.

Pariser, Harry S. 1998. Adventure Guide to Costa Rica. 3rd ed. Edison, N.J.: Hunter. 546 pp.

Pistorius, Robin, and Jeroen van Wijk. 1993. Biodiversity Prospecting: Commercializing Genetic Resources for Export. Biotechnology and Development Monitor 15: 12–15.

Pratt, Christine. 1999. Tourism Pioneer Wins Award, Hosts Concorde. Tico Times 43(1507): 4.

Rich, Pat V., and T. H. Rich. 1983. The Central American Dispersal Route: Biotic History and Paleogeography. In Costa Rican Natural History, ed. Daniel H. Janzen, 12–34. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press. 816 pp.

Sandlund, Odd Terje. 1991. Costa Rica’s inbio: Towards Sustainable Use of Natural Biodiversity. Norsk Institutt for Naturforskning. Notat 007. Trondheim, Norway. Report. 25 pp.

Sekerak, Aaron D. 1996. A Travel and Site Guide to Birds of Costa Rica. Edmonton, Alberta: Lone Pine. 256 pp.

Skutch, Alexander F. 1971. A Naturalist in Costa Rica. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. 378 pp.

———. 1984. Your Birds in Costa Rica. Santa Monica, Calif.: Ibis. Brochure. 8 pp.

Sun, Marjorie. 1988. Costa Rica’s Campaign for Conservation. Science 239: 1366–1369.

Tangley, Laura. 1990. Cataloging Costa Rica’s Diversity. BioScience 40(9): 633–636.

Ugalde, Alvaro F., and María Luisa Alfaro. 1992. Financiamiento de la Conservación en los Parques Nacionales y Reservas Biológicas de Costa Rica. Speech presented at the IV Congreso Mundial de Parques Nacionales, Caracas, Venezuela, February. Mimeographed copy. 16 pp.

Zúñiga Vega, Alejandra. 1991. Archivo de riqueza natural. La Nación, Section B, Viva, February 4.

———. 1991. Estudios de los manglares. La Nación, Section B, Viva, February 4.