Except for its nearly disastrous consequences, the sequel to the Lisbon and Cassibile amateur theatricals took on aspects of an opéra bouffe. Altogether too much wishful thinking egged on all the chief players. Smith went all out for Giant II because without the promised airborne operation, the Italians would not play ball. As Murphy reported to the president, “all thought the risk was worth taking even if [the Eighty-second Airborne was] lost.”1 All, that is, save the two officers most responsible for Giant II: Ridgway and Taylor. When Ridgway cautioned that the Italians were “deceiving us and have not the capability for doing what they are promising,” Smith painted a picture of popular resistance in Rome paralyzing the German defense.2 Smith never professed much faith in psychological warfare, but he convinced himself that Allied propaganda and the aerial campaign had swayed Italian attitudes. Guilty of mirror imaging, the Allies grossly inflated the potential impact of public opinion on Badoglio’s thinking. Allied broadcasts certainly encouraged Italians’ belief that the end of the war lay in sight and raised expectations for their deliverance, but they also rendered the Italian population even more inert. Italians wanted an end to hostilities, not a war of liberation. Twenty years of fascism had gutted Italian civil society; there was never any prospect of a national rising en masse. Nor was there an Italian de Gaulle to inspire resistance.

Allied airborne operations to date hardly inspired confidence. Ridgway also questioned Allied capabilities in staging Giant II. The Torch landings had amounted to a total wash, and the drops in Sicily brushed with disaster. Still, the airborne forces remained AFHQ’s favorite toy. For better than a month, Ridgway’s staff prepared for one dubious operation after another, including an amphibious landing in Naples, even though “not one individual in the entire division, officer or enlisted man, had ever had any experience or instruction in amphibious operations.”3 None proved more ill-advised than Giant II. Because of the shortage of lift—a product of the huge losses sustained from friendly fire in Husky—two-thirds of the division would land piecemeal in three stages over two days and nights more than 200 miles from the beaches of Salerno. Professing “full faith” in Italian assurances, Alexander promised Allied forces would make contact with Ridgway’s division “in three days—five days at the most.” When Ridgway protested the “sacrifice of my division,” Alexander sanctioned the dispatch of a mission to Rome for an assessment of Italian preparations.4

Smith and Alexander based the plan on two assumptions: the Italian forces could control territory and oppose the Germans, and Giant II and Italian resistance would compel Kesselring’s withdrawal into northern Italy. In Rome, that meant Italian forces directly attacking German formations and Kesselring’s headquarters, interrupting communications, and providing logistical support. Outside of Rome, the preoccupation remained fixed on securing the Italian navy. The Italians needed to secure the ports of La Spezia, Taranto, and Brindisi. By 7 September, the day the secret mission arrived in Rome, Alexander’s faith in Italian promises had faded. After four days of intensive planning with Castellano in Cassibile, and “despite our detailed instructions,” Alexander concluded that the Italians “have done nothing.”5 Still, he never intervened and canceled Giant II, presumably because that decision remained a “family affair.”

Alexander’s anxieties proved accurate. On 3 September Badoglio opened a meeting of his chiefs of staff by announcing, “His Majesty has decided to begin negotiations for an armistice.” Only his closest confidants knew he had already authorized the surrender. Badoglio issued no written orders instructing the movement of troops, despite his commitment to defend Rome. The Italian leadership knew Allied plans. As ADM Raffaele de Courten, head of the navy staff, recorded during the meeting: “The British and Americans will mount small-scale landings in Calabria, then a large-scale landing near Naples (six divisions), and finally a paratroop landing of a division near Rome, where Carboni’s six divisions and the Italian 4th Army will be concentrated.”6 Reference to the Fourth Army indicates that the Italians presumed a delay in the armistice’s announcement until much later. Much of the Fourth Army remained spread out from Liguria through Piedmont and back into France. Neither Badoglio nor Ambrosio forwarded instructions expediting the movement of Italian reinforcements toward Rome, doubtless owing to fear of alerting the Germans. From the outset, Badoglio ignored commitments made to the Allies through Castellano, deferring any action until after the announcement of the armistice.

On 4 September Smith began organizing an Italian military mission to AFHQ and asked Castellano to solicit approval from Rome. He also wanted permission for Taylor’s special mission. According to Castellano, Smith took him aside and said, “I understand very well the great anxiety which you have to know these dates, but unfortunately I can tell you nothing; it is a military secret.” Then in a whisper, Smith told him, “I can say only that the landing will take place within two weeks.” By reaffirming the two-week window, Smith wished to convey the immediacy of the Allied invasion, but Castellano stated in his letter to Ambrosio that although Smith refused to pin down the date, “the landing will … take place between the 10th and 15th of September, possibly the 12th.”7 MAJ Luigi Marchesi, who accompanied Castellano to Cassible, returned to Rome on 5 September with the plans for Giant II and the letter for Ambrosio. Castellano promised Italian forces would keep open the Furbana and Cerveteri air bases for the initial landings and secure the port at Ostia and approaches on either side of the Tiber for the landing of antitank ordnance.

Roatta did not receive the operational orders for the airborne landings until 6 September. It suddenly dawned on him that Italian troops would be making the first move against the Germans. Axis intelligence detected the movement of Allied landing craft, signaling the imminence of the amphibious operation in the Salerno-Naples area. Ambrosio dismissed Roatta’s concerns based on Castellano’s estimate, believing that nothing would happen until 12 September at the earliest. Carboni, commander of the motorized corps and now head of Italian Military Intelligence, rejected any notion of initiating actions against the Germans.8 The Air Ministry claimed it needed seven days to make the necessary arrangements for securing the two air bases. All this appears even more amazing in light of cables from Algiers warning the Italian regime “of absolute imminence of operation and date already fixed” and advising it to “maintain continuous watch every day for the most important message” and expect a communication “on or after 7 September.”9 Despite all evidence to the contrary, the Italian leadership convinced themselves they still had some latitude. Led by Roatta, they called for a reexamination of the airborne drop and the timing of the armistice announcement in light of extant circumstances. Roatta wrote a note to this effect and dispatched it with MAJ Alberto Briatore, one of the officers tabbed to join the military mission in Algiers. The memo reneged on the armistice and accused the Allies of bad faith for landing too soon, too far from Rome, and in insufficient force. “It is necessary,” it argued, “not to initiate hostilities [against the Germans]. Therefore the intervention of the airborne division should not take place.”10

While all this transpired in Rome, Taylor, accompanied by COL William Gardiner, started out from Palermo first in a British PT boat, then an Italian corvette, and finally a Red Cross ambulance. They arrived in Rome at dusk on 7 September. Their mission involved finalizing arrangements for joint action with Italian ground units, but in reality it centered on ascertaining whether Castellano’s assurances possessed any substance.11 The only preparations the Italian leadership made were for a lavish dinner held at the Palazzo Caprara, across from the War Ministry. Ambrosio had conveniently absconded to Turin the previous day, leaving Carboni the unpleasant task of dealing with Taylor. The Italian general finally showed up at 9:30. Taylor requested to inspect the airfields and informed Carboni the operation was set for the following day. Unmoved, the Italian general flippantly opined that the operation should be canceled. He exaggerated the strength of German armor by a factor of ten and diminished the number of Italian troops by half. Carboni lied, telling Taylor the Italian forces possessed virtually no fuel reserves, rendering his so-called motorized corps immobile.12

Taylor could scarcely credit what he had heard and demanded an audience with Badoglio. When he arrived at the marshal’s sumptuous palace, Taylor learned Badoglio was asleep. When he was finally awoken, Badoglio, in his pajamas, confirmed everything Carboni had told Taylor.13 To Taylor’s astonishment, the old marshal professed surprise “at the rapid course of events” and then repudiated all the agreements Castellano had made in his name. Given the utter unpreparedness of the Italian forces, Badoglio recommended the cancelation of Giant II and the postponement of the armistice announcement. Now incredulous, Taylor pleaded with Badoglio to reconsider his requests. From the marshal’s silence, Taylor inferred he already had. Taylor then asked that Badoglio forward a dispatch to Algiers. He complied, stating, “Operation Giant Two is no longer possible because of lack of forces to guarantee the airfields.” Taylor wrote a second wire stating, “GIANT Two is impossible.” The next morning, Taylor forwarded a third and finally a fourth cable, the last one containing the code words “Situation Innocuous,” signaling the cancellation of the operation.14 On the afternoon of 8 September, AFHQ ordered Taylor and Gardiner’s immediate return to La Marsa; they brought along GEN Francesco Rossi, the Italians’ deputy chief of staff, to argue for a postponement of Eisenhower’s announcement of the armistice.

AFHQ and Fifteenth Army Group never understood the Italians. A master of manipulation, Mussolini had built his regime on an admixture of concoction, co-option, and coercion. He promoted to senior positions only those fascist loyalists who reinforced Il Duce’s fanciful worldview—men skilled in veiling their own incompetence and sleaze. With the departure of the puppeteer, it was unrealistic to expect the marionettes to suddenly generate spines. The Allied propaganda blitz had scored successes, chiefly with Badoglio and his ministers, the army commands and staffs, and the king and those closest to him, convincing them of the omnipotence of the Allied armed forces. Fueled by Allied propaganda, the leadership in Rome fixed on the idea that vast Allied armies would land north of Rome, covered by clouds of fighters and bombers and supported by fleets of battleships and cruisers. Now Badoglio believed the Allies could not only cancel the airborne operation but also shift Avalanche, with the convoys already at sea, north to the vicinity of Rome. This was a flight of fancy, but the Italians were accustomed to living in an imagined world.

Eisenhower left Algiers for Amilcar early on the morning of 8 September. Just after his departure, Badoglio’s renunciation of the pact and Taylor’s initial advisory crossed Smith’s desk. For two and a half hours Smith weighed the options; he recognized Eisenhower’s sensitivity to depending on direction from above, but he also knew Eisenhower would not carry out the announcement without approval. He decided to dispatch the Rome correspondence to the CCS, together with a request over Eisenhower’s signature for advice on whether AFHQ should proceed with the armistice announcement “for the tactical deception value.” He added that Giant II would probably be canceled.15 Smith had never placed much store in Italian fighting capacity. The Italian Seventh Army in Calabria, Campania, and Puglia lay interposed between the German forces in the south. Smith and Eisenhower reckoned an Italian announcement of an armistice would throw the Axis defense into confusion, and even if the Italian troops did not fight, their deployments would at least obstruct German freedom of action. That, in combination with the Salerno landings and the Rome air operation, might just stampede the Germans into a withdrawal.16 The Allies—placing too much faith in Ultra—were also victims of self-deception. Reality now hit home. Faced by the Italian double cross—which should not have come as any great surprise—Smith advised proceeding with the announcement.

When Eisenhower read the bundle of dispatches from Algiers, his face flushed as pink as the incoming message form. He picked up two pencils in succession and snapped them in two; then he stamped, “expressing himself with great violence.”17 He was nearly as peeved at Smith for asking for guidance as he was with Badoglio. Eisenhower dictated a scalding reply to Rome, stating his intent to broadcast the announcement as planned; if the Italians refused their cooperation, he threatened “to publish to the world the full record of the affair.”18 He ordered Castellano’s return to Tunis, hoping he could influence Badoglio.

Communications in the theater always proved problematic. Alexander issued Ridgway an order canceling Giant II but received no confirmation. Eisenhower ordered that Lemnitzer rush to El Aouina airfield in Sicily. In a commandeered British Beaufighter, Lemnitzer flew to Sicily, but the pilot got lost; he skirted the coast until he sighted circling transport aircraft. Dropping down to treetop level, Lemnitzer fired a flare gun. The controller saw the flare and correctly interpreted its meaning, and the takeoffs ceased. A disaster was averted by the narrowest of margins.19

Smith’s cable got a lot of very important men out of bed in Washington. Churchill, visiting the White House after the conclusion of the Quebec conference, expressed no shock. “That’s what you would expect from those Dagoes.”20 Both political heads approved Eisenhower’s announcement. At 6:30 that evening, on schedule, Eisenhower made his announcement on Radio Algiers.

Unreality still reigned in Rome. The Italian leadership understood Eisenhower would make his announcement regardless of their actions. Taylor told them as much. They also knew the Allied invasion was imminent; that morning, 8 September, the Allied air forces launched a massive decapitation raid on Kesselring’s Frascati headquarters. Still the Italian leadership dithered. The king believed he still possessed an out: if the Allied invasion triggered a German withdrawal from Rome, the armistice was on; if not, the king believed he could repudiate the surrender, renounce Badoglio, and continue cooperating with the Germans. Only after Eisenhower made his broadcast did the king convene the Crown Council. The king, “a pale, worn-out Badoglio,” the foreign minister, the service chiefs, and Carboni considered their options. They called in Marchesi, the officer best informed on Allied thinking. Amazingly, the majority supported continuing with the Axis. Only the lowly major saw the obvious flaw in their hallucination. The Germans would stage their putsch whatever course the Italians took. Deciding to save whatever face he could, the king concluded that Italy could not change sides again and ordered Badoglio to make his announcement.

The Italian command preserved the façade of cooperating with the Germans to the end. The only planning the Italian armed forces engaged in involved meeting the Allied invasion; the only planning in the government centered on escaping Rome. The lone orders that went out facilitated the flight of the king and his convoy of seven vehicles. Otherwise, Italian forces in Rome acted on a single standing order: “in no case … take the initiative in hostility against the German troops.”21

As Smith relayed to Ismay, “the armistice put the Hun into a complete flap for a couple of days.”22 There was plenty of confusion to go around, and in truth, Kesselring did a far better job of cutting through the fog than did AFHQ. The German command structure in Italy suffered from its own internal divisions. Hitler and the high command linked Italy—especially northern Italy—to the defense of the Balkans. A withdrawal to the Alps condemned Croatia and Yugoslavia, with the attendant fear of a domino effect knocking out Germany’s satellites—Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Additionally, the agricultural produce and industries of the Po Valley and northern Italy represented valuable economic assets. As early as May, Hitler became convinced that Italy was seeking a separate peace and that fascism in Italy—always the product of a single man—might collapse. Any hint of an Italian betrayal would trigger immediate German action. Units were withdrawn from Russia, and a special staff was created to plan the takeover in Rome and the occupation of Italy.23 On 25 July the Germans still had only a handful of divisions in Italy; that situation radically changed.

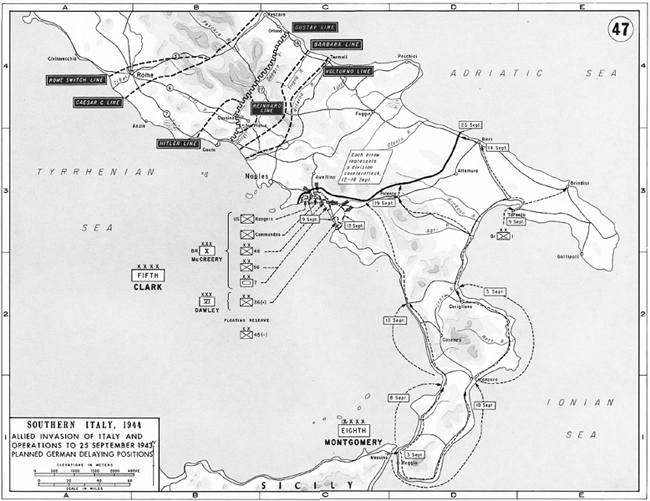

Rommel received command of Army Group North and the task to prepare plans for the defense of Italy. In July he concluded that German forces “cannot hold the entire peninsula without the Italian Army.”24 Rommel planned on a withdrawal north of the Apennines in defense of the Po Valley. Because of Kesselring’s warm regard for his allies—many considered his well-known optimism his greatest weakness—and his long-standing rivalry with Rommel, he remained outside the planning loop. Operation Achse (Axis), finalized on 1 August, called for a coup and reinstatement of a fascist regime, the disarming of Italian forces in the north, and a withdrawal from central and southern Italy. Sicily convinced the German high command that the Italian armed forces would contribute nothing in the face of an Allied invasion. In mid-August Kesselring received directives to initiate the retreat in the event Italy moved toward a separate peace.25 These were the directives intercepted by Ultra. Those orders still stood when Clark’s Fifth Army hit the beaches at Salerno on 9 September.

Unhurt but badly shaken by the attack on his headquarters, Kesselring anticipated Allied landing operations in the vicinity of Rome. On the night of 8–9 September the German embassy burned documents and evacuated most of its staff. LTC Giacomo Dogliani, liaison officer to Kesselring, made a courtesy farewell call to Frascati on the morning of 9 September. Kesselring’s chief of staff asked Dogliani for “one more favor. Persuade your headquarters not to oppose the withdrawal of the German troops from Rome.” Kesselring then intervened, motioning to say no more.26 Salerno allayed his anxiety. Kesselring implemented Achse but asked permission to hold in place and defeat the Allied invasion. Berlin wired concurrence.

Smith always regretted the cancellation of Giant II. It was possible the airborne operation might have exploited the confusion and prompted Kesselring’s execution of the planned evacuation of Rome. Giant II could have steeled the Italian leadership. The first possibility appears more plausible than the second. Isolated pockets of popular resistance sprang up in Rome, some of it fierce, but in two days the Germans pacified the city. The vast majority of the Italian army either confined themselves to barracks or deserted, proclaiming tutti a casa—“let’s all go home.” Most of the senior officers abandoned their posts and surreptitiously slipped away. “I remain convinced, as do the officers of the planning staff,” Smith told Castellano in December, “that this plan could have been carried out and would have been successful had there been in command of the Italian divisions around Rome an officer of courage, firmness and determination who was convinced that success was possible.” Clearly, none of the Italian generals possessed any of these qualities. “It might be,” he conceded, “that I did not accurately evaluate the situation as it existed on September 3rd.”27

The Germans quickly roped off the British lodgment and viciously counterattacked against MG Ernest Dawley’s VI Corps. Smith authored a situation report to the CCS and BCOS on 9 September. AFHQ had no news from the severely pressed VI Corps. He explained, “demolitions and the Germans’ rear guards will prevent [Montgomery] being any real help … for some days.” On the plus side, Smith told of the rush of the British First Airborne Division into Taranto and the securing of the Italian fleet. “Clark’s buildup,” he warned, is “now a critical factor.”28 The Wehrmacht, including three of the four divisions allowed to escape Sicily, exploited the seven-mile gap between the Allied forces. By D+3, the situation appeared dire enough for Clark to consider extracting Dawley’s corps and moving it to the British sector—a double amphibious operation fraught with danger. Only Allied firepower staved off disaster. Tedder and Cunningham threw in everything they could get their hands on. The Northwest African Air Forces, including B-17s, dropped an impressive 3,020 tons of ordnance on the Germans, but this paled in comparison to the 11,000 tons of accurate naval gunfire directed at the enemy’s armored spearheads and artillery.29 Fortunately, the Eighty-second had not been used in Giant II; the paratroopers were airdropped near Paestum on successive nights and played a vital role in shoring up the defenses. AFHQ informed the CCS on 13 September that the situation remained “touch and go” and the next week would be “one of anxiety.” Three days later, at the behest of Alexander and Clark, Eisenhower sacked Dawley for “extreme nervousness under prolonged strain” and replaced him with Lucas.30 Dawley paid the price for Clark’s inept planning; so too would Lucas at Anzio. The U.S. Army did not flinch from firing corps commanders; dismissing army commanders proved another story.

With AFHQ, the Allied strategic air forces, and a bulk of the combined fleet preoccupied with saving Avalanche, the Germans began what turned out to be another brilliantly executed set of evacuations from Sardinia and Corsica. On Sardinia, despite a huge advantage in manpower, the Italians did nothing. On 9 September the Germans seized the anchorage at Maddalena and completed their withdrawal to Corsica in six days. Berlin ordered German forces out of Corsica on 12 September. Employing air transport and an improvised fleet of ferries, the Germans evacuated from northern ports as French troops entered from the south. Despite Allied control of the air and sea and exceptionally good intelligence, by the first week in October another 30,000 German troops, with arms and vehicles, completed their escape and joined the fight in Italy.

The crisis at Salerno passed, and on 16 September lead elements of the British Fifth Division contacted a Fifth Army patrol forty miles southeast of Salerno. AFHQ made apologies for Montgomery’s tardiness, but privately the Americans fumed. With typical Teutonic efficiency, the Germans destroyed the few improved roads and communications, and Montgomery’s forces advanced through very tough terrain. But the fact remained that, in the two weeks following the landings, the Eighth Army had faced a single panzer division, losing sixty-two killed in action and capturing a mere eighty-five Germans. The Canadian First Division made no contact with the enemy from 8 to 18 September. Illustrative of the speed of the German drawback and Montgomery’s dilatory advance, the first link actually involved bored journalists in search of copy.31

Eisenhower became quite expansive. On 20 September he predicted the Germans were “too nervous to stand for a real battle south of the Rome area.”32 Churchill wired congratulations on “the victorious landing and deployment northward of our armies” and reminded Eisenhower of what Wellington had remarked after Waterloo: “It was a ‘damned close-run thing’ but your policy of running risks has been vindicated.” The next day Marshall “took the starch out of Ike.” The chief wondered whether Eisenhower, once he had Naples “under the guns,” should bypass the city and make an amphibious dash for Rome. An incredulous Eisenhower struggled to reply, aided by Smith. Eisenhower “grieved to think that General Marshall does not give him credit for cracking the whip. [It] caused him a great deal of mental anguish,” Butcher recorded. “We have the paradox of the Prime Minister applauding Ike’s willingness to take risks while General Marshall … criticize[s] him.” During the Salerno crisis, the CCS finally relented and gave Eisenhower those three bomber groups AFHQ had been requesting for weeks. Beetle and Butcher tried to buoy up Eisenhower. Smith half-jokingly thought he should form another staff section with the sole task of keeping the home front constantly frightened. Struggling again to explain to Marshall the impossibility of staging any amphibious operation for at least six weeks—the time required for withdrawing, refitting, restocking, and redeploying landing craft, if they were available (which they were not, because the Germans’ destruction of the infrastructure meant they remained tied to supply functions)—Eisenhower and Smith engaged in a little gallows humor. When Butcher suggested the army should alter its training methods and teach GIs to walk on water, Smith retorted that they already could, but not with full packs.33

Smith understood the root problem remained AFHQ’s inability to direct operations, and as long as that state of affairs persisted, Eisenhower could expect more “mental anguish.” On 20 September Smith inaugurated a new scheme asserting the supreme commander’s authority. “Beetle states in front of British at his 12 noon conference,” Hughes recorded, “that ‘The duties and responsibilities of the C in C must be redefined.’” Hughes spoke for many when he wondered, “Why should we worry when apparently even Ike doesn’t know what he can tell the other C-in-Cs?”34 Nothing came from Smith’s initiative because Eisenhower never cracked the whip with any real conviction.

While Smith troubled himself over Eisenhower’s nebulous hold on supreme command, he congratulated himself on the excellent work of his staff. For him, the inauguration of the Italian campaign marked the coming-of-age of his headquarters. Even at the height of the emergency, Smith told Ismay, “our party here is going very well” and said he retained “restrained optimism” Avalanche would yet succeed. He asked Ismay to come to AFHQ “to see real Allied cooperation and coordination.” He boasted, “We still have it and always will as long as Ike is in the saddle.”35 He carried on in a similar vein to Mountbatten after the Germans pulled back. “I tremble to think what our present situation would be if the armistice had not come off but the results so far have been tremendous.” He pointed to the long train of successes. “We already have BUTTRESS [the toe], GOBLET [the instep], MUSKET [Taranto], and BRIMSTONE [Sardinia]; that operation FIREBRAND [Corsica] is being done for us and we are about to move into Corsica and that we have AVALANCHE securely, not to mention the fleet, it certainly justifies what the newspapers call ‘a feeling of restrained optimism.’” He continued, “I am so desperately proud of this organization that I am quite likely to slop over, but during AVALANCHE and the intricate maneuvering incident to the Italian armistice, I had the supreme pleasure of seeing what started out to be a complicated, unwieldy, creaky machine ticking away like a Swiss watch with every staff division doing exactly the right thing at the right time, constantly thinking ahead and meeting every emergency with a little time to spare.” He called it “the high point in my career.”36

And never had he stood higher in Eisenhower’s estimation. “If ever I should write any memoirs,” Eisenhower wrote to McNarney, “I should certainly have to devote a full chapter to the debt I owe to Smith. He is a fellow who carries a tremendous load and does it so ably as to excite my admiration every day.”37 His stock was pretty high in Washington too. Stimson’s assistant, John J. McCloy, informed Smith, “You are getting a big reputation [in the War Department].” In July Smith received his first Distinguished Service Medal for welding the machinery of the joint and combined staffs as secretary, followed by a second in August for his work organizing and running AFHQ. Amidst all the fanfare, he also received some sage advice from Pa Watson. “Hope you are taking your vitamins,” Watson chided, “and keeping your feet on the ground.”38

Roosevelt and Churchill told Stalin in August 1943 that an invasion of the Italian mainland would trigger either a German coup and the “setting up a Quisling Government of Fascist elements” or the collapse of the Italian government “and the whole of Italy pass[ing] into disorder.” Both occurred.39 The king’s and Badoglio’s prevarications and procrastination ensured that the Italian “betrayal” immediately transformed Italy into a battleground. Victor Emmanuel mistrusted the army and dreaded unleashing a popular uprising, for fear it would spark a communist-led revolution and end the monarchy. The prostrated communists offered no threat. The army’s orders to avoid any confrontation with the Germans until after the armistice merely delivered unliberated Italy over to the vengeful Germans, who acted with their customary vigor in freeing Mussolini and placing him at the head of the Italian Social Republic (RSI), a puppet regime legitimizing the German occupation and the continuity of the Axis. The partisan uprising did occur in central and northern Italy in the guise of the clandestine Committee for National Liberation (CNL), an umbrella group that emerged to resist the German occupation and the RSI. Although monarchists, Catholics, and former officers took to the hills, the CNL remained dominated by leftist and republican elements. The king and his motley collection of hangers-on made good their escape, but the “flight to Brindisi” virtually ensured a postwar Italian republic.

Except for signing the long-terms surrender document—which he could not avoid—Eisenhower steered clear of any involvement with the Italians. Smith negotiated with the Brindisi government and formed the structures that transitioned Italy from an occupied territory to an Allied military associate. In addition, because of the chronic delay in achieving agreement among Washington, London, and now Moscow, his voice emerged as the most prominent in establishing policy.40

Eisenhower and Smith greatly exaggerated the support they expected from the Italian armed forces. The day after the Salerno landings, Smith urged Marshall to prod the president and Churchill into recognizing the Badoglio government, encouraging “the Italians to oppose with the fiercest possible resistance every German in Italy.”41 The next day AFHQ conveyed a message directly to Badoglio, stating, “The whole future and honour of Italy depends upon the part which the armed forces are now prepared to play.”42 The following day the two governments made public a letter to the marshal calling on Badoglio to lead the Italian people against the German invader. All this amounted to little. The Italian ground forces in southern Italy, Sardinia, and Corsica simply disintegrated. The portions of the fleet stationed in Ligurian and Tyrrhenian bases made for Oran, and those in Taranto and Brindisi headed for Malta. About half the Italian fleet made their escape. On 13 September—the day the Germans nearly split the Salerno bridgehead—Smith sent Mason-MacFarlane to Brindisi as head of a military mission. Murphy and Macmillan went along. The day before, Smith had brought his “pet Wop” Castellano to Algiers as head of an Italian military mission at AFHQ. “So you see,” he wrote to Ismay, “our two ring circus has developed first into three rings and now four rings, counting the French and Italians.”43

The Brindisi party consisted of the king, Badoglio, Crown Prince Umberto, Ambrosio, Roatta, and a collection of generals and admirals. All the civilian agencies remained in Rome. The Italians possessed few bargaining chips other than their “unchallenged claim of legality” against the republican regime set up by the Germans. Badoglio also maintained that Italy “is now in a de facto state of war with Germany.” Acting on Smith’s instructions, Mason-MacFarlane dangled the possibility of the Italian government gaining cobelligerent or military associate status and administrative control over the four liberated provinces in southern Italy, in exchange for pledges to broaden the government, restore the constitution, and hold postwar elections. Badolgio must also accept AMGOT’s jurisdiction over areas not placed under the control of his government and an armistice commission to oversee Italian compliance with the surrender terms. To make the arrangement more palatable, Mason-MacFarlane opened but never pushed the question of the king’s abdication.

After talking to Murphy and Macmillan upon their return to Algiers on 18 September, Smith drafted a long report to the CCS and BCOS. He pointed out that AFHQ intended to use Italian forces in Sardinia and Corsica for coastal defense and portions of the fleet for transport. Smith, in Eisenhower’s name, requested that the Badoglio government receive “some form of de facto recognition … as a co-belligerent or military associate.” Recognizing that such a policy shift was “not at all consistent with the provisions of the long terms armistice” and that it exposed the governments to “considerable opposition and criticism,” he recommended that “the burden be placed upon us, on the grounds of military necessity, which I am convinced should be the governing factor.” The cable also asked for a decision on the requested modifications before Eisenhower met with Badoglio.44

Eisenhower did not like the bit about AFHQ accepting blame for cutting a deal with the Italians. On 19 September—now back at his advance command post in Tunisia after visiting the Salerno beachheads—Eisenhower drafted a new cable. He pointed to two paths the Allies could take in future relations with the Italians: either accept Italy as a military associate and strengthen Badoglio, or assume the heavy liability of establishing an Allied military government. Eisenhower “strongly recommended the first.” If Smith concurred, he wanted the cable forwarded to London and Washington.45 It went out the next day.

Smith’s report and Eisenhower’s “either/or” request prodded Washington and London to finalize the terms of surrender and define Italy’s future status. Though admitting the long terms appeared “somewhat superseded,” the British insisted on their use in the final Italian surrender.46 Roosevelt felt that events in Italy made the long terms “completely superfluous” and wanted the military armistice lightened “in order to enable the Italians, within their limited capacities, to wage war against Germany.” Stimson liked nothing about “this Italian business” and influenced the president to grant only temporary approval for AFHQ’s withholding of the long terms, pending further instructions. He did offer AFHQ the power to modify the exactions of the surrender if Badoglio agreed to a declaration of war; only then could Italy be considered a cobelligerent.47

Acting on Roosevelt’s instructions, Smith directed Mason-MacFarlane to arrange an Eisenhower-Badoglio meeting in Malta and warned him against mentioning the long-terms armistice, “as we are instructed to hold it in abeyance.” AFHQ instructed that these concessions had no bearing on the requirements for a return to constitutional government in the postwar period.48 Smith then modified the original title and preamble containing the words “unconditional surrender.” After Badoglio signed the “military” surrender, the Italians would be told to expect from time to time additional terms or directives on political, financial, or economic matters under the provisions of the 3 September surrender document. Smith thought Badoglio would accept the two-tier approach.49

Macmillan came to the same conclusion. He notified London that Badoglio protested not the harsh terms but the language of the armistice. Advised that Badoglio would sign any document placed in front of him, the British renewed their pressure for the long terms. The Soviets likewise considered “it necessary to expedite the signature of the detailed armistice terms … necessary in view of the situation existing in Italy at the present time.”50 Roosevelt gave in and authorized Eisenhower to sign the long terms.

Noting AFHQ’s preoccupation with Italian affairs, de Gaulle exploited the situation by manufacturing another crisis. Citing the difficulties involved in dealing with communist resistance elements—and Giraud’s political ineptness—de Gaulle insisted that the forces operating in Corsica come under his command. On 25 September he placed before the FCNL proposals to end the system of dual command and form a single executive. Giraud’s meek defense convinced the majority to side with de Gaulle. Giraud again played into de Gaulle’s hands; he signed a document that effectively deprived him of his nominal authority as commander in chief. Long favoring a greater role for de Gaulle and anticipating a settlement of the French leadership question, Smith raised no objections to Giraud’s ouster as copresident.51

As de Gaulle calculated, Smith possessed no time to treat with the French. The entire deal with the Italians appeared to be in trouble. On 26 September he received instructions from Washington reversing American policy on the long-terms document. The same day Mason-MacFarlane reported that Badoglio had agreed to Smith’s agenda and volunteered to come to Malta. He also indicated the king had suddenly taken refuge behind the constitution. He could not declare war on Germany, since only a constitutionally established government could do that. Victor Emmanuel also told Mason-MacFarlane that he expected to dump Badoglio. He played the communist card, warning, “it would be most dangerous to leave the choice of postwar government unreservedly in the hands of the Italian people.”52 Accompanied by Murphy and Macmillan, Smith flew to Brindisi the next morning and explained to the Italians there would be “no quibbling … over details”; they must sign the long-terms surrender.53 Smith’s first acquaintance with Victor Emmanuel and Badoglio convinced him “there was something fundamentally lacking in all the top men.”54 He told reporters, “the Italian government, at the present time, consists of the king, Marshal Badoglio, two or three generals, and a couple of part-time stenographers. The day that I was there, a couple of cheap help from the Foreign Office (an under-secretary or two) came down from Rome on foot.” Victor Emmanuel, once described as Italy’s “moron little king” in an AFHQ propaganda broadcast, appeared “absolutely pitiful,” in Smith’s opinion. Badoglio “has been a good general but he was an old man—without decision—and given to crying.”55 Whereas the marshal proved malleable, the king refused to declare war on Germany or promise free postwar elections. Smith left with what he came for, however. After some typical Smith bullying, the king finally authorized Badoglio to meet with Eisenhower in Malta in two days’ time and sign the long terms. “The King-Badoglio government is a pretty weak affair,” confessed Eisenhower, “yet it is the only medium through which Italians can be inspired to help us.”56

Badoglio, himself the object of a black propaganda blitz, requested that the comprehensive terms of the surrender be withheld from the public. He thought if the Italians knew the full extent of the capitulation, they would reject his government. Smith entertained the same concerns and worried that release of the surrender text would provoke resistance and make the work of the Control Commission more difficult. Smith promised to raise the issue with Eisenhower and intimated the Allies would probably withhold publication.

The surrender itself proved anticlimactic. Aboard the battleship Nelson in Valetta Harbor, Eisenhower and Badoglio affixed their signatures to the “Instrument of Surrender of Italy.” Cunningham, Alexander, Smith, Murphy, Macmillan, and an array of lesser lights looked on. After the signing Eisenhower handed Badoglio a letter, written by Smith, that stated, “several of the clauses have become obsolescent or have already been put into execution,” and others exceeded the current powers of the Italian government. Future conditions remained contingent on “the extent of cooperation by the Italian government.”57 Badoglio appealed, asking that Eisenhower alter the document’s title and remove the first clause containing the phrase “unconditional surrender.” If the terms became public, his government “would be overwhelmed by a storm of reproach.” Eisenhower promised to consult the political heads. As “a matter of the utmost urgency,” the next day Smith requested acceptance of his amended title and rewording of Article 1 and suppression of the document “as absolutely vital to our success in Italy.”58 After an exchange of cables, Churchill wrote to Roosevelt on 4 October, “now that Uncle Joe has come in with us about Italian Declaration … there should be no nonsense about terms until Rome is taken. It seems to us high time that the Italians began to work their passage.”59 The text of the Italian surrender remained unpublished until November 1945.

For a month Marshall had been requesting Smith’s return to Washington for discussions concerning future operations in Italy and manpower and supply requirements, but the unsettled Italian situation and the expected move of AFHQ to Italy kept Smith in the theater.60 Still smarting from Marshall’s criticism of his lack of boldness, Eisenhower wanted clarification on how the Italian campaign could most effectively contribute to the future cross-Channel operation (Overlord). He thought the best solution would be to center all efforts on preserving the initiative in Italy. At the end of September he expected to be “called home for consultation.” When the call came and Marshall asked him to come to Washington for talks on “matters pertaining to your theater,” Eisenhower begged off. On 1 October the Allies secured Naples, and three days later Eisenhower cabled Marshall, “Alexander and I both believe we will have Rome by [the end of] October. There is nothing particularly bothering us at the moment,” he explained, “in spite of the delicate nature of the Italian political problems which Smith handles so well, [so] I think he should come home for a very brief visit in order that our planning for the winter campaign may dovetail perfectly with the larger projects you have in view.” He said Smith represented “the only one I have that can come to see you to make sure that we are on the right track.” He hoped Smith could conclude his business in two or three days. “I sorely need him back as soon as possible.”61

Operational matters did not occupy much of Eisenhower’s attention. He casually informed Marshall, “We will have Rome by October” and noted, “the greatest possible assistance we can give you is to conduct a vigorous fall and winter campaign to include the capture of the Po valley, from which position we can threaten and actually stage diversionary operations into southern France.”62 Although couching his language in terms of how expanding operations in Italy supported Overlord, Eisenhower’s primary interest rested in safeguarding his own theater.

His personal prospects preoccupied him far more. On 1 October the navy secretary, Frank Knox, stopped by El Aouina and informed Eisenhower over lunch that the political heads had decided at Quebec that Marshall would command the cross-Channel operation. Speculation on the appointment prompted a great deal of press. For this reason, according to Knox, the president had ordered a news blackout, and no announcement appeared in the minutes of the Quebec conference. Nonetheless, Knox assured Eisenhower, it was “official.” More troubling was the news that, according to Knox, Eisenhower would take over as army chief of staff.63 Eisenhower immediately called Smith, told him the news, and informed him he was sending Beetle to Washington for talks with Marshall; he then forwarded two letters outlining the points he wanted covered with Marshall.

On 3 October Mountbatten came through on the way to his new theater command. He disclosed a slightly different take on Quebec. Under pressure from Roosevelt, Stimson, and Hopkins, Churchill had bent and agreed that Marshall should command Overlord, and as a sop to Brooke, Hopkins suggested the theater command in the Mediterranean should be British. That left Eisenhower without a command. Mountbatten thought the chances were good that Eisenhower would return to Washington as chief of staff. “Beadle [sic] is being sent home to see what can be done about protecting Ike from becoming US Chief of Staff,” Hughes wrote to his wife. “Ike wouldn’t like that job—furnish what Marshall wants, do as Marshall says. What Beadle can do is more than I can figure out, but he has gall, nerve, and can talk fast.”64

To make sure they were on the same page, Eisenhower returned to Algiers for the first time in a month to brief Smith before he left. In front of Butcher they hashed out all the possibilities. Just about the last thing Eisenhower wanted was a “political” job in Washington, especially becoming the boss’s boss. Then there was the equally daunting issue of dealing with another old boss, MacArthur. Eisenhower much preferred commanding an army group under Marshall in Overlord. He told Smith that if the topic came up in his discussions with Marshall, he should convey that message as discreetly as possible. Eisenhower also asked Smith to go to bat for Patton. Despite the Sicilian outrages, Eisenhower had just recommended Patton for an army command in Overlord.65

Smith’s “official” agenda was lengthy. Eisenhower wanted Smith to convince Washington officials of the paramount importance of propping up Badoglio as “the only leadership in Italy around which anti-Fascist elements can rally.” Smith should also make the case for retaining air and airborne units and landing craft in the Mediterranean. Eisenhower envisioned running some amphibious operations to speed the advance up the Italian boot. Questions surrounding the future air command structures in Europe also loomed large. Eisenhower opposed Arnold’s idea of creating a single supreme commander for air to conduct the strategic bombing campaign. Spaatz would also go to Washington and settle matters pertaining to the establishment of the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy. Smith’s job focused on defending a theater commander’s control of air assets. Based on Mediterranean experience, any air commander should coordinate strategic bombing, but Eisenhower considered it more important that he understand the requirements of close air support. Since he considered Tedder the best man for the job, Eisenhower offered to surrender him. As he told Marshall, “our team here has become so well solidified that with Smith and me on the job we can now accept substitutes in some important places.”66 Eisenhower also asked that Smith clarify the theater’s opposition to McNair’s plan for reducing the combat strength of American divisions by 2,000 men. Also related to the manpower question, Eisenhower insisted the theater’s “replacement situation should be thoroughly considered.”67 On 5 October, his forty-eighth birthday, Smith boarded his aircraft for the flight to Washington. Clearly, his mission would take more than two or three days.

Aside from the tasks assigned by Eisenhower, Smith composed his own long list of questions. Many involved dealing with the French and Italians: the impact of Italy’s elevation to cobelligerent status on U.S. policy, the vital importance of keeping the Italian surrender terms under wraps, the implications arising from recent developments between de Gaulle and Giraud, reequipping and training French forces according to the revised Quebec estimates, and finalizing civil affairs policy and organizational plans for military government and the Control Commission in Italy. Others centered on operational issues: amphibious operations, if any, up the Italian boot and their timetable; the invasion of southern France in support of Overlord, an operation Eisenhower thought little of; the effectiveness of airborne units to date and their future use; and AFHQ’s opposition to British schemes for operations in the eastern Mediterranean. Smith also needed guidance on a number of issues related to special operations in the theater: how to correlate expanded OSS operations in southern France, northern Italy, and the Balkans with those of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE); the degree of importance attached to special operations, which in turn involved the employment of military, especially air, assets; and whether special operations should be directly under military command.68

Before he tackled his official chores, Smith went into undercover mode, tapping into his many sources to try to determine what the future held for Eisenhower. King and Arnold vigorously opposed any suggestion Marshall should leave Washington. Stimson’s voice was strongest in making the case for him to go to Europe. Among the senior soldiers he talked to, all believed Marshall would head Overlord, and speculation centered on whether Eisenhower, Somervell, McNarney, or McNair would replace him. Following conversations with Marshall, Smith concluded the chief wanted Eisenhower to stay in the Mediterranean. On 10 October Smith wrote a cryptic letter to Eisenhower, informing him, “you can now concentrate on long range plans.”69

Hughes detected plenty of indications that Eisenhower planned to leave the theater. “Ike wants me to take Kay [Summersby] with car thrown in. He doesn’t want to be Chief of Staff of the US Army.”70 Smith’s letter raised his hopes. For one thing, he was relieved that Smith was representing his interests. “Every time you go away,” Eisenhower confided in Smith, “I learn again how much I depend upon you.”71 As he explained to the wife of an old army buddy, Beetle was “by all odds the most competent and marvelous Chief of Staff that any Commander was ever lucky enough to have. I don’t know how I would carry along without him.”72 Eisenhower began to fret that whichever appointment he received, he might lose Smith.

With that bit of business out of the way, Smith systematically worked through his checklist of assignments. Much of his time was spent handling problems left unsettled by the Italian surrender. On 11 October Smith met with the president and Hopkins. The Malta surrender and the amended surrender conditions had not closed the book on questions pertaining to enforcement of the settlement. Spurred by Churchill, Roosevelt felt no compulsion to cater to the Soviets on the actions of the Allied Control Commission in Italy. Roosevelt stood ready to accept Smith’s recommendations. Provisions for control of the Italian fleet remained purposely ambiguous. Churchill wanted a free hand in the disposition of Italian warships; at the very least, he wanted to use the issue as a bargaining chip to induce the Italians to declare war. Now Churchill again raised objections to eliminating the “unconditional surrender” language from Article 1, since it impacted the retention of Italian warships. Roosevelt and Hopkins were prepared to leave matters where they stood. So was Smith.73 “The matter is becoming too complicated for me to handle at long range,” Smith informed Eisenhower. “At McCloy’s suggestion, I am filing with the JCS the document as originally signed without any amendments or corrections whatever leaving it to the CCS Secretariat to struggle with matters of protocol.”74

Smith instructed Whiteley to keep him informed on developments in Italy. On 13 October Badoglio finally made a declaration of war, and Eisenhower ordered Whiteley to expedite Smith’s plan for a military government in Italy. Smith orchestrated the selling of the program in Washington. After his trip to Brindisi, Smith had decided the Italian government was incapable of exercising any measure of effective control and that AMGOT and the Control Commission would administer all liberated territories until an Italian government could function in Rome.75 Smith’s plan envisioned three stages. As long as operations continued, ultimate authority remained in Eisenhower’s hands; when the Badoglio government proved ready to assume a more active role, supervision would pass to the Control Commission. At that point the Advisory Council, consisting of high commissioners from the United States, United Kingdom, USSR, France, Greece, and Yugoslavia—representatives of all the powers formerly at war with Italy—would operate under the day-to-day management of AFHQ’s designated deputy. This third period would begin after the cessation of hostilities. Until then, Italy would be divided into three zones. In the south, the so-called king’s Italy took shape in the four Apulian provinces; these areas were under the titular control of Badoglio, with the military mission acting in liaison and supervisory roles. Farther north, in the intermediate zone behind the front, fell those territories under the direct administration of the Allied Control Commission. As the front moved north, so would the zonal boundaries. The final area, the combat zone, remained under AMGOT, directly answerable to Alexander.76

The military government program suffered from a host of problems. With the organization settled—the mechanism received the approval of the Allied foreign ministers in Moscow at the end of October—Smith turned to staffing the new structures. Washington only very belatedly placed any priority on military government. Just about the only thing Stimson, McCloy, and Morgenthau agreed on was that they disliked the name AMGOT. They thought it sounded too much like OGPU and Gestapo—secret police.77 The acronym remained, and given the advanced age of its senior leadership, AMGOT took on the meaning “Aged Military Gentlemen on Tour.” The Americans still encountered problems manning AMGOT. Hilldring complained, “I have a lot of willing workers who don’t know more about military government than what they read in books.”78 The bigger issue revolved around achieving some semblance of balance between the British and Americans in senior positions. Smith tried to lever McCloy out of Washington as head of civil affairs in AFHQ. As McCloy recounted, he “put it to the Secretary [Stimson] as strongly as I knew how but no luck.”79 Smith asked for Hilldring, who complained of suffering from a dose of “Pentagon pallor” and lobbied hard to escape the War Department, with no luck. After McCloy and Hilldring, Smith had very few options. Eisenhower suggested LTG Kenyon Joyce, whom he had served under at Forts Lewis and Sam Houston. Joyce possessed no experience, but Eisenhower thought highly of him. Smith engineered his appointment as Eisenhower’s deputy to the Advisory Council, and another aged military gentleman joined the team on 7 November. Rennell remained chief of civil affairs with an American deputy, BG Frank McSherry. In Smith’s view, military government was a misnomer. Rennell and Joyce served as his deputies for handling Italian affairs as directed by AFHQ.80

The looming manpower crisis triggered the main buzz in the corridors of the Pentagon. Manpower and supply—the two spheres that bestowed the least credit on the army—suffered from almost identical evils, the origins of which lay in the incomplete reorganization of the War Department in 1942. AEFHQ and Pershing’s War Department model contained a separate division for training. Under the 1920 NDA structure, G-1 and G-3 shared responsibility for training. Marshall’s restructured WDGS not only retained this disconnect, but it also widened it. The War Department’s manpower plan called for half the men deployed overseas to enter the theater as members of integrated and trained formations; these units were organized and trained by AGF, AAF, and ASF. The other half would go overseas as individual replacements. Replacements would flow into existing units based on expected rates of attrition. The system suffered from imbalances from the beginning and never recovered. First, planners greatly exaggerated the percentage of manpower allotted for combat units. Then Torch and North Africa pulled troops from training divisions in the United States as replacements. The critical shortages of service personnel required a number of alterations in the troop basis. The rush of service troops to North Africa and the expedient formation of provisional units in the theater gave the appearance that surplus manpower had been sucked into the rear or lost in the pipeline. Sicily and the movement into Italy placed additional strains on an already faltering system. The army’s miscalculations on manpower requirements exacerbated the problem. Responsibility for retraining replacement officers and men placed in redundant or superfluous military occupation slots fell to the theater commands, which suffered under the same organizational constrictions that plagued the War Department. A whole parade of officers toured the theater and always returned to Washington with stories of the unnecessarily bloated rear areas and the extravagant use of officers in headquarters. Marshall saw no need for an independent training command; instead, he placed the organizer of the restructured WDGS, McNarney, in charge of overseeing the army’s manpower program. As another by-product of the bureaucratic infighting between the WDGS and Somervell, no agency had control over the replacement structure. Somervell argued for a separate manpower and training command under ASF’s superintendence, but McNarney continually blocked any resolution of the standoff. The U.S. Army fought the entire war without resolving the dispute. As a result, the replacement structure became an administrative black hole and a black mark on the record of the U.S. Army.81

The War Department’s misbegotten manpower program sparked a public outcry, prompting congressional action. Parents complained about their sons languishing for months in retraining depots in active theaters. Others complained that their teenage sons went forward after only a few weeks’ training. By summer 1942, the War Department admitted its gross underestimate of manpower requirements and projected serious shortages. As a remedy, the army called for the drafting of eighteen-year-olds and drastic reductions in time in training. In mid-September McNarney went to Capitol Hill to explain the factors behind the projected personnel shortfalls. McNarney sidestepped the issue, affixing blame not on War Department policies or any of his agencies but on the theater commands, especially AFHQ and NATO. Marshall, predisposed to blame rear-area commands, accepted McNarney’s whitewashing. On 13 October he placed the fault on NATO and warned Eisenhower that he “must get to the root of the problem immediately.” The next day he accused NATO and the SOS of “skimming the cream” of replacement personnel, depriving combat units of the most qualified men.82 Fortunately for Eisenhower, three days earlier Hughes had submitted a comprehensive study of theater manpower allocations that offered proof to the contrary. Anticipating this turn of events, Smith took pains to meet with Marshall and McNarney, explain the unique problems the theater faced, and defend AFHQ’s record. Clearly, his efforts neither pacified Marshall nor deflected McNarney.83

By 13 October Smith thought he was “about finished here” and anticipated heading back to Algiers in a day’s time. “Just received a report from the commandant of Cadets on Cadet Eisenhower [Ike’s son],” he noted. “You will be flattered.” The next day he congratulated Ike on his birthday and wished he could be there in person, but owing to complications involving “negotiations over strategic air forces and several other matters,” he would be delayed for several more days.84 He and Spaatz argued that the Fifteenth Air Force must remain under theater command. As Spaatz told Eisenhower, “Smith and I have okayed this plan.” Over the next days, their consistent opposition killed Arnold’s scheme for forming a unified air command.85

The other matters Smith alluded to involved future operations in Italy and the eastern Mediterranean. Smith passed on some bad news to Eisenhower. Production projections for landing craft proved far lower than expected. Eisenhower passed on Alexander’s assessment that “the removal of craft as ordered by the Combined Chiefs of Staff will seriously prejudice our operations to gain Rome.” Thirty-six landing craft/tanks were currently engaged in supply roles because of the extensive German destruction of infrastructure. Smith initially supported the idea of moving landing craft to Europe based on existing schedules. Eisenhower now wanted him to make the point that without sea lift, the Allied forces in Italy would be forced “into frontal attacks which will undoubtedly be strongly contested and prove costly.” Even if the ground attacks succeeded, AFHQ would not possess enough landing craft to sustain the advance. He deflected Smith from raising the question of the transfer of landing craft to the United Kingdom but directed him to argue for increased production.86

In between these ongoing discussions about air command and landing craft, Smith received an invitation to Hyde Park for a meeting with the president and Hopkins before he left. In typical Roosevelt style, the conversations covered a wide range of topics—primarily Overlord versus the Mediterranean. From their talks, Smith concluded that Roosevelt had made up his mind on Marshall’s going to Europe. The president now appeared “sold” on Eisenhower as army chief of staff.

As was always the case, Smith’s hectic schedule allowed little time for Nory. Since the end of August he had been worried about her. Nory’s aged mother’s health was failing. Torn between tending to her mother and carrying on her various volunteer works with the Gray Ladies at Walter Reed and acting as hostess at USO functions, Nory developed some health problems of her own. As Smith told a Washington friend, “Nory has been used to my carrying the load in cases of this kind and I dread to think of her having to do it alone.” As it turned out, Nory managed fine without Beetle. He found her recovered and busy.87

Eisenhower described Smith’s contributions as “a master of negotiations” as priceless.88 Aside from Smith’s dealing with the British and the associated and enemy powers, Eisenhower relied on his persuasiveness and his connections inside the CCS and the War Department, and especially with Marshall, for defending the theater’s prerogatives. Smith scored some successes. As he assured Eisenhower, “most of our recommendations will be approved.”89 Despite mounting pressure from the British to publish the text of the Italian surrender, Washington blocked its release and, in so doing, acknowledged support for Badoglio’s tottering government. Although the specifics of command relations never emerged, Smith and Spaatz defended the theater’s control over strategic air forces. He talked to the AGF command and expressed Eisenhower’s views on the proposed revisions in force structures. He got a hearing with Marshall on Patton and on promotions Eisenhower wanted pushed through. And he finally succeeded in firming up policy and arrangements for a military government in Italy—a vexing problem occupying much of his attention for months.

Not all his efforts achieved results. De Gaulle’s latest grab for power confirmed the president’s worst suspicions. To Roosevelt, de Gaulle remained a militarist, quasi-fascist, would-be dictator and a very dangerous man. The president had pulled out all his tricks to prop up Giraud, only now to recognize (but not acknowledge) he had backed the wrong horse. The unbendable de Gaulle might offer the only alternative—there was no other contestant—but Roosevelt steadfastly refused to concede anything but a military role to the general. AFHQ’s preference for de Gaulle did not go unnoticed by the president. Forewarned by McCloy, who knew only too well Roosevelt’s intransigence on the question and the price men paid for obstructing his will, Smith merely made soundings. As Hughes predicted, Smith exerted no discernible influence on anybody’s thinking on command billets in Overlord. Nor did he get any solution on the degree to which AFHQ would direct special operations in the theater. Smith would continue to arbitrate among contesting claimants—OSS, SOE, and the commanders in chief—for operations that assumed greater importance and calls on theater, mostly air, assets.90 And he failed to blunt criticisms of the theater’s handling of replacements.

Although it is difficult to gauge what influence he exerted, Smith made the case for continuing offensive ground operations in Italy to the combined and joint planners, OPD, Marshall, and the president. Throughout 1943 the Allies conducted campaigns in the Mediterranean without clearly defined political or grand strategic objectives. In the absence of guidance from above, the campaign in Italy lacked coherence from the start. AFHQ had already fulfilled the objectives assigned it by the CCS: Italy had been knocked out of the war, Naples and the Foggia airfields were secured, and German forces were tied down in Italy and the Balkans. The question now revolved around whether AFHQ should maintain offensive pressure in Italy. Ultra provided evidence in early October that the Germans intended to fight a defensive winter campaign south of Rome; the hardening German defenses already made that obvious. Pressed by the escalating bombing offensive against the Reich, and faced with an irretrievable disadvantage in the air over the Mediterranean, the Germans left only a token Luftwaffe presence in the theater. The Quadrant decision effectively turned the Mediterranean into a strategic backwater. Seven divisions would be withdrawn for Overlord, and a proposed invasion of southern France (Anvil) would subtract two more. Allied air and sea power granted potentially enormous operational flexibility, but the lack of landing craft and the Quebec timetable erected obvious impediments. Why not batten down; maintain enough pressure to compel the Germans to retain forces in Italy, the south of France, and the Balkans; conduct the bomber offensive from Foggia; and begin the process of moving earmarked divisions, air assets, and landing craft to England? To the extent any strategy existed, it seemed directed not at winning the campaign but simply at stretching it out and preventing any redeployment of German forces to France.

The answer rested in the irresistible tug of Rome. Marshall considered Sicily the crossroads of Allied strategy. Once taken, the road inevitably led to Rome. Churchill cautioned Alexander that “no one can measure the consequences” of failing to take the Eternal City. Smith talked up Eisenhower’s projection that Allied forces would hold the line at Leghorn-Florence-Rimini by spring 1944. He left Washington with no firm strategic guidelines but, more important, without receiving a shutdown order. AFHQ received the go-ahead to conduct offensive operations, albeit with diminishing assets, for the rest of the year.