Appendices

1. Chopsticks 183

2. Katsuobushi 185

3. The Kitchen and Its Utensils 187

4. Kombu 190

5. The Meal 193

6. Miso 196

7. Saké 198

8. Salt 200

9. Sansai 202

10. Soy Sauce 204

11. Sushi 206

12. Tea 208

13. The Tea Ceremony 210

14. Umami and Flavor 211

15. Vegetarianism 216

16. Wasabi 218

17. Wasanbon Sugar 219

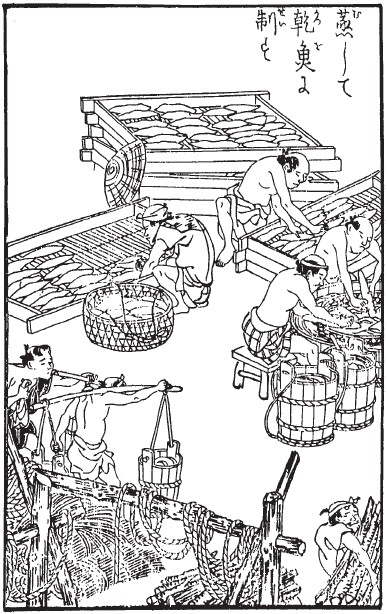

The above illustration, taken from Nihon sankai meisan zue, published in Osaka in 1799, shows the making of katsuobushi.

APPENDIX

Notes: Boldface indicates an entry in the Japanese-English section.

1 ❖ Chopsticks

The Japanese have not always eaten with chopsticks (hashi). Until the end of the eighth century the common people ate with their hands. The nobility had already started using chopsticks and spoon after the Chinese fashion, but the spoon was never taken up by the common people and by the tenth century had gone out of use among the nobility.

Compared with the flat-ended Chinese chopsticks, the Japanese ones are rather short. On average, Chinese chopsticks are 26 cm long, whereas the Japanese ones for home use are about 22 cm and the Korean ones even shorter at 19 cm. However, different kinds of chopsticks are used for different purposes and some of these are very short.

At home, chopsticks for eating are usually made of lacquered wood or bamboo, and superior ones are, or rather were, made of ivory. On special occasions such as New Year, high-quality plain wood disposable chopsticks are used, folded up in a piece of paper called hashi-gami. On such occasions a chopstick rest (hashioki) might be used, but many people don’t even possess chopstick rests, let alone use them.

In the kitchen, saibashi of various sizes are used for cooking and for other purposes, such as getting things out of bottles. Such chopsticks are extremely convenient.

Out-of-doors, waribashi are the rule. These are disposable chop-sticks and are made as a pair in one piece, prepared so as to be pulled apart into separate sticks at the time of use. It is quite obvious that they have never been used. They usually come in a little paper envelope called hashibukuro. Being disposable, they save restaurants a lot of washing up, but do seem to be rather wasteful. It is estimated that eight billion of them are used in a year. From the point of view of a foreigner not entirely at ease with chopsticks, waribashi are wretched. They always break apart the wrong way, sometimes so much so that you have the embarrassment of asking for another pair. And being much shorter than ordinary chopsticks, they are difficult for people with large hands to manage. The only way to avoid problems with waribashi is to carry your own chopsticks, a custom that might well be encouraged.

Prawns served in the shell, whether to save trouble or more likely because they are more decorative that way, cannot be peeled with chopsticks. A lot of people abandon them, but some brave souls revert to the ancient custom of eating with the fingers, or they peel them with their fingers and put them into their mouth with chop-sticks.

Chopsticks clearly determine the way food must be served. Food has to be served in pieces that are manageable, though the limits often seem to be stretched with furai, especially the very popular ebi furai, large prawns deep-fried in a coating of egg and bread crumbs, which might be big enough for about three mouthfuls.

Finally, chopsticks are the ultimate criterion of whether or not a food can be considered Japanese. If a food can neither be drunk from a bowl, nor eaten with chopsticks, then it is not considered Japanese. For example, pōku katsu (pork cutlet) is the same as tonkatsu, except that it is left in the piece and has to be eaten with knife and fork. It is therefore not Japanese. Neither is curry and rice (karē raisu), since it is eaten with a spoon.

2 ❖ Katsuobushi

Smoked, dried bonito (katsuobushi) is such an essential, everyday product that there is no general awareness of just how remarkable it is. It is for all the world like a moldy chunk of wood, and to prepare it for use it is actually shaved on the kitchen equivalent of a carpenter’s plane. In fact, the language of katsuobushi is the language of wood. Bushi means a lump or knot of wood and the best katsuobushi (in the piece) is referred to as hon kare bushi, kare meaning seasoned (of wood). The shavings are used to make the standard stock for soups and dips (dashi). Katsuobushi itself is quite unique to Japan, made by a complicated process, apparently without an equivalent anywhere else in the world, which was perfected about 1675 in the district of Kishu, southeast of Osaka. Prior to that, the bonito (katsuo) was simply dried, without the smoking and curing that the perfected process requires.

The process begins, of course, with the catching of the fish, which in itself is a remarkable feat. The fishermen are ranged fairly close to each other along the gunwales of the fishing boat, casting their lines with unbaited hook and landing their catches with a rapidity that has to be seen to be believed and a dexterity that miraculously keeps their neighbors from having their eyes fetched out. Most of the fish are brought in fresh either to Makurazaki, at the southeastern tip of Kyushu, or to Tosa, on the southern coast of Shikoku. It is in these two places that most katsuobushi is nowadays made.

As soon as the fish are landed, the unique process, which is beautifully shown in outline in a series of illustrations in Nihon sankai meisan zue, published in 1799, begins. (See p. 182.) First of all, the fish, which can weigh up to 4.5 kilograms, are filleted into two, and then the fillets from the larger fish are halved, a process known as namagiri. The fish is then simmered for twenty minutes to set the protein, which comprises 77% of the dry matter. This process is called nijuku. An hour later, the bones are removed with tweezers (hone nuki).

The smoking process (mizunuki baikan, meaning dry heating) is the next stage. For six or more hours a day everyday for up to two weeks, the fish is hot-smoked in a chamber with the smoke of various oaks, or sometimes wild cherry, beech, or chestnut. This process reduces the moisture content of the fish, which is now called arabushi, coarse fillets, from 70% to 25%. These are trimmed and put out in the sun for two or three days to dry and are called hadakabushi, naked fillets.

Next begins the long process of curing (kabizuke), which will remove the remaining moisture. The trays of hadakabushi are placed in a chamber impregnated with the mold Aspergillus glaucus. Long-established mold chambers have no need for the mold to be introduced, since it is already there in abundance. After two weeks, the fillets with the first growth of mold are removed from the chamber and placed out-of-doors for the sun to kill off the surface mold, a process known as hiboshi. The molding and sunning are repeated over a period of six weeks until the fillets become like completely dried-out chunks of wood. The sound given out when you tap one piece against another indicates the quality. The higher the note the better. Katsuobushi in this form will keep forever.

The fillets of katsuobushi must be shaved for use. Katsuobushi planes are identical with carpenter’s planes except that they are mounted upside-down on a box with a drawer for the shavings to drop into. The box with plane is called simply katsuobushi bako, literally katsuobushi box. Machines do the job commercially. It is the shavings (kezuribushi) that are used in cooking. Nowadays few households and only the best restaurants shave the katsuobushi in the traditional way, yet the katsuobushi bako is still sometimes given as a traditional wedding gift.

Unique as the making of katsuobushi is, the shavings are not something out of the ordinary. One way or another, they are necessary in the preparation of every Japanese meal. Ideally the shavings are made at the time of cooking, and it is said that high-class restaurants wait until the customer appears before shaving the katsuobushi for his soup stock. The best of the fragrance is very volatile and soon decreases. Shaving the katsuobushi on a plane at home used to be the norm, but nowadays most people buy bags of shavings at the supermarket. All that can be said for store-bought shavings is that they are convenient. The fragrance cannot compare with that of the freshly shaved shavings.

The best dashi is made by immersing katsuobushi shavings in boiling water for a short time and then straining off the liquid. When well made, this dashi (katsuodashi) has an incomparable aroma and goes particularly well with the sliver of citron peel (yuzu) in Japanese consomme (suimono). The dipping sauce for tempura (tentsuyu) is also based on stock made with katsuodashi.

Katsuobushi shavings are also used as a relish, for example, sprinkled on top of cold tofu. They provide sodium inosinate, a nucleotide that increases the umami (for which see also Appendix 14), that is to say, it boosts the flavor.

3 ❖ The Kitchen and Its Utensils

In Japanese advertisements for “mansions” (flats, apartments) the letters LDK, standing for Living, Dining, Kitchen, are often seen. Since LDK has an interesting connection with the traditional Japanese kitchen, I shall start by describing that room.

The Traditional Kitchen

The part of a traditional Japanese house set aside for cooking and eating, though considered to be one area, was in two parts. The first part, doma, was at ground level and indeed often simply had the beaten earth of the ground as floor. This was where the kamado stood, at which rice and miso soup were cooked. The nagashidai was also here, for cleaning vegetables and washing dishes and utensils, always in cold water. Cold water, considered purer than hot water, was sufficient, since nothing was greasy or oily. The windows did not let in a great deal of light, since they were fitted with vertical slats and horizontal shelves on which the cooking utensils were ranged. Smoke escaped as best it could without a flue.

The second part was adjacent to the doma, but at the raised level of the rest of the house. Though under the same section of the roof as the lower part, this was the living and dining area and contained the irori (centrally situated hearth), sunk in the middle of wooden flooring, where that was the custom. City houses did not have irori, nor was it customary in western Japan. Although the primary purpose of the irori was for heating, certain kinds of cooking, such as oyaki and kiri-tanpo, could be done there, and possibly even certain nabemono with the jizaikagi, a hook suspended from the rafters, on which to hang the pot. This hook was normally used for the kettle to heat water for tea. Above the irori was a shelf called hidana or hodana, which could be used for smoking food, since there was no flue. The smoke from the fire found its own way out, killing off unwanted mosquitoes and other insects in the process.

These two adjacent parts of the traditional kitchen were treated as a single living-dining-kitchen area, an early version of today’s LDK, which in turn leads us to the modern kitchen (daidokoro).

The Modern Kitchen

Whereas modern houses generally have a separate kitchen (still with shelves placed in the windows for storing utensils), in apartments the kitchen, dining, and living areas tend to overlap in the LDK pattern, thus continuing the layout of the traditional house. Although kitchens are provided with water heaters, some people still prefer to wash the dishes in cold water. Cooking is normally done on two gas rings, since ovens are not used in Japanese cooking, though nowadays microwave ovens are almost universal and sometimes also operate as regular ovens for cooking Western food, which is very popular. Many people love to bake cakes, cookies, and even bread. Frozen foods are slowly becoming more accepted and the microwave is useful for preparing these, as is also the popular oven toaster, in which, also, the toast for a Western-style breakfast, now more common than the traditional Japanese breakfast, can be made. The working area in the kitchen is always minimal.

The kamado, that important symbol of traditional family unity, has been replaced by the automatic rice cooker; the seirō (traditional wooden steamer) has been replaced by the mushiki (modern-style aluminum steamer) on the gas ring, and miso soup is also made on the gas ring. In other words, apart from the rice cooker, the traditional kamado and shichirin (brazier) have both been replaced by the gas konro. There are usually only two rings, an arrangement that is quite limiting for Western cookery, as is the cramped work space. People from Western countries usually find Japanese kitchens rather hard to adapt to.

Utensils

Pots, pans, plates, bowls, and ladles are much the same everywhere. But the Japanese kitchen has a number of utensils that are very interesting and quite unique. The following utensils are described in the Japanese-English section of the dictionary: dobin (teapot); hōchō (knife); hone nuki (fish-bone tweezers); ichimonji (scraper-spatula); kamado (kitchen range); katsuobushi bako (box for shaving katsuobushi); komebitsu (rice chest); koshiki (sieve); kyūsu (small teapot); makisu (mat for sushi); manaita (chopping board); menbō (rolling pin); nabe (pot, saucepan); nukiita (type of board); o-hitsu (container for serving rice); oroshigane (grater); otoshibuta (drop-lid); renge (Chinese spoon); saibashi (kitchen chopsticks); sasara (brush); shichirin (brazier); suihanki (automatic rice cooker); suribachi (mortar); surikogi (pestle); tamajakushi (ladle); tawashi (brush); teppan (hot plate); toishi (whetstone); zaru (colander).

Usu and kine (the large mortar and pestle) were not used in the kitchen, but in an area just outside the kitchen. Sometimes they were operated by foot-power.

The following are dining rather than kitchen equipment: chabudai (low table); jūbako (tiered food box); oshiki (dining tray); zen (individual low table).

Some of these utensils and pieces of equipment are not only useful but most unusual. The katsuobushi bako is quite unique to Japan. The whole idea of making stock with shavings of cured fish is imaginative, to say the least. Then to bring the carpenter’s plane into the kitchen to make the shavings can only increase the unusualness of this operation. The blade must be very sharp and very finely adjusted, or else the katsuobushi comes out as a powder.

The mortar and pestle known as suribachi and surikogi too are unusual and extremely useful, as anyone who has tried to bray sesame in a smooth-sided mortar will attest. This type of mortar and pestle could be useful in a kitchen anywhere, not just in Japan.

The oroshigane, especially in its domestic ceramic form, is just as useful for grating apple as it is for daikon. All shapes and sizes are available, and often both shape and glaze are very beautiful. The same can be said of pottery storage-jars (kame 并瓦, 甕) with their pattern of glaze dripping down from the rim.

Finally, the Japanese steamer (kaku seirō) is not only beautiful but very practical. Unfortunately it is also rather expensive and not easy to get hold of. (See also seirō.)

The traditional Japanese cooking utensils bring art and crafts-manship into the kitchen and comprise a unique and very practical batterie de cuisine.

4 ❖ Kombu

The Japanese are great eaters of seaweed. The coastal waters provide many different kinds in abundance. Seaweed is easily preserved by drying, is easily transported, has an indefinite shelf life, is highly nutritious, and can be prepared and served in many tasty ways.

“Tasty” is a very significant word, since it was in Japan that the importance of monosodium glutamate with regard to taste was discovered, researched, and promoted through the concept of umami. (See also Appendix 14.) Monosodium glutamate was discovered in the remains of some stock a scientist had accidentally boiled dry during his researches in flavor and nutrition. The stock was made of the seaweed known as kelp or tangle or kombu, konbu in Japanese and botanically known as Laminaria. There are more than ten species of kombu used for food in Japan, the commonest being Laminaria japonica. It is the best-known dietary source of iodine and a rich source of iron and other minerals as well as vitamin B1.

Kombu grows in the cold waters off the coast of northern Japan, mostly around the northern part of Hokkaido. If the water gets too warm for too long (longer than a couple of months at 20°C or more), the kombu dies. New growth is not from the stem, but from the tip of the leaf, and it is the second- or third-year growths that are harvested, since they are the best for food. Harvesting is done with long poles with forks or hooks at the end, from July to September. Specially constructed kombu boats take the harvesters out to the kombu beds. Only kombu harvested live from the sea is eaten, dead fronds washed up on the shore not being so flavorful.

Once brought to land by the boats, the kombu is spread out on the ground to dry in the sun. Nowadays the drying-off process is completed by hot-air fans in drying chambers. The kombu is then folded, made up into bundles, and sent to market.

The most basic form of kombu on the market is dashikonbu, fairly large pieces of blade kombu used for making stock. This kombu should not be washed but at most should only be wiped with a slightly damp cloth. This is because the flavor lies on the surface, which also means that the kombu should be left in the boiling water only for a short time, ten minutes or twelve at the most.

Although stock made from katsuobushi is much more fragrant than that made from kombu, kombu contributes greatly as a flavor enhancer because of the very high amount of natural monosodium glutamate it provides. It became important for stock making because of the Buddhist rejection of the eating of any kind of flesh. Thus, from early times Kyoto, the center of Buddhist vegetarianism, and its neighboring port Osaka became the main centers of kombu distribution and use. Kyoto cooking still places great emphasis on the use of kombu in many different ways.

Kombu appears in many guises. It starts off a dark brown-green color and when dried, of course, is even darker. Seaweed shops sell dried blades over a meter in length, but usually it is packaged in shorter pieces, the width normally being about 10 cm. Also sold are very small pieces for sucking (o-shaburi konbu, for which see also konbu).

Kombu is shaved in various ways, often after being soaked in vinegar and dried again. This is oboro konbu or tororo konbu. There is also kizami konbu, an aristocratic exotic product traditionally favored by imperial nuns. This, like other forms of kombu, is sometimes served deep-fried.

Another way of preparing kombu is to boil it with soy sauce in the preparation called tsukudani konbu. Cut into small squares, this is much used as tsumamimono to go with drinks.

Kombu suitably prepared is also used for rolling up various fillings such as sardines. The rolls can be served on their own or put with many other ingredients into the hot stock of a popular dish known as o-den, which is always served with very hot mustard.

Last but not least there is kombu tea (kobucha). Powdered kombu and sometimes other dried ingredients such as perilla (shiso) and Japanese apricot (ume), with a little salt, are mixed with boiling water and drunk as a kind of herb tea. It makes a tasty, nutritious, caffeine-free drink. Not surprisingly, the best of these teas come from Kyoto.

Kombu is said to be good for reducing high blood pressure, and many people drink the water in which a piece of the root end of a kombu blade has been soaked overnight as a medicine.

Finally, there is the ritual use of kombu. It forms part of the special New Year decorations in the home and is often used as a food gift to the gods in Shinto shrines.

5 ❖ The Meal

Meals vary according to the needs of the occasion, and appropriate styles develop. The main styles of meal in Japan are the family meal, the packed meal, and the formal meal.

The Family Meal

Ordinary people in Japan started using tables only in the second half of last century. Until then, individual settings of food were served on trays (oshiki) or trays with legs (zen) in front of each person on the floor. This custom has by no means died out and has at any rate ensured, in contrast to the Chinese custom, that food is normally served in individual portions. The main exceptions to this are communal one-pot dishes such as sukiyaki, cooked at table, and the special New Year o-sechi ryōri, which is packed in one set of boxes for all. At a family meal, all the dishes except those that really need to be eaten hot (rice and soup) are placed on the table beforehand, normally in individual portions. The main exception might be pickles. Since some people like to eat a lot of them and others don’t like them at all, it is more practical to have pickles on a communal plate. Few housewives spend the day considering the aesthetics of arranging three sardines on a plate as a professional chef might do, so the appearance of the food on the table is attractive rather than aesthetically captivating.

The menu is normally the basic ichijū sansai (a soup and three dishes), followed by (or with) rice, pickles, and tea. The three dishes are usually namasu (sashimi or vinegared raw fish), nimono (a gently simmered dish), and yakimono (a grilled dish). These three could be replaced by nabemono (a one-pot dish). Fresh fruit is often served right at the end of the meal with the tea.

The Packed Meal

The boxed meal (bentō) is an excellent and highly adaptable institution. Anything from a simple school lunch or a picnic or a lunch on the train to the haute cuisine of the shōkadō bentō or the somewhat less grand makunouchi bentō (originally designed for eating during the interval of a Kabuki performance) can be packed in a box and taken wherever it is needed. It doesn’t necessarily have to be taken anywhere. There are restaurants, especially in Kyoto, which specialize in bentō meals. In this case, all the food may not be contained in the box, which is but the centerpiece of an exquisite still life. Only hunger could prompt one to disturb the tastefully arranged morsels.

The overriding consideration in making a bentō is to have a variety of different-colored foods and to arrange them in an aesthetically pleasing way. There should be at least ten different items, though the shōjin ryōri vegetarian bentō sold on Kyoto Station Shinkansen platforms contains over twenty items. The rice can be served in a separate box that forms a nest of two boxes. Traditionally the rice is cold, but nowadays many bentō takeaway shops put piping-hot rice in at the last moment.

Formal Meals

Formal meals offer the area above all for intricate rules governing appearance, since it is here that appearance is the most important thing. Ka’ichi Tsuji, one of the great masters of high-class Japanese cuisine writes, “There is nothing more important in Japanese food than arranging it well, with special regard to the color, on plates chosen to suit the food” (辻嘉一 『四季の盛りつけ料理の色と形』). The absence of any reference to flavor is revealing. Donald Richie, in his highly recommended book A Taste of Japan, writes, “The food is to be looked at as well as eaten. The admiration to be elicited is more, or other, than gustatory. The appeal has its own satisfactions, and it may truly be said that in Japan the eyes are at least as large as the stomachs. Certainly the number of rules involving modes and methods of presentation indicate the importance of eye appeal.”

There are two main types of formal meal. Firstly, there is the meal that you would typically get at a wedding reception. Here, as much of the food as possible is laid on the table beforehand. Things like soup and hot savory custard are served during the meal. Sushi or sekihan (glutinous rice steamed with adzuki beans, a celebratory and most delicious dish) might be served at the end of the meal, not so much with the intention that the guests should eat it then and there, but that they should take it home.

The menu would be composed on the following basis: zensai (appetizers); suimono (clear soup); sashimi (raw fish); yakimono (grilled food); mushimono (steamed food); nimono (simmered food); age-mono (deep-fried food); sunomono (vinegared foods) or aemono (cooked salad).

The end of the meal is more variable, but as mentioned above, sekihan is likely to be served. Fresh fruit and tea will very likely also be served.

The second type of formal meal is known as kaiseki ryōri. (Ryōri means cookery, food, cuisine.) Actually there are two kinds of kaiseki, indicated by two different ways of writing the expression. The formal kind is designed to be served at a full tea ceremony and hence is called cha kaiseki. The other kaiseki tends to be a rather jovial drinking party.

In all the formal meals the diner is given no choice. The chef decides the menu, which he does according to strict and elaborate rules, the first of which is that the menu must highlight the season. Then plates and vessels must be chosen to suit the food. The basic rule is that round pieces of food should be placed on a square dish and square or long-shaped pieces of food must be put on a round dish. One needs a lot of dishes, since the pattern and color of the dish should also suit the season. The food is arranged on the dish according to the Japanese rules of moritsuke.

Of course, there are many other kinds of meal to suit different occasions. A traditional Japanese breakfast follows the basic pattern of rice, miso soup, pickles, and side dishes. Picnics, often with a widely varied menu, are also popular.

6 ❖ Miso

Miso is a fermented paste of grain and soybeans. It is not only a highly nutritious basic Japanese foodstuff, but also has many uses as a very savory flavoring. There are innumerable varieties, but the basic categories are rice miso, made from rice, soybeans, and salt; barley miso, made from barley, soybeans, and salt; and soybean miso, with only soybeans and salt. Western Japan favors barley miso and sweet rice miso; a fairly restricted area of central Japan favors soybean miso (hatchō miso); and the rest of the country, rather salty rice miso, which represents over 80% of the miso sold in Japan. Red miso (akamiso), which comprises about 75% of all rice miso, is red to brown in color and high in protein and salt. White miso (shiromiso), by contrast, is rather sweet. It is a famous product of Kyoto, expensive and regarded as high class. It is particularly useful in aemono and in sweets. There are also variety misos, usually eaten as a relish rather than used as an ingredient, and which are often quite sweet and contain vegetables as well as whole soybeans, or flavorings such as yuzu (Japanese citron) or mustard.

To make miso, rice or barley that has been steamed is allowed to cool almost to body temperature and is inoculated with spores of the Aspergillus oryzae mold and cultured for a couple of days. Then soybeans are washed, cooked, cooled, crushed, and mixed with the cultured rice or barley kōji along with salt and water. This mash is put into 2-m deep cedar vats and the slow process of fermentation begins. For the best miso this would see two summers, during which period bacteria and enzymes transform the grain and beans into a highly nutritious paste, deep in color and rich in aroma. It consists of about 14% high-quality protein and has a consistency similar to peanut butter. The color ranges from very dark brown to yellow, and the salt content ranges from 5% to 15%.

The early history of miso in Japan is not at all clear. Miso derives from the Chinese chiang and it could be that two different traditions, one coming via Korea and the other direct from China, have evolved the same product by slightly different methods. The arrival in Japan would have been during the sixth or seventh century. Before that, the Japanese used hishio, mainly fish products such as shiokara and uoshōyu, a fish sauce similar to those of Southeast Asia.

In the year 701, Emperor Mommu established a bureau to regulate the production, trade, and taxation of miso. By this time, Japanese miso had probably acquired its own character, quite distinct from the Chinese chiang of its origins, and by the end of the century different Chinese characters were being used to write the name. In the early days, miso was made by Buddhist monks at the temples and was consumed especially at the imperial court. However, by the middle of the tenth century, miso was no longer restricted to the capital, but was being made in the provinces, ready for the great food revolution that was brought about by the reformist warrior government of the Kamakura period (1185–1333). Until this time, Buddhist monks had largely catered to the effete aristocrats at the imperial court in Kyoto. Now they began to concern themselves with the spiritual needs of the common people and encouraged a simple, healthy life with two vegetarian meals a day. A simple meal consisting of rice (or barley, or millet for the really poor), pickled vegetables, and miso soup became the norm and has remained so ever since. The high nutritional value of miso has been a very important feature of the Japanese diet from that time on.

Thus, miso soup, which the Chinese had never made from their chiang, was a Japanese product of the Kamakura period. However, it was not until the Muromachi period (1333–1568), when the government returned to Kyoto from Kamakura, that miso as such became really popular, with various culinary uses developing quite apart from soup, and different varieties of miso becoming popular in different areas.

The main types of miso have been mentioned above. There are also many “variety” misos, perhaps the best known of which is kinzanji miso. Kinzanji miso differs from other miso in being made from a special kōji that contains both soybeans and whole-grain barley, traditionally in equal proportions. Nowadays, however, the proportion of barley is greatly increased to give a sweeter, more easily made product. A chunky texture results not only from the presence of the whole grains of barley but also from the soybeans, which are roasted and cracked. All sorts of vegetables and seasonings are added, including chopped eggplant, ginger, burdock, white pickling melon (shirouri), kombu, daikon, and cucumber. Shiso leaves and seeds, sanshō pepper, and tōgarashi pepper can be added for seasoning. The fermentation period lasts for six months, and the vegetables and seasonings may be added at the start or halfway through.

Kinzan-ji is the name of one of China’s five great Sung-dynasty Zen Buddhist temples, and it is thought by some that the prototype of kinzanji miso was brought to Japan from China in the middle of the thirteenth century. Misos of the kinzanji type are used as toppings for slices of crisp vegetables such as cucumber, or with rice or rice gruel, whereas regular miso is above all used for soup (miso shiru), in nimono and yakimono (dengaku), as a medium for pickling miso pickles (misozuke), and in many other ways.

7 ❖ Saké

Even in English, saké is the preferable name for Japanese rice “wine,” since the word wine is not really appropriate, though it is true that both saké and wine are products of yeast fermentation. In Japan saké is also called nihonshu 日本酒 (Japanese liquor) or sei shu 清酒 (pure liquor).

The wealth of variety of saké available throughout Japan is quite amazing, for not only do all the big saké breweries produce a wide range of sakés to be distributed nationally, but all over the country small local breweries produce their local saké (jizake).

The Brewing of Saké

The brewing of saké is quite a complicated process. Winter is the best time to make it, since, among other things, the cold affords better control over the fermentation. First of all, large-grain rice of high quality is chosen and polished. Polishing is a very variable factor, depending on the type of saké to be produced. In the best ginjōshu, the highest quality saké, only 30% of the grain may be left, but in lesser quality saké, only 30% of the grain may be removed. After polishing, the rice is washed and soaked for a short while and then steamed.

About one-quarter of the steamed rice is used for making kōji, being cooled to about 30°C for the purpose; the rest, to be used in the actual fermentation, is cooled to a much lower temperature, about 5°C. Making the kōji takes about thirty-five hours in a special room kept hot and humid to encourage the growth of the mold Aspergillus oryzae, which is sprinkled over the rice. Next, the kōji and yeast are mixed in a tank of water, and the rest of the steamed rice is added. The yeast multiplies and fermentation begins. This is now called the seed mash (moto). When the seed mash has matured, it is transferred to the fermentation tank, where fermentation continues for about three months, with kōji, water, and steamed rice being added at three intervals. During this period, the kōji converts the rice starch into sugars, and the yeast simultaneously starts the alcohol fermentation. This is what is called moromi (the main mash). When fermentation is complete, the moromi is pressed through cloth under high pressure and the residual lees (sakekasu) formed into blocks to be used for cooking and pickling. The slight cloudiness left in the saké is removed either by filtration or simply by allowing it to settle. The saké is then pasteurized at 60°C and stored in tanks to mature for several months. It is then blended and bottled.

Types of Saké

There are many different kinds of saké. Ginjōshu, the ultimate of the saké brewer’s art, has been mentioned above. It is expensive and hard to get, being made in very limited quantities. The very best never reaches the market.

Saké usually has rectified alcohol added, but there is no added alcohol in junmaishu (pure rice saké). It is consequently fairly heavy.

Honjōzukuri is a saké that has a rich, traditional flavor but at the same time has a much appreciated mildness. Added alcohol must not exceed 25% of the total alcohol. Ginjōshu is the top grade of honjōzukuri.

Nigorizake is cloudy because the cloth through which it is filtered is not tightly woven. It is similar to doburoku (illegal home-brewed saké) and may be unpasteurized, in which case it is “alive” and still fermenting.

Sweet and Dry

Saké ranges from bone dry to fairly sweet. Dry is karakuchi 辛ロ and sweet is amakuchi 甘口. There is an official scale of sweetness and dryness, the nihonshu do, running from -10 to +10. ±0 is neutral, +10 is quite dry, and -10 is quite sweet, but other factors, especially acidity, affect the individual perception of sweetness and dryness. The only way, ultimately, to find out about saké is to engage in some serious tasting.

8 ❖ Salt

There are no salt deposits anywhere in Japan so all salt (shio) has either to be taken from the sea or imported. The importation of salt, now on a considerable scale for industrial use, is a comparatively recent development, and in the not too distant past, all salt used in Japan was extracted from the sea locally. All ordinary table salt still is. It is one of the ironies of marketing that many people seek out the more expensive salt labeled sea salt, apparently unaware that such specialty salt is more likely to contain added non-sea salt from foreign salt deposits.

Japan is too humid for natural solar evaporation in salt pans to be effective, and considerable effort and ingenuity are required to extract this basic essential from sea water. From the earliest times until about the sixth century and even later, seaweed was burnt and brine was made from the ashes. This brine was then evaporated by boiling until salt crystals formed. It wasn’t until the Edo period (from the beginning of the seventeenth century) that much more effective methods of salt extraction were invented, and a huge, bustling industry, covering extensive tracts of Japan’s coastline and lasting until the early 1970s, developed, especially round the coast of the Inland Sea. Here big differences in sea level between high tide and low tide enabled the flooding of tidal sand terraces to provide a more concentrated brine for further evaporation by boiling in pans until the salt crystallized out. Recently there has been a surge of interest in the salt terraces (enden), and Shikoku has seen a small resurgence of the type of salt terrace which superseded the tidal terrace. In this kind of salt bed the sea water is first concentrated on a sloping sand terrace, then the resulting brine is cascaded down vertical evaporation racks, with the wind assisting in evaporation. However, to help the process along, salt imported from the huge salt beds of the Western Australian desert is added nowadays at the first stage of concentration.

In other parts of Japan the work was much more laborious because buckets of sea water had to be carried to sand terraces above the tidal line. This is still done at Suzu, on the Noto Peninsula, kept going as a registered Intangible Cultural Property, and the salt thus made is available in small quantities.

Since 1972 the Japanese have extracted salt from the sea by the ion-exchange system, a process of electrolysis. The salt terraces have all but disappeared and so has the old-fashioned kind of salt that contained nigari (bittern), the traditional coagulant used in making bean curd. It has not disappeared entirely, however, for the old-style salt is necessary for making the pyramid-shaped bricks of salt set before the gods. The Grand Shrine of Ise, Japan’s premier Shinto shrine, has its own private salt terrace, mi-shio hama, where salt for the ritual uses of the shrine is still made in the traditional way. Bean curd, which was traditionally curdled with nigari, is now mostly curdled with chemicals.

Salt is not much used at table in Japan. It is sometimes used with tempura and other deep-fried foods, as well as with yakitori. Yet there is no lack of salt in the ordinary Japanese meal. Far from it. There has traditionally been too much. Miso and soy sauce, both common ingredients in Japanese cooking, contain a lot of salt, and pickles, appearing at every meal, require a lot of salt in the making. Salt is also a common seasoning in cooking, often in combination with monosodium glutamate, which in any case occurs naturally in so many foods. Shioyaki, an excellent method of grilling fish, uses lots of salt on the fish, especially on the fins and tail, to avoid charring.

Finally, two of salt’s most ancient uses in Japan are the ritual ones of purification and protecting from evil. These are seen at Shinto shrines and in the liberal scattering of salt during bouts of sumo. Little piles of salt (morijio) are also sometimes placed at the entrance of bars in the entertainment districts. This practice derives from an ancient Chinese custom of proprietors’ putting little piles of salt outside their establishments to induce carriage oxen to stop there and lick it.

9 ❖ Sansai

The following is a list of the commonest plants used in sansai ryōri. The most important ones have an asterisk, referring to an entry in the Japanese-English section of the dictionary:

akaza あかざ 藜 goose foot, lamb’s quarters Chenopodium album var. centrorubrum

asatsuki* あさつき 浅葱 asatsuki chive Allium ledebourianum

ashitaba あしたば 明日葉 angelica Angelica keiskei

fukinotō* ふきのとう 蕗の薹 unopened bud of Japanese butterbur Petasites japonicus

gyōja ninniku ぎょうじゃにんにく 行者葫 a kind of chive Allium victorialis var. platyphyllum

itadori* いたどり 虎杖 Japanese knotweed, flowering bamboo Polygonum cuspidatum

junsai* じゅんさい 蓴菜 water shield Brasenia schreberi

kanzō かんぞう 甘草 licorice Glycyrrhiza uralensis

katakuri* かたくり 片栗 dog’s tooth violet Erythronium japonicum

kogomi こごみ 屈み fiddlehead of the ostrich fern kusasotetsu

kusasotetsu くさそてつ 草蘇鉄 ostrich fern Matteuccia struthiopteris. Also called kogomi こごみ 屈み. The young fronds are fiddleheads.

momijigasa もみじがさ 紅葉笠 a kind of Indian plantain Parasenecio delphiniifolia (formerly Cacalia delphiniifolia). Closely related to yobusumasō.

nemagaritake ねまがりたけ 根曲がり竹 Chishima sasa Sasa kurilensis. Also called chishimazasa ちしまざさ 千島笹

nobiru* のびる 野蒜 red garlic Allium gravi

ōbagibōshi おうばぎぼうし 大葉擬宝珠 plantain lily Hosta sieboldiana

okahijiki おかひじき 陸鹿尾菜 saltwort Salsola komarovii

sasa* ささ 笹 bamboo grass Sasa spp. See also nemagaritake.

seri* せり 芹 water dropwort Oenanthe javanica

shiode しおで 牛尾菜 green brier, cat brier Smilax riparia

taranome たらのめ 楤芽 shoot of the angelica tree Aralia elata

tsukushi* つくし 土筆 spore-bearing shoot of field horsetail, sugina (Equisetum arvense)

ukogi うこぎ 五加 Acanthopanax gracilistylus

uwabamisō うわばみそう 蟒草 Elatostema umbellatum var. majus Family Urticaceae (which contains strawberry nettle and stinging nettle)

warabi* わらび 蕨 bracken Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum

[yama] udo* [やま]うど [山]独活 (wild) udo Aralia cordata

yobusumasō よぶすまそう 夜衾草 a kind of India plantain Parasenecio hastata subsp. orientalis (formerly Cacalia hastata subsp. orientalis). Closely related to momijigasa.

yomena よめな 嫁菜 a species of aster Aster yomena (Kalimeris yomena)

yomogi* よもぎ 蓬 wormwood, mugwort Artemisia princeps

zenmai* ぜんまい 紫萁、 薇 Osmund fern, royal fern Osmunda japonica

10 ❖ Soy Sauce

Originally, Japan’s basic condiment was uoshōyu, a salty liquid made from rotting fish. Such sauces are still very much in use in Southeast Asia, but Buddhism, introduced to Japan from China, brought with it Chinese vegetarianism and a range of basic foods and condiments based on the soybean. Tofu, miso, and soy sauce are originally from China. So the fish-based uoshōyu was replaced with the soybean-based shōyu, and the Japanese developed such a highly refined product that no other soy sauce is good enough to substitute for it.

The early history of soy sauce in Japan is not particularly clear, but soy sauce seems to be connected with the liquid that separates from hishio and miso during their fermentation. This liquid was called tamari, a word with quite a different meaning from that in current usage, which means soy sauce made without wheat. This very early version of tamari is now called tamari shōyu. The earliest reference to it seems to be A.D. 775, and somewhat more clearly in the thirteenth century, but the word shōyu doesn’t seem to have come into use until the late fifteenth century at the earliest and wasn’t really established as the name for the sauce until 1643, when the half-wheat, half-soybean product that we know today was developed.

The traditional process of making soy sauce is as follows: grains of whole wheat are parched and cracked and soybeans are steamed. These are then mixed with spores of the mold Aspergillus oryzae and incubated for three days, making the kōji. This kōji is added to a brine solution, the result, now called moromi, being put into huge cedar casks holding up to two thousand gallons and left to mature for at least two summers. When ready, the moromi is pressed in cotton sacks under heavy weight, a process that extracts crude soy oil as well as soy sauce. The oil rises to the surface and is removed. The soy sauce is pasteurized and bottled. The best quality takes two years to make.

This basic process produces six different types of soy sauce:

1. Koikuchi shōyu, heavy soy, is made as above. It is the standard soy sauce, made of 50% soybeans, 50% wheat. If you are going to keep only one kind of soy sauce, this is the one to buy.

2. Usukuchi shōyu, thin soy, is used in cooking and is somewhat saltier than koikuchi shōyu. The lighter color mainly results from the higher salt content and a shorter period of maturation.

3. Tamari is, or should be, soy sauce made without wheat. Because tamari goes so well with sashimi, other soy for sashimi is often improperly given this name. Reading the legally required label in Japanese on the back of the bottle can reveal if you are being deceived.

4. Saishikomi shōyu is twice-processed soy. For this soy sauce, the kōji is mixed not with brine but with shōyu and the rest of the traditional process repeated. The product is strong and is especially used with sashimi and sushi. It is often improperly called tamari.

5. Shiro shōyu, meaning white soy, is a light honey color and has indeed a slightly sweet flavor. The wheat content is much higher than that in the other soys. Shiro shōyu should be used as soon as possible after being made since it gradually darkens, though the taste does not change. It is used a lot in high-class cookery, especially for such dishes as sunomono, and has a particularly attractive flavor. Unfortunately it is not available abroad.

6. Kanro shōyu is a superior kind of traditional soy made only in the city of Yanai in Yamaguchi Prefecture. It is top-quality, hand-made saishikomi shōyu with slightly less salt, less amami (sweetness), but more umami seibun. (See also Appendix 14.)

Because the traditional process of making soy sauce takes such a long time, short cuts and quicker processes have been devised, some with atrocious results, some not too bad, but none that can in any way produce soy sauce comparable with the traditionally made product, which now, unfortunately, accounts for less than 1% of soy-sauce production.

11 ❖ Sushi

Sushi is not only one of the best-loved dishes in Japan, but is also extremely popular in many places abroad. It began as a way of preserving fish. This ancient kind of sushi, known as narezushi, is not unique to Japan, but is also found in many countries of Southeast Asia. It is not the only feature Japan has in common with those countries, for uoshōyu, the forerunner of soy sauce, still made in parts of Japan, has its counterparts in those same countries. The nam pla of Thailand is famous.

In Japan the best-known narezushi is the funazushi of the Lake Biwa area near Kyoto. After the six months or so it takes to mature, the fish is eaten and the rice thrown away, but in contrast with modern sushi, it is not a particularly popular taste.

There are many kinds of sushi, all of them based on sushi rice, which is rice that has been carefully prepared with slightly sweetened vinegar. Sushi vinegar (sushizu) is available in bottles. The preparation of good sushi rice takes great skill and experience.

The most highly regarded and no doubt most expensive kind of sushi is nigirizushi, also called edomaezushi. Edo was the premodern name of Tokyo, and it was there that nigirizushi originated and flourished for a long time before spreading to other parts of Japan. Nigirizushi consists of a little fistful of sushi rice on top of which some wasabi is smeared. On top of this a slice of raw fish or other seafood is placed. Octopus and prawns are cooked, squid is not. Omelet is also used and so are both salmon roe (ikura) and sea urchin (uni). These latter two are kept in place by a strip of nori around the rice. Nori is also used to hold blanched daikon sprouts (kaiware) in place. Among the favorite sushi toppings are toro, ebi, shako, anago, ika, tamagoyaki, and many kinds of raw shellfish. Nigirizushi is eaten, preferably in one mouthful, after the topping is dipped in soy sauce.

Osaka’s contribution to the sushi scene is oshizushi. Sushi rice and seafood, mostly cooked, are pressed in a rectangular box and then cut into slices. Osaka is especially famous for its battera, a pressed sushi of mackerel. Kyoto is also famous for its mackerel sushi (saba no bōzushi, for which see also sabazushi), which, however, is not pressed but shaped in a makisu. The top quality (but only the top) can be very good indeed.

The makisu, which is a mat made of long thin slivers of bamboo for rolling things up, is also and mainly used for making makizushi. Makizushi is a great standby for almost every occasion, and is not expensive, since a minimum of fish is used, or none at all. Quite thin types of makizushi may have just a cucumber filling (kappamaki) or tuna (tekkamaki). Great fat ones are stuffed with kanpyō, mitsuba, kōyadōfu, mushrooms, and omelet, and their very lavishness makes them look inviting. The filling is rolled up in a sheet of nori.

Gunkanmaki is a kind of nigirizushi in which a topping of ikura or uni is prevented from falling off by a strip of nori around the sides.

With chirashizushi, sometimes called barazushi, both meaning “scattered,” or gomokuzushi, literally five-item sushi, the topping is scattered (usually quite artfully) on top of a bed of sushi rice. The color combination is important to make the dish look attractive, so there is usually a sprinkling of denbu to add a splash of red. Shredded omelet contributes yellow, and green may well appear in the form of green peas. Chopsticks are needed to eat chirashizushi.

Last but not least of the well-known sushis is inarizushi. Inari is the fox god, who loves to eat abura-age (thin, deep-fried slices of tofu), and inarizushi is made by stuffing pockets of sweetened abura-age with sushi rice. It is very luscious and moist.

All over Japan there are numerous local varieties of sushi, including such interesting ones as sugatazushi, in which a fish is stuffed with sushi rice, sliced, and served in its original shape. This is particularly done with mackerel (saba) and sweetfish (ayu).

Sushi has an image of delight and gratification among the Japanese. It is great party and picnic food. Nigirizushi can be eaten not only in the pleasant atmosphere of a sushi shop, washed down with quantities of green tea, but when the need arises at home to feed unexpected guests, home delivery can be arranged by telephone, and the guests will feel grateful and honored.

12 ❖ Tea

The earliest mention of tea drinking in Japan is A.D. 815, when tea was served to the emperor. This was powdered green tea (matcha) and it wasn’t until the late sixteenth century that leaf tea, the type known as sencha, was imported from China. Leaf tea was easier to make than matcha and cheaper, so it became popular. The drinking of powdered tea, which the priests used to keep themselves awake for prayer vigils because it has a high caffeine content, was institutionalized as the tea ceremony. (See also Appendix 13.)

Many kinds of leaf tea are drunk in Japan. The Japanese term for tea is cha, and the unfermented leaves normally drunk (called green tea, though it is sometimes brown) are referred to with the honorific o-, thus o-cha. This distinguishes it from kōcha, the fermented kind of tea drunk in the West, which is also fairly popular in Japan. Kōcha is inaccurately translated as black tea, the common English term for the fermented teas usually drunk in the West, even though kōcha literally means red tea. To avoid misunderstanding in English, o-cha is best translated as green tea, and kōcha as tea. Kōcha is an imported product, whereas o-cha is locally grown, especially near Kyoto and in Shizuoka.

The top grade of green tea is gyokuro, which is very expensive and savored in small quantities. Very young buds of old tea bushes specially protected from the sun are used, and the tea is brewed at quite a low temperature, 50°C, in a small teapot known as kyūsu.

The middle grade of o-cha is sencha. Carefully picked young, tender leaves are used for this tea, which is brewed in a kyūsu and drunk in small quantities to savor rather than quench the thirst. The water should be 80°C and the tea should be steeped for one minute. Sencha is not a breakfast tea but a tea to serve to guests. There is a sencha ceremony, but it has never been so widely practiced as the matcha ceremony.

The everyday tea is bancha. This is the tea to drink at breakfast, the tea to quench one’s thirst. It is coarse and full of twigs and is made from older leaves than the other varieties. It is made with boiling water and its flavor is considerably improved if the tea is parched, in which case it is called hōjicha. When brewed, hōjicha is more or less the color of fermented teas and has a slightly smoky flavor that comes very close to teas drunk in the West. People drink it right up to bedtime as it seems to have less caffeine than other teas. It is quite delightful when made with plenty of leaves.

Genmaicha is another kind of bancha that is very good and aromatic. Grains of rice (genmai) that are roasted until they pop are added to this tea. It too is made with boiling water and has a slightly nutty flavor.

There are many other “teas” not made from the tea plant Camellia sinensis. Kombu seaweed gives kobucha, which often has the addition of umeboshi and shiso. Infusions of shiitake and matsu-take, bought as powders, are delicious, and mugicha, infused from parched barley (mugi) and chilled, is the essential cool drink for summer. Many other twigs and leaves, such as persimmon leaves, are dried and infused for their medicinal properties. They are bought at the pharmacy rather than from the tea merchant.

Last but not least, there is cherry-blossom tea (sakurayu), an infusion of salt-pickled cherry blossoms. This is drunk on happy occasions, such as weddings, because of the auspicious imagery of the cherry blossom.

13 ❖ The Tea Ceremony

The tea ceremony, chanoyu (literally tea’s hot water), was brought to Japan as a Buddhist ritual by the Japanese priest Eisai (1141–1215), who had learned about it in China while he was studying Buddhism there. He also brought back seeds of the tea plant.

From its earliest days, the ceremony was associated with Zen Buddhism and was practiced as one of the Zen “ways,” as those disciplines are called. In this context it was the “way of tea” (sadō or chadō). The great Zen monk Ikkyu (1394–1484) thought that tea produced greater enlightenment than long meditation. And indeed the very high caffeine content of powdered green tea (matcha) was certainly taken advantage of to keep the monks from dozing off during religious exercises.

The tea ceremony is still an important practice in Zen temples. However, it needs neither temples nor priests, so it often seems to the unenlightened observer purely social. It certainly has an established place in Japanese society as a social activity. No doubt this is connected with the fact that Zen is more a mystical philosophy than a religion, and in any case the link with Zen can be weak. A fuller account of the tea ceremony is given in Kodansha’s Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia.

The meal served at a full-scale tea ceremony (chaji 茶事) has an important place in the sphere of Japanese food. This meal (cha kaiseki) has had a surprisingly great influence on the West as inspiration for nouvelle cuisine and cuisine minceur. Apart from chaji there is a greatly simplified version called chakai 茶会 (tea party), when no meal is provided, merely tea made from the powdered green-tea leaves. Some kind of sweetmeat (wagashi), usually higashi, is served beforehand.

Although there is a tea ceremony of sencha, normally tea ceremony refers to the service of powdered green tea (matcha or hikicha 挽き茶, 碾き茶). Before the green tea is drunk, sweetmeats, wagashi of some kind, often higashi, are always eaten to counteract the bitterness of the tea.

14 ❖ Umami and Flavor

Flavor is a complex perception, drawing together the senses of taste and smell, as well as mouth feel, which is the basic element of texture.

There are several striking and very appealing aromas or smells for which Japanese food is notable. Above all, they are associated with soups. The following ingredients—katsuobushi, yuzu, matsutake, and miso—produce some of the aromas or smells unique to Japanese food.

When katsuobushi, which is dried, smoked, and cured bonito, and a basic of the Japanese cuisine, is freshly shaved and made into stock, it gives off an intriguing, unforgettable, and highly complex aroma that is clearly related to the smoking, drying, and curing of fish. It is not a marine or fishy smell, but one in which oak smoke predominates.

Yuzu is the Japanese citron. For the most part, only the peel is used, as an aromatic (suikuchi), especially in clear soups, the stock for which would be made with katsuobushi and kelp (konbu). Clear soups are served in lidded bowls, which means that the delicate citrus aroma of the yuzu is concentrated under the lid and bursts forth in a stimulating way when the lid is removed.

Matsutake (Tricholoma matsutake, formerly Armillaria edodes) is a fungus with a striking phallic shape that is the cause of much ribaldry. These fungi grow in pine woods and are difficult to find. In the market they are very expensive. In Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, Shizuo Tsuji writes of them: “Scented with the fragrance of piney woods, these mushrooms that grow only in the wild in undisturbed stands of red pine are so highly prized that they tend to be used as the main ingredient or the primary focus of a dish.” The aroma of matsutake is incomparable and is perhaps best appreciated in the Kyoto specialty called dobinmushi, in which matsutake is served in very delicate stock in little individual teapots. The aroma is held in the pot and bursts forth when the lid is lifted.

When the fermented-soybean paste known as miso is made into a soup with either katsuobushi or dried-sardine stock, it gives off a strongly savory, appetizing aroma highly reminiscent of roasting meat. This meaty savoriness is typical of fermented-soybean products and is to be attributed to the high quality and quantity of protein-forming amino acids that they contain.

Whereas yuzu and matsutake are known almost exclusively for their aromas, katsuobushi and miso, besides their characteristic smells, also have equally appealing tastes. Both are rich in what is called umami seibun, the “tastiness” factor, which is considered, above all in Japan, to be one of the primary tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami.

Western science has traditionally identified four basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, with appropriate taste receptors on different parts of the tongue, though the discreteness of the different receptors has now come into question. The Far East, on the other hand, has traditionally favored the notion of five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and hot (pepper hot). These five have been referred to in Chinese literature from at least the third century B.C. However, in present-day Japan, the fifth one, hot, has been replaced by umami, which, it is argued, is one of the basic tastes, with its own taste receptors on the tongue. According to Japanese thinking hot joins “metallic” and “astringent” as one of the three tastes that stimulate the mucous membranes of the mouth as well as the taste buds.

Umami seibun (the tastiness factor) is identified quite specifically with certain amino acids and nucleotides, namely monosodium glutamate (MSG), sodium inosinate, and sodium guanylate. There is no question that, on the one hand, these three are important flavor enhancers and, on the other, have a powerful synergistic effect on each other, up to eight or nine times the properties of the single ingredients. What is hotly disputed, at least outside of Japan, is whether umami constitutes a basic taste. Opposing the concept of umami as a basic taste would mean opposing the Ajinomoto company, one of the world’s largest and most powerful food companies. That company was founded to market monosodium glutamate, which the company called Ajinomoto, “the foundation of taste.” The controversy is largely over theory. The practical details concerning these amino acids and nucleotides are, however, important and useful.

Monosodium glutamate is naturally present in many foods, but above all in kelp (konbu) and Parmesan cheese. Green tea is pretty high in monosodium glutamate and so is fresh tomato juice and many other foods. The list is seemingly endless.

Sodium inosinate is above all found in katsuobushi and in the little dried sardines (niboshi) that are used with kelp to make dashi stock. Since there is an eight or ninefold enhancement of flavor when these two are used together, it is obvious why stock made in this way should be so effective as the basis of soups, sauces, and dips. This combination also turns up very effectively in Worcestershire sauce and its Japanese derivatives. All this was discovered and put into practice long before anyone knew anything about amino acids.

Sodium guanylate is especially abundant in dried shiitake mushrooms, so it is reasonable, in the light of current knowledge, for vegetarians to use dried shiitake instead of katsuobushi for making stock. This is exactly what Buddhist vegetarians have traditionally done. Guanylate is found primarily in mushrooms, but there is also a little in beef, pork, and chicken.

In recent years there has been considerable controversy over the use of monosodium glutamate as a food additive, with the problem of the so-called Chinese-restaurant syndrome. The problem is not clear-cut, and there are many factors to consider. Monosodium glutamate as an additive is not a natural derivative of kelp, but is made from sugar-beet molasses or glucose by a process of bacterial fermentation. Whether this is significant is hard to know. At any rate, it is not a “natural” product. An important question is whether there are people who suffer from the monosodium glutamate that occurs naturally in so many foods. Such people would not only have to avoid Japanese soups and stocks, but also such things as soy sauce, which has its own naturally occurring monosodium glutamate.

Perhaps the important factor is the amount of the additive used. It seems clear that many Chinese chefs, especially at cheaper restaurants, are very heavy-handed with their MSG. It is interesting that no one ever complains about a Japanese-restaurant syndrome. Certain it is that an enormous amount of MSG is used in Japan. As well as restaurant chefs, many housewives wouldn’t be without it. There are many products available in which an appropriate amount of MSG is combined with salt. The presence of salt effectively prevents one from overdoing the MSG. The Ajinomoto company even markets a superior combination, in which sodium inosinate is added in the correct amount for the full synergistic effect with the glutamate. The main ingredient, of course, is salt. If you are going to use these additives, this is certainly the best way to do so.

Whether glutamate, inosinate, and guanylate, as the “umami factor,” comprise the fifth basic taste, or whether they should be considered primarily as flavor enhancers, is a theoretical question. The fact is that they do behave as very effective flavor enhancers when used in small amounts and correct proportions.

As for the other tastes, salt and sugar as sweetness par excellence are used as flavor enhancers in Japanese cuisine. Salt, apart from anything else, is essential to the human body. The Japanese diet used to be far too salty, but of late the role of salt as a flavor enhancer has been encroached on by sugar to the extent that virtually all prepared foods sold in supermarkets and convenience stores have at least a little sugar in them, often a lot.

Sour is not a big taste factor in Japanese cuisine, and salt pickles are far more widespread than vinegar pickles. Japanese rice vinegar, as the representative of sour, is very delicate, the best of all being that made from unpolished glutinous rice (genmai mochigome su). Sweetened vinegar is used very effectively as a light dressing for such vegetables as cucumber.

Bitter is a very restricted taste anywhere in the world, since it is not a taste humans take to naturally and is generally associated with medicine. In Japan the traditionally eaten guts of some fish and shellfish have a certain bitterness, but in general there is a strong tendency to shun the bitter taste. Such foreign things as bitter chocolate and bitter lemon soft drink have never become popular in Japan, yet other bitter drinks such as beer, whisky, and coffee have all become extremely popular. Chocolate in Japan is another example of the general tendency to sweetness, and avoidance of the bitter, with plain (bitter) chocolate not being at all popular and milk chocolate being far sweeter than would be usual in Western countries.

Japanese food has a reputation for being rather bland, yet despite “pepper” hot not being a major taste factor, it certainly has an important place. Wasabi, which is very pungent, is very highly regarded. It is mixed into the dip for sashimi, is an essential ingredient of nigirizushi, and has many other uses. Chili pepper is the major ingredient of the seven-spice mixture called shichimi tōgarashi, tōgarashi being the Japanese word for chili pepper. This mixture is sprinkled on noodles and various other dishes. Then there is sanshō, Japanese pepper, the seedpods of the prickly ash. It is also used in the seven-spice mixture. Curry too, as served in the popular karē raisu, can sometimes be hot.

As for the “metallic” and “astringent” tastes, they are not really a factor in food.

15 ❖ Vegetarianism

Vegetarianism in Japan is almost completely an aspect of Zen Buddhism, which seems to observe the Buddhist strictures against eating fish, fowl, or flesh (“sentient” creatures) more strictly than other groups. Secular vegetarianism exists, but even the largest cities have little to offer in the way of vegetarian restaurants. Moreover, and perhaps surprisingly, it is not easy to select a completely vegetarian meal at an ordinary Japanese restaurant. Certain Zen temples, however, serve vegetarian food of the most elaborate and delicious kind, and sometimes in the shadow of such temples, non-temple vegetarian restaurants provide the same kind of food.

Shōjin Ryōri

Buddhist vegetarian cuisine is known as shōjin ryōri, and was brought to Japan by the monks who introduced Buddhism in the sixth century. Shōjin ryōri spread considerably in the thirteenth century, with the arrival of Zen. The most obvious feature is the use of soybean products instead of fish and meat. Soybeans are even used, along with shiitake mushrooms and konbu, in making dashi. Tofu, miso, shōyu (soy sauce) are all great standbys. In Kyoto yuba (soy-milk skin) is added to the list, as well as fu (wheat gluten). Great importance is given to gomadōfu, made of sesame and kuzu. It is a very nutritious food and if carefully made by hand, quite ambrosial to eat.

It is a characteristic of Japanese shōjin ryōri that the food should not emulate non-vegetarian dishes but be presented for what it is without disguise. There are no “tofu steaks.”

The best introduction to shōjin ryōri must surely be to eat at one of the many yudōfu restaurants surrounding Nanzen-ji, a great Zen temple in Kyoto. Chosho-in is one of them and is actually a charming old temple, quite small, with a beautiful Japanese garden. A platform juts out into the carp-filled pond, and to sit there with a little brazier (shichirin) eating yudōfu on a calm, sunny day in autumn, especially when the maple and ginkgo leaves are just turning color, is quite enchanting. And memories of Kyoto’s shōjin food can be prolonged with a shōjin bentō bought on the Shinkansen platform at Kyoto Station. It contains over twenty different food items.

Fucha Ryōri

When the great Chinese Zen patriarch Ingen, who gave his name to ingenmame (kidney beans), brought his own particular sect of Zen to Japan, he built Manpuku-ji, a temple with a very Chinese-style monastery at Uji, just outside of Kyoto and very famous for its growing of tea. He came to Japan in 1654, and the name of his sect is Obaku shū 黄檗宗. Obaku is now also the name of the district within Uji where the temple is.

The Obaku sect’s vegetarianism is very Chinese in style, and is called fucha ryōri. In fucha ryōri, the number of people must be four, or a multiple of four. Two diners face another two diners across the table and eat from common dishes with four portions arranged on them. The basis of the menu is two soups and six dishes of different types (nijū rokusai 二汁六菜). There is a serious attempt at making the food look like the forbidden meats and fish. The names of the dishes reflect this and are still Chinese, but over the years one Chinese feature of the food has been adapted to Japanese taste, for it is not so oily now as it originally was. Apart from at the main temple of Obaku Manpuku-ji, this food may be eaten in several temples in Kyoto. Kanga-an, a small convent in Kuramaguchi-dori, is especially charming.

Fucha ryōri is the vegetarian version of shippoku ryōri 卓祇料理, a Chinese style of cooking that came to Nagasaki at the beginning of the Edo period and included the flesh of wild animals, birds, and fish.

Caution: Vegetarian visitors on a budget should be aware that temple vegetarian food does not come cheaply. Serving it is a great source of monastery revenue. The meals are no more expensive than a similar level of meal would be in the secular world, but for a real treat at an affordable level, the shōjin bentō mentioned previously is the perfect answer.

16 ❖ Wasabi

Fresh wasabi, Wasabia japonica, the real thing, though grown in Taiwan and New Zealand on a small scale, is scarcely available outside of Japan, though it is sometimes exported frozen. Even in Japan, it is an expensive luxury. What is widely available is a green powder which, when mixed with water, is made up into a paste that goes under the name of wasabi, a cheap substitute in fact. The best wasabi, wild wasabi, grows high in the mountains in cool, clear, shaded, shallow streams of spring water. It is also planted on the banks of such streams and is cultivated in fields, especially in temporary vinyl greenhouses built on rice fields idle between the seasons.

All of the plant is used as food. The root, green in color, is grated and mixed with the soy-sauce dip for sashimi. Grated wasabi is also put between the rice and the fish of nigirizushi. Several kinds of grater are used for grating wasabi. The best kind, used by professionals, is made of the skin of angel shark (Squatina nebulosa), korozame in Japanese, glued onto a piece of wood. However, these are rather expensive, since the sharkskin wears out quickly, so a grater of tinned copper is often used instead. Domestic wasabi graters are pottery, metal, or plastic. They have a flat surface with raised teeth but no holes. Wasabi should be grated from the top of the root (near the leaf stalks) downward.

Because fresh wasabi is expensive, its presence is a good indicator of the better class of sushi shop or restaurant. Though pretty “hot,” it is not so harsh as white horseradish, a fellow member of the Family Cruciferae. Fresh wasabi does not retain its freshness very long and should be used up promptly. Only a small amount is dried and made into a powder. The powdered version, mixed with water and made up into a paste like mustard, is “Western” horseradish, Armoracia rusticana, with green coloring and some mustard powder added. Tubes of prepared wasabi are available and may contain both fresh wasabi and the made-up powder, or may consist entirely of either one. The one made of wasabi only is about twice as expensive as the others, and has a much shorter “use by” date. Outside of Japan, the wasabi in tubes is the best choice. An opened tube should be kept in the refrigerator and used up quickly.

An excellent pickle (wasabizuke) is made with wasabi, and the leaves of the attractive plant are made into a very refreshing vinegar pickle (suzuke) and are used in other ways in cooking.

Wasabi seems to lend itself to a considerable amount of commercial deception, possibly because horseradish is called seiyōwasabi (Western wasabi) or wasabi daikon (wasabi radish). The Japanese are reasonably aware of this, but abroad the true nature of the product often appears only on the label in Japanese, and many people think they are eating wasabi when actually they are eating colored horseradish.

17 ❖ Wasanbon Sugar

Wasanbon is a very rare kind of sugar, also called wasanbon tō, since tō means sugar in Japanese. It is made by hand according to a two-hundred-year-old traditional method, in Tokushima Prefecture, near Kochi Prefecture, on the island of Shikoku.

On the northern border of Tokushima Prefecture, an unusual kind of sugar cane, Saccharum sinense, Chinese sugar cane, is grown. In Japanese it is called take kibi or chiku sha. It is quite thin, being less than half the thickness of ordinary sugar cane, Saccharum officinarum. It is harvested in December and January, and the sugar production begins in the middle of December.

First, the cane is crushed to extract the juice, which is boiled until a lot of the water has evaporated and it reaches the “soft ball” degree. The resulting syrup is cooled and poured into pots to set. It is now called shirashita tō, consisting of crystallized sugar and invert syrup (molasses, treacle).

A lengthy process now begins, the purpose of which is to remove every trace of the treacle. It is in this process that techniques not used elsewhere are employed. Only about a third of the shirashita tō is sugar, treacle comprising the other two-thirds.

To extract the treacle, the shirashita tō is wrapped in cloth and placed in a pressing box that is operated by means of levers and heavy stones tied to ropes. This is followed by togi, literally “washing,” which is actually a process of hand-kneading with water for two hours. Traditionally the pressing and washing were done three times, hence the name sanbon, san meaning three. Nowadays it is actually done four times, the sugar getting cleaner all the time as more and more treacle is removed. It is believed that the thoroughness of this process is the reason for the softness and fineness of this sugar. When the pressings and wash-kneadings are finished, the sugar is laid out in trays for a week’s drying. Altogether the process takes twenty days.

The product is an extremely fine sugar that has a very important place in the making of top-quality higashi, a candy-like confection used in the tea ceremony. The top-grade makers, mostly in Kyoto, which is famous for higashi, say they cannot use any other sugar.

Higashi consist of a mixture of rice flour and fine sugar pressed into decorative molds and colored to suit the design. Their appearance can be very attractive, whereas their flavor is simply the flavor of raw rice flour and sugar. Since the flavor of wasanbon is so smooth and its sweetness so delicate, it is easy to understand what an advantage these qualities give to the higashi made from it. In any case, higashi are very convenient for drinking matcha (tea-ceremony tea) to sweeten the mouth in readiness for the bitterness of the powdered green tea, since most of them keep forever and can be permanently on hand for whenever needed.