Benchmarking is the systematic comparison of organisational processes and performances based on predefined indicators. The objective of benchmarking is to find the gap between the best practices and the present performance of the organisation in order to create new standards and/or improve processes.

There are five basic types of benchmarking:

All types of benchmark can be helpful: they give an organisation an insight into its strengths and weaknesses; they are objective; they uncover problems and indicate possible improvements; and they point out norms, new guidelines and fresh ideas to improve an organisation’s performance.

Different methods for benchmarking vary to the extent that they include situational characteristics and/or explanatory factors to account for differences between organisations (Figure 18.1). Moreover, some benchmarking methods include prospective trends and developments of best practices, or other practical issues that may arise in an industry.

The use of benchmarking depends on the goal. Bearing in mind the difference between intention and action, we can define the objective of benchmarking as the provision of an answer to any one of the following questions:

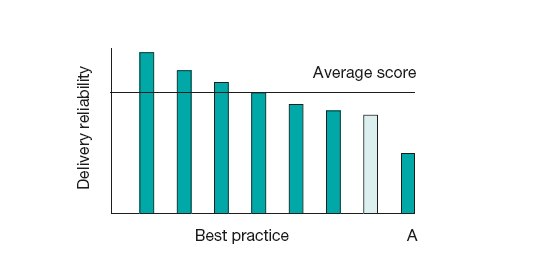

Usually, benchmarking is about comparing the organisation against the average of the benchmark population. This gives companies an insight into their own situation and into how the organisation performs compared with the average. Often, however, it is even more ambitious for the organisation to compare itself not against the average but against the best, or, for example, the top 25 per cent. By coupling this comparison to certain good or best practices, it often becomes very clear in which areas improvement actions are relevant.

The scope of a benchmarking project is determined by: the impact it may have on the organisation; the degree to which the results can be communicated freely, in order to increase the success rate of corresponding improvement projects; and the level of effort required to achieve results that are valuable in practice.

However, benchmarking does not lead to answers regarding how to improve, and it usually can’t give declarations of differences in performance, but rather gives insights into what to improve. Benchmarks offer no judgment and only when there is no explanation for a deviation does it make sense to look for improvements (e.g. relatively high training costs can be the result of a certain strategic choice that has to do with investing in employee skills).

Benchmarking juxtaposes existing information. Good benchmarking is often trickier than it appears at first sight. First, there should be very clear and unambiguous definitions. Then, measurement methods that objectively and properly measure what the organisation wants to compare are to be defined. When measuring at the organisation itself is already difficult, measuring at other organisations is likely to be even more so, if not impossible. Besides, organisations in general are often reluctant to disclose information to a competitor, even when the outcomes of the benchmark are made available to all participants. So many organisations make use of (independent) benchmark databases.

Next, the organisations (or peers) that are being used in benchmarking should be selected. Ideally they would perform better than, or at least equally as well as, the target organisation (or peers), as this brings most lessons to improve the organisation. In general, peers are identified via industry experts and publications. However, differences in products, processes, structure or the type of leadership and management style make it difficult to make direct comparisons between organisations. It is possible to overcome this difficulty in a practical way. Assumptions about the performance of the target firm can be made more accurate by benchmarking the indicator (e.g. ‘delivery reliability’) according to a number of explanatory factors. It is possible to compare organisations in cross-section for some indicators, based on explanatory factors. Reliable delivery of a product, for instance, depends on the complexity of the product. Therefore, a group of firms that have a similar level of product complexity will have similar indicators and will be a suitable peer group for benchmarking reliable delivery performance (see Figure 18.2).

After carrying out the benchmark, reporting on comparative performance per participant is done and improvement directions for deviations are defined per participant.

Figure 18.2 Example of benchmarking: (a) selecting a peer group; (b) finding best practice

Benchmarking is not straightforward. Too often, semi-committed managers or consultants perform benchmarking without the use of predetermined measurements or the proper tools for detailed analysis and presentation. Undoubtedly, many benchmarking projects end in dismay; an exercise often justifiably portrayed as being as futile as comparing apples and pears. Even when performed in a structured way, the ‘we are different to them’ syndrome prevents benchmarking from leading to changes for the better. Furthermore, competitive sensitivity can stifle the free flow of information, even inside an organisation.

By applying explanatory factors, benchmarking can not only provide comparative data that may prompt management to improve performance (indeed, it highlights improvement opportunities), but it also indicates original, but proven, solutions to apparently difficult problems. We therefore argue that it is precisely the differences between the firms in the peer group that should be encouraged, rather than trying to exclude organisations because of so-called ‘non-comparable’ products or processes.

A word of warning however: becoming as good as the benchmark (i.e. the average of the benchmark-population) should never be a goal in itself: no organisation will beat competition by being only equally as good!

Watson, G.H. (1993) Strategic Benchmarking: How to Rate your Company’s Performance against the World’s Best. New York: John Wiley & Sons.