Man may rise to the contemplation of the divine through the senses.

—Abbot Suger

“As the third year that followed the year one thousand drew near,” wrote medieval chronicler Raoul Glauber, “there was to be seen over almost all the earth, but especially Italy and France, a great renewal of church buildings. It was as if the world had shaken itself, and, casting off the old garments, had dressed itself again in every part in a white robe of churches.”1

One of those white-robed churches was in Sens, a town southeast of Paris on the river Yvonne, which had grown rich with the revival of the wool trade in the former Roman province of Gaul, or France. In 1130, its archbishop laid the foundations for a new cathedral, something larger and more splendid than its Romanesque predecessor. Ten years later, construction was still under way. When bishops, abbots, prelates, and other church officials arrived in the spring of 1140, they had to step over piles of masonry and dodge ropes from cranes as they assembled in the cathedral’s new choir. They were there for a church council, the most important in France ever. In terms of the history of Western civilization, perhaps the most important of all.

The Sens council had been summoned to hear Peter Abelard defend his strange new doctrines. His judges included a monk in his early fifties who was a particular friend of Sens’s archbishop and the acknowledged leader of Europe’s most dynamic new monastic order, the Cistercians. He was Bernard of Clairvaux, later to be canonized as Saint Bernard.

Under his leadership, the Cistercians had grown from a handful of monasteries to more than 350 houses by 1140. Although he was ten years younger than Abelard, Bernard was already the single most influential churchman of the age. He was an intimate adviser and friend to one pope, Innocent II, and the mentor and teacher of another, Eugenius III. Bernard was determined to cleanse from the Church all forms of corruption, including intellectual corruption. That meant a return to first principles, especially those of Saint Augustine, that “from this hell on earth there is no escape except through the grace of the Savior Christ, our Lord and God.”2 Bernard had heard a great deal about Abelard’s teachings. He didn’t like what he had heard.

“[Abelard] casts what is holy before dogs,” was how Saint Bernard put it in a letter, “and pearls before swine.”3 Sic et Non and Abelard’s other works “run riot with a whole crop of sacrileges.” Bernard was especially offended by how Abelard had held the Church’s great authorities up to logical scrutiny, criticizing their conflicting views on the Trinity and the Incarnation as if they had been ignorant students instead of divinely inspired Fathers and Doctors of the Church.

“The garments of Christ are being divided,” Bernard raged, “the sacraments of the Church torn to shreds.” Abelard “corrupts the integrity of the faith … and oversteps the landmarks placed by our Fathers” in the name of reason. A new gospel was being forged and a new faith being founded, the great Cistercian argued: a faith based on Aristotle. “Outwardly, [Abelard] dresses as a monk but inwardly he is a heretic.”4

Thus far, Abelard had been allowed to get away with his defiance, Bernard told Pope Innocent, “there being no David to defy him.” That is, until that summer of 1140, when at the church council at Sens they would finally meet. “Where all have fled before him,” Bernard wrote with a wry smile, “he calls me out … to single intellectual combat.” However, Bernard would be ready. “With the Lord to aid me, I have no fear of the worst man can do.”5

The square outside Sens’s cathedral was jammed.6 People had come to see the twin combatants clash like jousting knights in a tournament. The carnival-like atmosphere continued inside, where dozens of churchmen and dignitaries gathered under the soaring ribbed stone vaults and arches. Even King Louis VII was present. Everyone wanted to witness the headline bout between Aristotle’s most outspoken champion and the stern warrior for the faith of Saint Augustine.

Abelard was on his feet almost at once, ready for battle. The archbishop, however, insisted that the charges against him be read first. Disgruntled, Abelard sat down while Bernard, in a low, clear voice, began reading aloud the nineteen heretical propositions that authorities said were in Abelard’s writings.

“Number 3: That the Holy Spirit is the World-Soul. Number 4: That Christ did not assume flesh to liberate us from the devil.” As Bernard read, Abelard became more and more agitated. When Bernard got to the fifth accusation, that he had denied the Trinity, Abelard had reached his limit.

“He refused to listen and walked out,” Bernard remembered later. Abelard said he would appeal any decision by the Sens council, even though he himself had chosen his judges, “which,” Bernard noted with some asperity, “I did not think was permissible.”7 The much publicized match was over before it began. The crowd, including the king, was disappointed. Bernard, however, could be satisfied. He had faced his most dangerous adversary, and his adversary had retreated without a fight. The Sens council duly denounced Sic et Non and Abelard’s other works, and a furious but defeated Abelard was forced to throw his own books in the fire. Now it was up to Bernard to consolidate his victory not just over Abelard, but over the entire Aristotelian worldview.

What had offended Bernard most was how Abelard had tried to use the ancient pagan philosopher to pry open the most delicate divine mysteries. “He trie[d] to explore with his reason what the devout mind grasps at once with a vigorous faith.” The prophet Jeremiah had said, Unless you believe, you shall not understand. But Abelard, “apparently holding God suspect, will not believe anything until he has first examined it with his reason.” Philosophy had no business trying to lift the veil from mysteries beyond human understanding. The way to get to those, Bernard affirmed, was not through the mind but through the heart.8

From the point of view of Plato—not to mention Socrates—this was a shocking downgrading of reason. But Bernard was only following Plato’s hierarchy of knowledge as adopted and adapted by Saint Augustine. Just as reason is superior to opinion (doxa), so Saint Augustine taught that faith is superior to reason because it rests on the highest wisdom of all, the truth of God’s revelation.9 Faith of this potent kind is more than belief. When we say, “I believe the Pittsburgh Steelers will win the Super Bowl,” or, “I believe the person who stole my car will get caught,” we are talking about probabilities—or indulging in wishful thinking. Real faith is a matter of an unqualified emotional commitment, what Saint Augustine called love, or caritas: a fierce spiritual force that binds man to God and (as proved by the sacrifice of the Crucifixion) vice versa. “Faith avails not,” Bernard wrote, “unless it is actuated by love.” Love for Bernard was the gift of the Holy Spirit. It was the heartfelt token of salvation.10

To modern scholars, Saint Bernard does not strike a very sympathetic figure. They have tagged him as a puritan bigot who mercilessly hounded Abelard (“perpetual silence should be imposed on that man,” he urged one of the cardinals in Rome, “whose mouth overflows with curses, calumny, and deceit”) in the name of a narrow-minded Catholic orthodoxy.11 He fought hard to keep women out of the Cistercian order; he believed females to be sexual temptresses by their nature. It was one of the few battles he lost.12

All the same, it was Saint Bernard who put the image of the Virgin Mary, the nurturing Mother of God, at the center of the Catholic faith and who made the loving human heart the key to exploring religious truth—even the key to discovering God.13 Even more than Augustine, he is the first great religious psychologist—therapist, almost. Bernard’s goal was to lay bare the deepest recesses of the soul and bring man to a spiritual simplicity and humility. Looking forward, his theology prefigures the teachings of the most tenderhearted of medieval saints, Saint Francis of Assisi. Looking backward, Bernard’s goal was that of Augustine and, at one remove, Plotinus: the self-sacrificing, unwavering love that raises knowledge of ourselves to a mystical union with God.

This, Bernard decided, had been Abelard’s problem. He knew all about his rival’s dealings with Héloïse and deeply disapproved. But he also sensed that they sprang from the same pride that Abelard took in his own reason. Abelard’s love for Héloïse was actually a form of self-love, even self-obsession. “He is a man who does not know his limitations,” Bernard confided to a friend. “Nothing in heaven or on earth is hidden from him, except himself.”

It was a shrewd observation. For Saint Bernard, self-love is the root of all evil, and the Achilles’ heel of the Aristotelian mind. Not only does it block us from grasping the true nature of love, and hence of God. It also prevents us from realizing the relative unimportance of human reason.14

Without faith, Bernard affirmed, intellectual inquiry is doomed to run off the track. Worldly wisdom, he liked to point out, teaches only vanity.15 By contrast, by making God the center of our lives instead of ourselves, we are spiritually transformed. Through love of God, “he who by his former life and conscience was doomed as a true son of perdition to the eternal flames,” he wrote, “draws new life and hope beyond all expectation.” He is “rescued from a most deep and dark pit of horrible ignorance, and plunged into a pleasant region bright with eternal light.”16

Later, this spiritual transformation will be called being born again. It is in fact a Christian variant on Plato’s Myth of the Cave. “Once I was blind,” as the hymn says, “but now I see.” It was Saint Bernard’s goal to turn the Catholic Church into an instrument to enable people to see the world and themselves in the true light of God; in the phrase of William Blake, who shares a good deal with Saint Bernard, to see not with but thro’ the eye. Bernard wanted to draw people out of the cave and into the light of God, not by imposing new rules and regulations (although Bernard had no problem with those), but by appealing to human beings’ most basic feelings.

One way was through sermons. Saint Bernard transformed the art of sermons and elevated their importance in the medieval Church by introducing a rich evocative Latin style that appealed to listeners’ senses and touched their hearts. For those without Latin, Bernard saw the importance of using religious imagery like the cross, and figures like the Virgin Mary, as a way to speak directly to the emotional needs of the listener, even the simplest and least educated. The cross was the only decoration he allowed in his monasteries, as the symbol of God’s willing sacrifice of His only son to save humanity: a sacrifice born of true undying love. “Let no one who loves God doubt that God loves him”—and the sign of the cross is the proof of that promise.17

He also made the Virgin Mary a powerful symbol of the Church’s role as loving mother and intercessor with God. Thanks to Saint Bernard, the anonymous The Miracles of the Virgin became one of the most popular books of the Middle Ages. One new church after another would be dedicated to her, including two of the most famous: Notre Dame in Paris and Notre Dame in Chartres. Meanwhile, religious painters and sculptors of the age turned to depicting the tender scene of Virgin and Child as a way to reflect the compassionate face of Bernardine Christianity. They succeeded in establishing a genre that would reach its climax in the Renaissance and the paintings of Botticelli and Raphael—all due to the influence of the supposedly misogynist Bernard.18

Then there was music. Plato had always been aware of the power of music to stir human emotions, both for good and for ill. Pythagoras had also made Plato and the Academy aware of how music expressed the same divine order of number and proportion as in geometry. Plotinus had passed this Platonic fascination with music and number to Saint Augustine, who saw both as reflections of a divine order catastrophically disrupted by Adam’s Fall.19

Augustine then passed that same fascination to Saint Bernard and his followers. For the Middle Ages, music seemed to offer a new series of proofs of the existence of God, uncovered not through logic, but intuitively through the senses. Oddly, the medieval followers of Neoplatonism saw another of the liberal arts, astronomy, the same way. The phrase they coined for the coordinated precision of the heavenly bodies was “the music of the spheres.” No one in the Middle Ages actually hears the music of the spheres. But they could see and feel it as they watched the starry night move overhead month by month, season by season.

“Music,” Augustine wrote, “is the science of moving well.”20 Likewise, music was more than just a pleasing sound to Bernard. It was the divinely proportioned audible trace of God’s presence. Bernard was more involved in the creation of liturgical music than any Church Father since the creator of the Gregorian chant, Pope Gregory the Great. Bernard was convinced that the bliss of heaven itself was an eternal concert conducted by choirs of singing angels.21

Of course, any notion of perfect proportion must also have a visual component. And to see it requires something that Bernard believed also opened the heart to a knowledge of God beyond reason and logic. This was light.

Augustine and his Neoplatonist mentors had said that the light of nature was a reflection of God’s own radiance. It was what made the world intelligible to reason, “the divine illumination of the mind,” and had deep significance in the theology of Saint Bernard. But the Middle Ages owed its deepest debt for the importance of light in the Neoplatonist universe to an obscure Syrian monk who had lived centuries before—and to a shocking case of forged identity.

Shocking, because the perpetrator managed to escape detection for nearly one thousand years. Only Peter Abelard came close to guessing the truth. Even today, monks at the remote monastery at Mount Athos in Greece celebrate every October 3 as the forger’s feast day. Amid clouds of incense and the glow of oil lamps, they chant hymns of praise in front of his icon and recite his works aloud in order to understand the divine secrets of the universe.22

To them, he is still St. Dionysius the Areopagite, the first bishop of Athens, who had been converted by Saint Paul himself. To scholars, however, he is the Pseudo-Dionysius, one of the cleverest fakes of the late Roman Empire and without a doubt the most influential.

Who was he, really? No one has a clue. It is possible he bore the same first name as the man mentioned in Acts 17:34: “Certain men came to believe [Paul the Apostle] and came to him, among them Dionysius the Areopagite.” All his works were penned under that name. Yet all the evidence suggests he lived at least four hundred years later. Some suspect he was a Syrian, but no one knows for certain. He was certainly a monk, one heavily immersed in the Eastern traditions of Neoplatonism with its ideal of monastic life (passed down by a fourth-century admirer of Origen named Evagrius) as a single-minded contemplation of the divine.

Maybe he thought the pen name Dionysius the Areopagite would give his startling synthesis of Christian and Neoplatonist ideas more authority and credibility. He may even have believed that his words really were the kind of grand vision Saint Paul and the other early apostles had shared but never bothered to write down.23

Whatever his motivation, working day by day, year after year, quietly in his cell, the Pseudo-Dionysius wrote some of the most compelling and evocative treatises on theology ever written and fobbed them off as works by Saint Paul’s most famous disciple. Even after his act of forgery was discovered, his insights proved too valuable to be discarded. In fact, no one who enters a church today or visits a museum, no one who gazes at a landscape or buys a picture to hang on his living room wall, is entirely free from the influence of the Syrian monk and the startling new twist he gave to Plato’s influence on Western thought.

The Pseudo-Dionysius begins with a seeming paradox. We see God nowhere, and yet God is everywhere. The skeptic and atheist get stuck at the first obvious truth; they fail to push on to the second. The secret is that God’s presence is made visible to us not directly but symbolically, in a material world that bears the faint but still perceptible trace of a higher intelligible and spiritual realm.

The Pseudo-Dionysius’s God makes His impression on matter as (to borrow a metaphor from the author’s later admirers) a signet ring presses into a blob of hot wax. The signet lifts away and moves on; only the wax seal is left. Yet the impression that gives the seal shape and meaning still carries the trace of its original maker. That trace is a symbol, not because it stands for another thing, but because it is that thing in a different form—just as the world reveals God’s handiwork in a material form rather than His (and Plato’s) immaterial Forms.

In fact, at the deepest level of contemplation, the Neoplatonist Dionysius argues that we will no longer see the wax seal at all. Instead, what contemplation of the material world finally reveals to us is what made the impression in the first place: the hand of God Himself.24

Of course, moving from looking at a wax seal to looking at God is not so simple. As any good Neoplatonist knew, God’s presence in the world proceeds downward through a series of spiritual emanations, from the realm beyond Being and Non-Being to the perfect and intelligible, to finally the material and imperfect. Likewise, man’s knowledge proceeds upward along the same track, the Great Chain of Being.*

What the Pseudo-Dionysius did in his cell was work out the entire map of the universe of spirit in detail, from the top all the way down. He laid out the Great Chain of Being in an exquisitely defined series of gradations for which he coined a new term, the Celestial Hierarchy.

Like the Jacob’s Ladder in the Bible, Dionysius’s Celestial Hierarchy is a spiritual elevator that human beings can catch going both up and down. The hierarchy runs down by regular stages from God through His angels to intelligible realms like the Forms; then through the rational soul to the world of material bodies, including our own. It also carries us upward by the same gradations toward a mystical union with God, drawing us irresistibly stage by stage toward the One. “The aim of hierarchy is the greatest possible assimilation to and union with God … to become like Him, so far as is permitted, by contemplating intently His most Divine Beauty.”25

However, we can never get to that final mystical union entirely by ourselves. Our consciousness must be coaxed along, drawn in a great procession stage by stage from matter to mind to spirit, by the mediating presence of higher beings like angels, who bear the impression of God’s truth more immediately than we do.

Once we start the journey in earnest, Dionysius pointed out, we realize that the world around us is not some darkened cave devoid of meaning, as followers of Plato liked to claim.26 It offers a rich pageant of sights and sounds, a forest of symbols that constantly trigger new insights and urge us along toward a higher reality. And “every divine [movement] of radiance from the Father, while constantly flowing bounteously to us, fills us anew with a unifying power, recalling us to things above, and leading us to the unity of the Shepherding Father and to the Divine One.”27

The most important mediating force for the Pseudo-Dionysius was the Church. To the Syrian monk, the clergy, the liturgy, the sacraments, and even the Bible itself were nothing more than symbols to coax and guide us to that highest knowledge, the knowledge of God Himself. However, his more potent point was that everything in life is a mediating power to one degree or another. Nothing is entirely devoid of God’s spiritual beauty: “As the true Word says, all things are beautiful.” Indeed, without the presence of material things, especially beautiful things, the mind will never get started on its upward spiritual journey.

What opens the door for the journey and makes it possible? The answer is light: nothing more or less than the radiance of God’s presence in the world. Neoplatonists had always been fascinated by Plato’s remark in the Republic that the Good in Itself was the source of all light in the material realm.28 The Pseudo-Dionysius made creation of the visible world itself an act of illumination. His followers pointed out that we would not exist without light. In their eyes, all men are “lights” in that their existence bears witness to that one unifying Divine Light bathing them in the same penetrating radiance. In the final analysis, it is the presence of physical light that God uses to draw His creation toward Him—but above all, man.29

The Pseudo-Dionysius’s works were a triumph of the Neoplatonist imagination. In an age of science like our own, they seem wildly fanciful. The lists of seraphim, cherubim, thrones, powers, and the other grades of angelic beings seem like an elaborate fantasy game. However, in an age of faith like the early Middle Ages, with monastic imaginations starved for new stimuli, they were a stunning revelation. The first Latin translation of Celestial Hierarchy appeared at the court of Charles the Bald. It quickly became a Christian classic, along with the learned commentary provided by its Irish translator.† Readers were compulsively fascinated by the book’s elaborate angelology, but also by its budding theology of light. This struck a deep harmonious chord with followers of Saint Augustine, including Saint Bernard.30

All the same, the Pseudo-Dionysius’s promise of a knowledge of God achieved through the senses rather than the mind and reason found its most lasting home in the realm of stone rather than words and parchment. It is still visible today in the Gothic churches at Saint Denis and at Chartres.

In a purely technical sense, Sens Cathedral is probably the first Gothic church. When Abelard and Bernard met there in the spring of 1140, they probably did not notice that an architectural revolution was taking place over their heads. Its builders pioneered many of the characteristic elements of the Gothic style, from ribbed interior vaults and a three-part elevation, to the famous pointed Gothic arch for its windows.31

The pointed arch came from the East, from Islamic builders. Its rival the standard semicircular arch was the product of Aristotelian and Roman engineering. The pointed arch, by contrast, is the product of Platonic geometry. It results from the intersection of two arcs drawn on the same straight line—for French builders like the ones who built Sens and Saint Denis, essentially two quick swipes of a compass. Any builder worth his pay could then use a set of calipers to reproduce a series of those same arcs within the regular rectangle of the church’s outside wall, or crisscross a pair of pointed vaults inside a series of perfect squares in the interior, enabling him to prop up the roof with far less stress than the old barrel vault of the Romans.

In truth, a good master mason could build an entire Gothic cathedral with just a compass and a T square, a device he borrowed from Greek mathematicians for lining up perfect vertical and horizontal lines. This dazzling command of practical geometry made the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages truly independent businessmen. By the fourteenth century, they were already calling themselves free masons.‡ Some would claim their knowledge reached back to the Pyramids. In fact, the Pyramids employed a far cruder geometry than the Gothic cathedrals.32 The latter’s real designers were Plato and Pythagoras, via Euclid and Boethius. And certainly no Freemason would have been allowed near a church site if his practical geometry had not measured up to the sacred geometry of the twelfth century’s Platonic revival.

The man most active in bringing together these twin forces for divine order and proportion was Abbot Suger, head of the famous abbey of Saint Denis near Paris. Saint Denis had been the burial place of French kings since the early sixth century. It was one of the historic treasures of France. Although he had been tonsured and trained as a monk, Suger was more politician than churchman. He had served as the king’s ambassador at the papal court and handled secular affairs for his boyhood friend Louis VI for years.

Then, beginning in the 1130s, he launched a thoroughgoing reform of the Saint Denis abbey inspired by Saint Bernard’s Cistercian principles.33 With his single-minded drive and energy, Suger also supervised the rebuilding of the abbey church. The result was a startling new approach to church design both inside and out. Later ages would call it the Gothic. Suger himself called it simply “the new style” or, more precisely, “the style of continuous light.”

Once again, Saint Bernard was his inspiration. The great reformer had bitterly criticized the kind of twisting sculptural forms and garbled ornamentation that cluttered up Romanesque churches. He wanted his Cistercian abbeys to be as clean and pure to the eye as they were for the spirit. “There must be no decoration,” he said, “only proportion.”34

There were to be no painted frescoes or floor mosaics, no elaborate hangings. Instead, everything would reveal a clear geometric simplicity, using pure forms (the square, cube, rectangle, and that most potently Pythagorean of all geometric figures, the pentagon) to emphasize the principle of harmonious proportion. Suger would do the same with his plan for Saint Denis.

Its floor plan closely resembles the geometric simplicity of Bernard’s Cistercian churches.35 Painting and figurative sculpture disappeared from the church’s interior. The human figures carved on the outside, especially around and above the church’s entrance or portal, achieved a new monumental stillness, which is also strongly present in the west portal at Chartres.36 The Gothic sculptor and mason concentrated on cutting stone with clean precise lines and blank smooth surfaces. As for Saint Denis’s interior, it reveals a harmonious structure built entirely around bare walls and open bays. If architecture is frozen music, then Saint Denis is a visual hymn to divine perfection.§

The Neoplatonist theology of light was crucial for Suger. Here patriotic reasons played their part as well. In French, Saint Dionysius was Saint Denis. Since the first bishop of Paris and founder of the abbey c. 300 had been named Denis, it was all too easy to believe he had been the same Dionysius who had been Saint Paul’s disciple, as well as the author of the Celestial Hierarchy. In fact, Abelard’s problems with the monks at Saint Denis began when he dared to cast doubt on this triple misidentification. How likely was it, he pointed out, that a Latin-speaking saint living in France would write his most important theological tracts in Greek?37

The monks were outraged and drove Abelard out of the abbey. The assertion that the Celestial Hierarchy had been written by a Frenchman and the founder of Saint Denis became a matter of national dogma, one might almost say national theology. “Among ecclesiastical writers” in France, enthused one late-twelfth-century author, “Dionysius is believed to hold the first rank after the Apostles.”38 Abbot Suger turned his church into a radiant tribute to the abbey’s famous founder and to his celebration of light as the radiance of God.

Suger installed windows everywhere, great pointed arch windows lining the aisles appearing along the church’s upper floor, literally the “clear story,” or clerestory. He also put the first Gothic rose windows over the west portal and at the rear of the church, over the sanctuary. Stained glass had been used in churches before, but for Suger it became a fascination, almost an obsession. The Church of Saint Denis glowed with great kaleidoscope mosaics of colored glass showing scenes from the Bible and church history. There was even a stained glass portrait of Abbot Suger himself, kneeling at the feet of Bernard of Clairvaux’s favorite saint, the Virgin Mary.

The result was dazzling. When the sunlight poured in through Saint Denis’s windows, it would cast glowing patterns of blue, red, green, and amber gold set bright against the black of their lead frames. Transformed into rainbows of color, the light streamed and shimmered across the stone floor. If a church’s interior should be an image of heaven for the faithful, then entering the Church of Saint Denis meant entering a heaven of light and color and a radiant, eternal divine proportion.39

When Suger first stepped in his sun-filled church, he described his feelings: “It seems to me I see myself dwelling, as it were, in some strange region of the universe.” This was a region that “neither exists entirely in the slime of the earth nor entirely in the purity of Heaven.” However, “by the grace of God, I can be transported from this inferior to that higher world” thanks to the mediating power of light—or what later will be called the beauty of holiness. “The dull mind rises to the truth through material things,” Suger said, echoing the Celestial Hierarchy, “and having seen the light, [the mind] arises from its former submergence.”40

In 1144, the finished choir at Saint Denis was consecrated in an elaborate ceremony. The king of France was there and his queen Eleanor of Aquitaine. So was Bernard of Clairvaux. All around them was evidence of a new Neoplatonic spirit arising in the Catholic Church, inspiring a fresh appreciation of the physical world. It was the result of a synthesis of Saint Augustine’s belief in the power of love and faith and Neoplatonism’s belief in the power of visible order to bring the human soul closer to God.41

Thanks to Suger, Neoplatonism became virtually the property of the French monarchy and a lasting cultural legacy for France. All the most nearly perfect Gothic cathedrals until about 1230 would be built in France. Today, it is hard to find much trace of Suger’s original Gothic church at Saint Denis. Only part of the ambulatory at the far eastern end, or chevet, still survives. If we want to see the Gothic in its full original Neoplatonic splendor, we need to travel southwest of Paris by about fifty miles, to the town of Chartres.

There had been a bishop of Chartres, and a basilica, since Carolingian times. However, in about 1100 a group of scholars set up shop in the wealthy market town in order to teach local boys Latin and theology, but also to examine the complex mysteries of Plato’s one surviving text in the West, the Timaeus. When the old cathedral burned down in 1020, and then caught fire again in 1194, the so-called school of Chartres would have a direct hand in its reconstruction, including its plan and decorative sculptures.

The new Chartres was rebuilt with all the features of the Gothic style. There are the pointed arch windows and circular rose windows (including one donated by the queen of France, Blanche of Castile) and ribbed interior vaults. There is the soaring spire, almost 350 feet high, symbolizing the soul’s aspiration to be one with God. As for Chartres’s famous flying buttresses, the first ever constructed, they were built to relieve stress on the cathedral’s walls, so that windows could be available for yards and yards of glittering stained glass.

At the same time, the scholars at Chartres also gave Suger’s “style of continuous light” (they too were avid fans of the Pseudo-Dionysius) a new richness and complexity, thanks to their reading of the Timaeus. Later, some would claim they tried to replace theology with geometry.42 All they were really doing was using Plato and the Gothic style to offer a new insight into the nature of the existing world—not just to prepare for union with God in the next.

The God of Plato’s Timaeus is the Demiurge, the Architect of the Universe—in a profound sense, the Master Builder. Plato tells us He constructs the physical world from the five Platonic solids by incorporating the four physical elements—earth, air, fire, and water—in proportions to ratios such as 1:2:4:8 and 1:3:9:27. What holds Plato’s world together is literally “geometrical proportion.”43 Thanks in large part to the school of Chartres, by 1150 the image of God as Geometer was appearing everywhere, in medieval manuscripts and in statuary. And the most important geometric form of all was the cube, the only figure with a 1:1:1:1 ratio, which every student of Plato or Pythagoras knew was the symbol of divine unity or Oneness.

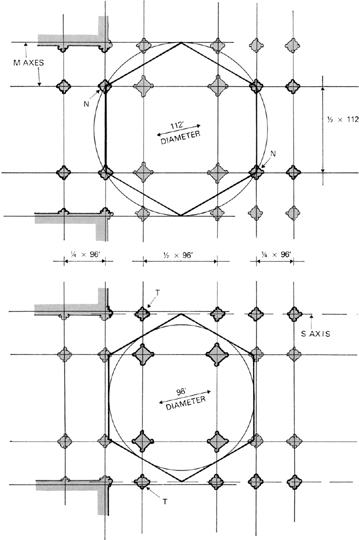

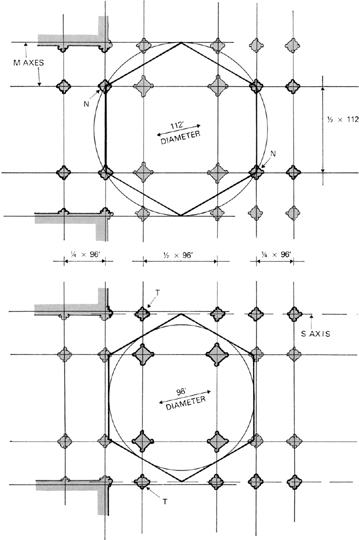

Just such a cube forms the central crossing of Chartres Cathedral. This is no great surprise. However, tipping a cube at a forty-five-degree angle will also produce a hexagon. A hexagon is constructed out of six equilateral triangles, another figure charged with Pythagorean significance. It also formed the basic figure that medieval builders used to generate their system of continuous proportion, called ad triangulum.44

Too confusing and esoteric? Not to the builders and scholars at Chartres. A mind trained by the Pseudo-Dionysius was always open to mediating symbols. The very existence of such complexity would be ipso facto proof of the work of a divine hand: proof that the order of nature enjoys a geometric perfection that must bring us closer to God.

And so, as scholar John James recently proved, the builders of Chartres Cathedral expanded the cubic space of the central crossing into a hexagonal matrix of intersecting triangles, using the vaults and pillars of the adjacent bays. These then grew out, triangle by triangle, to the next set of bays and then the next, all according to the ad triangulum formula and all in perfect proportion to one another.

Chartres Cathedral interior, with hexagons forming the central crossing

The hexagons that result do much more than define the line of columns across the transepts of Chartres. When the diagonals of the overall scheme are linked up, the position of every column in the entire building suddenly emerges. Those positions then define the positions of the windows within the rectangle of the church interior; those in turn define the height of the windows and walls; and so on. The ad triangulum principle, like a hologram, runs through every individual subunit that forms the interior of the cathedral—a dynamic exercise in proportion that is almost an exact copy of how Plato’s Demiurge in the Timaeus built the visible material world.45

Platonic geometry plays its part in the outside of Chartres as well. As scholar Otto Simson notes, the total height of the cathedral and the western portal, with its magnificent sculpted figures, follow a series of ratios based on the square and once again the equilateral triangle. (The resulting rectangles are called “golden rectangles,” since all their sides are related as a ratio of 1:2:4:8.)46

Likewise, Chartres’s famous statues of kings, queens, saints, and scholars are all arranged proportionately to one another and to the whole, since the elbow of each figure forms a golden section relative to the length of the entire figure.47 And around the portal of the Virgin Mary in Majesty are arrayed figures of the seven Liberal Arts, including Geometry, clearly the queen of the arts just as Mary is the queen of heaven.

In the Chartres portal, as in the cathedral’s school, these allegorical figures summed up human knowledge from the Gothic and Neoplatonic points of view. They symbolize the Church’s reconnection with the West’s classical heritage as an imperfect but still necessary revelation of God’s divine order. In the words of Abbot Suger’s friend the mystic Hugh of Saint Victor, “All human learning can serve the student of theology.”48

There is a female figure representing Dialectic or Logic, with Aristotle busily writing at his desk underneath. There is Rhetoric, with Cicero, similarly engaged; and Grammar, with a Roman author, Priscian, who taught countless medieval boys their lessons in Latin. In fact, one boy is shown diligently copying under Grammar’s direction, while another boy mischievously pulls his classmate’s hair.

Arithmetic is teamed with a portrait of Boethius, just as Euclid is teamed with Geometry and Ptolemy with Astronomy. Pythagoras, meanwhile, poses with the allegorical figure of Music, who chimes out her perfect melodies with a harp and a set of hanging bells.

So where is Plato? The answer is, nowhere and everywhere. At once the most famous but also the most unknown of Greek thinkers, he was transformed by the school of Chartres in the twelfth century into the great unifying intelligence of the High Middle Ages. The Gothic mind saw him as the one philosopher capable of drawing all human and divine knowledge into a harmonious whole.

Abelard had made Aristotle the greater intellectual polarizer. The anti-Aristotle backlash led by Saint Bernard put Saint Augustine in a similar polemical position. To scholars like William of St. Thierry, who knew both warring scholars, only Plato and Neoplatonism seemed to offer the possibility of an orderly synthesis, where mind, body, and spirit “have each been ordered and disposed in its rightful place,” as William wrote, “and a man may begin perfectly to know himself.”49

It was a brilliant prediction, but wrong. At the beginning of the twelfth century, one of the chancellors of the Chartres school had declared that scholars of his generation were “dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants”—meaning antiquity. By the end of the century, the men at Chartres began to realize just how gigantic those Greek and Roman minds really were. A flood of new learning was sweeping over western Europe from strange and unexpected sources. A grand synthesis was indeed in the works.

Its pivotal figure, however, would turn out to be not Plato, but Aristotle.

† This was John Scotus Erigena, one of the very few intellectuals in the Dark Ages West who could read Greek. Erigena was a Neoplatonist of some distinction. At some point, he may have left the Carolingian court for England to work as an adviser to King Alfred the Great. There, according to tradition, Erigena’s students became so frustrated with his lessons that they stabbed him to death with their pens. The story is a salutary warning to every boring teacher. Alas, it is probably untrue.

‡ The compass and T square are still their official emblem.

§ The music metaphor is appropriate since these spaces were filled with the sound of Gregorian chants, which were written to a musical scale made from the same Pythagorean proportions.

Aristotle, from the western portal of Chartres Cathedral. Thanks to the Arabs, he was about to become the philosopher for the Middle Ages.