1

PORTRAIT OF A FOOD ADDICT

Years ago, when I was in high school, a couple of my so-called friends got their hands on my medical report from a recent physical exam. They highlighted my weight and the words “morbidly obese.” They passed out copies to what felt like everyone in the school. People stared at me, laughing, and poked each other when I walked by. Some made comments under their breath. Others came right out and called me names that are still painful to repeat. See, it wasn’t just the fact that they were laughing and judging me; it was also the realization that they all knew the one thing I hated most about myself. The incident at school made me ashamed. I felt grotesque in the eyes of other people.

As a teenager, I considered myself “thick” or overweight. I knew I weighed more than was normal for my height, age, and sex, but that had been true since I was a child. I learned the hard way that there is a big difference between being overweight and being obese. I was sixteen years old when I discovered the true meaning of the term morbidly obese. Technically, obesity is a number on a table of data and is known to cause many diseases, but I experienced firsthand that being obese was doing more than compromising my health. I was in shock to find out that I was suffering from obesity at such a young age. Obesity is considered a disease marked by excessive storage of body fat and a body mass index (BMI) over 30. I was embarrassed beyond belief. I cannot tell you how hard I was on myself. My self-loathing was overwhelming.

You would think this humiliating experience would make me change the way I ate, but unfortunately, my cycles between healthy and destructive behavior only got worse. When life got too stressful, my emotions would take over. I would binge eat and build more barriers between myself and the rest of the world. This had been my pattern since I was a child.

Everyone in my immediate family was overweight. My father and brother were athletic and didn’t let their weight get totally out of control, but my mother and I always struggled. I was heavy from the start. The men in my family could really throw down. My grandfather, who is from Louisiana, prepared rich, decadent comfort food. I can still smell his seafood gumbo and rice, fried catfish coated with cornmeal—shaken in a brown bag, of course—with a side of creamy grits, and his famous barbecue ribs. My dad always got me with his sinfully rich and creamy potato salad and savory yet sweet spaghetti. Every meal was flat-out delicious. I’m talking about the type of food that makes your eyes roll to the back of your head and requires a couch and a two-to ten-hour nap afterward.

My mother’s cooking was another story. Busy working as a teacher, she was efficient about preparing meals. I am sure by now you know where this is going. She had a weekly rotation of seven dinners she repeated each week. They were square meals, meant to be healthy, but they were pretty boring. My brother and I either indulged at our grandparents’ house or ate fast food. Although Mom is definitely going to chase me with a broom after this, she, too, can admit that she depended heavily on fast food and restaurants to please us all.

There was always junk food in the house. My mother shopped at big box stores and bought everything jumbo size. I had an insatiable hunger. I remember making pantry raids like it was yesterday. She would buy a big canister of nacho cheese and an outrageously large bag of tortilla chips, which I would devour in the middle of the night as if I were in a trance. I ate stacks of PB&J sandwiches on white bread and huge bowls of salty popcorn dripping with melted butter.

Ever since grade school, I was one of the biggest kids in the class. Every time I moved up a grade, I looked around to check out if there were others who were bigger or the same size as I was. If there were others kids who were as heavy, I was relieved, because the ridicule would be shared. I wouldn’t be the sole object of my classmates’ teasing.

My parents divorced when I was very young, and though I always knew my dad loved me, deep down inside I felt he was hard on me and that there was a bit of a disconnect. He wanted the best for me, but I felt I didn’t measure up to his expectations. My older brother, who was always in some type of trouble, looked like my dad and was a “macho” athlete like him. I wasn’t as athletic. OK, I will keep this completely honest: Other than swimming, I was not really into sports. I was a go-getter, ambitious, and a great student always earning excellent grades. I guess being smart and somewhat sensitive at times, I was an easy target for the incessant reminders of all my shortcomings. My father constantly told me I was getting heavy and never hesitated to comment on the ups and downs of my weight. He pressed me to lose some pounds. Now I understand that he just wanted to make my life better, but then I only saw it as criticism, and my self-esteem plummeted even further.

My mother took me to shop in the husky clothes section, where the choice was limited to elastic-waist pants. For my eighth-grade graduation, my dad had to take me suit shopping at the Big & Tall store. Rather than the malls and department stores where my friends shopped, Big & Tall became my destination.

I wanted to be stylish. I was a skinny person in a fat person’s body. As I got older and made my own choices, I bought clothes that were too small—2X instead of 4X—which only accentuated my weight problem. I always did manage to create a well-put-together look. The sky was the limit when it came to my haircuts and shoes.

I was in denial about how overweight I was. I, like many, hit a point in my weight struggles and self-image when I became completely blinded to the reality of my situation. When I looked in the mirror, I rarely saw my overweight self. My mom and dad would remind me that when I was ten years old, I always went straight for the rack of clothes that did not fit.

When I was young and bullied because of my weight, I used two coping mechanisms to handle it: humor and food. After my braces were removed in the fifth grade, I had a bright, white smile, which I used to deflect ridicule. I developed a big personality, which wasn’t easy, given my weight-consciousness. I created a bigger-than-life alter ego who loved being the center of attention. I was funny and charismatic, the life of the party. No one knew the real me inside. I protected myself and covered up my self-hate by entertaining and pleasing people. At school, I could laugh off the jokes made at my expense and make other people laugh along with me.

I wasn’t very social outside of school. I spent a lot of time at home feeling lonely and disconnected. I created a retreat for myself in our basement where I became a prisoner of my appetite. It was a cold, unfinished basement with support poles spaced regularly throughout. The concrete floor was covered with tiles. I had an area rug to define my sanctuary space, an old, cushy gold velvet chair, and a TV with cable and VHS and DVD players. My brother’s improvised gym, consisting of some mats and improvised weights, was on the other side of the basement, not that I was ever tempted to work out there. I went to binge in the privacy of my basement screening room, away from the disapproving eyes of my mother. My weekend regimen was to confine myself to my domain in the basement and lounge in my comfy chair, watching a good movie and binging on greasy bagged food, soda, chips, and candy bars to soothe my battered psyche.

In grammar school, between fourth and eighth grade, I frequently went to the corner store that was also a hole-in-the-wall greasy spoon, where I ordered fries, pizza puffs, and gyros. My portions were way out of control. Mexican food was another vice. My meal of choice was the steak burrito with extra meat, cheese, and sour cream. If I felt the added extras were skimpy, I would politely ask for more. I would eat two days’ worth of food in one sitting. The store packed all the food I ordered in one bag along with a two-liter bottle of soda. I would sneak into the house with my stash and go straight to the basement. I could never eat enough to fill me up.

My parents wanted me to do well in school, so I never had an after-school job. When my mother gave me money, I saved it and eventually used it for my trips to the corner store. I got good at getting money from her. I’d say, “Mom, I’m going to the store—need anything? A bag of chips? An Almond Joy?” I knew she’d want something. I’d always use the change to get more food for myself, which I devoured alone in the basement. A “grammar school conman,” I would manipulate my mother to feed my food addiction. Not only did I hurt myself, but I also undermined my mother’s efforts to lose weight.

She noticed how big I was getting and started to go through the trash. She knew I wasn’t getting fat on the food she was cooking. When she realized what I was doing, she tried to restrict me. I outsmarted her by hiding my trash at the bottom of the garbage can. I didn’t think about it at the time, but pawing through the garbage to bury the evidence of my bingeing was definitely not normal. My compulsion to eat was making me do crazy things to cover up something that I knew was wrong.

By eighth grade, I weighed more than two hundred pounds.

I could tell you story after story about gorging myself on nachos, making fast-food runs at all hours, and other tales of my poor food choices. I was never satisfied, because I wasn’t nourishing my body. I was only filling it with processed, unhealthy garbage that always left me wanting more.

My mother was worried about me, especially as I was approaching high school. She was a yo-yo dieter. She had gained weight during pregnancy and had difficulty managing her weight after my brother and I were born. Trying every fad diet, she would eat next to nothing. She lost weight when she followed restrictive eating plans. But as soon as she went off these diets, she regained the weight she had lost and more.

She was so compassionate. She told me everything she had been through, and the sense of failure she felt when she couldn’t control her eating. She knew what my weight was costing me. She wanted me to be happy more than anything. She started a campaign to get me to stop eating junk food. I’d come home from school and say how hungry I was. She’d respond, “Have an apple. It will hold you over until dinner. We’re having chili.” I wanted McDonald’s—right then. I’d get angry if I couldn’t eat what I wanted when I wanted it, which was all the time. I was like an alcoholic or drug addict in withdrawal.

As a last resort, my mother put a lock on the refrigerator door. A lock couldn’t stop me. I still made runs to the greasy spoon on the corner for the food that had become like crack to me. The food and this destructive lifestyle had a stranglehold on me.

She was also responsible for one of the most mortifying experiences I’ve ever had. She made me go with her to her weight-loss group meeting. There I was, a fat, cranky adolescent boy, in a room full of overweight women. Those kinds of programs work for some people, but I didn’t connect to what they were saying in any way. I looked at the leaders of the group and knew they had not struggled with their weight the way I was struggling. I saw thin people preaching that skinless chicken and steamed broccoli were the answer. To my mind, they had no idea what it was like to be addicted to food. I was hostile and wanted them to get out of my face.

Feeling completely out of place with all those women, all I could think of, with horror, was, “What if someone I know sees me here?”

Things changed when I started high school. I had more freedom and could do what I wanted. Since I was self-conscious about being fat, I didn’t want people to see me eating. I’d go the whole school day without food. Skipping lunch in the cafeteria wasn’t hard. The food was nasty and disgusting. But I thought about food all day. When school ended at two thirty or three, I would take the bus to Wendy’s for a Frosty and two Double Stacks. Then I would return home to snack until dinner.

At sixteen, I started driving my family’s extra, old car to school. In the morning, I’d stop at Burger King and inhale two croissant breakfast sandwiches and a large OJ. I wouldn’t eat lunch. After school, I’d go to a restaurant with friends. I was self-conscious about what I ordered with them, and I never allowed myself to pig out in the company of others. I might have an order of wings and fries—no more than what anyone else was eating. No one had any idea what I did in the privacy of my binge cave.

I managed to lose weight a number of times during high school. I starved myself and worked out endlessly. I was never thin, but I did lose weight. Then my addiction would kick in. It was hard to pass a fast-food restaurant without stopping. I promised myself I would just have a taste, but I couldn’t restrain myself. I was hooked.

During my senior year of high school, I decided that since I couldn’t live without food, I had to find a way to live making food the center of my life without having to be addicted to it. It was then that I decided to study food science and human nutrition at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to learn how to approach food in a healthy way. It was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

With all the best intentions and hope that food science and nutrition would be the answer to my weight loss prayers, my weight continued to escalate during my college years. I was doing well and had tons of friends, but I still couldn’t control my eating. Although I was determined to change, it took no time for me to be tempted again. While some students gain the classic “freshman fifteen,” I gained more than sixty pounds my freshman year. From buffet style meals to deep-dish pizzas at friends’ homes to late-night food runs after partying, I found myself bigger than ever before.

Then my weight began to affect my health. I developed borderline hypertension and high cholesterol. My addiction to food was already damaging me. There are size 4 people who diet just to fit in a size 2 swimsuit, but for me, the stakes had become much higher. I wanted desperately to change.

I longed to have sex appeal. I needed to attract attention beyond “He’s cute for a fat boy,” “He’s like a brother to me,” and, my favorite, “He makes me laugh, but he’s not my type.” My need to lose weight was more urgent once my health became compromised. If I remained obese, I was writing my own ticket to an early grave.

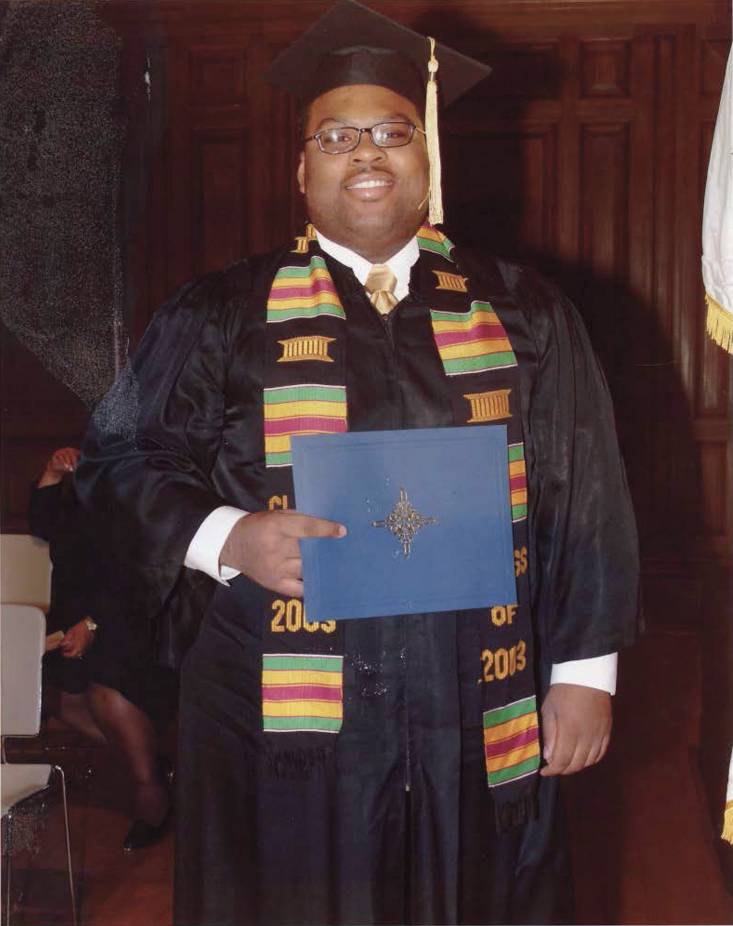

Even with this awareness, it took a visual to jolt me to change. I received a photograph of myself in the mail, which had been taken on the day I graduated from college. I had just received my degree in food science. The elated expression on my face said I was ready to take on the world, but the image before my eyes said something else. I was shocked by how I looked. At 5 feet 9 inches, I weighed more than 360 pounds, about twice my ideal weight according to medical charts. Somehow that photo caught what I had been denying for a long time. I felt as if someone had punched me in the gut.

“Why didn’t anyone tell me I’d gotten so big?” were the first words out of my mouth.

The truth was, people who loved me had tried to tell me in all kinds of ways and had been doing so for a long time. I didn’t want to hear it. Although it was fine for me to be down on myself, I was too sensitive to take criticism from anyone else, to admit what a big problem I had.

Holding that picture in my hand, I came to my senses. I realized I would never be able to change without facing the roots of my addiction to food. The struggle, pain, self-loathing, rejection, and family issues from childhood still resonated inside me. For the first time in my life, I knew I had to drop the facade I had so carefully constructed. I had to allow myself to be vulnerable if I ever was to break out of the prison of my addiction. As much as I wanted to lose weight, I had never been able to stop stuffing down my dark, agonizing feelings with food for the long term. I had to face my demons so that the real me could emerge from the armor of alienation my addiction had created. I was determined to take control of my eating, my health, and my life.

That day, when I finally realized that enough was enough, I put my education to work—for my own benefit. I had all the pieces of the puzzle: I just had to put them together. I knew the chemistry of how ingredients work together. I had learned the psychology of sensory analysis. I was prepared with techniques that I could use to achieve the flavors I wanted. Having studied nutrition, I was ready to nourish my body properly for the first time in my adult life.

I’m proud of what I have been able to achieve, but I am here to tell you that the pull to relapse never really goes away. I have armed myself with strategies that allow me to indulge my food cravings now and then without going over the top. Although I’ve kept my weight down, I am still not where I want to be. I continue to envision myself with six-pack abs, and I am working toward that goal.

When you can look back and see how far you have come, discipline becomes habitual. Just as you relied on bad eating habits to comfort you in the past, you will turn to nourishing, high-energy, flavorful food to satisfy your hunger and restore you to robust health and well-being. And, as a bonus, you will learn to make magic in the kitchen. I want The Spice Diet to do for you what it has done for me. Give it a try. You won’t look back.