6

PRELUDE TO A SCIENCE OF CITIES

1. ARE CITIES AND COMPANIES JUST VERY LARGE ORGANISMS?

The success of the network-based theory for understanding scaling laws and providing a big-picture conceptual framework for quantitatively addressing diverse questions across a broad spectrum of biology naturally leads to the question of whether this framework could be extended to understand other networked systems such as cities and companies. Superficially these have much in common with organisms and ecosystems. After all, they metabolize energy and resources, produce waste, process information, grow, adapt and evolve, contract disease, and even develop what could be characterized as tumors and growths. In addition, they age, and in the case of companies, almost all of them eventually die, whereas for cities only extremely few ever do, an enigma we shall come to consider later.

Many of us blithely use phrases like the “metabolism of a city,” the “ecology of the marketplace,” the “DNA of a company,” and so on, as if cities and companies were biological. Even as far back as Aristotle we find him continually referring to the city (the polis) as a “natural” organic autonomous entity. In more recent times an influential movement in architecture has arisen called Metabolism, which was explicitly inspired by analogy with the idea of biological regeneration driven by metabolic processes. This views architecture as an integral component of urban planning and development and as a continually evolving process, implying that buildings should be designed ab initio with change in mind. One of its original proponents was the well-known Japanese architect Kenzo Tange, the 1987 winner of the Pritzker Prize, considered to be the Nobel Prize of architecture. I find his designs, however, to be surprisingly inorganic, dominated by right angles and concrete and somewhat soulless, rather than having the curvaceous, softer qualities of an organism.

Writers, too, have often expressed organic visions of cities. An extreme example is Jack Kerouac, one of the charismatic founders of Beat poetry and literature in the 1950s, who whimsically wrote, “Paris is a woman but London is an independent man puffing his pipe in a pub.” However, it is in business that the concepts and language if not the actual science of ecology and evolutionary biology have seized the imagination, especially in Silicon Valley. The concept of a business ecosystem has become a standard buzzword to connote a sort of Darwinian survival of the fittest in the marketplace. It was introduced in 1993 by James Moore, then at Harvard Law School, in an article he wrote titled “Predators and Prey: A New Ecology of Competition,” which won the McKinsey award for article of the year.1 It’s a fairly standard ecological narrative, with individual businesses replacing animals in the evolutionary dynamics of natural selection. In keeping with much of the traditional literature on understanding companies, it’s entirely qualitative with no quantitative predictive power. Its great virtue is that it emphasizes the role of community structure, the importance of systemic thinking, and the inevitable processes of innovation, adaptation, and evolution.

Clockwise from top, images of cities: Steel and concrete skyscrapers in São Paulo, Brazil; the “organic” city of Sana’a, Yemen; the integration of town and country, Melbourne, Australia; the profligate use of energy in Seattle.

So are all of these references to biological concepts and processes just qualitative metaphors in the same way we loosely use scientific jargon like “quantum leap” or “momentum” to describe phenomena that are difficult to capture in conventional language, or do they express something deeper and more substantive, connoting that cities and companies are indeed just very large organisms following the rules of biology and natural selection?

These were the kinds of general ruminations I was contemplating when I began informal discussions in 2001–2 with colleagues at the Santa Fe Institute whose backgrounds were in the socioeconomic sciences. Fortuitously, Sander van der Leeuw, a well-known anthropologist then at the University of Paris who later moved to run the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University, was on sabbatical leave at SFI, and David Lane, who had previously run the SFI economics program, was often on-site. David was a well-known statistician who, inspired by SFI, had switched to economics. He had been chair of statistics at the University of Minnesota but had moved to the University of Modena in Italy, where he began a program oriented toward understanding innovation, especially in the manufacturing sector that had been the lifeblood of northern Italy. (You probably recognize Modena for its marvelous balsamic vinegar, not to mention as the home of Ferrari, Lamborghini, and Maserati. On my first visit there, David introduced me to their traditional balsamic vinegar, a remarkable elixir to be distinguished from the tamer stuff many of us nowadays use on our salads, but which costs a good deal more than some of the most expensive bottles of wine I’ve ever bought.)

Despite my skepticism, David and Sander convinced me that extending the network-based scaling theory from biology to social organizations was indeed a worthwhile project. They became the prime movers in putting together a broad program that covered our joint interests ranging from innovation and information transfer in both ancient and modern societies to understanding the structure and dynamics of cities and companies, all from a complexity perspective. The program was called the Information Society as a Complex System (ISCOM) and was generously funded by the European Union. Shortly thereafter Denise Pumain, a well-known urban geographer at the Sorbonne in Paris, joined our collaboration and the four of us each ran one component of the project. I assembled a new multidisciplinary collaboration centered on SFI whose first goal was to ask whether cities and companies manifest scaling and, if so, to develop a quantitative principled theory for understanding their structure and dynamics.

As in much of life, it is often instructive to take a retrospective look at what one had proposed to do long after it’s over. For instance, if I look back at the list of attendees at one of our early workshops, very few of them eventually became ongoing members of the collaboration. This is not unusual at the beginning of a program such as this that proposes to broach new questions that transcend disciplinary boundaries. At the outset all kinds of people with diverse backgrounds who are well versed in expertise that might be pertinent to the program are invited to participate in the hope that synergies will happen, sparks will fly, and a real sense of purpose and excitement about prospects for something new will be generated. Many find, however, that even if they are fascinated by the intellectual challenges and potential outcomes of the proposed project, it simply isn’t compelling enough to sacrifice the time to get fully involved and reset the priorities of their own research agendas. Others discover that they really aren’t that interested after all, or that it’s unlikely that anything of substance will come out of the effort. Eventually, however, by word of mouth, by serendipitous connections and informal discussions, and by osmosis and diffusion, an evolving group of researchers emerges whose members are to varying degrees willing to commit to a longer-term involvement with the challenge and who will actually do the substantive work over the ensuing years. Such was the process that led to the scaling and social organization component of ISCOM.2

Although its scope and emphasis broadened as progress was made, the vision of the proposal remained pretty much intact over the years. Its motivation was originally expressed as follows: “Because of the obvious analogy with social network systems, such as corporate and urban structures, it is both natural and compelling to investigate the possibility of extending the same sort of analyses used for understanding biological network systems to social organizations,” with an added emphasis that “the flow of information in social organizations is as significant as the flow of matter, energy and resources.” Many questions were asked, including “What is a social organization? What are the appropriate scaling laws? What constraints must be satisfied by the architecture of the structures that channel social flows of information, matter and energy? In particular, are the relevant constraints all physical, or might there also be social and cognitive constraints that must be taken into account?”

New York, Los Angeles, and Dallas superficially look and feel quite different from one another, as do Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto, or Paris, Lyon, and Marseille, yet their differences are relatively small compared with the differences we perceive between whales, horses, and monkey, which, as was shown earlier, are actually scaled versions of one another following simple power law scaling relationships. These hidden regularities are manifestations of the physics and mathematics of the underlying networks that transport energy and resources in their bodies. Cities are sustained by similar network systems such as roads, railways, and electrical lines that transport people, energy, and resources and whose flow is therefore a manifestation of the metabolism of the city. These flows are the physical lifeblood of all cities and, as with organisms, their structure and dynamics have tended to evolve by the continuous feedback mechanisms inherent in a selective process toward an approximate optimization by minimizing costs and time: regardless of the city, most people on average want to get from A to B in the shortest possible time at the cheapest cost, and most businesses want to do likewise with their supply and delivery systems. This suggests that despite appearances, cities might also be approximate scaled versions of one another in much the same way that mammals are.

Cities, however, are much more than just the physicality of their buildings and structures connected and serviced by various transport systems. Although we tend to think of cities in physical terms—the beautiful boulevards of Paris, the London Underground, the skyscrapers of New York, the temples of Kyoto, and so on—cities are much more than their physical infrastructure. In fact, the real essence of a city is its people—they provide its buzz, its soul, and its spirit, those indefinable characteristics we viscerally feel when we are participating in the life of a successful city. This may seem obvious, but the emphasis of those who think about cities, such as planners, architects, economists, politicians, and policy makers, is primarily focused on their physicality rather than on the people who inhabit them and how they interact with one another. It is all too often forgotten that the whole point of a city is to bring people together, to facilitate interaction, and thereby to create ideas and wealth, to enhance innovative thinking and encourage entrepreneurship and cultural activity by taking advantage of the extraordinary opportunities that the diversity of a great city offers. This is the magic formula that we discovered ten thousand years ago when we inadvertently began the process of urbanization. Its unintended consequences have resulted in an exponentially increasing population whose quality of life and standard of living have on the average also been increasing.

Road networks in Los Angeles and the New York City subway network; hidden are the other infrastructural networks, such as water, gas, and electricity.

Like almost everything else involving the psychosocial world of human beings, William Shakespeare understood our fundamental symbiotic relationship with cities. In his rather gruesome political drama Coriolanus, a Roman tribune named Sicinius rhetorically remarks, “What is the city but the people?” to which the citizens (the plebs) emphatically respond, “True, the people are the city.” Which I translate to mean: cities are emergent complex adaptive social network systems resulting from the continuous interactions among their inhabitants, enhanced and facilitated by the feedback mechanisms provided by urban life.

2. ST. JANE AND THE DRAGONS

No one is more identified with viewing cities through the collective lives of their citizens than the famous urban writer-theorist Jane Jacobs. Her defining book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, had an enormous influence across the globe on how we think about cities and how we approach “urban planning.”3 It’s required reading for anyone interested in cities whether a student, a professional, or just an intellectually curious citizen. I suspect that every mayor of every major city in the world has a copy of Jane’s book sitting somewhere on his or her bookshelf and has read at least parts of it. It’s a wonderful book, extremely provocative and insightful, highly polemical and personal, very entertaining and well written. Although published in 1961 and explicitly focused on major American cities of that period, its message is very much broader. In some ways it is perhaps more widely relevant now than it was then, especially outside of the United States, as many cities have followed variations of the classic American urban trajectory with the dominance and challenge of the automobile, the mall, the growth of suburbia, and the consequent loss of community.

Ironically, Jane had no fancy academic credentials, not even an undergraduate degree, nor did she engage in traditional research activities. Her writings are more like journalistic narratives, based primarily on anecdotes, personal experience, and a deep intuitive understanding of what cities are, how they work, and how they “should” work. Despite the explicit focus on “great American cities” in her book, one gets the impression that most of her analyses and commentaries are based on her personal experiences of New York City. She was extraordinarily intolerant of urban planners and politicians, and vicious in her attacks on traditional urban planning, especially in regard to its apparent lack of recognition that people, not buildings and highways, were primary. These classic quotes from her writing are typical of her critical attitude:

The pseudoscience of planning seems almost neurotic in its determination to imitate empiric failure and ignore empiric success.

In this dependence on maps as some sort of higher reality, project planners and urban designers assume they can create a promenade simply by mapping one in where they want it, then having it built. But a promenade needs promenaders.

There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans. . . . We can see what people like.

His aim was the creation of self-sufficient small towns, really very nice towns if you were docile and had no plans of your own and did not mind spending your life with others with no plans of their own. As in all Utopias, the right to have plans of any significance belonged only to the planner in charge.

The “his” in this last quote is a reference to Sir Ebenezer Howard, the inventor of the concept of the “garden city.” This has had a powerful influence on town planning throughout the twentieth century, providing the idealized model of suburbs around the world. Howard was a visionary utopian thinker who was strongly affected by the plight and exploitation of the working class in nineteenth-century Britain. Howard’s vision of the garden city was a planned community with distinct areas of residences (housing), factories (industry), and nature (agriculture) in prescribed proportions that he deemed ideal for providing the best of urban and country living. No slums, no pollution, plenty of fresh air with room to breathe and to live the good life. The integration of town and country was seen as a step toward a new civilized society, a curious marriage between libertarianism and socialism. His garden cities would be largely independent but managed cooperatively by the citizens who had an economic interest in them, though they would not own the land.

Unlike most utopian dreams, Howard’s vision struck a resonant chord among both liberal thinkers and hard-core investors. He was able to form a company that raised sufficient private investment to build two garden cities from scratch north of London: Letchworth Garden City (1899), whose present population is 33,000, and Welwyn Garden City (1919), now with 43,000 inhabitants. However, in order to accomplish this dream in the real world, many of his ideals had to be sacrificed or seriously compromised, including his rigid top-down design plans that Jane Jacobs railed against. Nevertheless, his basic philosophy of a planned “town and country” community has persisted to this day and has left its mark not only on the many variants of garden cities that have since sprung up around the world but also in the design concept of almost every suburban development of every city. An interesting special case of this on a large scale is Singapore. Even as the city has grown to become a major global financial center with more than five million inhabitants and has continued to build the usual ostentatious steel and glass skyscrapers, its saving grace is that it has maintained the dream of being a garden city on a grand scale. This is primarily due to its visionary top-down leader the late Lee Kuan Yew, who had the foresight in 1967 to require that Singapore develop as a “city in a garden” with abundant vegetation, open green spaces, and a sense of tropical lushness despite its chronic shortage of land. Singapore may not be the world’s most exciting city, but its ambience of greenness is palpable.

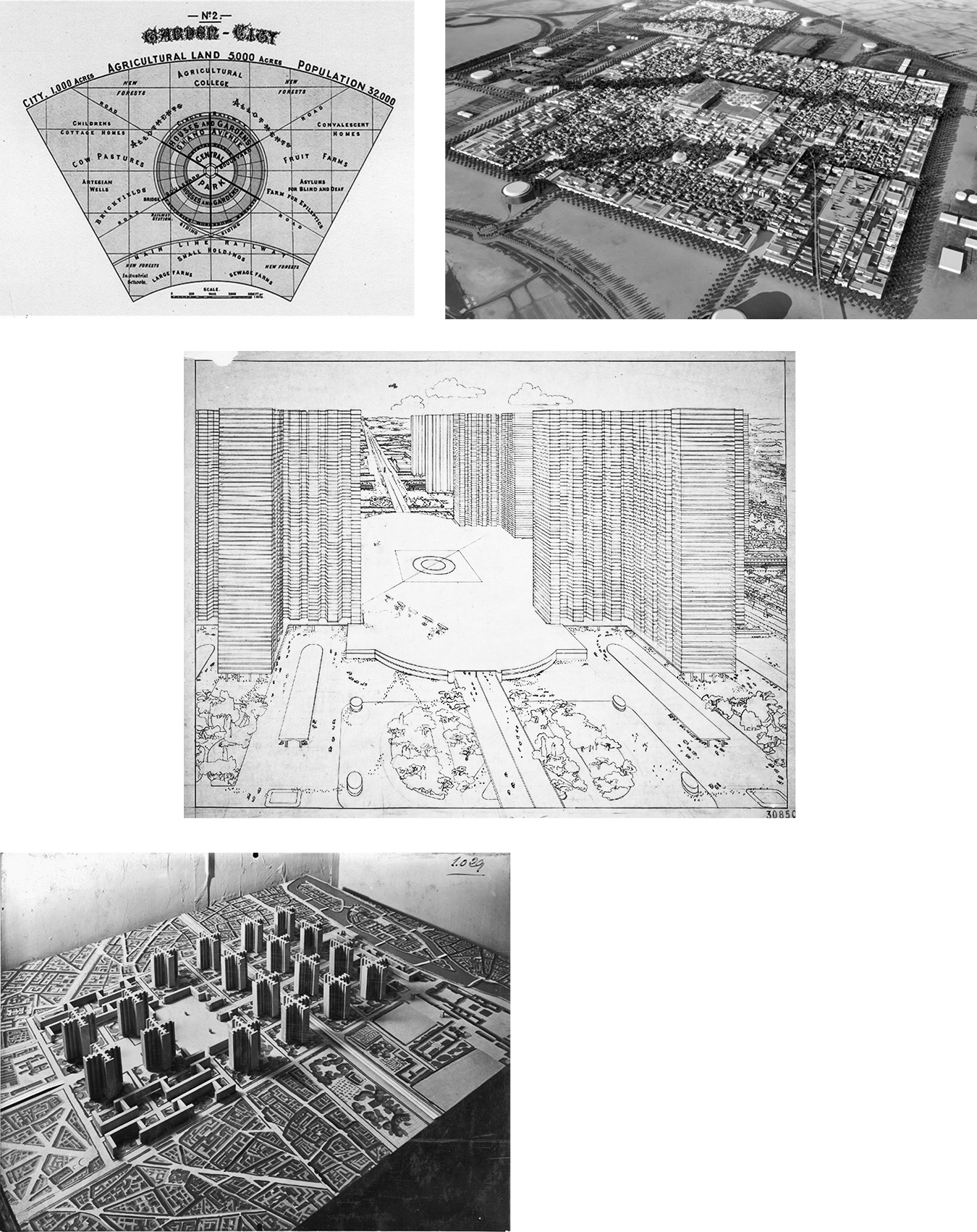

Ironically, Howard’s actual design of these garden cities was not at all organic. Their layout and organization are the very essence of simple Euclidean geometry, with the only curves in sight being perfect circles connected by perfect straight lines—the very opposite of the apparently jumbled mess of organically evolved cities, towns, and villages. No fractal-like boundaries, surfaces, or networks à la Mandelbrot appear in Ebenezer Howard’s vision of a garden city—an example of which is shown here. This move away from organic geometry became the signature of modernist movements in both architecture and urban planning during the twentieth century. It is perhaps no better exemplified than by the hugely influential Swiss-French architect and urban theorist Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, universally known as Le Corbusier, and the philosophy often referred to as “form following function.” Part of his motivation in taking this pseudonym, which was derived from his mother’s family name, was to demonstrate that anyone could reinvent themselves.

Like Ebenezer Howard, Le Corbusier was greatly influenced by the squalid living conditions in city slums and sought efficient ways to ameliorate the plight of the urban poor. Out of this concern emerged his bold proposal to erase much of central Paris (and for that matter, Stockholm) and replace it with multiple high-density concrete, glass, and steel high-rises crisscrossed with railway lines, highways, and even airports. It was all pretty stark and spartan and even a bit sinister, mimicking a turn to the right in his political thinking during the turbulent years of the 1930s. This is reflected in phrases he used such as “cleaning and purging” the city, or developing “a calm and powerful architecture,” and in his insistence that buildings be designed without ornamentation. Thank goodness that his grandiose plans were not acted upon so that we can still enjoy some of the more decadent urban embellishments of central Paris and Stockholm.

Top left: An example of Ebenezer Howard’s plans for a garden city; top right: the new city of Masdar in Abu Dhabi; middle and bottom left: examples of Le Corbusier’s design for a new city.

Le Corbusier had an enormous influence on architects and urbanists across the globe, as evidenced by the dominance of rigid steel and concrete structures that adorn the central districts of all of our major cities. Just as Howard’s urban design philosophy has left its indelible mark on suburban city life, so has Le Corbusier’s left its indelible mark on our downtown cityscape. This is especially evident in the design of new capital cities such as Canberra, Chandigarh, and Brasilia. A particularly interesting case is that of Brasilia, whose civic buildings were designed by the architect Oscar Niemeyer, who was much influenced by Le Corbusier although he qualified his admiration by declaring:

I am not attracted to straight angles or to the straight line, hard and inflexible, created by man. I am attracted to free-flowing, sensual curves. The curves that I find in the mountains of my country, in the sinuousness of its rivers, in the waves of the ocean, and on the body of the beloved woman. Curves make up the entire Universe, the curved Universe of Einstein.

To which, by the way, he might have added Mandelbrot and fractals. It is ironic that despite this admirable declaration, Brasilia became emblematic of what a city should not be. It has often been characterized as a “concrete jungle”—stark and soulless even though, harking back to the influence of Ebenezer Howard, it does have many open green spaces and parks. After visiting Brasília shortly after it was inaugurated in 1960, the avant-garde French writer-philosopher Simone de Beauvoir echoed Jane Jacobs by rhetorically asking:

What possible interest could there be in wandering about? . . . The street, that meeting ground of . . . passers-by, of stores and houses, of vehicles and pedestrians . . . does not exist in Brasília and never will.

Fifty years later, emerging from the shackles of its original plan, the city, now boasting more than two and a half million inhabitants, has slowly begun to evolve organically and develop a “meeting ground” integrated with a more humanistic livable environment. Meanwhile in 1989, just two years after Kenzo Tange received the Pritzker Prize, it was awarded to Oscar Niemeyer. Another more recent Pritzker Prize winner, Norman Foster, has also tried his hand at designing a city ex nihilo, in this case in the harsh desert environment of the Gulf States. This is the much-publicized city of Masdar in Abu Dhabi, which is envisioned to be a showcase for a sustainable, energy-efficient, user-friendly high-tech community by taking advantage of abundant solar energy enabled by sexy advances in IT. It’s a bold and exciting plan, even if it is rather a strange beast. It is planned to have about fifty thousand inhabitants by around 2025 at a cost of about $20 billion. Its main business is expected to be the high-tech research and manufacturing of environmentally friendly products to be supported by an influx of an additional sixty thousand commuters from Abu Dhabi itself. Perhaps the most bizarre aspect of Masdar is that its boundaries have been designed to be about as inorganic and unimaginative as possible—they form an exact square. Yes, a square city.

It is hard not to perceive Masdar as effectively a large private suburban residential industrial park rather than a vibrant diverse autonomous city. In many ways its philosophy is derivative of Ebenezer Howard’s garden city concept brought into the high-tech culture of the twenty-first century, except that it appears to be designed for the privileged rather than for the working poor. Nicolai Ouroussoff, who was the architecture critic for the New York Times from 2004 to 2011, suggested that Masdar is the epitome of a gated community: “the crystallization of another global phenomenon: the growing division of the world into refined, high-end enclaves and vast formless ghettos where issues like sustainability have little immediate relevance.” It’s too early to tell whether Masdar will become a real city or remain just a grandiose upscale “gated community” stuck out in the Arabian desert.

The tension between form and function, between town and country, between organic evolutionary development and the parsimony of unadorned steel and concrete, and between the complexity of fractal-like curves and surfaces and the simplicity of Euclidean geometry, remains an ongoing debate with no simple resolution or any easy answer. Indeed, many modern architects have explored, struggled, and experimented with many sides of these ongoing tensions, as for example Niemeyer’s testament rejecting the “hard and inflexible” and embracing “free-flowing, sensual curves” versus the actuality of some of his soulless concrete buildings. Think of the organic grace of Eero Saarinen’s TWA terminal building at Kennedy airport in New York City, or Frank Gehry’s whimsical concert hall in Los Angeles and his magical museum in Bilbao, Spain, or Jørn Utzon’s wonderful Sydney Opera House, and even that weird phallic symbol in London, dubbed “the gherkin,” built by the very same Foster who is building a square city in the desert. At the extreme end of this spectrum and in marked opposition to the admonitions of Le Corbusier and his disciples has been a smattering of remarkable architects like Antoni Gaudí in Spain or Bruce Goff in the United States. Both seemed unbounded in their imaginative visions and were willing to embrace the fantasy of organic structures as witnessed by Gaudí’s magnum opus, the extraordinary Sagrada Familia cathedral in Barcelona, or Goff’s Bavinger House in Norman, Oklahoma, inspired by the famous Fibonacci sequence of numbers manifested in nautilus shells, sunflowers, and spiral galaxies.

All of these innovative examples are of individual structures, but there is no real equivalent in the design of entire cities, nor in urban development beyond variations on the garden city theme. However, in the 1980s a movement called the New Urbanism arose that was an attempt to combat some of the issues inherent in an automobile and steel and concrete–dominated society where people become alienated from one another and where commuting long distances to work becomes the norm. The movement advocated a return to diverse, mixed-use neighborhoods architecturally as well as socially and commercially, with an emphasis on community structure through designs that enhanced pedestrian use and public transportation. Much of the thinking was inspired by the critical writings of the great urbanists Lewis Mumford and Jane Jacobs, who had reminded us that cities are people and not just infrastructure in the service of the automobile and corporate concrete-and-steel high-rises.

Jane Jacobs gained her fame and notoriety during the 1950s and ’60s battling plans to run a four-lane limited-access highway through Greenwich Village in New York City, where she then lived. This was the height of the period of “urban renewal” and “slum clearance” in which massive, unattractive high-rise public housing projects were erected along with major four-lane highways running through downtown city areas with little regard for the urban fabric or the human scale. The man behind all of this in New York City was Robert Moses, the powerful mastermind who reshaped and rejuvenated the infrastructure of the city over a period of almost forty years. Although he accomplished many important things for New York, including the construction of bridges and expressways connecting Manhattan to the other boroughs, he did it at the expense of destroying many traditional neighborhoods.

A major piece of Moses’s vision was to construct the Lower Manhattan Expressway designed to go directly through Greenwich Village, Washington Square, and SoHo. Jane Jacobs led the fight to stop this extraordinary encroachment, claiming that it would destroy an essential feature of the city. After a long and bitter struggle she eventually won the battle. She was much vilified during the process, and not just by politicians and developers, but by many urban planners and practitioners, including Lewis Mumford, who saw her as a flaky sentimental reactionary blocking progress and the future commercial success of New York City. In keeping with the spirit of Le Corbusier, Moses’s plans also called for multiple city blocks to be razed and replaced with upscale high-rises. Although this was carried out in many areas of the city, it went by the wayside in Greenwich Village though it did result in the development of Washington Square Village, a project owned by New York University, which was ultimately used for faculty housing. I have actually had the pleasure of staying there for short periods during extended visits to NYU. I thoroughly enjoyed it—not because I particularly enjoyed living in a typical modern high-rise apartment complex but because it gave me immediate access to the wonderfully exciting life of Greenwich Village, SoHo, and Little Italy. These are populated with all those crazy people who contribute to the urban buzz and proliferation of galleries, restaurants, and diverse cultural activities that help make New York such a great city—all of which the prophet Moses might well have unwittingly destroyed had it not been for Saint Jane the savior. New York and the rest of us should be eternally grateful to her.

Many cities across the globe have suffered from this vision of urban renewal and slum clearance, all carried out with the very best of intentions and often for good reason. However, all too often the sense of community is neglected, to say nothing of the plight of those being displaced, leading to untold unintended consequences. In too many cases seemingly exitless highways have cut through traditional neighborhoods, leading to isolated islands literally cut off from the major arteries of the city. Together with the construction of bland high-rise apartment complexes, these islands have often bred alienation and crime. In the United States it is a testament to the rallying call of Jane Jacobs that the massive highways built fifty years ago that ran through the downtown areas of major cities such as Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco have now been torn down. It is not so easy, however, to resurrect old neighborhoods and community structures that had evolved over many decades, but cities are very resilient and adaptive and will no doubt evolve something new and unexpected.

As a footnote to this piece of urban history, it is ironic that NYU’s long-term strategic plans include a proposal to redevelop the Washington Square Village complex by demolishing those very same high-rise apartment buildings and restore the area to its original structure—plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

In an interview4 in 2001 Jane Jacobs was asked:

What do you think you’ll be remembered for most? You were the one who stood up to the federal bulldozers and the urban renewal people and said they were destroying the lifeblood of these cities. Is that what it will be?

To which she replied:

No. If I were to be remembered as a really important thinker of the century, the most important thing I’ve contributed is my discussion of what makes economic expansion happen. This is something that has puzzled people always. I think I’ve figured out what it is.

Alas, she was wrong. She is, in fact, primarily remembered for her fight to preserve the integrity of lower Manhattan and for her insights into the nature of cities and how they function, including recognizing the critical roles of diversity and community in creating a vibrant urban socioeconomic ecology. In more recent years she has been beatified “as a really important thinker of the century” by much of the urban planning community but also by the broader intelligentsia and cognoscenti. Unfortunately, her contributions to economics per se for which she wanted to be remembered have not fared nearly so well and have barely been acknowledged. She wrote several books on urban economics and on economics itself, focusing primarily on questions of growth and the origins of technological innovation.

A major point throughout her writing is that macroeconomically, cities are the prime drivers of economic development, not the nation-state as is typically presumed by most classical economists. This was a radical idea at the time and almost entirely ignored by economists, especially as Jane was not a card-carrying member of the clan. Obviously the economy of a country is strongly interrelated with the economic activity of its cities, but, like any complex adaptive system, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Almost fifty years after Jane’s hypotheses about the primacy of cities in national economies were articulated, many of us who have come to study cities from a variety of perspectives have arrived at some version of her conclusions. We live in the age of the Urbanocene, and globally the fate of the cities is the fate of the planet. Jane understood this truth more than fifty years ago, and only now are some of the experts beginning to recognize her extraordinary foresight. Many writers have picked up this theme, including the urban economists Edward Glaeser and Richard Florida, but none has been as forthright and bold as Benjamin Barber in his book with the provocative title If Mayors Ruled the World: Dysfunctional Nations, Rising Cities.5 These are indicative of a rising consciousness that cities are where the action is—where challenges have to be addressed in real time and where governance seems to work, at least relative to the increasing dysfunctionality of the nation-state.

3. AN ASIDE: A PERSONAL EXPERIENCE OF GARDEN CITIES AND NEW TOWN

Following the destruction wrought by the Second World War in which millions of houses were destroyed, the socialist government in Britain faced a mammoth housing crisis. The majority of these damaged houses were in working-class areas, so this greatly accelerated the ongoing processes of “urban development” and “slum clearance” that had already been on the agenda before the war, and in which Ebenezer Howard’s idea of garden cities was a classic visionary example. By the 1950s and ’60s the preferred model for new housing had evolved from the traditional British desire for a single-family house to the more efficient building of high-rise apartment complexes. These were of mixed success and raised many of the issues we’ve already discussed. Will Hutton, a political economist at Oxford and formerly editor in chief of The Observer newspaper, commented as recently as 2007:

The truth is that council housing is a living tomb. You dare not give the house up because you might never get another, but staying is to be trapped in a ghetto of both place and mind. . . . [C]ouncil estates need to be less cut off from the rest of the economy and society.

As part of this new postwar housing program the British government embarked on creating a series of “New Towns” in order to relocate people from poor or bombed-out urban areas. Their design was inspired by the perceived image of garden cities as the wave of the future for the working class with residences in a countrylike setting and factories located in a separate enclave. The first of these was Stevenage, which was designated a “New Town” in 1946 and where I lived for almost a year in 1957–58. So I actually have some personal experience of what living in a garden city is like.

To my great astonishment I had been offered a place at Cambridge University in Gonville and Caius College to begin in the autumn of 1958 when the new academic year was to commence. So toward the end of 1957 I summarily quit my school in the East End of London and got a temporary job in the research labs of International Computers Limited (ICL), also known as the British Tabulating Machine Company, located in Stevenage.

Like any teenager living away from home for the first time, this was a defining experience and I learned a great deal during that period. From the many new vistas that opened up before me, there are three that are of relevance to this narrative. First, and the most obvious, is that working in an innovative research environment that allows and even encourages freedom of thought and movement beats laboring in the confines of a brewery mindlessly feeding a machine with beer bottles.

The second was that Jane Jacobs, who I suspect had never actually been to a garden city despite her damning comments about them, was right. It was many years before I came to know who Jane Jacobs was, but I quickly came to see that, compared with living in a somewhat run-down Victorian row house in lower-middle-class northeast London, Stevenage was like living in a fancy country resort. And that was its problem. Just as Jacobs sarcastically remarked a few years later: it was a “really very nice town if you were docile and had no plans of your own and did not mind spending your life with others with no plans of their own.” Although this is pretty harsh, it does capture that sense of boredom, routine, isolation, and benign “niceness” hiding and suppressing inner passions that later became associated with suburbia. Not that Hackney and the East End of London were paragons of urban bliss; nor, by the way, were Greenwich Village, Little Italy, or the Bronx, despite Jane’s protestations. It has become fashionable to nostalgically romanticize working-class London and wax eloquently about community in inner city life, but the truth is that it was dirty, unhealthy, rough, and tough, with its own version of architectural dreariness and the potential for loneliness and alienation. However, these were mightily compensated for by action, diversity, and a pulsating sense of people participating in life with ready access to museums, concerts, theaters, cinemas, sports events, gatherings, protest meetings, and all of the marvelous amenities a traditional city has to offer.

These were the early days of commercial computers, and like IBM in the United States, ICL was developing both old-fashioned vacuum tube and new transistor-based machines programmed by the dreaded Hollerith punched cards. We of a certain age all remember them with a kind of nightmarish nostalgia. As a graduate student at Stanford some years later I developed a passionate hatred of those awful cards and the tedious routine of programming in languages with weird names like Fortran and Balgol. Too bad, actually, because it turned me off to computer development and programming forever so that, even though I was reasonably good at it and was present “at the beginning,” both in Stevenage and in what became Silicon Valley, I didn’t have the foresight to see that computers would be useful for anything beyond doing complicated calculations and analysis. No doubt that’s why I ended up being an academic of modest means rather than a wealthy product of the Stanford entrepreneurial IT machine.

The third vista that opened up was a glimpse into the sophistication and potential power of what electrical circuits could accomplish. From a few very simple modular units (resistors, capacitors, inductors, and transistors) connected by wires in clever and complicated ways following very simple rules, something miraculously powerful and “complex” emerged that could perform extraordinary tasks at lightning speeds—this was the electronic computer. This was my introduction to the primitive concept of networks, emergence, and complexity, though none of those words nor any of that language had yet been articulated. Once I entered the life of a student at Cambridge, all of this was completely forgotten. But some of it must have unsuspectingly remained buried deep in my unconscious waiting to emerge forty years later when I began to speculate that networks form the fundamental scaffolding for understanding how our bodies, our cities, and our companies work.

4. INTERMEDIATE SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

My aim in this brief and somewhat personal digression is not to give a comprehensive critique or balanced overview of urban planning and design but rather to highlight some of its specific characteristics relevant for setting the scene and providing a natural segue into the possibility of developing a science of cities. I am not an expert, nor do I have credentials in urban planning, design, or architecture, so my observations are necessarily incomplete.

One important insight that resulted from these observations was that most urban development and renewal—and in particular almost all newly created planned cities such as Washington, D.C., Canberra, Brasilia, and Islamabad—has not been very successful. This seems to be the consensus among critics, experts, commentators, and the like. Here’s the popular travel writer Bill Bryson offering sarcastic comments about Canberra from his book Down Under:

Canberra: There’s nothing to it!

Canberra: Why wait for death?

Canberra: Gateway to everywhere else!6

It is notoriously difficult to make an objective judgment about the success of a city. It is not even clear what characteristics and metrics one should use to determine success or failure. Measurements of psychosocial phenomena such as happiness, fulfillment, and the quality of life do not readily lend themselves to reliable quantification, let alone to being modeled. On the other hand, the more concrete characteristics of life such as income, health, and cultural activities clearly do. Much of what has been written about the success of cities is not much more sophisticated than elaborations on the sort of anecdotes I’ve already quoted and is, at best, intuitive analysis based on narratives much in the style of Jane Jacobs or Lewis Mumford.7

There are many academic sociological studies based on interviews and surveys that try to develop a more objective, “scientific” perspective. Urban sociology as a discipline has a long and illustrious but somewhat controversial and often surprisingly parochial history—it was even used by Robert Moses to justify blasting highways through traditional neighborhoods. However, with all of that in mind, it does seem clear that to varying degrees almost all planned cities end up being soulless and alienating, lacking a buzz of popular and cultural activities and with a general dearth of community spirit. Relative to the promises and hype that have usually accompanied the building of a new city or a major urban redevelopment, it’s probably fair to say that almost none of them meet their expectations and many could be characterized as failures.

However, cities are remarkably resilient, and being complex adaptive systems are continually evolving. For instance, for many of us, Washington, D.C., was a noncity that we only visited for historical or patriotic reasons, or because we needed to do business with the government. It was pretty deadly and a bit of a concrete jungle dominated by massive government buildings often projecting that eerie sense of a Kafkaesque bureaucracy oddly reminiscent of the old Soviet style.

Look at Washington now—despite its many problems, it has evolved into a highly diverse and vibrant city that has attracted large numbers of ambitious and creative young people enticed by its sense of action and community. The larger metropolitan area now has an expanded economy that is no longer solely dependent on government jobs. And almost magically, those government edifices don’t look quite as menacing any longer, softened by the proliferation of many excellent restaurants and gathering places brimming with young people from all over the world. It’s taken a long time for Washington to become a “real” city, a place that even Jane Jacobs might have admired. There is hope.

This brings me to another important point. In the grand scheme of things, it probably hasn’t mattered very much that these new inorganic planned cities, such as Washington, Brasilia, or even Stevenage, were “failures” in that they weren’t exciting places abounding with opportunities for people to live fulfilling lives, expand their horizons, and feel that they are part of a vibrant creative community. Cities evolve and eventually develop a soul, though it might take a long time. Furthermore, in the not-so-distant past there were proportionately many fewer people living in urban environments and many fewer planned cities. However, because urbanization has been expanding exponentially—recall that when averaged over the next thirty years, we are adding the equivalent of a new city of almost a million and a half people to the planet every week—this situation has utterly and completely changed.

Now it really matters. To accommodate the continued exponential increase, new cities and urban developments are being built at a truly astonishing rate. China alone will be constructing two to three hundred new cities over the next twenty years, many with populations of over a million, while megacities that already dominate the developing world continue to expand, many of them spawning slums and informal settlements as more and more people flock to cities.

As I remarked earlier, megacities of the past such as London and New York suffered from much the same negative image associated with megacities of today. Nevertheless, they developed into major economic engines offering huge opportunities and driving the world’s economy. Here’s the problem: cities do indeed evolve, but they take many decades to change and we simply no longer have the time to wait. It took 150 years for Washington, 100 years for London, and more than 50 years for Brasilia, which is still very much a work in progress. Added to this is the sheer scale of the problem. China has embarked on the daunting task of constructing hundreds of new cities to urbanize 300 million rural residents. Out of expediency, these are being built without any deep understanding of the complexity of cities and their connection to socioeconomic success. Indeed, most commentators report that many of these new cities, like classic suburbs, are soulless ghost towns with little sense of community. Cities have an organic quality. They evolve and physically grow out of interactions between people. The great metropolises of the world facilitate human interaction, creating that indefinable buzz and soul that is the wellspring of its innovation and excitement and a major contributor to its resilience and success, economically and socially. It is shortsighted and even courting disaster to ignore this critical dimension of urbanization and concentrate only on buildings and infrastructure.