FOR WHATEVER REASON we enter into psychotherapy, our goal is the same: to gain better control over our thoughts, feelings, and actions so that we can achieve a relatively peaceful and genuinely healthy internal state and lead a more productive life. What we usually find is that for some reason we have adopted certain automatic ways of regarding ourselves and responding to the world around us that are unhealthy and need to be reorganized. This is true whether we’re depressed, anxious, bipolar, obsessive-compulsive, attention-impaired, or dissociative.

For people with a dissociative disorder, the process of regroupment is intrinsically more complicated because they have more than one internal state in need of reorganization. They may not even be aware of the separate parts of themselves—”hidden“parts, as I’ve called them—that are not under their control. All they know is that at times a “mood” comes over them or some inner “demon” makes them act in an angry, panicky, or childish manner that seems completely out of character.

At their worst, these angry outbursts, panic attacks, and childish regressions can make them dysfunctional, as the case histories you’ve just read have shown. Jean, an A student, became so panicky in Spanish class that she got F’s when Cave Girl, a hidden part that developed in childhood to protect her from violence and sexual abuse, came out in college. Linda, who loved her fiancé, was overcome by an aversion to intimacy and wouldn’t let him touch her when the traumatized fourteen-year-old rape victim inside her took control. When Nancy’s hidden parts were in control, this model wife, mother, and professional lashed out at her family in uncontrollable rage and became too childlike to be able to work.

Unlike these people, you may have dissociative symptoms that are all mild, but you could still have qualities that are not within your control as much as you would like them to be. They’re not separate personalities, but they can be unruly emotions or types of behavior that are working against you in your personal life or on the job—troublemakers like angry outbursts or runaway anxiety or childish neediness or relentless self-criticism or unwarranted feelings of gloom and doom. You’ll find that the method of treatment that I use for people with a dissociative disorder can readily be applied to helping you achieve greater mastery over any of these errant tendencies.

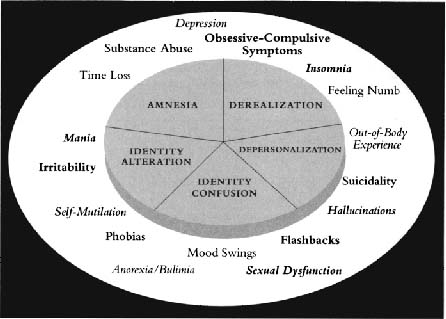

Now that you’re familiar with the five core symptoms and the ways they manifest themselves, it’s important to remember that whatever symptoms you may have—depression, panic attacks, substance abuse, mood swings, et cetera—may be external manifestations of an underlying dissociative problem. Unless that deeper problem is detected and treated appropriately, you will not recover fully.

The accompanying figure of a circle within a larger circle shows that your symptoms may be external or surface manifestations of internal or deeper symptoms of dissociation—the five core symptoms. If a symptom in the outer circle is treated without regard to the symptoms in the inner circle, the external symptom may get better, but it will recur, or another external symptom will develop. When internal core symptoms are detected and treated properly, external symptoms will diminish significantly or be eliminated entirely.

The link between the symptoms in the inner circle and those in the outer one can be made only by having the full SCID-D done. Substance abuse, for example, may be related to a person’s trying to self-medicate inner feelings of detachment from himself or his emotions—symptoms of depersonalization. Similarly, someone who has regressed to a childlike state and finds himself in a situation he doesn’t understand may experience panic attacks. He may complain of panic, but the panic is related to identity alteration—the fears of a childlike part that has suddenly taken control. Since any treatment’s successful outcome is critically dependent on an accurate diagnosis, having a clinician make the connection between surface symptoms and deeper ones is essential.

Reprinted with permission from M. Steinberg, Handbook for the Assessment of Dissociation: A Clinical Guide. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1995.

What differentiates treatment for dissociation from the usual talk therapy is that it gives you a new way of relating to yourself on a deeply nurturant level. Its strategies help you to accept and respect the different sides of yourself by communicating directly with them in a comforting way and encouraging them to cooperate with each other and connect into a functioning whole rather than remain in conflict. The four C’s on which this therapy is based—comfort, communication, cooperation, and connection—are especially helpful for people with a traumatic past who have dissociated from it in order to survive. Even if your history was much less traumatic than those described here, this process can help you accept your past while maintaining control over your emotional responses to your memories.

Therapy for people with DID is designed to gently bring down the walls of amnesia that keep their different parts hidden from themselves and each other. Most experts agree that the key to treating dissociation lies in the connection, or integration, of memories, feelings, and behaviors. The process is like connecting the dots in a child’s coloring book. The dots are the person’s different parts, and the connections are the memory links that have to be built. Once the person feels safe enough to accept the memories, the amnesia, as well as the other dissociative symptoms, is reduced, and the person becomes connected just as the picture in the coloring book becomes whole.

Some people with a dissociative disorder are able to integrate their separate parts into a single, congruent self-image. Others may fear that integration means the “death” of their alternate personalities and may not want to give them up. They may continue to have separate parts but can achieve “functional cooperation” between them, which is a giant step on the path toward healing and recovery. Nancy may retain aspects of the Child, for example, but she has built an increasingly positive source of identity in the Mom. Now she is able to monitor her internal states and marshal her inner resources in times of stress, as she did when she had flashbacks of her father’s sexual abuse. Cooperation between her separate parts has also enabled her to regulate her emotions more effectively so that her misdirected rage at her abusive mother embodied in the Mean rarely comes out anymore. Now she can maintain her inner equilibrium when she interacts with family members who trigger memories of her mother’s cruel treatment of her or the frightening violence of her childhood alcoholic household.

Studies have shown that this kind of specialized treatment for people who have a dissociative disorder, when combined with medication for such symptoms as mood swings, depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive behavior, is highly effective. Richard P. Kluft, M.D., reported that 81 percent of 184 DID patients he treated achieved “stable fusion,” meaning that all signs of DID and related symptoms were absent for at least twenty-seven months. Regular follow-up visits for as long as two to ten years after treatment ended showed that these patients maintained a complete absence of clinical signs of a dissociative disorder. For a large subgroup of these patients who were high-functioning before they were diagnosed with DID, their treatment averaged two and a half years of a minimum of two forty-five-to fifty-minute sessions a week. Most patients who achieved integration discontinued treatment and remained essentially well during the follow-up period. Recent research indicates that length of treatment varies, three to five years being the average.

There is a process of discovery that needs to take place before the actual work of therapy can begin. During this process you explore whether or not you have detached from your identity, your surroundings, or your memories, and, if you have, what are the different parts that exist within you. Do you have a Cave Girl or a Wailing Woman, as Jean did? If your dissociation is less severe than Jean’s, you may just be aware of acting differently from the way you normally do at times—behaving like a child, throwing temper tantrums, saying things that are uncharacteristic of you in verbal outbursts, or behaving in other ways that are not in your control.

These hidden parts are likely to emerge when you’re under stress. You may be able to cope when things are going smoothly, but when you’re in the midst of a conflict or a stressful situation, you might start acting in ways that are out of character or have an out-of-body experience and not recognize yourself in the mirror, or feel that you’re removed from what’s going on. It’s as if you’ve hidden away your feelings in a closet, and the closet is full. Then one day something stressful happens, and once again you stuff your uncomfortable feelings into the same closet. Since there’s no more room, the feelings from twenty years ago come tumbling out, and you respond to the present situation in an uncharacteristic manner. In Linda’s case, for example, her overreaction to being arrested by the police officer was fueled by unresolved feelings of anger at her rapist that had been hidden away since she was in her teens. Once those angry feelings were out of the closet, they took over whenever her fiancé tried to become intimate with her.

If you have hidden parts of yourself that are disrupting your life, unless you identify them, you can never get better. These parts have been hidden essentially for safekeeping. They need to emerge and be acknowledged and accepted in order for you to heal from the abuse or trauma that caused you to shelve them in the first place. By answering the questionnaires on each of the dissociative symptoms adapted from the SCID-D in the previous chapters, you’ve taken the first step in this process of identification. At least you are now aware of what the symptoms are and how they manifest themselves, so that you can knowledgeably describe them to a therapist. Your test scores are only a preliminary indication of whether your symptoms are serious or not. The administration of the full SCID-D by a trained clinician is what will allow you to gauge the severity of your actual symptoms and identify whatever hidden parts you may have.

Although I present the four C’s of treatment in a particular order, they are all somewhat intertwined. Comfort generally does come first, but communication occurs simultaneously and is also involved in the work of cooperation. There is an element of connection, the last stage, in that first phase of comfort. As a person works through all these phases—identifying the dissociated parts, comforting them, communicating with them, enlisting their cooperation with each other, and connecting to them in the sense of owning their emotional memories so the abuse or trauma is no longer perceived as having happened to someone else—integration is a natural by-product. With the flow and sharing of memories, knowledge, and feelings back and forth, the barriers erected by amnesia gradually erode over time, and each fragmented part enters the mainstream of the person’s identity.

To make yourself feel safe enough to bring dissociated memories and feelings out of hiding, you need two sources of comfort: internal (within yourself) and external (environmental).

The most obvious forms of external comforting are making your home a comforting place and connecting to people who can be supportive. On a more profound level, you need to take measures to reduce and eventually eliminate stress from abusive or destructive relationships. Nancy’s decision to minimize contact with her still emotionally abusive mother was a big step in this direction, as was Jean’s initiation of divorce proceedings to end her demeaning and exploitative marriage.

Since all dissociatives have been taught that their emotions must be either invalidated or denied in order to survive, learning to trust your emotions sufficiently to make these decisions is a process that therapy can help you address. Building supportive relationships and a stress-free zone within therapy and outside ensures that healing and recovery will not be impeded by the continuing bombardment of external poison arrows.

Internal comforting is a huge problem for people who have been exposed to any kind of abuse or trauma. They are terribly deprived of self-comforting skills because appropriate comfort has not been role modeled to them. They were raised by people who have violated their trust or their boundaries, have betrayed or neglected them, or have been too remote from them to be relied upon for emotional support. Since comforting themselves is a foreign concept to them, they doubt their ability to do it. They also need to learn that they’re worth comforting, as Nancy said, and that’s a difficult task for someone who was so invalidated in childhood as not even to feel real, let alone worthwhile.

People who have disconnected from their emotions because they’re frightened of them often perceive the dissociated part of themselves as destructive and want to get rid of it rather than comfort and respect it. Nancy, for example, was initially desperate to get rid of the Mean. Attempting to get rid of any dissociated part is not going to work, because that part has served a valuable function in the person’s life and is holding important memories that need to be accessed and accepted.

Wonderful Ways to Love a Child by Judy Ford is a concise little guide to parenting a child and can also be used to learn various ways of accepting yourself and giving yourself love. It offers such suggestions as Listen from Your Heart, Speak Kindly, Try to Understand, Ask Their Opinions, Allow Them to Love Themselves, Honor Their Noes, and Celebrate Mistakes. One suggestion, Let Them Cry, is particularly meaningful for dissociatives. They’re often afraid that once they start crying over the painful memories and feelings they’ve buried away in a hidden part of themselves they’ll never be able to stop. That’s where the work of comfort comes in. When people are able to comfort their hidden parts sufficiently, two things happen: they don’t have to keep them under wraps anymore and they don’t become dysfunctional with them out. Comfort gives people the strength to stop hiding their tears and to stop crying after they’ve shed them.

The Woman’s Comfort Book by Jennifer Louden, a book clearly not written for the dissociative population but for everyone, is filled with detailed and explicit strategies for comforting every disturbing feeling you might have—afraid to be alone, angry, burned-out, can’t sleep, confused, depressed, emptiness, exhausted, feeling fat and ugly, had an awful day, inadequate, lonely, needy, nervous, scared, self-loathing, trapped, temper tantrums, and so on. The strategies range from Your Nurturing Voice and Creating a Comfort Network to Nutritional Music and A Forgiveness Ritual.

One of the strategies in The Woman’s Comfort Book, Reading as a Child, is introduced this way: “Reading children’s books is a simple but very effective way to comfort ourselves. We can reconnect with innocence, magic, and hope.… Reconnect with wonder, and comfort the part of yourself that is still a child.” I have found that children’s books address self-comforting issues in a very simple but powerful manner that relates to people of all ages.

The purpose of using children’s books in therapy is to help people understand the comforting process and develop a language for it. Loving, caring parents read comforting stories to their children and act in a consistently nurturing manner, employing a rich repertoire of supportive techniques for their children to experience and replicate. By contrast, abused children may not have had exposure to comforting books and have not had sufficient experiences in real life to strengthen their self-comforting abilities. For these children self-comfort may exist only in fiction, in their fantasies, or not at all. By reading children’s books and learning how loving parents care for their children, people can learn to apply these basic approaches not only to their own children, but to themselves.

Part of the pleasure we derive from reading to a child is that the soothing message of the book soothes the reader as well as the listener. As an adult you may find reading a child’s book strange or silly, but it can be very effective. Reading children’s books that deal with comfort and safety or rereading your favorite childhood books can help you recognize the need for comfort and compensate for some of the comforting that was unavailable to you when you were growing up. When you read these books, try to think about the basic ingredients of comfort—which strategies you were exposed to and which were lacking. If you feel foolish reading these books, try reading them to a child. As you do, be aware that you can both share in the lessons of these stories. The idea is to begin to develop a supply of comforting skills that will enable you to withstand life’s stressors, including painful memories from the past or ongoing pressures today.

Besides being a useful tool for anyone, child or adult, who has ever had trouble falling asleep (an extremely common problem amongst abuse survivors), Martin Waddell and Barbara Firth’s Can’t You Sleep, Little Bear? helps the reader learn about the range of comforting techniques available in general. As the title suggests, Little Bear cannot fall asleep because he is afraid of the dark. Using the cub’s father, Big Bear, as a guide, the book takes the reader through a number of ways in which an adult can attempt to relax a child. At first, Big Bear thinks Little Bear is afraid of the darkness in his room, so he hooks a lantern over the young cub’s bed. When Little Bear is still afraid, Big Bear brings him a book. When Little Bear still can’t fall asleep, Big Bear hooks a bigger lantern over the bed, then an even bigger lantern, then The Biggest Lantern of Them All. Finally, Big Bear realizes it’s not the darkness inside that frightens Little Bear, but rather the darkness outside. So he takes the cub outside of the cave, lifts him up, cuddles him, and tells him to look up at the dark. Big Bear shows Little Bear the moon and the stars until the cub finally falls asleep, feeling warm and safe inside his father’s arms. Similarly, adults who fear the terrors of the night as children do, or are haunted by other fears, can comfort themselves with light and love. Just as Big Bear comforted Little Bear, we, too, can remind ourselves that the darkness that makes us afraid also holds the moon and the stars.

Mordicai Gerstein’s The Wild Boy explored the power of love and comfort on a boy who was found living alone under harsh conditions in the woods of Aveyron. Raised by himself, the boy’s life was filled with physical violence and basic survival. Unresponsive to any human contact, he was evaluated at the Institute for Deaf-Mutes in Paris, where he was befriended by Dr. Itard. Itard immediately recognized the classic symptoms of “a boy who had never been held or sung to or played with,” and “who had never learned to be a child.” After naming the boy Victor, Itard decided to raise him himself. As Itard showers him with consistent love, a new home, and much-needed attention, Victor gradually begins to respond and express feelings of joy, sadness, comfort, and safety. After reading this book, those who are confronting their own inner “wild child” may likewise find themselves’ accepting that aspect of their personality, rather than disrespecting it for its lack of control and civility. They may finally be ready to befriend the stranger within.

Basically what abuse survivors need to do is learn how to parent themselves. If they’ve been a good parent to their children or kind to friends, they have these skills. They just haven’t applied them to themselves. They would rush to comfort a screaming son or daughter, yet they ignore the parts of themselves that have been screaming in pain for years. Jean was willing to let the Wailing Woman cry forever rather than comfort her pain over unintentionally killing a man and redirect her grief into a positive act. Similarly the horrified little girl locked up in prison or screaming at the table the night Jean’s father was stabbed to death would go on screaming and screaming, frozen in time, compartmentalized forever if Jean hadn’t reached out to comfort her. By making the little girl feel loved and safe, Jean was able to begin the process of unfreezing her and gradually accepting her into her life today.

Dissociates who’ve survived abusive childhoods are often able to be excellent parents, never wanting to do to their children what was done to them. Parenting is a constant struggle for them because of all of the inner turmoil they’re experiencing. Many of them have children who’ve been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as were Nancy’s son and daughter, Linda’s daughter, and Jean’s two daughters. Dissociation is much less commonly identified by child psychiatrists, so it’s possible that a child identified with ADHD could have an underlying dissociative basis for the ADHD symptoms or a coexisting dissociative disorder. A characteristic feature of ADHD is inattention—essentially, memory problems—and loss of memory is also a core feature. Another is the fluctuation between high functioning and low functioning or scattered performance—a child gets an A and an F in the same semester. ADHD might be one explanation for that; another might be that the child has different parts of herself, like Jean, who had Knowledge and could get all As, and Cave Girl, who couldn’t be in school at all.

One strategy for self-comfort when you feel disconnected is to make physical contact with objects in the immediate environment—press your shoulders against the back of the chair you’re sitting in, for example—and state your name, location, and safe circumstances to yourself. Jean was able to ground herself to the present time, for example, by saying, “I’m Jean W.; I’m in school now; and no one is going to hurt me here.” You might remember how Tom, the former boxer who had a warrior-type personality within him named Wild Tom (Chapter 9), used a grounding technique to help himself stay centered in the present. Whenever he felt on the verge of exploding in rage, he looked at the miniature boxing gloves on his key chain, a symbol of comfort and safety, and reoriented himself to the present time. He realized that he was not in the boxing ring with a dangerous opponent or fighting for his life with his father, and didn’t need to protect himself by savagely beating up someone. Tom used a verbal grounding technique as well. To prevent himself from flying into a jealous rage when he saw his wife talking to another man, he told himself: “My wife loves me. She is having a harmless conversation with an acquaintance, and this is not a dangerous situation.” Such grounding techniques are quick ways of stopping an automatic flip back into the past when some trigger sets it off.

Another strategy for coping with dissociative episodes is to turn to an absorbing external activity that you enjoy. Reading, handicraft work, exercising, conversing with others, and so on, can interrupt the cycle of escalating thoughts and feelings that lead to a sense of disconnection from yourself or your body or a feeling of unreality.

The technique that Ted used with Linda to calm her panic attack—helping her visualize that they were out sailing on a calm sea—can also be an effective way to manage a depersonalization episode. Visualizing a safe place or a sanctuary; recalling pleasant memories, particularly of supportive adults from your past; and using religious or spiritual imagery that is meaningful to you can all help to rein in your galloping overreaction to triggers in your environment or in your intimate relationships.

Triggers of depersonalization abound in intimate relationships for people who have survived abuse or trauma. Many people experience depersonalization in the presence of family members who have abused them. Others experience the symptom in the presence of romantic partners or spouses who trigger memories of their original abusers. Linda’s fiancé reminded her of her rapist, for example, and Jean’s seductive professor brought to mind her brother’s sexual abuse. Still others experience these episodes whenever any of their significant relationships breaks up or appears to be in jeopardy. It’s as if they feel that their fragile sense of identity cannot withstand the loss of the other person who has been the glue holding it together. It was Nancy’s fight with her husband and her fear that she might lose him that precipitated her shocking episode of depersonalization and regression into a childlike state.

Experience in the use of creative visualization and the other self-comforting techniques can offset the kind of severe depersonalization episode that might land a person in a hospital emergency room. Jean, Linda, and Nancy all managed to stay out of the ER once they had developed a number of strategies for comforting themselves.

Comforting oneself is something that everyone needs to do on a daily basis, and most people naturally gravitate toward this by regularly going to the gym, listening to music, meditating, pursuing a hobby, reading, watching a movie, going out to dinner with friends, jogging, or doing whatever suits them. Dissociatives have to make an effort in the early phase of treatment to think about comforting and build a lengthy repertoire of comforting skills. I ask people to make a checklist with the days of the week and a listing of things that they can do that comfort them. I recommend that they do something comforting every day and that they take the list into therapy so that I can see where they’ve checked off what they’ve done on each day.

One of the most important comforting skills that you can have is the ability to conduct positive dialogues with yourself—so important, in fact, that acquiring this skill can be considered a separate phase of treatment in itself. The goal is to build an inner voice that can respond effectively to the voice of fear, rage, sadness, or disparagement within yourself that resulted from trauma or abuse.

Just as many corporations have a “mission statement” that conveys in a few short sentences what the company is all about, it is useful to draft a mission statement that offers guidance for each separate part of yourself. In a sense this mission statement is like an affirmation, except it is individualized to address the issues of whatever part of yourself needs to be comforted.

Jean’s mission statement for the Wailing Woman was “I respect and care about your sadness and want you to know that you no longer have to carry this burden all alone. You can depend on me to help you with your tears and find a way to ease your suffering. I am here for you.”

For Cave Girl, Jean had a different mission statement to address her fear of coming out of the cave and having to deal with people: “Now it’s safe outside, and you can come out and see the light of day and begin to walk freely. You are no longer alone. I will be with you.” Because the “I” was the adult Jean or Knowledge, this was not only a mission statement, but the start of connection between Cave Girl and the other parts.

In Linda’s case, she had her own positive mission statement when she was with Ted that helped to ground her: “This is today, and I’m in a safe home. This is my home; there are no rapists here. I am with a man who loves me, and love doesn’t mean I’ll get hurt. There is no need to push him away.”

Nancy’s mission statement for the Mean was “I appreciate your keeping my anger safe for me. Please let me know why you’re so angry and what I can do to comfort your anger.” For the Child her mission statement was “I understand how frightened and sad you are, but there is nobody here who will hurt you or leave you if you’re not perfect. You are a good child. You are safe now. I will protect you.”

The theme of all of these personalized mission statements is the sense of responsibility that dissociatives have for their different parts and how they need to work together to end the state of being detached and bring about wholeness. The coordinator is the primary self—the one who is present or in control most of the time. In our business analogy, the primary self is like the CEO or chairman of the board of the corporation who sets the course of building connections among the different parts and having them pull together to reach the goal of integration.

Everyone can benefit from a personalized mission statement directed toward achieving an inner life of health, balance, and wholeness. Even if you’re not aware of a completely separate part of yourself, you could have a side that needs a message of encouragement and hope from you or from your external support system under certain circumstances. You may have an angry side that prompts you to have temper tantrums or an abandoned, lonely “inner child” that makes you abuse alcohol or become overly needy in relationships or feel frightened in front of new people. Your mission statement should put into words what you need to build in your life both within yourself and in your environment that will result in comforting that side.

If your goal is to have fewer angry outbursts, for example, Nancy’s handling of the Mean is instructive. You need to comfort your anger from within by communicating with it, learning what that anger is about, respecting it, and beginning to accept it. The rational side of you that is not so angry has to communicate with your angry side, comfort it when it’s provoked, and help it respond to the situation more appropriately than with a temper tantrum. Externally to the best of your ability you want to reduce or eliminate environmental triggers of that angry side, whether it’s a nerve-jangling environment or exposure to abuse from a loved one, boss, or friend.

When strong emotions are triggered by essentially innocuous things, that can be a sign of some dissociated memory that needs to be addressed in therapy. The color red might trigger a memory of being raped, because you were wearing red on the day you were raped. Since you’ve developed the distorted thought that “red means I will be raped,” a therapist can help you disprove that distorted thought and challenge it effectively when you communicate with yourself about it. Nancy’s fear of the dark, Linda’s fear of intimacy, and Jean’s fear of abandonment are all examples of fears related to distorted thoughts that people learned how to correct in therapy

Cognitive distortion takes several forms, including overgeneralization, self-hatred, perfectionism, and gender negation.

Overgeneralization: This involves drawing a broad, sweeping conclusion from the particular abuse or trauma. Since Nancy’s father would steal into her bedroom at night and sexually abuse her, for example, she thought that she could never be safe in the dark. Having been raped by a man, Linda thought that all men were bad or that intimacy meant getting hurt. As a result of the violence and abuse in Jean’s childhood, she believed that no adult could be trusted, not even the adult part of herself.

Self-hatred: This results when the victim of abuse or trauma believes that his or her “bad” behavior caused that abuse. Survivors typically feel that they deserved the abuse. Nancy assumed that she was “a bad girl” because her mother mistreated her; Linda thought she deserved the rape because she disobeyed her mother; Jean thought she was a hateful person who deserved the cruelties of her childhood and should be punished forever when she accidentally killed a man.

Perfectionism: The assumption that “if only I had been perfect, I could have prevented this” is another form of distorted thinking. Nancy, Linda, and Jean were all given to painful ruminations about what they could have done differently to prevent the abuse or trauma. This habit persisted into adulthood and would not allow them to forgive themselves for any mistakes they made, predisposing them to depression and disowning of their own strengths and talents.

Gender negation: This is the belief that one sex is better than another and is the sole cause of ones problems. Meredith, a patient of mine who developed a male alternate personality, was taught by her mother that in order to lead an independent life you had to be a boy. Rather than believe that her mother was wrong, Meredith crippled her independence while she allowed her boy alter to enjoy what she thought she couldn’t do.

What causes these cognitive distortions? People develop this way of thinking about undeserved abuse or trauma in order to survive. In her book Betrayal Trauma: The Logic of Forgetting Childhood Abuse, Jennifer J. Frye coined the term “betrayal blindness” to explain how survivors develop amnesia for abuse as well as cognitive distortions about it. She defines betrayal blindness as “the lack of conscious awareness or memory of the betrayal” and says that it must occur under certain conditions of extensive betrayal of necessary trust. “The degree of betrayal by another person affects the victim’s cognitive encoding of the experience of the trauma. We are equipped to detect betrayal and escape it. However, for children who need their parents to survive, it is dangerous … to detect it and try to escape. It could mean more abuse and little or no love and care. It is more beneficial to be blind to the trauma.”

Part of that blindness is to believe that the abusing parent was right and the child was wrong. As abuse survivors get healthier, they can begin to acknowledge that bad things can indeed happen to good people—it was the way their parents attempted to show them love that was destructive; they did not deserve the abuse.

There are touches of this blindness in everyone. To some extent we all have to integrate the fact that our parents were supposed to love, us, yet they treated us at rimes in a manner that was not loving. Children of critical or rejecting parents or parents who saddled them with excessively high expectations may have had to blind themselves to this form of abuse, because if they saw it, they wouldn’t have had any parent who they thought was loving. Since they couldn’t survive without a parent, they had to believe that their parents did love them, but they weren’t good enough. As a result, their whole lives became a driven pursuit to disprove this cognitive distortion.

In a perverse way parental rejection is a spur toward accomplishment, but the price tag is often enormous anxiety. Milton, a physics professor, would get so frightened at times when he was teaching class that he was unable to talk. One time he actually fainted when he was going to give a presentation. In therapy he revealed that his extremely critical father was very physically abusive and would take him down to the cellar, where he would ritualistically have him walk around in a circle and beat him. Milton grew up with chronic terror that he carried around inside him into his fifties. He couldn’t say no to his superiors and had to take on more and more projects because he was afraid of disappointing them. Like Linda, who thought that all men were potential rapists, Milton believed that his students and his superiors were all his surrogate father, who would punish him brutally if he didn’t live up to their expectations.

A physician put Milton on medication for his anxiety as a teenager when he was a very successful athlete in school and suffered terrible anxiety on the field. From then on he medicated himself with barbiturates, and he entered psychotherapy for the first time only when his wife divorced him, complaining of his unavailability to her. In therapy I was able to reduce his medication and also the constant pressure he put on himself to be perfect. He reexamined his cognitive distortions and learned how to comfort the terrorized child within him. Another happy result was unexpected—his wife remarried him. Their relationship improved dramatically as Milton became able to share his feelings of anxiety and vulnerability with her.

Having internal dialogues with the hidden parts of oneself is an important part of communication, whether it’s done silently, out loud, or in writing. I find that writing letters is the most practical way to have the inner dialogues. The goal is to become aware of inner dialoguing and strengthen ongoing communication among the different parts. Jean’s letters to Jeanie and Jeanie’s to Cave Girl, a study in startling contrasts, set up a network of communication almost like a supportive message board or chat room on the Internet. Not only did it provide comfort for the different parts, but it also laid the groundwork for cooperating with each other in the next phase of treatment.

The letters are a way of building on and implementing the personalized mission statements and can be modeled after what you would write to a child of your own or an adopted child in need of comfort. You need to schedule regular time for these dialogues in your appointment book, making an appointment with yourself, in effect, rather than do them in a haphazard fashion. Like Linda, you may need to do your letter writing outside your home in a peaceful, quiet place safe from intrusion, such as a park or a library. Establishing a pattern of dialogues is absolutely essential; otherwise the hidden part of yourself from which you’ve disconnected—the part that is screaming or crying in fear or anger—will continue to cause problems in your life. A repetitive pattern of comforting dialoguing is what will eventually stop inappropriate fear or anger from erupting at work or jeopardizing, perhaps even breaking up, a close relationship.

Internal dialoguing is a powerful tool for clearing up cognitive distortions about love—“Love means getting hurt,” for one—that can keep you stuck in a destructive relationship or, like Linda, make you try to protect yourself by sabotaging a positive one. Your dialogue should help the frightened, lonely part of yourself distinguish the present from the past when you were forced to be with caretakers who abused you, because you were not mature enough to be independent. That needy, self-hating part needs to be told that it doesn’t deserve abuse and that it’s possible to invest in a supportive relationship and not get hurt. The more encouragement and hope you can give that part through your dialogues, the less likely you are to stay stuck.

Since the language of the “inner child” has become part of our culture, you can probably identify with this concept. You may not be disconnected from the feelings you had as a child or have them compartmentalized in a separate part of yourself, but you may not always be aware of how those feelings are influencing your behavior as an adult. Reconnecting yourself to those feelings and joining with them to bring about greater health are the tasks of cooperation. What are the feelings of your inner child? Is that child frightened, sad, alone? If those are the feelings that you’ve identified by communicating with that child, the adult part of you has to befriend that inner child now and help heal those feelings. The adult part that functions well in the world, that is capable and responsible and has talents, has to lift the burden from that child of harboring all those feelings of loneliness and isolation.

Cooperation occurs as a result of communication—discovering rituals or routines that you can do so that your inner child no longer feels so lonely, frightened, or sad. Jean, a talented artist, helped to ease Cave Girl’s isolation by drawing pictures of an older girl outside the cave to keep her company. You might develop some other creative, physical, or social routines that will help your scared inner child feel less lonely and afraid.

If you’ve identified a child part that is isolated by barriers of amnesia, the first step is to make that part aware that there are other parts, that the child isn’t alone. The feelings and memories held inside can come out and be shared. Sharing what’s inside them breaks the conspiracy of silence that has kept the parts disconnected from one another; now they can begin to cooperate with each other on a consistent basis. The adult part—some might say, the rational or professional part—begins to meld logic and reasoning with the emotional part, and the emotional part begins to emerge more freely in creativity or in the enrichment of personal relationships. It was this cooperation that helped Jean get her college degree, that enabled Linda to unfreeze the emotions that the rape trapped inside her shell, and that allowed Nancy to rediscover joy in her life through the exercise of her creative talents.

All of the preceding phases culminate in the development of an inner team. This connection of a person’s separate parts is the unity that ultimately cures the disconnection of dissociation.

For both dissociatives and nondissociatives connection between one’s intellectual side and one’s emotional side is a major issue. The corporate world, to some extent, promotes the compartmentalization of emotions, and work becomes the “safe haven” where people can disconnect from their emotions, as Linda did. People with this tendency function at a high level when they’re at work and can store their emotions in a box temporarily. When they’re not at work and their jack-in-the-box emotions spring out and confront them, they can fall apart.

With the inner teamwork that connection brings about, the intellectual side can share logic and reason with the emotional side that’s frozen in time as a traumatized child. The rational side can begin to challenge distorted thoughts and misperceptions that keep a dissociated part trapped in an automatic response. When Jean began to depersonalize on her walk in the woods, for example, her thinking self challenged the irrational assumption of the abandoned child within her that graduation meant the disappearance of the talents that got her through college.

The process of connection actually begins in the preliminary phase of identifying who the team players are. One might be a responsible professional; another, a self-destructive loose cannon; yet another, a lazy foot-dragger who doesn’t like to work; or there could be a stubborn, angry holdout who doesn’t want to join the team. Comforting and communicating with the players will bring about cooperation or sharing, and connection occurs when they begin functioning as a whole as opposed to individual players.

Uncontrollable mood swings are an example of what happens when the players are not working together as a team. Jean, Linda, and Nancy all spoke of rapid fluctuations in mood that they couldn’t control when some hidden part took center stage. People may be misdiagnosed as having bipolar or manic-depressive illness when in fact they may have dissociated parts that break loose with their own feelings and steal the spotlight from time to time instead of staying connected to the team.

One of the most effective ways of forging a connection between yourself and a hidden part or among the hidden parts themselves is to apply the skills you practice in the working world to this task. When Jean had trouble accessing Cave Girl—the part of herself that was still in shock from the violence and sexual abuse of her childhood—I asked her to apply the skills she used with her battered women clients to herself. She made an assessment of Cave Girl’s needs, identifying her withdrawal and silence as signs of depression. Of Cave Girl’s history, she said that whenever there was trouble at home she would retreat into her cave. The little girl had remained there throughout the rest of Jean’s life, frozen in time and unapproachable because of her distorted belief that she had to stay away from adults. Jean’s letters established a link between Cave Girl and Knowledge. As a trained counselor, she enlisted Knowledge’s help in approaching the little girl in the cave and getting her to join the team.

The natural by-product of successfully working through all of the phases of treatment—comforting and communicating with one’s separate parts and helping them to cooperate with each other and connect as a team—is integration. The more a person has experienced respecting and accepting the memories and feelings bound up in each part, the less need there is for the symptoms that maintained their disconnection, and they are all reduced:

Amnesia: With the flow and sharing of feelings and memories and skills and knowledge back and forth, amnesia has outlived its usefulness as a retaining wall and gradually diminishes.

Depersonalization: Once people can accept that the abuse or trauma happened to them, not to some stranger they’ve detached from themselves, they don’t have the same need for depersonalization when some trigger reminds them of the abuse or trauma. Like Linda, who doesn’t have to go outside her body anymore during intimacy with her fiancé and can allow herself to feel positive emotions, people who have inner teamwork are aware that this situation is different from past situations and feel safe now.

Derealization: People who are able to distinguish the present from the past and feel safe no longer need to disconnect from familiar people or their home environment. For an abused child, derealization was useful because mental detachment from the perpetrator was the only way that the child could escape. For an adult, having an internal system for preventing this automatic trauma response from going off inappropriately reduces disconnection from people who are close. Linda doesn’t have to disconnect from Ted, for example, and think of him as the rapist. He can be who he is, and she can acknowledge him and love him as he is today.

Identity confusion: When identity fragments within a person are connected, identity confusion is necessarily reduced. The reason people who dissociate have identity confusion isn’t that they lack an identity—it’s that they have many parts of their identity that are disconnected and attempting to have lives of their own. This is the inner struggle that dissociatives speak of so often. Once a person has connected with these inner parts and they’ve connected with each other in a supportive way, as opposed to a way that denies, disavows, or wants to get rid of, identity confusion is replaced by a feeling of unity. Moods stay on a more even keel and decision making doesn’t pull a person apart in a million different directions, because now there’s a team with a coordinator in charge.

Identity alteration: Seizing of control by different parts occurs much less frequently, if at all, as a result of inner teamwork. An exercise in inner teamwork before making an important decision or at some turning point in a person’s life is mentally calling a meeting of the different parts that have been identified and assigning the most functional part to chair the meeting. The chair asks the other parts to express their opinions so that everyone’s voice can be heard, acknowledged, and understood. In Jean’s case, for example, Knowledge might chair the meeting and have a discussion about dating after the divorce. Anger might want to get back into drinking and promiscuous sex. Sexuality’s healthy part might want to hold out for a relationship with a caring, responsible man who is not a substance abuser. Cave Girl might want to shrink from going out with anyone. Knowledge would make the ultimate decision, but at least everyone’s feelings would be made known and attended to so that the decision would not result in a mutiny by any particular part.

As functioning cooperation of this kind proceeds forward, all five dissociative symptoms further diminish or disappear entirely. Integration of the separate parts into a unified whole is a natural consequence, and the person whose identity was once a collection of estranged fragments is made whole. Alters are not “killed off,” as most people with DID initially fear; instead the dissociated memories, feelings, and behavior become integrated, eliminating the need for the five core dissociative symptoms. Internal struggle gives way to relative peace, and people who have suffered so much are now able to end abuse in their current life and build relationships with loving, supportive people.

Hypnosis can be useful for people with a dissociative disorder in a number of ways. As an adjunct to psychotherapy, hypnosis can help abuse survivors reduce guilt feelings associated with the abuse, as well as teach them how to identify, express, and nurture their dissociated feelings or hidden aspects of themselves.

One of the techniques I find particularly helpful with trauma or abuse survivors is Spiegel’s “split-screen” method, which teaches how to integrate one’s dissociated memories and feelings. The therapist instructs the patient to picture a traumatic memory on one side of a mental screen while visualizing positive or assertive responses to the trauma on the other. As a result, the patient comes away less weighted down by the trauma and is eventually able to have a more balanced view of it. For example, a woman suffering from posttraumatic symptoms following a violent attack might be instructed to project on her “screen” her courageous defense of her life whenever she was overwhelmed by intrusive memories of her brutal assault. This technique can also be used to recover pleasant memories from the past so that people can visualize “safe places” to go to during episodes of depersonalization or derealization.

Hypnosis by a clinician specifically trained in it can be a particularly effective way of reducing stress, anxiety, depression, and phobias, as well as managing pain. Because the full SCID-D evaluation usually elicits spontaneous memories of abuse, and traumatic memories also occur spontaneously throughout the treatment with the Four C’s, I generally do not use hypnosis for recovery of abuse memories. Having said that, I do believe hypnosis can be useful to someone with a dissociative disorder for a wide variety of associated symptoms.

Medication is a useful adjunct in the treatment of people with dissociative disorders. I often find that it temporarily alleviates such symptoms as severe anxiety or depression. Whether these symptoms are related to a coexisting disorder or are secondary to underlying dissociative symptoms, medication may provide some symptomatic relief.

Although there are few controlled studies of drug therapy for dissociative symptoms, many people with these symptoms find that medication relieves associated anxiety, depression, mood changes, and irritability. Antianxiety medications, used as needed, may be effective in reducing associated anxiety. There are many new antidepressants with minimal side effects that can reduce feelings of depression. Mood stabilizing and anticonvulsant drugs may reduce the severity of mood shifts. Hypnotic agents can help people suffering from insomnia. Stimulant medication, frequently used for coexisting ADHD, can help some dissociative people not only improve attention and memory, but have fewer shifts in moods. Medication may also help take the edge off the volatility in people with a dissociative problem, mitigating temper outbursts that occur with the uncontrolled emergence of angry feelings.

Finding a physician who understands dissociation is extremely important, because you will want to discuss the effect of a medication on all of your symptoms. People with a dissociative disorder may fluctuate in their need for medication, as well as in their sensitivity to it, depending upon which aspect of themselves is in control. If you haven’t been on medication before, it’s impossible to predict which medication will be most effective for you, so it helps to be flexible and see whether a particular medication prescribed by your physician works or not. Beware of using many different medications at the same time, though, because this often occurs when you are getting a different medication for each of your external symptoms, and in the meantime your dissociative symptoms are not receiving the specialized psychotherapy they need. Since people with dissociative disorders are not psychotic (out of touch with reality), antipsychotics should be used primarily for severe agitation that does not respond to antianxiety agents.

Medication for someone with an underlying dissociative syndrome should always be used in conjunction with psychotherapy; it is never a substitute for it. Pills can make the road less bumpy, but the long-term resolution of external symptoms like depression and anxiety depends upon getting specialized psychotherapy focused on treating internal dissociative symptoms.