The English word ‘follower’ is derived from the Old English word Folgian and the Old Norse Fylgja, meaning to accompany, help, or, ironically, to lead. These first three definitions are relatively positive:

1) An ordinary person who accepts the leadership of another.

2) Someone who travels behind or pursues another.

3) One who follows; a pursuer, an attendant, a disciple, a dependent associate, a retainer.

However, the negative images of ‘follower’ are more clearly visible in these definitions:

4) A person or algorithm that compensates for lack of sophistication or native stupidity by efficiently following some simple procedure shown to have been effective in the past.

5) A sweetheart, a Trollope.

6) (Steam engine) The removable flange of a piston.

7) The part of a machine that receives motion from another.

8) Gaelic: Surname ending in ‘agh’ or ‘augh’ = ‘follower of’ – Cavanagh = ‘follower of Kevin’.

Those readers familiar with the British comedian Harry Enfield’s character ‘Kevin’ – a teenage nightmare of sullenness and irresponsibility – will note the diminution of the role of follower in the light of the superordinate ‘leader’. Indeed, when listing the traits required by formal leaders, it is usual for a class to come up with any number of characteristics: charisma, energy, vision, confidence, tolerance, communication skills, ‘presence’, the ability to multi-task, listening skills, decisiveness, team-building, ‘distance’, strategic skills, and so on and so forth. No two lists constructed by leadership students, or leaders, ever seems to be the same, and no consensus exists as to which traits or characteristics or competencies are essential or optional. Indeed, the most interesting aspect of list-making is that by the time the list is complete, the only plausible description of the owner of such a skill base is ‘god’. Irrespective of whether the traits are contradictory, it is usually impossible for anyone to name leaders who have all these traits, at least to any significant degree; yet it seems clear that all these traits are necessary to a successful organization. Thus we are left with a paradox: the leaders who have all of these – the omniscient leaders – do not exist, but we seem to need them. Indeed, complaints about leaders and calls for more or better leadership occur on such a regular basis that one would be forgiven for assuming that there was a time when good leaders were ubiquitous. Sadly, a trawl through the leadership archives reveals no golden past, but nevertheless a pervasive yearning for such an era. An urban myth like this ‘romance of leadership’ – the era when heroic leaders were allegedly plentiful and solved all our problems – is not only misconceived but positively counter-productive because it sets up a model of leadership that few, if any of us, can ever match, and thus it inhibits the development of leadership, warts and all. It should be no surprise, then, to see, for example, the continuous re-advertising of vacancies for head teachers when the possibilities of success are either beyond the control of individuals or so clearly defined by comparative reference to Superman and Wonderwoman that only those who can walk on water need apply: not for these leaders the Roman warning: nemo sine vitio est (no-one is without fault).

The traditional solution to this kind of recruitment problem, or the perceived weakness of contemporary business chief executives or directors of public services or not-for-profit organizations, is to demand better recruitment criteria so that the ‘weak’ are selected out, leaving the ‘strong’ to save the day. But this is to reproduce the problem not to solve it. An alternative approach might be to start from where we are, not where we would like to be: with all leaders – because they are human – as flawed individuals, not all leaders as the embodiments of all that we merely mortal and imperfect followers would like them to be: perfect. The former approach resembles a ‘white elephant’ – in both dictionary definitions: as a mythical beast that is itself a deity, and as an expensive and foolhardy endeavour. Indeed, in Thai history, the king would give an albino elephant to his least favoured noble because the special dietary and religious requirements would ruin the noble.

The white elephant is also a manifestation of Plato’s approach to leadership, for to him the most important question was ‘Who should lead us?’ The answer, of course, was the wisest amongst us: the individual with the greatest knowledge, skill, power, resources of all kinds. This kind of approach echoes our current search criteria for omniscient leaders and leads us unerringly to select charismatics, larger-than-life characters, and personalities whose magnetic charm, astute vision, and personal forcefulness will displace all the bland and miserable failures that we have previously recruited to that position – though strangely enough using precisely the same selection criteria. Unless the new leaders are indeed Platonic philosopher-kings, endowed with extraordinary wisdom, they will surely fail sooner or later, and then the whole circus will start again, probably with the same result.

Of course, for Plato, it was more than likely that the leaders would be men; after all, Greek women were not even citizens of their own city-states, though Plato did admit that it was theoretically possible that a woman might have all the natural requirements of leadership. Since Plato’s time, assumptions about the role of gender in leadership have varied enormously, even if the presence of women as leaders has proved remarkably limited and remarkably stable (see Chapter 5).

An alternative approach is to start from the inherent weakness of leaders and work to inhibit and restrain this, rather than to assume it will not occur. Karl Popper provides a firmer foundation for this in his assumption that, just as we can only disprove rather than prove scientific theories, so we should adopt mechanisms that inhibit leaders rather than surrender ourselves to them. For Popper, democracy was an institutional mechanism for deselecting leaders, rather than a benefit in and of itself, and, even though there are precious few democratic systems operating within non-political organizations, similar processes ought to be replicable elsewhere. Otherwise, although omniscient leaders are a figment of irresponsible followers’ minds and utopian recruiters’ fervid imaginations, when subordinates question their leader’s direction or skill these (in)subordinates are usually replaced by those more aligned with the current strategic thinking’ – otherwise known as ‘yes-people’. In turn, such subordinates become transformed into irresponsible followers whose advice to their leader is often limited to destructive consent: they may know that their leader is wrong, but there are all kinds of reasons not to say as much, hence they consent to the destruction of their own leader and possibly their own organization too.

Popper’s warnings about leaders, however, suggest that it is the responsibility of followers to inhibit leaders’ errors and to remain as constructive dissenters, helping the organization achieve its goals but not allowing any leaders to undermine this. Thus constructive dissenters attribute the assumptions of Socratic ignorance rather than Platonic knowledge to their leaders: they know that nobody is omniscient and act accordingly.

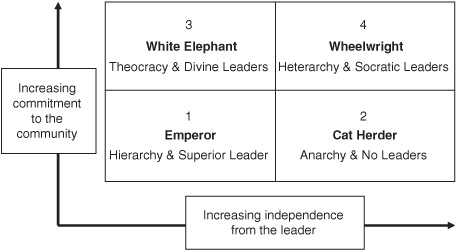

Of course, for this to work, subordinates need to remain committed to the goals of the community or organization (and of course, there are often good reasons not be committed to an organization that has no reciprocal commitment to you) while simultaneously retaining their spirit of independence from the whims of their leaders. It is this paradoxical combination of commitment and independence that provides the most fertile ground for responsible followers. Figure 19 outlines the possible combinations of this mix of commitment and independence. Again, this is for illustrative purposes and generates a series of Weberian ‘ideal types’ that are neither ‘ideal’ in any normative sense nor ‘typical’ in any universal sense. On the contrary, these types are for heuristic purposes, designed to flag up and magnify the extreme consequences of theoretically polar positions.

19. Leadership, followership, commitment, and independence

Despite these reservations, Box 1 – the hierarchy – probably contains the most typical form of relationship between leaders and followers, wherein a conventional hierarchy functions under a leader deemed to be superior to his or her followers by dint of the conducive personal qualities of intelligence, vision, charisma, and so on and so forth, and thus to be responsible for solving all the problems of the organization. Such imperial ambitions resonate with the label for this form of leader: the emperor. In turn, that generates followers who are only marginally committed to the organization’s goals – often because these are reduced to the personal goals of the leader – and hence the followers remain literally ‘irresponsible’ through the destructive consent that is associated with the absence of responsibility.

Box 2 is rooted in a similar level of disinterest in the community but, combined with an increase in the level of independence from the leader, the consequence is a formal ‘anarchy’ – without leadership – and without the community that supporters of anarchism suggest would automatically flow from the absence of individual leaders. The result is a leader who resembles a ‘herder of cats’ – an impossible task. We will return to anarchism in the final chapter.

Box 3 – the theocracy – generates that community spirit in buckets but only because the leader is deemed to be a deity, a divine leader whose disciple followers are compelled to obey through religious requirement: the white elephant described above. That consent remains constructive if – and only if – the leader is indeed divine, a god whose omniscience and omnipotence are unquestionably present. However, it is clear that although many charismatics generate cults that would ostensibly sit within this category, the consent often becomes destructive because the leader is in fact a false god, misleading rather than leading his or her disciples.

The final category, Box 4 – the heterarchy – denotes an organization in which the leaders recognize their own limitations, in the fashion of Socrates, and thus leadership is distributed according to the perceived requirements of space and time (a rowing squad is a good example of a heterarchy in which the leadership switches between the cox, the captain, the stroke, and the coach depending on the situation). That recognition of the limits of any individual leader generates a requirement for responsible followers to compensate for these limits, which is best served through constructive dissent, in which followers are willing to dissent from their leader if the latter is deemed to be acting against the interests of the community.

Perhaps an ancient Chinese story, retold by Phil Jackson, coach of the phenomenally successful Chicago Bulls basketball team, makes this point rather more emphatically. In the 3rd century BC, the Chinese Emperor Liu Bang celebrated his consolidation of China with a banquet where he sat surrounded by his nobles and military and political experts. Since Liu Bang was neither noble by birth nor an expert in military or political affairs, one of the guests asked one of the military experts, Chen Cen, why Liu Bang was the emperor. Chen Cen’s response was to ask the questioner a question in return: ‘What determines the strength of a wheel?’ The guest suggested the strength of the spokes, but Chen Cen countered that: ‘Two sets of spokes of identical strength did not necessarily make wheels of identical strength. On the contrary, the strength was also affected by the spaces between the spokes, and determining the spaces was the true art of the wheelwright.’ Thus, while the spokes represent the collective resources necessary to an organization’s success – and the resources that the leader lacks – the spaces represent the autonomy for followers to grow into leaders themselves.

In sum, holding together the diversity of talents necessary for organizational success is what distinguishes a successful from an unsuccessful leader: leaders don’t need to be perfect but, on the contrary, they do have to recognize that the limits of their knowledge and power will ultimately doom them to failure unless they rely upon their subordinate leaders and followers to compensate for their own ignorance and impotence. Real white elephants – albinos – do exist, but they are so rare as to be irrelevant for those who are looking for them to drag us out of the organizational mud; far better to find a good wheelwright and start the organizational wheel moving. In effect, leadership is the property and consequence of a community rather than the property and consequence of an individual leader. Moreover, whereas white elephants are born, wheelwrights are made. In fact, the analogy is useful in distinguishing between the learning pedagogies of both, for while those who believe themselves born to rule need no teachers or advisers, but merely supplicant followers, those who are wheelwrights have to serve an apprenticeship in which they are taught how to make the wheel and in which trial and error play a significant role.

Another resolution of this paradox is that the focus should be shifted from the leader to leader ship – such that, as a social phenomenon, the leadership characteristics may well be present within the leadership team or the followers even if no individual possesses them all. Thus it is the crew of the metaphorical ‘ship’, not the literal ship’s ‘captain’, that has the requirements to construct and maintain an organization; hence the need to put the ‘ship’ back into ‘the leadership’. In other words, rather than leadership being restricted to the gods, it might instead be associated with the opposite. As Arundhati Roy remarks about her own novel, ‘To me the god of small things is the inversion of God. God’s a big thing and God’s in control.’ Here, I want to suggest that leadership is better configured as the ‘god of Small Things’.

The Big Idea, then, is that there isn’t one; there are only lots of small actions taken by followers that combine to make a difference. This is not the same as saying that small actions operate as ‘tipping points’, though they might, but rather that big things are the consequence of an accumulation of small things. An organization is not an oil tanker which goes where the captain steers it, but a living and disparate organism, a network of individuals – its direction and speed are thus a consequence of many small decisions and acts. Or, as William Lowndes (1652–1724), Auditor of the Land Revenue under Queen Anne, suggested, ‘Take care of the pence and the pounds will take care of themselves.’ This has been liberally translated as ‘Take care of the small things and the big things will take care of themselves’, but the important thing here is to note the shift from individual heroes to multiple heroics. This doesn’t mean that CEOs, head teachers, chief constables, army generals, and so on are irrelevant; their roles are critical – as we shall see in the final chapter – indeed, their own preparation for the ‘big’ decision that may derive from the accumulation of many small acts and decisions.

Another way of putting this is that the traditional focus of many leadership studies – the decision-making actions of individual leaders – is better configured as the consequence of ‘sense-making’ activities by organizational members. As Weick suggests, what counts as ‘reality’ is a collective and ongoing accomplishment as people try to make sense of the ‘mess of potage’ that surrounds them, rather than the consequence of rational decision-making by individual leaders. That is not to say that sense-making is a democratic activity, because there are always some people more involved in sense-making than others, and these ‘leaders’ are those ‘bricoleurs’ – people who make sense from the variegated materials with which they are faced and manage to construct a novel solution to a specific problem from this assembly of materials. Because of this, success and failure are often dependent upon small decisions and small acts – both by leaders, and by ‘followers’ who also ‘lead’. This implies not that we should abandon Plato’s question, ‘Who should rule us?’, but focus more on Popper’s question, ‘How can we stop our rulers ruining us?’ In effect, we cannot secure omniscient leaders, but because we concentrate on the selection mechanism, those who become formal leaders often assume they are omniscient and are therefore very likely to make mistakes that may affect all of us mere followers and undermine our organizations.

Take, for example, the infamous British Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon whose actions on 22 June 1893 off the coast of Syria caused the loss of his own flagship, the Victoria, after he insisted that the British fleet, then split into two columns, turn towards each other in insufficient space. Despite being warned by several subordinates that the operation was impossible, Tryon insisted on its execution and 358 sailors were drowned – including Tryon. At the subsequent courts martial of Rear Admiral Markham on the Camperdown that rammed the Victoria, he was asked, ‘if he knew it was wrong why did he comply?’ ‘I thought’ responded Markham, ‘Admiral Tryon must have some trick up his sleeve.’ The court found Tryon to blame but accepted that it ‘would be fatal for the Navy to encourage subordinates to question superordinates’. Thus, to misquote Burke, it only takes the good follower to do nothing for leadership to fail.

Nor are attributions of omniscience limited to national military or political leaders alone. For example, when the Air Florida 90 (‘Palm 90’) flight crashed on 13 January 1982 in poor weather conditions, it is apparent from the conversation between Captain Larry Wheaton and the 1st Officer Roger Pettit that the latter was unconvinced that the plane was ready for lift-off, yet his failure to stop Wheaton from going ahead inadvertently led to the crash. Precisely the same thing occurred in the Tenerife air crash where the co-pilot thought that there was a problem but failed to prevent the pilot from taking off in a dangerous situation because his warnings were too ‘mitigated’ (another plane was taking off directly in front of them and, unbeknown to the co-pilot, his own pilot did not have permission to take off). In fact, the British Royal Air Force has a ‘failsafe’ mechanism within their Crew Resource Management System which effectively allows any member of a plane’s crew – at any rank – to demand the captain abandons the take-off or landing, in the same way that the British Army and Navy have ‘stop-fire’ systems that allow juniors to override their seniors when live firing is underway and the junior recognizes a danger that their senior cannot see.

Alfred Sloan, president of General Motors, faced a similar problem with his board but was able to recognize the manifestations of destructive consent:

‘Gentlemen, I take it we are all in complete agreement on the decision here?’

[Consensus of nodding heads.]

‘Then I propose we postpone further discussion of this matter until our next meeting to give ourselves time to develop disagreement and perhaps gain some understanding of what the decision is all about.’

Three hundred years earlier, the Japanese samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo recalled an equivalent:

Last year at a great conference there was a certain man who explained his dissenting opinion and said that he was resolved to kill the conference leader if it was not accepted. This motion was passed. After the procedures were over the man said, ‘Their assent came quickly. I think that they are too weak and unreliable to be counsellors to the master.’

What can be done about this problem? Clearly the provision of honest and timely advice to leaders – constructive dissent -provides an appropriate solution, but it is equally clear, first that leaders tend to discourage this by recruiting and appointing subordinates who are ‘more aligned with the official line’ – that usually means sycophants who provide destructive consent. Moreover, leaders’ unwillingness to admit to mistakes reinforces followers’ attribution of omniscience. Historically, only the royal ‘fool’, or court jester, could provide constructive dissent and survive, primarily because the advice was wrapped up in humour and therefore could be publicly dismissed by the monarch, even if privately he or she could then reconsider it rather more carefully. There is, perhaps, no better example of the difficulty and importance of this role than the Fool in Shakespeare’s King Lear.

Lear, having given away his kingdom to his daughters in a show of bravado and omnipotence, is warned first by his loyal follower, Kent, that the action is foolhardy, but Kent is exiled for his honesty. Then the Fool attempts the same advice but does so through a series of riddles that, unfortunately, Lear begins to understand only when it is too late:

Fool: That lord that counsell’d thee

To give away thy land,

Come place him here by me,

Do thou for him stand:

The sweet and bitter fool

Will presently appear;

The one in motley here,

The other out there

Lear: Dost thou call me fool, boy?

Fool: All thy other titles thou hast given away; that thou wast born with.

(King Lear, Act 1, Scene 1, 154–65)

It is possible to recreate the role of honest advisor played by Shakespeare’s Fool without the ‘motley’ clothes and perhaps with more success, either by leaders relying on one or more individuals whose position cannot be threatened by the advice proffered, and it may also be possible to institutionalize the role by requiring all members of a decision-making body to enact the role of ‘devil’s advocate’ in turn. In this way, the advice is required by the role and not derived from the individual, and hence should provide some degree of protection from leaders annoyed by the ‘helpful’ but perhaps embarrassing advice of their subordinates.

Nevertheless, the contested nature of charisma – both in terms of its origins and existence – leaves unresolved the yearning for perfection in leaders that perhaps also reflects our collective dissatisfaction with the lives of unacknowledged followers – the gods of small things. As Albert Schweitzer in his autobiography Out of My Life and Thought remarked:

Of all the will toward the ideal in mankind only a small part can manifest itself in public action. All the rest of this force must be content with small and obscure deeds. The sum of these, however, is a thousand times stronger than the acts of those who receive wide public recognition. The latter, compared to the former, are like the foam on the waves of a deep ocean.

This is a critical assault upon the idea that leadership can be reduced to the personality and behaviour of the individual leader and implies that we should recognize that organizational achievements are just that – achievements of the entire organization rather than merely the consequence of a single heroic leader. Yet, although it is collective leaders and collective followers who move the wheel of history along, it is often their formal or more Machiavellian individual leaders who claim the responsibility, leaving most people to sink unacknowledged by history, nameless but not pointless. George Eliot makes this poignantly clear at the end of her novel Middlemarch in her description of Dorothea:

Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Leaders are important – and we shall consider their role in the final chapter – but there are whole rafts of other elements that are also important, and it is often these that make the difference between success and failure. Perhaps the least understood or evaluated of these other elements is the role of the followers, without whom leaders cannot exist. But this does not mean that we can abandon the individual leader and rely upon the spontaneous leadership of the collective – as we shall see in the final chapter.