Cut doors and windows for a room;

It is the holes which make it useful.

Therefore profit comes from what is there;

Usefulness from what is not there.

(Tao Te Ching, Verse 11)

In Chapter 7, I suggested that we needed to put the ‘ship’ back into leadership if we were to understand how leadership actually worked – in effect, we needed to bring the collective back into leadership. But there is an equivalent danger of eliminating leaders from collaborative or distributive leadership to the point where – if we only just collaborated with each other more – we could resolve the world’s problems collectively and without recourse to leaders. In this final chapter, I want to suggest that this is as mistaken as the assumption that leaders don’t need to think about followers, but in this case I want to put the leader back into leadership.

In an era of global problems – whether they are financial, environmental, religious, social, or political – the calls for post-heroic leadership have come ever thicker. The alternatives to heroic leadership (for there are several varieties) imply that leadership is unnecessary, or that it can be distributed equally amongst the collective, or that once the cause of conflict – whether that is private property, as Marx suggested, or religion – is removed, it becomes unnecessary, or that heroic leadership is the consequence rather than the cause of organization. In attempting to escape from the clutches of heroic leadership, we now seem enthralled by its apparent opposite – distributed leadership: in this post-heroic era we will all be leaders so that none are.

The idea that leadership could be an unnecessary aspect of society or organization, or that it should be ‘distributed’, either moderately (so that leadership is shared) or radically (so that, because everyone is a leader, no-one is), has long antecedents. In practice, many hunter-gatherer societies – such as the Hadza of Tanzania – operate without a single formal leader, and leadership tasks are distributed so that any individual can ‘lead’ a hunt or suggest a move to new territory and so on. Many such hunter-gatherer societies adopt formal leadership systems only when coerced by colonizing forces – as did many American Indian tribes, for example. But even those cultures without institutionalized leaders still retain elements of leadership: hence the Comanche, while embodying the most mobile and anti-authoritarian culture of all American Indians, followed temporary leaders when war, hunting, or their religion required. Similarly, the Nuer followed what Evans-Pritchard described as a ‘segmentary’ system – a mobile mix of family-based groups that would constantly align and realign themselves to other family groups, but without institutional leadership.

Such limited manifestations of leadership are even rarer in the West, and as we have moved from hunter-gatherer societies through the so-called ‘warlord era’ (roughly from the end of the last ice age to the industrial era), associated with the development of settled agriculture to the large-scale industrial societies, the form of leadership has apparently changed to the point where institutional and administrative forms of democracy and bureaucracy have displaced the warlord with temporary networks of political, business, cultural, and military leaders that many would argue mirrored the alpha-males of the warlord era. However, in the 21st century, when wicked problems appear to prevail, the world might be better served through collaborative leadership that displaces the 20th-century warlords with a governance system more suited to those who conventionally suffer from the acts of warlords.

The link between warlords (including absolute monarchies and political dictatorships) and their various supportive priesthoods has often been used to defend leadership on the basis of its sacred link with a god of some variety. Whether that link is the ‘divine right’ of monarchs, or the representation of secular leaders as demi-gods in their own right, or even the attribution of divine status by followers to their leaders, it is clear that leadership has some connection to the realm of the sacred. But how important is the connection, and what does it imply for redistributing authority away from formal and individual leaders?

It might have been thought that the secularization of the West which began with the Enlightenment would have undermined the sacred aspect of leadership through the separation of the state from the church. Nietzsche certainly suggested in The Gay Science that the metaphorical death of god might act as a release on humanity, providing the open sea as a canvas upon which to paint new beginnings, so one might conclude that the secularization of society could initiate a new approach to leadership bereft of its adulation of god-like leaders. But Nietzsche had other questions to ask:

God is dead. God remains dead. And we have killed him. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

(1991, section 125)

The return of religious fundamentalism of all varieties has rudely shattered the assumption that the metaphorical god is dead, but for Karl Popper this question could only be answered with another question: if god is dead – then ‘Who is in his place?’ This reconstruction – or perhaps ‘reconsecration’ is a better word – of the leader implies that perhaps leadership is inescapably locked into the realm of the sacred, and if it is, does that have implications for a radical redistribution of authority?

The issue appears to be less about the sacred nature of leadership -because if there is a way of living without leadership, then its sacred nature cannot be a pre-requisite for organization – and more about how social life can be coordinated. Yet ironically, the constant refrain in ‘alternative’ communities is one usually enshrined in the sacred nature of the community or the ‘sanctity’ of freedom. The form of the sacred may well be transformed and be infinitely open to interpretation – but it remains quintessentially sacred. In effect, the denial that anyone else should have authority over oneself – because that would undermine one’s integrity -generates a resistant sanctity in the sacredness of the individual or that of the community. Or, as Jo Freeman (one of the leading American feminists of the 1970s) put it, the consequence of structurelessness is not freedom from structure or authority (patriarchal or any other variety) but a shift from formal to informal structure – with all the potential for tyranny that informal groups and militant sects can muster. Freeman suggested that democratic structuring would be preferable to structurelessness because at least then the structure is more transparent and open to change. But again, the delegation and distribution of authority and the rotation of tasks requires all participants to be willing and able to make significant contributions in terms of time and effort. For some, that effort may be displaced: for instance, Fletcher suggests that the new post-heroic models, despite being ascribed as more feminine models, are still essentially rooted in masculine organizations where collaboration, relationship-building, and humility are regarded as symptoms of weakness not leadership. Indeed, the top echelons of organizations remain predominantly in the hands of men, so that post-heroic models of leadership are simply models of post-heroic heroes.

For some, the issue is not so much ‘leadership’, but what kind of ‘leadership’, and in particular those aspects of leadership relevant to the development of distributed leadership in which leadership resides in the collective. Raelin attempts to contrast the distributed or leaderful organization with the traditional organization by suggesting that in leaderful organizations leadership is concurrent and collective rather than serial and individual – lots of people are engaged in it rather than just those in formal positions; that leadership is collaborative rather than controlling; that leadership is compassionate rather than dispassionate; and that this generates a community rather than simply an organization. The apparent consequences of distributive leadership, according to Gronn, are threefold: first, ‘concertive action’ – or leadership synergy in which the whole of distributive leadership is greater than the sum of its parts; second, the boundaries of leadership become more porous, encouraging many more members of the community to participate in leading their organizations; third, it encourages a reconsideration of what counts as expertise within organizations and expands the degree of knowledge available to the community. In sum, leadership becomes not a property of the formal individual leader, but an emergent property of the group, network, or community.

Without wishing to defend ‘heroic leadership’, there is a conundrum here: if heroic leaders have been with us for aeons – and have been responsible for most of the tragedies that have befallen the human race since records began – why have we only just recognized their fallibility? And if we have known about their fallibility for as long as they have existed, why has no effective long-term, and large-scale, alternative been developed? In other words, is the hypothetical post-heroic leadership alternative really a viable alternative?

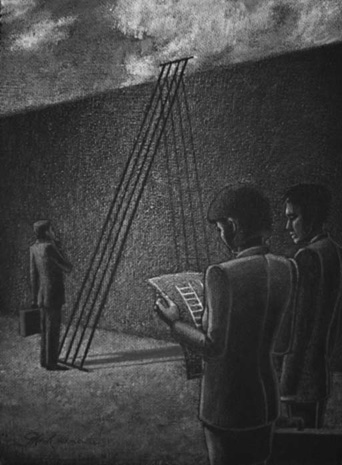

Of course, this may be a very Western representation, and it clearly is the case that notions of leadership and concepts of the sacred are often radically different in different cultures – a topic too broad to be covered in this book. Indeed, what counts as leadership and the sacred in the USA often seems to be markedly different from their equivalents in the UK. Satirizing, nay lampooning, religious leaders may be de rigueur in many North European societies, but it obviously is not in either Iran or the USA. My concern, then, is not to suggest that either Western or British accounts of the link between the sacred and leadership are valid everywhere, but that there probably is a significant link between the two phenomena in different cultures, though the specific nature of the concepts and the links may be dramatically different across the globe. I will also suggest that the sacred is less the elephant in the room – the thing which dare not be mentioned – and more the room itself – the space within which leadership works. That is one reason why it is seldom raised – because it forms the framework within which leadership works.

The etymology of the term ‘sacred’ offers clues as to its nature without providing an explanation for it (Collins English Dictionary, 2005; Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, 1966). ‘Sacred’ comes from the Latin sacer meaning ‘sacred or holy or untouchable’, which itself came from the Latin sancire – ‘consecrate, dedicated to a religious purpose, reverenced as holy, secured against violation; to set apart’. Thus one element of the sacred lies in the distance or difference between the sacred and the profane. ‘Sacrilege’ – which comes from a Latin compound meaning ‘to steal holy things’ – transcends this boundary and pollutes the sacred. Indeed, the original meaning of ‘hierarchy’ was ‘holy sovereignty’: arkhos means ‘sovereignty or ruler’ and hierós means ‘holy or divine’ in the original Greek. Hierarkhíã was a sacral ranking, and thus the concept of ‘hierarchy’ is the sacred organizational space that facilitates god’s (or the priesthood’s) leadership. The Latin sacerdos means ‘priest’, and ‘sacrifice’ is derived from a Latin compound meaning ‘to make holy’, thus a second element of the sacred relates to the essential issue of sacrifice by those deemed closest to god – the priesthood: sacrifice is what makes something sacred – it performs leadership. Finally, ‘sacred’ refers to an attitude of reverence or ‘awe’, ‘a silence in the presence of the divine’. That silence seems to imply a silencing of the fears of believers as their god, or their god’s representatives, displace any existential anxieties, or in the Ancient Greek version, where the gods themselves played out the existential fears of mere mortals.

The etymology, then, suggests that the sacred aspect of leadership involves at least three qualities that pertain to the debate about leadership: ‘setting apart’ – the division between the holy and the profane; ‘sacrifice’ – the act that makes something holy; and ‘silencing’ by the religious or secular leaders of both followers’ fears and their dissent. Let us proceed briefly through this sacred grove of leadership before considering whether the sacred aspect is necessary and whether this has implications for working without leaders.

There is a long historical association between separation, proximity, and leadership. Take, for instance, the ‘little touch of Harry in the night’ that settles the English army of Shakespeare’s Henry V on the eve of Agincourt: this is considered significant precisely because followers so rarely get close to their leaders, let alone touch them. Monarchs, of course, commonly legitimated their rule through their links with god, and were therefore only responsible to god, so the assumption that their touch was sacred followed logically from the assumption that their whole being was sacred. These differences – the separation between the prof ane and the sacred – must be protected through monitoring of the boundary, and this may be achieved through preventing direct or unmediated access to the leader, or by the leader displaying specific clothing or other signs of difference. Of course, different cultures embody different distancing mechanisms, indeed different notions of acceptable distance, but some distancing – whether symbolic or material, and whether we are looking at task-oriented or people-oriented leadership – appears universal. For example, Hitler was noted for the plainness of his uniform, which differentiated him from other Nazi leaders in their heavily bemedalled and ostentatious clothes, but connected him to the common ‘people’ -though he could never be ‘one of them’.

The idea that leadership involves some mechanism of ‘distance’ between leader and follower is commonplace, especially the belief that proximate leaders are significantly better than distant leaders. In contrast, Machiavelli was keen to note that distance was a useful device for preventing followers from perceiving the ‘warts-and-all’ nature of leaders, for:

men in general judge more by their eyes than their hands; for everyone can see but few can feel. Everyone sees what you seem to be, few touch upon what you are, and those few dare not to contradict the opinion of the many who have the majesty of the state to defend them.

This has profound implications for those seeking to become leaders because the ability to control distance, especially to keep others at bay and yourself beyond their gaze, is critical to maintaining the mystique of leadership – as the Wizard of Oz found to his cost after the veil hiding his ‘ordinary’ nature was drawn away.

Distancing is also a device for facilitating the execution both of distasteful but necessary tasks by leaders and of generating the space to see the patterns that are all but invisible when very close to followers or the action – an issue Heifetz and Linsky capture well with their metaphor of ‘getting on the balcony’ to see the patterns created by the (organization’s) dancers.

While distancing may have been critical to leadership in previous times, the contemporary move in Western democracies, under the glare of 24-hour mass media at least, is to generate an image of leadership that minimizes social distance – hence Tony Blair would speak to the media outside his official residence in Downing Street wearing a pullover and holding a mug of tea – as if he were ‘one of us’ – though few of us would do that in front of the world’s press, and even fewer would call him ‘Tony’ to his face, whether we were friend or foe.

Nevertheless, Collinson suggests that the over-concentration on charismatic leaders overlooks the possibility that distance also provides significant opportunities for followers to ‘construct alternative, more oppositional identities and workplace countercultures that express scepticism about leaders and their distance from followers’. This is particularly apparent in the way that humour is used to distance followers from leaders, though again that can also encourage followers to acquiesce to the leadership of their leaders by a functional venting of their frustration rather than organizing their resistance.

The separation of leaders and followers also throws into stark relief the nature of inequality that underpins leadership, despite all the obfuscation about empowerment, distributed, democratic, or participative leadership. Indeed, Harter and colleagues suggest that this inegalitarianism is both legitimate and necessary, generating mutually beneficial inequality – providing certain safeguards are maintained. That the inequality at the heart of leadership needs to be legitimated – while equality is often regarded as legitimate in and through itself – might also explain why we seem to have a sacred regard for leadership – because it has to be treated as sacred to maintain its legitimacy.

This might also account for the degree of violence used against those with the temerity to challenge leadership overtly considered sacred, for the sacred can only be maintained if those who act to abuse it – those who commit sacrilege – are severely treated. Hence the gruesome execution meted out to the would-be regicide Damiens as recounted at the beginning of Foucault’s book Discipline and Punish. Sacrilege – the transcendence of the separation of the sacred from the profane; indeed, the pollution of the sacred – plays a critical role in the construction of leadership as well as being perceived as an assault upon it. For instance, Gorbachev’s criticisms of the Soviet Communist Party – his sacrilege – opened the floodgates that eventually sank the Soviet Union. Until his very public verbal assaults, few had dared to speak ill of the Party, but once he had given permission for others to engage in critique the Communist Party’s sacred integrity was irretrievably damaged. The same might be said of Tony Blair, whose denunciation of Clause IV (common ownership of the means of production, distribution, and exchange) in the Labour Party Conference of 1994 began the process of transforming the Labour Party to New Labour.

So a critical aspect of the sacred is that it necessarily involves a division between the sacred and the profane; there must be a distance between the two for the division to make sense, though of course the precise nature of the division is very flexible and likely to vary with different cultures. In fact, ‘difference’, rather than ‘distance’, might be a better way of comprehending the importance of distinction here. The physical or symbolic distance between leader and led may be great or small, but the difference between the two might be the key to success. In other words, might it be that where difference is removed, so that there are no leaders because all – or none – are leaders, there is no leadership? This is not to suggest that some organizational forms under certain circumstances cannot persist without leadership, but rather that leadership cannot survive without difference. Difference is a performative element of leadership, not a trivial embellishment of status.

The use of sacrifice in ancient societies is, of course, as commonplace as it is offensive to many contemporary eyes. While the Aztecs were sacrificing hundreds to their sun god and wearing the skins of their victims, Romans, Ancient Greeks, Celts, Carthaginians, Africans, Asians, and seemingly everyone else, were similarly soaked in human and animal blood to appease their gods, to protect the tribe, to ensure fertility or food supplies, to ensure the dominant tribe did not devastate your land or just to ensure your subjugated followers were kept in line. The Ancient Greek tradition of the pharmakos involved the ritualized scapegoating -expulsion or perhaps execution – of human victims by a community under threat from war or famine.

The ritual necessity of scapegoating forms an essential core of René Girard’s work and relates to the role of mimesis – the desire of all humans to imitate each other. This appropriation of others eventually leads to expropriation of others, an inevitable rivalry, an aggressive response, and a consequential generalized social violence. Girard suggests that across thousands of years, humans have managed to contain this ‘natural’ propensity to social violence by the sacrifice of individuals. In effect, the primal murder of scapegoats cleanses the community of greater social violence and generates a temporary peace – until the next cycle of mimetic rivalry and violent contagion required the next scapegoat. Thus the only solution to the Hobbesian ‘war of all against all’ was to narrow the focus down to the ‘war of all against one’. And Kristeva is surely right, very often it is women who are sacrificed to maintain the leadership of men – as so-called ‘honour killings’, for example, usually imply. Often, of course, the sacrificer becomes the sacrificed, most notably if we think of monarchs, such as Charles I of England and Louis XVI of France, but also some leaders whose very policy had been to overthrow such people – for example, Robespierre, or even Cromwell, who died of natural causes but was then disinterred and his body hung in chains while his head was displayed on a pole outside Westminster.

But we do not need to restrict ourselves to physical death to admit that sacrifice still plays a prominent part in leadership, especially in scapegoating of leaders or followers: democratic regimes frequently scapegoat their political leaders for policy failures, and CEOs frequently scapegoat a section of their own workforce when problems emerge or they themselves are scapegoated by the shareholders. Scapegoats that escape the ultimate sacrifice have traditionally been exiled, shunned, tarred and feathered, had their heads shorn, been demoted, sacked, or imprisoned, and many of these actions have been preceded by a show trial of some form, so that the sacrifice encompasses the widest possible public arena: the sacrifice must not just be done but be seen to be done. Again, non-blood sacrifice may also be the self-sacrifice of the leader. For example, Ford’s CEO in 2009, Alan Mulally, promised to run Ford for $1 a year if Congress would provide a financial bailout in 2009.

Of course, we all make sacrifices all the time – we sacrifice a lunch break to clear the email backlog, we sacrifice a lie-in on Sunday morning to get the grass cut, and so on, but the kind of sacrifice I am referring to here is for the collective good – however that is defined. Thus our mundane personal sacrifices that do not involve any effect upon the relationship between leaders and followers are not included in this category. Forgoing a cream cake for the good of your health is not the same as sacrificing the baker to improve collective morale in the bakery. And sacrifice is not an unfortunate and embarrassing aspect of some immoral or psychopathic dictator, but an essential mechanism for the performance of all forms of leadership. Sacrifice constructs the sacred space without which leadership cannot occur.

The sacred aspect of silence involves several principles beyond that of providing space for reflection: the silencing of opposition and the silencing of anxiety. The former is a role that is well documented (for example, by Collinson and Ackroyd, listed in the further reading section) and need not delay us here.

In principle, the notion that leadership is related to the sacred runs directly counter to existentialism, which operates from the opposite end of the philosophical spectrum: we are not the result of god’s plan but our own conscious free acts. However, this approach implies that the anxiety generated by the uncertainty and purposelessness of existence is precisely why the burden of responsibility is so great. Were we to believe in fate ordained by a god, then the burden of responsibility is lifted from our shoulders, since all that we do is already inscribed by whichever god is purported to be responsible. But if all that we do is a result of free will floating without moral precept derived from god, then we appear to be both responsible for our decisions and cast adrift from any foundational moral compass with which to make these decisions. Absoluteness and absolution are the twin promises of this fabled leadership land and this double Faustian pact. For leaders, the pact exchanges privilege and power now in exchange for sacrifice later; for followers, the pact secures a security blanket against ‘bad faith’ – Jean-Paul Sartre’s ‘exposure of freedom’ that underlies even the most desperate decision between two alternative evils. In effect, leadership silences the anxiety of followers.

Erich Fromm suggested that the fear of freedom was also an essential explanation for our almost compulsive submission to authority. For Fromm, modernity had uprooted people from communal relationships with others, and it was this intolerable loneliness and consequent weight of responsibility that drove us to seek solace in the protective arms of authority – leaders who were fascist or democratic – for only that way could we avoid the fear generated by personal responsibility.

Where does this leave leadership? On the one hand, we can do without leaders if we want to organize social life through very small-scale and temporary networks, but anything larger or longer-lived seems to require some form of institutionalized leadership. The good news is that we now need to concentrate on mechanisms for holding such individual and collective leaders accountable and on creating a more responsible citizenship that is more willing to engage in acts of leadership. The bad news is that the assumption that somehow collaborative leadership is not as open to manipulation and corruption as individual leadership is highly suspect. We cannot achieve coordinated responses to collective wicked problems simply by turning our backs upon individual leadership – even collaborative leadership requires individuals to make the first move, to assume responsibility, and to mobilize the collective leadership. In effect, the members of the collective must authorize each other to lead because collectives are notoriously poor at decision-making. Leadership is not, then, the elephant in the room that many would rather not face up to; it is the room itself – which we cannot do without. This, in another world, is what Bauman calls, ‘the unbearable silence of responsibility’. And this is our collective and individual challenge.