Japanese Naval Aviation, 1909–1921

When the Imperial Japanese Navy was established in the 1870s, there existed a formidable gap between Japan and the Western maritime powers. These powers, led by Britain, had made epochal advances in naval technology, the tactical coordination of fleets, and the applications of sea power to achieve strategic objectives. Decades and in some cases centuries of naval evolution in the West confronted Japan with a daunting challenge. The Japanese navy was able to narrow this gap dramatically, but only through extraordinary effort intensified by a consciousness of Japanese inferiority and backwardness.

In the development of aviation, specifically naval aviation, the comparative situation was different. While manned flight in balloons had been undertaken in the West in the eighteenth century and powered lighter-than-air craft had been successfully tested in the middle of the nineteenth, heavier-than-air flight was not demonstrated as practical until the opening of the twentieth. When, in 1909, the Japanese navy first made a decision to develop a capability in this new medium, the Wright brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk and Samuel Langley’s abortive experiments on the Potomac River had occurred only six years before, and none of the pioneer endeavors of powered flight had yet demonstrated that aviation could contribute to the conduct of war on land or at sea. Yet soon thereafter, progress in aviation came with remarkable rapidity, and its principles were widely disseminated. The pace of this dissemination thus allowed Japan to participate in the general liftoff of aviation within a far shorter time than it had taken the nation to join the ranks of the great naval powers. Of course, Japan’s smaller resource base in science, technology, and materiel meant that the navy’s first decades of powered flight were greatly dependent on Western developments in aviation. In the long run, moreover, the rise of Japanese naval air power, as stunning as it proved to be by 1941, must necessarily be viewed against the material dominance of the West.

By 1911, naval aviation already offered two paths for development: the seaplane and the wheeled land-based aircraft. Because it was waterborne, the seaplane1 seemed the logical type of aircraft for naval operations. At San Diego that year, the American engineer Glenn Curtiss, who was pioneering the development of seaplanes, undertook the first waterborne flight, landing alongside a warship that then hoisted the aircraft aboard. Other seaplane records were set over the next ten years, and a mother ship, the seaplane tender or carrier, was developed by the leading naval powers as a new warship category. Yet the use of seaplanes with the fleet presented problems. They took too long to launch and recover, the mother ship having to stop and lower or retrieve her aircraft over the side.

The second approach to naval aviation was the employment of shore-based aircraft, but their range at that time was so short that they could not operate with the fleet. As early as 1910, the United States Navy made a historic effort to solve this problem by launching ship-borne aircraft. At Hampton Roads, Virginia, that year, an aircraft was flown off the temporary platform deck of an American cruiser, an event followed a few months later by the successful landing of an airplane on the temporary deck of a cruiser in San Francisco Bay. Yet these were flights by single aircraft from and to ships riding at anchor. No navy had yet attempted to launch or recover aircraft from a ship under way. Nor had any maritime power yet determined the role of such aircraft in the operations of its navy, though many naval professionals saw the function of both sea- and ship-borne aircraft as most likely one of reconnaissance, not combat. It would take World War I to change this limited perception of naval aviation.2

In that conflict, the impact of aviation on the war at sea was far less dramatic and wide-ranging than its effect on land war, but the airplane had, in isolated instances, demonstrated its potentially versatile role in naval operations. In 1913, even before the world war, a Greek seaplane carried out a reconnaissance sortie over a Turkish fleet in the Dardanelles. A British seaplane made a practice drop of a standard naval torpedo in 1914, and the next year British seaplanes heavily damaged a Turkish military transport in an aerial torpedo attack. In 1916, Austro-Hungarian seaplanes sank a French submarine at sea by bombing. Jutland itself was the first naval battle that involved naval aviation, though in a small role, when an aircraft from a British seaplane tender attached to the Grand Fleet spotted the advancing German battle cruiser squadron and reported the enemy’s movements accurately, though the British flagship did not receive the information because of a communications breakdown.3

Despite these “firsts,” however, the limitations mentioned earlier—the time-consuming process of launching and retrieving seaplanes at sea and the difficulty of launching more than a single aircraft from the temporary platforms installed on regular warships—kept naval aviation from playing a significant scouting or striking role at sea. To operate wheeled planes from ships under way called for a new kind of warship with wide and permanent decks for the launch and retrieval of numerous aircraft. In converting the battle cruiser Furious in 1917, so as to provide a permanent flight deck forward, the British navy produced the prototype of the modern aircraft carrier. In August of that year the first landing on a ship under way took place on its flight deck. The next year a landing flight deck was extended aft, though the warship’s funnel and superstructure still separated it from the takeoff deck forward.

FIRST FLIGHTS

The Japanese Navy Finds Its Wings, 1909–1914

In all such developments the Japanese navy had as yet little direct experience. At the end of the first decade of the new century, the issue of aviation in Japan was largely theoretical, tested in the press rather than in the air, since there were no aircraft of any sort in the country. But there were those who had at least begun to think boldly about the new subject of “aeronautics.” In the navy, a few officers, stationed abroad, including Comdr. Iida Hisatsune, resident at the Royal Navy’s Gunnery School in Portsmouth, and Lt. Comdr. Matsumura Kikuo, resident officer in France, had become interested in Western developments in powered flight and had begun to send reports back to Tokyo.4 But it was Lt. Comdr. Yamamoto Eisuke†—nephew of the powerful Meiji-era naval figure Adm. Yamamoto Gombei, but no relation to Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku of Pacific War fame—who can properly be called the conceptual father of Japanese naval aviation. While serving on the Navy General Staff, Commander Yamamoto became intensely interested in aviation through stories in the press about Western advances in the field. He subsequently drafted a number of pronouncements in which he urged the navy to address seriously the question of “flying machines” (tako-shiki kūchū hikōki, literally, “kite-type flying machine”). In his “Statement Concerning the Study of Aeronautics” (Kōkūjutsu kenkyū ni kan suru ikensho) of March 1909, Yamamoto predicted the advent of “aerial warships of awesome potential” and went on to argue that while naval warfare up to then had been two-dimensional, in the near future, with the addition of flying machines and submarines, it would be conducted within three dimensions.5 This view prefigured the arguments of air power advocates in the Japanese navy in the years to come. It obviously implied a challenge to the orthodox belief in the dominance of surface fleets, but it ascribed to aviation capabilities that it was decades from achieving—this at a time when “flying machines,” with their delicate assemblies of wood and wire and cloth, had the structure and the performance of a crane fly, and in a year when there was not as yet even one of these odd contraptions in Japanese military service.

In any event, Yamamoto’s various memoranda came to the attention of Navy Minister Saitō Makoto, who was sufficiently impressed with their dramatic claims to enter into negotiations with the army minister for a joint program to study the military application of flight to the conduct of war. The timing was fortuitous, for just about that time the army was beginning to move in that same direction. In 1909 the two services established a “Provisional Committee for the Study of the Military Application of Balloons” (Rinji Gun’yō Kikyū Kenkyūkai). Despite this oddly narrow focus for the study of military aviation, both the army and the navy continued to pursue heavier-than-air flight. The army sent several officers to Europe for flight instruction in the latest flying machines. Upon their return in 1910, they brought with them two aircraft for a public demonstration of the first heavier-than-air flights in Japan. The interest engendered in the army high command by the experiment led to the establishment of the first military airfield at Tokorozawa the next year.6

But the Japanese navy was determined to acquire its own wings. Given the friction that had existed between the two services since their creation, it was inevitable that the nature of the Provisional Committee—chaired by an army general, dependent entirely upon the army’s budget, and heedless of the navy’s interest in waterborne aircraft—would cause restlessness among its navy members. Most of those officers urged the navy to withdraw from the committee and to form its own aviation research organization. Thus, in 1910 the navy set out on its own course by establishing a “Committee for the Study of Naval Aeronautics” (Kaigun Kōkūjutsu Kenkyūkai), headed by Capt. Yamaji Kazuyoshi† and twenty-one other naval officers, most of whom went on to become the pioneers of Japanese naval aviation. This navy initiative caused a good deal of resentment in the army and marked the beginning of a bitter rivalry in aviation between the two services that lasted to the end of the Pacific War.7

The obvious first step in aviation for the Japanese navy was the development of a core of young naval officers who could fly and who then could teach others to fly. This, in turn, required that a few selected officers be sent abroad for flight training. While there, they could purchase and ship home the latest flying machines. Because France and the United States seemed to be making the greatest progress in aeronautics, it was to those two countries that the first Japanese officers, most of them members of the navy’s Aeronautics Committee, were dispatched.

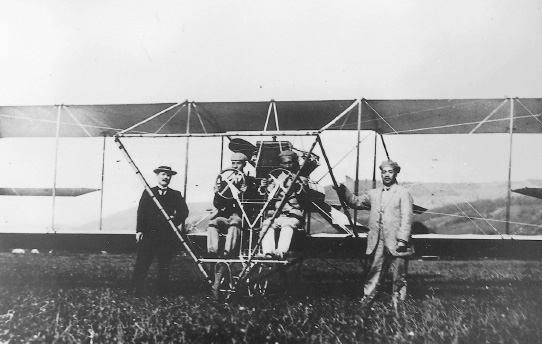

In 1911 to 1912, lieutenants Kaneko Yōzō,† Umekita Kanehiko, and Kohama Fumihiko were dispatched to an aviation school in Paris, and lieutenants Kōno Sankichi, Yamada Chūji,† and Nakajima Chikuhei† were sent to the Glenn Curtiss aviation schools in Hammondsport, New York, and in San Diego.8 At Hammondsport the Japanese trainees learned to fly the newly designed Curtiss seaplanes on nearby Keuka Lake and later took training on the Curtiss wheeled aircraft, popularly known at Hammondsport as “grass cutters.” Actually, only Kōno and Yamada were under orders for flight instruction on Curtiss aircraft. Nakajima was charged merely with studying the production and maintenance of such machines, but he took it upon himself to obtain flight training from Curtiss instructors.9 Judging from American accounts, the Japanese students exhibited more zeal and daring than natural skill, and as a result demolished several machines, much to the frustration of their American instructors.10

Meanwhile, Commander Yamamoto had been dispatched to Germany to learn all he could about European developments in military aviation. While there he corresponded frequently with Lieutenant Kaneko on the importance of aviation research for the Japanese navy. Seeking ways to demonstrate to the navy brass the possibilities for aviation, Yamamoto hit upon the idea of using the navy’s newly purchased foreign aircraft in the annual naval review held before the emperor. To that end, he fired off a recommendation to the navy minister for such a demonstration. Many in the top echelon were opposed, being skeptical of the whole idea of aircraft in naval warfare and fearful that an accident or a mechanical failure in either one of the aircraft would ruin the demonstration and embarrass the navy. But Navy Minister Saitō approved, and lieutenants Kōno and Kaneko were ordered to hurry back from the United States with their aircraft—a Curtiss seaplane and a Maurice Farman seaplane, respectively—to take part in the review. In the fall of 1912 these aviators made the first flights in Japanese naval air history at Oppama, just north of Yokosuka, which was to become Japan’s first naval air base. The Farman seaplane was assembled at Oppama, and on 6 October 1912 Kaneko made a test flight of the aircraft for fifteen minutes, reaching an altitude of 100 feet (30 meters). On 2 November, Kōno flew the Curtiss seaplane for about ten minutes, also reaching an altitude of 100 feet. Then, on 12 November, the two lieutenants put on a demonstration of their aircraft at the imperial naval review at Yokohama. Kaneko flew the Farman from Oppama, alighting on and taking off from the water near the ship carrying the emperor Taishō, and Kōno piloted the Curtiss in a circuit over the naval ships in the review.11

In such fragile and clumsy contraptions the navy had now tested its wings, but whether they would become anything more than an entertaining curiosity remained an open question for much of the navy brass. Still, there was now a sufficient, if small, core of aviation enthusiasts among the junior officers and a few interested flag officers to push along the development of aviation in the navy.12 Keeping abreast of foreign aviation progress was obviously essential to that purpose, and in December 1912 Captain Yamaji and Lieutenant Kōno were sent to France, Germany, and Britain on a fact-finding mission. While in Europe they studied various kinds of airships, picked up rumors about airborne radio communications, watched a demonstration of aerial bombardment in France, and observed that in all three navies the preponderance of aircraft consisted of seaplanes.13

Among their observations was their assessment that ships able to launch and retrieve wheeled aircraft would be an inevitable development in future naval warfare, though they conceded that it was unclear how such a warship type and its aircraft would influence conventional surface warfare. In any event, they concluded, navy pilots should practice short takeoffs and landings on fields ashore until suitable ship platforms could be developed. In the meantime, however, they recommended a continued emphasis on seaplanes and the development of more coastal sites from which they could be launched.14

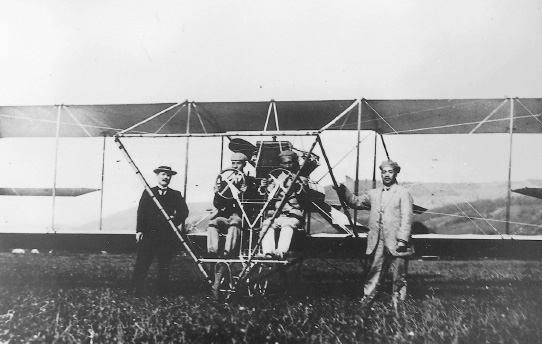

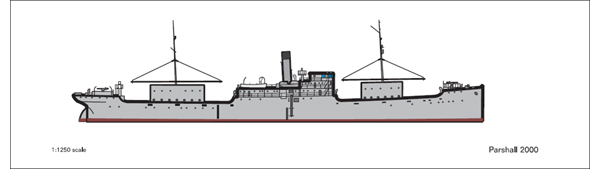

In late 1913 the navy’s decision to push ahead with seaplanes led to the development of its first specialized vessel for handling waterborne aircraft. This was the Wakamiya Maru, a converted freighter, which had simple derricks and canvas hangars fore and aft and was capable of carrying two assembled and two disassembled seaplanes.15 In the annual naval maneuvers off Sasebo that year, it was as a seaplane carrier that she loaded several Farmans at Yokosuka to test the usefulness of aircraft in fleet reconnaissance. The seaplanes aboard the Wakamiya Maru, organized into a “seaplane unit” (suijōki butai), served the “Blue Fleet” (the “attacking force”) while three seaplanes were kept at Oppama to serve the “Red Fleet” in defense.16

As it was in the U.S. and British navies, lack of a rapid means of communication—between aircraft, and between aircraft and ships—was an early impediment to integrating aircraft with the Japanese fleet. Some tests using radio telegraph were carried out, but this means proved unsatisfactory because of the primitive nature of the equipment. In these early years, hand flags were used for communication from aircraft. One of the early naval aviation pioneers, Wada Hideho,† later recalled that when communicating with other aircraft, crewmen actually stood up in their seats and gave arm signals with flags tied from elbow to wrist. For communication from aircraft to ships, Japanese naval aviators dropped weighted rubber balls with messages inserted into them and with colored streamers attached to make them easier to see when dropped.17

Fig. 1-1. Seaplane carrier Wakamiya

THE FIRST TEST OF COMBAT

Japanese Naval Aircraft in the Tsingtao Campaign, September–October 1914

While histories of Japanese naval aviation mention no particular feats by these flimsy aircraft during the maneuvers of 1913, the test of the navy’s fledgling air unit in actual combat was not long in coming. In September of the next year, within two weeks of Japan’s declaration of war on Germany and the preparations for the reduction of German territories in Asia and the Pacific, the Wakamiya Maru and her aircraft were assigned to the navy’s Second Fleet. That force departed Yokosuka on 23 August to take part in the blockade and reduction of the German naval base at Tsingtao, China. Aboard were Lt. Comdr. Kaneko Yōzō (the senior air officer afloat), lieutenants Kōno Sankichi (the group’s executive officer), Yamada Chūji, Wada Hideho, Magoshi Kishichi, and Fujise Masaru, and several other junior officers—nearly all the navy’s “experienced” aircrew.18

Embarked on the Wakamiya Maru were four Maurice Farman seaplanes, aircraft that could attain a speed of 50 knots and had a ceiling of 500 meters (1,500 feet) when fully loaded. While their mission was expected to be principally reconnaissance, the navy also expected them to bomb targets of opportunity. But the means by which they were to do so were ridiculously slight by the standards of tactical bombardment that would evolve only a few years later. The planes had crude bombsights and carried six to ten bombs that had been converted from ordinary shells and were released through metal tubes on each side of the cockpit. The pilots were able to communicate with each other only by flag signals.19

On 1 September the Wakamiya Maru arrived off Kiao-chou Bay where the Second Fleet had already supported a Japanese army landing. Bad weather and a number of mishaps kept the ship’s aircraft from taking off for some days. Then, on 5 September, in the first successful Japanese air operation, Lieutenant Wada, flying a three-seat Farman seaplane and accompanied by Lieutenant Fujise, piloting a two-seater Farman, rose clumsily into the air and headed toward the Bismarck battery, the main German fortifications at Tsingtao. When directly over the battery, Wada dropped several bombs that landed harmlessly in the mud—a disappointing beginning to the history of air bombardment. But the main value of the navy’s early aviation was demonstrated almost immediately. Soaring over Kiao-chou Bay, the Japanese pilots were able to see which German ships were still at anchor and which had successfully reached the open sea. Their confirmation that the cruiser Emden, the most powerful remaining unit of Germany’s Asiatic Squadron, was no longer in harbor was intelligence of major importance to the Allied naval command.20

Photo. 1-2. Farman seaplane being hoisted aboard the seaplane carrier Wakamiya Maru, 1915

On 30 September the Wakamiya Maru had the misfortune to be holed by a German mine, and after being patched up she was eventually sent back to Japan. Her aircraft were transferred to a strip of Japanese-held beach from which they continued to conduct reconnaissance and bombing missions during the remaining month of the one-sided campaign against Tsingtao. The best opportunity for aircraft-to-aircraft combat came about on 13 October, when Lieutenant Wada, in cooperation with three army aircraft, set out to attack the lone German navy airplane that had been used by the defenders for reconnaissance. The encounter was inconclusive; after much dancing about in the sky over the bay, the German aircraft, too nimble for its pursuers, escaped into a cloud.21 By the end of the siege, the navy had conducted nearly fifty sorties against Tsingtao, had undertaken various search missions at sea, and had dropped nearly two hundred bombs, though damage to German defenses may have been slight. With the surrender of the fortress, the navy’s air unit was withdrawn.22

In the greater scheme of World War I, the navy’s air operations over Tsingtao were a footnote in a campaign that was itself a footnote in the history of the war. Certainly the meager operational results had given the navy brass no reason to suppose that these fragile bundles of struts and wires would supplant the surface battle line as the locus of naval power. Yet if nothing else, the Tsingtao operations confirmed for the navy’s tacticians the fact that aircraft, far better than any surface vessel, could act as the eyes of the fleet. That in itself was a significant step forward for Japanese naval aviation. Viewing the air operations at Tsingtao as a whole, Charles Burdick, the acknowledged authority on the siege, has asserted that “the sophistication of Japanese aircraft employment—i.e., coordination with land forces, bombing equipment, and general mobility—was well ahead of any other country.”23

WATCHING FROM THE SIDELINES

Development of Japanese Naval Aviation, 1916–1920

Japan’s swift operations to seize the German territories in Asia and the Pacific were completed by November 1914, following which the nation became largely a passive belligerent. Except for the dispatch of light naval forces to the Mediterranean in 1917, Japan was content to watch from the sidelines as the endless and futile offensives dragged on in Europe. But such a posture cost the Japanese a firsthand understanding of the conduct of modern naval war. This was particularly true in the field of naval aviation, where, at the outset of World War I, Japan had gained experience ahead of the Western naval powers. By 1918, however, aviation had become a standard element in Western naval power, taking on new and important roles in reconnaissance and antisubmarine patrol work; naval aircraft had grown significantly in capabilities and performance, and naval aviation had been given its longest reach yet with the development of the first aircraft carriers.24

All this had yet to be mastered by the Japanese navy, which did its best to monitor the tactical and technological developments in the naval war through observers dispatched to the European theater. The evolution of naval aviation was a significant, though not major, element in the navy’s interest in the conduct of the war in Europe. The navy not only made use of the reports of Japanese naval attachés stationed in Allied capitals but also dispatched observers with specific missions to collect information on Western progress in military and naval aviation. In this way, Lieutenant Kaneko was sent to tour Europe and the United States in 1916–17 to gather information on the construction of the first proto–aircraft carriers. Lt. Kaiya Masaru went to France in September 1916 to observe French army air groups and pilot training. Lt. Kuwabara Torao† spent the latter half of 1917 getting a detailed picture of British naval aviation. Kuwabara was able to observe naval balloon units and flying-boat operations at Felixstowe and to visit the construction site of the Argus (the Royal Navy’s first flush-deck carrier). He then went aboard the proto-carrier Campania to experience two weeks of aerial patrols during British fleet operations.25

Of particular importance among the reports of these naval observers was the memorandum drafted by Capt. Torisu Tamaki,† who was an observer with the British navy, 1916–17. Included in his “Summary of Operations of the British Grand Fleet” was a section on aviation that detailed the British use of airships to patrol ahead of the fleet, warn of enemy attacks, reconnoiter enemy coastlines, and undertake photoreconnaissance. The report provided detailed information on the conversion of the Furious with a foredeck flight platform and alerted the Japanese navy to the construction of the Hermes, Britain’s first built-for-the-purpose through-deck carrier (i.e., a carrier without any obstruction—funnels or bridge—across the flight deck).26

But the most detailed and influential policy statement on the development of aviation in the Japanese navy was a report—“On the Stagnation of Naval Aviation and Other Matters” (Kaigun kōkū no fushin sono ta ni tsuite)—issued by the Navy Ministry in December 1919. Drafted by Capt. Ōzeki Takamaro, the report pointed out that Japan’s isolation from the recent war’s main combat theater meant that Japan had fallen considerably behind the other Allied powers in naval aviation and that in order to catch up with these powers the navy needed to take a number of steps. First, the navy must decide on what sort of aircraft it required, and then it should begin to produce these in Japan, under licensing arrangements if necessary. Second, it needed to invite foreign instructors, most probably British, to provide instruction in flight operations from warships configured to carry wheeled aircraft and to provide counsel on the manufacture of aircraft in Japan. Third, naval air strength had to be augmented by increasing the number of land-based air units, by converting a conventional warship to an aircraft carrier, and by building two fleet carriers. All this should be accomplished within eight years. Finally, Ōzeki urged, the navy ought to investigate the naval air organizations of other countries and adopt the best features of each.27

THE VISIONARIES

The Navy’s Early Air Power Extremists

These official reports and recommendations by aviation advocates were effective in promoting practical measures to develop aviation as part of the regular naval establishment, though Navy Minister Katō Tomosaburō, in Diet interpolations at the end of 1919, made it clear that the navy was still focused on a “battleship-first” policy.28 Outside the range of the moderate approaches to aviation, however, there existed an array of radical visions and prophecies by a few naval officers who envisioned aviation not merely as a supporting component of conventional surface warfare but as the dominant element of naval war. As we have seen, Commander Yamamoto had been one of the first to give voice to such an argument. Others among the small and youthful band of aviation pioneers in the navy spelled out more precisely how aircraft would be potent weapons in the naval tactics of the future. In 1912, while training in France, Kaneko Yōzō had written to Yamamoto:

Operating in good weather on either a moonlit or a moonless night, aircraft could, in cooperation with torpedo boats, attack enemy warships in harbor. Moreover, there would be nothing to prevent aircraft from entering a harbor fortified against surface attack and strike enemy warships from above. And, in the case of blockading operations, when enemy warships must inevitably try to escape, it is hard to imagine a more useful weapon.29

Others, with the passion of the newly converted, drew more sweeping pictures of the future dominance of air power. Before World War I, one of the more daredevil figures to do so was Engineer Lt. Isobe Tetsukichi, who first demonstrated his enthusiasm for aviation by building his own seaplane out of bamboo and flying it for 60 meters (200 feet) at a height of 3 meters (10 feet) before the machine overturned—this a year before the navy imported its first seaplane. Isobe went off to Germany in 1913 for flight training and returned in time to join the Tsingtao campaign. Flying an army aircraft in a test flight, he crashed. He was repatriated to Japan because of his injuries but soon became restless and eager for more aerial combat. He somehow managed to join the French army air service and participated in the Verdun campaign but again crashed, this time suffering serious wounds, and was once more sent back to Japan. His flying career at an end, Isobe put his convictions to paper. In 1918 he published a short work, “War in the Air” (Kūchū no tatakai), in which he predicted that those nations able to dominate the air would soon dominate the land and sea as well. Taking note of the ability of Germany to bomb the British Isles during the recent war, Isobe argued that enemy aircraft based at Vladivostok or Shanghai could just as easily strike at Japan. Foreshadowing the destruction wrought by American B-29s at the end of the Pacific War, Isobe predicted that Japanese cities would burn like matchwood under such an aerial assault.30

But the air power statement that most directly confronted naval orthodoxy had been drafted three years earlier. In January 1915 the future aircraft industry magnate Nakajima Chikuhei, then a young engineer lieutenant, had sent to the chairman of the navy’s Aeronautics Committee a memorandum outlining his views on weapons procurement for the navy. The thrust of the memorandum was that even though the airplane was in its infancy, it was destined to be the decisive weapon of the future, and the dreadnought battleship was now fatally threatened by the aerially launched torpedo and mine. For that reason and because aircraft technology was advancing so rapidly, the considerable sums spent on the construction of capital ships could be better spent on aircraft design and production. For example, Nakajima argued, the immense costs of the construction of the battle cruiser Kongō could have paid for some three thousand aircraft, each one of which could carry a torpedo load more powerful than one of the Kongō’s broadsides (which, of course, was a wildly inaccurate statement). On the eve of his resignation from the navy to begin his career as a manufacturer, Nakajima had incorporated the main arguments of his memorandum into a circular letter that he had sent around to all his friends and acquaintances.31

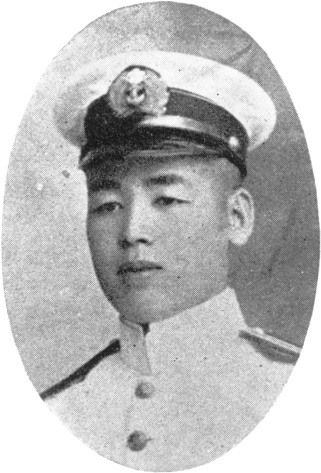

Photo. 1-3. Nakajima Chikuhei (1884–1949) as a young naval officer

This was a very bold, if exaggerated, air power manifesto, the first made in any nation, coming as it did substantially before that of Giulio Douhet in Italy or “Billy” Mitchell in the United States. But it was the argument of a visionary, not a realist. The realities of aircraft technology for the next several decades made it hardly likely that such frail machines could accomplish all that Nakajima and the more extreme air power advocates expected of them. Moreover, given the naval wisdom of the day, it is not surprising that Nakajima’s statement had little immediate impact on naval circles. Asked in the Diet, in 1916, about the impact of air power in relation to naval warfare as it was then understood, Navy Minister Katō Tomosaburō declared with confidence that there was as yet no aerial bomb that could put a warship out of commission. That didn’t mean that the navy shouldn’t make sure that in the future its warships were safe from aerial attack (by either bombs or torpedoes), but for the present, most of these dangers were largely theoretical. For that reason, Katō assured his listeners, the Japanese navy did not regard the advent of aircraft as upsetting the traditional dominance of the battle fleet.32 Considering the limited bomb loads, the ranges, the speeds, and the bomb-sighting systems of aircraft of the time, this was not an unreasonable assumption. But as aircraft technology evolved and the reach and destructive potential of naval aviation emerged, the arguments of the air power advocates increasingly came to challenge the battleship orthodoxy of the navy.

PRACTICAL ADVANCES

Air Training, Air Groups, and the Search for Administrative Unity

In the decade prior to 1920, the course of naval aviation was in the hands of those more interested in making solid organizational advances within the navy than in making sweeping theoretical claims for the future of air power. Over a five-year period, 1916–21, the reports and recommendations of the naval commentators already mentioned—particularly those of Captain Ōzeki—stimulated the navy to undertake a number of parallel efforts to further the progress of naval aviation: the beginning of a regular and systematic program of naval air training; the creation of the navy’s first permanent shore-based air groups; an attempt to establish a single administrative organization for naval aviation; a brief exploration of the possibilities of lighter-than-air aviation; the construction of Japan’s first aircraft carrier, and the creation of a training program for flight operations to be conducted from it; and the invitation of a British aviation mission to facilitate the development of naval air training and to promote the manufacture of naval aircraft in Japan.

The first and most critical steps in the enhancement of aviation’s role in the navy was the expansion of the cadre of aircrews and the creation of a systematic program of flight training. In 1912, after the return from abroad of the pioneer aviators mentioned earlier, flight training had begun at Oppama for selected personnel. Following the practice in Western navies, this training was at first limited to officers, though noncommissioned officers were permitted to occupy the cockpit beginning in 1916. The training itself was largely confined to simple operational procedures, but in these early years of Japanese naval aviation, such training was incredibly haphazard and limited. Because of a shortage of aircraft, the average in-air training session lasted only ten to twenty minutes per pilot, and in an entire year of training few students received more than forty-five minutes in the air. Once a trainee went up solo, he was judged sufficiently qualified. Naturally, with such limited time in the cockpit, there were fairly frequent crashes and forced landings by the navy’s pioneer aviators. Considering the rough handling the navy’s few aircraft received, it is a wonder that there were not more such accidents; remarkably, there were none at all in the Tsingtao campaign.33 Over time, flight training in the navy improved, but this came only with the establishment of permanent and specialized facilities, which in turn depended upon the creation of permanent air units.

The navy’s seaplane unit, which had been assembled for participation in the Tsingtao campaign, had never been thought of as a permanent unit and was organized only on a temporary, annual basis for participation in fleet exercises. But with the dissolution of the original committee that had initiated naval aviation, funds were released in 1916 for the establishment of three permanent air groups (kōkūtai), which were to be established in peacetime as needed at designated naval ports or naval bases. These groups took their designation from the names of those ports and bases, and fell under the authority of each local port or base commander. (A more detailed explanation of the kōkūtai system and an enumeration of the navy’s land-based air groups, 1916–21, is provided in app. 5.) The first air group was established at Yokosuka in April 1916, and because the air base on which it was stationed was charged with responsibilities for naval air training and naval air development, for most of its early years the group had the character of a training unit. The first really operational naval air group was not organized until 1920 at Sasebo.34

Yokosuka and Sasebo were initially bases for seaplanes only, but a number of leading aviation pioneers, Lieutenant Commander Kaneko among them, had long believed that the navy needed land bases for wheeled aircraft as well. At the time, the army was dickering for the use of Kasumigaura, a lakeside base in Ibaraki Prefecture, north of Tokyo, ideal for both wheeled and pontoon aircraft. The navy bought the land, forestalling the army, and in 1922 a third air group was established at Kasumigaura. The Kasumigaura Air Base became the center for pilot training. At the same time, a fourth air group was established at Ōmura, Nagasaki Prefecture, which later in the decade became a fighter base.35

The creation of permanent land-based air groups and the increasing importance of aircraft in the navy’s exercises and maneuvers provoked calls by aviation advocates for a single administrative organization for aviation. Until 1916, control of aviation had been held by the Navy Technical Department, but that year it was transferred to the Navy Ministry’s Naval Affairs Bureau. Proposals for enhancing the importance and coordination of aviation ranged from the establishment of an aviation section within the Naval Affairs Bureau to the creation of a separate Naval Aviation Department. But the idea of a semiautonomous air agency was quickly set aside. The mainstream view was that because aviation was no different from gunnery or torpedo warfare, a separate administrative organization was not necessary. More important, perhaps, the top brass did not believe that aviation would be a critical element in naval warfare. On the other hand, uncertain as to what role aviation would play in the future, the navy brass did not wish to relinquish control over its direction. Thus, the greatest organizational identity that the navy would concede to aviation was a small Aviation Department created in 1919 within the Naval Affairs Bureau, later redesignated the Third Section of the bureau. When this office was abolished in 1923, there was no remaining naval air advocate with sufficient stature to resist the demands for the breakup of naval aviation. Hence, its various activities were divided among several bureaus and departments within the Navy Ministry.36 It would be four more years before an officer of energy, foresight, and influence could give it a powerful and unified presence within the navy.

LIGHTER-THAN-AIR AVIATION IN THE NAVY

In the meantime, the Japanese navy continued its effort to keep abreast of developments in all aspects of aviation. Toward the end of World War I, both the British and American navies devoted considerable effort to the development of semirigid airships, in large part because of the effectiveness of German Zeppelins during the conflict. The Royal Navy had begun using airships in reconnaissance as early as 1917 and subsequently undertook research and training relating to such craft. The United States Navy, thanks to America’s great supply of helium, which reduced the danger of explosion and made its airships somewhat safer, made even greater strides in this technology. In view of these advances, the Japanese navy began to investigate the utility of airships in its own tactical and strategic schemes. In 1918 it established a lighter-than-air unit at its Yokosuka base (later moved to Kasumigaura) and began acquiring airship technology from abroad. The first lighter-than-air craft acquired by the navy were simply large balloons (kikyū) that were tethered to warships and used for shell spotting and torpedo tracking. In 1921 the navy acquired several semirigid and self-propelled airships (hikōsen) from Britain, France, and Italy. After successful tests integrating these craft with fleet operations, the navy began to construct its own airships of this type. After 1921, rigid airships were attached to the Combined Fleet and regularly took part in the navy’s annual maneuvers.37

During the 1920s a number of officers on the Navy General Staff saw the rigid self-propelled airship as a significant component of the navy’s defensive strategy in the western Pacific. Because of its greater endurance, such a craft offered the possibility of locating enemy fleet units far beyond the range of winged aircraft of the time. Armed with bombs to attack enemy ships and machine guns to defend itself, the airship could, its advocates argued, provide the navy with a long-range strike capability. Yet major doubts persisted. To begin with, all three major navies suffered a number of accidents involving airships, the most spectacular being the crash of the American Shenandoah in 1925, which raised questions as to the reliability of airship technology. The Navy General Staff, moreover, pointed to the liabilities of the airship. It was vulnerable to damage or worse in rough weather, as the number of crashes in the British and American navies demonstrated. It presented a large, soft target for enemy fighter aircraft. It was expensive to build, and its supposed military utility was a matter of speculation, not proof.

Ultimately, the emerging potential of winged aircraft turned the Japanese navy away from further development of the airship. Given the expense of rigid airship construction and the continuing doubts as to its utility and viability in combat, the winged airplane appeared to be a more promising agent for the navy’s bid to enter the new dimension of the sky. Undoubtedly too the airship—large, slow, and ungainly—could hardly compete with the glamour of winged aircraft as an object of enthusiasm for aviation advocates in the navy. For all these reasons, the navy decided in 1931 to abolish its airship units and, over the next few years, to phase out the airships attached to the fleet.38

FURTHER ADVANCES

Naval Aviation Extends Its Reach

In any event, the future of Japanese naval aviation rested on wings and engines, not on airships. In such aircraft, navy pilots, with enhanced skills, flying better and bigger aircraft, began to make flights of increased time, distance, and height. In February 1914, Lt. Magoshi Kishichi, piloting a Farman seaplane, reached a height of 3,500 meters (11,500 feet), and a month later, flying the same sort of aircraft, he flew nonstop for six hours. In the spring of 1918, three Farman seaplanes flew from Yokosuka to Sakai nonstop. In April 1920, three Yoko-type seaplanes flew from Yokosuka to Kure to Chinkai (Chinhae), Korea, to Sasebo and back to Yokosuka. The last leg took eleven hours and thirty minutes—a historic flight, since up to that time no aircraft of any country had flown for more than ten hours without landing.39

Aircraft also began to take an important role in the annual naval exercises. In the grand maneuvers of 1919 a seaplane from the Wakamiya, attached to the “Blue Fleet,” was able to discover the main body of the “Red Fleet” far over the horizon and to report this intelligence by dropping a marker on the deck of the “Blue Fleet” flagship, an event regarded as a great success at the time. This achievement was repeated by both fleets in the grand maneuvers south of Honshū two years later. About the same time, navy aircraft also proved useful in the protection of Japanese civilians in Karafuto and the Russian Maritime Provinces during Japan’s Siberian intervention by providing reconnaissance and aerial demonstrations. The campaign was also an opportunity for testing cold-weather flight operations.40

During World War I, Japanese naval observers quickly noticed the different emphases in aviation between the U.S. and British navies. The United States Navy relied mostly on seaplanes and shore-based wheeled aircraft for its air capabilities, while the British had come, by the end of the war, to emphasize carriers as the basic naval aviation force. As it had in other, earlier naval matters, the Japanese navy decided to follow the British rather than the Americans, for the time being. Recommendations from Japanese observers aboard the Royal Navy’s first carrier, the Furious, were undoubtedly instrumental in moving the Japanese navy toward plans for the construction of its first carrier, the Hōshō. This vessel was laid down in December 1919 in the Asano yard at Yokohama. After the British Hermes, she was the first warship to be designed from the keel up as a carrier and the first to be completed as such. Yet the construction of this 7,470-ton warship was an act of faith. There was as yet no doctrine for her employment, nor were there any aircraft suitable for flight operations from her deck. Indeed, the construction of the Hōshō, while undertaken with extensive British counsel, was largely a matter of experiment, reflecting the uncertainties of carrier design at the dawn of the air age.41 Yet the decision to build a carrier was a significant step in extending the reach of the Japanese navy.

THE SEMPILL AIR MISSION TO JAPAN

While the Japanese navy had endeavored to monitor the progress of aviation in all of the three major Allied naval powers during World War I, by the end of the war aviation specialists in the navy had concluded that it was Britain that had made the greatest advances in naval aviation. For that reason, the Japanese government decided to seek British aid in acquiring a professional edge to this newest arm of the Japanese navy.

During the 1920s, Japan was of two minds about the strategic implications of aviation. On the one hand, like a number of European powers, Japan came to exaggerate the capabilities of air weapons as they existed at the time. Along with their opposite numbers in Britain, the Japanese military and political leadership, drawing upon the “lessons” of the early advances in aerial bombardment during the recent world war, came to fear the enormously destructive consequences of such a campaign launched against the home islands. The advent of the aircraft carrier and its seeming ability to bring aerial bombardment to Japanese shores appeared to confirm these pessimistic speculations. It is not surprising, therefore, that at international conferences on disarmament and on the conduct of war, Japan strongly condemned aerial bombing and supported limitations on carrier construction. Japanese representatives at the Washington Naval Conference and at the Hague Conference of Jurists urged the outright condemnation of, or at least restrictions on, aerial bombardment in general, and on the bombing of cities in particular. Before and after the Washington Treaty, therefore, the Japanese sought restrictions on carrier tonnage, though the navy wished to keep its options open concerning the construction of this type of warship.42

Yet as we have seen, the Japanese navy had not been slow to adopt the new aviation technology and training; its first pilots had taken to the air only a few years after pioneer military aviators in the West. Before the end of World War I, Japan had begun to develop its own aircraft industry; at the outset of the war, it had even undertaken minor aerial operations against enemy surface units; and it had launched one of the world’s first carriers following the war. But in training and technology (one cannot really speak of a naval air doctrine in the immediate postwar years), Japanese naval aviation was still largely dependent upon the West. Many of Japan’s pilots had trained abroad. Most of its aircraft were of foreign manufacture, and those few that were domestically produced were largely of foreign design. It is unlikely, moreover, that Japan’s first carrier, the Hōshō, could have been completed so quickly without British technical assistance.

In these early years of Japanese naval aviation, the nucleus of specialists—pilots, gunners, navigators, and ground crews in the navy, and aircraft designers and manufacturers outside it—was neither sufficiently large nor sufficiently advanced technologically to keep up with the rapid pace of aviation developments elsewhere in the world, let alone capable of enabling the Japanese navy to pursue its own innovations. During the world war, the gap in aviation technology and aircrew proficiency between Japan and the West had widened considerably. Not only had the European belligerents gained valuable experience in aerial combat, but they had been able to mass-produce planes with dramatically better performance than prewar aircraft. The postwar decade in Japanese aviation was therefore marked by two related and intensive efforts: the infusion of considerable amounts of Western technological and training assistance and, at the same time, an effort by Japan to establish its own fledgling aircraft industry.

The Japanese navy’s initiatives in aviation arose from both international and domestic competition. On the one hand, the navy had to be concerned with recent advances in naval air technology in the American and British navies that threatened to leave Japan in a distant third place as a modern naval power. On the other, it had reason to be chagrined at the rapid advances in Japanese army aviation made possible by the arrival of a French air mission under Col. Jean Faure, invited to Japan in 1919 at the behest of the army.43

It was for these reasons that the Japanese naval leadership, following the recommendations of the Ōzeki report, decided in 1920 to seek the assistance of the British navy in improving the proficiency of its naval air arm. That summer, through the good offices of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, the navy requested that a British naval aviation mission be sent to Japan.44 As the Japanese navy’s old mentor and as the world leader in naval aviation at the time, the Royal Navy was, of course, a logical choice. Yet more prescient, perhaps, than either the British Foreign Office or the British Air Ministry, the British Admiralty had serious reservations about granting Japan unrestricted access to British technology in what might become a formidable new weapons system. The hopes of the British aircraft industry for aircraft sales to Japan, however, combined with the British navy’s dismissive attitude toward Japanese flying skills, led to a compromise. After a certain amount of backing and filling, the British government proposed to send an unofficial civil aviation mission to Japan, an offer accepted in November 1920 by the Japanese government. The mission of thirty men arrived at Kasumigaura in 1921. Its leader was Sir William Francis-Forbes (later Baron) Sempill, a former officer in the Royal Air Force, experienced in the design and testing of Royal Navy aircraft during World War I. His hand-picked team members were largely men with experience in naval aviation and included pilots and engineers from several British aircraft firms.

Photo. 1-4. The Baron Sempill and the Baroness Sempill in Japanese dress

The Sempill Mission, which lasted a year, provided the Japanese navy with a quantum jump in aviation training and technology.45 Initially it emphasized flight training. The mission staff provided some five thousand hours of in-flight training to Japanese student fliers. But instruction was soon expanded to include air combat, particularly dogfighting as developed by the British during World War I, high-level bombing, aerial torpedo attacks, reconnaissance, aerial photography, and the handling and maintenance of various types of aircraft.46

As important as the training it brought to the development of Japanese naval aviation was the considerable access to the latest aviation technology that the 33 mission provided. Not only did the trainees become familiar with the latest aerial weapons and equipment—torpedoes, bombs, machine guns, cameras, and communications equipment—but the mission also brought to Kasumigaura well over a hundred aircraft, comprising twenty different models, five of which were then in use in the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm. Several of these planes eventually provided the inspiration for the design of a number of Japanese naval aircraft during the 1920s.

Contemporaneous with the mission, technical and training assistance from British private firms was also made available to the Japanese navy. In February 1923, for example, a British pilot/technician, William Jordan, a former captain in the Royal Navy Air Service and now in the employ of the Mitsubishi Aircraft Company as an engineer and test pilot, was chosen to make the first takeoff and landing on Japan’s new carrier, the Hōshō. Once he had demonstrated the techniques for proper flight operations off a carrier, he was followed by the navy’s first carrier pilots, including lieutenants Kira Shun’ichi,† Kamei Yoshio,† and Baba Atsumaro.47

Thus, by the time the last members of the Sempill Mission had returned to Britain, the Japanese navy had substantially improved its naval air training program, had begun to understand the rudiments of carrier flight-deck operations, had become familiar with such naval air tactics as existed at the time, and had acquired a reasonable grasp of the latest aviation technology. The navy’s task was now to use these advances to launch itself skyward on its own wings.