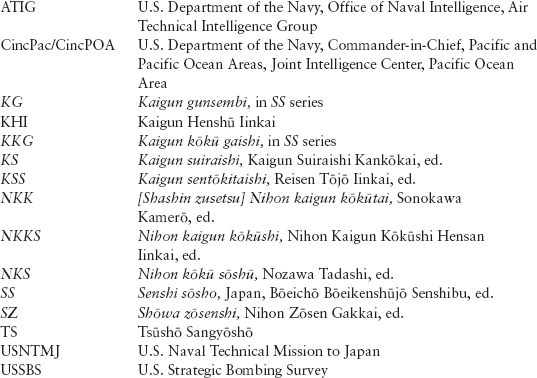

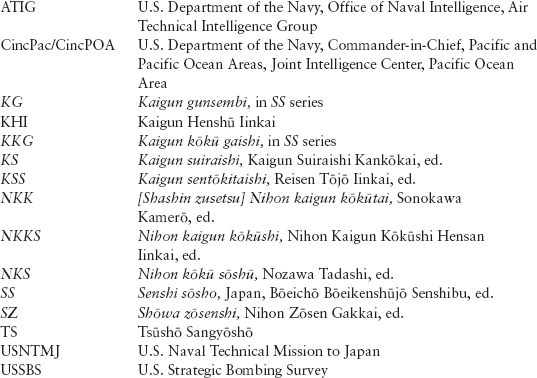

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN NOTES

ATIG |

U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Intelligence, Air Technical Intelligence Group |

CincPac/CincPOA |

U.S. Department of the Navy, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific and Pacific Ocean Areas, Joint Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area |

KG |

Kaigun gunsembi, in SS series |

KHI |

Kaigun Henshū Iinkai |

KKG |

Kaigun kōkū gaishi, in SS series |

KS |

Kaigun suiraishi, Kaigun Suiraishi Kankōkai, ed. |

KSS |

Kaigun sentōkitaishi, Reisen Tōjō Iinkai, ed. |

NKK |

[Shashin zusetsu] Nihon kaigun kōkūtai, Sonokawa Kamerō, ed. |

NKKS |

Nihon kaigun kōkūshi, Nihon Kaigun Kōkūshi Hensan Iinkai, ed. |

NKS |

Nihon kōkū sōshū, Nozawa Tadashi, ed. |

SS |

Senshi sōsho, Japan, Bōeichō Bōeikenshūjō Senshibu, ed. |

SZ |

Shōwa zōsenshi, Nihon Zōsen Gakkai, ed. |

TS |

Tsūshō Sangyōshō |

USNTMJ |

U.S. Naval Technical Mission to Japan |

USSBS |

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey |

CHAPTER 1. THE NAVY TESTS ITS WINGS

1. The original terms for this type of aircraft were “hydroplane” or “hydroaeroplane” and then “floatplane.” The word “seaplane” was supposedly coined by Winston Churchill during his tour at the British Admiralty. Layman, Before the Aircraft Carrier, 34.

2. Wragg, Wings over the Sea, 9–25; Melhorn, Two-Block Fox, 6–10.

3. Wragg, Wings over the Sea, 18, 24, 29–34; Popham, Into Wind, 52–55.

4. Kuwabara, Kaigun kōkū kaisōroku, sōsō-hen, 42–44.

5. Yamamoto Eisuke, Nana korobi, 219–20; NKKS, 1:53; KHI, Kaigun, 13:24–25.

6. Yamamoto Eisuke, Nana korobi, 229; Sekigawa, Pictorial History, 10.

7. NKKS, 1:58–59.

8. KHI, Kaigun, 13:25–26; NKKS, 1:61–63, 2:772. Curtiss, a pioneer industrialist in American aviation, had opened a flight school at Hammondsport, N.Y., in 1910. At the end of that year he also set up operations at North Island in San Diego, where flight training could continue during the winter months. Though Curtiss began with the training of U.S. Army and Navy pilots, he soon opened his doors to foreign students, and by the time the Japanese officers arrived in the spring of 1912 the school had developed a truly international student body. Kirk House (curator, Curtiss Museum, Hammondsport), letter to author, August 1996.

9. Mōro, Ijin Nakajima Chikuhei hiroku, 162–63.

10. Studer, Sky Storming Yankee, 300–302; Kirk House, letter to author, July 1996. The two instructors at the school were Francis Wildman and Lansing J. Callan, who had learned to fly at the Curtiss schools two years before. Callan eventually entered the United States Navy and went on to attain flag rank. His large collection of photos of the early aviation history at Hammondsport is housed at the Curtiss Museum there, along with a newspaper clipping dating from the early months of the Pacific War in which Callan, reflecting on the early flight training he gave to Nakajima Chikuhei, was quoted as saying, “I should have dunked him!”

11. NKKS, 1:59, 63; KHI, Kaigun, 13:27; Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 8.

12. These included Vice Adm. Shimamura Hayao, the father of modern Japanese naval tactics, who, as commander of Japanese naval units participating in the international naval review held in Britain in honor of the coronation of King George V, crossed over to Le Havre to inspect the flying school being run by Maurice Farman. While there he was invited by Farman to go up in one of his aircraft. His flight was the first such venture by a flag officer of any navy. NKKS, 1:61.

13. Ibid., 63–65.

14. Ibid.

15. Ikeda, Nihon no kaigun, 2:37; Jentschura et al., Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 63. The Wakamiya Maru had been launched in Glasgow in 1900 as the 7,720-ton freighter Lethington and leased to Russia. Early in the Russo-Japanese War she was captured by the Japanese and was taken into service as a navy transport and renamed the Wakamiya Maru. She was leased to the NYK line in 1908 but reentered Japanese naval service in 1913 as an auxiliary and in that capacity operated one or two seaplanes. Inactive for a time after that, she was recommissioned as a seaplane carrier in August 1914 and dispatched to Tsingtao the next month to take part in the reduction of that German base. Damaged by a mine off Tsingtao shortly afterward, she returned to Japan and in 1915 was rerated as an aircraft depot ship, the mercantile suffix Maru being dropped from her name. Retrofitted with a platform over her forecastle in 1920, she was reclassified as an aircraft carrier, and it was from her decks that the first Japanese shipboard takeoff was accomplished. Put on inactive reserve in 1925, the Wakamiya was broken up in 1931. Layman, Before the Aircraft Carrier, 87.

16. NKKS, 1:66; KHI, Kaigun, 13:28.

17. Wada, Kaigun kōkū shiwa, 70.

18. NKKS, 4:25.

19. KKG, 3–4; Wada, Kaigun kōkū shiwa, 93–94.

20. NKKS, 4:33–34; Burdick, Japanese Siege of Tsingtau, 77, 81.

21. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 10.

22. NKKS, 4:49–65; Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 9–10.

23. Burdick, Japanese Siege of Tsingtau, 197.

24. For an analysis of the influence of naval aviation by 1918, see Layman, Naval Aviation in the First World War, 200–205.

25. NKKS, 1:71–72.

26. Ibid., 68–70.

27. Ibid., 75–77.

28. Ibid., 77–78.

29. Ibid., 61–63.

30. Ibid., 56–57.

31. The memorandum itself, Kōkō kaizō ni kansuru shiken [A personal opinion concerning aircraft construction], is reproduced in full in ibid., 106–7.

32. Ibid., 73–74.

33. Ibid., 2:73, 4:653–54; Ikeda, Nihon no kaigun, 2:161.

34. NKKS, 3:147–49.

35. NKK, 288; Ikeda, Nihon no kaigun, 2:161–62; NKKS, 2:653.

36. NKKS, 3:23–32; Ikeda, Nihon no kaigun, 2:160.

37. NKKS, 1:302–12.

38. Ibid., 334–36. Considering the valuable service of the “blimps” of the United States Navy during World War II, the Japanese navy obviously erred in deciding to discontinue the use of airships. But because the Japanese either envisioned the airship in the rather unimaginative role of naval gunfire spotting or exaggerated its potential as an offensive weapon, they never did think through its uses as an element in antisubmarine patrolling, uses that were to be demonstrated so effectively by the Americans in the Atlantic during the war.

39. Ibid., 87–89.

40. Ibid., 78, 80, 86.

41. Wada, Kaigun kōkū shiwa, 264–67; Layman, Before the Aircraft Carrier, 86.

42. Daitō Bunka Daigaku Tōyō Kenkyūjō, Shōwa shakai-keizai-shi shiryō shūsei, 1:96–97; Kuramatsu Tadashi (specialist in Japanese naval policy between the world wars), communication to author, 29 July 1998.

43. SS: Rikugun kōkū no gumbi to unyō, 89–96.

44. Unless otherwise noted, the discussion in this and the next two paragraphs draws heavily on Ferris, “British Unofficial Aviation Mission,” 416–39.

45. The Sempill Mission was not without its difficulties. Particularly frustrating to the British was the lack of enthusiasm conveyed by the base commander, who was not a pilot and had little air experience. Because he could not lead by example, morale sagged. The atmosphere improved greatly upon the appointment as base commander of Lt. Kuwabara Torao, an enthusiastic observer of British naval aviation during World War I and one of the pioneers of Japanese naval air power. Brackley, Brackles, 194; Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 31 March 1998.

46. NKK, 54; NKKS, 2:715.

47. Ikeda, Nihon no kaigun, 2:190, 192; Brackley, Brackles, 173–77.

CHAPTER 2. AIRBORNE

1. Wildenberg, “In Support of the Battle Line,” 1–11.

2. In this and the succeeding paragraph I have been greatly informed by the insights of both Thomas Wildenberg, author of several studies on U.S. naval aviation used in this work, and Comdr. Alan D. Zimm, USN Ret., a longtime student of naval tactics.

3. Extensive discussion of Japanese plans between the world wars for the decisive surface battle is to be found in chaps. 7 and 8 of Evans and Peattie, Kaigun.

4. For a summary of Lanchester’s theories, see ibid., 143–44. For a fuller explication of the “pulsed power” model of firepower, see Hughes, “Naval Tactics,” 11–13. Thomas Wildenberg tends to see the N2 Law as carrying over into the carrier age, the carrier deck load becoming the equivalent of the big-gun salvo. Wildenberg, letter to author, 31 August 1999.

5. An excellent summary of the development of the Japanese aircraft industry before and during World War II is provided by Samuels, Rich Nation, Strong Army, 108–29.

6. Ikeda, Nihon no kaigun, 2:168.

7. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 93, 101; Ferris, “British Unofficial Aviation Mission,” 424.

8. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 161; Sekigawa, Pictorial History, 23–24. For an explanation of the navy’s aircraft designation systems, see app. 7.

9. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 61, n. 37.

10. Ibid., 226.

11. Ibid., 198–99, 224–26.

12. Ibid., 124–25, 135–36.

13. KG, 1:54.

14. The name of this organization, Kaigun Kōkū Hombu, is sometimes translated as Naval Air Headquarters, but as it had an administrative rather than a command function, I believe that the translation used here is more appropriate.

15. NKK, 66.

16. Ikari, Kaigun kūgishō, 1:17–18.

17. These matters are discussed in Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 233–37.

18. KG, 1:451.

19. KKG, 67; Ikari, Kaigun kūgishō, 1:17–24. In 1939 the name of the Air Arsenal was changed to Naval Air Technical Arsenal (Kaigun Kōkū Gijutsushō) and in early 1945 to First Technical Arsenal (Dai-ichi Gijutsushō); the common appellation for the arsenal during the war was the abbreviation Kūgishō. See Mikesh, “Rise of Japanese Naval Air Power,” 110–11, and Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:103–4.

20. Samuels, Rich Nation, Strong Army, provides an illuminating insight into the continuities of Japanese military industrial policy. His discussion of the prototypes policy is on 116–18.

21. Ibid., 121–26.

22. Hone and Mandeles, “Interwar Innovation,” 77–80; Samuels, Rich Nation, Strong Army, 127–28.

23. For an explanation of the Circle plans, see Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, chaps. 8 and 10.

24. NKKS, 2:51; air group total is derived from KG, 1:435.

25. Ōmae, “Nihon kaigun no heijutsu shisō,” 2:37; Ōmae and Pineau, “Japanese Naval Aviation,” 75.

26. KKG, 8–9.

27. Kuwabara, Kaigun kōkū kaisoroku, 117.

28. NKK, 67; KKG, 65–66; Lundstrom, First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat, 455; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 417.

29. NKKS, 2:906–10; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 422; Ōhama and Ozawa, Teikoku rikukaigun jiten, 98.

30. NKKS, 2:163; Agawa, Reluctant Admiral, 86–87.

31. NKKS, 1:93–95.

32. This was only the first of a series of aerial bombardment experiments conducted by the navy on overage Japanese warships, the last being carried out in 1936 on the hull of the Mishima. NKKS, 1:721, 726–29.

33. NKK, 222; NKKS, 1:716–17.

34. NKK, 220; NKKS, 1:749–51.

35. NKK, 220.

36. KS, 23; USSBS, Military Analysis Division, Japanese Air Weapons and Tactics, 55–56.

37. KG, 1:175; NKKS, 1:757; Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:153.

38. J. Campbell, Naval Weapons, 209.

39. Ibid.; NKKS, 1:757–61; KS, 607–8; USNTMJ, Report 0-01-2, “Japanese Torpedoes and Tubes,” Article 2, “Aircraft Torpedoes.”

40. The term “attack” (kōgekki) used after a type number for one of the navy’s bombers meant that the aircraft could be employed either for torpedo attacks or horizontal bombardment, depending upon the kind of ordnance it carried.

41. KG, 1:175.

42. NKKS, 1:756–57.

43. Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:157; Alan D. Zimm, letter to author, 8 August 1992.

44. NKKS, 1:116–17, 204–5, 756; NKK, 221; KKG, 193; Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:153.

45. Van Deurs, “Aviators Are a Crazy Bunch of People,” 96–97.

46. Wildenberg, Destined for Glory, 10–11.

47. Ibid., 30–35, 52–54, 68–70, 73.

48. It should be understood, however, that by the 1930s floatplanes launched from battleships and cruisers had come to be seen not only as having a role in tactical scouting and spotting for friendly surface batteries, but also as carrying out these tasks while driving off enemy fighters. While their pontoons were known to put them at a disadvantage compared with wheeled aircraft in a dogfight, they adjusted their tactics accordingly and devoted rigorous training to perfecting them, an effort that was to pay off well in the early days of the China air war. KKG, 196.

49. Wildenberg, Destined for Glory, 158; NKK, 68; KG, 1:175.

50. NKK, 68; NKKS, 1:683–85.

51. Okumiya, Tsubasa-naki sōjūshi, 114–16.

52. Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:151–52.

53. NKKS, 1:690.

54. P. Smith, Into the Assault, 1–34.

55. Okumiya, Saraba kaigun kōkūktai, 66–67.

56. My use of the term “dive bomber” does not conform to the Japanese terminology of the time. The aircraft used for this purpose were initially called “special bombing aircraft” (tokushu bakugekki) and later were known as “carrier bomber aircraft” (kanjō bakugekki). Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 280, assert that these vaguer designations were applied because the Japanese navy wished to keep secret its progress in the revolutionary tactic of dive bombing. On the other hand, in the United States Navy the terminology for dive bombing was similarly vague at first, and the tactic was referred to as “light bombing,” “strafing with light bombs,” and “diving bombing” before someone coined the term “dive bombing.” See also Tillman, Dauntless Dive Bomber, 4. For an understanding of aircraft terminology in the Japanese navy, see app. 2.

57. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 268–69.

58. Okumiya, Saraba kaigun kōkūtai, 68.

59. NKKS, 1:773–74.

60. NKK, 68, 221.

61. NKKS, 1:79; Ikari, Kaigun kūgishō, 1:103.

62. NKKS, 1:654–55, 660.

63. Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 233.

64. NKKS, 1:661–62; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 233; Reynolds, “Remembering Genda,” 52–56.

65. Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 17 December 1997; Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:119–20; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 342; Mikesh, Zero, 75.

66. Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:112–19.

67. Shibata, Genda Minoru ron, 56.

68. The superiority of the land-based bomber in the 1930s was a widespread phenomenon among the world’s air forces. It was abundantly obvious in the United States Army Air Corps, for example. Once the USAAC developed the Martin XB-10 monoplane bomber, the aircraft’s performance immediately outclassed any pursuit plane then in army service. Wagner, American Combat Aircraft, 101–14. The United States Navy did somewhat better than the Army Air Corps in developing fighter aircraft because of an early decision for radial engines and mechanical superchargers. Frederick J. Milford, letter to author, June 1992.

69. Extremely agile and popular with pilots and ground crews, the A2N was used by acrobatic teams like the “Genda Circus.” The later model, the A4N, had greater speed, increased wingspan, and a more powerful engine, but it was generally rated inferior to the earlier version. By 1937 the A4N, the last biplane fighter to serve with the navy, had proved unable to deal with Soviet-built Chinese planes in the China War and was quickly replaced by the Mitsubishi A5M all-metal monoplane fighter. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 225–26; Polmar, Aircraft Carriers, 80; Munson, Fighters between the Wars, 116–17.

70. NKKS, 1:287–88, 294; KKG, 59.

71. NKKS, 1:666–67. The navy once again adopted the expedient of using fighters as dive bombers when Zeros were used for this purpose in 1943–44, but they were ineffective in this role.

72. Shibata, Genda Minoru ron, 50–62.

73. NKKS, 1:293.

74. Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:104–8; KSS, 386–89.

75. Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:109–10.

76. NKKS, 1:288–90, 294; Caidin, Zero Fighter, 28–30.

77. An attempt to translate the relevant Japanese terminology within this field of aerial activity can be frustrating, given the confusing tendency in the Japanese accounts to use the terms “reconnaissance” (teisatsu), “patrolling” (shōkai), and “searching” (sōsaku) interchangeably. Considerable study of the problem leads me to conclude that “reconnaissance” in the Japanese navy context implies long-distance search, “patrolling” implies defensive scouting activity, and “searching” is a general term that can be applied to either activity.

78. NKKS, 1:780–81.

79. Unless otherwise noted, the information in this and the following two paragraphs is based on Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 31 March 1998.

80. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 162–63, 236–37.

81. This paragraph draws heavily on opinions expressed by Thomas Wildenberg in a letter to the author, 31 August 1999.

82. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 408–10.

83. For a discussion of the development of American flying boats to fill this long-range requirement during this same period, see Miller, War Plan Orange, 175–79.

84. NKK, 68; NKKS, 4:96–97; Thorne, Limits of Foreign Policy, 209.

85. Sekigawa, Pictorial History, 39; NKKS, 4:99–104, 114–15; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 17–18, 24.

86. While the A1N2 seemed to do well against most of the Chinese planes encountered, Japanese pursuit pilots were shocked at its marked inferiority to the Boeing 218, a fact that hastened the development of the Type 90. Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:91–92.

87. NKK, 68.

CHAPTER 3. FLIGHT DECKS

1. A profile, data, and history for each of the Japanese aviation vessels (carriers, seaplane carriers, and seaplane tenders) discussed in this study are provided in app. 4.

2. These matters, as they affected all carrier design in the interwar period, are analyzed by Friedman in Carrier Air Power, 9–23; Chesneau in Aircraft Carriers of the World; and D. Brown in Aircraft Carriers, 2–7.

3. Fukui, Nihon no gunkan, 38; NKKS, 2:190; Jentschura et al., Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 41; Watts and Gordon, Imperial Japanese Navy, 169–71; Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 157–58.

4. SZ, 1:472–73; Nagamura, Zōkan kaisō, 136.

5. SZ, 1:472–73; Snow, “Japanese Carrier Operations.”

6. Originally it had been planned to embark Mitsubishi 1MT1N (Navy Type 10) carrier attack aircraft, but the height—more than 4 meters (14 feet)—of this, the navy’s only triplane, proved too great for the Hosho’s hangar, and the scheme was dropped. SZ, 1:472.

7. Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 157–58.

8. Discussion of these two warships in this and the next six paragraphs is derived principally from the following sources: SZ, 1:473–79; Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 22–24; and Lengerer, “Akagi and Kaga,” pt. 1, 127–39.

9. Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 159.

10. Lengerer, “Akagi and Kaga,” pt. 1, 130.

11. Ibid., 131.

12. In the 1933 and 1934 USN fleet problems, for instance, carriers were caught and “shelled” by “enemy” surface units because they had strayed too close to the opposing force while conducting recovery operations. This starkly illustrated the predicament in which carriers could find themselves because of the continuing need to put the wind over their flight decks. Hone et al., American and British Aircraft Carrier Development, 135.

13. Lengerer, “Akagi and Kaga,” pt. 1, 131.

14. Ibid., 134.

15. Ibid., 136–37.

16. Ibid., 134.

17. Ibid., 138–39; SZ, 1:481.

18. Lengerer, “Akagi and Kaga, pt. 1, 138–39; SZ, 1:481.

19. Lengerer, “Akagi and Kaga,” pt. 1, 136–37; Okada, “Kaga/Akagi,” 86–89.

20. Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 163–64.

21. SZ, 1:479–80; Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 163; Watts and Gordon, Imperial Japanese Navy, 177–78.

22. For a discussion of the impact of this incident upon construction in the Japanese navy generally, see Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 24–45.

23. Evans and Peattie, “Ill Winds Blow,” 70–73.

24. SZ, 1:479–80.

25. Jentschura et al., Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 46, provides diagrams of the several designs for this class. One recent study has asserted that this design was intended as a response to the flight-deck cruisers the United States was then rumored to be building. See Lengerer and Rehm-Takahara, “Japanese Aircraft Carriers Junyō and Hiyō,” pt. 1, 11.

26. The Navy General Staff requirements for the new class included the following: a displacement of 10,500 standard tons; capacity for sixty-eight aircraft; machinery equal to that of the cruiser Kumano; a maximum speed of 35 knots; a range of nearly 8,000 nautical miles at 18 knots; six 12.7-centimeter (5-inch) antiaircraft guns; armor around the magazine to withstand a 20-centimeter (8-inch) shell fired at a range of 12,000–20,000 meters (13,000–22,000 yards); and armor around the boiler sufficient to withstand shellfire from an average-sized destroyer. SZ, 1:480; Fukui, Nihon no gunkan, appendix chart showing aircraft carriers.

27. Fukui, Nihon no gunkan, appendix chart showing aircraft carriers; Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 165–66; SZ, 1:480.

28. Chesneau, Aircraft Carriers, 166.

29. See Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 9–10; Lengerer and Rehm-Takahara, “Japanese Aircraft Carriers Junyo and Hiyo,” pt. 1, 9, 11.

30. In this connection, it is worth noting that horsepower per ton required to achieve a given speed is generally smaller for large ships than for small ones. Thus, large ships require a smaller fraction of their total displacement for propulsive machinery and have more available for other functions. In the case of aircraft carriers, the larger carrier can devote greater displacement to air group storage, ordnance, and aircraft support elements. These matters are discussed in Pugh, Cost of Seapower, 183–212.

31. SZ, 1:536; Watts and Gordon, Imperial Japanese Navy, 182; Dickson, “Fighting Flat-tops,” 16–18.

32. SZ, 1:536.

33. Fukaya with Holbrook, “Shokakus,” 639.

34. At the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Shōkaku and Zuikaku helped to sink the American Lexington. But the Shōkaku was seriously damaged in the process and was under repair at the time of the Midway battle. The Zuikaku was not at the Battle of Midway largely because she lacked a viable air group, since her air group could not prepare the inexperienced pilots assigned to it in time for the Midway operation.

35. Polmar, Aircraft Carriers, 69–70; Dickson, “Fighting Flat-tops,” 15.

36. The navy’s shadow building program using Japanese merchant shipping is discussed in some detail in Lengerer and Rehm-Takahara, “Japanese Aircraft Carriers Hiyō and Junyō,” pt. 1, 12–19.

37. SZ, 1:490–92, 540–41; Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 34, 36, 42; Watts and Gordon, Imperial Japanese Navy, 184–87, 193–94, 199–200, 491–92.

38. SZ, 1:537–39; Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 44; Watts and Gordon, Imperial Japanese Navy, 191–92.

39. SZ, 1:548–49; Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 40; KKG, 89–90; Watts and Gordon, Imperial Japanese Navy, 187–91; Lengerer and Rehm-Takahara, “Japanese Aircraft Carriers Junyo and Hiyo,” pt. 2, 107, 111.

40. Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 31 March 1998.

41. The upper hangar deck was the strength deck of most Japanese fleet carriers, beginning with the Sōryū and continuing through the Hiryū, the Shōkaku-class carriers, and into the Unryū class. The Taiho was a notable exception, with her armored flight deck being the strength deck. D. Brown, Aircraft Carriers, 5, 18, 30.

42. Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 20; Willmott, Barrier, 415; Marder, Old Friends, 1:300; USNTMJ, Report S-06-2, “Report of Damage to Japanese Warships,” 25; author’s conversation, 18 October 1989, with Yoshida Akihiko, an informed authority on the prewar Japanese navy.

43. USNTMJ, Report A-11, “Aircraft Arrangements,” 12.

44. This practice was pioneered aboard the USS Yorktown before the Battle of the Coral Sea. John B. Lundstrom, e-mail to Jon Parshall, 27 March 2000.

45. USNTMJ, Report A-11, “Aircraft Arrangements,” 20–23.

46. Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 20; Willmott, Barrier, 415; Marder, Old Friends, 1:300; USNTMJ, Report S-06-2, “Report of Damage to Japanese Warships,” 25; author’s conversation with Yoshida Akihiko, 18 October 1989.

47. Lengerer, “Akagi and Kaga,” pt. 1, 130.

48. Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 165; Snow, “Japanese Carrier Operations.” This information corrects a serious error in Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 324, which implies that Japanese carriers had no crash barriers.

49. Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 135–40; Friedman, U.S. Aircraft Carriers, 139. As Friedman notes, this capability seems bizarre to the modern reader, yet it represented a means of ensuring that a carrier could at least land its air complement in the event of a bomb hit aft. The ability to conduct landing operations over the bow had been a feature of early American carriers, and it was an important formal design consideration for the Essex-class carriers, which (unlike their earlier counterparts) could steam long distances going astern without causing damage to their machinery. Fore-mounted arresting gear was not removed from U.S. carriers until 1944. The Japanese mounted such gear on many of their fleet carriers, including the late-war Taiho-, Unryū-, and Shinano-class vessels.

50. Popham, Into Wind, 143.

51. Japanese carriers were supposed to maneuver independently when launching and recovering aircraft, except in those cases where enemy naval or air bases were within 300 miles; ATIG Report no. 1, 2. However, it is unclear whether this practice was strictly followed under combat conditions, such as the Battle of Midway. I am grateful to John B. Lundstrom for drawing my attention to the ATIG material. The reports cited were largely based on interviews with naval officers who had responsible positions aboard Japanese carriers at Midway, including captains Aoki Taijirō, who commanded the Akagi; Amagai Takahisa, air officer of the Kaga; and Kawaguchi Susumu, air officer of the Hiryū.

52. Okumiya, Saraba kaigun kōkūtai, 72; Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 172; Fuchida and Okumiya, Midway, 135. On occasion, there were apparently takeoff cycles of as little as ten seconds. ATIG Report no. 2, 2.

53. ATIG Report no. 1, 3.

54. An underdeck air-propelled catapult design was apparently developed in 1935 but was not adopted owing to its complexity and to the belief at the time that such gear was unnecessary. In the latter half of the Pacific War, this lack of foresight would hamper Japanese carrier operations using heavier aircraft. ATIG Report no. 2; ATIG Report no. 7, 1.

55. ATIG Report no. 1, 5; ATIG Report no. 2, 2; ATIG Report no. 5, 3.

56. ATIG Report no. 1, 5; ATIG Report no. 2, 2; ATIG Report no. 5, 2.

57. ATIG Report no. 5, 3.

58. Snow, “Japanese Carrier Operations”; Hasegawa, Nihon no kōkūbōkan, 167; USNTMJ, Report A-11, “Aircraft Arrangements,” 15–18.

59. ATIG Report no. 2, 2.

60. ATIG Report no. 5, 3.

61. In the early stages of the Pacific War, aircraft arresting hooks were controlled by the pilot (in single-seat aircraft) or the observer crewman (in multiseat aircraft). However, later in the war the hook apparatus was modified so that the deck crew was made responsible for releasing the hook. This was done because the decline in the quality of aircrew training had led to an increase in deck accidents due to premature hook release. ATIG Report no. 3, 1.

62. Each arresting wire was controlled by enlisted crewmen, whose stations were staggered port and starboard down the length of the flight deck. All crash barriers were controlled by a single enlisted man stationed on the port side of the flight deck, who received signals from the air operations officer to raise and lower the barrier. ATIG Report no. 2, 2.

63. Okumiya, Saraba kaigun kōkūtai, 78.

64. Typical elevator cycles to the lower hangar deck and back were around forty seconds for the Shōkaku, including unloading time. Dickson, “Fighting Flat-tops,” 18. However, older carriers, such as the Akagi and Kaga, had slower elevators.

65. Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 13–15; Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, Miracle at Midway, 214–15, 264. I am also grateful for the insights of Thomas C. Hone and Mark A. Campbell on these matters.

66. Okumiya, Saraba kaigun kōkūtai, 74. In order of frequency, the most common landing accidents on Japanese carrier flight decks were (1) missing the deck astern (too low); (2) damaged landing gear from hard landings; (3) barrier crashes; (4) hitting the wing against the carrier island; and (5) going over the side. At night, mishaps 2 and 4 were apparently the most prevalent. ATIG Report no. 1, 5.

67. The First Carrier Division (Rear Adm. Takahashi Sankichi commanding) initially consisted of the Hōshō and Akagi, with the Kaga joining the division in November 1929.

68. Sekigawa, Pictorial History, 29; NKKS, 1:203–4.

69. Ōmae, “Nihon kaigun heijutsu shisō,” 1:47; NKKS, 1:114, 203–4; Genda, “Evolution,” 23. Thomas Wildenberg points out that in the United States Navy such carrier-vs.-carrier scenarios had been part of the Fleet Problems since 1929. Wildenberg, letter to author, 31 August 1999.

70. The Battle Instructions were a set of principles for fleet maneuvers and tactics that represented the heart of tactical doctrine in the Japanese navy and were thus among its most closely guarded secrets. The instructions were revised five times: in 1910, 1912, 1920, 1928, and 1931. See Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 550, n. 44.

71. Ōmae, “Nihon kaigun heijutsu shisō,” 1:51; KKG, 48–49; KG, 1:135–36.

72. I refer to the concept of a preemptive strike at several points in this chapter. Because of the inadequacy of the Japanese documentary record, it is impossible to say with any precision just when the Japanese navy first incorporated this concept into its doctrine, though it certainly appears in the Naval Staff College study of November 1936 mentioned later in this chapter. My discussion of the navy’s thinking on carrier strikes in the mid-1930s is drawn almost entirely from KKG, 202–4, which in turn is drawn from the recollections of former IJN commander Tsunoda Hitoshi,† whose career was almost entirely in naval aviation. After the war Tsunoda was on the research and editorial staff of the War History Institute of the Japanese Self-Defense Agency, a position that would have given him access to whatever relevant documents exist concerning Japanese naval doctrine; this fact, added to his long naval air service, gives his views considerable authority.

73. Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 42–43; KG, 1:176–78; KS, 502.

74. KKG, 50. While this source is not specific on the matter, Thomas Wildenberg has pointed out that a doctrine that called for nearly simultaneous attacks on enemy carriers and battleships indicates that the Japanese navy assumed that American carriers would be operating closely with the battleship main body. He further suggests that this assumption in turn may have led the Japanese navy to believe that it did not need to develop any sophisticated reconnaissance arrangements, since such a large concentration of fleet units could be easily discovered. Wildenberg, letter to author, 31 August 1999.

75. Dickson, Battle of the Philippine Sea, 221; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 9.

76. When operating with a protecting cruiser force, the actual position of carriers in relation to the cruiser force and the main body of the fleet was, of course, determined in part by the direction of the wind for the launching and recovery of aircraft. For a discussion, illustrated by diagrams, of the actual positioning of Japanese carriers in various cruising formations, see Fioravanzo, “Japanese Military Mission,” 26–29.

77. NKKS, 1:205; Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 54; Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 42–43.

78. KKG, 202–3.

79. NKKS, 1:205–6; Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 43–46.

80. KG, 1:169.

81. KKG, supplement chart no. 2; Larkins, U.S. Navy Aircraft, 243–44.

82. John B. Lundstrom, letter to author, 15 March 1997.

CHAPTER 4. SOARING

1. NKKS, 1:101.

2. Ibid., 113.

3. NKK, 69.

4. Agawa, Reluctant Admiral, 104–5; Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 100–101.

5. Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 175; Bueschel, Mitsubishi/Nakajima G3M1/2/3, 4–5.

6. The noted British naval historian Stephen Roskill, for example, has written of the Japanese navy’s “freedom from the controversies which so long plagued naval aviation in Britain.” Roskill, Naval Policy between the Wars, 1:531.

7. Genda, “Tactical Planning,” 46–47.

8. Ko Ōnishi Takijirō Kaigun Chūjō Den Kankōkai, Ōnishi Takijirō, 38–40, 50; NKKS, 1:116.

9. NKKS, 1:119–20; Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:137–47.

10. Quoted in KKG, 48.

11. Ibid.

12. NKKS, 1:123–24.

13. Agawa, Reluctant Admiral, 93.

14. NKKS, 1:124–25.

15. KKG, 74–79.

16. I realize that my use of the term “medium bomber,” in the context of the G3M and its successor the G4M, will upset some purists in correct Japanese aircraft terminology. The term does not translate exactly from the common Japanese rikkō appellation, and admittedly the Japanese developed no operational heavy bomber with which to compare its size. Nevertheless, for a Western audience, the term “medium bomber” for the G3M seems more appropriate, since it brings to mind the Mitchell B-25 and the Marauder B-26, which were also twin-engined and which were roughly comparable in size. It is true, of course, as Osamu Tagaya points out (letter to author, July 2000), that the navy’s original purpose in the design of the G3M was to develop a land-based long-range aircraft that could deliver torpedo—not bombing—attacks against a distant enemy fleet. Yet despite a few dramatic exceptions early in the Pacific War, over the entire operational span of both the G3M and the G4M, these aircraft were used primarily for bombing missions.

17. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:38–47; NKS, 1:142; Francillon, Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers, 41–45.

18. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:51–52, 115–16.

19. Bueschel, Mitsubishi/Nakajima G3M1/2/3, 4–5. In the development of the G3M1 a serious controversy had arisen over its armament. Specifically, the question was whether to put a machine gun in the nose of the aircraft, along with a position for an observer who would fire it, or whether to omit the gun from the nose assembly and place the observer behind the pilot. For easier communication between the pilot and observer, the second arrangement was eventually adopted (perhaps because the observer was often the commander of the aircraft), but this left a dead space for defensive fire forward. Undetected in peacetime exercises, this was to prove a dangerous defensive weakness in combat. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:45–47.

20. NKKS, 4:26.

21. NKS, 1:132, 134; Horikoshi and Okumiya, Reisen, 54–55; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 342–43.

22. NKKS, 1:297–98.

23. NKKS, 3:412, 414; NKS, 1:128–34; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 342–43.

24. Horikoshi, Eagles of Mitsubishi, 19–23; Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 173–74; NKKS, 1:293; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 342–43; NKKS, 3:414; Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:122–26.

25. NKKS, 1:293; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 342, 345.

26. Leary, “Assessing the Japanese Threat,” 274.

27. NKS, 1:156; Horikoshi, Eagles of Mitsubishi, 3–7; Caidin, Zero Fighter, 36–37.

28. Horikoshi, Eagles of Mitsubishi, 48–51; Caidin, Zero Fighter, 37–41; USSBS, Military Analysis Division, Japanese Air Weapons and Tactics, 10–12.

29. Horikoshi, Eagles of Mitsubishi, 34–46; Thompson, “Zero,” 33–34.

30. NKS, 1:156–66; Caidin, Zero Fighter, 41, 48–49; Bueschel, Mitsubishi A6M1/2, 4. The most comprehensive and detailed study of the Zero in English is without doubt Robert Mikesh’s Zero, but perhaps the most insightful analysis is to be found in Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, which discusses the aircraft’s strengths and weaknesses at great length. There is, of course, a wealth of information on the genesis of this aircraft in Eagles of Mitsubishi by Horikoshi, as well as in Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, which is a translation and adaptation of the original work, Reisen, by Horikoshi and Okumiya. The Squadron/Signal publication of Shigeru Nohara’s A6M Zero in Action contains numerous and interesting schematics and line drawings of the many models of the aircraft as well of its various components.

31. In this connection, Gary Boyd, a historian for the United States Air Force, has written a highly interesting monograph in which he argues that the design of the Zero was largely based on the Chance-Vought V-143 fighter plane. The V-143 had been turned down by the United States Army Air Corps but was purchased from that company by Mitsubishi in 1937, about the time Horikoshi and his team began design work on the Zero. Boyd asserts that the Horikoshi design adhered closely to the V-143 across an array of configurations and equipment. But Boyd’s evidence is largely circumstantial, and he admits that Japanese documentation concerning the V-143 is completely lacking. Boyd, “Vought V-143,” 28–37.

32. Thompson, “Zero,” 32.

33. Unless otherwise indicated, this and the following three paragraphs are based largely on Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 199–212.

34. Horikoshi, Eagles of Mitsubishi, 139.

35. See app. 8 for a discussion of the nature and significance of the development of the principal aircraft engines developed by the Japanese navy.

36. KKG, 195; Thompson, “Zero,” 32; Spick, Fighter Pilot Tactics, 86. The Zero carrier fighter went through eight major model changes from its adoption to the end of the Pacific War. A floatplane version was built by Nakajima during the war. For details, see Mikesh, Zero, 88–97, and Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 362–77.

37. NKS, 1:176–82; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 317–19, 320–27, 388–95, 417–22; NKS, 3:121–24, 126–34; Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, July 2000.

38. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 211.

39. Francillon, Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers, 21–29; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 271–75; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 218–19.

40. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 218–19.

41. NKS, 5:161–65; Francillon, Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers, 11–16.

42. NKS, 5:166; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 412–14.

43. This and the next two paragraphs are based largely on Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 212–15, 218; NKS, 1:166–68, 172–75; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 378–79; and Francillon, Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers, 45–49.

44. NKS, 1:168–75.

45. Osamu Tagaya believes that the G6M1 was originally developed as an escort for the projected G4M, not for the G3M as asserted in Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 380. Tagaya points out that the superiority in cruising speed of the G4M over the G3M was such that no aviation professionals would have considered the two aircraft an effective match. Indeed, in the early days of the Pacific War when the two types of aircraft were used together for bombing attacks on the Philippines and Singapore from bases near Saigon, the G3Ms were obliged to take off one hour ahead of the G4Ms. The latter, with their faster cruising speed, would then automatically catch up with the G3Ms just as they approached the target, allowing the two types to deliver combined attacks. Tagaya, letter to author, August 2000.

46. Lundstrom, First South Pacific Campaign, 66–67.

47. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 307–12. Some examples of the aircraft’s range and ruggedness: flying from Wotje Atoll in the Marshalls, an H8K carried out a night bombing of Hawai’i; flying across the Bay of Bengal, another reconnoitered the port of Columbo, Ceylon, engaged a B-17 Flying Fortress, and shot it down; and, in a tangle with a Curtiss P-40 fighter plane, an H8K drove off the attacker and returned safely to base with seventy bullet holes in the fuselage. NKS, 3:106–16.

48. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 358–61; NKKS, 3:498–500.

49. Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 277–79.

50. NKS, 5:184–88; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 429–32, 454–55; Francillon, Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers, 28–40.

51. USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 1.

52. Ibid.

53. TS, Shōkō seisaku shi, 18:427; Mikesh and Abe, Japanese Aircraft, 262–63.

54. USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 7; TS, Shōkō seisaku shi, 18:427.

55. USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 7.

56. TS, Shōkō seisaku shi, 18:431; USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 27.

57. TS, Shōkō seisaku shi, 18:436–37.

58. As measured by an efficiency index worked out by the Aircraft Resources Control Office of the U.S. War Production Board during World War II. USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 27–28.

59. TS, Shōkō seisaku shi, 18:438; USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 22–23; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 204.

60. USSBS, Economic Studies, Japanese Aircraft Industry, 7; TS, Shōkō seisaku shi, 18:436.

61. Krebs, “Japanese Air Forces,” 233, n. 11.

62. KKG, 208–9.

CHAPTER 5. ATTACKING A CONTINENT

1. Tsutsui, “Shina jihen,” 19, 25.

2. There is as yet no comprehensive and authoritative English-language study of the navy’s air war in China. Until such a work appears, the reader will have to make do with a slender and popular account, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: Air War in China, 1937–1941, by Ray Wagner.

3. The best English-language overview of the outbreak of Japanese hostilities with China is provided in Hata, “Marco Polo Bridge Incident.”

4. Kusaka, Ichi kaigun shikan no hanseiki, 266.

5. NKKS, 4:261–62.

6. KKG, 113–14; Nagaishi, Kaigun kōkūtai nenshi, 18–19.

7. NKKS, 1:283.

8. NKKS, 4:191–95; U.S. Department of the Army, Japan Monographs no. 166, 21–23; Caidin, Ragged Rugged Warriors, 58–65.

9. Izawa, Rikkō to Ginga, 43–46.

10. Ibid., 78–79.

11. I base this opinion on an incident in Takahashi et al., Kaigun rikujō kōgekki-tai, 212–13, which, though dealing with Japanese medium-bomber operations in the Pacific War, would seem to hold true for similar operations in the China War. I am indebted to Osamu Tagaya for this reference.

12. Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 17–19, 30–31.

13. NKKS, 4:266–67.

14. Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, 12; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 562.

15. NKKS, 4:264–70.

16. Ibid., 269–72.

17. Ibid., 271–72.

18. KKG, 115.

19. U.S. Department of the Army, Japan Monographs no. 166, 27–30, 38–39.

20. NKKS, 4:265–66; NKS, 1:156.

21. NKKS, 4:262.

22. Ibid., 443–44.

23. Nakayama, Chūgoku-teki tenkū, 241. I am indebted to Osamu Tagaya for bringing this source and reference to my attention.

24. My narrative here is based on a balancing of conflicting assertions made in NKKS, 1:235–38, and Hsu and Chang, History of the Sino-Japanese War, 268–69.

25. NKK, 94; Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, 27.

26. Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 426.

27. Although internationally the term “ace” has been applied to pilots who have shot down five or more aircraft, the Japanese services had no tradition of recording kills by individual pilots. On their part, Hata and Izawa provide biographies only of those pilots who had eleven or more victories to their credit. Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, ix, 344.

28. KSS, 392. As Osamu Tagaya has noted, it was during these years that Japanese pilots first began to encounter tactics that would neutralize and overcome their cherished dogfighting style. In the skies over western Manchuria during the heavy aerial combat of the Nomonhan “Incident” of 1939, Soviet I-16 fighter planes learned to avoid swirling dogfights with the more maneuverable Japanese Army Type 97 fighter (similar to the Navy A5M) and began to use “hit-and-run” tactics with great success. In a harbinger of what was to come for the Japanese navy in the Pacific War, army pilots found it difficult to counter this tactic, and their losses began to mount. Tagaya, communication to author, 1 February 2000.

29. Most fighter units in the Japanese navy used the three-plane shōtai until late 1943, a source of wide criticism by students of air combat history. The charge has been that, like the RAF “vic,” which it supposedly resembled, it was vulnerable to attack and led to collisions between its aircraft. But John B. Lundstrom points out that the Japanese shōtai was nothing like the constricted “vic” that, beginning in the Spanish civil war, was tried and rejected by every major European air force. The Japanese flew a much looser formation, often line astern or staggered, which reduced the danger of collision and allowed for much greater lookout on the part of the wingmen. In 1941–42, very rarely was a formation of Japanese navy fighters surprised, which was certainly not true of the RAF. John B. Lundstrom, letter to author, 10 January 1994.

30. Izawa, Rikkō to Ginga, 57–61; SS: Chūgoku hōmen, 1:522–23.

31. Caidin, Ragged Rugged Warriors, 72.

32. NKK, 94; NKKS, 4:387–88; KKG, 115–16; Caidin, Ragged Rugged Warriors, 106–7; Cornelius and Short, Ding hao, 87–88.

33. On the problem of exaggerated Japanese kills, see USSBS, Military and Naval Intelligence Division, Japanese Military and Naval Intelligence, 24, and Hsu and Chang, History of the Sino-Japanese War, 269.

34. In March 1938 the Kisarazu and Kanoya naval air groups were returned to their home bases in Japan and were placed under the command of the Combined Fleet for training and operational purposes, while the Thirteenth Air Group was reconstituted as a purely medium-bomber unit and sent to China for operations there. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:112.

35. KKG, 116; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 101; Caidin, Ragged Rugged Warriors, 99.

36. NKK, 95.

37. Bueschel, Mitsubishi/Nakajima G3M1/2/3, 8.

38. NKKS, 1:478; Bueschel, Mitsubishi/Nakajima G3M1/2/3, 8.

39. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:160–61; KKG, 117.

40. Caidin, Ragged Rugged Warriors, 99–100.

41. NKKS, 4:552–63; NKK, 95; Caidin, Ragged Rugged Warriors, 99–100, 151–53; Sekigawa, Pictorial History, 70.

42. NKKS, 4:368–69, 510–11.

43. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:154–62.

44. NKKS, 4:563; Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:164, 166.

45. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:166–67.

46. These were the Mitsubishi C5M2 (Type 98) reconnaissance planes, a navy version of a single-engined army aircraft that as a civilian plane had set a speed record for a Japan-to-Britain flight in 1937. Equipped with special radio and camera equipment, the plane was used for deep penetrations into Chinese territory. NKS, 1:152, 154; Francillon, Japanese Aircraft, 152–53.

47. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:161–71.

48. Yokoyama, Aa reisen ichidai, 74.

49. Ibid., 80; Horikoshi and Okumiya, Reisen, 155.

50. Yokoyama, Aa reisen ichidai, 82–88; Horikoshi and Okumiya, Reisen, 155–58. Once again, my tabulation of losses on each side is a composite of Japanese and Chinese accounts: NKKS, 4:560, 571; Mikesh, Zero, 39; Hsu and Chang, History of the Sino-Japanese War, 512; and a communication from D. Y. Louie, an amateur specialist in the air war over China, citing a memoir of a Chinese pilot who participated in the engagement.

51. There remains a good deal of uncertainty as to when reliable information concerning the Zero first reached the United States. William Leary has asserted that in the autumn of 1940 the Chinese captured a Japanese light-bomber pilot stationed at Hankow who related to his Chinese captors considerable information about the Zero that he had gleaned from Zero pilots also based at Hankow. This information was supposedly passed on to the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington in November 1940. Leary goes on to state that additional data on the Zero arrived in Washington in late June 1941, again from the Chinese, who, it is claimed, shot down a Zero, recovered its wreckage fairly intact, and from it compiled a detailed technical report that confirmed the intelligence passed to Washington the previous November. Leary concludes that the United States had early and accurate information on the Zero before the Pacific War yet through complacency, chauvinism, and ignorance simply disbelieved it. Leary, “Assessing the Japanese Threat,” 272–77.

One does not know what to make of the recollection of Stephen Jurika, former assistant naval attaché in Tokyo in the years immediately prior to the Pacific War, who in later years claimed that in 1940 he actually sat in the cockpit of a Zero that was on display at the Haneda International Airport. Jurika asserted that the serial plate inside the cockpit was printed in English and provided important information about the aircraft, such as the weight of the aircraft and the horsepower of its engine. Jurika papers, Hoover Archives, Stanford University, file 10, 348. This account is relayed without comment by John Prados in his Combined Fleet Decoded. Given the Japanese obsession with military secrecy and the fact that this was one of the Japanese navy’s newest and most valuable technologies, Jurika’s claim is incredible.

52. KKG, 119–20; Caidin, Zero Fighter, 54–58.

53. NKK, 95; Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:173; KKG, 120.

54. NKK, 95.

55. Ibid.

56. SS: Chūgoku hōmen kaigun sakusen, 2:276–78.

57. KKG, 121–22. In this summary of losses I have set aside those caused by air accidents in Japan due to accelerated and intensified training. While I have no figures on the number of fatalities caused by these accidents, the number of accidents themselves jumped from 22 in 1937 to 206 in 1941. It is impossible to say whether the accident rate was increasing, or whether the higher number just reflects the larger number of trainees. KKG, 145.

58. Overy, “Air Power,” 9.

59. NKK, 95.

60. KHI, Kaigun, 13:70; KKG, 88.

61. KHI, Kaigun, 13:70; KKG, 89; Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 46–47.

62. KHI, Kaigun, 13:71; KKG, 89.

63. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:41.

64. Of the 150 fighter aces in the Japanese navy listed in Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, fully one-third achieved their first victories in air combat over China, 1937–41.

65. KKG, 194.

66. Ōmae, “Nihon kaigun no heijutsu shisō,” 1:51–52; KKG, 189, 192. Although the navy’s air groups proved in the China War that they could cooperate effectively with the army in land operations, army air groups were almost completely ineffective in operations at sea, for which they had very little training. When the Pacific War began, this weakness was glaringly revealed and stands in sharp contrast to the reasonably effective long-range, overwater operations of the United States Army Air Force in the Pacific. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:113–14.

67. Iwaya, Chūkō, 1:161.

68. KKG, 88, 142–43; NKK, 221.

69. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 17, 194–99, 327, 412–13.

70. KSS, 394, 397–98.

71. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 17.

CHAPTER 6. FORGING THE THUNDERBOLT

1. Because of their somewhat more advanced educational qualifications, these recruits, now designated Kō- (A-) category students within the Yokaren system, would have to undergo only twelve to fourteen months of general training, instead of the two and a half years required of the primary-school graduates under the old system. Some of the latter type of students were still recruited by the navy under the same conditions as formerly, but they were now designated to be Otsu- (B-) course students. In 1940, recruits brought into the naval air service from noncommissioned ranks under the old Sōren (Pilot Trainee) system were placed in what was now called the Hei- (C-) course category. KKG, 105, 152; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 410.

2. Wildenberg, Destined for Glory, 87–88.

3. Lundstrom, First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat, 454–55; Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 265; Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 31 March 1998.

4. Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 417.

5. Lundstrom, First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat, 456; USSBS, Military Analysis Division, Japanese Air Power, 34.

6. KKG, 152; USSBS, Military Analysis Division, Japanese Air Power, 35.

7. KKG, 13; KSS, 361–68.

8. KSS, 364.

9. Kusaka, Rengō kantai, 318.

10. Sakai, with Caidin and Saito, Samurai, 10, 13–15, 17.

11. Ōmae, “Nihon kaigun no heijutsu shisō,” 2:40; Marder, Old Friends, 1:315–16.

12. Van Fleet, United States Naval Aviation, 382.

13. Accurate figures for both sides are elusive. For the Japanese side, KG, 2:202, states that there were about seven thousand total aircrew in December 1941. The most authoritative postwar source on Japanese naval aviation, KKG, asserts that no reliable records providing such statistics for that period survived the Pacific War. Fragmentary evidence from an official record kept by the Naval Aviation Department indicates that in 1940 the navy had 3,371 pilots, of whom 2,516 were assigned to operational air groups and 855 were in the pipeline, attached to training air groups. The same report notes that in March 1941 there was a “shortfall” in navy pilots of 20 percent, but it gives no target figure (KKG, 106). I estimate that even if the navy had added another one thousand pilots by December 1941, it is unlikely that there would have been more than thirty-five hundred operational pilots in the Japanese navy by that time. Of these, of course, a sizable number, having just completed flight training, would not have been combat-ready. Thus the figure of nine hundred for carrier aviators suggested by James Sawruk, who has spent considerable time estimating aircrew figures for both navies. Sawruk, communication to author, 7 April 1998.

For the American side, Furer, Administration, 385, drawing on an unpublished history of U.S. naval administration in World War II, states that as of 1 December 1941, there were 6,206 naval aviators in the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard (not including trainees). But more authoritatively, Van Fleet, United States Naval Aviation, 461, asserts that there were somewhat fewer than eight thousand active-duty pilots in the United States Navy and Marine Corps in December 1941.

14. Another source of tactical inspiration for the navy’s fighter squadrons was the information brought back by a small number of naval air officers who were detached to observe the fierce air combat between air units of the Japanese army and the Soviet air force along the border between Mongolia and western Manchuria in the spring and summer of 1939. NKKS, 4:677.

15. Unless otherwise noted, this and the next paragraph are based on the authoritative discussion of Japanese fighter tactics in Lundstrom, First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat, 486–89.

16. Spick, Fighter Pilot Tactics, 86; NKKS, 1:678.

17. KKG, 195.

18. John B. Lundstrom, letter to author, 6 January 1994; Cook and Cook, Japan at War, 139; Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 31 March 1998.

19. These points were made to the author by Frederick J. Milford, 6 April 1993.

20. NKKS, 1:79.

21. KKG, 186; U.S. War Department, Handbook on Japanese Military Forces, 315.

22. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 163.

23. KKG, 198.

24. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, Miracle at Midway, 373. It is possible to chart the Japanese navy’s fluctuating emphasis on fighter aircraft by noting the composition of carrier air groups at different points in time. Off Shanghai in 1932, the Kaga’s air group consisted of twenty-four fighters and thirty-six attack aircraft. In the mid-1930s it consisted of twelve fighters and sixty dive and torpedo bombers, and for the Pearl Harbor strike it comprised eighteen fighters and fifty-four dive and torpedo bombers.

25. KKG, 189–90.

26. Okumiya, Tsubasa-naki sōjūshi, 190.

27. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 160–61. In this connection, some fragmentary but instructive data remains from the Combined Fleet bombing exercises of 1939. During daylight, on a target moving at 14 knots, level bombing runs by land-based G3Ms from heights of 400–4,100 meters (1,300–13,000 feet) resulted in 18 hits out of 139 bombs dropped, or 12 percent; level bombing runs by carrier-based attack planes from heights of 1,000–3,000 meters (3,000–10,000 feet) resulted in 17 hits out of 152 bombs, or 11.2 percent; dive-bombing runs by carrier dive bombers from heights of 350–700 meters (1,000–2,000 feet) resulted in 66 hits out of 123 bombs, or 53.7 percent; and torpedo attacks by thirty carrier attack planes (accompanied by both dive bombers and land-based twin-engined bombers) resulted in 49 hits out of 74 torpedoes launched, or 76 percent (but because some of the torpedoes were oxygen-driven, their wakes could not be traced). KKG, 144. Of course, it must be noted that exercise conditions are rarely good indices of combat results, and that in the Pacific War, Japanese bombing attacks rarely achieved the percentages given above.

28. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 259–60.

29. Okumiya, Saraba kaigun kōkūtai, 147–50.

30. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 161–63, 268–69, 323.

31. KKG, 190; J. Campbell, Naval Weapons, 215. According to John De Virgilio, a specialist in the ordnance used by the Japanese in the Pearl Harbor attack, the Type 99 No. 80 Mk-5 bomb was a reshaped 41 centimeter (16-inch) AP naval shell normally used for the main batteries of the battleships Nagato and Mutsu. It was produced by machining the shoulders back to make the nose of the shell more pointed for better penetration. It was then machine-tapered from just above the midbody to the base of the shell for better aerodynamics. The internal cavity of the shell, which contained the bursting charge, was widened slightly by machine-shaving. This process was hard on the heavy machinery doing the work, and for that reason only 150 of these bombs were produced before the machinery broke down. De Virgilio, e-mail to Jon Parshall, 20 May 1998.

32. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 513; KKG, 191.

33. NKKS, 1:693–94.

34. In directing training of dive bomber units at Kasanohara, near Kanoya in southern Kyūshū, Comdr. Egusa Takashige gained approval for bomb release as low as 450 meters (about 1,500 feet) in order to increase the chances of a direct hit. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 271.

35. NKKS, 1:694; KKG, 192; CincPac/CincPOA, “Know Your Enemy,” 21.

36. CincPac/CincPOA, “Know Your Enemy,” 19, 21–22.

37. KKG, 193; NKKS, 1:707–8. Prior to the outbreak of the Pacific War, the navy considered using an entirely new bombing technique—skip bombing (hanchō bakugeki)—by which the bombing aircraft actually bounced their bombs off the water and onto the sides or decks of enemy ships. Apparently it was not practiced by the navy, which used it only once, in February 1942, when G3M bombers of the Genzan Air Group based at Kuching, Borneo, employed it with some success against Allied merchant ships trying to flee Singapore Harbor. However, it was used by American army bombers with devastating effect against Japanese shipping in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in March 1943. NKKS, 1:714–15.

38. KG, 1:175.

39. NKK, 222–23.

40. KKG, 194; NKKS, 1:764; Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 49.

41. KKG, 194; KS, 611; USSBS, Military Analysis Division, Japanese Air Weapons and Tactics, 56–57; CincPac/CincPOA, “Know Your Enemy,” 22–23.

42. Recent studies have tended to downplay the influence of the Taranto attack on the Japanese plans for Pearl Harbor. See, for example, Marder, Old Friends, 1:315, and Chapman, “Tricycle Recycled,” 276–77, 291–92.

43. KS, 621–26; NKKS, 1:765–66.

44. NKKS, 1:757–61; KS, 607–8; USNTMJ, Report 0-01-2, “Japanese Torpedoes and Tubes,” Article 2, “Aircraft Torpedoes.”

45. Yamamoto Teiichirō, Kaigun damashii, 165–69; Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 104–6, 159–60, 270–71, 320–22; De Virgilio, “Japanese Thunderfish,” 61–68; Genda Minoru’s analyses of the Pearl Harbor operation in Goldstein and Dillon, Pearl Harbor Papers, 17–44.

46. Marder, Old Friends, 1:443–44.

47. Initially the navy attempted to settle on the single best aerial offensive tactic, and to this end the Yokosuka Naval Air Group devoted intensive study to the relative merits of torpedo and dive bombing. Not surprisingly, its staff reached the conclusion, around 1940, that each tactic had its advantages, and thus the staff eventually confirmed the value of each. NKKS, 1:773–74.

48. Ibid., 707; KKG, 193, 203; Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 47–48.

49. KG, 1:136–37, 142.

50. NKKS, 4:262.

51. Genda, “Evolution,” 24.

52. NKKS, 1:42, 153–54, 189–90; Genda, Kaigun kōkūtai, 1:144.

53. Polmar, Aircraft Carriers, 131–32; Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 56.

54. Genda, Shinjuwan sakusen, 24.

55. The position of the carrier fleet, vis-à-vis its cruiser escorts and the main body of capital ships, was to depend largely on the strength and direction of the wind. Fioravanzo, “Japanese Military Mission,” 26–29.

56. Genda, Shinjūwan sakusen, 62; Polmar, Aircraft Carriers, 132; Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 56.

57. While Genda’s claim to the authorship of this important tactical innovation may indeed be valid, it is worth noting that it rests entirely on his own account. One finds no corroboration of his assertion in two of the most authoritative works on Japanese naval aviation, KKG and NKKS. For his part, Yoshida Akihiko is skeptical of Genda’s claim and believes that the innovation of the Japanese box formation, like all developments in the navy’s operational doctrine, was probably the result of discussions, over time, among a number of leading naval officers—in this case, men like Genda, Yamamoto, Ōnishi, Kusaka Ryūnosuke, Yamaguchi Tamon, Ozawa Jisaburō, and Miwa Yoshitake. Yoshida, letter to author, 6 November 1990.

58. Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 102.

59. Ibid., 101–2; Ozawa Teitoku Den Kankōkai, Kaisō no Teitoku Ozawa, 20–22.

60. Within a few months the reorganization led to a renumbering of the navy’s air units whereby all aircraft carrier divisions were numbered from one to ten, seaplane carrier divisions from eleven to nineteen, and air flotillas from twenty to twenty-nine. KKG, 149–50.

61. Ibid., 149–50.

62. KKG, 207; Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, 101–2, 106.

63. Polmar, Aircraft Carriers, 132; Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 56. At the Battle of the Coral Sea, the first fleet action that pitted carrier against carrier, the Japanese had only two fleet carriers at hand, not the assembled assets of the First Air Fleet.

64. KKG, 204.

65. Ibid., 203–4; NKKS, 1:704–5.

66. Genda, “Evolution,” 27.

67. Dickson, Battle of the Philippine Sea, 25.

68. This and the next two paragraphs are based on KKG, 185–89, and NKKS, 1:27–28.

69. KKG, 186.

70. Dallas Isom, using SS (Senshi sōsho) documentation, takes sharp exception to the accepted wisdom that Japanese aerial reconnaissance was sloppy at Midway. He argues that cloud cover had much to do with the Japanese failure to discover the American carrier force, and that the causes of the disaster to the Japanese fleet lie elsewhere. Isom, “Battle of Midway,” 87–94.

71. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 555.

72. Morison, New Guinea and the Marianas, 316–17.

73. KKG, 205.

74. Unless otherwise noted, my understanding and analysis of fleet air defense as it existed in December 1941 derive directly from ibid., 205–6.

75. Even after the advent of radar, of course, its effective coordination with fleet air defense took time. Moreover, the damage wrought by Japanese kamikaze aircraft late in the Pacific War demonstrated that it was impossible to defeat a determined air attack completely. John B. Lundstrom, letter to author, 16 August 1994.

76. Spick, Fighter Pilot Tactics, 90; Lundstrom, First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat, 228.

77. USSBS, Military Analysis Division, Interrogations, 1:3. Yoshida Akihiko, however, insists that the control of the CAP over a carrier formation was usually the responsibility of the flag carrier’s air officer. Yoshida, letter to author, 5 May 1993.

78. Except where otherwise noted, I am indebted for information in this paragraph and the three that follow it to Jonathan Parshall.

79. The two best technical overviews of Japanese antiaircraft defenses are to be found in J. Campbell, Naval Weapons, and Itani et al., “Anti-aircraft Gunnery,” 81–101.

80. David Dickson, unpublished monograph.

81. A case in point was the critically poor air defense provided for the Shōhō at the Battle of the Coral Sea, which cost the Japanese the loss of the carrier. In that portion of the battle when the Shōhō was under air attack, the overall tactical commander, Rear Adm. Gotō Aritomo, deployed his four heavy cruisers 8,000 yards (7,300 meters) from the carrier, which had only a single destroyer as plane guard nearby. H. P. Willmott has written, “It was almost as if the cruisers were trying to disassociate themselves from the carrier in the hope that they might escape attack themselves. They were certainly not in positions to provide the Shōhō with flak support.” Willmott, Barrier, 244.

82. I am indebted to Alan Zimm, USN Ret., for making this point. Zimm, letter to author, 26 May 1993.

83. Dickson, Battle of the Philippine Sea, 129.

84. KKG, 206; Garzke and Dulin, Axis and Neutral Battleships, 113.

85. Interview by David Evans with Yoshida Akihito, 18 October 1989.

86. Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 482–86.

87. Shimada, “Opening Air Offensive,” 72–82.

88. It is true that certain of the navy’s prewar planning documents contain references to an extended war of attrition to be fought behind an impregnable barrier that the navy would supposedly create against an anticipated American counteroffensive in the Pacific. Yet the navy’s technological innovations, its force structure, the decades-long evolution of its tactics, and its specific plans for the Pearl Harbor assault were all obviously developed with the underlying assumption that Japan must achieve immediate and decisive superiority over the enemy. These matters are discussed in greater detail in Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 447–86.

89. Marder, Old Friends, 1:315.

90. KKG, 105, 288, 211.

91. At the opening of hostilities, it appears there were no more than twenty land-based and flying-boat transport aircraft within the Eleventh Air Fleet, the force that spearheaded the Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia. Favorite with Kawamoto, Japanese Air Power.

92. SS: Nantō hōmen kaigun sakusen, 2:642.

93. At the opening of the war, not counting the fuels already distributed to its individual air groups, the navy believed that it had on hand 477,500 tons of aviation gas, 6,470 tons of aviation lubricants, 26,926 tons of iso-octane, and over 61 tons of ethyl fluid. KKG, 109–10.

CHAPTER 7. DESCENDING IN FLAME

1. Among the mountains of literature in English on the Japanese navy’s attack on Oahu, Prange, with Goldstein and Dillon, At Dawn We Slept, continues to be the nearest thing to a definitive history of the operation.

2. The most extensive English-language account of the sinking of the Repulse and Prince of Wales is Middlebrook and Mahoney, Battleship: The Loss of the Prince of Wales and the Repulse. The most authoritative English-language account is Marder, Old Friends, 1:465–90. Unless otherwise noted, the discussion in the following four paragraphs is based on Marder.

3. SS: Hitō-Marē hōmen kaigun shinkō sakusen, 464.

4. The Japanese claimed twenty-one torpedo hits on the two ships, but British records assert that there were only eleven, five on the Repulse and six on the Prince of Wales. Marder, Old Friends, 470.

5. Ibid., 493.

6. Ibid., 482–93.

7. SS: Hitō-Marē hōmen kaigun shinkō sakusen, 491.

8. To date, the best English-language treatment of the Japanese aerial sweep of Southeast Asia from December 1941 through February 1942 is Shores and Cull, with Izawa, Bloody Shambles, vol. 1. A critical look at the nature of the Japanese aerial offensive is provided in Harvey, “Japanese Aviation and the Opening Phase of the War in the Far East,” 174–204.

9. Osamu Tagaya notes that fighter combat practice in the prewar United States Army Air Corps was also essentially dogfighting, and even the United States Navy, though it emphasized a greater degree of deflection shooting than its sister service, largely practiced turning combat. Faced with an enemy flying superior aircraft and using superior tactics for this type of combat, American pilots could not hope to be effective. Tagaya, communication to author, 1 February 2000.

10. U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Intelligence, “Quality of Japanese Naval Pilots,” 3342.

11. Lundstrom, First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat, 188.

12. Ibid., 300–305; Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 92; James Sawruk, letter to author, 7 April 1998.

13. Lundstrom’s First Team: Pacific Naval Air Combat is the most detailed and authoritative English-language source for the tactical aspects of air combat at Midway.

14. Rearden, Cracking the Zero Mystery, details the recovery of a reasonably intact Zero that had crash-landed in the Aleutians in the summer of 1942 and that was subsequently refurbished and flight-tested in the United States. Supposedly this recovery was a tremendous Allied windfall, revealing as it did the critical secrets of the Zero and thus leading to its extermination at the hands of Allied fighter pilots. But John Lundstrom deflates this myth by explaining how American fighter pilots had already analyzed the Zero’s strengths and weaknesses in actual combat against it. Lundstrom argues that it was the loss of good Japanese pilots through attrition, not the loss of technical secrets, that ultimately led to the downfall of the navy’s Zero fighter units. Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 533–36. Other models of the aircraft were captured during the later course of the war and evaluated against Allied aircraft at the naval air stations at Anacostia, Va., and Patuxent River, Md. Mikesh, Zero, 70.

15. Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 92.

16. SS: Midowei kaisen, 598.

17. Prados, Combined Fleet Decoded, 337; James Sawruk, communications to author, 31 March, 1 April, and 7 April 1998. Sawruk has devoted intensive study over the years to the great carrier battles of 1942. In compiling this figure he used, among other sources, Sawachi Hisae’s Midowei kaisen, which provides a wealth of statistical data concerning aircraft and personnel losses on both sides at Midway drawn from published accounts, unpublished Japanese navy reports, shrine records at Yasukuni Jinja, newspapers, records of veterans associations, and personal interviews with survivors and survivors’ families. Sawruk tabulates the Japanese aircrew losses as follows: Akagi, seven (three in the air and four aboard ship); Kaga, twenty-one (eight in the air and thirteen aboard ship); Sōryū, ten (six in the air and four aboard ship); and Hiryū, seventy-two (sixty-four in the air and eight aboard ship). Sawruk, communication to author, 31 March 1998.

18. Prados, Combined Fleet Decoded, 337. The recollections of Genda Minoru and Lt. Comdr. Yoshioka Chūichi, both on the staff of the First Air Fleet during the Midway operation, support these contentions. SS: Midowei kaisen, 598–99.

19. KG, 1:270–72.

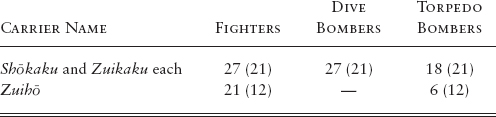

20. Genda, “Tactical Planning,” 48; Friedman, Carrier Air Power, 56.

21. With the establishment of the Third Fleet in July 1942, the standard loading by aircraft type for its three carriers was as follows (prior aircraft complements in parentheses):

Source: SS: Midowei kaisen, 639.

22. Moore, “Shinano,” 147.

23. John Lundstrom’s First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign provides the most authoritative and lavishly detailed English-language source for the study of the air war in the Solomons, though it gives greater attention to the American side of the conflict than to the Japanese. Eric Bergerud’s recently published Fire in the Sky complements, but does not supersede, Lundstrom’s study.

24. Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 41–44.

25. For a discussion of the paucity and backwardness of the navy’s base construction forces, see Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 400–401.

26. KKG, 265–66; KSS, 407; McKearney, “Solomons Naval Campaign,” 60–61; U.S. Department of the Army, Japan Monographs no. 122, 4.

27. Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 173.

28. KKG, 267; Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 190. It is impossible to determine with precision the losses suffered by Japanese naval air units in the Solomons. Perhaps the most thorough analysis of the casualty figures, compiled both from Japanese accounts and records, including the Japanese Defense Agency SS (Senshi sōsho) volumes, and from American records and reports, is to be found in Frank’s Guadalcanal, 761–63. Frank estimates that the navy lost something over nine hundred aircrew in combat from 1 August 1942 to 15 November but admits this figure may be conservative.

29. SS: Nantō hōmen kaigun sakusen, 2:309–12; Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 454. Those few experienced aircrews who survived through the autumn of 1942 were apparently sent home to rest and in most cases became instructors in naval air training units. Their return to combat by the summer of 1943 marked a brief resurgence in the quality of aircrews encountered by Allied pilots. U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Intelligence, “Quality of Japanese Naval Pilots,” 3343–44.

30. Ninety aircraft were lost at the Battle of the Coral Sea (47 from the Shōkaku, 33 from the Zuikaku, 10 from the Shōhō); 110 were lost at Midway (7 from the Akagi, 21 from the Kaga, 10 from the Sōryū, 72 from the Hiryū); 61 were lost at the Battle of the Eastern Solomons (27 from the Shōkaku, 21 from the Zuikaku, 13 from the Ryūjō); and 148 off the Santa Cruz Islands (55 from the Shōkaku, 57 from the Zuikaku, 9 from the Zuihō, 27 from the Jun’yō). At the end of the Pacific War only 20 percent of the original Pearl Harbor participants had survived. James Sawruk, communications to author, 1 and 7 April 1998, 27 January 2000.

31. SS: Nantō hōmen kaigun sakusen, 1:642; Mikesh, Zero, 89; Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 45, 190; KSS, 405–6; McKearney, “Solomons Naval Campaign,” 59–60; Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, 164.

32. Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 45, 57.

33. KSS, 408; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 522–23.

34. Lundstrom, First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 529; Hata and Izawa, Japanese Naval Aces, 132–38.

35. Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, 246–49.

36. KSS, 406; KKG, 266.

37. KSS, 394–98.

38. Ibid., 407–8.

39. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 459–60.

40. Ibid., 478–79.

41. All these elements are analyzed in Lundstrom’s First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, 477–85.

42. From 1942 through 1944 the United States carried out a series of flight evaluations of captured Zeros to compare their performance with that of U.S. fighter aircraft of the time. The results of these tests demonstrated that even though the Zero was inferior in some respects to later Allied fighters, it could never be discounted as a lethal fighting machine. By inference, then, it is probable that the severe losses to which Japanese naval air groups had been subjected by the end of 1942 were more the result of changing balances in the skills of Japanese and American pilots and their use of tactics than to any deficiencies in the Zero. Mikesh, Zero, 83.

43. KKG, 266.

44. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 505–7.

45. U.S. Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Intelligence, “Quality of Japanese Naval Pilots,” 3342.

46. Osamu Tagaya, letter to author, 31 March 1998.

47. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 329.

48. Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 117–18, 125–27; KKG, 310; Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, 191–95; Ugaki, Fading Victory, 328–29.

49. Sakaida, Siege of Rabaul, 6.

50. Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 347.

51. Sakaida, Siege of Rabaul, 6–8, 22, 27–31; Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, 284–93; Dull, Battle History, 293; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 647–48, 653–54.

52. Dickson, Battle of the Philippine Sea, 28–29.

53. SS: Mariana-oki kaisen, 636.

54. Dickson, Battle of the Philippine Sea, 29.

55. Dull, Battle History, 303–4.

56. Ibid., 303–10; Dickson, Battle of the Philippine Sea, 115, 168; quotation from Tillman, Carrier Battle in the Philippine Sea.

57. Morison, New Guinea and the Marianas, 317–18.

58. See Fukui, Japanese Naval Vessels at the End of the War.

59. Mikesh, Broken Wings of the Samurai, 28.

60. Agawa, Reluctant Admiral, 105.

61. By March 1944 the number of navy aviators had nearly doubled to fourteen thousand (as compared with combat deaths of almost four thousand). Most of these were enlisted personnel. KG, 2:202.

62. Fuchida and Okumiya, Midway, 208.

63. These considerations were suggested by Osamu Tagaya in a letter to the author, 31 March 1998.

64. Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 189, 429–32.

65. John B. Lundstrom, letter to author, 6 December 1993. In the Pacific War, picket submarines, occasionally stationed in projected combat areas, as in the Pearl Harbor, Midway, and Guadalcanal operations, were also given sea rescue as part of their mission. However, these arrangements hardly constituted a consistent air-sea rescue system, particularly since there were no direct communications between submarines and aircraft. USNTMJ, Report S-17, “Japanese Submarine Operations,” 12.

66. Okumiya and Horikoshi, with Caidin, Zero!, 172.

67. KKG, 210, 266; Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 141–42.

68. KKG, 209.

69. Ibid., 336, 343.

70. KG, 1:818.

71. KKG, 209–10.

72. Ibid., 341–42; NKKS, 2:634–36. For a more detailed discussion of the navy’s general prewar and wartime fuel problems, see Evans and Peattie, Kaigun, 406–11.

73. KKG, 270.

74. These thoughts are provoked by comments in ibid., 267–70.

75. See, for example, Bergerud, Fire in the Sky, 554–55.

76. Bergerud makes this point in ibid.