Japanese Naval Aircraft and Naval Air Tactics, 1920–1936

During World War I, each of the four future roles of naval aviation had been demonstrated on one or more occasions. These roles were fleet reconnaissance, spotting for naval gunnery, attack (against both maritime and land-based targets), and protection of friendly forces at sea or ashore. Such was the promise of aircraft to project naval power beyond the range of shipborne weapons that each of the world’s major navies felt impelled to develop a naval air arm in one form or another. By the opening of the 1920s, each had included in its roster of warships at least one prototype of aircraft carrier: the Langley for the United States, the Argus and Furious for Britain, and the Hōshō for Japan.

Yet since none of the trials of naval aviation in the recent war had proved decisive, most of the thinking about the future of the new arm lay in the realm of speculation rather than experience. On the basis of recent history there was little evidence to shake the faith of naval establishments in the continued primacy of the big-gun battleship. During the 1920s the battleship-oriented brass in all navies had scant regard for the average aircraft of the day as offensive weapons, though they had already come to appreciate the role that aircraft could play in spotting for naval gunnery.1 Small, fragile, capable of flying only short ranges, without adequate means of communication with ships or shore bases, equipped with only the crudest navigation systems, incapable of delivering their bombs with any accuracy, and subject to grounding in any sort of bad weather, early naval aircraft had few capabilities to suggest that they were a serious threat to surface ships. True, heavy bombers of the United States Army Air Corps had sunk an old German battleship anchored off the Virginia Capes, but the dubious conditions that surrounded this test made its outcome inconclusive. If anything, the circumstances of the experiment seemed to indicate that level bombing by aircraft could not destroy a well-defended battleship.

But the limited offensive power of horizontal bombing reflected the circumscribed capabilities of naval aviation as a whole.2 During much of the period 1920–37, the modest performance of naval aircraft (in speed, range, ceiling, and payload), and thus their modest potential, meant that in all three major navies “command of the air” was seen largely in relation to the decisive surface engagement that would be fought by the big guns of the capital ships of the line far out at sea.3 At the outset of the 1920s, the reconnaissance function of naval aviation had matured with the use of battleship and cruiser floatplanes as scouts for the fleet. In the United States Navy these same aircraft were being used to spot the fall of shot from the battle line, a task that in the Japanese navy began to be shared by carrier aircraft as they appeared in greater numbers. Because of the potential advantage provided by such spotter aircraft to the accuracy of surface firepower, the dominant battleship orthodoxy in both the U.S. and Japanese navies came to emphasize the problem of control of the air space above the battle fleet, or, more exactly, over the decisive battle area. Naval tacticians in Japan and the United States concluded that such control could best be secured by the use of carrier fighter planes to destroy or drive off the enemy’s scouting and observation aircraft. By the beginning of the 1930s this had raised the question of how to prevent the enemy from doing the same. The eventual conclusion in both navies was that control of the air space over the battle area could best be achieved by sinking or crippling the enemy’s carriers at the outset, an imperative identified by the U.S. Naval War College as early as 1921.

That tacticians in the Japanese and American navies viewed carriers, not big-gun capital ships, as the proper targets for naval air power is explained by the fact that at the beginning of the 1930s few naval professionals had much confidence that carrier-borne attack aircraft could actually destroy a capital ship, though there was increasing speculation that such aircraft could at least damage and thus slow down an enemy battle line. There was, however, increasing conviction that such aircraft could destroy or effectively disable aircraft carriers, given the vulnerability of the latter. During the 1930s the development of higher-performance aircraft—marked in particular by significant improvements in radial engine design and manufacture—made it possible for carrier aviation to attack enemy fleet units at several hundred miles’ distance. Moreover, the development of two carrier-borne offensive systems—torpedo bombing and dive bombing—increased the vulnerability of both battleships and carriers (in proportional degree). These developments opened up a debate on the question of which should be the primary objective of carrier strikes: the enemy’s battle line or his carriers. Different answers to this question were posed by the two most interested elements in the Japanese and American navies—big-gun proponents and aviation advocates—though the evolution of such carrier doctrine was somewhat different in each navy. But by the second half of the decade, it was the preemptive strike against the opposing carriers that seemed to promise the key to victory.

Moreover, it was not fully recognized at the time how rapidly a preemptive carrier strike could inflict damage, thus dramatically changing an inferior naval force’s odds of defeating a numerically superior enemy. In this regard, the carrier age largely overturned the N2 Law and the calculations of F. W. Lanchester. In 1914 this distinguished British engineer had demonstrated in algebraic form that in modern naval combat, gunnery conferred an expanding cumulative advantage on the side with the numerical preponderance of firepower. But now, not being the target of continuous fire by an enemy battle line, a numerically inferior fleet of carriers could, if it launched a preemptive aerial strike against a numerically superior foe, summon up the equivalent of a single enormous salvo, one that could destroy the enemy in one great “pulse” of firepower.4 But the great carrier battles of the Pacific War that would demonstrate this new equation of firepower lay in the future. In the intervening decades, those responsible for aircraft design and manufacture struggled with problems of drag, weight, performance, firepower, and the rest of the challenges to aviation engineering that lay between them and the development of aircraft that could dominate combat in oceanic skies.

JAPANESE NAVAL AIR TECHNOLOGY

Aircraft Design and Manufacture

The Sempill Mission had not been the only source of foreign air technology in the postwar decade, nor was the navy the sole beneficiary. Until this time, Japanese naval aviation had been mostly dependent on the purchase of foreign-manufactured engines and airframes, or on their manufacture in Japan under foreign licensing arrangements. But at the beginning of the 1920s, Western technological assistance began to provide the basis for the development of an independent Japanese aircraft industry.5 The first naval aircraft manufacturer in Japan was the Naval Arsenal at Yokosuka (Yokosuka Kaigun Kōshō, or Yokoshō for short). As early as 1914 the Yokoshō had turned out small numbers of seaplanes, the design for which had been based on foreign airframes.6 In 1920, to escape the cramped facilities at Yokosuka, the navy had established another production center at Hirō, just east of Kure, as a branch of the Kure Naval Arsenal. It was to the Hirō Branch Arsenal (known by the acronym Hirōshō) that the navy invited a small group of engineers from the Short Brothers, the British firm noted for its manufacture of large flying boats. With this assistance the navy began what was to be a quarter century of production of outstanding aircraft of this type.7 In 1923 the Hirō Branch Arsenal was upgraded to the Hirō Naval Arsenal, but it retained an aircraft department. In 1932 it was phased out as a center for aircraft development, and its technology was transferred to the Mitsubishi Aircraft Corporation. Thereafter the function of the Hirō Arsenal and its two branches at Ōita and Maizuru was to augment the production of aircraft and aircraft engines already developed by commercial manufacturers.

In their scramble for participation in an increasingly lucrative business, private firms in Japan were not far behind in the design and manufacture of aircraft. Established commercial and industrial firms began to build research and testing facilities, including wind tunnels and water tanks to study lift and drag. To master the new developments in aeronautical science in the West, they hired foreign technicians, sent their engineers abroad, and purchased foreign aircraft for intensive study and analysis. Mitsubishi had entered the new industry in May 1916 with the establishment of an aircraft fuselage facility in Nagoya, and two years later the company strengthened its participation with the production of fuselage and engine components at its facilities in Kobe. In 1923 the Mitsubishi Internal Combustion Engine Manufacturing Company was established at Ōemachi in Nagoya, the name being changed in 1928 to the Mitsubishi Aircraft Company. Mitsubishi was fortunate at the very outset of its aircraft venture, since it quickly secured a navy contract for the design, development, and production of three different types of aircraft for use with the carrier Hōshō, then nearing completion. It also obtained the services of a British design team headed by Herbert Smith, a talented former employee of Sopwith. Along with the ill-fated test pilot Frederick J. Rutland, Mitsubishi retained another former Sopwith employee, William Jordan, as a test pilot and designer. It was Jordan who made the first landing on a Japanese carrier deck when he touched down on the Hōshō in February 1923 in a Mitsubishi aircraft.

There were three variants of aircraft developed by the British employees of Mitsubishi. Two, the Mitsubishi 1MF (Type 10) carrier fighter,• the first fighter aircraft designed specifically for carrier operations, and the Mitsubishi 2MR (Type 10) reconnaissance aircraft,• based on the general design of the 1MF fighter, proved quite successful. Both remained standard aircraft in the navy until the end of the decade.8 The third, the Mitsubishi 1MT1N (Type 10) carrier attack aircraft, the only triplane ever accepted by the navy, was not a successful design and lasted little more than a year before being replaced.

Another aircraft manufacturer, the Aichi Watch and Electric Machinery Company, established in 1920, began the production of water-based aircraft for the navy at its Nagoya plant that same year. Most of its aircraft were, like those of other manufacturers, of foreign design and produced under licensing arrangements with a foreign firm. Aichi made arrangements with the Heinkel Company in Germany, which eventually dispatched two members of the company to Japan, including the president, Dr. Ernst Heinkel. As a result, Heinkel provided technical assistance in the design of a new generation of naval aircraft.9

Nakajima was the oldest and in some ways the most unusual private aircraft-manufacturing firm in Japan. It was founded in 1917 as the Hikōki Kenkyūshō by Nakajima Chikuhei, the former naval officer and pioneer pilot who eventually became a formidably influential industrialist and politician. Because of his expanding need for capital, in 1918 Nakajima joined with Kawanishi Seibei, a manufacturer of woolen goods, to found the Japan Aircraft Works. The arrangement was soon dissolved after a business dispute, and Nakajima readopted the name Nakajima Aircraft Manufacturing Works (Nakajima Hikōki Seisakusho). While it initially built aircraft and engines from existing designs or through purchase of licensing arrangements for foreign designs, Nakajima was unlike other aircraft- manufacturing firms in that from the beginning it used mainly its own engineers and designers rather than hiring foreign experts. The firm became enormously successful during the 1920s, when it produced a range of first-rate aircraft types for both the Japanese army and navy. One outstanding aircraft that the company sold to the navy was the Navy Type 3 carrier fighter (Nakajima A1N1,• a modified version of the British Gloster Gambet), which replaced the aging Navy Type 10 (Mitsubishi 1MF). Its successor was the Navy Type 90 carrier fighter (Nakajima A2N1).• Based on several American and British designs, it was the first Japanese-designed carrier fighter that “could meet on equal terms the rest of the world’s best fighters.”10 The firm also excelled in the design and manufacture of aircraft engines after the establishment, in 1925, of a plant at Ogikubo, a western suburb of Tokyo, for that purpose.11

Whereas Nakajima manufactured aircraft for both of Japan’s armed services, Kawanishi became essentially identified with the navy, in large part because so many of its staff were former naval officers. After the dissolution of his partnership with Nakajima, Kawanishi Seibei tried his hand at machine-tool manufacturing and then at the production of airplanes for civil aviation for a number of years before turning to the design and construction of naval aircraft. The Kawanishi Aircraft Company was established in 1928, and that same year the firm, in cooperation with the Short Brothers, began work on the first of a number of highly successful flying-boat designs that it undertook on contract with the navy. Thereafter, the Kawanishi name was linked to some of the largest flying boats in the Pacific.12

While Yokosuka remained the center for the direction of aviation technology through the end of the Pacific War, in the early 1920s the navy moved toward a division of labor in the matter of aircraft production. In 1921 the Navy Technical Department was given the authority to issue competitions for the design of aircraft according to certain specifications provided by the Navy General Staff. Private firms like Mitsubishi, Aichi, Nakajima, and Kawanishi would submit the designs, and after the navy tested prototypes, it would award contracts to those firms coming closest to its requirements. It was under these arrangements that, beginning in 1928, a series of competitions produced some of the world’s best reconnaissance aircraft, carrier bombers, and carrier fighters of the 1930s. For its part, the navy, while continuing the design and manufacture of a small number of aircraft types in which it believed that it should take the lead, came to restrict its limited facilities to the testing and modification of aircraft prototypes. Thus, under the new arrangements the navy was to do much of the research, and private enterprise was to undertake most of the production.13

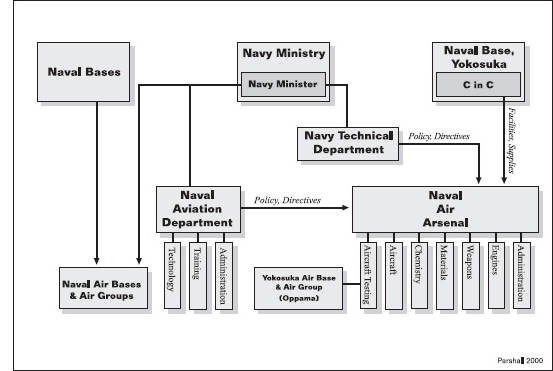

Fig. 2-1. Administrative organization of Japanese naval aviation, 1930s

The development of aviation technology in the Japanese navy was so closely related to the administrative control of naval aviation that I must pause here to say something about the latter. During the early years of naval aviation, its administration was in the hands of the Naval Affairs Bureau of the Navy Ministry, its training was the responsibility of the Naval Education Department, and its technological development was directed by the Navy Technical Department. But with the increase in the scale and complexity of naval aviation, the need for a single administrative organization coordinating these various functions became obvious. For this reason, in 1927 the navy had created the Naval Aviation Department,14 located in Tokyo, directly responsible to the navy minister but remaining outside the Navy Ministry itself. (Fig. 2-1.) In addition to having responsibility for the development of airframes, engines, ordnance, and equipment relating to naval aviation, the department was given charge of all air training, except for air combat training, which remained in the hands of the various air groups.15

Technical research relating to naval aviation took a different route before it too was subsumed under the Naval Aviation Department. In April 1923, in order to consolidate all its research, for both warships and aircraft, the Navy Technical Department founded the Navy Technical Research Institute in Tokyo. This facility was, however, destroyed in the great earthquake of that year, and a new aviation research facility was established at Kasumigaura in 1924. To the Kasumigaura Branch of the Navy Technical Institute the navy brought most of its aeronautical research and testing equipment, though a number of draftsmen and engineers were left at the Hirō facility. In 1929, however, an aircraft-testing station was also established at the Yokosuka Naval Dockyard, which in 1930 also became a testing center for aircraft engines.16

By the London Naval Treaty of 1930, Japan had, with great reluctance and consequent turmoil within its navy’s high command, accepted further limitations on its warship construction in relation to that of the British and American navies, most critically in the cruiser category.17 Now, shorn of its strength in cruisers, which had up to the London Treaty made up for its inferiority in capital ships, the Japanese navy turned to air power to make up for these deficiencies. In view of the increasing potential of air power, at the outset of the 1930s the navy attempted to consolidate its aviation research still further by bringing its technical research facilities together with the tactical training facilities already in existence at Yokosuka. In 1932, construction was begun on a Naval Air Arsenal (Kaigun Kōkūshō, or Kūshō for short), which was completed in 1936 and placed under the command of the Yokosuka Naval Base. The creation of the arsenal brought together for the first time all work in aircraft design and flight testing, as well as the construction of prototypes not under contract with private firms. Though it thus became a center of Japanese naval aviation technology, the arsenal served several masters. While administratively it came under the authority of the Yokosuka Naval Base, for purposes of technological development its management was divided between the Naval Aviation Department and the Navy Technical Department, the former assuming all responsibility for aircraft design and production, the latter having charge of the development and testing of most weapons (except for aerial bombs) and all equipment (cameras, radios, etc.).18 Within the arsenal was the Flight Testing Department (Hikō Jikkenbu), which carried out flight tests of new prototypes as well as of new models of aircraft already in service. It measured their performance under standard conditions to make sure that they were safe and met the navy’s basic performance requirements. If they did, they were passed on to the tactical and training unit, the Yokosuka Air Group (see below), which tested their combat capabilities and suitability for carrier operations. Considering the importance of the large number of aircraft designs that it came to evaluate and the outstanding success of some of these designs by 1937, the establishment of the Naval Air Arsenal as an advanced aviation engineering center marked a giant step forward for Japan as one of the world’s leading aircraft producers.19

In 1932, as its first order of business, the Naval Air Arsenal improved the system of managed competition for the design and development of naval aircraft that had been in use since the 1920s by the Japanese aircraft industry. The new arrangement, known as the Prototypes System, called for the pairing of firms to compete for orders of various types of aircraft that were to be designed and produced according to specifications set forth by the navy. The firm whose prototype successfully met these specifications was awarded the navy contract to put its design into production. But it was far from being a winner-take-all arrangement; the losing firm would be expected to produce its competitor’s design, or to produce the engines for the aircraft, as a second-source supplier. This was a significant innovation, one that coaxed the best competitive energies from private industry in order to obtain the best designs for the navy, but that also led, once the best design was selected, to the synthesizing and sharing of the technologies involved. The Prototypes System was a revolutionary step in the way the aircraft industry came to compete, integrate components, and build aircraft. Not only did it provide the guidelines for a series of outstanding naval aircraft, the first wholly designed by Japanese aircraft engineers; it also laid the basis for the military procurement system that exists in Japan to this day. It was a very Japanese approach to procurement in that it did not drive out the losers in design competition. Rather, it served as a recognizable example of Japanese industrial policy from that day to this, one that provided a series of safety nets to protect strategic industries.20

These organizational details are important to understanding the direction given to the sudden acceleration in Japanese naval aviation technology that took place in the 1930s. Throughout the previous decade, as we have seen, Japanese aircraft production had been based for the most part on foreign designs manufactured in Japan under licensing agreements. Beginning in 1932, with a decade of apprenticeship and experience in aircraft production behind it, the navy moved decisively to become self-sufficient in aircraft design and manufacture. The establishment of the Naval Air Arsenal had much to do with this, but the driving force behind this new policy came out of the Naval Aviation Department itself. There, in 1932, Rear Adm. Yamamoto Isoroku,† chief of the Technical Bureau of the Department from 1930 through 1933 and chief of the department itself, 1935–36, pushed through a plan intended to break the dependence of the navy—and by extension, of the Japanese aircraft industry—on foreign aircraft designs. The plan provided for autonomous production of naval aircraft based essentially on Japanese designs, on the navy’s emerging operational needs, and on the mobilization of civilian aircraft companies.

Like most other air power nations, Japan did not, of course, achieve complete independence from foreign aircraft technology. During the rest of the 1930s the Japanese aircraft industry imported various equipment, engines, and even aircraft, largely from the United States, and during the Pacific War it received at least a trickle of such materiel from its Axis allies.21 Yet Yamamoto’s initiative at the Naval Aviation Department, combined with the Naval Air Arsenal’s Prototypes System, started a process that was to result in the design, development, and production of some of the finest aircraft in the world.

While the Naval Aviation Department was the source of a good deal of innovative thinking about naval air doctrine and technology, effective aircraft design and production was continually hampered by one of the inherent and critical flaws in the prewar Japanese government: the debilitating and corrosive rivalry between the armed services. The ongoing failure of the army and navy to cooperate, as well as the inadequate organizational integration of the navy itself, eventually led to serious aircraft production problems that could have been avoided had there been more opportunities for inter- and intraservice discussion of critical technological issues. This lack of cooperation also led to a prodigious waste of time and technological resources and, by the end of the Pacific war, produced far too many types of aircraft, a situation that limited the overall number of planes that could be produced.22

LAND-BASED AIR POWER

The Naval Air Groups

Even after the Japanese navy had assembled a significant carrier force in the 1930s, it continued to increase its land-based contingents in keeping with its initial strategy of providing a rapid defense of the home islands against the possible westward advance of an American naval offensive. Indeed, it was land-based aircraft that provided the bulk of Japan’s naval aviation up to the eve of the Pacific War. In this the Japanese navy was unique among the three major naval powers during the interwar period. In the immediate prewar years the only analogy to Japan’s shore-based naval air units were the United States Navy’s shore-based patrol squadrons and the two air wings of the United States Marine Corps.

As explained in chapter 1, the creation of land-based naval air contingents had begun in 1916 with the establishment of the Yokosuka Naval Air Group, followed after the end of World War I by the establishment of air groups at Sasebo, Kasumigaura, and Ōmura. Given the navy’s concentration on the surface navy, particularly its cruiser force, no similar units were established for the remainder of the 1920s, nor did any comprehensive administrative system exist for land-based naval air power. Then, beginning in 1930, confronted with the restrictions on surface ship construction to which Japan had agreed at the London Naval Conference that year, the navy determined to make up for these restrictions by strengthening its naval air arm. Between 1930 and 1937, under the first two of the navy’s “Circle” programs (its shorthand designation for a series of interwar naval expansion programs),23 air groups were established at nine new air bases around the Japanese home islands and in Korea: Tateyama, Kure, Ōminato, Saeki, Maizuru, Kisarazu, Kanoya, Yokohama, and Chinkai (Chinhae). (Map 2-1.)

By the end of 1937 the navy possessed 563 aircraft based ashore. Added to the 332 aircraft aboard its carrier fleet, it thus had a total of 895 aircraft and 2,711 aircrew (pilots and navigators) in thirty-nine air groups.24 While Japan’s carrier aircraft were considerably fewer in number than the total American naval air strength for the same period, its shore-based naval aircraft were substantially more numerous. This discrepancy in force structure would have been meaningless at the outset of any encounter between the two naval powers in the 1930s. But Japan’s substantial land-based air power was to work to its advantage when it went to war in 1937 with a land power, China.

Map 2-1. Japanese naval air bases, home islands, 1916–1937

JAPANESE NAVAL AIR RECRUITMENT AND TRAINING

While production of the aircraft for the new land-based air groups, as well as for the increasing number of carrier-based air groups, strained Japan’s aircraft production facilities at the time, the greatest problem was to provide the necessary increase in air and ground crews. This task was made more difficult by the competing demands of the army, as well as by the navy itself, since the navy required that its fleet carriers and floatplane-carrying battleships and cruisers maintain their full complements of aviation personnel.25 From the earliest days of the Yokosuka Air Group’s establishment, Japanese naval aviation, unlike the other branches of the service, mainly used its operational units as training facilities rather than training its personnel in specialized schools. The advantage of this system was that it gave aviation training more flexibility in dealing with the navy’s budgetary fluctuations. For example, if it was determined that naval air training should be suddenly expanded, as happened at the outset of the 1930s, it was possible to shift resources (both personnel and equipment) from regular operational units in order to do so.26 Eventually, in 1930, the Kasumigaura Air Group was designated as the unit for basic flight training for student pilots and aircraft maintenance for student mechanics, while the Yokosuka Air Group was once more designated as a training unit, now specializing in advanced flight training in aerial combat and air reconnaissance. The Yokosuka Air Group was also used, as I shall explain, in the flight-testing of experimental aircraft.

Improved training was predicated, of course, upon an adequate supply of intelligent, healthy, and motivated young recruits. At the beginning, it had been planned that only Naval Academy graduates would become pilots. But it was soon realized that this trainee pool would have to be expanded. Thus, regular training of noncommissioned officer pilots began in 1916, and by about 1921 the number of noncommissioned pilot trainees was already higher than that of officer pilot trainees, and thereafter so remained.27 Moreover, with the anticipated growth in the number of air groups early in the 1930s, the number of academy graduates volunteering for the naval air service was obviously inadequate, and the lengthy preparation they had received for service in the surface fleet was largely irrelevant to achievement of proficiency in naval aviation.

Two parallel training programs were therefore established that radically expanded the pool of pilot trainees in the naval air service. The first of these, created in 1928, was a program for noncommissioned officers, designated in 1930 as the Pilot Trainee System (Sōjū Renshūsei, or Sōren for short). This program recruited and trained noncommissioned officers drawn from fleet service. The second, established in 1929, was the Flight Reserve Enlisted Trainee System (Hikō Yoka Renshūsei, or Yokaren for short), which drew its candidates directly from civilian life. It provided for the recruitment and training of boys fifteen to seventeen years of age who had finished primary school, who were in excellent physical condition, and who were at the top of their classes. Inducted into the navy, these youngsters were given three years of general education—similar in part to the training at the Naval Academy—that brought them beyond the middle-school level, after which they would be given a short period of training at sea. Then, depending upon their abilities, they would be divided into pilot and observer candidates and given specialized training at one of the air groups. While a small number of trainees still continued to be drawn from commissioned volunteers, the great majority of Japanese naval air pilots and observers up through the Pacific War were produced through either the Sōren or the Yokaren system, an arrangement that made Japanese naval air training markedly different from that in the United States Navy, which largely restricted pilot training to those of commissioned rank.28

Beginning in 1934, flight training was also available to a small number of college and university graduates who had majored in oceanography and who were members of the Japanese Student Aviation League. After their admission into the Student Aviation Reserve (Kōkū Yobi Gakusei) program, these students were given about two months of general naval education followed by ten months of pilot training at Kasumigaura. Graduates of this program become reserve ensigns. The first three classes (up to March 1937) specialized in carrier attack aircraft and seaplanes, while later classes were trained in various types of aircraft. After Pearl Harbor this program expanded rapidly, training over ten thousand men in 1943.29

While undertaking a complete overhaul of its recruitment system for pilots and observers, the navy took steps to make its flight training both more uniform and more rigorous. Although the Sempill Mission had considerably improved Japanese naval air training in general, for the rest of the 1920s training focused largely on simply improving flying skills, specifically carrier-deck takeoffs and landings. To a certain extent the flight instruction provided by the Sempill Mission had left an inhibiting legacy, in that it had tended to encourage the intuitive abilities of a handful of star pilots while failing to put in place an adequate program of routine practice to improve the skills of the average pilot trainee. One officer who had felt this most keenly was Capt. Yamamoto Isoroku, who had arrived at the Kasumigaura Air Group in September 1924. Several months later he became the group’s executive officer, the first assignment in what was to be a close identification with naval air power for the rest of his life. While at Kasumigaura, he underwent flight training and soloed, an unusual initiative in the navy at this time for someone of his rank. Convinced that the navy’s single aircraft carrier was useless if only a few skilled pilots were able to land on it, Yamamoto soon cracked down on what he saw as the careless, daredevil elitism of the best of Japan’s prospective naval aviators and came to insist on relentless and rigorous drill for the broad mass of trainees at Kasumigaura. Later on, he instituted intensive training in instrument flying of the sort that Lindbergh and Admiral Byrd had pioneered so successfully.30

Yamamoto left Kasumigaura at the end of 1925 when he was assigned to Washington, D.C., as naval attaché. But the rigorous training he had insisted upon continued, much of it devoted to carrier takeoffs and landings, practiced both on land and on the deck of the Hōshō. With the addition of the Akagi to the fleet in 1928, the navy formed the First Carrier Division, which made it possible for aircrews to gain experience in flight operations involving more than one carrier. Thus, while takeoffs and landings still occupied much of the training of carrier pilots, an increasing amount of time was given over to tactical training once the ships of the First Carrier Division began to maneuver together.

Photo. 2-1. Yamamoto Isoroku (1884–1943) in the rank of captain

EMERGENCE OF AIR ATTACK TECHNIQUES

By the 1930s, Japanese naval air doctrine had begun to shift away from an emphasis on aerial scouting and reconnaissance toward the idea of using aircraft to attack enemy fleet units. Consequently, for much of that decade greater attention was given to the development of effective tactics and aircraft for attack missions than to the development of tactics and aircraft for defensive interception of enemy planes. Indeed, the initial combat operations of the naval air service two decades before had been offensive rather than defensive. The navy’s first attempt at aerial bombardment against enemy surface units had been the horizontal bombing attack carried out at Tsingtao in the autumn of 1914, an operation undertaken with crude bombsights and almost no training, and thus without any significant results. After the war the Sempill Mission had provided some instruction in horizontal bombing (sui-hei bakugeki), along with some British bombsight technology.

But Japanese interest in this particular tactic had largely been aroused by the publicity surrounding the bombing tests off the Virginia Capes in 1921. The storm of controversy provoked in America by these tests was reported in some detail to the Japanese naval high command by Comdr. Yamamoto Isoroku, then on detached duty for study in the United States.31 While the conditions for the tests—the bombardment of anchored, unmanned, and undefended vessels—had been controversial and the results inconclusive, air enthusiasts in both Japanese services had insisted in carrying out similar experiments in their own country. The target selected was the undefended, unmanned, and drifting hulk of the coast defense ship Iwami (the former Russian battleship Orel) off Yokosuka in July 1924. While bombs dropped from an average height of 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) eventually sent the Iwami to the bottom, critics noted that it took nearly four hours to do so, that no more than 20 percent of the bombs hit the target (a ratio that nevertheless compared favorably with the American tests), and that it left unresolved the question of how such an attack would have fared against modern battleships under way and defended both by their own antiaircraft guns and by fighter aircraft. Predictably, battleship and air power proponents in the navy argued over the results of this sort of bombing test in the same way that their counterparts disagreed in the United States.32

During the remainder of the decade, the navy annually carried out further experiments in horizontal bombing to improve bombing equipment, aiming skills, and bomb release techniques. Practice runs were made at medium heights of between 2,000 and 5,000 meters (7,000 and 16,000 feet), either by single aircraft or by small formations of two or three planes aiming on stationary targets. While the results of these tests were reasonably good, the attempt after 1930 to make the tests more realistic by directing them toward moving targets caused hit percentages to plummet. To make them more effective, bombing runs were lowered to 1,000 and even 100 meters (3,000 and 300 feet), at speeds of not more than 50 knots. Accuracy improved somewhat, though it was recognized that in actual combat, bombing at such low altitudes and speeds would make the attacking aircraft extremely vulnerable to defensive fire. Thus, in the mid-1930s the navy tried an alternative technique: a return to higher bombing runs, now carried out by larger formations of bombing aircraft whose ordnance would create a larger bomb pattern to assure that at least some would score hits on a moving target. But while both techniques improved hit ratios somewhat, the ongoing problems in horizontal bombing were the lack of an accurate bombsight and inadequate training to improve coordination between bomber pilots and bombardiers. Thus, the results achieved were still so unsatisfactory and the probable risks in actual wartime situations so great that voices began to call for a halt to level bombing altogether. It was not until a year before the Pacific War that special team training, initiated to improve coordination between bomber pilots and bombardiers, began to increase substantially the accuracy of bombing runs against stationary targets. Against moving targets, little progress was made, and in consequence the navy developed two other bombing tactics that promised greater and more consistent success: aerial torpedo attacks and dive bombing.33

Of these two tactical alternatives, aerial torpedo bombing was the first studied by the naval air arm. The tactic appealed to the Japanese navy because it was technologically feasible; because it was tactically related to surface torpedo warfare; and because it was in keeping with the navy’s offensive tradition. Japanese naval interest in aerial torpedo operations had emerged as early as 1912, at the birth of Japanese naval aviation itself. Considerable impetus to the idea had been provided by a series of simulated night attacks, launched by aircraft based at Oppama on Japanese fleet units at Tateyama Bay in Chiba Prefecture during the naval maneuvers of 1916. During these years, moreover, a number of the navy’s early aviators had begun to argue the importance of developing what they saw as the enormous potential of the new tactic. Among these were lieutenants Nakajima, Kaneko Yōzō, and Kawazoe Takuo. In 1919, Kawazoe drafted a pioneer study, “On Torpedo Attacks” (Raigeki-ron), which is said to have made a powerful impression on his fellow aviation pioneers.34

The principal obstacle to the more rapid advancement of this tactical concept during these years was a lag in the development of the required technology—of the torpedoes themselves, of the aircraft to carry them, and of the mechanisms to assure their steady flight first through the air and then through the water. In particular, the navy possessed no torpedoes sufficiently small to be carried by the lightweight aircraft of the day but sufficiently rugged to withstand the impact of being dropped from any great height above the water, since the impact forces tended to break, bend, or otherwise mutilate the torpedo. The demonstration of aerial torpedo attacks provided to navy pilots by the Sempill Mission at Kasumigaura had used only wooden dummy torpedoes. When real torpedoes were first used in an exercise in Tokyo Bay in 1922, the devices had to be dropped at a height no greater than 5 or 6 feet (1.5 or 2 meters) above the water and at an airspeed of no more than 50 knots in order to assure a successful run against a target. In combat, of course, these limitations would have left attacking aircraft extremely vulnerable to enemy antiaircraft fire and even, in a rough sea, at hazard from the waves.35

Over time, these difficulties were surmounted by research along a number of different lines. In 1931, largely through the work of Ordnance Lt. Naruse Seiji,† who had studied the relevant technology in Britain and who had successfully designed and tested an experimental model, the navy adopted the Type 91 aerial torpedo. The Type 91 was a formidable weapon. It had a range of 2,000 meters (7,000 feet), a speed of 42 knots, and an explosive charge of 150 kilograms (331 pounds).36 It could be launched at an airspeed of 100 knots and heights of 100 meters (300 feet). In these respects it was slightly inferior to the later American torpedo, the Mark XIII, employed at the start of the Pacific War. The Japanese navy’s preference was for greater hit probability at short ranges—which necessitated lower release speeds—and the navy gave only secondary consideration to the vulnerability of the aircraft carrying the torpedo. While the Type 91, like all aerial torpedoes, contained a significantly smaller explosive charge than a torpedo fired from surface craft, the Japanese navy was certain that hits by four or five of them would doom a battleship.37 The Type 91 went through many versions that increased its strength, launch speeds, and explosive power, but it remained the standard aerial torpedo of the Japanese navy from its development to the end of the Pacific War, and its most famous victims were the British capital ships Repulse and Prince of Wales at the outset of the war.

The problem of impact forces breaking or deforming the torpedo shell was solved by strengthening the body structure. The first efforts involved constructing a thicker hull; subsequently T-bars (and, later, I-bars) inside the hull were added. Later versions of the Type 91 were strong enough that they could survive water entry with launch speeds up to 350 knots.38 But air-launched torpedoes must have satisfactory aerodynamic characteristics prior to water entry and satisfactory hydrodynamic characteristics after water entry. Resolving the conflicts between these requirements took many years. The problems of entry angle, pitch, yaw, and especially in-flight roll of the torpedo—which affected the course of the torpedo once it entered the water—tested the ingenuity of the engineers at the Naval Air Arsenal. Some of these problems were not completely solved until the eve of the Pacific War. In 1930 the development of a metal coil-spring release mechanism in the aircraft carrying the torpedo helped assure that the torpedo would assume the required angle upon impact with the water. During the 1930s the technical staff recognized that the problems of pitch and yaw during air flight could be reduced by extensions to the fins affixed to the tail assembly of the torpedo. It took more time, however, to solve the combined problem of designing an aerial torpedo with both the aerodynamic characteristics required for launching from any significant height and the hydrodynamic characteristics necessary for the weapon to follow a predetermined course and depth once it entered the water.39

The aircraft employed to carry the new torpedo was also the result of many years of development. In 1923 the British aircraft designer Herbert Smith, employed by Mitsubishi, designed an all-around carrier-based attack aircraft to replace the triplane Type 10 (Mitsubishi 1MT1N), whose configuration had proved impractical. After years of testing and several preliminary models, his design was finally adopted by the navy in 1931—an unprecedented lag between design and adoption—as the Type 13-3 carrier attack aircraft (Mitsubishi B1M3),• a single-engine three-seater aircraft that could carry one 45-centimeter (18-inch) torpedo or two 250-kilogram (551-pound) bombs.40 The next year the Type 13-3 was embarked on the carriers Hōshō and Kaga and served as the navy’s main attack aircraft during the brief aerial combat over Shanghai in 1932.

Along with these advances, there had emerged, as early as the mid-1920s, a coterie of dedicated, skilled torpedo pilots like Lt. Comdr. Kuwabara Torao and lieutenants Kikuchi Tomozō,† Maeda Kōsei,† and Saitō Masahisa† who, through constant practice in day and night attack methods, came to develop aerial torpedo tactics into a powerful offensive system.41 It is a mark of their capabilities that Kuwabara and Kikuchi were among the handful of naval airmen who came to hold carrier commands in the Japanese navy.

Given the lag in technology and organization, tactical doctrine came slowly, and until 1928 most aerial torpedo practice was carried out by single aircraft. The same lag also allowed the early development of certain tactical concepts that now seem bizarre. One example stemmed from the navy’s concern that in the decisive fleet encounter, enemy capital ships would be able to avoid torpedoes launched from Japanese surface destroyer (torpedo) squadrons by turning away. Convinced that only torpedo planes could thwart this maneuver, the navy attempted to work out a scheme for the coordination of surface and air attacks, with torpedo aircraft in a supporting role. In April 1928 the formation of the First Carrier Division, bringing together a number of ships and aircraft, permitted the navy to attempt such a tactical scheme. In annual maneuvers held that summer off Amami Ōshima, the First Fleet, which included the First Carrier Division’s Hōshō, practiced coordination between the Hōshō’s air attack squadron, the fleet’s cruiser squadrons, and its surface destroyer flotillas. Because the aircraft and aerial torpedo technology of the day required a low-level, low-speed attack, the tactic called for the torpedo aircraft to orbit on station while waiting for the surface torpedo forces to get into position and then, after the latter had done so, to attack the enemy from the unengaged side.42 (Fig. 2-2.) By middecade, Japanese torpedo aircrews themselves had become skeptical about the feasibility of such a tactical scheme in actual combat, and commentators today are even less charitable about the idea. A tactical situation suitable to an aerial torpedo attack might take hours to develop, while the window of opportunity for such an attack might be of only a few minutes’ duration. It would be quite impractical to launch torpedo aircraft, to have them orbit on station while waiting for destroyers and cruisers to get into position, and, finally, to have the torpedo bombers get into position themselves, all at a time when air-to-air and ship-to-air communications were inadequate. It says volumes about the absence of naval air combat experience and the relative novelty of the use of aircraft at sea, as well as the lag in technology, that this utterly impractical tactic could have persisted as accepted doctrine in the Japanese navy until the mid-1930s.43

In any event, the use of aerial attacks by massed aircraft of different types as a potent offensive element lay further on in the decade, when faster and more powerful aircraft would be launched from larger and more numerous carriers. But with the technological advances in torpedoes, not only were speeds and launch heights in torpedo attacks increased, but the likelihood of hits against moving targets jumped to 60 percent in 1932 and 88.4 percent in 1933. By about 1935, the navy’s torpedo units were regularly scoring hits at a rate of 50 percent under the worst daylight conditions and often 100 percent under the best, so that the navy came to expect an average hit rate of 70–80 percent. Much depended on the weather, of course, and upon the effectiveness of the evasive tactics employed by the target vessels. One reason for the remarkable success in these practice runs was the weakness of naval antiaircraft fire in these years, which meant that few attacking aircraft were judged to have been downed. Nevertheless, when one considers that the calculations necessary in aerial torpedo bombing—the target’s course, speed, and anticipated evasive action; the angle between the torpedo and target; the safe release distance (that between the torpedo’s point of entry into the water and the point at which its detonator activated); and the distance at which the aircraft had sufficiently closed the target (not more than 1,000 meters [3,000 feet])—all had to be made with the naked eye, the high hit rates achieved by Japanese naval aircrews during these years demonstrated their great skill and spirit. Year by year, word began to spread throughout the navy that carrier-based air power posed an ominous threat to the main surface forces.44

Fig. 2-2. Coordinated exercise in offensive air tactics, Amami Ōshima, 1928

The last aerial offensive tactic employed by the navy was a technique only recently developed in the West. Dive bombing had been pioneered by the United States Navy in the mid-1920s, in part because of the difficulties and limitations that had been found to hinder both high-level horizontal and low-level torpedo bombing of warships—particularly small, fast warships—under way. In 1926 a fighter squadron at the naval air station at San Diego had experimented with the idea of “glide bombing.” Diving down at land targets in relatively shallow dives and pulling out at about 1,500–1,000 feet (450–300 meters) to release their ordnance, these aircraft had come within a few feet of the target.45 But the tactic of dive-bombing as it came to be developed as a punishingly effective tactic by the United States Navy was born in October 1926 when a flight of navy fighters, diving almost vertically from 12,000 feet (3,500 meters), carried out a simulated and surprise attack on capital ships sortieing from San Pedro Harbor, San Diego.46 Over the next five or six years, various tests and experiments conducted by the United States Navy demonstrated that dive bombing at angles of 70 degrees or more could achieve remarkable accuracy even against smaller, faster warships. The advantage of a near-vertical dive was that the horizontal motion of the dive-bombing aircraft was practically negligible, obviating the need for the pilot to adjust his aim for forward motion; all he had to do was to maintain his sight on the target as it moved. Moreover, these tests showed that because of the height at which the aircraft approached their target, the angle of their dive, and their speed in the dive, the tactic made effective response of shipboard antiaircraft defenses very difficult, and nearly impossible if the dive-bombing aircraft approached on different bearings.47 By the beginning of the 1930s, the main residual problem in the development of dive bombing as a dominating aerial tactic was that there were as yet no suitable dive-bombing aircraft, fighters being too lightweight and structurally inadequate to carry ordnance sufficiently heavy to do real damage to a major warship.

In both the Japanese and American navies the adoption of dive bombing as a major offensive tactic was reflective of a sea change in doctrinal thinking about the role of naval aviation, particularly carrier aviation. The early 1920s had seen carrier aircraft used largely for scouting purposes or for spotting the fall of shell from the battle line. By the end of the decade, the need to control the air above the great gun duel between opposing lines of capital ships—that is, to drive off enemy scouting or spotting aircraft from above the decisive battle area—had become the primary role for carrier aviation and thus had given rise to the carrier fighter, which was seen as playing a defensive role.48 However, by the beginning of the 1930s, carrier aircraft had come to be viewed as instrumental in attacking capital ships themselves, less in terms of sinking them—since few in either navy saw that as a realistic possibility, given the small bomb loads aircraft of the time were able to carry—than in terms of slowing them down.

Then, in the mid-1930s, Japanese and American naval airmen began to consider that the enemy carriers themselves were logically the principal targets for offensive air operations. Again, the objective of such attacks was not so much to sink the opposing carriers as to cripple their launch and recovery operations by destroying their flight decks at the outset. This, of course, could be accomplished only by aerial attacks of pinpoint accuracy. Sinking carriers could be accomplished, of course, by aerial torpedoes, but not only did such torpedoes continue to exhibit problems of delivery; it was also feared in the Japanese navy that this tactic might well take longer and would thus give the enemy time to fly off his own aircraft. Eventually, as I shall explain in chapter 6, the Japanese navy would work out aerial assault tactics that employed coordinated dive bombing and aerial torpedo runs. In the meantime, dive bombing came to be seen as the best anticarrier tactic in both navies.49

Publicity in the United States given to air shows incorporating dive-bombing demonstrations, supplemented by reports by Japanese naval attachés, was undoubtedly the source of Japanese naval interest in the new tactic. In 1929, at the initiative of Vice Adm. Andō Masataka,† chief of the Naval Aviation Department, the department began gathering basic data concerning the aerial techniques, training, and aircraft needed to develop dive bombing in the Japanese navy. From 1930 to 1932, fighter aircraft carried out a number of dive-bombing attacks against old warship hulks. In 1930, fighters from the First Carrier Division dive-bombed the old cruiser Akashi in Tokyo Bay, using 4-kilogram (8.8-pound) practice bombs, and the next year they attacked the old cruiser Chitose in Saiki Bay, using 30-kilogram (66.2-pound) bombs, a test in which several bombing runs achieved 100 percent accuracy in hitting the target. In 1932 the Yokosuka Air Group and the Naval Air Arsenal began a joint study of dive-bombing techniques, using modified British Bulldog fighters in near-vertical dive-bombing runs against the hulk of the cruiser Aso.50

Okumiya Masatake,† who as a young officer pilot aboard the carrier Ryūjō was one of the first Japanese naval aviators trained in this new tactic, years later remembered the early difficulties in the development of dive bombing, even against stationary land targets. At first, he recalled, dives were made at an angle of 30 degrees from an altitude of 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) and about 2,000 meters (7,000 feet) from the target. A large white cloth was placed on the field and next to it optical equipment that measured dive angles. The young and inexperienced pilots had great difficulty in judging the correct angle for their dives, though after about a month they were able to make dives of 60 degrees. The greatest problem, however, was wind, since changes in wind direction would throw off the pilots’ aim time and again. In high-level bombing, the bombsight automatically corrected for wind at the altitude of the aircraft, but in dive bombing, such correction was not possible, since wind direction was subject to radical change in the midst of a bombing run. Only with experience were dive-bomber pilots able to effectively correct for wind changes.51

As dive-bombing technique developed, it became typical for pilots to begin their dives from a height of about 3,000 meters (10,000 feet), adjusting the angle of their dive, rather than trying to aim, until they were about 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) above the target, by which time they had attained speeds of 250 to 270 knots.52 At that height they adjusted their aiming sights before they reached the release altitude of about 500 meters (1,500 feet). While similar tests were carried out by other air groups over the next several years, the First Carrier Division was assigned the task of translating these attacks by single aircraft on stationary targets into effective tactical doctrine employing coordinated attacks by multiple aircraft against moving warships. In 1935, at the Kashima bombing range on the coast of Ibaraki Prefecture, the navy built a full-size mock-up of the U.S. carrier Saratoga, complete from the flight deck down, on which navy aircraft achieved generally good results in dive-bombing attacks.53 By 1937 the Japanese navy had developed a highly skilled cadre of practitioners of the new art, chief among whom was Lt. Egusa Takashige,† destined to be Japan’s great dive-bombing ace of the Pacific War.54

Despite the fact that in every instance, dive bombing provided greater accuracy against moving targets than horizontal bombing, it became clear that the stress on airframes caused by the violent maneuvers during and after a diving run was far greater than the fighter aircraft, which had been initially used in practice dive-bombing runs, had been designed to take. In trying to find a suitable aircraft for the new tactic, the navy also tried out the Type 90 reconnaissance seaplane, modeled on the American Vought O2U Corsair and adopted for land-based operations, but its dive speed was insufficient.55 What was needed, if dive bombing was to become a standard tactic for the navy, was an aircraft of rugged construction especially designed for the purpose. Thus, in 1933 the navy issued bids for the design and development of a carrier dive bomber56 of exceptional structural integrity and great maneuverability. The contract award was won by Aichi, which through licensing arrangements with Heinkel—which had itself begun designing and building dive bombers—was able to import a Heinkel HE 66 dive bomber. Aichi engineers modified the aircraft to meet the navy’s specifications, including the installation of a Japanese engine and a particularly rugged undercarriage. The result was the Aichi D1A1, a two-man biplane, adopted by the navy in 1934 as the Type 94 carrier bomber. It was soon succeeded by an improved version, the Aichi D1A2, which, as the Type 96 carrier bomber,• was an outstanding aircraft for its day.57

But while the Type 94 was a state-of-the-art aircraft for its time, like contemporary Western dive-bombing aircraft it made physical and mental demands on its crew that in some ways seem outlandish by today’s standards. Okumiya Masatake, as a young lieutenant, was one of the first to fly the Type 94 off the deck of a carrier, the Ryūjō. He has provided us with an understanding of the multiple and often simultaneous tasks required of the crew while on a dive-bombing mission:

In addition to flying the aircraft, the pilot was responsible for carrying out the dive-bombing attack and for firing the two fixed-forward machine guns. His two feet managed the aircraft’s control surfaces, his right hand worked the stick and worked the machine guns; his left managed the engine controls and released the bomb or bombs, all the time looking through the aiming sight. A speaking tube connected to the observer was positioned near his left ear, a radio receiver was positioned at his left and both ears had to constantly monitor the sound of the engine. At his mouth was an oxygen mask, but his nose had to be sensitive to various smells, particularly of gasoline.

For his part, the observer had to handle the radio telegraph, deal with incoming coded messages and decipher them, measure drift, wind speed, and wind direction, calculate the aircraft’s actual speed, determine its actual position. When necessary, he also had to fire the flexible rear-firing machine gun, take photographs, drop message bags, use flag or flash signals, and, when in a dive, assist the pilot by reading off the angle of dive.58

This is multitasking at its most horrendous!

In any event, with the appearance of the Aichi D1A1, dive bombing came into its own in the Japanese navy.59 In 1935 the navy had begun to practice formation dive bombing and to experiment with a formula whereby carrier fighters would stay above the dive bombers as a cover force while the latter dove into the attack. But controversy over the superiority of dive bombing as opposed to torpedo bombing, which had begun soon after the formation of the First Carrier Division in 1928, was to grow in intensity during the succeeding decade. The only way to resolve the debate conclusively would have been to study the results of a number of actual combat situations in which each was used. In the absence of such wartime proof, the advocates of each tactic merely made self-serving arguments concerning the great contribution it would make to winning the decisive battle at sea.60 Eventually, as we shall see, the Japanese navy was to work out a powerful offensive system of coordinated mass assaults by fighter aircraft, dive bombers, and torpedo planes that was practiced repeatedly and with great precision by the navy in the years immediately prior to the Pacific War.

THE ROLE OF THE FIGHTER IN JEOPARDY

In the 1920s the Japanese navy gave little thought to the use of fighter aircraft in an offensive capacity. Given the fact that the fighters of the time had very short ranges and thus seemed to have little use in blue-water operations, and the fact that for most of the decade Japan had only one small carrier to embark them, the navy’s indifference is not surprising. It was, however, a marked contrast to the attitude in the Japanese army. Reviewing the lessons of air warfare over the Western Front during World War I, the army air service concluded that fighter aircraft were the main elements of air power. In the 1920s, therefore, it was the Japanese army, rather than the navy, that made the greatest progress in developing air combat tactics. Army airmen studied European fighter tactics extensively in the immediate postwar years, and in 1927 and 1929, instructors from France were invited to give lectures on the subject.61 In the navy, for the most part, air combat technique during the 1920s did not progress much beyond the introductory training provided by the Sempill Mission at the outset of the decade.

By the end of the decade, with the acquisition of the large carriers Akagi and Kaga, the navy did begin to undertake a number of efforts to improve the aerial combat skills of its fighter service for advanced training. Lt. Nakano Chūjirō† was sent to the army’s Air Gunnery School at Akeno and Lt. Kamei Yoshio to Britain. Upon their return, in a series of special training exercises held at the Yokosuka Naval Air Base in December 1929, they undertook to pass on to other pilots the techniques they had mastered. These exercises, which brought together pilots and instructors from the Yokosuka, Ōmura, and Kasumigaura naval air groups, as well as from the carriers Kaga and Hōshō, included training in aerial gunnery, single aircraft combat, single versus multiple aircraft tactics, aircraft attacks from various approaches, and some formation tactics. Moreover, the Japanese navy still believed that it had much to learn from foreign instruction in air combat skills. In the autumn of 1930, at the navy’s invitation, two officers from Britain’s Royal Air Force offered a five-month course in fighter tactics, with special emphasis on gunnery. This was followed in 1931 by a six-month training program in aircraft weapons and their maintenance, also provided by RAF personnel.62

Over the next two or three years the leading air groups of the naval air service selected their best pilots for participation in frequent and intensified training programs, exercises, and drills in fighter combat, held by the Yokosuka Air Group fighter squadron and largely centered around single plane-to-plane combat. Out of this rigorous and competitive training environment there emerged a number of highly skilled and motivated fighter pilots—officers like Kamei Yoshio, Kobayashi Yoshito,† Okamura Motoharu,† and Genda Minoru†—who by the late 1930s came to shape the navy’s fighter doctrine and who eventually commanded some of the navy’s best air groups in the Pacific War.63 Starting about 1932, some gained fame as members of special flight teams that barnstormed the country, demonstrating their acrobatic skills during subscription ceremonies held to raise money for the public donation of aircraft to the nation. A three-man team led by Lieutenant Kobayashi and known as the “Sky Circus” was formed in 1931. In 1932 it expanded to include nine members under the leadership of Lieutenant Genda and became known as the “Genda Circus.” Lieutenant Okamura was to form his own “circus” later that year.64

The mid-1930s were golden years for the development of fighter tactics at Yokosuka, as these young men took their biplane fighters aloft day after day to pit their skills against each other and to try out new aerial dogfighting techniques. It was about this time that Mochizuki Isamu,† a flight petty officer at the time, developed one of the most brilliant of these schemes—the hineri-komi (literally, “turning in”), a half loop and roll—with which he time and again bested the famed Genda himself. Essentially it was technique by which a fighter pilot with an enemy on his tail could, by several deft and sudden maneuvers, quickly take a firing position astern of the enemy. To perform it, Mochizuki would pull up into a loop. Just before the apex of the loop he would sideslip out of the loop, cutting down on his turning radius significantly and thus putting himself on the tail of his enemy. (See app. 9 for an illustrated explanation of the maneuver.) The significance of the maneuver, which was to be demonstrated early on in the navy’s air war in China, was that it allowed an aircraft of lesser turning ability to make up the difference with an aircraft of superior turning performance. Eventually adopted by all Japanese navy fighter units and by Japanese army fighter pilots as well, it was the only original aerial tactic developed by the Japanese that was not known to foreign pilots before the Pacific War.65

Thus, by the mid-1930s the Yokosuka Naval Air Base had become the mecca of fighter pilots and the pioneering center for the development of fighter tactics. More important, the Japanese naval air service as a whole had begun to pull even with the Japanese army in air combat capabilities. Indeed, the growing skill of the navy’s pilots was demonstrated in the joint training exercises held by the two air services from 1934 to 1936. Ostensibly the maneuvers were a matter of cooperative training in aerial combat; in practice they were a manifestation of the intense competition born of traditional interservice rivalry and the divergence of tactics, equipment, and training principles. The many dogfights involved in the first exercises, held in 1934 at Yokosuka, produced a draw between the two services. But in the more complex exercises held at Akeno in 1935 and again at Yokosuka in 1936, navy pilots are said by Genda Minoru to have completely outclassed their army counterparts.66 While the China War forced the termination of these interservice air competitions, by 1937 it was clear that the navy’s fighter arm had come of age.

Yet even as the air combat skills of its aircrews were improving in the early 1930s, the navy, and its air service in particular, had begun to doubt the value of its carrier fighter units. In part this was due to the traditional preference in the Japanese navy for offensive operations, for which the bombing plane was admirably suited and the fighter plane, in its defensive role, was not. When Lt. Comdr. Shibata Takeo,† a leading fighter pilot, tried to point out to a Navy General Staff officer the importance of fighters in defending the fleet, the latter shot back a stinging rebuke against defensive tactics: “And you claim to be a Japanese!”67 Doubts about the viability of fighters were also due to a condition that appears to have been perceived by all the world’s air powers during these years: the generally inferior performance of fighter aircraft in relation to bombing planes.68 First of all, there was no possibility of using fighters in an offensive role, since most carrier fighters of the day had a range of not much more than 100–150 miles. They would be unable to provide cover for carrier bombers, whose average range was over 200 miles. But even in a defensive role, the existing fighter aircraft seemed at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the bomber. Increasingly Japanese pilots came to believe that fighters would have difficulty carrying out the maneuvers necessary to bring down enemy bombers without at least a 30 percent superiority in speed. By this standard, they judged that the fighter aircraft they flew—generally the Nakajima A2N (Type 90) and the Nakajima A4N (Type 95)• carrier fighters,69 while among the best in the world at the time, were still too slow and underarmed, as demonstrated time and again in gunnery training when targets moved too fast for fighter planes to make many hits.

For these reasons there arose, in about 1934, a general opinion among fighter pilots at Yokosuka that fighters really no longer had an operational role, a sentiment shared by some of the navy’s best fliers, including Genda Minoru. This view intensified with the appearance in 1936 of the radically designed twin-engined Mitsubishi G3M (Type 96 “Nell”) medium bomber,• whose speed and range surpassed any aircraft Japan had produced up to that point. (See chap. 4.) In air maneuvers in April 1937, a fighter squadron was given the task of defending the Sasebo Naval Base from the attack of a flight of G3M bombers flying in from Kanoya. As it turned out, the raid was judged a complete success, the defending fighters failing to get in a single blow. To many, such events were proof that fighters ought to be abolished and carrier decks given completely over to attack aircraft.70

As we have seen, the Japanese navy, like the British and American navies, had given thought in the early 1930s to using fighters as dive bombers for the sake of speed and fuel efficiency, and in 1933 Genda Minoru himself had advocated that serious study be given to this possibility. But at a time when the concept of the decisive surface battle had apparently hardened into dogma and the principal duty of carrier fighters accompanying the main force was seen to be clearing the skies of enemy aircraft over the battle area, the navy concluded that it was not possible to spare fighter aircraft for any other purpose.71

Yet there were airmen in the Japanese navy at this time who maintained that the fighter still had a vital role to play in air operations and that its current problems could be solved by changes in tactics, design, and command and communications systems. Lieutenant Commander Shibata, at that time a division officer at the Ōmura Air Group and a bitter rival of Genda Minoru, was one of these. In his view, one of the reasons that skilled fighter pilots at Yokosuka had trouble hitting targets towed at high speed during the training exercises was that exercise rules forbade attacking aircraft from approaching at an angle of less than 20 degrees from the line of flight of the target (for fear of hitting the plane towing the target). This unreasonable and unrealistic restriction, he argued, prevented pilots from attacking from astern and momentarily holding the target in their sights, as could happen in actual combat. Shibata argued, moreover, that current navy air combat manuals presented a false bias in favor of bombing aircraft. The superior speed of bombing aircraft could be overcome, he insisted, by changing tactics, such as attacking from the rear—which would dramatically increase the number of hits—or aiming at the most vulnerable parts of the enemy aircraft: its wing tanks.72

Shibata and another officer at Ōmura, Comdr. Ikegami Tsuguo,† also concluded that an essential reason for the inferiority of defending fighters to attacking bombers lay in the lack of any early-warning system that would enable defending fighters to spot an approaching enemy first. While this was a universal problem for the fighter commands of all the world’s air powers and would not be solved until the perfection of radar, at the time Shibata and Ikegami held that intensive effort needed to be given to improving intelligence, aircraft communications, and command and control aboard Japan’s aircraft carriers. In the meantime, much could and should be done to redesign the single-seat fighter. This meant increasing its speed, maneuverability, and armament, to give it a margin of superiority over bombers. Ultimately, of course, Japanese fighter plane designers would be forced to concentrate on only one of these three capabilities in which to achieve outstanding performance.73

In early 1933 the testing of the Type 90 carrier fighter and the identification of its defects had provoked what was to become a famous and prolonged debate among the navy’s fighter pilots as to the proper emphasis for fighter design: speed or maneuverability. The controversy originated as an argument over the performance and maneuverability of the Type 90, which had proved superior to the Type 3 but inferior in speed to a modified version of the British Bulldog fighter plane. To improve the Type 90, one group of navy pilots had advocated increasing the wing area in order to decrease the wing loading. In a memorandum criticizing the intricate dogfighting tactics of the Yokosuka Air Group, Lt. Comdr. Odawara Toshihiko,† who had been a test pilot for the Flight Testing Department of the Naval Air Arsenal, opposed this idea, saying that any decrease in wing loading should be accomplished by reevaluating the structural materials of the aircraft in order to lighten it for greater speed. His statement provoked a storm of controversy and a heated response from Comdr. Okamura Motoharu, who had his own “Flying Circus” at Yokosuka. Okamura attacked Odawara’s ideas as unsound and insisted that speed and rate of climb were less important factors in the design of a fighter plane than maneuverability. Odawara’s counterblast in another memorandum provoked Okamura to challenge him to a mock combat fly-off (which never took place) and split Japanese naval fighter pilots and designers into two camps.74

The Yokosuka Air Group was at the center of the controversy, and tests that its pilots ran convinced them of the superior importance of maneuverability. As a result, maneuverability became the supreme design criterion for fighters after 1935, though challenges to this view came forth again during the China War.75 Lt. Comdr. Sawai Hideo, staff officer of the Naval Aviation Department, and others believed that the Japanese navy failed to produce a superior fighter in the mid-1930s, but they did not blame the emphasis on maneuverability. If anything, they championed it. For them, the lack of distinction in Japanese designs in this period resulted from hasty design and production as well as the General Staff’s interference. The urgings of perceptive officers in the Aviation Department like Commander Sawai and the testimony of pilots in the air war over China after July 1937 eventually produced a dramatic improvement in Japanese fighter designs. Their efforts led, as we shall see, to the design and development of Japan’s first all-metal monoplane fighter, the Mitsubishi A5M (Type 96) carrier fighter,• an aircraft that gained fame because of its great maneuverability.76

RECONNAISSANCE AIRCRAFT

In this assessment of the evolution of Japanese naval air tactics and related technology from their beginnings up to the mid-1930s, it remains only to comment briefly upon the development of the navy’s aerial search capabilities.77 This had been the raison d’être for Japanese naval aviation at its beginning. During World War I, ship-borne (though not ship-launched) reconnaissance seaplanes had been used on a number of search missions, and after the war a number of long-range reconnaissance training flights from Yokosuka to Okinawa and to the Chinkai Naval Base in Korea had demonstrated the potential value of aerial reconnaissance for fleet operations.78 Japan’s first carrier, the Hōshō, had been built with the idea of scouting and reconnaissance very much in mind. Logically, the importance of scouting should have grown with the increasing role for carrier aviation and the imperative of launching a first strike against enemy carriers. Yet, as I shall explain in a later chapter, the Japanese navy failed to develop reconnaissance as a primary function of carrier aviation because its increasing fixation on offensive operations, and attack planes sacrificed the hangar space available for reconnaissance aircraft.

But the navy’s dilemma, as it began to assemble a carrier force during the interwar years, was similar to that of the American and British navies in the same period. All three navies were keenly aware of the limited capacity of carriers and were chary of using up precious space on board for anything other than fighters and attack aircraft. Given its emphasis on offensive operations, the Japanese navy was particularly reluctant to do so. Nevertheless, the navy attempted to develop reconnaissance aircraft with sufficient capabilities to warrant a place on carriers. But the models that were produced continually proved inferior in performance to the attack aircraft the navy adopted.79 The first plane officially designated as a “C” (reconnaissance) aircraft was the C1M1/C1M2 (Type 10) designed for Mitsubishi by the British aircraft engineer Herbert Smith. It was accepted by the navy in 1922 but could not match the performance of the Mitsubishi B1M (Type 13) shipboard attack aircraft (torpedo bomber) when the latter came into service in 1924 and thus was not incorporated into Japanese carrier air groups. The B1M was used not only for torpedo bombing but also for scouting missions. In 1935 the navy tried again and ordered Nakajima to design a specialized reconnaissance aircraft. The result was the Nakajima C3N1, which after carrier trials was actually accepted as the Type 97 shipboard reconnaissance aircraft. But once again, the superior capabilities of an attack aircraft crowded out the reconnaissance aircraft from the navy’s carrier decks. The navy’s new torpedo bomber, which eventually became the B5N (Type 97) shipboard attack aircraft,• performed comparably to the C3N1, which was dropped by the navy after the building of only two prototype models. As a result, the B5N was given double responsibilities as an attack and reconnaissance aircraft.80 It was not until the advent of the Nakajima C6N1 “Saiun” in 1942 that the Japanese navy finally had a specially designated reconnaissance aircraft with sufficient performance to justify making room for it in carrier complements.