We may never know exactly what the common people of ancient times believed about the stars. We can read the translations of the works of the scribes, but what about the shepherds, the nomads, and the people in the ages before writing existed? They must have noticed that stars come in a variety of brightnesses and colors. Even though the stars seem to be scattered randomly (unless the observer knows that the Milky Way is a vast congregation of stars), identifiable star groups exist. These star groups do not change within their small regions of the sky, although the vault of the heavens gropes slowly westward night by night, completing a full circle every year. These star groups and the small regions of the sky they occupy are called constellations.

We know that the constellations are not true groups of stars but only appear that way from our Solar System. The stars within a constellation are at greatly varying distances. Two stars that look like they are next to each other really may be light-years apart (a light-year is the distance light travels in a year) but nearly along the same line of sight. As seen from some other star in this part of the galaxy, those two stars may appear far from each other in the sky, maybe even at celestial antipodes (points 180 degrees apart on the celestial sphere). Familiar constellations such as Orion and Hercules are their true selves only with respect to observers near our Sun. Interstellar travelers cannot use the constellations for navigation.

Many of the constellations are named for ancient Greek gods or for people, animals, or objects that had special associations with the gods. Cassiopeia is the mother of Andromeda. Orion is a hunter; Hercules is a warrior; Draco is a dragon. There are a couple of bears and a couple of dogs. There is a sea monster, most likely a crazed whale, who almost had Andromeda for supper one day. There is a winged horse, a pair of fish whose tails are attached, a bull, a set of scales used to mete out cosmic justice, a goat, twin brothers who look after ocean-going vessels, and someone pouring water from a jug that never goes empty. The Greeks saw a lot of supernatural activity going on in the sky. They must have thought themselves fortunate that they were far enough away from this lively circus so as not to be kept awake at night by all the growling, barking, shouting, and whinnying. (If the ancient Greeks knew what really happens in the universe, they would find the shenanigans of their gods and animals boring in comparison.)

The people of Athens during the age of Pericles saw the exact same constellations that we see today. You can look up in the winter sky and recognize Orion immediately, just as Pericles himself must have. The constellations, as you know them, will retain their characteristic shapes for the rest of your life and for the lives of your children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. In fact, the constellations have the same shapes as they did during the Middle Ages, during the height of the Roman Empire, and at the dawn of civilization, when humans first began to write down descriptions of them. The positions of the constellations shift in the sky from night to night because Earth revolves around the Sun. They also change position slightly from century to century because Earth’s axis slowly wobbles, as if our planet were a gigantic, slightly unstable spinning top. But the essential shapes of the constellations take millions of years to change.

By the time Orion no longer resembles a hunter but instead perhaps a hunched old man or a creature not resembling a human at all, this planet likely will be populated by beings who look back in time at us as we look back at the dinosaurs. As life on Earth evolves and changes shape, and as the beings on our planet find new ways to pass through life, so shall the mythical deities of the sky undergo transformations. Perhaps Orion will become his own prey, and Draco will be feeding Hercules his supper every evening.

In this chapter, the general shapes of the better-known constellations are shown. To see where these constellations are in the sky from your location this evening, go to the Weather Underground Web site at the following URL:

http://www.wunderground.com

Type in your ZIP code or the name of your town and state (if in the United States) or your town and country and then, when the weather data page for your town comes up, click on the “Astronomy” link. There you will find a detailed map of the entire sky as it appears from your location at the time of viewing, assuming that your computer clock is set correctly and data are input for the correct time zone.

Celestron International publishes a CD-ROM called The Sky, which shows stars, planets, constellations, coordinates, and other data for any location on Earth’s surface at any time of the day or night. This CD-ROM can be obtained at hobby stores that sell Celestron telescopes.

Imagine that you’re stargazing on a clear night from some location in the mid-northern latitudes, such as southern Europe, Japan, or the central United States. Suppose that you sit down and examine the constellations on every clear evening, a couple of hours after sunset, for an entire year. Sometimes the Moon is up, and sometimes it isn’t. Its phase and brightness affect the number of stars you see even on the most cloud-free, haze-free nights. But some constellations stand out enough to be seen on any evening when the weather permits. The constellations near the north celestial pole are visible all year long. The following subsections describe these primary constellations.

In this chapter, stars are illustrated at three relative levels of brightness. Dim stars are small black dots. Stars of medium brilliance are larger black dots. Bright stars are circles with black dots at their centers. But the terms dim, medium, and bright are not intended to be exact or absolute. In New York City, some of the dim stars shown in these drawings are invisible, even under good viewing conditions, because of scattered artificial light. After your eyes have had an hour to adjust to the darkness on a moonless, clear night in the mountains of Wyoming, some of the dim stars in these illustrations will look fairly bright. The gray lines connecting the stars (reminiscent of dot-to-dot children’s drawings) are intended to emphasize the general shapes of the constellations. The lines do not, of course, appear in the real sky, although they are often shown in planetarium presentations and are commonly included in sky maps.

One special, moderately bright star stays fixed in the sky all the time, day and night, season after season, and year after year. This star, called Polaris, or the pole star, is a white star of medium brightness. It can be found in the northern sky at an elevation equal to your latitude. If you live in Minneapolis, for example, Polaris is 45 degrees above the northern horizon. If you live on the Big Island of Hawaii, it is about 20 degrees above the horizon. If you live in Alaska, it’s about 60 to 65 degrees above the horizon. At the equator, it’s on the northern horizon. People in the southern hemisphere never see it.

Polaris makes an excellent reference for the northern circumpolar constellations and in fact for all the objects in the sky as seen from any location in Earth’s northern hemisphere. No matter where you might be, if you are north of the equator, Polaris always defines the points of the compass. Navigators and explorers have known this for millennia. You can use the pole star as a natural guide on any clear night.

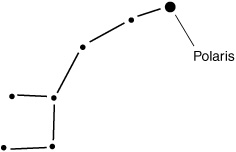

Polaris rests at the end of the “handle” of the so-called little dipper. The formal name for this constellation is Ursa Minor, which means “little bear.” One might spend quite a while staring at this constellation before getting the idea that it looks like a bear, but that is the animal for which it is named, and whoever gave it that name must have had a reason. Most constellations are named for animals or mythological figures that don’t look anything like them, so you might as well get used to this. The general shape of Ursa Minor is shown in Fig. 2-1. Its orientation varies depending on the time of night and the time of year.

Figure 2-1. Ursa Minor is commonly known as the “little dipper.”

The so-called big dipper is formally known as Ursa Major, which means “big bear.” It is one of the most familiar constellations to observers in the northern hemisphere. In the evening, it is overhead in the spring, near the northern horizon in autumn, high in the northeastern sky in winter, and high in the northwestern sky in summer. It, like its daughter, Ursa Minor, is shaped something like a scoop (Fig. 2-2). The two stars at the front of the scoop are Dubhe and Merak, and are called the pointer stars because they are roughly aligned with Polaris. If you can find the big dipper, look upward from the scoop five or six times the distance between Dubhe and Merak, and you will find Polaris. To double-check, be sure that the star you have found is at the end of the handle of the little dipper.

Figure 2-2. Ursa Major, also called the “big dipper,” is one of the best-known constellations in the heavens.

One of the north circumpolar constellations is known for its characteristic M or W shape (depending on the time of night and the time of year it is viewed). This is Cassiopeia, which means “queen.” Ancient people saw this constellation’s shape as resembling a throne (Fig. 2-3), and this is where the idea of royalty came in. In the evening, Cassiopeia is low in the north-northwestern sky in the spring, moderately low in the north-northeastern sky in the summer, near the zenith in the fall, and high in the northwestern sky in the winter.

Figure 2-3. Cassiopeia, also called the “queen,” looks like the letter M or the letter W. To the ancients, it had the shape of a throne.

As the queen sits on her throne, she faces her spouse, the king, the constellation whose formal name is Cepheus. This constellation is large in size but is comprised of relatively dim stars. For this reason, Cepheus is usually obscured by bright city lights or the sky glow of a full moon, especially when it is near the horizon. It has the general shape of a house with a steeply pitched roof (Fig. 2-4). In the evening, Cepheus is near the northern horizon in the spring, high in the north-northeast sky in the summer, nearly overhead in the fall, and high in the northwestern sky in the fall.

Figure 2-4. Cepheus, the “king,” resides in front of Cassiopeia’s throne. It has the shape of a house with a steep roof.

One of the largest circumpolar constellations, obscure to casual observers on account of its long, winding shape, is Draco, the dragon. With the exception of Eltanin, a star at the front of the dragon’s “head,” this constellation is made up of comparatively dim stars (Fig. 2-5). Draco’s “tail” wraps around the little dipper. The big dipper is in a position to scoop up the dragon tail first. In the evening, Draco is high in the northeastern sky in springtime, nearly overhead in the summer, high in the north-northwest sky in the fall, and near the northern horizon in the winter.

Figure 2-5. Draco, the “dragon,” has a long, sinuous shape with an obvious “head” and “tail.”

Perseus is another circumpolar constellation with an elongated, rather complicated shape (Fig. 2-6). A mythological hero, Perseus holds the decapitated head of Medusa, a mythological female monster with hair made of snakes and a countenance so ugly that anyone who looked on it was turned into stone. Perseus is low in the northwestern sky in springtime, half above and half below the northern horizon in the summer, high in the northeastern sky in the fall, and nearly overhead in the winter.

Figure 2-6. Perseus is a mythological hero who holds the severed head of Medusa. Its star Algol varies in brilliance because it is actually two stars that eclipse each other as they orbit around a common center of gravity.

There are other, lesser constellations that remain above the horizon at all times. These can be found on star maps. The further north you go, the more circumpolar constellations there are. If you were to go all the way to the north pole, all the constellations would be circumpolar. The stars would all seem to revolve around the zenith, completing one full circle every 23 hours and 56 minutes. Conversely, the further south you go, the fewer circumpolar constellations you will find. At the equator, there are none at all; every star in the sky spends half the sidereal day (about 11 hours and 58 minutes) above the horizon and half the sidereal day below the horizon.

We haven’t discussed what happens if you venture south of the equator. But we will get to that in the next chapter.

Besides the circumpolar constellations, there are certain star groups that are characteristic of the evening sky in spring in the northern hemisphere. The season of spring is 3 months long, and even if you live in the so-called temperate zone, your latitude might vary. Thus, to get ourselves at a happy medium, let’s envision the sky in the middle of April, a couple of hours after sunset at the latitude of Lake Tahoe, Indianapolis, or Washington, D.C. (approximately 39° N).

Libra is near the east-southeastern horizon. It has the general shape of a trapezoid (Fig. 2-7) if you look up at it facing toward the east-southeast. Libra is supposed to represent the scales of justice. This constellation is faint and once was considered to be part of Scorpio, the scorpion.

Figure 2-7. Libra, the scales of justice.

Virgo, the virgin, is fairly high in the southeastern sky. It has an irregular shape, something like a letter Y with a hooked tail (Fig. 2-8) if you look up at it facing toward the southeast. Virgo contains the bright star Spica.

Figure 2-8. Virgo, the virgin, holds a staff of wheat.

Leo, the lion, is just south of the zenith. This constellation is dominated by the bright star Regulus. If you stand facing south and crane your neck until you’re looking almost straight up, you might recognize this constellation by its Sphinx-like shape (Fig. 2-9).

Figure 2-9. Leo, the lion, resembles the Sphinx.

Cancer, the crab, stands high in the southwestern sky. If you stand facing southwest and look up at an elevation about 70 degrees, you’ll see a group of stars that resembles an upside-down Y (Fig. 2-10). In ancient mythology, Cancer was the cosmic gate through which souls descended to Earth to occupy human bodies. Next to Cancer is Canis Minor, the little dog, which contains the prominent star Procyon.

Figure 2-10. Cancer, the crab; and Canis Minor, the little dog.

Gemini is moderately high in the western sky. This constellation has the general shape of a tall, thin, squared-off letter U if you stand facing west and look up at it (Fig. 2-11). At the top of the U are the prominent stars Castor and Pollux, named after the twin sons of Zeus, the most powerful of the ancient Greek gods. If you use your imagination, you might see Castor facing toward the left, with Pollux right behind him. The bright stars must be their left eyes.

Just to the right of Gemini is the constellation Auriga. It has the shape of an irregular pentagon (Fig. 2-12) as you face west-northwest and look upward about 30 degrees from the horizon. Auriga contains the bright star Capella. In ancient mythology, this constellation represented the king of Athens driving a four-horse chariot. Presumably, Capella is the king, and the four lesser stars are the horses.

Figure 2-11. Gemini. The stars Pollux and Castor represent the twins.

Figure 2-12. Auriga, the charioteer.

Turn around and look toward the east-northeast, just above the horizon. You will see a complex of stars, none of them bright, forming a trapezoid with limbs (Fig. 2-13). This is the constellation Hercules, representing a man of legendary strength and endurance. In the sky, he faces Draco, the dragon. These two cosmic beings are engaged in a battle that has been going on for millennia and will continue to rage for ages to come. Who will win? No one knows, but eventually, as the stars in our galaxy wander off in various directions, both these old warriors will fade away. Hercules contains one of the most well-known star clusters in the heavens, known as M13 (this is a catalog number).

Figure 2-13. Hercules, the warrior, is in a long, cosmic battle with Draco.

Looking slightly higher in the sky, just behind Hercules, you will see a group of several stars that form a backward C or horseshoe shape. These stars form the constellation Corona Borealis, the northern crown (Fig. 2-14). This is the head ornament that was worn by Ariadne, a princess of Crete. According to the legends, the Greek god Dionysis threw the crown up into the sky to immortalize the memory of Ariadne.

Figure 2-14. Corona Borealis, the crown worn by Ariadne, princess of Crete.

Just above the northern crown you will see a bright star at an elevation of about 45 degrees, directly east or a little south of east. This is Arcturus. If you use your imagination, you might see that this star forms the point where a fish joins its tail; the fish appears to be swimming horizontally (Fig. 2-15). This constellation, Bootes, does not represent a fish but a herdsman. His job, in legend, is to drive Ursa Major, the great bear, forever around the north pole.

Figure 2-15. Bootes, the herdsman, and his hunting dogs, Canes Venatici.

Between Bootes and Ursa Major there is a group of three rather dim stars (shown in Fig. 2-15 along with their master). These are Bootes’ hunting dogs, Canes Venatici, who snap at the heels of Ursa Major and keep the big bear moving. One might argue that according to myth, our planet owes its rotation, at least in part, to a couple of cosmic hounds.

A large portion of the spring evening sky is occupied by three constellations consisting of relatively dim stars. These are Corvus, also known as the crow, Crater, also called the cup, and Hydra, the sea serpent or water snake (Fig. 2-16). It is not too hard to imagine how Hydra got its name, and one might with some effort strain to imagine Crater as a cup. But Corvus is a fine example of a constellation that looks nothing like the mythological creature or object it represents.

Figure 2-16. Corvus, the crow; Crater, the cup; and Hydra, the sea serpent.

Now let’s look at the sky in the middle of July, a couple of hours after sunset at the latitude of Lake Tahoe, Indianapolis, or Washington, D.C. (approximately 39° N). Some of the spring constellations are still visible. All the circumpolar constellations are still there, but they appear to have rotated around Polaris one-quarter of a circle counterclockwise from their positions in the spring. Other spring constellations that are still visible, though they have moved toward the west the equivalent of about 6 hours, include Virgo, Libra, Bootes, Canes Venatici, Corona Borealis, and Hercules. New star groups have risen in the east, and old ones have set in the west. Here are the prominent new constellations of summer.

Near the horizon in the east-southeast sky is a group of stars whose outline looks like the main sail on a sailboat. This constellation is Capricornus (often called Capricorn), the goat (Fig. 2-17). This goat has the tail of a fish, according to the myths, and dwells at sea. On its way to heaven after the death of the body, the human soul was believed to pass through this constellation; it is 180 degrees opposite in the celestial sphere from Cancer, through which souls were believed to enter this world.

Figure 2-17. Capricornus, the goat, has the tail of a fish.

In the east-southeast sky, to the right and slightly above Capricornus, you will see a constellation whose outline resembles a teapot (Fig. 2-18). This is Sagittarius, the centaur. What, you might ask, is a centaur? You ought to know if you have read mythology or seen a lot of movies or television; it is a creature with the lower body of a horse and the chest, head, and arms of a human being. The centaur carries a bow and arrow with which to stun evil or obnoxious creatures. Sagittarius lies in the direction of the densest part of the Milky Way, the spiral galaxy in which our Solar System resides.

Figure 2-18. Sagittarius, the centaur, is shaped like a teapot as viewed from northern-hemispheric temperate latitudes.

A huge and hapless scorpion, forever on the verge of feeling the bite of Sagittarius’s arrow, sits in the southern sky, extending from near the horizon to an elevation of about 30 degrees (Fig. 2-19). This is Scorpius (also called Scorpio). This constellation is one of the few that bears some resemblance to the animal or object it represents. The eye of the scorpion is the red giant star Antares, which varies in brightness.

Figure 2-19. Scorpius, the scorpion, contains the red star Antares.

If you stand facing east and look up near the zenith, you will see the bright star Vega, flanked by a small parallelogram of dimmer stars. The quadrilateral forms the constellation Lyra, representing the lyre played by the mythical musician Orpheus. Below and to the left of Vega is another bright star, Deneb, that is at the tip of the tail of Cygnus, the swan. If you are at a dark location away from city lights on a moonless summer evening, you might imagine this bird soaring along the Milky Way that stretches from the north-northeastern horizon all the way to the southern horizon. Off to the right of these is a third bright star, Altair. This is part of the constellation Aquila, the eagle that pecks eternally at the liver of Prometheus as part of his punishment for stealing fire from the gods. Vega, Deneb, and Altair stand high in the east on summer evenings and comprise the well-known summer triangle (Fig. 2-20).

In the southern sky, centered at the celestial equator, is the constellation Ophiuchus, the snake bearer. This poor soul holds a snake, the constellation Serpens, that stretches well to either side. You might imagine that Ophiuchus has a meaningless job, but nothing could be further from the truth. Ophiuchus must keep a tight hold on Serpens (Fig. 2-21), for if that snake gets away, it will easily be able to reach and bite Bootes, the herdsman. If that were to happen, Bootes and his dogs, Canes Venatici, would stop driving Ursa Major around Polaris, and Earth would stop spinning!

Figure 2-20. The Summer Triangle is formed by the stars Vega, Deneb, and Altair, in the constellations Lyra, Cygnus, and Aquila (the lyre, the swan, and the eagle).

Figure 2-21. Ophiuchus, the serpent bearer, holds Serpens, the snake. The snake’s head is but a small distance from the back of unsuspecting Bootes.

About halfway between the horizon and the zenith in the west-northwest sky, you will see a fuzzy blob. With binoculars, this resolves into a cluster of stars known as Coma Berenices (the hair of Berenice). Some people mistake this group of stars for the Pleiades. However, the Pleiades are best observed in the winter.

Now imagine that it is an evening in the middle of October, a couple of hours after sunset, and you are at the latitude of Lake Tahoe, Indianapolis, or Washington, D.C. (approximately 39° N). New constellations have risen in the east, and old ones set in the west. The sky is looked after by new custodians as the nights grow longer. Here are constellations we have not described before that now occupy prominent positions in the sky.

High in the southeast you will see Pisces, the two fish, and Aries, the winged ram (Fig. 2-22). Legend has it that Pisces were joined or tied together at their tails long ago, and to this day they are flailing about in that unfortunate condition. Aries has fleece of gold, and for this reason, the ram is sought after by a cosmic spirit called Jason and his cohorts called the Argonauts.

Somewhat below and to the right of Pisces is Cetus, the whale, also considered a sea monster in some myths (Fig. 2-23). The variable star Mira is sometimes visible in the belly of the whale. Cetus is supposed to have been sent to swallow Andromeda, but this mission did not succeed. Cetus contains one star, called Tau Ceti, believed to be a good candidate for having a solar system similar to ours.

Figure 2-22. Pisces, the fishes, and Aries, the ram.

Figure 2-23. Cetus, the whale, contains the variable star Mira.

Nearly at the zenith there is a square consisting of four medium-bright stars. This is the body of Pegasus, the winged horse. Toward the northeast, Andromeda, representing a princess, rides the horse alongside the Milky Way (Fig. 2-24). Andromeda had been chained to a rock and left out for Cetus to devour as the tide came in, but she was rescued by Perseus. Andromeda contains a spiral galaxy similar to our Milky Way but is more than 2 million light-years away. This galaxy can be seen as a dim blob by people with keen eyesight; with a massive telescope at low magnification, it resolves into a spectacular object. When photographed over a period of hours, it takes on the classic appearance of a spiraling disk of stars.

Figure 2-24. Pegasus, the winged horse, and Andromeda, the Ethiopian princess who married Perseus. The Andromeda Galaxy is shown as a fuzzy dot.

Beneath Pegasus, in the southern sky, you will see Aquarius, the water bearer. This is not an easy constellation to envision as any sort of human figure; it more nearly resembles an exotic, long-necked bottle or a tree branch (Fig. 2-25). Aquarius supposedly brings love and peace as well as water.

Low in the southern sky is Piscis Austrinus, also called Piscis Australis. This is the southern fish and contains the bright star Formalhaut (Fig. 2-26). At the middle temperate latitudes in North America, Piscis Austrinus manages to rise only a few degrees above the horizon. Further north, in Europe and in England, it barely emerges at all. Immediately to the south of it is Grus, the crane. This constellation is not visible in the northern temperate extremes, although it can be seen on dark nights in most of the United States.

Figure 2-25. Aquarius, the water-bearer, traverses the southern sky on autumn evenings.

Figure 2-26. Piscis Austrinus, the southern fish, and Grus, the crane. At latitudes higher than about 45 degrees north, Grus never rises above the southern horizon.

Finally, let’s get our jackets on and look at the evening sky in the middle of January. Some of the autumn constellations can still be seen. The circumpolar constellations have rotated around Polaris by yet another quarter circle and are now 90 degrees clockwise relative to their positions in the spring. Here are the prominent new constellations of winter as they appear from the latitude of Lake Tahoe, Indianapolis, or Washington, D.C. a few hours after suppertime.

The southern portion of the winter evening sky is dominated by Canis Major, the big dog, and Lepus, the rabbit (Fig. 2-27.) Canis Major is easy to spot because of the brilliant white star, Sirius, that appears in the south-southeast. This is the brightest star in the whole sky, and its name in fact means “scorching.” Because it is contained in Canis Major, Sirius is often called the Dog Star.

Figure 2-27. Canis Major, the big dog, and Lepus, the rabbit.

Somewhat above and to the right of Sirius you will see another winter landmark, Orion, the hunter. It’s not hard to imagine how ancient people saw a human form in this constellation (Fig. 2-28). Three stars in the middle of Orion represent the hunter’s belt, from which hangs a knife or sword consisting of several dimmer stars. If you look at Orion’s sword with good binoculars or a wide-aperture telescope at low magnification, you will see the Great Nebula in Orion, a vast, glowing cloud of gas and dust in which new stars are being born. Orion contains two bright stars of its own, Betelgeuse (also spelled Betelgeux), a red giant, and Rigel, a blue-white star.

Figure 2-28. Orion, the hunter, is one of the best-known constellations. It contains a nebula that is visible with good binoculars.

Above Orion, only a few degrees from the zenith in the southern sky on winter evenings, is Taurus, the bull (Fig. 2-29). This constellation contains the bright star Aldebaran, which represents the eye of the bull. Near Taurus is a group of several stars known as the Pleiades, or seven sisters (although there are really far more than seven of them). When seen through binoculars, these stars appear shrouded in gas and dust, indicating that they are young and that new members are being formed as gravity causes the material to coalesce.

Beginning at the feet of Orion and winding its way to the southern horizon and thence into unknown realms is a string of relatively dim stars. This constellation is Eridanus, the river. It, like Cetus, the whale, contains a star that is thought by many scientists to have a solar system like ours. That star, known as Epsilon Eridani, has been the subject of science fiction stories for this reason.

Figure 2-29. Taurus, the bull, is just above Orion in the winter sky. Nearby are the Pleiades, a loose cluster of stars.

Quiz

QuizRefer to the text if necessary. A good score is 8 correct. Answers are in the back of the book.

1. As the seasons progress, the constellations appear to gradually turn counterclockwise around the north celestial pole from night to night because

(a) Bootes and Canes Venatici chase Ursa Major around Polaris.

(b) the sidereal day is slightly shorter than the solar day.

(c) Earth rotates on its axis.

(d) the galaxy spirals around its center.

2. If you live in the northern hemisphere, the elevation of Polaris above the horizon, in degrees, is about the same as

(a) your latitude.

(b) 90 degrees minus your latitude.

(c) the elevation of the Sun in the sky at noon.

(d) nothing in particular; its elevation changes as the seasons pass.

3. Tau Ceti is considered a special star because

(a) it revolves around Polaris in a perfect circle.

(b) it is inside our solar system.

(c) it is in a constellation all by itself.

(d) some astronomers think that it might have a solar system like ours.

4. Earth slowly wobbles on its axis, causing the constellations to

(a) change shape slightly from year to year.

(b) gradually converge on Polaris.

(c) shift position in the sky slightly from century to century.

(d) follow the plane of the ecliptic.

5. People in the time of Julius Caesar saw constellations whose individual shapes were

(a) the same as they are now.

(b) somewhat different than they are now.

(c) almost nothing like they are now.

(d) nothing at all like they are now.

6. The constellation Andromeda is well known because it contains

(a) the brightest star in the whole sky.

(b) all the planets at one time or another.

(c) the north celestial pole.

(d) a spectacular spiral galaxy.

7. Orion is a landmark constellation in the northern hemisphere

(a) all year round.

(b) during the winter.

(c) only north of about 45 degrees latitude.

(d) because it contains the brightest two stars in the sky.

8. Coma Berenices is sometimes mistaken for

(a) the sword of Orion.

(b) Ursa Major.

(c) the Andromeda galaxy.

(d) the Pleiades.

9. The pole star, Polaris, is part of

(a) Canis Major.

(b) Pegasus.

(c) Ursa Minor.

(d) no constellation; it stands by itself.

10. The stars Vega, Altair, and Deneb dominate the sky

(a) in the circumpolar region.

(b) during the northern hemisphere summer.

(c) during spring, summer, and fall, respectively.

(d) No! These are not stars but constellations.