7

Genetics

Rex Dunham

7.1 Introduction

Genetic intervention has been used to enhance animal and plant agriculture production for centuries and has intensified during the last two centuries. Aquaculture genetics has tremendous potential for enhancing aquaculture production and is now being applied to aquatic organisms to improve production traits. Modern research on Aquaculture Genetics began sporadically 80 years ago and became common place in the 1970s. During the last three decades, research in this area has steadily grown, and now research on traditional selective breeding, genetic biotechnology, transgenics and genomics is quite active. Modern techniques, such as marker‐assisted selection, are being researched, and there is broad application of genetic enhancement in aquaculture, including selection, multiple‐trait selection, marker‐assisted selection, interspecific hybridisation, polyploidy, genetic monosexing and recently genetic engineering

Twenty years ago, most marine fish production remained equivalent to the use of undomesticated ancestral cattle and chickens in ancient terrestrial agriculture; however, selection programs are now common place for some of the major species. Still, some reports indicate that genetic improvement programs in the aquacultuare industry are not widespread, and only 10% of commercial aquaculture populations are genetically improved (Gjedrem et al., 2012; Gjedrem and Robinson, 2014). This is true for genetic stocks used for new aquaculture species, which are essentially wild. However, these reports of lack of application of genetic enhancement programs only consider selection as genetic improvement. Obviously, there are alternative genetic enhancement programs, and after 40–50 years of genetics and breeding research, coupled with genetic biotechnology, established commercial species such as carps, catfish, salmonids, tilapias and oysters are essentially all genetically improved. The best available genotypes may have performance levels of up to 10‐fold that of poor performing wild genotypes, and the rate of progress and genetic gain certainly rivals that or exceeds that for terrestrial livestock. Regardless of the species and the genetic gain made as of today, much greater genetic progress can continue to be accomplished.

Effective programs have goals and plans, and this is also true for genetic enhancement programs. Goals are the important traits of economic importance that we want to improve, and the extent to which we consider it feasible to improve these traits. Genetic enhancement programs are then the plans that we use to accomplish these goals and objectives. The primary purpose of this chapter is to review these genetic enhancement programs to show how effective they have been with the focus on production traits of finfish, molluscs and crustaceans.

7.2 Basic Genetics

7.2.1 Gene Action

There are two basic types of gene action, dominance/recessive and additive.

In the case of dominance, only one copy of the dominant allele (A) in a diploid organism is needed for expression of the associated trait. In the case of the recessive allele (a), two copies of the allele are needed for the recessive phenotype to be observed:

- In a completely dominant system (Table 7.1a), a large unit of phenotypic change occurs when going from the homozygous recessive genotype (aa) to the heterozygous genotype (Aa) and no unit of change when going to the homozygous dominant genotype (AA).

- For additive gene action, the alleles act in an additive fashion with similar units of change when comparing the different genotypes (aa → Aa → AA) or as in mathematical addition, the stronger allele will make a greater contribution to the phenotype (Table 7.1e).

- In overdominance, the heterozygote is superior or outside the range of the phenotypes of the two parental homozygotes (Table 7.1c).

Table 7.1 Basic types of gene expression.

| Genotypes | Phenotypes | Unit of phenotypic change between genotypes | |

| (a) Complete dominance | bb Bb BB | red black black | ↕ large ↕none |

| (b) Incomplete dominance | bb Bb BB | white dark grey black | ↕large ↕small |

| (c) Overdominance | ss Ss SS | malaria prone healthy (best) sickle cell (sick) | ↕large ↕large |

| (d) Co‐dominance | AA Aa aa | black black and white white | large equal units of change |

| (e) Additive | rr Rr RR | white pink red | large equal units of change |

Further, in the case of alleles at more than one locus, the alleles at one locus can affect the expression of alleles at another locus. This type of gene interaction is termed epistasis.

7.2.2 Qualitative Traits

Qualitative traits are phenotypes that are expressed in an all or nothing fashion. For example, albino or normal colouration is usually a result of gene expression from a single or only a few loci. Colouration and deformities are examples of qualitative traits.

Qualitative traits such as changes in colour, finnage, scale pattern or deformities can be desirable or detrimental in aquaculture. Obviously, qualitative traits are important and the primary basis for the ornamental aquaculture industry. Deformities can be valuable in the ornamental trade, but are usually undesirable in the food trade industries. If these qualitative traits are a result of dominant gene action, they can be easily eliminated as all homozygous dominant and heterozygous (carrier individuals) phenotypes are obvious, and those individuals can be immediately selected against, resulting in a population with none of the dominant detrimental allele. An example of this is the saddleback mutation in tilapia. On the other hand, it is extremely difficult to eliminate a deleterious recessive allele from a population, since heterozygous carriers cannot be identified by simple visual observation (Table 1a). If the trait was of high economic importance or damage, the heterozygous carriers could be eliminated, by mating them with individuals of known genotype and examining the phenotypic ratios in the progeny: progeny testing. Since fish are highly fecund and produce large numbers of progeny, progeny testing could eliminate the deleterious allele from the population in a single generation.

When deformities are observed, fish culturists often assume that the deformities have a genetic basis and that they are likely to be increasing because of inbreeding in the population. However, these assumptions are often false. Many deformities observed are environmentally induced and are often related to low egg quality or poor water quality in the hatchery.

There are different types of dominance (Table 7.1), as discussed earlier. In the case of complete dominance, the trait is fully expressed in the heterozygous and homozygous dominant genotypes. Normal colouration (in contrast to albinism, which is homozygous recessive) and saddle back are examples of complete dominance in fish.

The heterozygous genotype allows a major, but not complete unit of change in the phenotype in incomplete dominance. The homozygous dominant genotype is necessary to make the complete maximum shift in the phenotype. In the case of overdominance, the phenotype of the heterozygous genotype is outside the range of the two homozygous genotypes (Table 7.1c). The phenotype associated with each allele is observed in the case of co‐dominance (Figure 7.1).

- Epistasis is the interaction of genes at different loci. Alleles at one locus can affect the expression of alleles at another locus. Epistasis is the basis of some colour types in fish. For instance, it is the explanation for some red and black colour variants in tilapia and scale pattern in the common carp is also influenced by epistatic gene action (Figures 7.2 and 16.5).

- Pleiotropy is when one gene affects more than one trait. The alleles and loci that affect scale pattern in common carp are an excellent example of this phenomenon. These genes not only affect scale pattern, but also growth, survival, other meristic traits, tolerance of low DO, haemoglobin and haematocrit and the ability to regenerate fins. Some mutations can also have semi‐lethal or lethal effects, resulting in reduced viability or death. Again, certain alleles affecting scale pattern in common carp have semi‐lethal or lethal effects and this applies to the alleles responsible for saddleback in tilapia.

- Heterosis is the increased or decreased function of any biological quality in hybrid offspring as heterosis can be positive or negative. In the case of genetic enhancement of performance traits in animals the terms heterosis and hybrid vigour are interchangeable. However, we suggest for fish genetic enhancement this be standardised to heterosis as in population genetics hybrid vigour refers to reproductive fitness and occurs when F1 produce more living offspring than the parental genotypes.

Figure 7.1 Co‐dominance – both alleles are expressed equally. DNA or protein banding patterns illustrate the concept.

Figure 7.2 Line scale pattern in common carp. Genes for scale pattern in common carp have epistatic interaction, pleiotropy and semi‐lethality.

Source: George Chernilevsky. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike license, CC BY‐SA 3.0.

7.2.3 Phenotypic Variation

Individual phenotypes, the appearance, characteristics and performance of individuals, are a result of three main components:

- the environment;

- the genotype;

- the interaction between the genotype and the environment.

Thus, phenotypic variation (Vp) is a result of genetic variation (Vg), environmental variation (Ve) and variation due to the genotype – environment interaction (Vge):

Genetic variation in populations has several potential components as well:

- additive genetic variation;

- dominance genetic variation;

- variation due to epistasis interaction;

- variation due to maternal heterosis.

The type of genetic variation has a bearing on the success of the genetic enhancement program being attempted. For selection to be successful, a trait must have significant heritability and the ratio of additive genetic variation to total phenotypic variation (narrow sense heritability) must be high. However, absolute quantities of additive genetic variation and phenotypic variation are of equal or greater importance. Dominance, epistasis and overdominance are the genetic basis of heterosis: the relative performance of crossbreeds and hybrids compared to their parents. Thus, significant dominance‐related variation must exist for crossbreeding and hybridisation programs to be successful.

7.3 Epigenetics

The expression of genes can be greatly affected by environmental factors. Thus, qualitative and quantitative genetic variation can be even more complicated than once believed. Epigenetics relates to changes in gene expression without alteration of the DNA sequence. The environment alters gene expression by ‘silencing’ genes or ‘waking them up’, hence epigenetic modification, which is associated with the epigenome, the overall pattern of activation of the genome. The influence of epigenetics was once thought to primarily affect embryonic stages of development, but it is now known that these epigenetic influences can accumulate over time and actually be more prevalent in adult stages. Although brought about by the environment, epigenetic changes can be transmitted to one or more generations. Thus, how a fish is cared for, fed, exposed to disease and other environmental factors can have long lasting effects in the individual that can be passed on to its progeny and even further generations.

There are multiple mechanisms for epigenetic gene silencing. The main epigenetic mechanisms for altering gene expression include DNA methylation, chromatin modifications (histones) and non‐coding RNAs. Methylation is the attachment of methyl groups to DNA sequences in a gene, specifically to cytosine when it is adjacent to guanine. The functioning of the epigenome is also related to histones, proteins that control access of genes for transcription, for which the abundance can again be environmentally influenced.

7.4 Domestication and Strain Evaluation

Use of established domestic strains that are best performing is the first step in a genetic improvement program and the mechanism to make the most rapid initial progress in genetic improvement. Domestic strains of fish usually have better performance in aquaculture settings than wild strains of fish. Strain variation is also important, since strain affects other genetic enhancement approaches, such as intraspecific crossbreeding, interspecific hybridisation, triploidy, sex control and genetic engineering.

When wild fish are moved to aquaculture or hatchery environments, they are exposed to a new set of selective pressures that will change gene frequencies. Thus, an organism better suited for the aquaculture environment begins to develop. This process, termed domestication, occurs even without directed selection by the fish culturist. Domestication effects can be observed in some fish within as few as one to two generations after removal from the natural environment (Dunham, 2011).

In channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) an increased growth rate of 3 to 6% per generation was observed due to domestication selection (Figure 7.3), and the oldest domesticated strain of channel catfish (107 yr), the Kansas strain, has one of the fastest growth rates of all strains of channel catfish.

Figure 7.3 Percent improvement for Kansas select channel catfish compared to Kansas random channel catfish after first, second, third and fourth generation of selection for increased body weight.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Rex Dunham.

Domesticated common carp in Hungary showed better growth and resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila than wild strains. Although most domesticated strains usually perform better in the aquaculture environment than wild strains, there have been some putative exceptions, such as wild Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus and rohu, Labeo rohita, which appeared to grow better in the aquaculture environment. However, the explanation for this anomaly appears to be related to a lack of maintenance of genetic quality and genetic degradation in the domesticated strains compared to these wild fish. Poor performance of some domestic tilapia is related to poor founding (parental) lines, random genetic drift, inbreeding and introgression with slower growing species, such as O. mossambicus, and slower growing strains such as Nile tilapia from Ghana (Table 7.2).

Table 7.2 Strain variation in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Comparison of Egypt, Ivory Coast and Ghana strains for some traits that are important for aquaculture.

| Trait | Best performing strains |

| Growth rate | Egypt, Ivory Coast |

| Reproduction | Ghana |

| Cold tolerance | Egypt |

| Seinabilitya | Egypt, Ghana |

avulnerability to be seined in harvesting.

Domestication of farmed shrimp was relatively slow compared to that of finfish because of:

- the use of wild broodstock and postlarvae;

- a lack of understanding of shrimp reproductive biology for domestication of the species;

- endemic disease challenges;

- laws restricting movements of shrimp and disease‐free certification;

- the relatively recent nature of shrimp aquaculture.

As is the case with fish, domesticated shrimp are more cost‐effective than wild strains for aquaculture application, but the reproductive performance of domesticated Penaeus monodon and brown tiger shrimp, P. esculentus, are similar to wild brood stock. There are likely to be environmental causes for this similarity rather than genetic.

Strains of fish show large amounts of variability for many different traits. There are strains of channel catfish and rainbow trout strains that differ in growth rate, disease resistance, body conformation, dressed carcass %, vulnerability to angling and seining, age of maturity, time of spawning, fecundity and egg size. Okamoto et al. (1993) reported that an infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV)‐resistant strain of rainbow trout showed 4.3% mortality compared with 96.1% in a highly sensitive strain. Other strains of some marine fish species vary for upper‐temperature tolerance, including loss of swimming equilibrium and disassociated caudal fin.

7.5 Selection

7.5.1 Selective Breeding

Individual or mass, family, combined and index selection are alternative selection programs with various advantages and disadvantages. Individual selection is simple, effective and requires the least resources. However, since no pedigree information is available, individual selection will eventually lead to inbreeding and inbreeding depression of performance. However, in relatively small populations, 20 pairs breeding per generation, this inbreeding will not occur until 5–6 generations have elapsed. In highly, fecund species such as Chinese and Indian carps for which only a few spawns are required to meet hatchery needs, mass selection will lead to rapid inbreeding depression.

Family selection should lead to more rapid genetic gain. It allows genetic gain for lower heritability traits and prevents inbreeding since pedigrees must be maintained. Family selection also allows selection of both sexes for sex‐limited traits and selection for traits that require sacrifice of the fish such as carcass yield. The primary disadvantage to family selection is the extra resources and record keeping required to conduct this program. Combined selection includes individual selection within families, and theoretically, results in the most rapid genetic improvement via selection.

Research on selection in fish for relevant aquaculture traits began in the 1920s (Embody and Hayford, 1925), but very little selection was conducted prior to 1970. Unfortunately, during this period, several potentially high impact experiments did not include adequate genetic controls to prove genetic gain. From 1970 to the present, research on selection and traditional selective breeding has continued to grow rapidly (Dunham, 2011; Gjedrem et al., 2012; Gjedrem and Robinson, 2014) despite the excitement about and increased funding in the area of molecular genetics and genomics. In general, the response to selection for growth rate in aquatic species is very good compared to that with terrestrial farm animals and these programs have been highly successful (Table 7.3). Fish, shrimp and bivalve molluscs often have higher genetic variance compared to farmed land animals: genetic variation for growth rate is 7–10% in farmed terrestrial animals and 20–35% in fish, shrimp and bivalves. Fecundity is also higher in aquaculture species compared to warm‐blooded agriculture animals allowing for higher selection intensity for aquaculture production improvement, and a few hundred heritability estimates have been obtained for several traits of cultured fish and shellfish (Tave, 1993).

Table 7.3 Examples of improvements from selective breeding in aquaculture species.

| Species | Parameter | Number of generations of selection | % improvement |

| Rainbow trout | Body weight | 6 | 30 |

| Coho salmon | Growth rate | 10 | 50 |

| Atlantic salmon | Growth rate | 1 | 7 |

| Channel catfish | Growth rate | 4 | 55 |

| Brook trout | Resistance to bacterial furunculosis | 3 | 2% to 69% survival |

| Rainbow trout | Resistance to Flavobacterium psychrophilum | 1 | 32 |

| Common carp Vietnamese | Body weight | 6 | 5 per generation |

| GIFT Nile tilapia | Body weight | 8–14 | 11–13 per generation |

| Bivalve molluscs | Growth rate | 1 | 8–9 |

| White‐leg shrimp | Growth rate | 1 | 4.4 |

| White‐leg shrimp | Resistance to Taura virus | 1 | 12.4% survival |

Selection for increased body weight has a high probability of success in the vast majority of aquatic organisms and in the vast majority of strains within a species. Six generations of selection increased body weight by 30% in rainbow trout. An increase of 7% was achieved within a single generation in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and an increased growth rate of 50% was achieved with 10 generations in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Body weight was improved in channel catfish, by 12–20% with one to two generations of genetic selection, and the best line grew twice as fast as typical non‐selected strains. After three generations, the growth rate of channel catfish in ponds was improved by 20–30% and this was further increased to 55% after four generations of selection in a Kansas strain of channel catfish (Figure 7.3).

Selection for body weight has also been successful in marine species. Selection for body weight was successful in gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Selection improved growth of the marine shrimp, Marsupenaeus japonicas. Improvement in the growth, survival and total yields were obtained in two selected lines (10‐15 % increase in mean yields).

Selection is an effective genetic enhancement program to improve growth rates in bivalves and crustaceans. One generation of mass selection for growth rate in Pacific oysters increased growth rate by 8%, and mass selection of adult oysters gave a strong response to selection for growth rate in Crassostrea virginica. In other experiments, a 10–20% gain in growth rate of oysters was achieved after one generation of selection. A genetic gain of 9% increased growth rate in Sydney rock oysters (Saccostrea lomerate) was achieved in a generation and in the Chilean oyster (Ostrea chilensis). A 9% per generation of selection for growth rate has been estimated for the hard‐shell clam or quahaug (Mercenaria mercenaria). Selection for increased body weight has been successful for a variety of marine shrimp, freshwater prawns and crayfish (Gjedrem et al., 2012). Rate of genetic improvement in bivalves and crustaceans appears to be similar to that of finfish.

Selection has been effective for improving disease resistance, but not as consistently as selection for body weight. Strain variation for selection response is more prevalent for disease resistance than for body weight, and often no selection response is found for some strains while others will show significant enhancement of disease resistance as a result of selection. In the case of salmonids, selection for disease resistance has been particularly successful (Embody and Hayford, 1925). Three generations of selection for resistance to endemic bacterial furunculosis in brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) improved survival from 2% to 69%. Resistance to furunculosis in brown trout (Figure 7.4) and brook trout has been improved via selection. One generation of selection increased resistance to Flavobacterium psychrophilum (bacterial cold‐water disease) in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) by an absolute 32% and a relative 105%. Selection response for resistance to viral and bacterial diseases in salmonids has sometimes been as much as 18–19%.

Figure 7.4 Brown trout, Salmo trutta.

Source: USFWS. Photograph by Eric Engbretson http://www.underwaterfishphotos.com

Selection for increased disease resistance and survival has also been successful in crustaceans and bivalves. A response for one generation of selection of 4.4% for growth rate and 12.4% for survival was obtained in the white‐leg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, when exposed to Taura syndrome virus. More dramatically, resistance to Taura syndrome virus had an absolute 30% improvement and a relative improvement of 100% with two generations of selection in L. vannamei. Additionally, growth and pond survival were improved 5–6% per generation.

Heritability1, additive genetic variation and selection response can vary among strains for body weight, and tilapia and common carp (Cyprinus carpio) are several of the more prominent examples of this phenomenon. Body weight of common carp initially appeared unresponsive to selection as five generations of selection for increased body weight resulted in no genetic gain, and five generations of family selection resulted in modest gains of about 5–10%. However, in a Czechoslovakian strain of common carp heritabilities for body weight were estimated at 0.15–0.49. Vietnamese common carp had a heritability of 0.3 for growth rate, and six generations of selection increased body weight by 5% per generation.

Mass selection has improved body weight in the Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus), red tilapia, Nile tilapia (O. niloticus), O. shiranus and, blue tilapia (O. aureus). However, selection for increased body weight in red tilapia has been variable. Even greater variability to the selection response has been observed in Nile tilapia: from no response in some strains, 1–7% gain per generation in others and as much as 11% per generation in the Philippines for the GIFT strain. The lack of response in some strains may reflect a narrow genetic base in the founder stock or sole use of mass selection in cases where additive genetic variation was low. Some selection programs for Nile tilapia were moderately successful, 14% body weight increase over two generations for a synthetic Egyptian strain. Selection for increased growth in GIFT Nile tilapia was much more productive, with 77% to 123% growth improvement after 7 generations of selection. During the first two generations of selection, similar responses to selection in Nile tilapia grown in low input environments as were found in the first two generations in the GIFT population, which was selected in a variety of environments. The 11% genetic gain per generation in GIFT tilapia was better than that obtained in most other species of fish, which typically average 5–7 % per generation as demonstrated for salmonids following approximately 10 generations of selection. However, other exceptional examples exist such as that for channel catfish, which had an increased body weight of 14 % per generation over four generations, and the 13–14 % increase per generation observed in some cases for salmon.

Response to selection can differ depending on the direction of selection. Body weight of common carp in Israel was not improved over five generations but could be decreased in the same strain selected for small body size. Virtually identical results for Nile tilapia have also been reported. In general, it is easier to select to make traits smaller rather than larger, which, of course, would rarely have aquaculture significance. There are exceptions to the above observations above as common carp in the Czech Republic responded to selection for increased body weight, but not for decreased body weight.

Body conformation can be dramatically changed via selection. Heritability for body depth is quite high in common carp. Recently, a significant heritability was found for deformities in the Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua. The implication is that deformity rate could be reduced through selection.

Reproductive traits tend to have high selection responses. Spawning date can be shifted in coho salmon, Oncorhynchus kisutch, by about 14 days with four generations of selection. Age at sexual maturation, fecundity and even sex ratio are heritable traits in fish. Strong genotype‐environment interactions for sex determination can exist for fish. Heritability for gender and sex ratio can be dramatically different at different hatching and rearing temperatures, allowing for selection for highly skewed sex ratios or monosex populations.

Long‐term selection appears feasible in fish. Nile tilapia body weight was doubled through seven generations of selection. The 8th to 14th generations of selection for body weight in GIFT Nile tilapia resulted in a response per generation of 13 % even after this length of time.

7.5.2 Correlated Responses to Selection and Indirect Selection

When selection is conducted upon one trait, positive, negative or no correlated responses to selection can occur for other traits depending upon the nature of genetic correlations among traits (Table 7.4). Additionally, in mass selection programs there is the potential for decrease in performance in some traits, long‐term, because of the accumulation of inbreeding.

Table 7.4 Examples of correlated responses to selection.

| Correlated traits | ||||

| Species | Trait selected | Positive | No correlation | Negative |

| Channel catfish | Increased body weight | dress‐out %a feed consumption FCEb | body composition seinabilityc | low DO tolerance |

| Atlantic salmon | Growth rate | feed consumption FCE | ||

| European whitefish | Growth rate | FCE | ||

| Rainbow trout | Muscle lipid content | dress‐out % fillet % | ||

| Rainbow trout | bacterial cold‐water disease resistance | body weight thermal growth coefficients | ||

a (body weight without head, viscera and skin) × 100 /total body weight.

b FCE (food conversion efficiency) (%) = 100/FCR.

c vulnerability to be seined in harvesting.

Genetic correlations, if positive, among traits allow for the possibility of indirect selection, selecting a second trait to improve the primary trait of interest. Under certain conditions indirect selection can be more effective than direct selection. Additionally, indirect selection has some of the advantages of family selection as it can allow selection of sex‐limited traits and lethal traits.

Although selection for body weight has generally been associated with positive correlated responses such as increased survival and disease resistance, in some cases long‐term selection results in decreased bacterial resistance either due to changes in genetic correlations or due to inbreeding depression. Increased fecundity, fry survival and disease resistance were correlated with selection for increased body weight in channel catfish after one generation of selection for body weight. Three and four more generations of selection resulted in increased dress‐out percentage2, decreased tolerance of low DO and no change in body composition or seinability3. Progeny from select channel catfish had greater feed consumption, more efficient feed conversion and greater disease resistance than controls.

Atlantic salmon show a positive correlated response in feed conversion when selected for growth rate. Wild salmon had a 17% higher intake of energy and protein per kg of growth compared with fish from the 4th generation selected for growth rate. The wild fish had eight percent lower retention of both energy and protein. There are strong genetic correlations between growth rate and feed conversion in European whitefish, Coregonus lavaretus, and channel catfish, and the nature of the heritabilities and genetic correlations indicate that indirect selection for feed conversion by selecting for growth rate would more effectively improve feed conversion than direct selection for feed conversion efficiency.

The relationship between body weight and carcass traits is not consistent from one species to another. The nature of the heritabilities and genetic correlations among body weight, visceral fat, muscular fat, muscular moisture and muscular ash in gilthead seabream, Sparus auratus, would allow development of a selection index to improve growth, fat content, texture and carcass yield simultaneously. Dress‐out and fillet % also had positive heritabilities in gilthead seabream. However, % body weight and % fillet had a negative genetic correlation indicating that it might be difficult to simultaneously select for both traits. In the case of sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, body weight, % viscera, % visceral fat, % fillet and % head weight all had significant heritability. Body weight had a positive correlation with each of these traits except a negative correlation to % head weight, indicating selection for increased body weight would also increase % fillet, but result in fish with a higher % visceral fat. Body weight, % fat, relative head length, relative body height, relative body width, % processed body and fillet yields had moderate to high heritabilities in common carp in the Czech Republic. Body weight was highly correlated with % fat. Relative head length had strong negative correlation with % fat, % dress‐out and % fillet. Thus, indirect selection for reduced relative head length should increase % fillet, and % dress out, but also increase % fat. Selection for increase body weight would also result in a fattier common carp.

Muscle lipid content in rainbow trout responded to bi‐directional selection. Selection for muscle lipid content did not impact dress‐out % or fillet %.

A variety of genetic relationships exist among growth and survival traits. Selecting for resistance to bacterial cold‐water disease in rainbow trout did not affect body weight or thermal growth coefficients. Resistance to furunculosis, infectious salmon anaemia and infectious pancreatic necrosis all had relatively high heritabilities in Atlantic salmon. Additionally, the genetic correlations among these traits were all zero, which should allow simultaneous selection for all three traits without any negative correlated responses to selection.

Heritability for upper thermal tolerance is significant in rainbow trout. Genetic correlation between this trait and body weight was essentially zero, thus no correlated responses on the corresponding trait would be expected when selecting for either of these traits. Melanin deposits of Atlantic salmon were negatively correlated with pericarditis, pericarditis was not correlated with body weight; however, pericardial fat was correlated with body weight. Shell closing strength has a high heritability in Japanese pearl oysters, Pinctada fucata. This trait is correlated with high summer survival as the ability to close the shell tightly appears to be a major survival trait.

7.5.3 Multiple‐trait Selection

More than one trait can be selected at a time. Various techniques can be applied, but the most common and effective is multiple‐trait selection using a selection index. Each trait is weighted with regression coefficients that are generated from the heritability, genetic correlation, phenotypic correlation and economic value. Little multiple‐trait selection has been conducted in aquaculture because of the extra effort and record keeping required. However, this technique has great potential in aquatic organisms compared to terrestrial animals as the high fecundity of fish, crustaceans and bivalves allow more intense multiple‐trait selection.

Multiple‐trait selection was not successful in white‐leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) for growth and resistance to Taura virus syndrome as these two traits were negatively correlated (Argue et al., 2002). Simultaneous selection for body weight and fillet percentage improved both traits in Nile tilapia.

7.5.4 Marker‐assisted Selection and Genomic Selection

Aquaculture genomics has generated an explosion of information during the past 22 years. Framework linkage maps have been constructed with large numbers of markers, particularly type I markers of known genes, have been generated for a number of aquaculture species. Normalised cDNA libraries for EST analysis and functional analysis have been constructed. Functional genomics has advanced rapidly and the knowledge of gene expression responsible for growth, disease resistance, reproduction, sex ratio and response to cold temperature and other traits has been greatly expanded for aquaculture species utilising tools such as EST (expressed sequence tag) analysis and microarrays. Radiation hybrid panels in tilapia and analysis of BAC (bacterial artificial chromosome) libraries in catfish has greatly advanced the area of physical mapping of fish genomes. For some aquaculture species such as catfish and salmon, the majority of the genes have been isolated and cloned. Catfish have about 27 000 genes of which currently around 50% are of known function. Sequencing of fish genomes is well advanced for some aquaculture species and is nearing completion in some cases. This progress in the past 22 years is quite remarkable.

Quantitative trait loci, QTL, analysis generates the data to allow marker‐assisted selection, MAS; selection based on genetic markers associated with a quantitative trait. A great deal of QTL mapping and analysis has been conducted for aquatic organisms, but very little MAS because of the added expense and need for both greater resources and record keeping compared to traditional selection. Marker‐assisted selection programs have been successfully evaluated in various animal and plant systems. Much theoretical research has been conducted which indicates that marker‐assisted selection has the potential to greatly accelerate genetic improvement in breeding programs. Initial experiments with corn, tomatoes, barley, pigs and dairy cattle have all given positive results indicating that the utilisation of DNA and protein markers has the potential to accelerate genetic improvement in various crops or terrestrial animals.

However, marker‐assisted selection is not always the most efficient or cost‐effective method. These initial experiments indicate that when heritability for a trait is high, marker‐assisted selection does not provide any faster rate of genetic gain than traditional selection. However, when heritability is low, the rate of genetic gain obtained from marker‐assisted selection can be substantially higher than that for traditional selection. Another disadvantage of MAS is that the genetic markers are usually strain specific, preventing the use of the background research across strains and populations.

QTL markers for growth, feed‐conversion efficiency, tolerance of bacterial disease, spawning time, embryonic developmental rates and cold tolerance have been identified in channel catfish, rainbow trout and tilapias. Putative linked markers to the traits of feed‐conversion efficiency and growth rate have been identified for channel catfish (Dunham, 2011). In trout and salmon, a candidate DNA marker linked to infectious haematopoietic necrosis (IHN) disease resistance has also been identified and for IPN disease in Atlantic salmon. A single IPN QTL found on LG1 accounts for most of the variation in IPN resistance and a highly resistant line can be developed by selecting this marker. QTL maps have been developed that have multiple markers for bacterial disease resistance in Japanese flounder as well as for body weight, total length and a variety of body conformation traits in channel catfish and body weight in Asia seabass, Lates calcarifer. A SNP for RuvB‐like protein in Giant Tiger shrimp is associated with fast growth rate.

Marker‐assisted selection has not been broadly applied in fish. However, MAS lead to the development of a line of lymphocystis disease resistant Japanese flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus. These fish were widely applied on farms and demonstrated high levels of disease resistance and survival. MAS may be a mechanism to improve the efficiency of monosex male production in Nile tilapia. A microsatellite marker has been found on linkage group 23 that is associated with sex determination. MAS improved feed‐conversion efficiency by 11% for aquaculture species, while traditional selection improved feed‐conversion efficiency by 4.3%. The growth rate of rainbow trout was increased by 26% based on selection for an mtDNA marker, but this method was strain‐specific because the relative performance of fish with the specific haplotype was consistent across males within strains but not across strains. In contrast, six generations of traditional selection were required to increase body weight by 30% in rainbow trout. In rainbow trout, 25% of progeny showed a high degree of upper‐temperature tolerance after MAS for heat tolerance.

Genomic selection is on the cusp of revolutionising selective breeding, and, theoretically, new schemes based on whole genome selection may enhance rate of genetic gain even for traits with high heritability. In this case, genome wide association studies, GWAS, generate the data on the impact of every single nucleotide polymorphism, SNP, on performance of all traits. These studies are just beginning in aquatic organisms. The SNPs can be strain specific, but many are species wide. The newness of the technology, the expense, the need for high‐powered bioinformatics analysis and record keeping have prevented rapid generation of GWAS results in aquatic organisms followed by genomic selection. Genomic selection is increasingly being used in livestock selective breeding and genetic enhancement. Initial experiments indicate that genome selection should produce more rapid genetic gain for bacterial cold‐water disease resistance than traditional selection in rainbow trout (Vallejo et al., 2016).

7.6 Inbreeding and Maintenance of Genetic Quality

Even if genetic enhancement is not a goal, loss of genetic quality and avoiding reduction in performance will always be a goal. It is as important to prevent production losses due to inbreeding as it is to increase production from genetic enhancement. This is especially true for species with high fecundity, such as carps, where few brood stock at a single hatchery are necessary to meet demands for fry and brood stock replacement. The detrimental effects of inbreeding, the mating of related individuals, are well documented and can result in decreases of 30% or greater in growth production, survival and reproduction (Dunham, 2011) once the inbreeding coefficients reach 0.125 and 0.250 (percent increase in loci homozygous due to the mating of relatives). For many traits, as the inbreeding increases, the extent of the inbreeding depression also increases. Inbreeding depression is easily correctible. When an inbred individual is mated to an unrelated individual, the inbreeding coefficient of the progeny returns to 0.0 and the effects of inbreeding on the performance of the progeny are also eliminated and inbreeding depression is also zero. This was demonstrated in channel catfish. In most aquaculture businesses inbreeding will not become a problem because brood stock populations are relatively large. If 50 breeding pairs are randomly mated per generation, the accumulated inbreeding should not result in inbreeding depression for 25–50 generations. Formulas for calculating inbreeding and determining the impact of random genetic drift are thoroughly discussed in Tave (1993).

7.7 Crossbreeding and Hybridisation

7.7.1 Intraspecific Crossbreeding

The opposite of inbreeding, crossbreeding is the mating of unrelated individuals. Intraspecific crossbreeding (crossing of different strains, lines, breeds or races) has the potential to increase growth rate and other traits, but heterosis (differences between offspring and parents) may not be obtained in every case. However, intraspecific crossbreeding is a relatively effective genetic enhancement program to improve growth rate, and tends to be highly effective for improving survival‐related traits and reproductive performance. This excellent genetic enhancement program is probably underutilised because:

- it does not have international advocates like selection;

- requires some effort to identify strains that combine well; and then

- requires maintenance of two or more strains without mixing and genetic contamination.

Approximately 55% and 22% of channel catfish and rainbow trout crossbreeds evaluated, respectively, elicited improved growth rate (Dunham, 2011). Chum salmon crossbreeds, however, had no heterotic increases in growth rate (Dunham, 2011). Common carp crossbreeds generally express low levels of heterosis and only about 5% of the crossed carp that were evaluated had enhanced growth rates. However, those that showed positive heterosis are quite important and at one time were the basis for carp aquaculture in Israel, Vietnam, China and Hungary.

In the case of channel catfish, reciprocal crosses did not perform the same and there appeared to be a maternal effect on combining ability.

The crossing of common carp lines in Hungary demonstrates the frequency of success in long‐term crossbreeding for this species. During a 35‐yr period, more than 140 crosses were tested. Three were chosen for culture, based on ca. 20% improvement in growth rate and other qualitative features, compared to parent and control carp lines. Approximately, 80% of common carp production in Hungary is generated from these Szarvas crossbreeds. In Israel, the crossbreeding of the common carp strain, DOR‐70 and the Croatian line, Nawice, resulted in fast growth and was widely utilised on Israeli farms. The Czech Republic also utilises improved growing crossbreeds, South Bohemian × Northern mirror carp and Hungarian 15 × Northern mirror (Figures 7.2 and 16.5). In Vietnam, crossbreeding of eight local varieties of common carp, along with Hungary, Ukraine, Indonesia and Czech strains resulted in significant heterosis in the F1 progeny. The Vietnamese × Hungarian common carp crossbreed was particularly popular, due to fast growth and high survival rates under different production conditions. Double crosses among Vietnamese, Hungarian and Indonesian strains have subsequently been used for carp selection and crossbreeding ceased throughout Vietnam because farmers had difficulty maintaining pure parental lines for the crossbreeding.

Heterosis for growth rate, body shape, fillet yield and % visceral body fat has been observed in Nile tilapia. In the case of the silver barb, Barbodes gonionotus, 23–35% higher growth rate was found in crossbreeds than the parent strains. Crossbreeds of different strains of European catfish, Silurus glanis, have outstanding adaptability under warmwater holding conditions and mixed diet feeding regimes. Crossbreeding can also improve performance in crustaceans and resulted in heterosis for growth rate, but not survival in Chinese white shrimp (Fennropenaeus chinensis).

Crossbreeding often improves survival traits. Strains of cold‐resistant carp, Ropsha carp, for cold zones in northern Russia have been developed by crossing local carps and Siberian wild carps from the River Amur. Wild strains of common carp are less susceptible to koi herpes virus (= carp interstitial nephritis and gill necrosis virus), whereas, domestic strains tend to be vulnerable. Two domestic strains, two domestic × wild crossbreeds and one domestic × domestic crossbreed were compared for viral resistance. In the laboratory, the most resistant genotype was one of the domestic × wild crossbreeds and one of the pure strains was the least resistant. The remaining genetic groups were intermediate in viral resistance. When the challenges were repeated in ponds, the results were the same except the other domestic × wild crossbreed had excellent resistance in ponds, although its performance had been intermediate in the laboratory.

Crossbreeding of the walking catfish, Clarias macrocephalus, improves resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila infections. Crossbreeding improved phagocytosis activity in African catfish, Clarias gariepinus, but did not enhance body weight, total length, the specific immune response to A. hydrophila, phagocytic index or male reproductive performance. In the case of channel catfish, reciprocal crosses did not perform the same and there appeared to be a maternal effect on combining ability.

Domestication has a strong influence on the success of crossbreeding programs. Domestic × domestic crosses are more likely to result in heterosis than wild × domestic and wild × wild crosses for several traits. Domestic × domestic channel catfish (Table 7.5) and rainbow trout are more likely to show heterotic growth rates than domestic × wild crossbreeds.

Table 7.5 Number of channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) from domestic (D) by domestic (D × D) crosses and domestic × wild (W) (D × W) crosses showing positive, negative or no heterosis (hybrid vigour) for growth rate.

| Heterosis | |||

| Cross | Positive | None | Negative |

| D × D | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| D × W | 2 | 3 | 1 |

Again, crossbreeding does not always result in genetic improvement. No heterosis was observed for reciprocal crossbreeds between a domestic and wild strain of Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, for growth survival, saltwater growth, saltwater tolerance, stress response and recovery and fecundity. Crossbreeds between wild and domestic Atlantic salmon were intermediate in performance for body weight, condition factor and sexual maturation. When wild strains of European sea bass, Dicentrarchus labrax, were crossed, large strain differences were obtained for survival, growth, shape, sex ratio, muscular fat content, visceral yield and spinal deformities, but not fillet yield. There was no heterosis among these wild strains and no GXE interactions. This helps illustrate the fact that heterosis is less likely to be obtained from wild strains than for domestic strains.

Apparently, domestication also affects the success of crossbreeding in crustaceans as well. When two wild strains of giant freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii, were crossed with a domestic strain (Bangkok), large additive strain effects were observed for growth, but no heterosis. Wild strains were involved and little heterosis observed. The domestic strain was the fastest growing of the strains. The most rapidly growing prawns were some of the crossbreeds. Reciprocal crossbreeds did not have the same performance.

One crossbreeding practice is to develop inbred lines to use in crossbreeding programs to obtain heterosis. The existing data indicate that it is unlikely to obtain true genetic gain using this strategy. The crossbreeding of inbred lines of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas, often resulted in heterosis for growth and survival. Additionally, crossing of inbred lines of Pacific oysters reduces summer mortality. Similarly, the crossing of two inbred lines of cockle, Fulvia mutica, resulted in increased shell length and whole body weight, but intermediate survival. It is likely that this is not true genetic enhancement. It has been demonstrated that inbreeding reduces growth in channel catfish. Crosses of the inbred lines did indeed grow faster than the parental inbred lines. However, the performance of the crossbreeds only negated the inbreeding depression and was equivalent to that of the original population, so no true genetic gain was obtained as performance returned to the original baseline. Production of gynogenetic female lines and gynogenetic sex‐reversed inbred male lines from common carp with the best combining ability was an important part of the Hungarian crossbreeding programs. A higher heterosis was expected from crossing inbred lines, but the growth rate of F1 crossbreeds was only 10% higher than controls.

One small potential impediment to crossbreeding programs is seed production. Strain mating incompatibility, can occur and impede fry output in channel catfish and Nile tilapia, and this appears to be more strongly influenced by the female than the male.

7.7.2 Interspecific Hybridisation

In principle and in genetic basis, interspecific hybridisation is similar to intraspecific crossbreeding. This has been a popular breeding program as over the years fisheries biologists have repeatedly tried to combine the best traits of more than one species, mostly with little success. Interspecific hybridisation rarely results in heterosis. However, interspecific hybridisation sometimes resulted in fish with increased growth rate (Figure 7.5), manipulated sex ratios, sterilised animals, improved flesh quality, increased disease resistance, improved tolerance of environmental extremes, and other altered traits.

Figure 7.5 Length – frequency distribution of age1+ (1989 class) of black crappies (BC) (Pomoxis nigromaculata) and white crappies (WC) (P. annularis) and hybrids (F1) collected in autumn (fall) 1990. The dotted lines indicate the minimum size for fishing.

Source: Travnichek et al. 1996. Reproduced with permission from Taylor & Francis.

Although interspecific hybridisation rarely results in an F1 suitable for aquaculture application, there are a few important exceptions to this rule. The channel catfish female × blue catfish, Ictalurus furcatus, male is the only hybrid of nearly 50 North American catfish hybrids examined that shows superiority for growth rate, growth uniformity, disease resistance, tolerance of low DO levels, dress‐out% and harvestability. This is by far the best genotype for ictalurid farming. This is now the best example of commercialisation of interspecific hybrids as 70% of US catfish production is now hybrids. Also, this is the best example of overall genetic enhancement in aquaculture.

Although they do not show heterosis for such a broad spectrum of traits, crosses of the silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), black crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus) and P. annularis and African catfish hybrids (Clarias gariepinus, Heterobranchus longifilis and H. bisorsalis) all show faster growth than parent species. In marine fish, the family Sparidae, hybrids of P. major and common dentex, Dentex dentex, also grow faster than parental genotypes.

In the case of shellfish, various hybrids between the Thai oyster species (Crassostrea belcheri, C. lugubris and Saccostrea cucullata) were compared, but no heterosis was observed. However, heterotic pearl production has been achieved in China using interspecific hybridisation. The hybrid between the freshwater pearl mussels, Hyriopsis schlegel ♀ and H. cumingii ♂, increased pearl size by 23%, pearl output by 32% and the frequency of large pearls by 3.7 times.

Heterosis for a single trait is not necessarily essential for an F1 hybrid or cross to have increased value compared to the parents. The composite performance may make the F1 the culture genotype of choice. The ‘sunshine’ bass between white bass, Morone chrysops and striped bass, M. saxatilis, grows faster, with better overall culture characteristics for growth, good osmoregulation, high thermal tolerance, resistance to stress and certain diseases, high survival under intense culture, ability to use soybean protein in feed, handling tolerance and angling vulnerability than either parent species. Other examples of crosses that have resulted in improved overall performance in experimental aquaculture conditions include:

- common carp with rohu;

- mrigal (Cirrhinus irrhosis) and catla (Catla catla);

- tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum) and the pacus, Piaractus brachypoma and P. mesopotamicus;

- green sunfish (Lepomis cyanellus) crossed with bluegill (L. macrochirus);

- gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) with red seabream (Pagrus major).

One of the best examples of commercial application of interspecific hybridisation is that for walking catfish. At one time the primary catfish cultured in Thailand was the hybrid between African (Clarias gariepinus) and Thai (C. macrocephalus) catfish. Although it does not grow as fast as pure African catfish, it grows faster than the Thai walking catfish and its yellow flesh is acceptable to Thai consumers in contrast to the red flesh of the African walking catfish. However, consumer and social attitudes influence breeding goals. The younger generation of Thai accept red flesh, making the African walking catfish the preferred culture genotype. Another example of a good ‘compromise’ hybrid is the rohu (Labeo rohita) x catla (Catla catla) hybrid which grows almost as fast as pure catla, but has the small head of the rohu considered desirable in Indian aquaculture. Catla catla × Labeo fimbriatus (fringe‐lipped peninsula carp) hybrids have the small heads of L. fimbriatus, plus the deep body and growth rate of catla.

Another potential benefit of interspecific hybridisation is that some species combinations result in progeny with skewed sex ratios or monosex progeny. Monosex populations of fish are desirable when growth differences between the sexes, sex‐specific products such as caviar are wanted, reproduction needs to be controlled or when other exploitable sexual dimorphism exists. Hybridisation in tilapias or centrarchids often result in near monosex hybrids. Hybridisation between the Nile tilapia and the blue tilapia, Oreochromis aureus, results in predominantly male offspring. Tilapia matings, which produce mainly male offspring, include Nile tilapia × O. urolepis honorum or O. macrochir, and O. mossambicus × O. urolepis honorum. Conversely, the hybrid between striped bass and yellow bass (M. mississipiensis) produces 100% female individuals.

Theoretically, the production of sterile hybrids can reduce unwanted reproduction or improve growth rate by energy diversion from gametogenesis or reduction in sexual behaviour. Karyotype analysis is believed to be a general predictor of potential hybrid fertility. Hybrids of Indian major carps are generally fertile because they share similar chromosome numbers (2 N = 50). However, when they are mated with common carp (2 N = 102), the hybrids have what is equivalent to a 3 N chromosome number and they are sterile. A natural triploid also occurs when crossing between grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idellus and bighead carp. Grass carp are commonly utilised for aquatic macrophyte control in the US, but there is concern about them establishing in the natural environment, resulting in potential impact on desirable vegetation in the ecosystem. The grass carp – bighead carp is not a viable option for weed control as, although this triploid hybrid has reduced fertility, some progeny maintain diploidy and could be fertile. An exception to the chromosome number‐fertility rule includes some crosses of sturgeon species with different chromosome numbers that produce fertile F1 offspring.

Hybridisation is a good program to improve disease resistance in fish such as is the case for coho salmon, (Oncorhynchus kisutch) hybrids, which are considered resistant to several salmonid viruses. However, overall viability was poor. Viability increased when hybridisation was followed by creating triploids. In some cases, the salmon hybrids showed the outstanding viral resistance, but very poor growth. Triploid Pacific salmon hybrids sometimes show earlier seawater acclimation. Similarly, increased tolerance of various environmental factors may also be inherited by F1 hybrids when one parent species has a wide or specific physiological tolerance. Several tilapia hybrids display enhanced salinity tolerance. Florida red‐strain hybrids (O. mossambicus × O. urolepis hornorum) can reproduce in salinities as high as 19‰, which is not necessarily a good trait when considering the potential environmental impact.

Just as was the case for intraspecific reciprocal F1 crossbreeds, reciprocal F1 interspecific hybrids usually show different phenotypes and performance. Reciprocal hybrids of O. niloticus (N) × O. mossambicus (M) demonstrate different salinity tolerances. Genetic maternal effects were evident as the hybrid with the O. niloticus mother had a higher survival rate after salinity challenges at 20‰ than pure O. niloticus, but lower survival rates than those of the reciprocal hybrid. At 30‰ salinity, a direct transfer killed all tilapia with O. niloticus maternal ancestry. Growth rates of N × M hybrids were comparable to those of Nile tilapia, while those of the M × N hybrids and O. mossambicus were comparable, but lower, than the first two groups, an additional example of maternal genetic effects.

Backcrosses, MN × N, also showed the highest salinity tolerance (comparable to that of O. mossambicus), but no significant differences in salinity tolerances were found in the remaining backcross (N × NM, NM × N, N × MN) or pure O. niloticus; thus some type of maternal effect from the maternal nuclear genome, cytoplasm or mitochondrial genome continued to be transmitted to the backcross generation. Carcass yield of the backcross hybrids, however, tended to be higher than those of the parent species. Interspecific backcrossing has also been used to successfully introgress genes for cold tolerance and colour among closely related tilapia (Table 7.6).

Table 7.6 Cumulative mortality from cold exposure for Oreochromis aureus (AA), red backcross O. aureus (AR), Oreochromis niloticus (NN) and red backcross O. niloticus (RN) illustrating the correlated performance of the red backcross and its associated backcross parent species.

| Cumulative mortality (%) | |||||

| Time | Genotypes | AA | AR | NN | RN |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 17 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 80 | |

| 3 | 7 | 10 | 100 | 100 | |

| 4 | 27 | 37 | 100 | 100 | |

| 5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

Hybridisation among marine species, and among marine and freshwater spawning species, has not shown much promise for developing improved fish for aquaculture application. Reciprocal hybrids between Sparus aurata and Pagrus major developed vestigial gonads at two to three years and were sterile, and no growth or survival superiority was observed compared to the parent species until sexual maturity. Hybridisation between European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) females and striped bass (Morone saxatilis) resulted in viable fry. Only triploid fry survived to 6 mo of age and at 8 mo the survivors showed poor growth compared to diploid D. labrax. Such hybrids would only be of commercial value where reproductive confinement is needed for ecological reasons and a highly desirable flesh quality was obtained.

7.8 Chromosomal Techniques

7.8.1 Gynogenesis, Androgenesis and Cloning

Gynogenesis, and androgenesis are techniques to produce rapid inbreeding and cloned populations. Gynogenetic individuals (‘gynogens’) produced during meiosis (‘meiotic gynogens’) are by definition ‘inbred’, since all genetic information is maternal. ‘Meiotic gynogens’ are not homozygous, since cross‐overs and recombination during oogenesis produce different gene combinations on the chromosomes of the ovum nucleus and nucleus of the second polar body, which is expelled during meiosis. The rate of inbreeding through gynogenesis is roughly equivalent to one generation of full‐sib mating. Meiotic gynogens are totally homozygous, with identical genes on each pair of chromosomes. They are more likely to die during embryonic development due to the higher frequency of deleterious genotypes found in 100% homozygous individuals.

Androgenesis, or all‐male inheritance, is more difficult to accomplish than gynogenesis, since diploidy can only be induced in androgens at first cell division, a difficult time to manipulate the embryo. Also androgens are totally homozygous, so a large percentage with deleterious genotypes will probably die.

Gynogenesis and androgenesis can be used to elucidate sex‐determining factors in fish. If the male is the homogametic sex when androgens are produced, the androgens will be 100% ZZ (all‐male). If the male is the heterogametic sex, XX and YY androgens will be produced, resulting in both sexes.

Fully inbred clonal lines have been produced in zebrafish, ayu, common carp, Nile tilapia and rainbow trout using both gynogenesis and androgenesis. Technology has not yet been shown to directly target and clone an individual fish. However, two successive generations of mitotic gynogenesis or androgenesis results in a clonal, although randomly generated population. These individuals within the clonal population should have identical genotypes throughout their entire genome. Since they will be homozygous for sex = determining genes, sex reversal must be used to perpetuate these populations. The performance of individuals within such clones is highly variable. Individuals with extreme homozygosity apparently lose the ability to respond to environmental variables in a consistent, stable manner and even micro‐environmental differences affect performance among individuals. As genetic variation decreases, environmentally induced variation increases and at a more rapid rate than in heterozygous populations.

7.8.2 Polyploidy

In normal development of fish, the diploid egg nucleus undergoes a mitotic division after a sperm penetrates through the outer membrane to fertilise the egg. One of the two 2 N nuclei resulting from this mitosis is extruded from the egg as the first polar body. The 2 N nucleus of the egg then undergoes a meiotic division and one of the resulting haploid (N) nuclei is extruded as the second polar body. The egg now contains two haploid nuclei: one from the egg and one from the sperm. These fuse to produce a diploid nucleus in a zygote, which then undergoes an initial division into two cells as the first step of embryonic development.

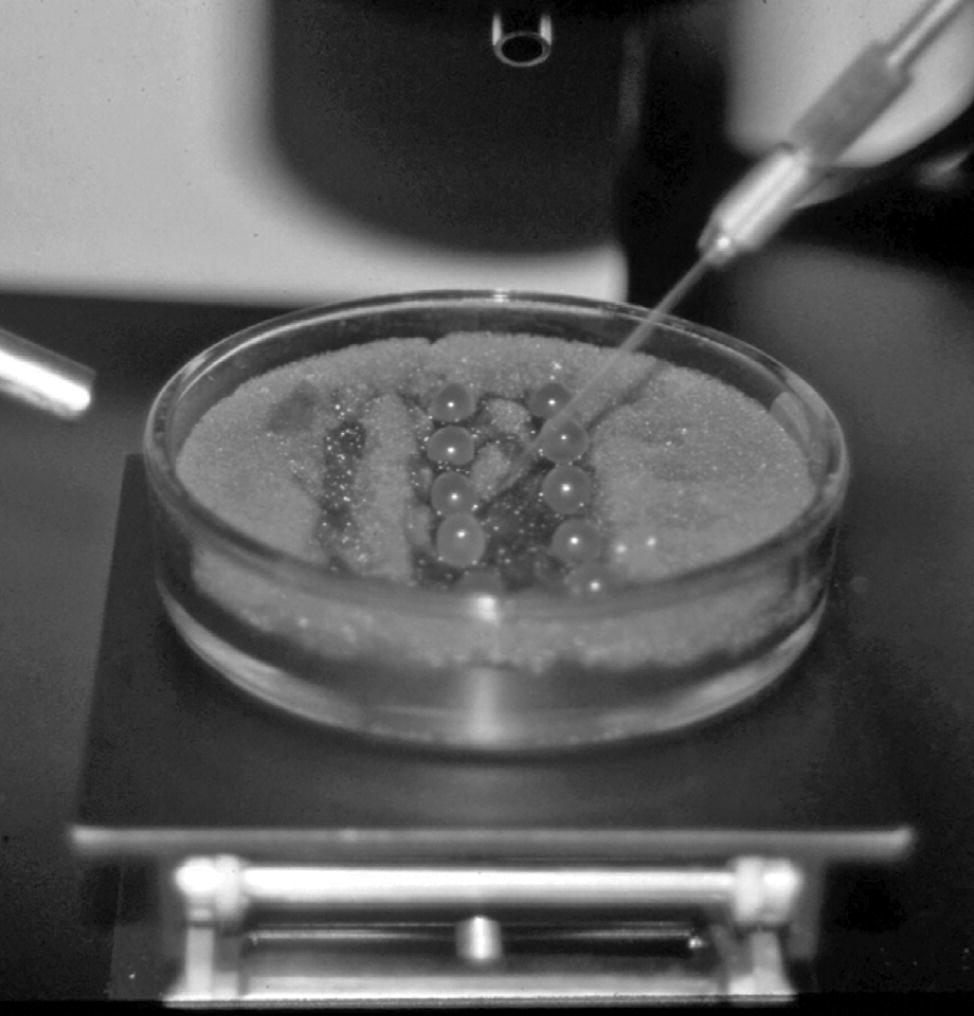

Polyploids, gynogens and androgens are produced by disrupting the above processes at various stages through shocks (Figure 7.6). Various chemical, temperature and pressure shocks are used shortly after fertilisation to produce triploidy and shortly before first cell division to produce tetraploidy (Figure 7.6). The timing of the disruption is critical and that, together with the most effective shock varies according to the species. Meiosis in shellfish is different from fish. In this case, triploids can be produced by blocking either the first or second meiotic division.

Figure 7.6 Stages of egg nucleus development when shocks are applied to produce triploids, tetraploids, gynogenetics and androgenetics.

Source: Tave 1990. Reproduced with permission from the World Aquaculture Society.

Polyploidy was thoroughly evaluated in fish and bivalve molluscs, especially during the period 1970–2000 (Dunham, 2011). Triploid evaluation usually emphasises the traits of growth, sterility and flesh quality. Triploid organisms are generally sterile. Females produce less sex hormones and, although triploid males may develop secondary sexual characteristics and show spawning behaviour, they are generally unable to reproduce. Triploidy can also be used to restore viability to nonviable interspecific hybrids.

Usually, triploidy will not improve growth rates in finfish until after sexual maturation, which is beyond market size for most species. However, there are exceptions: channel catfish triploids grown in tanks were larger than diploids at about 9 mo of age (90 g), which is shortly after the first emergence of sexual dimorphism in body weight. This is not advantageous commercially as triploid channel catfish and triploid catfish hybrids did not grow as rapidly as diploids in commercial environments, such as earthen ponds, and they had decreased tolerance of low DO. Triploid salmonid hybrids show similar or slower growth than diploid hybrids, but again may grow faster than controls once they reach maturity. Triploid chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) were less aggressive during feeding than diploid fish, but grew at the same rate as diploids.

In the case of common carp, most one year‐old triploids had undeveloped gonads and were sterile. The triploids grew slower than their diploid siblings under all conditions investigated. The potential for culture of triploid common carp appears questionable; however, results from India indicate that triploid common carp had a higher dress‐out % than diploid controls at least partially compensating for the slower growth.

Triploid performance can be influenced by strain and family effects. Diploid Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpines) grew faster than triploids. However, both ploidy level and family affected growth, and family predicted the performance of triploids. Triploids from fast growing families grew more rapidly than diploids from slow growing families.

Triploidy can have adverse effects on low DO tolerance. Triploid channel catfish and triploid catfish hybrids had decreased tolerance of low DO. Similar results have been obtained with salmonids.

Triploidy generally results in the prolongation of good flesh quality. The flesh of triploid rainbow trout females was superior to that of diploid females because post‐maturation changes were prevented. Combining monosex breeding and triploidy can produce fish with both superior growth rate and flesh quality. The triploid channel catfish had 6% greater carcass yield at three years of age, which was well past the time of sexual maturity and market size. However, carcass percentages and resistance to haemorrhagic septicaemia (caused by Aeromonas hydrophila) did not differ between triploid or diploid Thai walking catfish.

Triploidy can be very beneficial when applied to bivalve culture. Triploid induction in oysters, such as Crassostrea gigas, increases their size and flesh quality (Dunham, 2011). In Sydney rock oysters, Saccostrea cucullata (Figure 7.7), triploidy increased the flesh content of the oyster relative to diploid siblings (Kesarcodi‐Watson et al., 2001) (Figure 7.8). Triploid oysters do not produce large gonads, increasing marketability and flesh quality. This technique may or may not result in complete genetic sterilisation in oysters, as some triploids are able to reverse a portion of their cells back to the diploid state, creating potentially fertile mosaics (Dunham, 2011). Growth performance of sibling triploid and diploid oysters was correlated, but not their ability to reproduce. With regard to summer mortality, performance of triploid Pacific oysters was much more erratic than that of diploids.

Figure 7.7 Sydney rock oysters, Saccostrea cucullata. Croajingolong National Park, Victoria, Australia.

Source: Stevage 2007. Reproduced under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike license, CC BY‐SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 7.8 Relationship between total body energy, which to a large extent is soft body tissue, and shell length in adult and triploid oysters of Saccostrea cucullata. Each data point is a value for a single oyster.

Source: Kesarcodi‐Watson et al. 2001. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.

Benefits of triploidy are not as straightforward in other mollusc species. Growth and survival were no different for the blacklip abalone (Haliotis rubra) up to 30 months of age; however, the triploids had a more elongated shell and greater foot muscles than diploids. Triploids had higher feed consumption than diploids, but diploids had superior feed‐conversion efficiency. Triploids of greenlip abalone (Haliotis laevigata) had heavy mortality compared to diploids in several life stages. Diploids also grew faster than triploids, although the triploid abalone yielded up to 30% greater meat weight compared to same length diploid abalone during the spring‐summer maturation periods at 36 and 48 mo. Diploid abalone produced equivalent meat weights to triploid abalone between the maturation periods. Fatty acid composition of the meat was the same for triploids and diploids. In the majority of examples of various species of molluscs, triploidy was beneficial (Dunham, 2011).

Triploidy is the only technique that can guarantee that marine shrimp populations are skewed towards the faster growing sex, the female. Triploidy is also used to prevent the theft of elite stocks/germplasm.

In the Chinese white shrimp (Fenneropenaeus chinensis) triploids had a reduced number of haemocytes. This may be a key to explain the trend of reduced tolerance of low DO in finfish as well as having implications for crustaceans. The triploid shrimp grew faster during sexual maturation, but not before this time. Polyploidy is not commercially feasible for all species because the reproductive biology of some species places limitations on artificial propagation technology needed for triploid induction. For instance, mouth brooding of many tilapia, low numbers of eggs per batch and asynchronous spawning prevents or would greatly impede commercial production of triploid tilapia.

Tetraploidy is extremely difficult to accomplish in finfish. Most tetraploid individuals die as embryos. In the rare cases where a few tetraploids hatched, they were weak, slow growing and had low survival, but were fertile. Tetraploids are viable for bivalve molluscs. In this case, they are a valuable tool for crossing with diploids to make triploid populations (see above).

In summary, triploidy is usually not effective for increasing growth rate, but is very effective for sterilisation and increasing flesh quality. However, triploidy can be effective for increasing growth past sexual maturation and, in general, is effective for increasing size and growth in molluscs and shrimp.

7.8.3 Sex Reversal and Breeding

A variety of strategies and schemes utilising sex reversal and breeding, progeny testing, gynogenesis and androgenesis can lead to the development of predominantly, or completely, male or female populations (genetically and phenotypically) and populations with unique sex chromosome combinations. The goals of this strategy are to take advantage of sexually dimorphic characteristics such as growth and flesh quality, control reproduction or prevent establishment of exotic species. All‐female populations have been successfully developed for salmonids (Figure 7.9), cyprinids and tilapias using the scheme presented in Figure 7.10. Populations of YY males have been established for Nile tilapia on a commercial scale and on an experimental scale for channel catfish (Dunham, 2011), and the procedure is illustrated in Figure 7.11. Genetic production of monosex populations has the advantage of reduced hormone use compared to direct sex reversal using hormones, which of course has environmental and regulatory implications.

Figure 7.9 Percentage of all‐female, triploid and mixed‐sex rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss, utilised in and from 1986 to 1998, illustrating the increasing and almost exclusive adoption of the all‐female production technology

Source: D. Penman. Reproduced with permission from Dr Penman. Data from Marine Scotland.

Figure 7.10 Scheme for producing all‐female XX populations of fish.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Rex Dunham.

Figure 7.11 Scheme for producing all YY male populations of fish.

Source: Reproduced with permission from Rex Dunham.

Sex‐determining mechanisms were reviewed by (Devlin and Nagahama 2002, Dunham, 2011). While many commercially cultured families show the usual XX/XY sex determination mechanism (carps, salmonids), where XX are females and XY are males, others may be sequential hermaphrodites (change sex as they mature), such as gilthead seabream and groupers, or have temperature‐controlled sex determination in addition to an XX/XY mechanism such as in Nile tilapia and hirame. Different mechanisms may also be found in closely related species:

- the Nile tilapia has the XX/XY system with the female being homogametic, XX, and the male XY;

- the blue tilapia has a WZ/ZZ system with the male being homogametic, ZZ, and the female,WZ.

Similar differences in closely related species are likely to exist for centrarchids, ictlaurids and perhaps others. Additionally, sex determination has polygenic influences in some species.

Sex ratios of Nile tilapia at 36 °C become a quantitative trait. Three generations of selection for maleness resulted in 93% male progeny, whereas selection for femaleness resulted in a sex ratio of 1:1. Heritability was high for maleness. The response to selection for femaleness was the result of a lower heritability coupled with maternal effects.

Sex reversal and breeding has allowed production of YY channel catfish males that can be mated to normal XX females to produce all‐male XY progeny. Males that are XY can be turned into phenotypic females by use of sex hormones and can then be used as breeders. The sex ratio of progeny from the mating of XY female and XY male channel catfish was 2.8 males: 1 female, indicating that most, if not all, the YY individuals are viable. All‐male progeny are beneficial for catfish culture, since they grow 10‐30% faster than females. YY males are also viable in salmonids, Nile tilapia and goldfish. The channel catfish YY system has stalled, however, because YY females have severe reproductive problems, and large‐scale progeny testing is not economically feasible to identify YY males. A combination of sex reversal and breeding to produce all‐female XX rainbow trout is now the basis for stocking most of the culture industry in the United Kingdom, as is the case for the chinook salmon industry in Canada. All‐female populations are desirable, in this case, because males undergo maturation at a small size, and have poorer flesh quality. Monosex chinook (O. tshchawystcha), and coho crossed with chinook have also been produced.

YY male Nile tilapia were as viable and fertile as XY males, and capable of siring 96% male offspring. YY genotypes can be feminised to mass produce YY males with YY × YY matings, thus eliminating the need for time‐consuming progeny testing to discriminate XY and YY male genotypes. This has enabled the production of YY males and then all‐male progeny, XY, after crossing with normal XX females. These normal all‐males derived from the YY males are sold commercially as ‘genetically male tilapia’ [GMT®] to distinguish them from sex‐reversed male tilapia, The YY male technology provides an effective solution to culture problems with early sexual maturation, unwanted reproduction and overpopulation.

Sex ratios vary widely between spawnings of Nile tilapia, but at the population level, they maintain a normal distribution of around 1:1 males to females. Sex ratios vary among strains of Nile tilapia and greater heterogeneity was found in the sex ratios of families collected from a mix of strains, some of which were introgressed with the Mozambique tilapia (O. mossambicus). YY males crossed with XX females produce 95–100% males and there were no females among 285 progeny from the mating of a single YY male crossed to 10 separate females indicating the potential to select for lines that can produce 100% males. In fact, three generations of gynogenetic Nile tilapia have been produced, and males from this line were used for mating with gynogenetic Nile tilapia females, resulting in consistent production of 100% males.