Chapter Three:

How Does Guided Reading Fit into the Rest of the Literacy Program?

Read aloud, shared reading, guided reading and independent reading are connected and equally important in supporting students as they establish a reading process that focuses on meaning making.

Burkins and Croft, 2010

At a workshop I was conducting on flexible grouping, a reading coordinator approached me during a break. Questioning my suggestions that some grouping arrangements could focus on something other than leveled texts, she argued for the need for a plan like her school had recently implemented. In her school, they guaranteed that every day every child would read appropriate leveled text for 30 minutes. They worked to reorganize the school so that children could move between classrooms to appropriate groups based on their reading levels and often to work with other teachers during that 30-minute block. While acknowledging the importance of their effort to guarantee that every child received at least 30 minutes of guided reading instruction with appropriate texts was important, I did wonder what happened to each child during the balance of the day in that school. After all, even after that 30-minute period, there were six hours of instruction remaining in the school day.

Guided reading works best when it is part of a comprehensive literacy program. Routman (2000) pointed out that no matter how powerful small group guided reading sessions can be, they are just one element of a comprehensive literacy program. No one “component” can carry the burden of accelerating the growth of all readers. In telling her story, Cathy Mere (2005) said that she had to remind herself that, in her classroom, teaching and learning happened all day—not just during guided reading. “If I haven’t met with a child in a guided reading group, it doesn’t mean that I haven’t taught that child” (p. 124). Burkins and Croft (2010) noted the number one misunderstanding about guided reading is that it is the only time reading is taught. They challenged the idea that what a teacher did during guided reading was any more important than what a teacher did during the read-aloud, shared reading, and independent reading components of the literacy program. “Guided reading, however, is most valuable when we strategically support it across the gradual release of responsibility” (p. 11).

It is important to start with the assumption that if teachers are going to accelerate the growth of all readers, effective instruction needs to be a focus throughout the literacy program (and the school day)—not just relegated to one daily 30-minute period. Borrowing the language of Margaret Mooney (1990), I often tell the pre-service teachers with whom I work that a comprehensive literacy program can often be summed up in three words: “to,” “with,” and “by.” You need to read to your students, you need to read with your students, and you need to have your students read by themselves. This also means you will sometimes use large groups for reading to and with your students during read-alouds and shared reading; small groups for reading with students during guided reading; and individualized approaches to encourage students to read by themselves. It also means that there are some things the teacher does like read-alouds, some things the teacher and students do together like shared and guided reading, and some things the students do by themselves like independent reading. A comprehensive literacy program acknowledges that all grouping arrangements are critical because they have different purposes, different available levels of support, and/or a different literacy focus.

This becomes even more apparent when we look at what happens in a typical day in an elementary literacy program. In the last chapter, I built a case for the continued importance of guided reading as a critical dimension of the literacy program, but children still spend significant time in the large group setting (Kelly & Turner, 2009). This shouldn’t be surprising because, for teachers, the most efficient use of time and resources is with a whole group setting—working with all children at the same time using the same materials. This is typically represented by what we call “universal instruction” in RtI frameworks. It makes sense in a literacy block for activities like read-alouds and shared reading. In a gradual release model, this is also the best setting for modeling and demonstrating skills and strategies needed by all students. In a two-hour literacy block, it is often recommended that approximately 30 minutes be allocated for that purpose. However, in most cases in whole group instruction, the teacher uses a text at or above grade level. When that text is set aside, it is accessible to students who read at or above level but not to those students who would struggle to read at that level. If teachers are not required to consider how to support all learners during whole group instruction, they may be less successful in reaching those students who may need the instruction the most.

Once the teacher moves to guided reading, there is more intentionality about considering how to support all learners. As the survey results revealed, the teacher may schedule an additional hour or so to meet with three to four guided reading groups. The teacher carefully selects texts at the level of the readers in that group so that instruction can be targeted to the learners’ needs. This part of the literacy block usually supports students the most. However, the small group work is only part of the time during this block. The teacher must also be very intentional in considering how to support all learners when they are working on their own. The students will typically spend most of this time working independently away from the teacher. If this time is to be successful in reaching all students, especially those in need of the most support, the teacher must carefully consider how to structure this time. Without that consideration, guided reading might not be an effective use of instructional time. (Chapter Six looks more closely at how to do that.)

When the teacher moves to the content areas, it often means a return to whole class instruction with the same text for all students. If that is another 30-minute block of time, students in need of the most support are spending even more time with texts that are not within their reading levels. As Figure 3A reveals, by the end of a typical two-hour instructional block, students in need of the most support often receive the least amount of instructional time with texts within their levels. If teachers are not intentional about the independent time the learners get, the amount of time with appropriate texts erodes even further. Finally, if the teacher walks away from guided reading for whatever reason, it is easy to see how some students could move through the entire block with virtually no time with appropriate text. Clearly, guided reading cannot carry the burden of accelerating the growth of all readers, especially those who might need our help the most. In fact, if more attention is given to fostering the conditions for learning in the classroom and to the other critical elements of a literacy program, the need for guided reading might actually be reduced. Let’s look closely at those conditions and elements and how to attend to them.

Figure 3A: Typical Time Allocations for Accessible Appropriate Texts

- Readers Above Level

- Shared Reading: 30 minutes

- Guided Reading: 20 minutes

- Independent Reading: 40 minutes

- Content-area Reading: 30 minutes

- Total Minutes with Appropriate Accessible Text: 120 minutes

- Readers At Level

- Shared Reading: 30 minutes

- Guided Reading: 20 minutes

- Independent Reading: 40 minutes

- Content-area Reading: 30 minutes

- Total Minutes with Appropriate Accessible Text: 120 minutes

- Readers Below Level

- Shared Reading: 0 minutes

- Guided Reading: 20 minutes

- Independent Reading: 40 minutes

- Content-area Reading: 0 minutes

- Total Minutes with Appropriate Accessible Text: 60 minutes

Conditions of Learning

How does a teacher start maximizing the impact of guided reading with other critical dimensions of a comprehensive literacy program? She might begin by considering the conditions that lead most learners to become successful readers and writers. There is a helpful framework by Brian Cambourne (1995), who identified eight critical conditions for language learning. Reflecting on each of these eight conditions often leads me to see aspects of literacy programs that are strong and others that can be strengthened. By attending to those conditions in need, teachers may actually improve the power of other aspects of the literacy program like guided reading. Guided reading is only as strong as the other elements that surround it.

Cambourne theorized that to become a language learner (and I might argue to become a learner of any skill or process from athletics to music, from hobbies to occupations), there are eight conditions that must be present. The list that follows is my interpretation of what is important in each of these conditions:

- Immersion: The learner needs to be surrounded with what is needed for learning to become a reader and writer. This means having access to the materials and resources needed for reading and writing and being placed in a physical environment that facilitates growth as a reader and writer.

- Demonstrations: On the cognitive side, the learner works with an expert, who can provide effective models of how reading and writing skills, strategies, and processes work. On the affective side, the learner establishes a relationship with someone who is passionate about reading and writing in his or her life.

- Practice: The learner is provided time to engage in reading and writing processes to show the ability to apply and use what was taught.

- Feedback: The learner works with an expert coach, who provides guidance as he or she practices reading and writing tasks, seizing at-the-moment teaching opportunities to help the learner move forward. When the learner works independently, targeted response is provided when the teacher meets with the learner to scaffold him or her from one point to another.

- Approximations: The learner is encouraged to perform while becoming increasingly competent. The learner is allowed to—even encouraged to—take risks in learning to read and write as developmentally appropriate without a demand for accuracy or perfection. Developmental leaps are not dismissed or marginalized but celebrated as steps in the journey to becoming a reader and writer. The emotional climate of the classroom provides a safe atmosphere for the learner to take these risks.

- Expectations: The learner works with adults who see him or her as a reader and writer. The program works with an asset model focused on what a learner can do and avoids focusing on what a learner can’t do. Language used in the classroom positively shapes a learner so he or she sees him- or herself as a reader and writer. Everyone is an inside player in the reading and writing club.

- Engagement: There’s a saying that “you can’t lead a horse to water, but you can salt the hay.” Teachers can surround a learner with the other conditions, but the learner must actually participate in the task. He or she must move from the instruction to the application. Engagement usually results when the learner is motivated about, interested in, and passionate about the reading and writing opportunities. Engagement is what the teacher does to salt the hay. The learner must know he or she can succeed, want to succeed, and know how to succeed (Opitz & Ford, 2014).

- Responsibility: But ultimately, the horse must drink the water. The learner must take hold of the opportunity to read and write. He or she moves beyond compliance and develops an internal force that propels him or her toward reading and writing without external motivations (Schlechty, 2002). The learner has a sense of urgency and takes charge of his or her reading and writing life (Boushey & Moser, 2006). The learner IS a reader and writer and finds the joy in those activities beyond the school walls throughout his or her life.

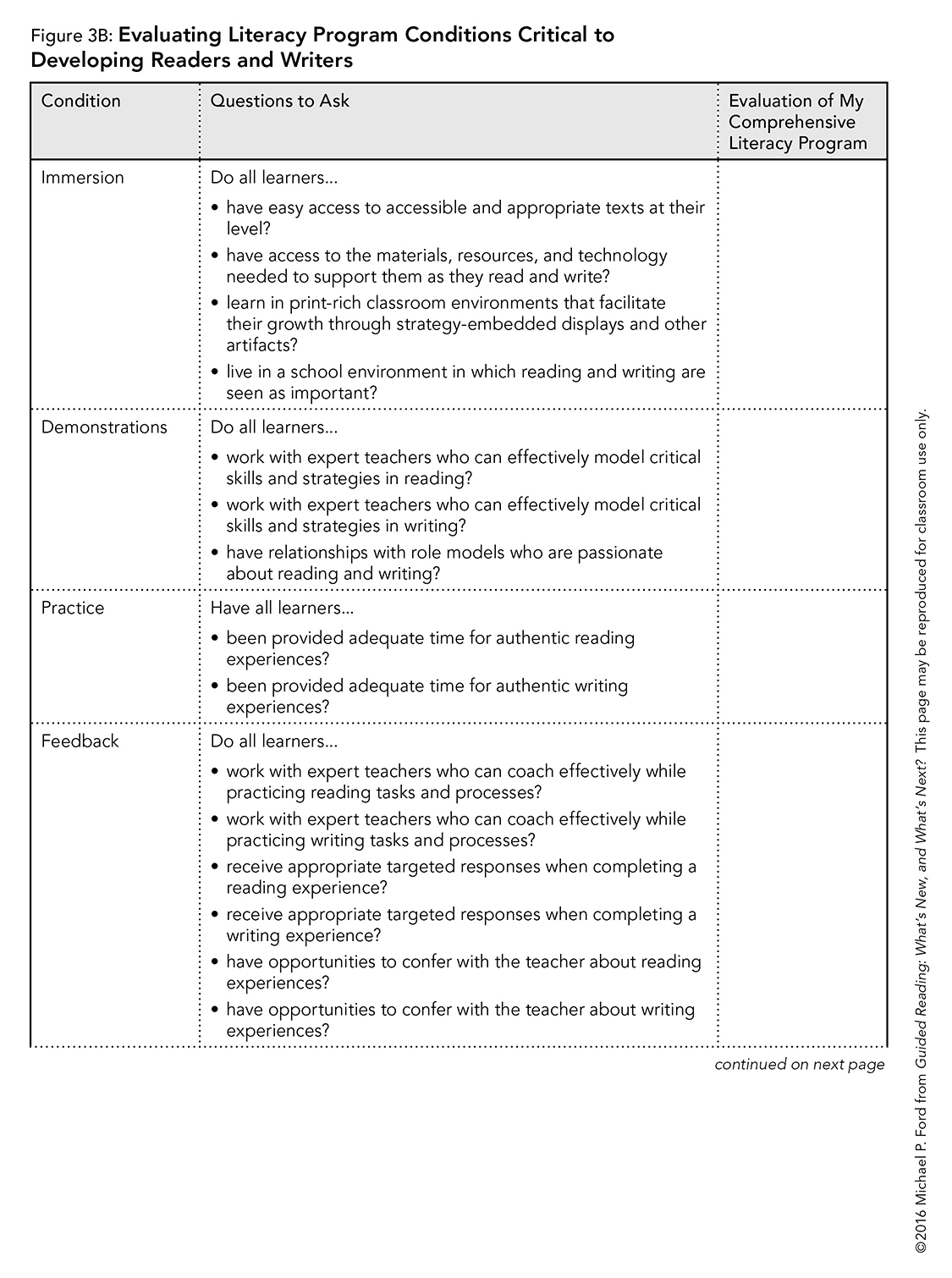

In Figure 3B, I have provided a grid that can be used to help teachers evaluate the power of the conditions of language learning in their classroom literacy programs. Remember that if these conditions are being met in a classroom, guided reading will operate in a context that should enhance its use.

Elements of the Literacy Block

It becomes increasingly obvious that if the conditions are right in a classroom, literacy instruction will help most students become the readers and writers we desire. Guided reading becomes an instructional tool to reach those in need of additional support, but it does not have to carry that responsibility for the entire literacy block. This is especially true if the conditions are operationalized across elements within the block. In this section, we’ll look at how to strengthen three other key elements of the literacy block: read-alouds, shared reading, and independent reading.

Read-alouds

As time becomes the biggest constraint on classroom instruction, it often influences decisions to reduce or even eliminate instruction that is not essential. I would argue like others (Layne, 2015; Fox, 2013) that we need to rethink the read-aloud component of the literacy block. The traditional image of the teacher sitting down with children after lunch and reading from a specially endeared chapter book for 30 minutes a day needs to be reconceptualized.

When considering the conditions of language learning, read-alouds are a critical vehicle for immersing learners in reading and thus increasing the power of guided reading. Every book that a teacher reads aloud is a book that remains in the head of the child. Read-alouds provide many opportunities for teachers to demonstrate to students how the reading process works and put the teacher’s love of reading on display. There is time during a read-aloud in which approximations are made (sometimes risks and celebrations occur naturally, sometimes more intentionally), so a teacher can show how performance, not perfection, is the goal in reading. Read-alouds are the time to convey expectations that everyone can do this and everyone should be engaged in doing this. Structured right, read-alouds actually can invite students to take over the responsibility for reading the text being shared.

Here are some tips in strengthening the read-aloud time, so it can provide support for the guided reading that follows.

- If time is a constraint, move beyond the one-period-a-day vision of read-alouds and think about sprinkling shorter read-alouds throughout the day (Oczkus, 2012). Using a short read-aloud can actually be a great way to also add power to transitions during guided reading.

- Be more intentional about the selection of the read-aloud titles. Laminack and Wadsworth (2006) suggest at least six purposes for read-alouds: address standards, build community, demonstrate craft, enrich vocabulary, model fluent reading, and entice children to read independently. Consider selecting texts that make connections to instruction that will follow during guided reading groups or to independent work away from the teacher.

- Select texts at multiple levels for your read-alouds. The use of easier texts, including picture book formats, with older learners will help make these books seem more acceptable and less stigmatized. The end result is when these texts are included in guided reading, they are met with less resistance.

- Select texts that will lead to independent reading habits. Start a series, introduce an author (especially one who writes at different levels), or sell a genre or format the students haven’t experienced. This can lead to greater engagement in read-to-self opportunities when away from the teacher.

- Consider how to use read-aloud choices to move students to increasingly complex texts and/or to expand their reading habits. Sometimes students self-select in a manner that keeps them rooted in easy texts when they can handle something more complex for their reading habits. This may open up acceptance of texts used during guided reading that might be different from the readers’ current habit.

- Use the read-aloud time to help students expand their visions of who readers are and what texts are by choosing alternative formats (i.e., readers read magazines, newspapers, pamphlets, brochures, graphic novels, comic books, online texts, etc.). Send a message that readers read lots of different things. It will strengthen the identities of readers who do not see themselves within the typical “readers read books” image. Students with positive identities will find greater value in guided reading instruction.

- Plan your read-aloud moments so they leave students wanting more. Think about stopping points that would create interest in returning to the text either with you or on their own. Consider whether a read-aloud can be finished during guided reading.

- Make sure that you are prepared for the read-aloud time. Invest in simple techniques to improve your read-aloud abilities so that your love of reading is always on display. It can start simply by varying your pace, volume, and pitch to add variety to your voice (Fox, 2008). Make sure the students know you are passionate about what you are teaching them to do using guided reading.

- Put your reading life on display during the read-aloud time (Morgan, Mraz, Padak & Rasinski, 2009). Talk about why, when, and where you read. Share how you keep track of your reading. (I archive on Goodreads.com.) Tell where you find and keep your books. Identify who influences your choices and with whom you share what you are reading. The stories of your reading life can spill over to guided reading sessions and encourage students to share similar aspects of their reading lives. This will ultimately help them as they shape stronger identities as readers.

- Select read-aloud texts that have central characters who embrace reading. Find characters who have a sense of urgency about reading, reveal strategies about their reading, or use reading to learn. Always consider the message you are sending to students about reading, school, and learning in the texts you share with students. (See Figure 3C.) For older students, you might read about some characters who struggle a bit with their reading as a catalyst for conversations about how to strengthen their reading identities. (See Figure 3D.)

Figure 3C: Read-aloud Titles Featuring Characters with a Love of Reading

- Again! by Emily Gravett (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

- A young dragon becomes a bit agitated when he can’t convince his tired mother to read his favorite bedtime story over and over again.

- Lola at the Library by Anna McQuinn (Charlesbridge, 2006)

- Tuesday is Lola’s favorite day because she gets to go to the library with her mom and bring home new books to read.

- Roger Is Reading a Book by Koen Van Biesen (Eerdmans Books for Young Readers, 2012)

- Roger must figure out a way to quiet down his neighbor so he can concentrate on his reading.

- Calvin Can’t Fly: The Story of a Bookworm Birdie by Jennifer Berne (Sterling Books, 2010)

- Calvin decides he would rather read than learn to fly, which comes in handy when the birds find themselves flying right into a hurricane.

- Look! by Jeff Mack (Philomel Books, 2013)

- Trying to get attention from a boy whose eyes won’t leave the screen, a gorilla finds a book might be the best way to start the bonding.

- The Snatchabook: Who’s Stealing All the Stories? by Helen Docherty (Sourcebooks Jabberwocky, 2013)

- A mystery is solved when a bunny stays up late to see who has been stealing all the bedtime stories and a new creature is discovered.

- Cat Secrets by Jef Czekaj (Balzer and Bray, 2011)

- A mouse waits patiently for unsuspecting cats to let go of their book so the mouse can read about the cats’ secrets.

- Margo and Marky’s Adventures in Reading by Thomas Kingsley Troupe (Picture Window Books, 2011)

- These two friends prove you can have any exciting adventure you want as long as you read.

- This Book Just Ate My Dog! by Richard Byrne (Henry Holt and Co., 2014)

- The dog is only the first thing that is swallowed by a book and disappears in the center of the book as the character tries to figure out how to get it back.

- Duncan the Story Dragon by Amanda Driscoll (Knopf, 2015)

- Duncan’s imagination always catches fire when he reads (and so does his books). So he goes in search of the right buddy who will help him read.

- My Pet Book by Bob Staake (Random House, 2014)

- A young boy decides a book may be a better pet than an animal but panics when his book goes missing.

- We Are in a Book! (An Elephant and Piggie Book) by Mo Willems (Disney Hyperion, 2010)

- Elephant and Piggie discover the joy of being in a book, and a reader is reading their story.

- How Rocket Learned to Read by Tad Hills (Schwartz & Wade, 2010)

- Rocket the dog finds his way through the alphabet and words as he learns to read.

- Ninja Bunny by Jennifer Gray Olson (Knopf, 2015)

- A bunny reads his book, listing rules about becoming a ninja while learning the value of not working alone.

- You Should Read This Book by Tony Stead (Capstone, 2015)

- This book actually helps kids decide what books they may want to read next.

Figure 3D: Read-aloud Books with Characters Strengthening Their Reading and Writing

- Babymouse: Puppy Love by Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm (Random House, 2007)

- Make sure you can project this graphic novel as you share it aloud. Babymouse’s reading selections like Charlotte’s Web and National Velvet guide her decisions about getting the best pet.

- Escape from Mr. Lemoncello’s Library by Chris Grabenstein (Random House, 2013)

- Kyle wins an overnight stay in a new library designed by his favorite game maker, but escape becomes dependent on solving a high-stakes series of clues and puzzles.

- Nightmare at the Book Fair by Dan Gutman (Simon and Schuster, 2008)

- Trip hates to read, but he does help the PTA set up the book fair. Unfortunately, a stack of boxes fall on Trip, and his dreams start coming in a variety of genres. With a different genre featured in each chapter, it’s a great way to introduce the categories as students figure out what they like.

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Dog Days by Jeff Kinney (Amulet Books, 2009)

- Greg’s mom starts a summer reading club called Reading Is Fun Club for the neighborhood boys.

- George Brown, Class Clown: Trouble Magnet by Nancy Krulik (Grosset & Dunlap, 2010)

- George uses his reading to learn about Hawaii when he is assigned a class project on the state. His desire to provide a model of Hawaii’s volcanoes keeps the learning moving forward.

- Squish: Brave New Pond by Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm (Random House, 2011)

- Like with Babymouse, make sure you can project this graphic novel as you share it aloud. Squish is always reading his favorite comic about Super Amoeba, who provides inspiration and insight for life’s problems.

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid: The Long Haul by Jeff Kinney (Amulet Books, 2014)

- Students might enjoy Greg’s defense of his favorite reading series that he takes with him on a long family road trip. His strong defense of The Underpants Bandits series may give students some ideas for advocating for their favorite authors.

- Lunch Lady and the League of Librarians by Jarrett J. Krosoczka (Knopf, 2009)

- As the kids’ excitement about reading grows with an upcoming book fair and read-a-thon, the Lunch Lady tries to figure out what is going on with the librarians, whose demeanors have all suddenly changed.

- Star Time by Patricia Reilly Giff (Wendy Lamb Books, 2011)

- The after-school program kids, better known as the Zigzag Kids, use their reading and writing to get ready to put on a show.

- Dying to Meet You (43 Old Cemetery Road) by Kate Klise (HMH Books for Young Readers, 2009)

- Through a series of letters, notes, and memos, readers learn that a bestselling author moves into an old house hoping to crack his writer’s block but doesn’t know that a young boy, his cat, and a ghost already live there.

- Moxy Maxwell Does Not Love Stuart Little by Peggy Gifford (Yearling, 2007)

- So what happens when one postpones summer reading until the day before school starts? You have to suffer the consequences. Such is the case for Moxy, who learns the hardest thing about summer reading is getting it started. Great book to start the year and talk about the importance of choice in our book selections.

- The Ellie McDoodle Diaries: New Kid in School by Ruth McNally Barshaw (Bloomsbury, 2008)

- Ellie negotiates all the obstacles at being the new kid in school and finds solace in her reading and writing. Those talents lead new friends to her.

- Eleven by Patricia Reilly Giff (Wendy Lamb Books, 2008)

- The discovery of contents in a locked box in his attic hint at the fact that Sam may have been kidnapped. This motivates him to get help with his reading from his friend Caroline so they can discover what happened in his past.

- My Life as a Book by Janet Tashjian (Henry Holt, 2010)

- Central character and reluctant reader Derek uses a strategy of drawing little cartoons in the margins of his book (and they are in this book) to help him remember hard vocabulary words. His reading takes off when he tries to solve a mystery about his past.

- The Island of Dr. Librisby Chris Grabenstein (Random House, 2015)

- Billy’s summer island vacation takes an interesting turn when the books from a special library actually have characters that come to life.

Shared Reading

Guided reading may not be the most efficient way to provide instruction if the students across small groups often share similar needs and perform at similar levels. One teacher I observed during guided reading time had divided her young readers into multiple groups and prepared things for them to do while they were working away from her. I watched her rotate through her groups and conduct essentially the same lesson with each small group. The advantage may have been that she could attend to individual children when they were in small groups or perhaps the students could attend to the instruction when they were in small groups, but this teacher could have packed more into her day if she used a whole group model.

Shared reading, whole class instruction, and large group settings are a more efficient model for providing universal instruction, or initial instruction needed by all learners. It allows the teacher to conserve on both the amount of resources and class time needed for instruction. With all students in the same place at the same time using the same resources, effective shared reading may help support the guided reading dimension of the literacy block.

Considering the conditions of language learning can help strengthen shared readings. Shared readings are a time to create, add to, and interact with resources in an interactive classroom environment. Shared readings are designed for demonstrating and modeling. Learners can be shown how reading works, can stay with the teacher as they practice together, and can be observed by the teacher as they practice on their own. As students practice under the watchful eye of the teacher, feedback can be given and instruction adjusted. License can be given for approximations and can be judged immediately in case additional instruction is needed. Like read-alouds, shared readings provide another opportunity to establish the expectations that everyone can do this and should be engaged in doing this. The shared readings can be intentionally designed so that by the end of the lesson, the learner can take responsibility for finishing the reading experience.

Here are some tips for strengthening the universal instruction in your shared readings so it can support the guided reading that follows.

- When teaching specific strategies, skills, or behaviors, plan universal instruction so that it follows a gradual release of responsibility model. Have modeling followed by opportunities for students to practice collectively with your guidance and independently under your watchful eye. Boyles (2004) reminds teachers that there is a need for both structured practice (teacher does while students help) and guided practice (students do while the teacher helps). In some cases, the actual guided practice might be during the guided reading lesson. When this occurs, link the large group lesson to the small group lesson (Burkins & Croft, 2010).

- With explicit instruction, structure the lesson to include declarative knowledge (what the strategy is), conditional knowledge (why and when the strategy should be used), and, most important, procedural knowledge (how the strategy is actually done, step-by-step). This will better prepare students to apply the strategies during guided reading sessions.

- Using explicit instruction, show that multiple strategies are used at the same time. Any one text offers opportunities to show that you could and should use many ways to think about the text in understanding and responding to it. Boyles (2004) recommends the integration of kid-friendly language in thinking aloud to model strategic thinking: “I’m noticing, figuring out, picturing, wondering, guessing, making connections,” etc. This provides learners with language to use in articulating their strategic thinking during guided reading sessions.

- Try to capture what is taught in hard copy. The lesson will then lead to a resource that can be added to the classroom environment and referred to at other times for additional instruction or student use. Strategy-embedded charts or posters work well and can be referred to during guided reading lessons as well. Clear step-by-step processes may be most useful.

- Select the texts you use for shared readings, or mentor texts, with greater intentionality. Shared readings are another opportunity to feature texts at multiple levels, in a variety of formats, from a variety of authors, and across a variety of genres. Use the shared experiences to continue to expand the vision of who readers are and what they read, so more texts become acceptable during guided reading sessions.

- Consider the use of alternative modes (pictures, music, video) to introduce a strategy in a more concrete and accessible manner than with just a text-based example. A strategy like compare/contrast and a tool like a Venn diagram can be introduced using two pictures, two songs, or two short video clips. (Hint: Embed a hyperlink to the music or video in your Venn diagram on your interactive whiteboard.) This introduction can lay down the thinking for a print-based application during guided reading instruction.

- Set up the shared experience so that it can be revisited during independent work time away. Provide access to the materials and resources so that it becomes a learning station that can engage some students while you’re working with a guided reading group.

Independent Reading

Routman (2000) reminded us that students need to do more reading and struggling readers need to do even more reading. Her conclusion is echoed by others. “Everyone has heard the proverb: practice makes perfect. In learning to read it is true that reading practice—just reading—is a powerful contributor to the development of accurate, fluent, high-comprehension reading” (Allington, 2013, p. 43). By the end of elementary school, the greatest difference between successful readers and those who are less successful is the amount of practice in which they engage in reading (Stanovich, 1986). A classic study by Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding (1988) revealed that fifth-grade students who read at the 20th percentile reported reading 3.1 minutes per day. Those reading at the 50th percentile read 12.9 minutes a day, but those reading at the 90th percentile read approximately 40.4 minutes a day. The data are correlational, so it is easy to conclude that there seems to be some relationship between the number of minutes read and performance on traditional reading measures. Similar data emerge when we look at national and international assessments of reading performance (Allington, 2013). Unfortunately, if the relationship between time spent reading and performance extends beyond fifth grade, the gap grows wider. Those who read the most will read even more and get even better. Those who read the least will not grow stronger and will have even less reason to keep reading. One hopeful possibility rests in what could happen if we could just increase each reader’s reading time 10 more minutes a day. The lowest readers would increase their reading time more than 300 percent. Yes, the other groups would also go up, but it would have its greatest impact on those who need the practice the most. It seems clear that guided reading without a strong independent reading program will fall short of helping teachers close these gaps.

Reflecting on the conditions of language learning can help to evaluate independent reading programs. Independent reading programs rely on immersion in an environment in which there is virtually endless access to things to read and resources that can be used to support readers. Independent reading is the critical time to provide the practice readers need to grow their habits. To enhance the experience, consider structuring reading so peers can provide partners feedback or learners can confer with you to get that individual feedback. With encouragement, independent time provides an opportunity for learners to take chances and make approximations. And if the expectation is set that this time will be full of engagement and joy, learners will take responsibility as readers.

Let’s look at some tips for bringing more power to the independent reading portion of a comprehensive literacy program so that it can support guided reading.

- Building a classroom library is critical, but the library must be built so that almost all books can be read by almost all readers. Looking closely at one’s current collection and thinking about how many titles can be read by any reader may provide a baseline for how to add to the collection. The more texts readers can read away from the teacher, the more engaged they will be during that independent time. Engagement will lead to greater stamina and more practice, which actually helps students achieve the gains desired from guided reading. (In Chapter Four, I will look more closely at texts, but remember that texts must be seen as both accessible and acceptable by the learners.)

- Organize books with less emphasis on levels. Book centers that contain tubs of books all arranged by levels can make certain books less appealing to most students. Books organized by genres, topics, themes, authors, and formats allow different levels of books to be placed in the same tubs. This setup can lead to readers at different levels discussing their choices around the same focus, which rarely happens if the books are organized by levels. This will help take the focus off the level of the texts used in guided reading and shift attention to more important aspects like the topic, theme, format, or genre. Make sure a variety of books are displayed and promoted in the physical classroom space as well.

- Support learners in the texts they choose to read independently. Intentionally teach learners how to select appropriate texts for their independent reading time, but don’t be afraid to make suggestions. Language like “I thought you might like this” or “See what you think about this” allows for influence but leaves the final choice to the reader. Suggestions also help reduce the amount of time spent choosing books so more time is spent reading books.

- Structure guided reading so that it can lead students to texts to read during independent time. For example, consider turning the balance of the reading over to students to complete during independent reading time. Also introduce related texts for independent reading time.

- Using explicit instruction, intentionally address what independent reading is, what ways we can read independently, what happens when we read silently, where the best places to read in the classroom are, and what the best ways to make good use of our independent reading time are (Boushey & Moser, 2006; Opitz & Ford, 2014). This will minimize management issues that can distract attention from guided reading instruction.

- Allow time for students to share what they have been reading, thinking, and learning from independent reading time. This time to share provides a meaningful outcome for the reading activities and may encourage others to read the same books. With a greater sense of purpose, students may also be motivated to improve their reading during guided reading sessions. A small part of guided reading time could include having students share their independent reading experiences to strengthen the link between both.

- Integrate the use of individual conferences to meet with readers about what and how they were reading. This sets up an additional opportunity to assess and interact with individual students outside the guided reading setting. It provides a chance for you and the student to discuss goals to work on during guided and independent reading time, which will keep the student focused.

- Build in some minimal accountability for independent reading like documenting progress toward personal goals. Avoid extrinsic rewards, public displays, or tracking the number of books or number of pages read. Focus more on effort and time. This shifts the focus from what is read to reading. Independent reading is where identities about being a reader are being shaped. We want all students to come to the guided reading instruction with a positive view of who they are as readers. Social comparisons and external judgments usually interfere with that.

Other Considerations

In this chapter, I encouraged teachers to look carefully at the eight conditions needed for language learning. I also narrowed my focus by discussing ways to improve the quality of three key elements of the literacy program that go beyond guided reading. Obviously, there are other factors that can be considered in making sure guided reading fits well within a literacy program. For each of the reading elements, there is also a parallel element related to writing instruction that could be examined and strengthened as needed: writing aloud, shared writing, guided writing, and/or independent writing. Likewise, other aspects of language arts instruction (speaking, listening, viewing, and producing) could also be evaluated. The stronger each element of the language arts program is, the clearer the role and responsibility of guided reading becomes. One could also examine other places in which students receive instruction and practice: home connections, summer programs, and support programs. Manners of interaction related to classroom discourse and engagement strategies could be another focus. However, one needs to start somewhere. My suggestion is if a literacy program can at least guarantee that all learners are surrounded by the conditions of language learning and have access to effective read-alouds, shared reading, and independent reading opportunities, guided reading should be able to play an appropriate and effective role in helping all students thrive.

For school leaders and educators looking for a more thorough examination, Dorn and Soffos (2011) provide a comprehensive tool called “Environmental Scale for Assessing Implementation Levels (ESAIL)” in their book Interventions That Work. The tool requires that educators look at 10 criteria: literate environment, classroom organization, data-based instruction and research-based interventions, differentiation, school-wide progress monitoring, literacy coaches, collaborative learning communities, plans for systematic change, technology, and advocacy. In Engaging Minds in the Classroom, Michael Opitz and I (2014) provide an additional evaluative tool, which specifically targets the affective components of a school literacy program related to students, teachers, materials, assessments, and the physical environment.