Chapter Six:

What Is the Rest of the Class Doing During Guided Reading?

Clearly, the power of the instruction that takes place when students are learning independently must rival the power of the instruction that takes place with the teacher if all children are to maximize their full potential as readers.

Opitz and Ford, 2001

When classroom literacy programs returned to the use of small groups for guided reading, the focus of experts, teacher resources, and professional development was often on what to do with the students in the small group. Only limited attention was given to what to do with the rest of the class when the teacher was working with a guided reading group. Many of us remember watching recorded guided reading model lessons at professional development sessions, where it appeared no other children were in the room at the time. The question of what to do with the rest of the kids while working with a group quickly surfaced as the most frequently asked question from educators trying to successfully implement guided reading. A decade later teachers were still asking the question (Guastello & Lenz, 2005). I am guessing that teachers are still asking that question.

Guided reading must have two critical parts. First, guided reading is defined by what is done by the teacher with the students in the small group; but secondly, and just as important, guided reading needs to clearly consider what the other students are doing when they are away from the teacher. If the latter is not thoughtfully considered and addressed, the ability to focus targeted instruction with small groups is virtually impossible. An often seen series of distractions and interruptions preclude the attention needed for successful scaffolded instruction. Even in the earliest discussions of guided reading, Mooney (1990) noted: “The teacher and children should be able to think and talk and read without being distracted by, or disturbing, the rest of the children, who will probably be engrossed in other reading and writing” (p. 57). Guastello and Lenz (2005) pointed out: “The success of guided reading as an effective instructional practice is contingent upon the implementation of a classroom structure conducive to working with the guided reading group while other students are independently and actively engaged in meaningful literacy experiences” (p. 145). Bottom line: If the work away from the teacher is not thoughtfully considered and addressed, the instructional model of guided reading is inherently flawed and probably doomed to fail.

The survey results presented in Chapter One revealed that, on average, teachers have four guided reading groups that they meet with for about 20 minutes three to four times a week. That means on any day, the students are actually away from the teacher more than they are with the teacher. On some days, some students may actually spend all their time away from the teacher. The sheer amount of independent time does concern some experts who see explicit instruction as more beneficial for most young readers and writers (Shanahan, 2014). This is why it is so critical that the time the students spend away from the teacher engages them in powerful work. One published model of rotation actually recommended that to manage guided reading groups, students would spend three out of five days away from the teacher; however, the learners all were engaged in standards-based, learner-focused “kidstations” away from the teacher (Guastello & Lenz, 2005). This is a good example of what Burkins and Croft (2010) said when they reminded teachers that independent work needs to increase the value of time away from the teacher. Otherwise, the effort to implement guided reading guarantees students will spend most of their time in unproductive ways. If that is the case, effective whole group instruction might actually lead to more productive outcomes for many or most students.

So what do we do with the rest of the kids? Historically for many classrooms, the work away from the teacher often involved completing every worksheet and workbook page recommended in the basal lesson (Durkin, 1978). Even though most programs suggest not using all the available skills sheets, teachers more often than not used every available sheet. Boushey and Moser (2006), in describing their evolution as classroom teachers, revealed that was what they used to manage their classrooms. It kept students busy so that a teacher might be able to meet with a small group. I remember as a classroom teacher rushing to school in the morning or staying late in the afternoon so I could use the copying machine to get my packet of seatwork ready for each of my students. Eventually, I began to question whether this was engaging my students in powerful work, but breaking the habit was difficult. I (1991) actually wrote the article “Worksheets Anonymous: On the Road to Recovery” to tell my story as a recovered worksheet user.

New educators would wonder what that ditto machine is in a museum. But they too need to be careful that the worksheets of the past that were replicated on a ditto machine are not simply electronically reproduced on today’s easily accessible and increasingly popular devices. My ears perked up at a recent webinar when such devices and their apps were identified as the chosen independent work even for young students. I remember reading a feature article in my local paper about the wide use of devices in one of our local elementary classrooms. Upon closer look at the color photo accompanying the story, one could see that the app being featured was a math fact sheet that looked a whole lot like the drill and practice worksheets from the past. It’s not to say that there is never a purpose for using independent seatwork, electronic or otherwise. In this chapter, we will look more closely at how to structure that work so that it retains power and leads students to make growth and solve problems.

Like Boushey and Moser’s (2006) story, learning stations or centers became the next phase of many teachers’ evolution. Guided reading programs became linked with centers and stations. Attention shifted away from what the teacher was doing at the table toward how to build effective centers and stations. In fact, some resources had very little attention to what the guided reading instruction would look like, only what the centers would look like (Diller, 2003, 2005). No matter how centers were conceptualized, they always seemed to require a lot of preparation and maintenance. Teachers’ frustration grew as the time they spent preparing or repairing the centers seldom paid off with similar levels of engagement by the students at the centers. Burkins and Croft (2010) also pointed out that the instructional density of work at the centers was often compromised for the sake of creating a place that would keep students working independently. It was difficult to create centers around what Clay called “tasks with scope” (in Burkins and Croft, 2010). These tasks are inherently differentiated because they can benefit students regardless of level (e.g., independent reading). Many called for rethinking of centers (Opitz & Ford, 2001, 2002). Over time, some experts did focus on how to create centers with instructional density, centers that could be differentiated, or centers that focused on tasks that could apply to different texts and be done at different levels. This did lessen the frustrations of some teachers, but many kept looking for other ways to engage learners.

So as the juggling acts continued—multiple guided reading groups and multiple independent learning stations—teachers looked for ways to operate more effectively and efficiently. They began to see how the implementation of different process-oriented classroom structures allowed for time to work with individuals and small groups. Teachers discovered the value of workshop approaches. Workshop approaches build in time for:

- Individual students to engage in productive work, freeing up the teacher to work with individuals and small groups.

- Daily focus lessons at the beginning of the workshop that provide common instruction that can address the needs of many students and apply to lots of different texts.

- Students to engage in reading and writing or work with their peers in partners or small groups.

- Teachers to conference with small groups and individuals while other students were productively engaged.

- Students to come back together as a community to share across their texts with each other.

Workshop approaches are whole class structures but inherently individualized. Students could work on tasks with scope like composing stories and discussing texts at different levels, which addresses the need for differentiation.

Teachers started to see that some of the small group work time that was already built into workshop structures could be positioned for guided reading instruction as well. Some promoters of comprehensive literacy frameworks (Dorn & Soffos, 2011) showed how to build layers of small group instruction and intervention around workshop structures at the heart of the literacy program. In her book More Than Guided Reading, Mere (2005) discussed her return to the use of the workshop approach to accomplish goals she thought were missing in her use of guided reading. Mere actually raised the question of whether the workshop approach should support guided reading or guided reading should support the workshop approach. Burkins and Croft (2010) asked a similar question when they wondered if all learners need guided reading, especially in an effectively run workshop approach.

While many teachers achieved the effectiveness and efficiency they were looking for when integrating guided reading with workshop approaches, some felt that the big blocks of time in which learners were expected to stay engaged in productive work were too long for young readers and writers. The workshop approaches did little to teach young students how to stay engaged during these blocks of time. That led to the fourth major way of conceptualizing work away from the teacher. Boushey and Moser (2006) popularized the teaching of routines as a way to manage learners while away from the teacher. In their Daily 5 structure, Boushey and Moser recommended teaching young children how to stay engaged in five different routines: read to self, read to someone, work on writing, work on words, and listen to reading. As students were taught each of these routines with expectations and behavioral guidelines, an intentional effort was made to help young students gradually increase their stamina so that students could self-regulate behaviors while involved in these productive routines. As stamina and engagement levels increased, the teacher found the time needed to meet with small groups for a variety of purposes, including guided reading.

In this chapter, we will revisit the answers to the question, “What do I do with the rest of my kids?” We’ll also examine what’s new to help teachers operate more effectively and efficiently when pairing work away from the teacher with work with the teacher during guided reading.

General Guidelines

Before we implement guided reading groups, let’s intentionally address what the rest of the kids will be doing when they are working away from the teacher. Let’s start with this assumption: There must be a classroom structure in place so that a teacher can work with small groups while others are purposefully engaged.

In a recent webinar focused on guided reading practices, most experts suggested investing time up front during the first few weeks of the year to build a structure that will keep learners purposefully engaged. This occurred before starting the guided reading groups. In their original description, Boushey and Moser (2006) proposed five weeks to roll out The Daily 5 structure. Richardson (2009) suggested a six-week plan to teach routines and procedures to K–1 students. Guastello and Lenz (2005) actually recommended a span of implementation time that might extend up to seven weeks. While some may question the instructional time used to build the structure, starting without a structure virtually guarantees that learners will not be engaged and the ability to attend to learners at the table will be limited. Here are ten tips to help get started in building that structure (modified from Kane, 1995):

- Tip 1: Know your curriculum.

- Whatever structure you choose, it needs to help you move students toward the learning outcomes already identified by your grade level, school, or district. The structure is not just about keeping students engaged, but also about how to help students make growth. Studying your curriculum is the one thing any teacher can and should do in advance of starting guided reading groups. Of particular interest is knowing expected entry and exit levels of learners to be able to estimate the trajectory the learners need to be on. If your guided reading is based on a “program,” then also know your program. Keep in mind your fidelity is always to your learners, but expected use of a program demands an understanding of its structure. Likewise, take time to know what specific materials you have access to in order to support learners with a variety of levels and needs.

- Tip 2: Know your learners.

- Choose a structure that fits the students who are your responsibility this year. (And they might not be the same as the ones you had last year or the ones you’ll have next year.) You have to consider what might work best for them. Producing a “ready to go” structure before knowing your students sometimes works, but often the match is not the best and leads to a lot of initial disappointment when it doesn’t work. Most veteran teachers have a good sense of the nature of the learners who will be in front of them, but we always need to be ready to adjust for a group of students who may not be the norm. The other thing to keep in mind is that one structure may not best meet the needs of all learners, so adjustments may be needed. Time invested up front in assessing learners both cognitively and affectively usually pays off in the development of a structure better suited to the needs of current students.

- Tip 3: Work with the whole class initially.

- Remember the value of gradual release models not only as a way to structure single lessons, but to also conceptualize your instruction throughout the year. The beginning of the year may be a time to exercise more control. This provides you with time to explicitly and directly teach all learners about purposes and procedures for independent activity. You can model what the activities are, why they are important, and how to do them. Then you can mediate the practice of your learners with the activities while everyone is doing the activity together, evaluating effort and reflecting on how to improve next time. Instead of just expecting learners to perform at high levels of engagement with self-regulated behaviors, whole group time at the beginning of the year allows you to actually teach learners how to perform at this level with those behaviors.

- Tip 4: Introduce the structure gradually.

- One could be too cautious in releasing the learners to operate away from the teacher. If we keep them at the carpet in the whole group until we think they have learned everything they need to know to operate away from us, they may never get off the carpet. Build learning about the structure in phases that allow the students to learn and practice part of the structure while they continue to learn other facets on how to operate productively away from the teacher. Instead of having students master five or six learning stations, different parts of the reading/writing process, or multiple routines all at the same time before trying them out, why not introduce one part and practice that to raise comfort, confidence, and competence levels before adding a new part? Get some independent activity going while you continue to teach about additional layers.

- Tip 5: Set up structure for independent use.

- Whatever structure one develops, it must be built to facilitate independent work. The activities must be achievable without the teacher’s intervention. Unless the teacher can rely on dependable outside help, the structure needs to encourage students to work individually or with each other in productive ways. Part of the rollout must include teaching for transfer. Following five critical steps should help:

- Teacher models and demonstrates

- Teacher guides the practice of the students while together

- Students practice together while the teacher monitors

- Students practice independently while the teacher monitors

- Students do monitoring themselves

- Whatever structure one develops, it must be built to facilitate independent work. The activities must be achievable without the teacher’s intervention. Unless the teacher can rely on dependable outside help, the structure needs to encourage students to work individually or with each other in productive ways. Part of the rollout must include teaching for transfer. Following five critical steps should help:

- Tip 6: Build a structure that provides accessible and authentic opportunities for engagement.

- One way to keep students engaged independently is to distinguish between compliance and engagement. In Schlechty’s book (2002) Working on the Work, he reminds us that we can achieve compliance in the students we are working with, but that falls short of authentic engagement. Compliance often happens not because the students see the work in front of them as meaningful and purposeful, but because completing the work frees them from meeting some negative consequence (passive compliance). Or maybe slightly better, completing the work gains them something they desire, like perhaps a good grade (ritual compliance). But in authentic engagement, the students are “immersed in work that has clear meaning and immediate value to them.” While there are plenty of days in which we would settle for compliance, it’s hard to see that work that has little purpose or value for students is a good way for them to spend their time away from the teacher. On the other hand, as Mooney (1990) explained, an experience that leaves the student with a satisfied feeling, motivated to continue, and expecting the next experience will be just as enjoyable is a good way for that student to spend that time.

- Tip 7: Minimize and intensify transition time.

- In observing some classrooms, it became apparent that the time it took to get all learners to where they needed to go would almost equal the amount of time the teacher would have to work with the remaining students at the table. Transition time eats into instructional time. Even a small amount of transition time adds up over the course of a school year. Wasting five minutes while transitioning from one group to the next results in a loss of 900 minutes of instructional time over a 180-day school year. Building a structure that has an efficient way for learners to check in and get started working away from the teacher is critical. Also important is building a structure that moves kids to and from the guided reading groups. Some teachers have become masterful at maximizing the use of transitional time to help learners get refreshed and refocused for the next activity. In Figure 6A, I have identified a number of ITs (intensified transitions) to avoid wasting a minute of instructional time. A quick inquiry about intensified transitions surfaces many sites. For more ideas, seek out: Noodle, Scholastic (search for “Brain Breaks: An Energizing Time-Out”), Pinterest (search for “Classroom Brain Breaks”), and Pottsgrove School District (search for “Pottsgrove School District” and “Brain Breaks” in your search engine).

- In observing some classrooms, it became apparent that the time it took to get all learners to where they needed to go would almost equal the amount of time the teacher would have to work with the remaining students at the table. Transition time eats into instructional time. Even a small amount of transition time adds up over the course of a school year. Wasting five minutes while transitioning from one group to the next results in a loss of 900 minutes of instructional time over a 180-day school year. Building a structure that has an efficient way for learners to check in and get started working away from the teacher is critical. Also important is building a structure that moves kids to and from the guided reading groups. Some teachers have become masterful at maximizing the use of transitional time to help learners get refreshed and refocused for the next activity. In Figure 6A, I have identified a number of ITs (intensified transitions) to avoid wasting a minute of instructional time. A quick inquiry about intensified transitions surfaces many sites. For more ideas, seek out: Noodle, Scholastic (search for “Brain Breaks: An Energizing Time-Out”), Pinterest (search for “Classroom Brain Breaks”), and Pottsgrove School District (search for “Pottsgrove School District” and “Brain Breaks” in your search engine).

- Tip 8: Create equally interesting activities and provide access for all learners.

- As you build your classroom structure, make sure that it doesn’t interfere with your ability to work with students individually or in small groups. Sometimes what we ask students to do independently away from the teacher is so attractive that calling someone to the table leads to groans and moans from the students. “Why do we always have to go to the table? How come we never get to work with the tablets?” Or perhaps the reverse occurs: “How come we never get to work at the table with you?” While we might need to have a lesson on the difference between what is equal and what is fair, all students should have access to high-quality and engaging learning activities. If these truly are great learning experiences for any child, then perhaps all students should have an opportunity to experience them.

- Tip 9: Focus your structure on opportunities to practice reading and writing.

- What did Mooney think the rest of the kids would be doing when she wrote about guided reading way back in 1990? “They would probably be engrossed in other reading and writing (57).” If there is one common critique of work away from the teacher, it is often that it leads to very little additional reading and writing. If the power of time away from the teacher is going to rival the time spent with the teacher, it needs to stay focused on opportunities to practice and improve on reading and writing. There are many things we can ask students to do to keep them busy, but the challenge is finding structures that keep them busy doing what they need to do most: continuing to read and write. Often the work away from the teacher resembles what some have called reading arts and crafts—response and extension projects that involve a lot of cutting, coloring, and pasting. While we know the importance of allowing students to use multiple modes, caution must be exercised to ensure that time away from the teacher engages students in what they need to practice most. Sometimes these projects create a lot of excitement about reading and writing and the ultimate outcome is more practice, but when they are just projects with no learning outcome, we might want to question their value. On the other hand, many times, if the students become excited about the reading and writing they are experiencing, they will self-initiate projects that allow them to respond to and extend the work they are doing.

- Tip 10: Always be ready to go back and re-examine structure.

- Just as we need patience to build the structure in the beginning of the year, we also need to have patience in allowing the structure to work. We need to avoid the urge to abandon our efforts too early or too fast. There is nothing wrong with stepping back from our concerns about implementation and reflecting on how to address those concerns. Re-teaching through more modeling or guided practice is sometimes warranted. It is certainly better than tossing out a structure that already consumed a lot of time, energy, and effort to put in place.

Figure 6A: Intensified Transitions

- Sing a transition song to help students move. (See Supporting Transitions in the Appendix.)

- Conduct a calming down routine. (See Supporting Transitions in the Appendix.)

- Integrate a socializing moment. (See Supporting Transitions in the Appendix.)

- Perform an action song or chant as students move.

- Recite a familiar poem as students move. (See “Miss Hocket” Poem.)

- Dramatize a way to move (tiptoes, slow motion, shuffle).

- Count in a variety of ways (by twos, by fives, backward, filling in skipped numbers).

- Spell out words in a variety of ways (by chunks, backward, no vowels).

- Re-energize through a quick exercise that children do in place.

- Invite visualization through an imagined scenario (beach scene, top of the mountain, cloud watching).

- Play “Teacher Says” (like “Simon Says,” but guide toward the next activity).

Structures for Engagement Away from the Teacher

So what’s new, and what’s next in answering the question—what do I do with the rest of the kids? Let’s look at the four typical ways of answering this question.

Structure One: Routines

When asked what’s new with independent work, we would have to start to look at routines. We have finally learned that no matter what structure a teacher creates to surround guided reading groups, students have to be able to stay engaged in meaningful activities for sustained periods of time. That is true whether the activity is within a workshop framework, at a learning station, or at the student’s desk or table.

We have learned a lot about the value of routines and how to teach them from Boushey and Moser (2006, 2014). Since the publication of their popular text The Daily 5, routines have been moved to center stage for many classrooms. They described The Daily 5 as a management system that focuses on teaching students to sustain levels of engagement in five basic routines: reading to self, reading to someone, listening to reading, working on writing, and working with words. What was new in their approach? First they reminded us there is a difference between expecting behaviors and teaching students how to behave. Setting and conveying high expectations that students will be able to perform reading and writing activities can contribute to student learning. But that is only true when combined with other conditions of language learning (Cambourne, 1995, 2001). Those expectations are critical because thinking one can and wanting to succeed are starting points for motivation and engagement. (See pages 58–59 in Chapter Three for a complete list of Cambourne’s conditions.) If learners are to find joy in their efforts, knowing an important adult thinks and wants them to succeed can be huge (Opitz & Ford, 2014). But thinking one can and wanting to succeed also means the learner knows how, and that is where teaching behaviors comes into play.

Secondly, Boushey and Moser (2006, 2014) point out there is also a critical difference between managing student behaviors and teaching students to manage their own behaviors. Management often suggests an external source that is present to monitor the behaviors. In a recent classroom visit, I observed a masterful teacher who was using a newly embraced management system in which she had been trained. It required pre- identifying a short list of behaviors (e.g., working quietly and staying in one place) that were going to be monitored individually or in groups during the next learning period with identification of consequences and rewards up front. In the end, there seemed to be as much attention to the monitoring of behaviors as there was to monitoring student learning. I wasn’t convinced students were learning how to manage their own behaviors with such a heavy-handed, teacher-driven system. My guess is the teacher will still need to do the monitoring during the guided reading instruction.

So what routines should we teach students so they can work independently and productively while the teacher works with the guided reading group? Based on the guidelines presented, being able to read on your own often goes to the top of the list. Some caution: “Reading to self is important, but it is not as effective as reading communally with a teacher and classmates. Schools should teach reading and encourage and enable students to engage in reading beyond school” (Shanahan, November 12, 2012). Others challenge that notion and make a case for the need for students to engage in independent reading programs (Morgan, Mraz, Padak & Rasinski, 2009; Allington, 2013). And what else would be on the list? Reading to someone might have just as much value, with listening to reading close behind. In fact, if students could engage in just those three behaviors for significant periods of time, most teachers would be happy. Similarly, being able to work independently on writing would be another critical routine that would contribute to improving literacy performances. Finally, word study can keep students engaged as they explore multiple dimensions of words in fun and informative ways. Figure 6B includes helpful routines we have discovered, using published resources such as The Daily 5 as a guide.

Figure 6B: Tips for Improving Routines

- Read to Self

- Tips for Planning: It’s easy to teach students what this should look like externally (get started right away, read quietly, stay in one place, etc.), but do young children really know what they are supposed to do? You might conduct a simple interview (Opitz & Ford, 2015) with readers to see if they understand what silent reading is:

- When someone tells you to read silently, what do you think you are supposed to do?

- What do you actually do when you read silently? What happens inside your head?

- How is silent reading different from oral reading?

- Do you like to read silently? Why or why not?

- Tips for Materials: When teaching the three ways to read (read the picture, retell the story, and read the words), wordless picture books are a great tool as they help teach the need for reading the pictures. Since these can be quite sophisticated, all students can use books like these for improving their visual literacy. Picture books with minimal pictures are the best way to teach the importance of reading words. The Book With No Pictures by B.J. Novak (Dial) or We Are in a Book! by Mo Willems (Disney-Hyperion) are good options. Telling the story as a way of reading is easily modeled with familiar fairy tales and folktales. Check out The Ant and the Grasshopper, Beauty and the Beast, and The Boy Who Cried Wolf (Capstone Classroom). I Hate Reading by Arthur and Henry Bacon (Pixel Titles) is a great book to use to point out the difference between pretending to read and actually reading.

- Tips for Instruction: Make sure the students are actually reading appropriate texts at increasingly complex levels. Consider your goal. Independent-level texts may build comfort, confidence, and automaticity. Instructional-level texts may allow for problem-solving at the word and text levels that leads to cognitive growth. Even a frustrational-level text can have a purpose. You can position it as the student’s goal book or dream book, and revisiting the harder text can show the student how he or she is improving over time. All types might be in the readers’ baskets, boxes, or folders but make sure readers know which books are best for which purpose and goal.

- Tips for Planning: It’s easy to teach students what this should look like externally (get started right away, read quietly, stay in one place, etc.), but do young children really know what they are supposed to do? You might conduct a simple interview (Opitz & Ford, 2015) with readers to see if they understand what silent reading is:

- Reading to Someone

- Tips for Planning: Preparing for performance is a good authentic reason to read with someone. Plan to teach a step-by-step approach to guide learners to work together for that outcome:

- Leader reads the story aloud;

- Both chorally read the story together;

- Choose parts;

- Practice parts on own;

- Practice parts together; and

- Be ready to share.

- Tips for Materials: Look for multi-level texts. Poetry anthologies allow readers at different levels to find verses at their levels. Scripts allow for the assigning of different parts. Many informational texts have features at different reading levels. Journalistic texts also have easy and hard parts. Cumulative tales are also good because the strong reader can introduce the new line and the partner can repeat the familiar lines.

- Tips for Instruction: Training buddies to be coaches is critical. The suggested lesson of “How to Be a Good Reading Coach” needs to be emphasized. Partners that learn how to wait and let their friend work out the right answers or know how to make strategic suggestions without giving answers will lead their friend to greater growth and may learn more about the process themselves.

- Tips for Planning: Preparing for performance is a good authentic reason to read with someone. Plan to teach a step-by-step approach to guide learners to work together for that outcome:

- Listen to Reading

- Tips for Planning: You can lengthen engagement levels in listening routines by planning to teach steps in listening to a recorded story:

- Listen to the story and follow along;

- Listen to the story and read along;

- Turn off the story and read by yourself;

- Listen to the story and read along again. Watch for parts you found tricky;

- Turn off the story and read the story again to see if you can improve.

- Tips for Materials: Digital texts may be the easiest way to set this up. Check out Unite for Literacy online for digital books. The easily accessible texts are free and available in nine languages.

- Tips for Instruction: Listening to a story may free up some readers to focus more on meaning making, so consider holding students accountable during this routine by introducing ways to respond. This can prepare them as they move to responding during silent reading.

- Tips for Planning: You can lengthen engagement levels in listening routines by planning to teach steps in listening to a recorded story:

- Work on Writing

- Tips for Planning: Students should begin to see their reading materials as mentor texts of good writing. Plan to show students examples of good writing when it appears in their reading materials. Also plan for lessons that relate to writing, whether in response to reading or to mirror the author’s craft under discussion.

- Tips for Materials: Refer to your read-alouds during focus lessons for different types and purposes of writing [Written Anything Good Lately? by Susan Allen and Jane Lindaman (Millbrook Press)], formats [(I Wanna Iguana Karen Kaufman Orloff (Putnam) and Diary of a Worm by Doreen Cronin (HarperCollins)], different traits [(Voices in the Park by Anthony Browne (DK Children)], or mechanics [(Punctuation Takes a Vacation and other books by Robin Pulver (Holiday House)]

- Tips for Instruction: Writing instruction is critical. The lessons need to focus on what your learners need. Don’t do a mini-lesson because a writing lesson is scheduled. Keep your focus on what your students need to learn as writers. Remember, any text they have created can also be the focus when you confer with the student. Then you can assess both reading and writing at the same time.

- Word Work

- Tips for Planning: Plan word work around key strategies. Make sure word work is appropriate for the readers: emergent (concepts of print, alphabetic knowledge, phonemic awareness), early (phonics, sight words, structural analysis, context clues), transitional and fluent (word meanings). Then match the word learning opportunity to the outcome.

- Tips for Materials: Provide access through read-alouds, shared readings, and displays to books that create interest in or have fun with words. How about Double Trouble in Walla Walla by Andrew Clements (21st Century), Cat Tale by Michael Hall (Greenwillow), or the Fancy Nancy series by Jane O’Connor (HarperCollins)? Add riddle and pun books to the collection. Look for series from Marvin Terban, Brian P. Cleary, and Ruth Heller.

- Tips for Instruction: If you are already using an approach for learning about words (i.e., Words Their Way), bring that approach into your routine. You do not need to set up additional word work just for the sake of creating this routine.

So what’s next in independent work through routines? It seems obvious, but it might be connecting routines more closely to learner outcomes. One recent critique of routines by Shanahan (2014, November 12) suggested that the routines are too focused on doing activities:

“The Daily 5 establishes a very low standard for teaching by emphasizing activities over outcomes, and by not specifying quality or difficulty levels for student performances. Teachers can successfully fulfill The Daily 5 specifications without necessarily reaching, or even addressing, the standards…. There are lots of ways to a goal, and I deeply respect the teacher who has a clear conception of what she is trying to accomplish and the choices that entails. Starting with the activity instead of the outcome, however, allows someone to look like a teacher without having to be one.”

Most critiques of any program are often based on the way the programs are interpreted and implemented. Many would suggest that this is really a critique of a poor implementation of one program. Again, published programs like The Daily 5 are management structures. Their content can be driven in many purposeful ways to address stated concerns.

So how would goal-oriented routines look? Shanahan (2014, May 24) identifies four critical goals: word learning, oral reading fluency, writing, and reading comprehension. He reluctantly adds one affective goal (love of reading and writing). Now imagine if the launching lessons were focused on goals, why each was important, what you can do to improve in each area, and how you would know if you are making progress. (See Figure 6C.) The daily conversation would revolve around discussion like these:

- Tell me what goal area you are going to work on.

- Tell me what “I can” statement in that goal area you are working toward.

- Tell me what you are going to do to make progress toward your goal.

- Tell me how you are going to know if you made progress.

- Is there anything you need from me to get started?

I will just point out, however, that this conversation does sound a lot like the conversations recommended by Boushey and Moser (2009).

Figure 6C: Goal-oriented Launching Lesson

- “I can” statement

- I can quickly read the 100 most common words without a mistake.

- Why I want to accomplish this goal?

- It will help me read more smoothly and quickly. If I am not stopping to figure out these words, I can focus more on meaning when I am reading or writing.

- How I can accomplish this goal?

- I can work on learning these words by using Look-Say-Write-Check.

- I can play flash card games with my buddy.

- I can use a sight word app on a tablet.

- I can record myself saying the words and listen to see how many I got right and how fast I went.

- I can read some books from the sight word basket.

- I can look back at my writing to find sight words and see if they were right.

- How I will know that I am meeting my goal?

- I will work with a partner who will check and time me as I work through the list of words. He or she will help me count how many I got right and how fast I went. I will record this on my chart.

So what else is next in independent work based on routines? Freebody and Luke (1990) provide another framework by which we can move the use of routines forward and perhaps in a direction that might be more appropriate with older learners. Freebody and Luke’s Four Resources Model emerged in the 1990s to broaden our view of what reading means in a multimodal world in which sign systems include print but other auditory and visual systems as well. Think about how music, visual graphics, photographs, or oral speeches are “read” or interpreted. Freebody and Luke define literacy in terms of a repertoire of capabilities: able to decode written text, understand and compose meaningful texts, use texts functionally, and analyze texts critically. All four are of equal importance, especially since readers usually engage in several at the same time.

The five routines in The Daily 5 are primarily presented as opportunities for code breaking and meaning making. They often seem to be ends in and of themselves. Freebody and Luke also remind us of the importance of promoting the roles of text users and text critics. For text users, the functional use of reading and writing for a purpose is emphasized. One such function is to learn about something else, encouraging learners to engage in meaningful inquiry that could increase content knowledge and reading and writing performance. Another way to move these routines to a means toward ends versus ends in and of themselves is to focus on performance. Entertaining others can be another powerful way to help students purposefully use the texts they are consuming and creating.

So what would launching lessons looks like for text users? Let’s look at teaching students how to engage in independent routines related to inquiry and performance following five key steps. Figure 6D illustrates specific launching lessons.

Figure 6D: Specific Launching Lessons

- Step One: Catalyst

- Description:

- Metaphorically start a fire in our learners. Make the routine so attractive that the students will naturally gravitate toward it. Create a sense of joyful effort so they are chomping at the bit as soon as we step out of the way.

- Inquiry:

- Share the texts that celebrate inquiry and learning like Me… Jane by Patrick McDonnell (Little, Brown) for younger children or The Island by Gary Paulsen (Scholastic) for older learners.

- Flood the room with related informational texts about a topic to generate interest and questions about a topic. Link these to topics being explored in social studies and science.

- Seize multimedia reports on a current event to surface questions worthy of future exploration.

- Performance:

- Share the texts that celebrate performance like ZooZical by Judy Sierra (Knopf) or The School Play from the Black Lagoon by Mike Thaler (Scholastic).

- Flood the room with performance materials—scripts, lyrics, speeches—to generate interest and start the planning process.

- Seize the viewing of a live or recorded performance to encourage something similar in class.

- Description:

- Step Two: Life Applications

- Description:

- Make sure that the question of why this is important in the real world—not just the school world—is so obvious that the question of why we have to do this doesn’t surface.

- Inquiry:

- Discuss situations inside and outside of school when a student could use inquiry processes and procedures—from purchasing decisions to developing persuasive arguments in influencing family members.

- Performance:

- Brainstorm careers in which oral performance is valuable—from obvious roles like actors and media reporters to less obvious roles like teachers.

- Description:

- Step Three: Learning Goals (How is your reading, writing, thinking going to improve?)

- Description:

- Link the routine to specific goals in reading, writing, and content so students can see how pursuing the routine also helps them get stronger in those academic areas.

- Inquiry:

- Help students identify specific goals during the inquiry process. Examples might include:

- I can grow in my ability to read different types of nonfiction texts.

- I can grow in my ability to write an informational text.

- I can improve my ability to use presentations to persuade others.

- Help students identify specific goals during the inquiry process. Examples might include:

- Performance:

- Help students identify specific goals to improve in their performance skills. Examples might include:

- I can improve my ability to use pacing, pitch, and volume to perform dialogues.

- I can better use visualization strategies to conceptualize what is needed (props, costumes, visual aids, scenes) to support the oral performance.

- I can better use physical movements (gestures, body language, dance) to enhance my oral performance.

- Help students identify specific goals to improve in their performance skills. Examples might include:

- Description:

- Step Four: Procedures

- Description:

- Provide a step-by-step process that provides students with intentional directions on how to carry out the routine. They should not be so inflexible that the learners cannot return to or revisit steps when new ideas emerge or original ideas are rethought.

- Inquiry:

- Focus class time on the procedures involved in inquiry:

- Generate ideas and questions.

- Make a plan to collect information.

- Organize and synthesize information.

- Draw conclusions.

- Develop presentation.

- Deliver presentation.

- Remember to use outside time to watch related digital media, create models, try out simulations, conduct the experiments, produce the presentation, etc.

- Focus class time on the procedures involved in inquiry:

- Description:

- Performance:

- Prepare script and select a mode (live, electronic, multimedia performance).

- Practice the script.

- Choose parts and tasks.

- Practice parts independently and complete individual tasks.

- Put all parts and tasks together.

- Focus class time on rehearsal for the performances.

- Select or create a script for the oral performance.

- Assign parts to practice independently.

- Assist each other in rehearsing to improve vocal features and physical movements to enhance performance.

- Make decisions about needed visual supports.

- Collectively rehearse together, coordinating efforts across involved students with final supports.

- Deliver performance.

- Remember to use outside time to create costumes, props, scenery, animations, etc.

- Step Five: Problem-solving

- Description:

- Anticipate and address typical problems that may occur in working through the routine, so solutions have been discussed and students can continue to operate away from the teacher.

- Inquiry:

- Discuss any potential areas of conflict and agree up front about solutions, including:

- Limits on resources, supplies, and materials available to support the inquiry

- Constraints on time available for inquiry and setting deadlines

- A conflict-resolution technique agreed upon by the group (majority vote, random choice by flipping coin, etc.)

- The teacher’s role in the process, remembering that time is needed to work with guided reading groups

- Discuss any remaining issues with students prior to starting the process or allow for future discussions

- Discuss any potential areas of conflict and agree up front about solutions, including:

- Performance:

- Discuss any potential areas of conflict and agree up front about solutions, including:

- Limits on resources, supplies, and materials available to support the performance

- Constraints on time available and conducting the performance

- A conflict-resolution technique agreed upon by the group (majority vote, random choice by flipping coin, etc.)

- The teacher’s role in the process, remembering that time is needed to work with guided reading groups

- Discuss any remaining issues with students prior to starting the process or allow for future discussions

- Discuss any potential areas of conflict and agree up front about solutions, including:

- Description:

Structure Two: Workshop Framework

Workshop frameworks provide an inherent structure that engages students in authentic individual and peer reading and writing experiences with potential to free the teacher to conduct guided reading sessions. Because of this, some (Dorn & Soffos, 2011) have placed one or more workshops at the heart of their literacy frameworks. In the national survey of guided reading practices, almost one-third of teachers reported that they had already paired guided reading groups with reader’s/writer’s workshop.

Structurally, the workshop framework is fairly simple in its conceptualization. The workshop typically begins with universal instruction. Often called a mini-lesson—though some prefer calling it a focus lesson since “mini” may make it seem less important. This explicit instruction provided by the teacher, usually in a large group setting for all students, is determined by curriculum demands and student needs in reading and writing. The instruction is very targeted and designed to occur in a relatively short amount of time, usually no longer than 10–15 minutes.

Universal instruction is followed by a quick check-in on the class. Atwell (1998) calls it taking a “status of the class” (p. 107). Without losing too much instructional time, the teacher sets the purpose for the independent and peer work that is to follow. Students quickly state what they will be doing during the independent time. A quick transition is made by the students to their independent reading and writing activities, with the teacher freed to begin work with identified students in guided reading. Identifying those students first often allows them to transition and be ready at the table by the time the teacher has checked in with the remaining students. Teachers may want to invest in check-in systems that identify and remind students where they are at in the process.

This leads to the heart of the workshop framework: significant uninterrupted time to engage in sustained reading and writing. The longer the students can stay productively engaged during this part of the workshop, the more opportunities the teacher has to meet with guided reading groups. If the typical guided reading group is about 20 minutes in length, one can see that as a minimum amount of time for sustained reading and writing. As previously stated, developing readers and writers to stay engaged for that amount of time begins with focusing on teaching those routines and their required behaviors. To be able to meet with two guided reading groups, the amount of needed time doubles. The expectation of some students to sustain their work for 40 minutes probably starts to push the boundaries of what can be expected in elementary literacy programs. It was this large amount of sustained activity expected by the workshop framework that caused Boushey and Moser to propose The Daily 5 as an alternative. This would break up time into smaller chunks that are more compatible with the learning characteristics of younger children.

It should be noted that students do not need to be restricted to just large amounts of sustained independent reading and writing during this part of the workshop framework. Students can also be taught how to work together so that peer partner and small group work can also help to keep students engaged. As students move through the drafting, revision, and editing phases of writing, they can be taught procedures that help them work with each other on their writing. As students read the same topic across texts, they can be taught procedures on how to help each other make sense of the materials they are reading. They can be taught how to meet away from the teacher to discuss what they are reading, thinking, and learning with each other. This part of the workshop can be like a studio in which participants are working individually and with others at various stages in the process. This vision of the workshop may make longer periods of engagement seem more possible than long periods of sustained silent reading and writing.

Another way to address the long period of needed self-engagement by students is to spend just a few minutes between two guided reading groups to recheck the status of the class. As the groups transition to and from the table for guided reading instruction, take a minute to check in on learners. In some programs, a mid-workshop lesson is conducted quickly based on something students were successfully doing, or intervening occurs to help students who are struggling. If needed, Boushey and Moser are not alone in recommending a little brain break to get everyone refocused, re-energized, and ready to stay engaged for another block of time. Examples of brain breaks are listed in Figure 6A.

The workshop framework usually ends with a few minutes set aside to bring the class back together for sharing. This sharing time serves so many purposes. Having time to share what was read, written, and learned makes the time set aside for reading, writing, and learning more purposeful. It actually contributes to higher levels of engagement. Public sharing allows the teacher to drop in on students and the work they did, which would be hard to observe while engaged in guided reading lessons. It allows the class to reflect on not just what was learned but how they are doing in meeting their goals. Finally coming back together at the end allows the teacher to rebuild the classroom community and create a culture of collaboration and celebration that permeates long after that moment in time. To eliminate this sharing time actually works against the workshop activity that precedes it and the workshop model as a whole.

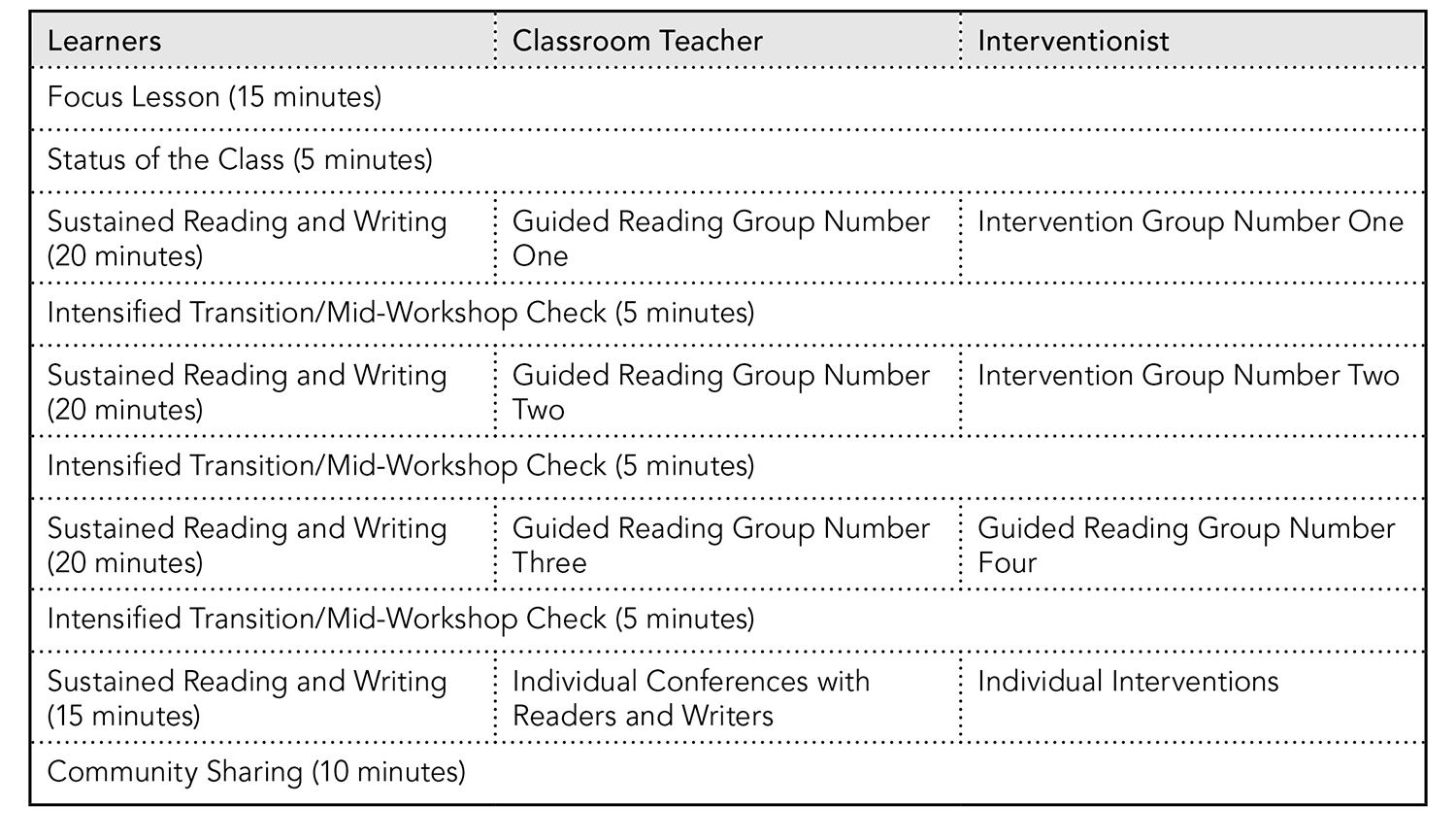

With a longer block or another professional in the room, more guided reading can be added to the program. (See Figure 6E.) Blocks can also accommodate time allocated to specialists outside the classroom. You can reach closure on one part of the block and resume the work on the next part of the block when you return to the classroom.

One thing to remember is that guided reading is focused on scaffolded instruction for reading. Writing might be used as a tool to see what students know about print or as a vehicle to share how meaning was made through written response, but guided reading lessons typically do not provide scaffolded instruction in the composing process. Helping students become better writers will require the integration of small group writing conferences.

Figure 6E:

Workshop Alignment (90-minute Block)

Workshop Alignment (120-minute Block)

Structure Three: Learning Stations

So what are students doing when they are not working directly with the teacher? The national survey indicated that almost three-fourths of the teachers paired their guided reading with centers. When we look at what were the most frequently used centers, they looked a lot like the routines we previously listed as important.

- Listening center

- Writing center

- Working with words centers

- Reading center

- Buddy reading center

As we stated, these centers will still require students to stay engaged for sustained periods of time. They often represent physical locations that include supplies and resources needed.

So what could I say about centers that hasn’t been said by others? Lists of center ideas offered by others look more alike than different. For young students, Richardson (2009) offered these work station possibilities: book boxes, buddy reading, writing, reader’s theater, timed reading, poems and songs, ABC/word study, word wall, reading the room (word hunts), oral retelling, listening, computer, overhead projector, geography, science, big books, and library. Lists like these seem to be a mix of materials, equipment, activities, and routines. But they are mostly lists of things students can do. They often are not defined as things students need to do or should be doing; rather, they are things that will keep students busy. The goal for Richardson seems to be to make sure the students can stay busy with a work station for at least 20 minutes. For intermediate students, she focuses on four activities that seem to be more purposeful: buddy reading, word study, vocabulary, and writing, but they also seem to be goal free with menus of options.

Diller (2003) provided some of the most comprehensive ways to conceptualize centers, or what she called “literacy work stations,”: “an area within the classroom where students work alone or interact with one another, using instructional materials to explore and expand their literacy. It is a place where a variety of activities reinforces and/or extends learning, often without the assistance of the classroom teacher. It is a time for children to practice reading, writing, speaking and listening, and working with letters and words” (pp. 2–3). Diller is clear to point out that literacy work stations are set up for the entire year with the materials changed to reflect different levels, strategies, and topics. She also reminds us that the materials need to be differentiated for different students at different levels. They are not just things to do, but places to go to independently practice what has already been taught. In her book for teachers of young students (Diller, 2003), she identifies six major work stations: classroom library, big book, writing, drama, ABC/word work, and poetry. She adds nine additional possible work stations: computer, listening, puzzles and games, buddy reading, overhead projector, pocket chart, science, social studies, and handwriting. In the end, there are a lot of ideas, but it becomes hard to see how you create a system to engage learners that requires setting up at least six major centers, supplying each with the materials needed to meet the needs of diverse learners, introducing them so each learner knows what to do at each station, and then monitoring them so that each learner does what they need to do at each center.

Her book for teachers of older learners (Diller, 2005) does include how literacy work stations can be positioned to support goals in comprehension, fluency, phonics, and vocabulary. But again, positioning nine centers to provide independent practice for a diverse group of learners in four critical areas and making sure that happens only shows the complexity of using work stations to partner with guided reading.

Maybe the more critical discussion is not about what can be a center but about how we get more power, value, and mileage from centers or stations. Figure 6F offers some suggestions of things to remember and things to avoid.

Figure 6F: Center Suggestions

- Remember to…

- Create centers that are destinations for ongoing activities with an inherently individualized scope, such as a reading corner with access to resources and support or writing centers with tools, mentor texts, and reference resources.

- Allow spaces and tools used for large group and shared experiences to be accessible as centers where students can repeat instructional experiences that the teacher has modeled. Let students revisit whiteboard experiences, the shared reading big book, the pocket chart, or the word wall.

- Let students be involved in the organizing and decorating of the center spaces. Let their work and class-generated products that flow naturally from instruction provide the backdrop for the center.

- Invest in a visual display where students can independently check into centers so that a quick glance allows you to know who should be where.

- Set up a way for students to record how they spent their time, including what goals they were working on (contracts, punch cards, learner notebooks).

- Have students take responsibility for straightening up the centers on a regular basis after use. Different teams of students can be assigned to different centers.

- Teach and trust them to do what needs to be done to leave the center in good condition.

- Process students’ learning at the end of the language arts block. Focus on what was learned not what was done: What did you learn today? What did you do to become a better reader? Writer? What would help your learning the next time you work at the centers? (Diller, 2005)

- Avoid…

- Creating centers that require the completion of an activity, leaving the center in need of frequent changing with little possibility of transcending texts, task, and learners.

- Restricting student use of instructional spaces and tools that could provide purposeful goal-oriented practice for the sake of “protecting” the areas or materials.

- Assuming that you can’t teach students how to use these areas and trust that they will once taught.

- Spending significant amounts of time and/or resources to create “beautiful” spaces.

- Spending your time planning instruction and analyzing assessments.

- Being distracted to constantly monitor which students are at the right centers.

- Implementing a heavy-handed, teacher-directed monitoring system that requires time to keep track of what students have done and learned.

- Seeing the cleaning up of centers as your responsibility.

- Thinking that you can’t teach and trust students how to clean up each area.

- Ending the learning when the centers end.

- Focusing sharing on what was not learned or completed.

Structure Four: Independent Seatwork

So what is next in seatwork? If the worksheets and the workbook pages of the past disappear, and we avoid replacing them with electronic versions of the same thing, is there any place for seatwork?

For me, the best seatwork offers opportunity to practice skills and strategies as students continue to work on growing as readers and writers. Assuming that much of that time at one’s seat or table will be spent reading independently and working on writing, other activities could provide more targeted practice. Those activities would evolve naturally from instruction that has taken place in the large or small group, be self-generating, be easily accessible, and provide more purposeful ways to practice.

In my classroom, the best way to create that type of seatwork was through the use of poems. Poetry had a pervasive place in my classroom. Friendly and familiar poems that had been introduced through shared reading experiences became tools for additional practice. My students kept a poetry folder. It provided easy access to texts for practice. For each poem that had been shared in the class, purposeful practice materials were generated for the poetry folder. As an example, I will use one of our favorite poems: an anonymous limerick called “Miss Hocket”:

A young kangaroo named Miss Hocket

Carried dynamite sticks in her pocket

By mistake, a match

Dropped into her hatch

And Miss Hocket took off like a rocket.

For a little physical exercise, my class loved to crouch in the kangaroo position and jump up when Miss Hocket took off like a rocket.

Here’s how the folder evolved:

- A hard copy of the poem was given to each student, allowing for repeated readings of the poem individually and with partners. In the large group, a variety of techniques were used to model how to set a poem up for a choral reading or reader’s theater performance. Rasinski (2003) identified eight ways to do choral reading: refrain, line-a-child, dialogue, antiphonal reading, call and response, cumulative, choral singing, and impromptu choral reading. You can build in poetry breaks throughout your day by inviting individuals and partners who are ready to perform a chance to share. Poetry breaks are a good way to intensify transitional time.

- A word list was created from the vocabulary in each poem or from a part of a longer poem. Students were invited to work on improving their automaticity in saying the words. They could time themselves or each other. The list was numbered, and ways of having fun with the numbered lists were modeled in the large group. These included calling out a word and having your partner call out the number next to it, or just the reverse: calling out a number and saying the word next to it. (See Figure 6G.)

- Word cards are created for the folder by the student. Students are given a grid (different colors for different poems) on which they write each word from the poem or part of the longer poem in one box on the grid. (See Figure 6H.) The words are cut apart to form a set of cards that can be used in a number of individual or partner activities, which have been modeled in the large group. These might include word sorts, matching games, modified card games (e.g., “War”—longest word wins), rebuilding the poems, rearranging the cards to make new sentences, and other variations. (Tip: Have students put their initials on the back of each card so they can be separated as needed. Give each student a plastic bag when new cards are made.)

- Each poem did lead to a product that could promote more reading and writing. With “Miss Hocket,” students were given individual pages with one line from the poem on each page. Illustrating and sequencing the pages led to the creation of a self-illustrated book. Since all students created their own version, the class ended up with multiple sets of the book to use in independent, partner, and small group reading forums. (See Figure 6I.)

Figure 6G: Word List for “Miss Hocket”

- a

- and

- by

- carried

- dropped

- dynamite

- hatch

- her

- Hocket

- in

- into

- like

- kangaroo

- match

- Miss

- mistake

- named

- off

- rocket

- sticks

- took

- young

Figure 6H: Word Cards for “Miss Hocket”

Figure 6I: Self-Illustrated Page

Any poem that is shared and learned as a part of large group instruction can lead to similar activities. As new poems are learned and new activities introduced, students can rotate them into their folders and “retire” older activities by taking them home. There will always be something in the poetry folder that the student can work on while waiting for a turn at the guided reading table. Teachers may find the compilation of the “12 Best Poetry Websites for Kids” from EdTech a good source for additional poems and activities, especially Giggle Poetry and Kenn Nesbitt’s Poetry4Kids.

Teachers can look for other self-generating, easily accessible, purposeful ways to practice reading and writing. For example, in The Fluent Reader, Rasinski (2003) identified a number of classroom procedures that help capture the power of repetition, providing reading practice with purpose so students don’t easily tire of their texts. These include procedures that can start with the teacher in shared reading, guided reading, or individual reading conferences and can be continued or replicated by the student as independent or partner activities at their desks or tables: formal repeated reading, radio reading, corrective repeated reading, oral recitation lessons, fluency development lessons, and phrased text lessons.

What’s Next?

In this chapter, I have tried to make the case that what is done away from the teacher needs to rival the value of the instruction received during guided reading. Not only does the teacher need to be able to operate without interruptions to effectively target instruction for the learners at the table, but the students need to be able to independently use their time away from the teacher to gain greater growth. As guided reading moves toward the future, the clear challenge for teachers is to create independent learning opportunities that are goal oriented and growth focused for students. To simply provide a menu of options students can do when they are not working with the teacher may keep many busy and lead to improvements, but in the end we must be more intentional. We must be able to demonstrate that those activities are also leading students toward becoming proficient readers and writers. Doing the activity and staying busy cannot be an end in and of itself. We need independent work that leaves the learner satisfied, wanting more, and motivated to try again so that growth continues and proficiency is achieved.