Meet Hallie.

She works for a large company in a large office—work she loves—and like so many of us, she is consigned to a desk for the greater part of every workday. Atop her desk is a bank of computer monitors on which Hallie tracks and manages a range of projects, procedures, and operational activities. She does it all sitting down, although often on the very edge of her high-tech, lumbar-supported, mesh-backed, spongy-seat office chair, as she peers with acute concentration at first one screen, then another. Hallie typically rests her elbows or forearms on the desk or her lap, and her hands and wrists on her computer keyboard. Her body’s spine is curved toward her work, and her head juts forward as if it wanted to be ready to meet the next piece of vital information head-on.

It’s a common posture for people who work in offices, and here’s what it does to Hallie—and to you, if you’re in a similar situation.

Since her legs don’t have to hold her up, Hallie’s lower back does the job instead, becoming the weight-bearing center of her body, which is not what the lower back was designed to be. She feels the consequences of that discrepancy in a recurring back pain, which is getting worse. She also feels tension in her neck, no doubt because her normal workday posture thrusts her head so far forward that she overextends and stresses her neck muscles.

It’s called anterior head carriage (sometimes also known as lollipop head), and while it may have looked good on Queen Nefertiti in the famous bust in the Neues Museum in Berlin—of course, Nefertiti’s head had to hold up the enormous, elongated crown of Egypt—it’s really a shortening of the muscles at the back of the skull, the occiput, in a misalignment that strains the neck. No wonder Hallie longs for a masseur to knead the back of her neck at the end of every workday. She suffers from headaches too, and she routinely takes aspirin or ibuprofen to alleviate them.

But these standard, garden-variety aches and pains—after all, 80 percent of American adults complain of back pain—are just the beginning of what’s happening to Hallie, the tip of an iceberg of disasters that derive from the simple fact that in the life she lives, resisting gravity is something she does rarely and in minor ways, even though her body is built to resist gravity repeatedly and in myriad ways.

Because Hallie does not resist gravity sufficiently, gravity compresses her. The muscles constructed to keep her upright against gravity have weakened from lack of use; the joints taking the pressure the muscles should absorb have grown rigid. That’s backward from the way things should work, leaving Hallie with weak muscles and stiff joints—the exact opposite of what they should be.

As a result, Hallie’s chest droops downward under the force of gravity, taking her ribcage with it and pressing the ribcage into her pelvis, thereby shortening her torso and further bending the muscles of her lower back out of shape. Inside this drooping structure, everything gets squashed, flattened, jammed together in a body that is pressed forward, collapsed inward, squeezed down, out of alignment, and off-balance. That’s what compression by gravity does, and it is the daily condition of Hallie’s life.

The consequences of this compression—apart from the aches and pains in Hallie’s back, neck, and head? They influence every system, process, and function of her physiology.

Start with her breathing. Hallie’s lungs—everybody’s lungs—are protected by the ribcage, which, powered by the muscles around it, expands and contracts to make breathing happen. Compress the ribcage and the muscles around it cannot expand and contract to the full—and neither can the lungs. Hallie’s breathing is diminished: less oxygen in, less carbon dioxide out, and too much residual stuff left over in the lower lobes of the lungs.

Impeded breathing, of course, shortchanges everything else. It can disrupt or obstruct any or all of the functions and activities Hallie’s organs are there to carry out; such disruptions are at the heart of most of the chronic illnesses that plague us today. It can slow Hallie’s metabolism. It can create a self-perpetuating pattern of pain. Moreover, respiration is at the root of immunity; cheat your breathing and you cheat your body’s ability to protect itself from toxic influences. Hallie gets a lot of colds.

Compression that squashes Hallie’s torso affects her digestion too. For one thing, it reduces the space available for the digestive process and therefore for the body’s ability to obtain nourishment from what she eats. It also affects the enteric nervous system, the body’s so-called second brain, or brain in the gut, that part of the central nervous system that resides in and controls the gastrointestinal system and, with its network of neurotransmitters, sends and receives messages to and from all parts of the body. This second brain also serves a major role in Hallie’s sense of well-being, and it is not uncommon for Hallie to feel out of sorts in general and to attribute it to what she refers to as “a nervous stomach.”

Compression affects her posterior chain of muscles—consisting of her aching lower back muscles, the gluteal muscles of the butt she tries to keep taut through marathon Spinning bike sessions, and the hamstrings and calves that routinely dangle beneath her fashionable desk chair. Compression of this posterior chain causes a breakdown of movement that snowballs across Hallie’s body, for these are the muscles that transfer force so you can move your body forward and, by the same token, keep it upright and stable. Precisely because she sits all day and therefore is not activating the posterior chain to do what it was built to do, Hallie is at a mechanical disadvantage when she needs the muscles for forward movement, or for stability, or for being upright. That mechanical disadvantage has made it almost impossible for Hallie to lift her young son anymore; the muscles for that are effectively out of action through lack of use. Instead, her joints and spine have taken the pressure and stiffened up in response, and Hallie swears she can feel the creaking whenever she bends down to reach for her boy or turns her head when he calls.

Even her central nervous system—fundamental control center of the body’s functions—is affected by the compression inflicted on Hallie by the way she lives. The system consists of the brain and the spinal cord, which is located inside the spinal column and serves as a transport canal or highway. It is in fact the main highway between the brain, which controls everything in the body, and the periphery of the body—arms, legs, and skin. Dense electric fibers travel up and down the spinal-cord highway to and from the brain. The fibers carry messages of sensory stimuli and motor response, both voluntary and involuntary, back and forth through all the pathways of the body, branching and weaving as needed to get the right response to the right part of the body, then to carry the follow-up message back to the brain, constantly.

When the spine is compressed—especially when the pressure falls on the thickest part of the nerves closer to the spinal cord—the output for motor response becomes less efficient. When the motor output is less efficient, the follow-up sensory input is likewise less efficient. When both the sensory and the motor pathways are less efficient, the entire system becomes less efficient, and that in turn can cause an imbalance in whatever vital process the system handles—digestion and elimination, respiration, immunity, energy, etc. To top it off, most such imbalances occur right at the intersecting points of the weblike, branching formations of neural pathways known as nerve plexuses, bundles of intertwined nerves that branch off the spine and control a substantial portion of the body’s functions. The result is a less-than-optimal working order for Hallie’s entire body, as all interconnected communication systems get thrown off message and further exacerbate the imbalances affecting the organs and the physiological processes that should keep her body in working order. It’s something Hallie can’t see or quite define, but it’s there nevertheless.

Her Nefertiti neck makes the situation even worse.

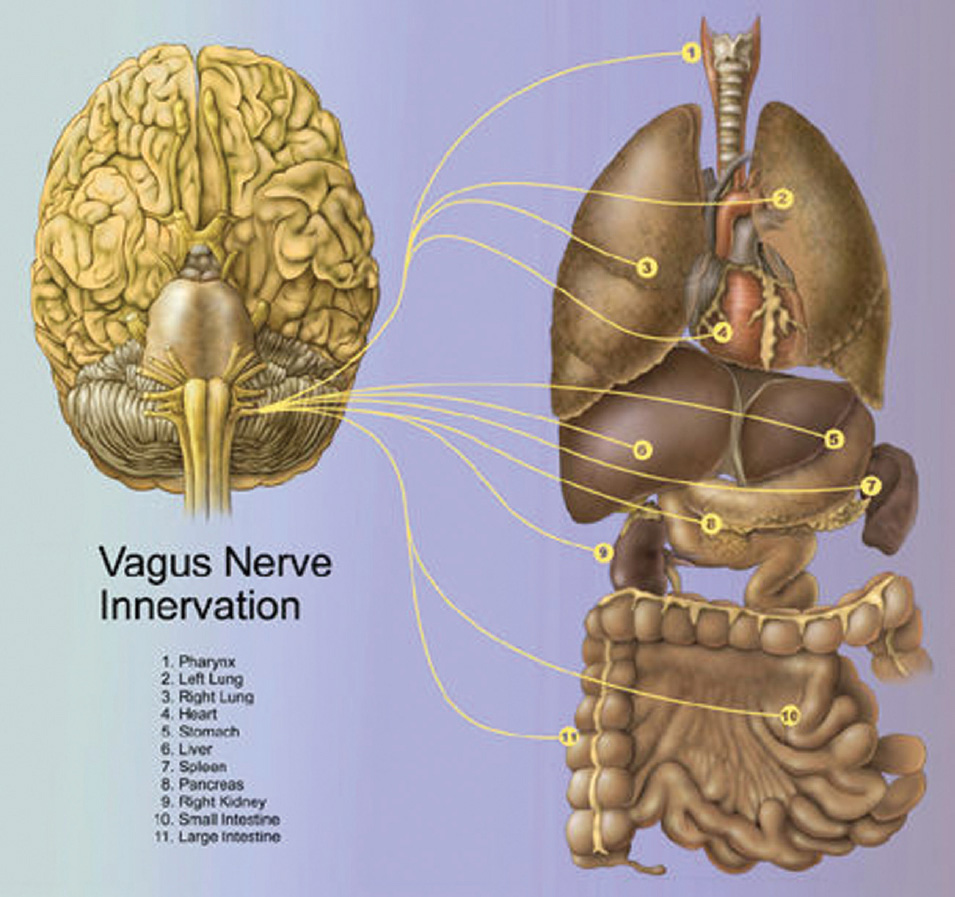

It’s all about the vagus nerve, the longest of the twelve cranial nerves, and one of the longest nerve systems in the body—the name means “wandering.” Among other things, the vagus nerve commands such involuntary body processes as heart rate and the movement of the muscles that keep us breathing as well as regulation of the chemical levels in the digestive system. You don’t want your vagus nerve to get squeezed and affect those functions adversely, but that’s what can happen when the head is thrust forward and the neck muscles are shortened—the anterior head carriage position that virtually defines Hallie’s profile when she is hard at work.

The vagus nerve needs space to communicate the data messages traveling from the organs to the brain.

As to those ills she can define—especially her weakening back and all that tenseness in the neck—Hallie tends to fight them by heading for the gym and putting her body through a fairly demanding fitness workout including Spin cycling, strength training, and weight lifting. She is a passionate performer of crunches—her way of strengthening the bad back—and she is sure the weight lifting keeps her body lean. Maybe. But any engineer will tell you that adding a load onto a structure that is already out of balance is a surefire way to weaken the structure further till it eventually breaks down, and the same is true of the human body. And since Hallie’s posterior chain muscles are already weak through lack of use, strengthening her anterior muscles through crunches just exacerbates that weakness. Hallie keeps making her workout tougher so she can get fitter, and her washboard abs are impressive, but she’s further diminishing her body’s ability to hold a strong posture to push back against gravity. Her intensity aggravates her aching back and neck, and the vague discomfort in many of her joints and limbs. Her workout helps her mind, but it harms her body. This does not have to be.

WE ARE ALL HALLIE

The problem is that in the advanced industrial societies of the twenty-first century, just about all of us are Hallie.

We spend most of our time seated behind the wheel of a car, or in front of a computer screen at work, or poised over our smartphones or tablets as we text and email, or chilling out in front of the television in the evening, or all of the above. This is our norm, the bonus we have gained because we live in societies that spare us the need to do backbreaking physical labor day after day in order to earn our daily bread or put a roof over our heads or gain security for our families.

The upshot is that we have relegated muscles designed to push back against gravity and support our frames to minor roles that ask little of them. Unengaged, those muscles end up collapsing inward onto our joints as compression squashes our bodies, leaving it to the joints to hold us up. That’s a job the joints don’t do very well because they were built for an entirely different purpose—namely, to be the flexible, hinging intersections between bones. What it comes down to is that we’re out of sync with our own bodies, or rather, our bodies are out of sync with what they were designed to do. We are living in a way that is at odds with how our bodies were engineered.

Worse, our bodies have adapted to this discordance—I call it “complacent adaptation”—which modifies into compression. The modifications manifest themselves as chronic lifestyle complaints, persistent weakness, limitations on our activities, and recurring and ever-worsening illnesses—all of which we alleviate, but do not fundamentally fix. Moving wrong—and suffering for it—is the state of our lives and the state of our bodies in the twenty-first century.

COMPRESSION, CHRONIC ILLNESS, AND THE MEDICAL RESPONSE

And how does our health-care system respond to this dire situation? Typically, it does so by suggesting we take a pill, or get a shot, or have invasive surgery. Brilliant when it comes to critical care, medical practice today seems confused in dealing with the debilitating chronic ailments—body aches and pains but also disorders of respiration, digestion, brain function, locomotion, even mood—that now dominate the health landscape.

There’s a reason this is the case. In its genius for specialization, our health-care system has encouraged researchers and practitioners alike to perfect their expertise in separate and distinct areas of concentration. Yes, “miracle” cures have been one result of this, but at the cost of a whole-body systems approach to health care. Chronic illnesses, however, by nature produce symptoms each of which is but a fragmentary message; putting together the fragments to see the whole picture of causation requires just such a whole-body systems approach. And while practitioners today are increasingly—and encouragingly—paying more attention to such an approach, for the most part symptoms are still what gets treated.

Patients and doctors alike tend to look upon every ache as a fresh problem from a cause we haven’t experienced before. Neck pain is seen as both distinct and distant from, say, a digestive order. After all, how could there possibly be a connection? It is quicker and may even appear more compassionate to alleviate a patient’s suffering with one or some of the many treatments available: pills for the headaches and tension in the neck, injections for the backaches and knee pain, and surgery when the bad back becomes so painful and debilitating it limits your life.

The problem is that the relief, if any, is temporary at best, for the pill and the shot and the operation have targeted only a single effect of what is actually a multifaceted cause encompassing numerous connected parts. Even worse, as our bodies adapt to the relief—bodies are almost infinitely adaptable—we need another but stronger pill, another but higher-dose injection, maybe even another surgical procedure. With each iteration of response to the symptom, our bodies are dragged even further away from addressing the original cause; they adjust to the “cure” without our ever confronting the “disease.”

But confronting it means only returning our bodies to their natural postures—something we can do on our own, a fundamental form of self-care. It means relearning how to hold ourselves structurally and how to move muscularly in the way the body was built to be held and to move.

The fact is that our physiology, whether sitting, standing, or on the move, is ideally suited to push back against gravity—and in so doing, to decompress, unfurl, and elongate jammed bodies and experience all the vital power and flexibility of which those bodies are inherently capable. The solution for this modern plague of compression goes right back to the basics of how our bodies work, which is why I call it Foundation Training.