INTRODUCTION

THE JOURNEY INTO OPEN INNOVATION

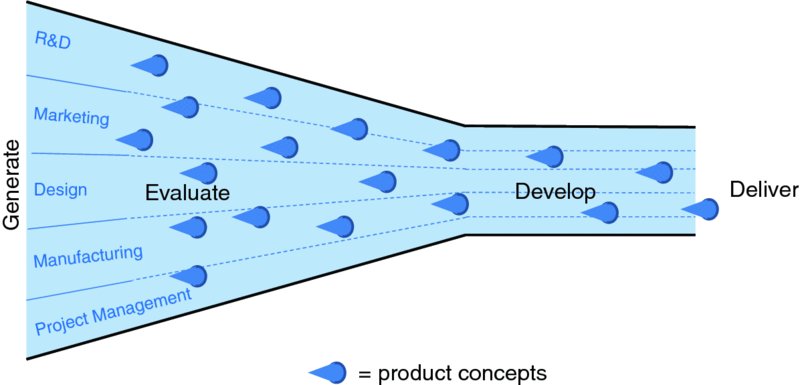

The idea of cultivating firm innovation has long been associated with secrecy, fear of competition, and a general distrust of any entity outside the corporate walls. In this view (shown in Figure 1), product concepts are developed across various organizational functions, but it is a “hard-walled” process in which input from outside the firm is not sought or valued, and concepts are jealously guarded from leaks to the outside world.

Figure 1: A Typical Closed Approach to Innovation

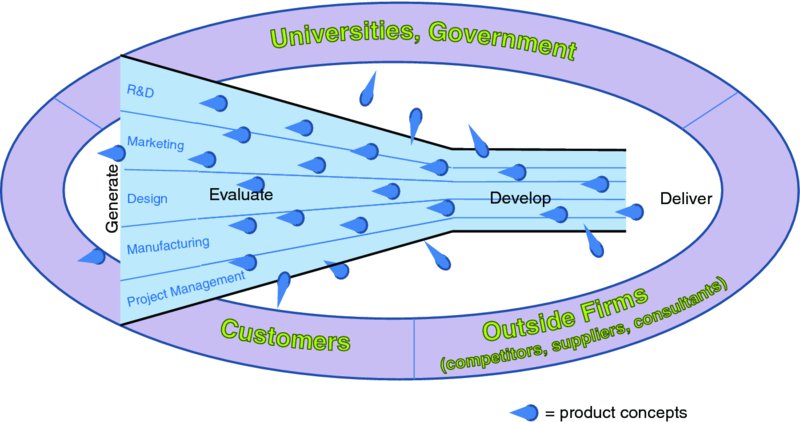

The term “Open Innovation” is generally credited to Henry Chesbrough from his 2005 book and prior writings1, though its origins and concepts certainly appear in earlier thinking. Chesbrough's definition highlights the breaking down of traditional walls and veils of secrecy surrounding the organizational innovation process. As he describes it formally, “[Open Innovation is] . . . the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation and expand the markets for the external use of innovation, respectively.” In somewhat simpler terms, this is “punching holes in the funnel” that historically depicts the innovation process, allowing good ideas, technologies, materials, and other knowledge to flow in, and viable ideas, concepts, and technologies that aren't going to be commercialized by the firm to be passed out through licenses, joint ventures, and other approaches. Figure 2 illustrates this general concept. More than ever, the benefits of Open Innovation (OI) are being explored and under its umbrella can be found increasingly popular techniques such as consumer co-creation, crowdsourcing, idea competitions, collaborative design, and other approaches.

Figure 2: A General View of Open Innovation

Despite the recent focus on this approach, elements of OI have in fact been in existence for centuries. Consider the following:

- In 1714, the British government, through an Act of Parliament, offered the Longitude Prize to anyone who could develop a practical method for the precise determination of a ship's longitude. The winner was John Harrison, who received £14,315 for his work on chronometers.

- In 1795, Napoleon offered a 12,000-franc prize to drive innovation in food preservation, spurring a French brewer and confectioner named Nicholas Appert to develop an effective canning process to avoid spoilage.

- In 1919, New York City hotel owner Raymond Orteig offered a $25,000 reward to the first allied aviator(s) to fly nonstop from New York City to Paris or vice versa. It was a relatively unknown individual, Charles Lindbergh, who won the prize in 1927 in his aircraft, Spirit of St. Louis, and made history.

- In recent years, the X PRIZE Foundation sponsored a space competition and offered a $10,000,000 prize for the first nongovernment organization to launch a reusable manned spacecraft into space twice within two weeks.

- Eli Lilly pioneered the modern idea of crowdsourcing in 2001 when they began to post research questions openly (online) to scientists and other outsiders to augment their own R&D efforts. From this effort, they developed and spun off a new company, InnoCentive, to offer crowdsourcing to other companies.

- The use of “beta invitations” has been practiced for decades in the video game industry. In this model, which could be considered a form of OI crowdsourcing, a software developer releases a “beta” (or early, likely flawed) version to users for testing and commentary. This results in many expert hours of development being applied in a short time, thereby improving the product quickly and cost-effectively.

While these principles have been sporadically tried in the past, the recent move to focus thinking around the term “Open Innovation” has increased attention and has helped explore the full breadth of the concept with its many dimensions and implications.

Despite the hoopla and the calls for many goods and service firms to pursue this approach, there are certainly hurdles and cautions to consider. The loss of control is a fundamental worry, manifesting itself in many ways—in that competitors can have more insight into your early stage product pipeline and in that the same core ideas may be shared with others. There is also a valid concern that allowing users to enter into your innovation process creates an expectation with them that their ideas will be valued and implemented, which may not always be the case, resulting in disappointment. Last is the potentially more daunting worry that “great” ideas can't come from a crowd, which inherently produce compromise and mediocrity.

Idea sifting also can be an overwhelming challenge for firms pursuing this approach with gusto. For example, the community-driven innovation site “Quirky” has, as of this writing, almost 700,000 individuals who have contributed somehow to various product innovation processes—through raw ideas, branding suggestions, design insights, and so on. All of that enormous energy has culminated in only just over 400 products reaching the marketplace to this point. The vast majority of ideas and refinements are rejected, either by the community or, in a more organizationally taxing way, by the firm's own marketing, design, and manufacturing experts. This illustrates the skill shift seemingly required in firms pursuing Open Innovation—from technical expertise in personal product development to screening and sifting through potentially thousands of inputs for a few with “radical” potential. Therefore, it seems fairly clear that cost savings should not be the main driver for the firm embarking down the path to Open Innovation.

Despite these cautions, the general focus on Open Innovation is growing at breakneck speed. A recent report showed that 61 percent of firms were growing or expanding their OI efforts with the focus on partner networks, ideation programs, problem/solver networks, and co-creation programs.2 Interestingly, this study also showed that the drive for OI is largely coming from the CEO level with mid-level and functional management much less likely to be in a championing position. Perhaps you are one of those middle- or even higher-level managers who have been tasked by a well-intentioned CEO to explore this “Open Innovation thing” and this is one of your first steps down that path. If so, you have come to the right place!

This book is not a theoretical treatise on the conceptual underpinnings of Open Innovation, nor is it proposing an untested agenda for further development. In the chapters within, you will find clear and usable tools and ideas to help you implement the principles of Open Innovation in your firm. The authors have taken their lumps and achieved their victories, and share both here. We are fortunate to have insights here from an exceptionally talented group of innovators and appreciate their willingness to share this knowledge. This is a collection of stories of the OI journey, not all of which may apply to your particular situation, but which will inspire you shake up your own approaches to maximizing your innovation potential.

In this book, we consider applications of OI principles in all phases of the new product development process—from idea generation to evaluation, development, and delivery (i.e., launch). The views and techniques offered come from authors with diverse and exciting experiences. This exploration is useful in understanding the full breadth and potential of an incredibly rich concept in Open Innovation. We summarize these insights in several ways, including a model of Open Innovation which highlights the contributing perspectives of this book. We think you will enjoy the offerings here, as a source of thought-provoking ideas for your own OI applications.

Why Open Innovation?

As described in various previous writings in the area, there are many reasons to consider the route of Open Innovation. Briefly, these include the value of bringing in new, outside perspectives on innovation challenges, the ability to profit from ideas that weren't necessarily initiated within the company, increasing speed through development to market, and the ability of smaller firms to effectively scale up innovation resources to match those of larger competitors.3 Many companies seek OI for both “inbound” and “outbound” innovation benefits. From an inbound perspective, OI can complement traditional, internal R&D. On the outbound side, OI principles are used to find creative markets and earning opportunities from developed ideas that aren't put through a traditional development pipeline.

There are numerous examples of Open Innovation successes in the popular press, including efforts such as Heineken's “Ideas Brewery,” an OI portal which asks for creative solutions to specific problems. In one effort to better understand the beer needs of 60+-year-old consumers, winning entries including fruitier and sweeter brews to suit more senior tastes, added iron (an important mineral for the elderly), and easier-opening packaging concepts.4

In a more unusual setting, the U.S. Department of Defense launched a major OI program in 2010 to design the next-generation infantry fighting vehicle through a series of design challenges. Their goals were to achieve a broader range of ideas and to be able to develop a final product at a lower cost. In developing the Fast Adaptable Next-Generation Ground Vehicle (“FANG”) program, three independent challenges were created. The program was launched in 2013 and received widespread participation from those trying to design key components of the vehicle, likely motivated by the $4 million in prize money at stake. To date, the first round of the competition has received over 200 submissions and the military is extremely impressed with their quality and is looking to continue the approach.5

Despite these successes, Open Innovation has also been shown to be, at times, hazardous or at least not particularly worthwhile. For example, Mountain Dew recently launched an Apple-flavored product variation and decided to build consumer support by running a crowdsourcing competition (titled “Dub the Dew”) to let people name the new beverage. Not surprisingly, particularly given their youthful and somewhat irreverent target market, the crowd decided to show their wit with “Top 10” name submissions including “Hitler did nothing wrong,” “Gushing Granny,” and “Diabeetus.” Clearly, the potential for loss of corporate control was striking here. In the end, the company cancelled the contest and used the quite unimaginative “Apple Mountain Dew” as the final product name.6

In another recent effort, McDonald's decided to use the Twitter hashtag #McDStories to encourage customers to share their McD's experiences. Unfortunately, the results were not the collection of shining brand championing they were hoping for, but included public comments such as, “One time I walked into McDonalds and I could smell Type 2 diabetes floating in the air and I threw up,” and “I lost 50lbs in 6 months after I quit working and eating at McDonald's.”7

Clearly, Open Innovation is not a panacea and can present challenges that must be carefully managed. That challenge became the genesis for this book—to offer battle-tested insights on the most effective ways to apply OI ideas across a variety of situations and industries—and to discuss both the key success factors and pitfalls encountered. This is the general format our authors follow in the chapters ahead, helping you to capture the benefits of Open Innovation for your situation.

Perspectives on Open Innovation

Gassmann, Enkel, and Chesbrough (2010) have offered an interesting view on the various perspectives which can be taken to consider OI, many of which are represented in this book.8 These include a structural perspective, considering outsourcing and innovation development alliances, a user perspective which examines how users are integrated into the innovation process, supplier perspectives which consider the role of those partners in OI, process perspectives which consider both inside-out and outside-in processes, institutional perspectives which study innovation norms within an industry, and a cultural perspective examining how firms learn to embrace outside influences on a critical process, among other perspectives. These views are most interesting in how they examine the complexity of Open Innovation, both as a process and as an example of organizational change for many firms. This suggests that implementing Open Innovation is not simply a change in process, but can represent a deeper, cultural change, a more committed level of partnering with suppliers, the seeking out of new types of allies, and a general openness in thinking that may create discomfort for many. While the diversity of industries and OI situations makes a comprehensive step-by-step guide for all cases impossible, this book offers a range of ideas that will greatly facilitate instituting a new regime of Open Innovation in your firm.

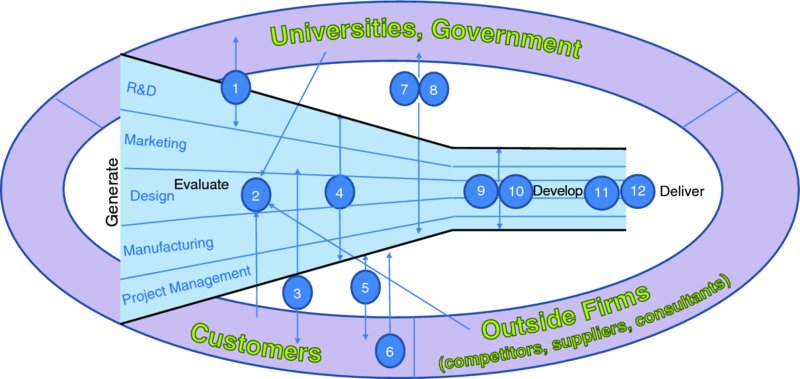

Next, we offer a brief summary of the various chapters in this book. As we lay out, these stories align nicely with the major steps in any innovation and product development process. This mapping of chapters on steps in the Open Innovation process is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The Structure of this Book

Essential Tools for Open Innovation

This book presents 12 chapters to help your firm implement Open Innovation, organized into 5 parts based on where in the product development process the chapter will provide the most utility. Part 1 starts at the left side of Figure 3, offering insights into essential tools for OI in the discovery phase, frequently referred to as the fuzzy front end of product innovation. The flow of subsequent parts moves generally from left to right in Figure 3, with the concluding part providing information on Open Innovation best practices and overall advice.

In Part 1, the book opens with the introduction of tools that you can use for technology mapping and subsequently identifying potential partners for co-development projects. In particular, the authors, Stadlbauer and Drexler, show how emerging technologies can be identified with the use of patent analytics, locate the inventors or firms advancing those technologies, and then, from those that are in close geographic proximity, select the OI partner that best complements your technology capabilities. In their chapter, the authors first make a case for why patents portray the most immediate picture of the technology landscape compared to other sources such as the academic literature. They then summarize traditional patent analytics methods, followed by demonstrations of their method, which is the use of social network analysis in this endeavor. The chapter ends with an illustration of this method as applied to the nanotechnology industry. We think that applying this method in your own firm will be straightforward after reading this chapter.

In Chapter 2, Open Foresight Workshops for Opportunity Identification, Rau and colleagues distinguish between “foresighting” versus “forecasting”: foresight aims to identify several potential futures, while forecasting is done in order to provide estimates of the one most probable future. They then describe four different stages of “open” foresight workshop designs for collaborative opportunity identification. The authors provide the specific benefits gained at each stage when your firm purposefully opens its foresight processes. These benefits include the diversity of insights and perspectives gained, attractiveness of partners, identification of blind spots, trust and relationships built, and sensitization to trends. Rau and colleagues then illustrate how certain companies opened their foresight processes and highlight what steps you can take to open your firm's foresight processes by pointing out specific activities.

Part 2 contains four chapters about various ways to use OI in the development stages—the stages after the fuzzy front end is completed. Our authors show how social media, crowdsourcing, and other types of collaborative processes can improve product innovation efforts.

In Chapter 3, Dubiel and colleagues introduce several important social media applications and cluster them into three levels with respect to their potential uses in your firm's product development process: listening to, dialoging with, and fully integrating customers. These levels range from passive involvement to very active, such as designing proprietary social media content. This chapter's deep content focus is on introducing the netnography process, which is an effective method of using ethnography on the Internet. You will read about several successful implementations of idea/design/solution contests administered by major corporations such as McDonald's and Smart as well as acquire a step-by-step process for executing such a contest for augmenting your own product innovation efforts.

This section continues with a chapter about prediction, preference, and idea crowdsourcing markets, where the author, Koen, first describes the main factors influencing the accuracy of each of these markets. Subsequently, suggesting you keep in mind these factors, he presents different implementation processes for each market type. The chapter concludes with a list of virtual stock market software providers and suggestions on how to choose the right software to effectively open your product innovation process to the crowd.

Next, Kreutz and Benz focus on why and how to employ visual thinking techniques when your employees are partnering with experts outside of your firm or with other firms. Simply put, integrating the tacit knowledge outsiders carry can be daunting because of unfamiliarity with each other's thought worlds and lack of trust. To achieve smooth tacit knowledge transfer, the authors first provide an overview of visual thinking, including the two main types: graphic group processes and knowledge modeling. The authors then explain when to use the two different types of visual thinking techniques and how tacit knowledge is obtained, organized, and presented with these processes.

Part 2 closes with Chapter 6, by Troch and De Ruyck, which provides insights into incorporating customers into your new product development process by using private online communities. In addition to explaining why firms should open up their product innovation processes to potential and current customers via private online communities, they provide a process for doing so. The authors then describe when to use different methods and compare them. Finally, they provide examples and lay out a blueprint for setting up a private user community for your firm.

Part 3 introduces how to implement OI endeavors with universities as partners. First, Spanjol and colleagues share more than a decade of experience at the University of Illinois at Chicago with their interdisciplinary new product development course, in which, so far, over a thousand new product concepts have been generated for partnering firms. The authors present the process followed in a very detailed manner, along with the activities, methods, and deliverables for each step. Chapter 7 will be most helpful for large firms.

The second chapter in Part 3, Chapter 8, provides an overview of similar practices at Massey University, but focuses on smaller firm–university collaborations. In this chapter, Shekar also presents a blueprint for a joint university–company journey and specifies the roles for each stakeholder (i.e., students, supervisors/professors at the university, the industry partner, and the advisory board) in such partnerships. In addition to presenting a project that went through this process, the chapter is full of other useful material such as a sample project agreement and a nondisclosure agreement.

Our book continues with a chapter on depicting OI for really big initiatives. The author, Miller, first talks about innovation impact waves. These are the unintended consequences of innovations, which have created more problems to be solved, even in the face of solving other important problems. The author first identifies the stages and processes for solving “really big” problems and then presents six separate cases where these processes have been applied successfully. This chapter is full of examples of how a wide variety of stakeholders can be brought together and become focused on working swiftly and harmoniously to generate product solutions. Even if your firm is not facing a “really big” problem, the cases may provide hints for enhancing your OI initiatives in general.

The final part of this book concludes with three chapters that portray best practices and overall advice for OI. The first of these, Rainone and colleagues, is a thought piece on the reasons for working with small firms to enhance your innovation muscle. In this chapter, the executives of a small firm present the lessons they have learned during successful OI collaborations. Based on decades of product development support their firm has provided to numerous large enterprises, the authors describe what characteristics you should look for in an OI partner and then best practices when working with small firms, including a timeline for going from initial engagement with an OI partner until the completion of the first set of tasks.

Next, Drexler and colleagues prescribe what senior managers and executives should demand to see periodically so that they stay on top of their game in managing their firm's OI practices. This is especially important considering the emergence of Big Data in the last few years. The authors argue that firms react in two ways to garner the right information from Big Data. The first is to have a data scientist who constantly looks over the huge amount of data firms now gather on a continuous basis. The second is to have a structured way of having these data presented to managers to get a quick snapshot of the current situation. They call this your “daily cup of information,” a sheet that you can carefully look into every morning while sipping your coffee before you start your workday. The authors argue that this cup of collective intelligence, gleaned through the analysis of Big Data, should have an update on specific components related to your business, namely, technology, trends, customers, markets, gap analysis, and competitors.

Finally, Miller and colleagues present the results of the American Productivity and Quality Center's 2013 best practices study for utilizing OI to generate ideas. They define 11 specific best practices associated with the Open Innovation strategies, roles, processes, measurement, and improvement. For each best practice, they provide concrete examples from best-practice firms. The chapter closes with five key enablers that firms trying to improve Open Innovation performance also need to implement.

We hope you will have an enjoyable read and also that this work inspires you to open your own processes to achieve enhanced product innovation results.

Charles H. Noble

Serdar S. Durmusoglu