The Language of Inter-American Relations

Sara Ruiz Valverde

Introduction

The asymmetric relationship between the United States and Latin American countries is a well-known and investigated subject in a variety of political, economic, and sociological disciplines. This chapter uses a sentiment analysis approach, thus bringing the literature and methods of linguistics into the discussion on interregional relations in the Americas. The aim is to make an interdisciplinary contribution to our understanding of interregionalism from an original and often overlooked perspective. A sentiment analysis complements economic and diplomatic analyses in that it captures a more popular mood toward political relations. In particular, the discourse and narratives in the press of three Latin American countries help us understand how interregionalism in the Americas is actually perceived in different areas of the continent. The three Latin American countries selected for this paper are Mexico, at the border with the United States; Colombia, at the crossroad between the Caribbean and the Andean worlds; and Argentina, in the Southern Cone. This selection of countries covers, on the one hand, a large geographical area, and on the other hand a large linguistic variety of lexis, vocabulary, and syntax. Furthermore, each country has its own unique relationship with the United States due to not only its geographic location, but also its specific historical developments and degree of economic interdependence with the United States.

The analysis conducted in this chapter covers the period from January 2016 to July 2017, and deals with four key issues in the Americas: the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA), the Organization of the American States (OAS), the question of migration, and the election of President Trump. The chronological span includes the last year of the US 2016 presidential election campaign, the election of November 8, 2016, itself, President Donald Trump’s inauguration, and his first 100 days in office. The purpose is to detect and assess possible significant changes in language, discourse, and sentiment on the four topics in the press of the three Latin American countries over the target period. The study examines almost 1,600 headlines of major newspapers in Mexico, Colombia, and Argentina dealing with Trump’s statements on interregional relations in the Americas. While his election was an important topic in itself, his comments on NAFTA, the OAS, and immigration led to great uncertainty and anxiety about the US future policy toward the region, not only in Mexico but also in the rest of Latin America. Statements like “Mexico will pay for the wall, 100%” (BBC 2016) and the particular way of expressing them made Donald Trump, his candidacy, and his presidency a hotly discussed topic in the press, with significant repercussions on the way in which the rest of the Americas perceived inter-American relations.

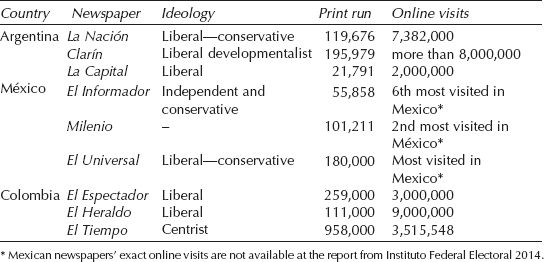

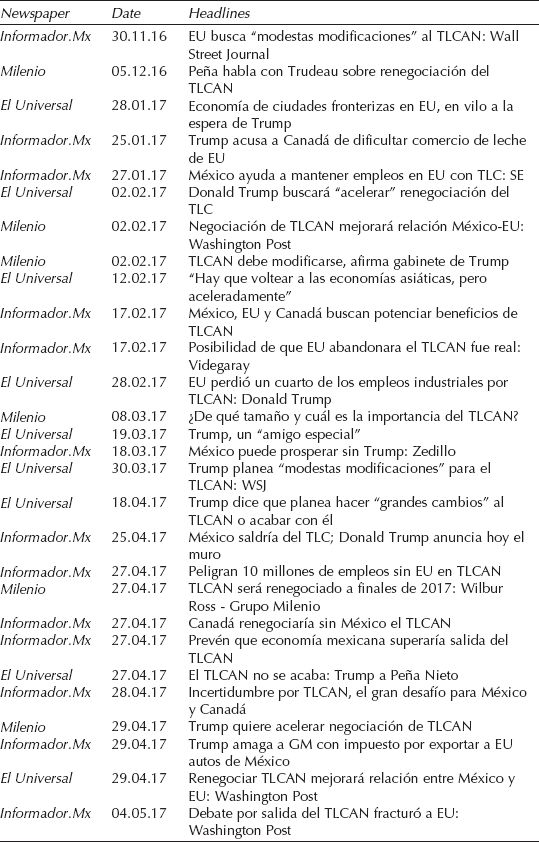

This study analyses the online version of major Latin American daily papers. Given the number of readers of digital press, and keeping in mind that this number is constantly increasing, the analysis of the headlines published online becomes even more important. The selected newspapers (see Table 11.1) represent some of the most widely read journals available online in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico and cover a number of political orientations.1 In Argentina, Clarín is the third most visited paper online in the Spanish language worldwide and is quite sympathetic with “Macrism” and liberal ideas; La Nación is the fourth most visited online paper in the Spanish-speaking world, is also moderately supportive of Macrism but has a slightly more conservative cut. In Mexico, Milenio, from Monterrey, has no explicit political orientation. El Informador, from the state of Jalisco but read in the whole country, and El Universal, from Ciudad de Mexico, both are considered quite liberal and relatively independent from the government. El Universal is the most read in Mexico. In Colombia, El Heraldo from Barranquilla is the third most printed in Colombia but the first online. Both El Heraldo and El Espectador from Bogotá are considered quite liberal in ideas, independent in position, and Catholic in underpinning values. El Tiempo is today the only newspaper published throughout Colombia and is perceived as broadly moderate in tone.

The study uses headlines from these dailies as a source of information about the sentiment toward the United States. The aim is to investigate whether there was a change in journalistic discourse during the campaign and/or after the election, and whether this could indicate a change in the perceptions and the sentiment about interregional relations in the Americas during this period. The validity of this method and of obtaining data from analysis of the media is certified in fields and disciplines other than linguistics too, such as economics, in order to assess and even predict, for instance, changes in stock markets (Tetlock, 2007).

The chapter unfolds as follows: Some methodological and general considerations on sentiment analysis open the discussion. Then, an in-depth analysis of the four key topics follows. Finally, a concluding section will link sentiment analysis with the broader political discussion on interregionalism.

Table 11.1 Newspapers Information

General Considerations and Study Framework

A few notes of caution, especially about methods, are necessary at this stage. On the one hand, media’s adherence to an official agenda and the editorial line underpinning the choice of headlines and their prominence is likely to influence public opinion (Herman and Chomsky, 2008). On the other, the readers’ interests and positions may diverge—sometimes sharply—from that of elites (government, editors, or journalists), and for this reason propaganda is not always effective but could be even counterproductive. These factors must be kept in mind to interpret correctly some of the published headlines.

Media outlets do not exist in a vacuum but are immersed in the sociopolitical reality of their country. Often, the respective governments exercise some degree of influence over the media. This differs in the three sample countries (World Press Freedom Index, 2017). According to this Index, in Argentina, the relationship between the media and the government is more transparent and less polarized under Macri than it was under Cristina Kirchner. In Colombia, the WPFI considers that the situation has also improved since the peace agreement with the FARC was signed. In the case of Mexico two large media groups own almost all the press media and major TV channels in the country (Reporters without borders, 2017).

In methodological terms, this study combines two methods to extract information from the headlines corpus about the sentiment of the three Latin American countries in relation to the United States and interregionalism:

• Typical tools of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA).

• Typical tools of Sentiment Analysis (SA).

According to Stecher (2009), CDA has a disciplinary identity which is characterized by a mixture of a strong foundation in linguistic tradition on the one hand, and a transdisciplinary vocation on the other. Furthermore, Van Dijk (2003a) positively emphasizes that CDA should be essentially diverse and multidisciplinary. In this case, it would be logical to use discourse analysis as a single tool. However, this was not possible due to the minimal length of texts without context (Wang et al., 2013), which characterizes press headlines, and the immense volume of headlines. A different and complementary tool was needed: sentiment analysis. The ease of access to the online press using all the available digital platforms, such as smartphones, tablets, laptops, has changed the readers’ attitudes into one that can be described as “Not interested anymore in the news unless the headline is really shocking. What the average reader nowadays basically does is read the first 140 characters as a tweet” (Excelsior, 2017).

This explains why more and more headlines are written in the form of a tweet. Therefore, the same classification tools and techniques as used in SA to extract specific information from headlines must be used. SA gains more and more importance for the realization of market and social studies and polls by taking advantage of the exponential increase of users of social networks. Since news headlines have limited length and we are not analyzing the full details of the news, SA is a priori a good method.

On the one hand, SA conducts computerized studies to obtain quick results on the feeling toward a subject or public personality in a country. SA classifies terms which were chosen in advance to create a sentiment lexicon or “bag of words” in three categories according to the feelings they represent: positive, negative, and neutral terms. However, sentiments are subjective impressions, not facts. A binary opposition in opinions is assumed (Mullen, 2004) and we should be aware that the analysis is based on sentiments and not always measurable facts. On the other hand, SA can lead to errors since a computer program does not have the ability to detect the difference between “positive or an irony” (Piñeiro, 2011; González Dulanto, 2016). It also lacks the perspective of linguistics and discourse analysis (Pardo, 2007). As an example, a headline published in Colombia: Negociando con el lobo (Tiempo, 2017b): here wolf refers to Donald Trump. In Spanish literature, the wolf always plays the role of a dangerous character. The headline expresses the situation of negotiating with Donald Trump perfectly: wolf = danger = Trump. The result of a SA would be neutral, but a CDA would say it is negative.

For this reason, an analysis from syntax, and the verbal and paraverbal organization of the communicative event is necessary to avoid an error in the analysis performed by a machine (van Dijk, 2003b). In some cases, it is important to consider the paratext in order to understand a headline; the irony or the accompanying photograph can give us the sentiment. An example could be: The day before the US elections, for example, the following expressions and words were used in the headlines: cierres maratónicos, cortejo a los indecisos, el mundo en vilo. These illustrate the feeling of uncertainty in each of the three countries but without any indication of being in favor of one of the candidates. The accompanying pictures, however, gave a hint about the editorial line.

Furthermore, a multidisciplinary work is necessary to interpret the results achieved by doing SA in terms of political issues or related to international relations. An expert in linguistics may not be able to interpret some of the findings alone. As an example, a headline published in Colombia referring to “the wall” is very enlightening from a sentiment analysis point of view. It offers a positive result but it could not be consistent with a political analysis: Trump habla de muro, China levanta puentes con Latinoamérica (El Heraldo, 2016). The words “wall” and “bridges” share a headline. “Wall” takes on a negative connotation in Trump’s political discourse. From the language perspective “to build bridges” has a clearly positive meaning as it involves cooperation, initiative, and strengthening relationships. However, from a political and economic point of view, could it be invariably classified as positive if China builds a bridge to Latin America? What would be the long-term impact and consequences? The political picture may not be fully captured and requires additional elaboration.

In order to achieve valid conclusions on the sentiment in a country regarding a certain political topic or politician, it was necessary to set up an adequate corpus of newspaper headlines. Initially a search was conducted to find all headlines on the topic of OAS, NAFTA, and immigration (for the US elections a different approach was used as explained at the beginning of the section 3.3) by making a press clipping at the digital periodical libraries of the nine newspapers. This search provided almost 1,600 headlines. The corpus was classified by using two different criteria.

The first criterion focused exclusively on the headlines published on front page. The aim was to find the same news in all three countries and compare the difference in the use of the language, trying to extract whether the sentiment in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico differs and why. This exercise is particularly illustrative in the case of headlines regarding US presidential elections as it will be discussed in the last case study. But news related to NAFTA and the OAS is usually not front-page material in any of the three countries. For this reason, the selection of headlines chosen to draw a sentiment development line has been made by a non-probabilistic sampling of key dates. For each date we found three headlines in each country, which means nine headlines per date which gives us a general idea how the sentiment was at the time in each country.

The second criterion for analyzing the corpus was to select all headlines published on the topic of NAFTA and OAS, migration, and elections. The aim was to quantify them in order to determine the importance that a country gives to a topic given the number of headlines published during the analyzed period. Keeping in mind, on the one hand, that policy makers try to influence readers (agenda setting) and, on the other hand, that readers may demand more information on a topic for different reasons, one may wonder if the number of headlines is in fact consistent with the importance that a topic has in the target country. Once again some caution is needed here when analyzing the data.

Case Studies

Regional Organizations: OAS and NAFTA

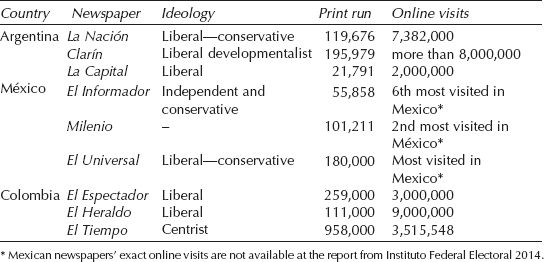

This section analyses headlines on the OAS and NAFTA. These headlines exemplify sentiments and attitudes in the three countries over the target period on the issue of regional/interregional organizations. Argentina, Colombia, Mexico, and the United States are all members of OAS, and only Mexico and the United States are NAFTA members. In relation to this, the existence of a difference in the number of headlines appearing in these countries is logical. NAFTA has generated a plethora of headlines due to the continual declarations of Trump during his campaign, and afterward due to his stated intention to withdraw from the treaty. But surprisingly, the number of NAFTA headlines found between January 2016 and May 2017 is significantly lower than the number of headlines referring to OAS. Unexpectedly, Mexican headlines on OAS are much higher than on NAFTA—almost 680 headlines regarding OAS and only 238 about NAFTA. This is especially surprising as NAFTA is vital for the Mexican economy and as the United States and Mexico share land borders, while Argentina and Colombia are not NAFTA members and are distant neighbors to the United States. This divergent importance of the topics in each country is a significant finding in itself. The following graph shows the percentage shares between the topics on NAFTA and OAS in the published headlines in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico.

In Argentina the number of headlines referring to NAFTA is about 16% compared to the 84% of headlines about the OAS. Given that Argentina is not a NAFTA member, this seems appropriate. In the case of Colombia, the proportion of headlines referring to NAFTA is considerably higher than in Argentina and Mexico. Argentina however seems to show greater interest in the evolution of the treaty according to absolute numbers with around 30 headlines in total. The interest might be explained by the following headline: Por su pelea con Trump, México analiza comprar soja a la Argentina (Clarín, 2017), which suggests that possible alterations to NAFTA may lead Mexico to trade more with Argentina. The tone of the headlines referring to NAFTA in Argentina is mostly quite neutral.

Figure 11.1 Percentage between the Topics NAFTA and OAS in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico. Source: Author’s figure.

In Colombia, six headlines referring to NAFTA are neutral and eight are negative, one headline with a positive sentiment toward Trump was found. On January 24 the headline in El Espectador reads Para Colombia, Trump es una oportunidad (El Espectador, 2017), headline cited by the minister of economy, María Claudia Lacouture. This indicates that Colombia may have perceived itself as an alternative to Mexico for the United States at that moment.

In Mexico, important differences in the number of headlines published on the topic of regional organizations (OAS and NAFTA) by different daily papers have to be highlighted. In Milenio, we found only six while most headlines were from El Universal (212 in total). The fact that most of the news in Mexico comes from El Universal is important: One reason could be that they publish new headlines for their cell phone application every hour. The other reason could be a political one, by trying to support the government publishing a large amount of news about OAS where President Peña Nieto could take a more proactive role as a policy maker as opposed to NAFTA where he was not in a position to decide what was going to happen.

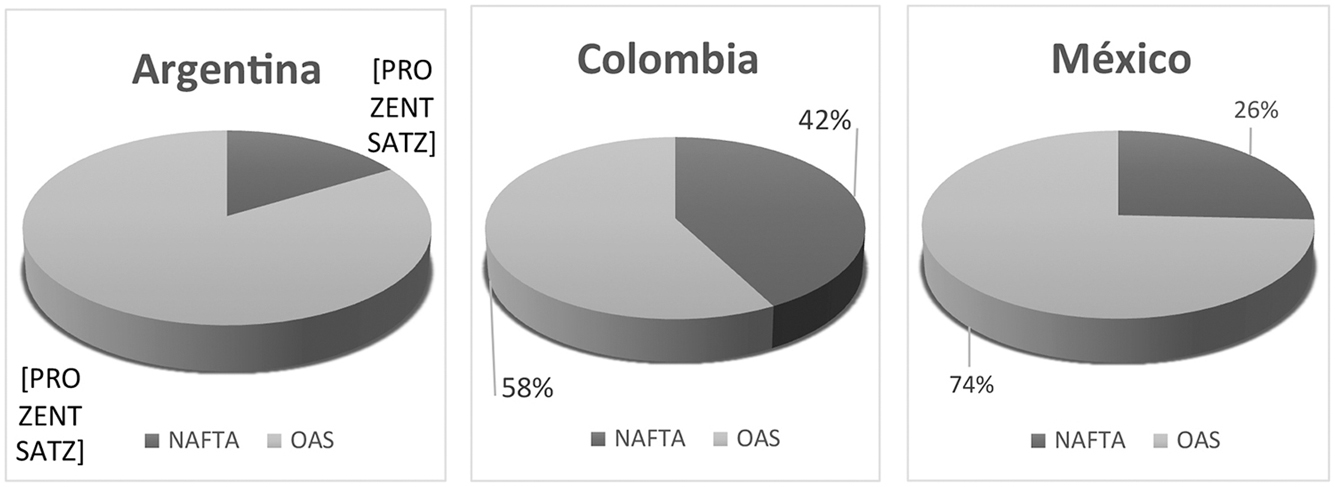

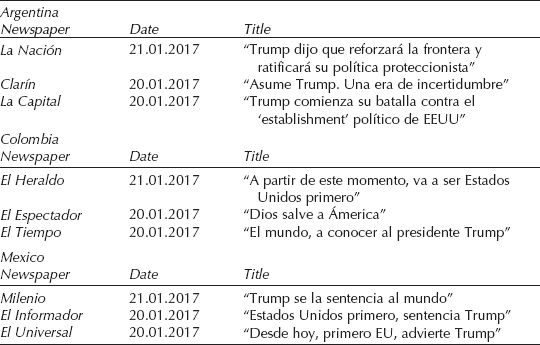

To gain a sense of what Mexicans feel when Trump talks about NAFTA, and knowing that this sentiment can influence the country’s economy, all headlines published in the three Mexican newspapers (El Informador, Milenio, and El Universal) must be considered. Below, we present all the headlines published in Mexican newspapers between November 2016 and May 2017.

Terms marked in grey are the ones with great importance for the SA. From November 2016 on the three papers analyzed in Mexico wrote about the intentions of Donald Trump to renegotiate or withdraw from NAFTA by July 2017. But renegotiations are going slower than expected—and announced—and withdrawal did not happen. Analyzing the changes in the discourse one could argue that the results do not suggest a negative sentiment on the part of Mexico toward the United States about NAFTA but a confused sentiment: Donald Trump announced major changes in policy regarding NAFTA several times during his last year of campaign. On April 18, 2017, Trump, already president, declared the US withdrawal from NAFTA only to state shortly afterward on April 27, 2017, that this would not happen.

In Informador and Milenio, divergent tones and styles are used to communicate the same information. There are headlines with a much more sensationalist touch in Informador with expressions such as “uncertainty,” “millions of jobs are at risk,” or the use of the conditional Mexico could survive without NAFTA. Milenio uses much more moderate headlines. El Universal, on the contrary, wrote on the same day NAFTA is not over: Trump to Peña Nieto. This is the newspaper with the highest circulation in Mexico. It opts for a much more reassuring headline while showing that NAFTA’s continued existence was not the merit of the Mexican president, and that Peña Nieto is not the one in a position of power nor the decision maker, Trump is (El Universal, 2017b). Nonetheless, the consequence of Trump changing his mind fuels uncertainty about NAFTA, in all three countries analyzed. In summary, regarding NAFTA, Argentina and Colombia had a neutral-negative posture and Mexico had a confusing sentiment toward the United States during the analyzed period.

Table 11.2 Headlines about OAS

Table 11.3 Headlines about NAFTA

Table 11.4 Headlines about NAFTA from 01.11.2016-30.05.2017 in Mexico

Most of the headlines about the OAS are neutral because they mostly relate to Venezuela directly and not the United States. US absence is perhaps the concept that best sums up the sentiment in all three countries regarding the United States or Trump positions on the OAS. If one negative sentiment emerges, it is that in Argentina and Mexico, the headlines imply a “sentiment of anger” toward Trump because he is not taking part in deciding about Venezuela. No positive terms appear in the headlines regarding OAS during the analyzed period. In Colombia, most probably because of territorial proximity to Venezuela and political proximity to the United States, a neutral, moderate attitude prevailed throughout the period examined.

Immigration

Controversy and insecurity about immigration and the new policies to be undertaken by President-elect Donald Trump generated an immense number of headlines for two kinds of consumers: on the one hand, readers who could be directly affected by such measures, the type who fears headlines such as Peligran 10 millones de empleos (Informador.Mx, 2016). On the other hand, the large number of readers more interested in controversial, sensationalist, or morbid topics.

A problem appears when the informative function of the serious press begins to reach the level of the yellow press. The topic of the wall provokes headlines in Argentina and Colombia such as Donald Trump quiere fijar un impuesto de 20% a las importaciones mexicanas para pagar el muro (La Nación, 2017b) or Trump busca fijar impuesto de 20% a importaciones mexicanas para pagar el muro (Tiempo, 2017a). Or in Mexico, headlines such as México saldría del TLC: Donald Trump anuncia hoy el muro (Informador.Mx, 2017a) or México puede prosperar sin Trump (Informador.Mx, 2017b). These headlines express anxiety for the general public and may generate uncertainty and lack of confidence for foreign investors. Indeed, at the time these fears and controversies had already had a serious impact on the markets.

In terms of a SA, Donald Trump’s controversial statement No quiero nada con México más que construir un muro impenetrable y que dejen de estafar a EE.UU (BBC Mundo, March 6, 2015, vía Twitter.) during the campaign led almost to a panic-like state. Political speculations about Donald Trump’s presidency and the negative sentiment so generated are probably two of the reasons why the world stock markets fell. In foreign policy, “reinforcing the border” of a country, as mentioned in La Nación (Argentina), Trump dijo que reforzará la frontera y ratificó su política proteccionista (La Nación, 2017a) might be a positive measure by a government. In terms of terminology per se, the verb “reinforce” has a positive connotation but what kind of sentiment does a statement like this create in the Mexican neighbors?

The discourse of the wall goes so far that on January 28, 2017, Presidents Donald Trump and Enrique Peña Nieto agreed not to continue to talk about the subject in public anymore: Donald Trump y Enrique Peña Nieto sellan un “pacto de silencio” por el muro (La Nación, 2017c). After this pact of silence, the headlines change the tone of the discourse and become more moderate, as we see in the following examples: “resetting the relationship” México y EU viven un “momento de definición” de relaciones (Informador.Mx, 2017c). “NAFTA means a positive relationship” TLCAN mejorará relación México-EU. Afterward the stock market has a rise consistent to this more positive sentiment in the press. In May 2017, President Trump rectifies: Trump rectifica: EU pagará por el muro y México lo reembolsará (Informador.Mx, 2017d).

To what extent has the profitability of the newspapers been influenced by publishing controversial statements by Donald Trump which blow the renegotiation of NAFTA or the wall out of proportion? It is a fact that at least in Argentina, subscriptions to newspapers have been increasing since Trump’s presidential campaign and election more than ever before. It is also a fact, according to Retegui (2017), that politicians use media as their voice, and that media without politicians “have no news.” Argentina expects the best relationship with United States ever (Trump to Macri: Espero que Argentina y EEUU tengan la mejor relación de su historia) (Infobae, 2017) but the sentiment given by the headlines of papers with different ideologies are “not playing the game.” Due to how Trump expresses his opinion about immigration and the wall—and also about his intentions to leave NAFTA—(Informador.Mx, 2017a), none of the three countries have published headlines with a positive sentiment toward him in the period studied in this chapter. Only negative or neutral headlines were found.

The US Presidential Elections

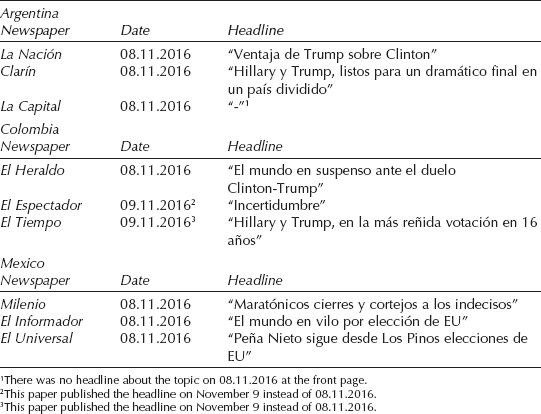

Here, the headlines used for the sampling were on the front page of all newspapers. Three critical dates were chosen: November 8, 2016, when the election took place, November 9, the day after the election when the results came in, and January 21, the day President Donald Trump was inaugurated.

The day before the US elections, the following expressions and words were used in the headlines: cierres maratónicos, cortejo a los indecisos, el mundo en vilo (Marathon closures, courtship of the undecided, the world hanging on a thread). These illustrate the feeling of uncertainty in each country. In the headline there is no indication of being in favor of one of the candidates, although sometimes the accompanying pictures gave a hint of the newspapers’ preferences.

In Argentina, from a SA perspective, the headlines are neutral. “Trump’s advantage over Clinton” does not have any negative connotations. However, Clarín uses Donald Trump’s last name and Hillary Clinton’s first name. This may imply a distancing of the paper from one of the contenders and/or express empathy to the other. Alternatively, this might be just about the jargon in use both in the press and the public. In Colombia, “the world in suspense” or “uncertainty” does not indicate direct support for either candidate. In El Tiempo headline, Hillary is also mentioned by her first name like in Argentina. In Mexico, headlines read “courtship of the indecisive,” “the world in suspense.” These headlines are neutral. However, the sentiment of “uncertainty” was real in all three countries because of the statements made by Trump in the lead-up to the election. Overall, one can safely conclude that the sentiment in the headlines in all three countries on Election Day was neutral.

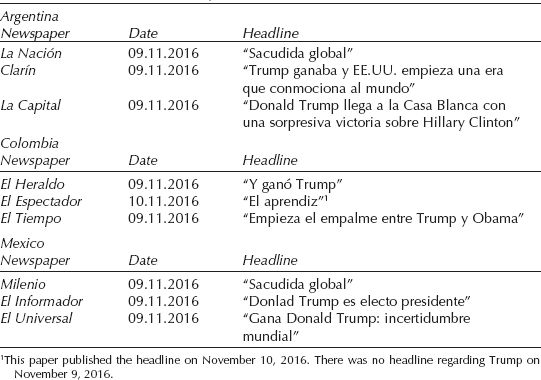

These headlines mark a change in tone. No positive headlines were published in any of the three countries. They are clearly negative or neutral as headlines such as “shocks the world” or “an era of uncertainty” clearly indicate. In the main papers in Argentina (La Nación and Clarín) and Mexico (Milenio and El Universal) all headlines are negative. Colombia is the country with the most neutral headlines where two out of three headlines belong to this category. This may depend on the close relationship that Colombia maintains with the United States and the need to keep it with whoever the winner was. In this sense Donald Trump might have not been considered a decisive factor to US-Colombian relations, which are more of a state policy than a government policy. No positive terms however can be found in any of the newspapers in the three countries: “result shocks the world,” “shock,” “jolting the world,” “global uncertainty,” “surprise victory,” “the apprentice.”So the prevailing sentiment is negative in Mexico and Argentina and neutral in Colombia.

Table 11.5 November 8, 2016: The Election Day in the United States

Table 11.6 November 9: The Day After the Election

Trump says he will strengthen the border and implement his protectionist policy (La Nación, Argentina, January 21, 2017a) and promotes his slogan “America first.” Such statements are not welcome in Argentina and Mexico as they might have a negative effect on these countries’ economic relations with the United States. In Mexico we read headlines such as: Trump sentences the world (Milenio) and America first, sentences Trump which sound clearly alarming and are sensationalist formulations. A president like Donald Trump who during the election campaign and afterward as president made such a large number of provocative statements about his plans to leave the NAFTA treaty, deport Mexicans, and fight against the US political establishment quickly becomes the focus of attention in the press. It is likely that editors even welcome statements of this kind as they are likely to increase their sales. However it is much more likely that these tones actually reflect a position of concern throughout Latin America. In fact, even in Colombia, which had been quite neutral that far, we read headlines like God Save America! in El Espectador. This is a clear departure from the moderate Colombian posture until then.

Table 11.7 January 21: Inauguration Day of President Donald Trump

This analysis confirms the pattern that we have already seen previously: the sentiment on January 21 in Argentina and Mexico was negative and almost neutral in Colombia. Once again, no positive sentiment develops at the time in any of the three countries.

Conclusions

Headlines in the press are of key importance, among other reasons because they evoke a sentiment. This sentiment expresses editorial and political preferences on the one hand, and influences the readership on the other. The formulations used are finely honed to hook the readers’ attention and convey specific messages and attitudes. Using key expressions and adjectives or semantics, headlines transmit a certain sentiment that captures, and is somehow representative of, the public mood or segments of it. An analysis of the headlines written from a Latin American perspective gives us an idea of the sentiment toward a topic, in this case, toward the United States, President Donald Trump, and inter-American relations.

The results of this study confirm that there was a change of sentiment—and at the discourse level—toward Donald Trump and interregional relations during the time span between January 2016 and July 2017. During this period, Argentina and Colombia have changed their tone. The sentiment became more negative around Election Day and in the aftermath to the election than it had been since the beginning of 2016. The sentiment turned slightly more moderate in Argentina and Colombia when the two countries realized that problems between the United States and Mexico might bring some advantages to their economic and political strategies. In Mexico, sentiments of confusion and anxiety preceding the presidential election turn into quite openly negative after the election, when Trump’s campaign statements began to be turned into policy.

Just one single headline with a positive sentiment toward Donald Trump in Colombia (El Espectador 2017) could be found. Overall, the sentiment toward the United States and interregional relations was quite negative at the beginning of 2016, and it remained significantly negative in Mexico and quite negative or at best “almost neutral” in Argentina and in Colombia.

The sentiment that one single headline can evoke on readers can have more effect on the public opinion than a large quantity of more moderate ones. In the analyzed corpus, the number of published headlines referring to NAFTA, OAS and immigration is quite different in Argentina, Colombia, and Mexico. This absolute number of headlines was not necessarily consistent with the impact or sentiment they provoke. Indeed, the difference in the number of headlines published about a topic in each country is a significant finding in itself as it shows that the highest number does not necessarily mean that the topic is the most important for the country’s politics or economy. NAFTA and the wall had much fewer headlines than OAS across the board. Nevertheless, readers were talking about the wall and NAFTA on social networks much more than they did about OAS.

The conclusion is that the content of the press headlines is not always meant to please the target audience. It is true that SA alone cannot determine the extent of the influence that headlines (used as a propagandistic tool) have on public opinion. However, it is also true that SA can detect a certain sentiment, mood, or attitude working on getting the readers in the desired direction. This study argues that two factors certify the existence of the propagandistic bias: on the one hand, the quantity of headlines published related to certain topic, and, on the other hand, the connotation behind every headline and its intentionality.

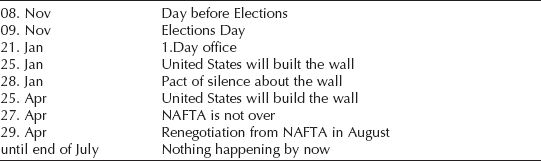

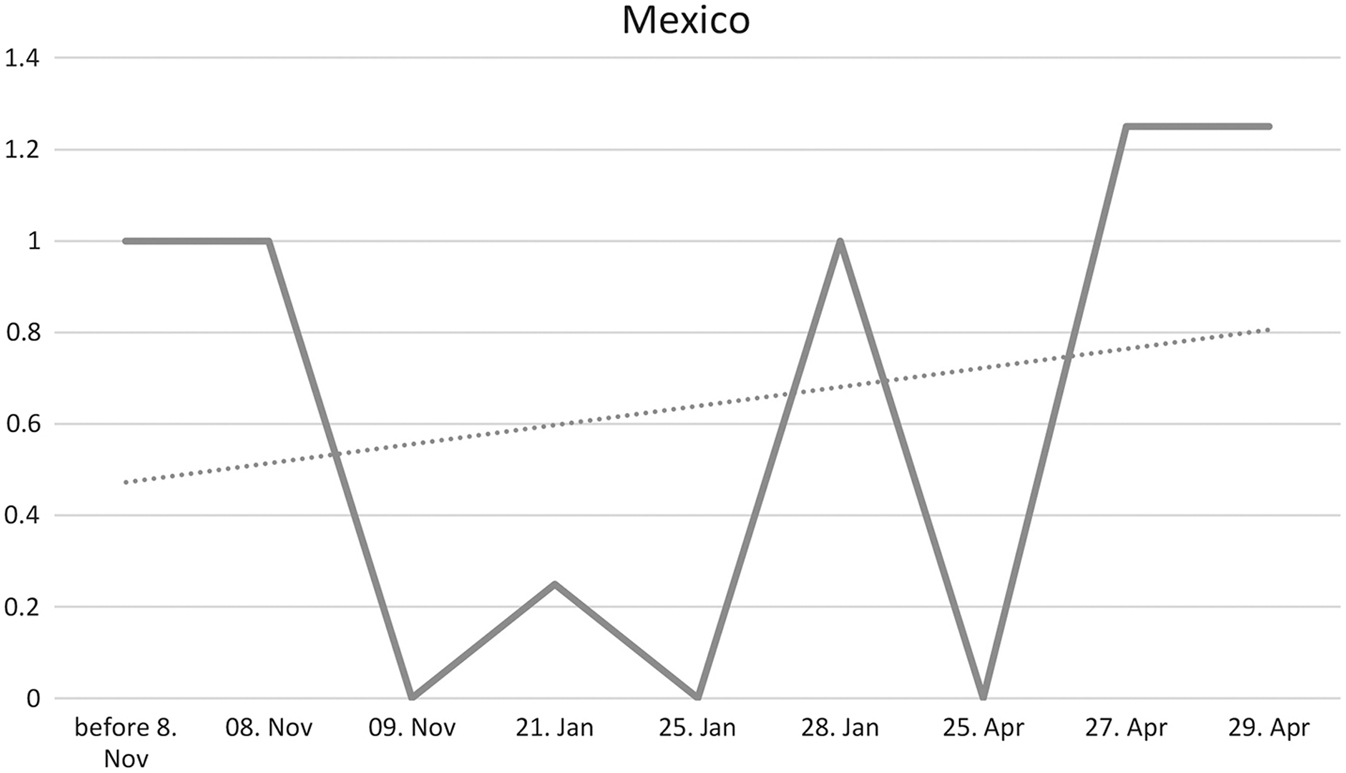

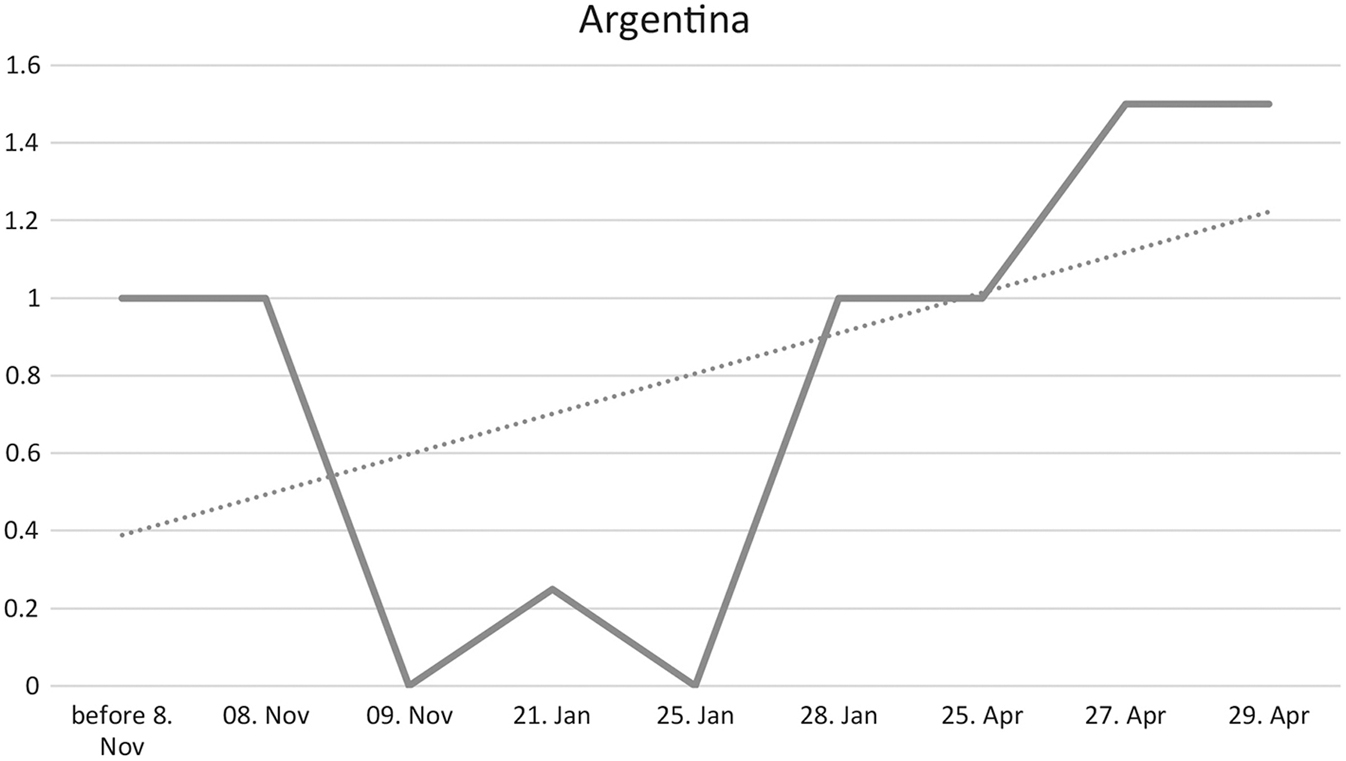

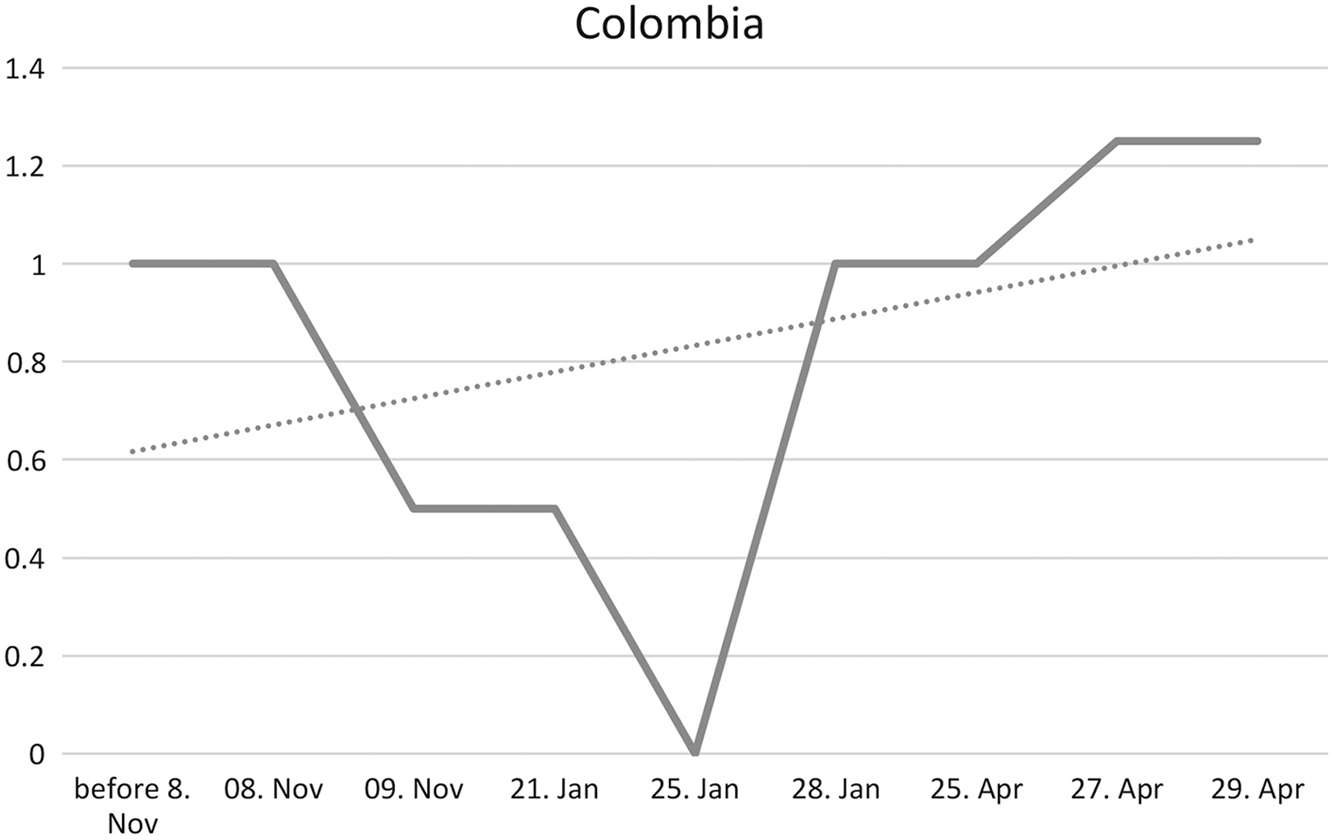

The classification of the terms contained in a headline in the categories neutral, positive, or negative helps us to extract the sentiment of this propaganda. These sentiments are measurable. Thanks to the categorization, it is possible to draw a Sentiment line to see the development or change in the discourse in a period. In the following tables, the reader can visualize the change in the sentiment development line in the three countries vis-à-vis the United States across the target period. The Table 11.8 shows the key dates to assess and give political meaning to the sentiment line.

Before Election Day, the sentiment line in the three countries is not positive but is relatively stable. From Election Day to the inauguration of President Trump, the situation worsens considerably in all the three countries, although with different peaks and patterns. This is due to the state of uncertainty about the US future policies and the resentment that the electoral campaign had provoked, also in Latin America, and especially in Mexico. The sentiment becomes less negative after the conciliatory tones of President Trump’s inaugural speech. At this point, the sentiment in Argentina and Colombia remains stable or tends to improve as none of the harshest measures announced by Trump seem to materialize or to have a major impact on the two countries. The picture is significantly different in Mexico, where the sentiment line falls in coincidence with the wall announcement on April 25, 2017, but then recovers when the US unilateral withdrawal from NAFTA does not take place and the negotiations on NAFTA do not take the terrible contours expected on the Mexican side.

This chapter contributes an interdisciplinary perspective to the book. It also broadly discusses interregional relations in the Americas with a focus on four key topics: the OAS, NAFTA, migration, and the US elections. Obviously this chapter cannot add to the discussion on the categories and typologies of interregionalism. Nonetheless the approach followed here very much resembles hybrid interregionalism to the extent that Colombia, Argentina, and Mexico represent a Latin American voice vis-à-vis one country, the United States. No contribution can be made to the discussion on summitry. But this interdisciplinary input from a linguistic perspective confirms one peculiarity about interregionalism and the Americas: the trend toward a distinct Latin American side from a North American side, embodied by the United States. Also the language and sentiments analyzed in this chapter confirm that there is not one America but many Americas and their perceptions and modes of interregional relations are sharply different.

Table 11.8 Key Dates to Give the Sentiment Line a Political Meaning

Figure 11.2 Sentiment line from Mexico. Source: Author’s figure.

Figure 11.3 Sentiment line from Argentina. Source: Author's figure.

Figure 11.4 Sentiment line from Colombia. Source: Author’s figure.

Note

1. Table 11.1 was compiled by the author consulting several sources of information: for Argentina: Instituto Verificador de Circulaciones (Moreyra 2017), for Mexican newspapers: Instituto Federal Electoral (2014), and for Colombian newspapers: Estudio General de Medios (2016).

References

Abril, N. G. P. (2007). Cómo hacer análisis crítico del discurso. Una perspectiva latinoamericana. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

BBC. (2016). Donald Trump: Mexico will Pay for Wall, 100%. Retrieved June 24, 2017, from http://www.bbc.com/news/election-us-2016-37241284

Clarín. (2017). Por su pelea con Trump, México analiza comprar soja a la Argentina. Retrieved June 25, 2017, from https://www.clarin.com/ieco/pelea-trump-mexico-analiza-comprar-soja-argentina_0_BkzZomQtl.html

Clarín. (2017). Desplante de EE.UU. a la Comisión de Derechos humanos de la OEA. Retrieved June 3, 2017, from https://www.clarin.com/mundo/desplante-ee-uu-comision-derechos-humanos-oea_0_HyYhhfynx.html

Cook, F., and Tyler, T. (1983). Media and Agenda Setting: Effects on the Public, Interest Group Leaders, Policy Makers, and Policy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47, 16–35. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.840.7379&rep=rep1&type=pdf

El Espectador. (2017). Para Colombia, Trump es una oportunidad. Retrieved July 1, 2017, from http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/economia/colombia-trump-una-oportunidad-articulo-676421

El Heraldo. (2016). Trump habla de muro, China levanta puentes con Latinoamérica. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.elheraldo.hn/mundo/1018988-466/trump-habla-de-muro-china-levanta-puentes-con-latinoam%C3%A9rica

El Universal. (2017a). EU deja plantada a la CIDH en audiencia sobre plan migratorio de Trump. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/mundo/2017/03/21/eu-deja-plantada-la-cidh-en-audiencia-sobre-plan-migratorio-de-trump

El Universal. (2017b). El TLCAN no se acaba: Trump a Peña Nieto. Retrieved June 15, 2017, from http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/articulo/cartera/economia/2017/04/27/el-tlcan-no-se-acaba-trump-pena-nieto

Estudio General de Medios. (2016). Boletín 2—Ranking Prensa—EGM 1—2016, checked on 15 November 2017.

Excelsior. (2017). Los nuevos lectores de Excélsior; es un referente. Claudia Solera, Marlene Urban. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://www.excelsior.com.mx/nacional/2017/03/27/1154273

García, D. (2013). Sentiment during Recessions. The Journal of Finance, 68(3), 1267–1300.

González Dulanto, C. (2016). Análisis de sentimiento en Internet para decisiones estratégicas. Retrieved June 4, 2017, from https://www.iit.comillas.edu/pfc/resumenes/5049b5878939e.pdf

Herman, E. S., and Chomsky, N. (2008). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. London: Bodley Head.

Infobae. (2017). Trump, a Macri: Espero que Argentina y EEUU tengan la mejor relación de su historia. Retrieved September 9, 2017, from http://www.infobae.com/politica/2016/11/14/trump-a-macri-espero-que-argentina-y-eeuu-tengan-la-mejor-relacion-de-su-historia/

Informador. Mx. (2016). Peligran 10 millones de empleos sin EU en TLCAN. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.informador.com.mx/economia/2016/695570/6/peligran-10-millones-de-empleos-sin-eu-en-tlcan.htm

Informador. Mx. (2017a). México saldría del TLC; Donald Trump anuncia hoy el muro. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.informador.com.mx/economia/2017/703901/6/mexico-saldria-del-tlc-donald-trump-anuncia-hoy-el-muro.htm

Informador. Mx. (2017b). México puede prosperar sin Trump: Zedillo. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.informador.com.mx/mexico/2017/704470/6/mexico-puede-prosperar-sin-trump-zedillo.htm

Informador. Mx. (2017c). México y EU viven “momento de definición” de relaciones: SRE. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.informador.com.mx/mexico/2017/712721/6/mexico-y-eu-viven-momento-de-definicion-de-relaciones-sre.htm

Informador. Mx. (2017d). Trump rectifica: EU pagará por muro y México lo reembolsará. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.informador.com.mx/internacional/2016/688112/6/trump-rectifica-eu-pagara-por-muro-y-mexico-lo-reembolsara.htm

Instituto Federal Electoral. (2014). Catálogo Nacional de Medios Impresos e Internet 2014, checked on 15.11.2017.

La Nación. (2017a). Trump dijo que reforzará la frontera y ratificó su política proteccionista. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1977858-trump-dijo-que-reforzara-la-frontera-y-ratifico-su-politica-proteccionista

La Nación. (2017b). Donald Trump quiere fijar un impuesto de 20% a las importaciones mexicanas para pagar el muro. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1979275-donald-trump-quiere-fijar-un-impuesto-de-20-a-las-importaciones-mexicanas-para-pagar-el-muro

La Nación. (2017c). Donald Trump y Enrique Peña Nieto sellan un “pacto de silencio” por el muro. Retrieved June 1, 2017, from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1979828-donald-trump-y-enrique-pena-nieto-sellan-un-pacto-de-silencio-por-el-muro

La Nación. (2017d): El desplante de EE.UU. a la CIDH, otro síntoma de los problemas que enfrenta el organismo. Retrieved June 3, 2017, from http://www.lanacion.com.ar/1996984-el-desplante-de-eeuu-a-la-cidh-otro-sintoma-de-los-problemas-que-enfrenta-el-organismo

Liu, Bing. (2012). Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining, 22 April 2012, checked on 07.07.2017.

Moreyra, R. D. (2017). Boletín IVC—Argentina (940)—September 2017, checked on 15.11.2017.

Mullen, T. (2004). Introduction to Sentiment Analysis, checked on 20.09.2017.

Perfil. (2017). Macri y Trump: el renacer del periodismo (I). Retrieved July 10, 2017, from http://www.perfil.com/columnistas/macri-y-trump-el-renacer-del-periodismo-i.phtml

Piñeiro, M. G. (2011). ¿Por qué falla el análisis de sentimiento? Retrieved June 4, 2017, from http://www.concepto05.com/2011/03/por-que-falla-el-analisis-de-sentimiento/

Reporters Without Borders. (2017a). World Press Freedom Index 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2017, from https://rsf.org/en/ranking.

Reporters Without Borders. (2017b): Mexico: Constant Violence and Fear. Retrieve July 7, 2017, from https://rsf.org/en/mexico.

Retegui, L. (2017). La construcción de la noticia desde el lugar del emisor. Una revisión del newsmaking. RMOP 23, 103.

Robinson, P. (Ed.) (2001). Theorizing the Influence of Media on World Politics. European Journal of Communication 12, 16(4), 523–544.

Stecher, A. (2010). El análisis crítico del discurso como herramienta de investigación psicosocial del mundo del trabajo. Universitas Psychologica, 9(1), 93–107.

Tetlock, P. C. (2007). Giving Content to Investor Sentiment: The Role of Media in the Stock Market. The Journal of Finance, LXVIII(3). Retrieved from https://www.valuewalk.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Tetlock_JF_07_Giving_Content_to_Investor_Sentiment.pdf

Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. (2017a). Trump busca fijar impuesto de 20 % a importaciones mexicanas para pagar muro. El Tiempo—El Periódico del Pueblo Oriental. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://eltiempo.com.ve/mundo/politica/trump-busca-fijar-impuesto-de-20-a-importaciones-mexicanas-para-pagar-muro/235315

Tiempo, Casa Editorial El. (2017b). Negociando con el lobo. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from http://www.eltiempo.com/opinion/negociando-con-el-lobo-tlc-de-estados-unidos-con-colombia-76848

van Dijk, T. A. (2003a). La multidisciplinaridad del análisis crítico del discurso: un alegato en favor de la diversidad. Retrieved June 2, 2017, from http://www.discursos.org/oldarticles/La%20multidisciplinariedad.pdf

van Dijk, T. A. (2003b). La multidisciplinariedad del análisis crítico del discurso: un alegato en favor de la diversidad. pp.143–177. Retrieved May 31, 2017, from http://www.discursos.org/oldarticles/La%20multidisciplinariedad.pdf

Wang, H., Yin, P., Zheng, L., and Liu, J. N. K. (2013). Sentiment Classification of Online Reviews: Using Sentence-Based Language Model. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved September 17, 2017, from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0952813X.2013.782352

Zhitomirsky-Geffet, M., David, E., Koppel, M., and Uzan, H. (2016). Utilizing Overtly Political Texts for Fully Automatic Evaluation of Political Leaning of Online News Websites. Online Information Review, 40(3), 362–379.