The Strategic Partnership between Brazil and the EU

Nelia Miguel Müller

Introduction

Since the ratification of the Lisbon Treaty and the enhancement of the EU common foreign policy, also new forms of interregional arrangements have emerged. The term “strategic partnership” was introduced to EU vocabulary in 1998, when Russia was called a strategic partner (European Council, 1998). Since then the concept was reinvented after the modifications due to the Lisbon Treaty. It even became a policy priority in 2010, when the European Council was asked to choose “key partners” in order to “strengthen the EU’s ability to project its influence in the world” (European Council, 2010).

Today the EU maintains 10 bilateral and 5 regional strategic partnerships. The regional arrangements are mainly older cooperation agreements with regional groupings such as NATO, Africa and the African Union, and CELAC. There are 10 bilateral partnerships with single countries. Considering the original meaning of the term “bilateral,” these arrangements cannot be labeled as bilateral relations, as the EU is not a federal state. For a clearer distinction between the different interregional arrangements and to stress the partnership character with single states, those agreements are called bilateral partnerships in the following. Even though the starting point of some partnerships is not transparent, a trend is noticeable considering the latest partners chosen for collaborations. From 2003 onward, the EU established partnerships with emerging countries playing a significant role in global economy and in their respective region (Brazil, India, South Africa, and Mexico) (Grevi and Khandekar, 2011; Schmidt, 2010).

Although the EU has put a lot of effort in collecting its strategic partners, the conceptualization of those arrangements is vague and differs in each partnership. Neither an official European definition, nor a uniform catalogue of rights and duties is available. The only official documents are the country-specific “Action Plans,” which are lacking for some strategic partnerships (SP) arrangements. However, strategic partnerships are an increasingly used term, expressing a declaration of interest without any binding character. Consequently, confusion about behavior and result expectations within the relationship, which is deemed strategic, can dominate cooperation and reduce the possibility of a tangible output.1

Those arrangements are heavily criticized in the research literature for being futile. The argument mainly focuses on the low outcome generated. These authors emphasize the mismatch between expectations and reality, based on studies evaluating the past years (Grevi, 2013; Lazarou and Fonseca, 2013; Smith, 2013). Furthermore, a causal relation between the establishment of a strategic partnership and the improvement of relations is difficult to confirm. The EU’s strategic partnership with the United States is, for instance, generating a decent outcome, but there is no evidence of a causal relation, that is, that the partnership would not work if there was no SP. However, a certain euphoria, especially at the beginning, can be observed in most partnerships.

Taking this into consideration, it is questionable, whether this recent foreign policy is an efficient policy concept. In the case of the European Union, the answer might be no. As a clear definition and concept is missing, none of the involved actors puts forward any idea about the meaning and practice of being a strategic partner. Therefore, the chance of decent results becomes unlikely. Furthermore, the number of strategic partners hinders a coherent strategy. Having 10 bilateral and 5 regional partners, makes it difficult to find arrangements suitable for all actors or at least not contradictory ones. Due to overlap of bilateral and regional agreements, hierarchical questions emerge. If the declarations with South Africa and the African Union contain contradictory objectives, which one is more important? Shall South Africa stick to the bilateral SP or follow the aims of the regional partnership?

From these observations the central puzzle of this chapter emerges: As the strategic partnership concept does not seem to have a tangible impact or a clear meaning, why do states have an interest in becoming strategic partners? What are the crucial motives? What type of relationship is established? Does it fit the concept of interregional relations? Those questions shall be addressed in this chapter. The aim is to understand and explain the nature of strategic partnerships, its motives, and implications. Although the relevance of strategic partnerships is viewed with skepticism in the literature, the emergence of those relationships cannot be ignored and actually deserves further attention.

This chapter focuses on one bilateral strategic partnership, Brazil-EU. However, examples from other cases are used too. The Brazilian case was chosen due to the importance of that South American country and its closeness to the European Union in terms of values and historical ties, which may influence a partnership in a positive sense. Strategic partnerships with regional groupings were excluded from analysis as they would almost invariably fit the pure interregionalism with varying degrees of success and sustainability. The chapter unfolds as follows. First it provides an overview of Brazil-EU relations. Then it dissects the motives behind this strategic partnership. An analysis of the substance and impact of the partnership follows. A final section on the Brazil-EU strategic partnership as a paradigmatic case of new trends in interregionalism precedes the concluding remarks.

Brazil-EU Relations

Brazil was one of the first countries worldwide, and the first Latin American country, that established diplomatic relations with the European Economic Community—the predecessor of the European Union—in 1960 (Ceia, 2008). Regarding political cooperation, Brazil and the EU have a long tradition of partnership, founded on cultural proximity and the same values. Especially the importance of a strengthened multilateralism and a strong United Nation, as well as the respect for human rights were defined as common key objectives (Brazil-European Union Summit, 2008). Even Brazil’s wish to gain a permanent seat at the UN-Security Council is to some extent backed by the European Union contrary to what happens in other world regions as for instance Latin America or Asia.

Having established diplomatic relations only three years after signing the Treaties of Rome, it took another 32 years for a further institutionalization of Brazil-EU political cooperation. With the signing of the EC-Brazil Framework Cooperation in 1992, the bilateral relation gained official character and included regular meetings. Although Brazil-EU diplomatic relations were recorded in an official agreement in 1992, only little progress has been made since then. A bilateral joint commission, which should strengthen a diplomatic cooperation, was started, yet their relations only gained momentum in 2007, when a strategic alliance was formed (Itamaraty, 2017). At the first EU-Brazil summit in July 2007 in Lisbon, the heads of state and government decided to establish a joint strategic partnership. This was a further step toward deepening interregional cooperation between Brazil and the European Union.

Laura Ferreira-Pereira explains the declaration of interest between Brazil and the European Union primarily in historical terms. She stresses that the Portuguese EU-Council Presidency was one of the key reasons for the creation of an EU-Brazil partnership. Ferreira-Pereira argues that it was Portuguese activism, which promoted the key position of Brazil long before the economic take-off had started (Ferreira-Pereira, 2010). Taking the initiative of creating a closer relation to a former ally or colony is typical of EU member states. Especially France has acted similarly and established strong relations with the ACP states or—more generally—to former French colonies.

The strategic partnership between Brazil and the European Union marks the beginning of an interregional relationship between two significant actors: Since the Treaties of Rome, the EU has established a huge variety and amount of interregional arrangements, varying from trade and economic relations to political dialogue, development and security cooperation (Langenhove, 2011). Brazil, is the largest and strongest economic actor in the South American region, as well as an emerging power and member of the BRICS (see Stolte in this volume). Despite its current financial and political crisis, Brazil has huge economic potential and more positive forecasts have been reported recently.

Trade and economic cooperation is of great importance on both sides, pushing their relation forward. As trade tripled within the last decade from 30 billion USD in 2000 to 97 billion USD in 2012 (Megiato et al., 2016), bilateral trade relations between Brazil and the EU have become of major importance. From 1990 onward, the EU as a regional bloc has been the most important trading partner for Brazil, but the EU share is declining with China’s rising influence in this region. Although China is slowly replacing the EU’s position, the specific amount of EU-Brazil trade is still significant, especially in the sector of industrial or manufactured products. Compared to China (5% import of manufactured goods), the EU received a five times higher amount of Brazilian manufactured products (26%) in 2015. Furthermore, the European Union has one of the major stocks of foreign direct investment in Brazil. With approximately 50% of foreign investment in Latin America going to Brazil, the EU is the fifth largest direct investor (European Commission, 2017). The already profound economic potential allows opportunities for further expansion, especially within the strategic partnership arrangement, which is focused on many areas,2 including trade relations.

Motives

In this section, the motives of Brazil and the European Union will be further investigated as well as the implications that arose out of the creation of a strategic partnership. The measurable output of the strategic partnerships in general is rather modest, which raises the question why the involved parties are still interested in this partnership. Is there a hidden benefit or did expectations simply not meet the reality? Are there theoretical concepts, which may help explaining the creation of a strategic partnership?

In the discipline of International Relations (IR), several theoretical approaches try to explain why states establish or strengthen relations with others. In order to explain the motives of the EU and Brazil, I will employ a combination of neorealist and neoliberal institutionalist approaches. Such a framework has already been used in similar contexts and promises a better understanding of cooperation motives. Neorealist approaches argue that cooperation takes place to ensure one state’s power and security. Therefore, states cooperate to accumulate power and influence (Morgenthau, 1993; Waltz, 1979).

Cooperation can be explained—using an institutionalist approach—with the growing interdependency and the wish of promoting a certain order (Friedrich, 1968). In this sense, states seek cooperation in areas of interest to pursue their goals. They seek institutions for establishing a normative order, because they cannot reach this alone. According to institutionalist scholars, this form of cooperation may even extend due to the growing complexity of the international system, political processes, and the rise of new actors (business companies, non-state actors).

With the elaboration of a strategic partnership, the European Union and Brazil pursued different aims, according to their respective position and interests. Whereas some aims are joint, or at least similar ones, there may also be some motives, which differ significantly between the two actors. While the EU is composed of developed, high income countries, Brazil still considers itself as a developing country. Derived from their respective position in the international economy and the international system, they have different expectations on the interregional arrangement.

For both Brazil and the EU, there seem to be two major motives; these are the improvement of both economic and political relations. The first EU motive addresses its economic position. As one of the biggest economies in the world, solid foreign economic relations are essential. Therefore, in the official documents, the strengthening of economic cooperation and the increase of bilateral trade are emphasized (Brazil-European Union Summit, 2008). Since Brazil offers a huge variety of resources and agricultural and manufactured products, it may be an interesting trading partner for the European Union. Although China has already overtaken the EU as Brazil’s most important trading partner, the EU seems to have a huge interest of not falling far behind. In 2016 1.7% of the EU’s total import came from Brazil, with a decreasing tendency (European Commission, 2017). However, in 2015 21.4% of all Brazilian imports came from the member states of the European Union (World Trade Organization, 2016). This makes Brazil an important sales market for European products, which should be tied closer to the EU.

The creation of open trade relations and a more investment-friendly environment can be mentioned as key objectives, under the consolidation of economic ties. Brazil cannot be considered as a huge trading nation that is promoting free trade (WITS, 2015). In fact, Brazilian elites pursue a rather protectionist economic policy making it difficult for foreign investors to engage in this complex country. Considering the amount of 30.4 billion Euros, the EU has invested in 2014 in Brazil (European Commission, 2017)—which is far more than in any other BRICS-state—implies a strong interest in Brazil and may explain the wish for creating a more open trade and investment environment in Brazil.

Economic motives seem also to be one of the major drivers for Brazil’s interest in the strategic partnership. Although Brazil has a rather protectionist view considering international trade, it achieves huge benefits from fostering the economic cooperation with the European Union. By doing so, Brazil is not only getting an easier access to one country, but to 28 member states of the EU. Since 17.8% of Brazil’s total exports are going to EU member states (World Trade Organization, 2016), Brazil could gain an economic advantage in strengthening economic relations. Although Brazil is not a huge trading nation (WITS, 2015) and is not necessarily dependent on exporting goods to the European Union (huge domestic consumer market and diverse trade partners, for example, China), the loss of almost 20% of all exports could be harmful for a country in the middle of an economic crisis. Therefore, the interest of keeping or even improving the existing economic relations may be huge on the Brazilian side, in order to keep its position internationally.

Especially bilateral economic cooperation between Brazil and single EU member states can be of major interest. While putting an increased focus on knowledge transfer, especially the industry sector in Brazil can benefit from this interregional cooperation. This goes hand in hand with the enlargement of EU investment in Brazil. With the implementation of various joint projects, Brazil already benefits a lot. One example is a German-Brazilian project that uses the weather in the Amazonian rainforest to forecast storms.

In addition to economic motives, the EU also pursues political objectives. Brazil’s growing importance and the target of strengthening the EU’s international profile match together well. According to Antônio Carlos Lessa, the reasons for this bilateral agreement are based on two facts: First, Brazil’s growing international profile, and secondly, the stagnation in EU-Latin American talks. Lessa argues that the main problem leading to a stagnation was the perception of a Latin American homogeneity. A perception which does not match the region’s profile, and which created some irritation in EU-Latin American relations (Lessa, 2010). The growing global presence of Brazil aroused the interest of international actors, including the European Union, which views its strategic partnership with Brazil as an opportunity to benefit from good relations to an emerging power.

The creation of an effective multilateralism can be mentioned as one of those political motives the EU pursues by maintaining an interregional arrangement with Brazil. Although it is never well defined, what is meant by the term “effective multilateralism,” it often appears in the official documents of the strategic partnership. Multilateralism appears to be an important instrument for the EU to deal with security challenges like terrorism or climate change (see Koschut in this volume). Therefore, it can be claimed that cooperation in international fora and the strengthening of the United Nations constitutes a core motive for building strategic partnerships. The Action Plans reveal a quantitative cluster of the term “effective multilateralism” in the Brazil-EU partnership. This specific aim is mentioned more often than in other partnerships, which can be a hint for being of major importance for both actors.

In order to foster multilateral cooperation, Brazil could act as a kind of bridge-builder between the Global North and the Global South. Brazil is a country which maintains stable relations with both developing countries and developed powers from the northern hemisphere. The fact that Brazil is not exclusively cooperating with either group makes it an interesting partner for the European Union and may allow the recruitment of new partners. The EU has concluded strategic partnerships with all of the BRICS states. This implies an at least nascent interest in establishing profound relations with these emerging powers. The remaining question is the motive behind that action, that is, whether this has been an ad hoc decision, due to growing economic figures in the BRICS states, or part of a long-term strategy to build ties with future global players.

The concept of Europe as a normative power (Manners, 2002) should also be mentioned in the context of the EU political motives. This approach argues that the EU has a specific interest in exporting and establishing its norms in other regions via economic relations and financial incentives (Whitman, 2011). Among the export of norms, the European Union is also trying to promote its integration model to other regions. Megiato et al. argue that a bilateral engagement between Brazil and the EU may also have a positive impact on MERCOSUR integration. Through cooperation with MERCOSUR members, the EU tried to implement its integration model in Latin America (Megiato et al., 2016). So, one of the political motives can be the transfer of the European integration model to Latin America. Yet, due to the heterogeneity of the region and its aversion to relinquishing national sovereignty, this does not seem to work (Gardini, 2012; Lessa, 2010).

In addition to economic motives, Brazil seems to pursue one further goal: international status recognition. Brazil suffers from a certain kind of inferiority complex (Stolte, 2014) and wants to gain higher status in the international system. The EU’s choice of picking Brazil as key player in the South American region, symbolizes a certain recognition of Brazil’s importance in the region and among the emerging powers. A strategic partnership implies a special relationship, different from non-partners. The combination of one or two important players in each world region could give the impression of a global interregional network created by the EU. The recognition of Brazil as the power house of the South American region and the EU’s invitation to its special circle of strategic partner needs to be interpreted as a rise in global status. This may serve as a plausible explanation for Brazil joining the club of strategic partners.

Both the EU and Brazil can be considered “actors in transition” in a changing international environment (Gratius, 2013). Whereas Brazil tries to raise its status in the international system, the EU may fear a loss of its status due to internal crises and its decreasing importance at the international level. As both share to a large extent the same values and to a lesser but still significant extent a similar preference of power distribution (multilateralism)—at least according to official statements—there is room for coordinated actions. This implies a mutual motivation for further cooperation to play a more substantial role in international affairs. However, one of the remaining questions is, whether both aims of gaining more (Brazil) and preventing a loss of status (European Union) may be fulfilled with the same means.

Expectations were high on both sides of the Atlantic when the strategic partnership agreement was signed. Although the motives differed, they could be clustered around—broadly speaking—economic and political motives in order to strengthen their respective position. The concept of a network creation around key-players—defined by economic or political power within their region—seemed to be an attractive concept. Taking this into consideration, and resuming discussion on IR theory, a combination of both (neo)realism and liberal institutionalism capture both the EU’s and Brazil’s main motivations behind their strategic partnership. Both actors strive for a more influential role internationally and were looking for maximizing their benefits. Considering only the realist approach however would be too limited and one-sided, as both actors seem to be interested in promoting a common idea of multilateral order as well as their preferred values and norms. Whether the interest in creating a genuinely multilateral and fair order was the main objective or rather a mean to increase influence and power remain an open question.

In any case, the measurable outcome of interregional arrangements is usually quite low. So why are both actors still engaged in the agreement? One answer may be that strategic partnerships do not aim at purely material and measurable outputs. The motive of being recognized as an important, emerging power (Brazil) or a normative power shaping the international political landscape (EU) can hardly be measured in quantitative terms, but is more about the status-related recognition by other powers. The remaining question is whether this expectation can actually be fulfilled through the strategic arrangement.

Substance and Impact

Almost 10 years after the strategic partnership between Brazil and the EU took effect, the outcome is still modest. Since the establishment of this partnership, two joint action plans have been concluded and a lot of cooperation aims have been defined. However, only few cooperation projects have been implemented. The huge amount of cooperation aims and a lack of policy priorities may be reasons for the ineffectiveness of this partnership agreement so far.

The defined cooperation areas cover a vast quantity of different subjects. Whereas some objectives tackle the strengthening of economic relations—as for instance the expansion of trade (in terms of diversification and volumes)—others pursue a joint support for solving issues like international power distribution, upcoming global challenges, development questions, or social welfare. A classification in two major policy fields can be observed: On the one hand, a deeper cooperation targets economic areas, like investment and knowledge transfer. On the other hand, we can also observe a wish for more coordination on broadly speaking political dialogue, like regional integration projects or reforms of the international system.

Each Action Plan has a life span of three years and needs to be revised after this time. However, it remains unclear whether the defined aims must be fulfilled by or after the expiry date. A comparison of the two Action Plans reveals a significant similarity between the two documents, whereby only a few paragraphs regarding climate change and environmental cooperation were added to the latter draft. These affinities notwithstanding, the second action plan is much longer and detailed: Its length passed from 18 to 28 pages in the period between 2008 and 2011 (Brazil-European Union Summit, 2008; Council of the European Union, 2013). It is debatable whether this really is an advantage or makes the whole Action Plan less accessible and more bureaucratic.

However, the postponing of a new Action Plan and the delay of some summit meetings may undermine the importance of the strategic partnership. Although both actors were enthusiastic when establishing the agreement, already the Second Action Plan has been delayed (from 2011 to 2013). The third one, which was expected for 2016 is announced for late 2018. The postponing or cancellation of the presidential summit meetings for the last three years (2015, 2016, and 2017) have been decided because of internal issues both in Brazil and the EU. This behavior shows that the strengthening of cooperation is not a priority. The last presidential annual summit took place in 2014. For the period between 2015 and 2017 no annual meeting was held. Economic summits and sectoral dialogues yet proceed regularly.

The two existing joint action plans define the common aims and the scope for deeper cooperation: (1) promoting an effective multilateral system; (2) economic, social, and environmental cooperation; (3) regional cooperation; (4) science, technology, and innovation; and (5) promoting a people-to-people exchange. Those categories contain various subtopics for each of the five cooperation areas. For reasons of analytical clarity, four examples of the common objectives will be analyzed against their generated outcome.

The first category, the promotion of multilateralism, contains alone more than 10 different tasks. Among these are the support for democratic structures and the respect for rule of law, trilateral cooperation (especially in Portuguese speaking countries in Africa and Asia), the reform of the United Nations, disarmament and nonproliferation, conflict prevention, fight against terrorism, and organized crime. Both signatory parties agreed that those are essential areas in which better cooperation may help promote an effective multilateral system (Council of the European Union, 2013).

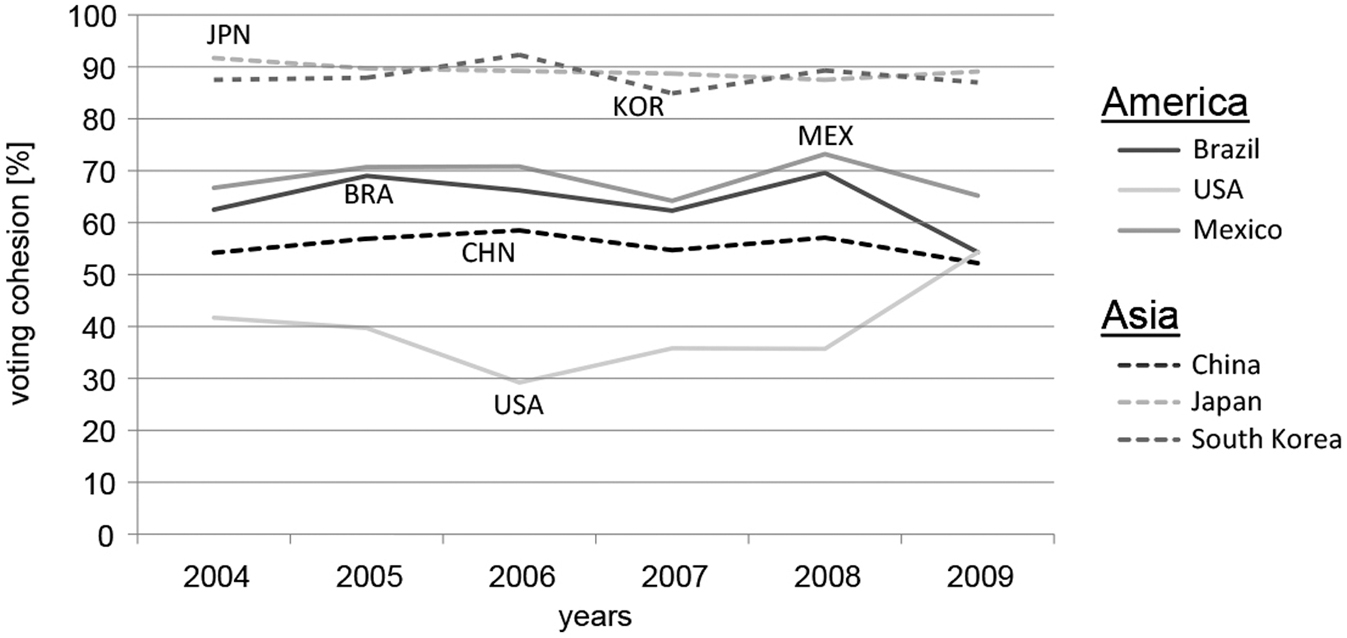

In order to face upcoming challenges and to take up more responsibility in the international system, both Brazil and the EU agreed on harmonizing their voting behavior in international fora, like the United Nation. Yet, their voting behavior in the UN General Assembly shows that this goal has not translated into political action so far. An evaluation of voting behavior in the General Assembly reveals a low voting cohesion between Brazil and the European Union.3Figure 4.1 shows that states like Japan or South Korea are voting more consistent with the EU than Brazil, although a harmonization of votes was defined as priority aim for the strategic partnership. Also Mexico, the other strategic Latin American partner of the European Union, shows a bigger voting cohesion in UN bodies than Brazil. Even more striking is the decrease in voting cohesion between Brazil and the EU since 2007 regardless of the discussed topic (see Figure 4.1 for voting cohesion years 2004–2009). Although voting cohesion is slightly better in topics related to security issues, others—like Development and Human rights—show an even worse pattern.

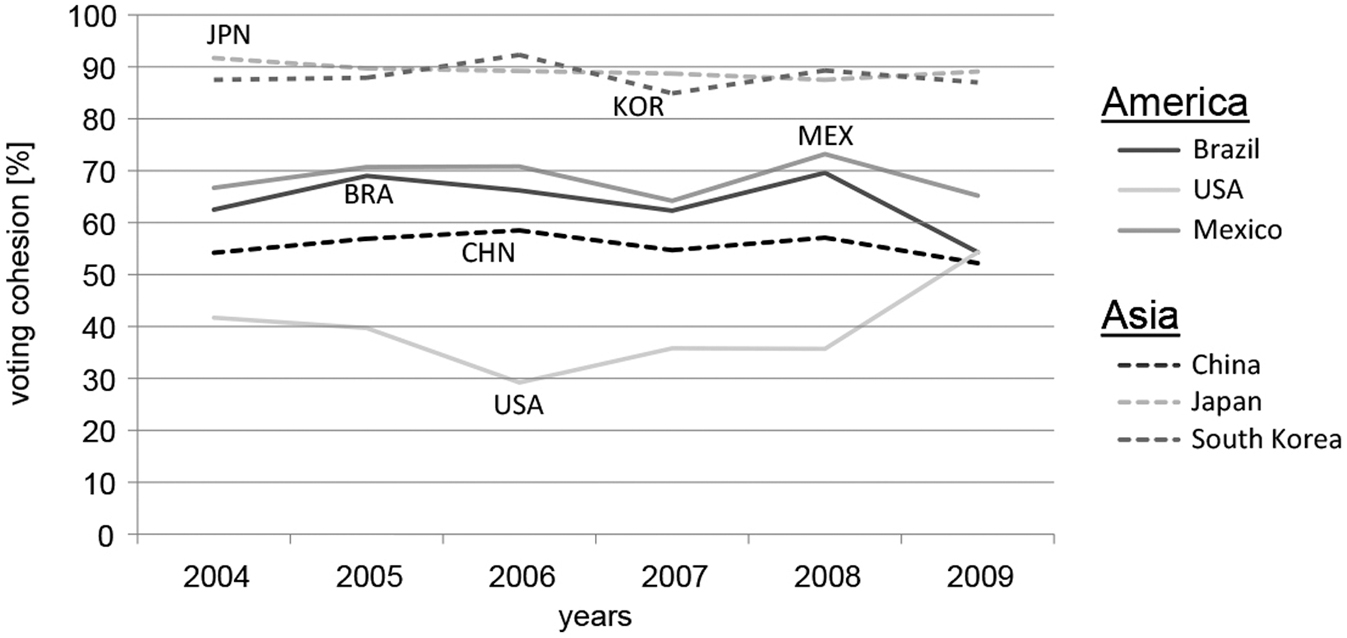

The second category or objective is economic and trade cooperation. Although trade between Brazil and the EU increased since the implementation of the partnership, a clear causal relation cannot be proven. As Figure 4.2 shows the total amount of trade has grown—except for the period between 2009 and 2010—which is a result of the EU financial crisis and the resulting decline of trade. However, trade only expanded slightly, and other trade partners played a more significant role for both parties, especially for the EU. China, for instance, has become one of the major trading partners for both actors (WITS, 2016). What is also interesting is that especially Brazilian exports toward the EU did increase, while the tendency the other way was much lower. Therefore, it seems to be the South American partner who benefits more from the strategic partnership.

That said, a clear causal relationship between the increase of trade and the strategic partnership is unlikely, due to two reasons: First, trading conditions and regulations have not changed with the strategic partnership. Secondly, trade relations have existed since the 1800s and have already shown bigger increases and shift than nowadays. Therefore, the slight increase after 2007 may be explained with the initial euphoria of the SP, but trade increase may more likely be caused by external factors (prices, demand etc.). The only trade-relevant factor that can be linked to the SP is the yearly business summit, where important business representatives from both partners come together. Yet, the specific influence of those talks on the growth of trade volume, need to be further analyzed.

Figure 4.1 Voting Cohesion with EU in UN General Assembly. Source: www.unbisnet.un.org, author’s figure.

Regarding the third area, sustainable cooperation, ambivalent findings can be observed: While the planning of cooperation projects seems to be working, their implementation runs into difficulties. As a matter of fact, most cooperation projects are implemented by Brazil and one individual member state on a bilateral basis (Valladão, 2008, Ferreira-Pereira, 2010). Even previous projects initially involving more EU partners either have been canceled or have been reduced to a limited number of involved parties. A new cooperation project between Brazil and six EU member states, which has been launched in June 2017 promises good results (project “BeCool”). This project targets the production of biofuel and may have a positive impact on the Brazilian production of biofuels. The coming years will have to show how successful such a cooperation project can be.

The fourth area seems to be an objective and a means to reach some of the common aims at the same time: political dialogue. To reach a strengthened cooperation, both actors defined institutionalized meetings at the presidential and ministerial level as desirable. Both agreed on the importance of annual and sectoral dialogues for ensuring a working cooperation. Additionally, these dialogues should lead to a harmonized negotiation strategy in international fora on the long-term. So far, a dialogue structure has been implemented, which includes more than 30 meetings per year (presidential meetings, ministerial dialogue, business summit, civil society round tables, and sector policy dialogues on an ad hoc basis). This shows the willingness to cooperate and strengthen bilateral relations. However, considering the high financial costs for these meetings and the low generated output (see the conceptual chapter by Gardini and Malamud in this book), a less enthusiastic evaluation may be appropriate. The postponement of meetings in the last years shows the decreasing importance of the partnership in turbulent times. Both actors are occupied with solving current domestic issues, like economic and political crises (refugee, impeachment, BREXIT, etc.).

To sum up, based on four cooperation examples, the actual and tangible output of the strategic partnership has been presented. In most cases, the measurable outcome is modest; common aims did not translate into joint actions. However, a discussion over common strategic aims has been started and institutionalized with regular meetings and summits. This is a positive political result per se. Perhaps, Brazil and the EU may revise the very concept of their strategic partnership and may want to aim for relatively smaller, more focused, and self-contained objectives—at least for an initial period in order to consolidate the mechanism and give it substance.

Figure 4.2 Trade between Brazil and the EU (total goods). Source: European Commission, 2017, author’s figure.

The Brazil-EU Strategic Partnership—A Paradigm for Hybrid Interregionalism

Based on globalization processes, regions became more important and came closer together, introducing the possibility of relations between new actors, that is regions as unitary political actors (Söderbaum, 2013). Consequently, the number of interregional arrangement increased during the last century. The strategic partnerships of the European Union are cases in point for the increasing importance of different types of interregional arrangements.

According to the classification of interregional relations provided by Hänggi et al. (2008), three different forms of interregional arrangements exist: (1) relations between regional groupings, (2) bi-regional or transregional arrangements, and (3) hybrid forms. The first category represents the interaction between two regional associations. The EU’s strategic partnerships with regions—for instance the arrangement with Africa and the African Union—are defined as relations between regional groupings (Hänggi et al., 2008). The second form, defined as transregional arrangements, is usually based on economic cooperation and they are typically heterogeneous and large. According to Hänggi (2000), there are five transregional arrangements so far, among one of them is the APEC—which includes 21 Pacific Rim, 15 East Asian, and 5 American countries. Finally, there are hybrid forms of interregional relations. Those arrangements focus on relations between regional groupings and single countries in other regions of the world. Usually these single powers have a dominant position in their respective region (Hänggi et al., 2008).

The 10 strategic partnerships of the European Union with single powers, among them the EU-Brazil arrangement, can be characterized as hybrid forms following this typology. Although these partnerships do not have a binding character but represent a mere declaration of intent, they nevertheless institutionalize contacts between a regional grouping and a single state. The 2007 agreement replaced the prior instrument (1992) of governing relations between Brazil and the European Union. While the earlier relationship can already be interpreted as an interregional link, the 2007 partnership agreement institutionalized previous contacts and gave the relationship a legal framework. It was established on a solid legal basis (Art. 21–22 of the Lisbon Treaty) and created at least a rudimentary form of institutionalized cooperation in various areas (European Union, 2007).

From a linguistic perspective, the term “strategic partnership” can be compared to the former meaning of the words “allies” or “partners” (Kay, 2016). This implies a special relationship, presumed that all states without SPs do not count as EU allies. Taking this into consideration, the strategic partnership offers a special form of interregional relationships. It highlights the global strategy of the EU to collect important partners from different regions for implementing a strengthened cooperation. Yet, apart from the collection of partners, a clear objective for cooperation is still missing. As shown in the Brazil case, the motivation to form a strategic partnership was high but did not result in any significant output. In fact, the measurable outcome is very modest and reveals a mismatch between claim and reality.

However, a certain institutionalization of relations was reached with the agreement. The establishment of regular dialogue fora on different levels gave the partnership a permanent character. This lifted previous ad hoc cooperation to a relationship with regular meetings and organized discussions about cooperation. If this institutionalization did not lead to measurable output, this is of lesser importance as the regularity of the meetings is already part of the strategic goal. Being forced to define common objectives and their implementation is one of the first steps toward a real institutionalized partnership. The need for defining common aims and a regular discussion starts a dialogue, which may lead toward further cooperation projects.

These findings are consistent with the conceptual framework of this book, mentioning that dialogues and summits are important elements for interregional relations, no matter what and if results are generated (Gardini and Malamud, 2016). The dialogues are not only one of the defined aims in the strategic partnership, but they are also a core element of it. Besides the fact that this sector is the only area where cooperation really works—in terms of generating output—it made the relationship more stable and gave it a more durable character.

Making Brazil the only South American partner of the European Union shows a recognition of Brazil’s role internationally but also in its own region. The EU defined Brazil as its main target, together with Mexico, in Latin America and further succeeded in breaking Brazil’s “Latin America-complex.” Furthermore since 1999 the Union has tried to reach deeper cooperation—in form of a FTA—with MERCOSUR without success. This change or complementation of strategy—from MERCOSUR to Brazil through hybrid interregionalism—shows perhaps a better understanding of political circumstances in South America. The European integration model cannot be transferred to a region because of different political, cultural, and economic circumstances. Hence, a different, more focused but perhaps less compelling interregional framework may offer more opportunities for cooperation. The attempt of targeting specific countries in several world regions, may be a shifted focus in EU foreign strategy and may result in more success than previous attempts did.

Conclusion

This chapter analyzed the motives and consequences of the bilateral strategic partnership between Brazil and the European Union. Motives were clustered into economic and political and were similar for each partner. Nonetheless the achieved results are still modest. Although the aim of the SP was to foster all types and areas of cooperation, the only institutionalized part of the SP is the establishment of regular dialogue forums and mechanisms. This area is also the most productive part of the partnership and generates visible and tangible output. However, due to internal issues on both sides, the regularity of those meetings suffered in the last few years, which may reduce the SP between Brazil and the EU to a marginal foreign policy tool.

As a relationship between one regional grouping and a single state, the SP fits the hybrid form of interregionalism. Although Brazil-EU relations do not mean high levels of integration, the SP can certainly be understood as an example of interregionalism with specific characteristics. Some cooperation areas were identified as areas of special interest, thus creating a certain output. The summitry exercise envisaged in the partnership agreement lifted the status of EU-Brazil relations and cooperation from an ad hoc basis to a regular, more institutionalized form.

So, after 10 years of being in force, did the strategic partnership fail to deliver? Having analyzed the motives and consequences of the Brazil-EU case, this question remains open. In terms of creating measurable results, the partnership did fail and expectations did not meet reality. As shown, in almost no policy field measurable outcomes were generated. Only in the area of sustainable development some results have been achieved. Yet, those cooperation projects have been implemented bilaterally, meaning between Brazil and EU member states. Measurable results from EU-Brazil cooperation activities are still lacking.

However, the strategic partnership did redefine the bilateral relationship between Brazil and the European Union. The establishment of the SP in 2007 constitutes a breakthrough in EU-Latin American relations. As the EU-MERCOSUR negotiations went on for almost 20 years with ups and downs but did not result in a formal agreement, a new approach was needed. The strategic partnership is an answer to this need. Although the term “strategic partnership” is rather loosely used by the EU, this agreement broke the stagnation and acknowledged Brazil as an important partner for pursuing Europe’s international interests. The creation of a bilateral agreement gave the topic of EU-Latin American relations a new momentum. With Brazil becoming a strategic partner of the EU, the EU not only acknowledged the growing importance of Brazil but it also diminished previous asymmetries in their relation. In the agreement, no formal junior or senior partner can be observed. It seems more as a partnership between equals. Furthermore, it is essentially the EU that is pushing for a deeper cooperation. Brazil has plenty of other options (China, BRICS, MERCOSUR, and other regional schemes). The EU instead seems to be in need of partners like Brazil to sustain and possibly improve its international profile.

The definition of common aims as part of the Action Plans and the launch of regular dialogue meetings can be interpreted as a step toward a strengthened bilateral partnership. Although concrete results are still modest, a dialogue about key challenges and objectives has been started. It has the potential of fostering the relationship between the EU and Brazil and create a more integrated and substantial strategic partnership. However, this will need time and effort. Most of all, political will and interest on both sides, are decisive factors for the future of the strategic partnership.

NOTES

1. Considering the amount of uncertainty and confusion, there is no differentiation between bilateral and bi-regional SP agreements.

2. The areas covered by the SP are further explained in the subchapter “Motives.”

3. Due to the voting rules in the UN General Assembly, the EU is not allowed to vote as whole. Only those cases where the EU member states voted in a consistent way were analyzed. Although this reduces the number of cases, this was the only possibility of examining voting cohesion in a methodologically credible way.

References

Axelrod, R., and Keohane, R. (1993). Achieving Cooperation under Anarchy: Strategies and Institutions. In D. Baldwin (Ed.), Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate. New York: Columbia University Press, 85–115.

Brazil-European Union Summit. (2008). Brazil-European Union Strategic Partnership Joint Action Plan, Rio de Janeiro.

Ceia, E. (2008). The New Approach of the European Union towards the Mercosur and the Strategic Partnership with Brazil. Studia Diplomatica, LXI(4), 81–96.

Council of the European Union. (2013). Second Brazil-European Union Strategic Partnership Joint Action Plan, Brasilia.

European Commission. (2017). Trade. Countries and Regions. Brazil. Retrieved April 23, 2017, from http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/brazil/

European Council. (1998). Presidency Conclusions. Vienna.

European Council. (2010). Conclusions. Brussels.

European Union. (2007). Treaty of Lisbon Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community. Lisbon.

Ferreira-Pereira, L. (2010). As relações entre a união europeia e o Brasil: o papel de Portugal num processo em crescendo cooperativo. Mundo Nuevo: Revista de Estudios Latinoamericanos, 1(3), 9–30.

Gardini, G. L. (2012). La UE: ¿Un modelo o una referencia para la integración en América Latina? In G. Arenas Valverde, and H. Casanueva (Eds.), De Madrid 2010 a Santiago 2013: Evaluación y Perspectivas para la Agenda Estratégica Unión Europea—América Latina y Caribe. CELARE-UPV, Santiago de Chile, 36–43.

Gratius, S., and Grevi, G. (2013). Brazil and the EU: Partnering on Security and Human Rights? Fride Policy Brief, No. 153.

Hänggi, H. (2000). Interregionalism: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. Paper prepared for the Workshop “Dollars, Democracy and Trade. External Influence on Economic Integration in the Americas.” Los Angeles, CA, May 18.

Hänggi, H., Roloff, R., and Rüland, J. (2008). Interregionalism and International Relations. Abingdon: Routledge.

Itamaraty. (2017). European Union. Retrieved August 14, 2017, from http://www.itamaraty.gov.br/en/ficha-pais/6698-european-union

Gardini, G. L., and Malamud, A. (2016). Debunking Interregionalism: Concepts, Types and Critique—With a Transatlantic Focus. Atlantic Future Working Paper (38).

Grevi, G. (2013). The EU and Brazil: Partnering in an Uncertain world? In M. Emerson, and R. Flores (Eds.), Enhancing the Brazil-EU Strategic Partnership: From the Bilateral and Regional to the Global. Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies, 198–216.

Grevi, G., and Khandekar, G. (2011). Mapping EU Strategic Partnerships. Madrid.

Kay, S. (2016). What is a Strategic Partnership? Problems of Post-Communism, 47(3), 15–24.

Langenhove, Luk van. (2011). Building Regions: The regionalization of the world. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Lazarou, E., and Fonseca, C. (2013). O Brasil e a Uniao Europeia: a Parceria Estratégica em busca de signifocado. In A. Lessa, and H. Lessa (Eds.), Parcerias Estratégicas do Brasil: os significados e as experiencias tradicionais. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traco, 91–117.

Lessa, A. (2010). Brazil’s Strategic Partnerships: An Assessment of the Lula Era (2003–2010). Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 53, 115–131.

Manners, I. (2002). Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms? Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(2), 235–258.

Megiato, E., Massuquetti, A., and Azevedo, A. (2016). Impacts of Integration of Brazil with the European Union through a General Equilibrium Model. Economia, 17(1), 126–140.

Morgenthau, H. (1993). Politics among Nations. The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: McGraw-Hills.

Schmidt, A. (2010). Strategic Partnerships—a Contested Policy Concept. SWP Working Paper FG 1, 2010/07, Berlin.

Smith, M. (2013). Beyond the Comfort Zone: Internal Crisis and External Challenge in the European Union’s Response to Rising Powers. International Affairs, 89(3), 653–671.

Söderbaum, F. (2013). Rethinking Regions and Regionalism. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, 14(2), 9–18.

Stolte, C. (2015). Brazil’s Africa Strategy: Role Conception and the Drive for International Status. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Valladão, A. (2008). L’UE et le Brésil: un partenariat naturel. In Grevi, G., and Vasconceles, A. (Eds.), Partnership for Effective Multilateralism: EU relations with Brazil, China, India and Russia. Paris: EUISS.

Waltz, K. (1979). Theory of International Politics. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Whitman, R. (2011). Normative Power Europe: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

WITS. (2015). Brazil Trade Summary 2015 Data. Retrieved May 25, 2017, from http://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/BRA/Year/LTST/Summar