In the first days of excitement after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the press was full of stories of volunteer troops assembling, mustering and drilling in anticipation of war service. None was more prominent than the “Washington Brigade.” The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on April 16 that the Washington Brigade was busily engaged in recruiting and drilling at Ladner’s Military Hall, a militia rendezvous and beer hall at Third and Green Streets, an area inhabited by many German and Irish immigrants. There was great excitement at these headquarters. General William F. Small, the commander, was expected to take his troops to Washington that week; the brigade had been accepted for service by the War Department. Military Hall was crowded to overflowing with volunteers, and new organizations were forming for immediate service. The officers all expressed their ability to be ready to move by the close of the week.51

About midnight on Friday, April 19, the Washington Brigade, consisting of two regiments—the 1st Regiment “Monroe Guards,” with six companies of American-born volunteers, and the 2nd Regiment, “Washington Guards,” composed of five companies of German immigrants totaling close to 1,200 men—along with the 6th Massachusetts Regiment, which had arrived the previous evening en route for Washington, had departed by train for the capital. They were met with an enthusiastic reception as they entrained at the Broad and Prime Street Station. A short time before departure of the train containing the Philadelphia Volunteers, the Massachusetts militiamen had left the Girard House and marched to the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Depot (hereafter PW & B) and boarded the cars for Washington behind the Philadelphians. The train left Philadelphia for Washington via Baltimore. The Massachusetts regiment was uniformed and well equipped, but the Philadelphians were mostly not uniformed and unarmed. While crossing the Susquehanna River at Perryville, Maryland, the Massachusetts militia was shuttled to the front of the long train, displacing the Philadelphians. The 6th Massachusetts, therefore, reached Baltimore in the lead cars and exited first and, while marching from one depot to the other, was obstructed by an angry mob of Secessionists. In the fight that ensued, four Massachusetts soldiers were killed and dozens were wounded; a number of civilians were likewise left dead after the troops were forced to fire into the crowd. Estimates of the dead reached over 25 civilians. The troops, however, managed to reach the Camden Street Station and passed on southward.

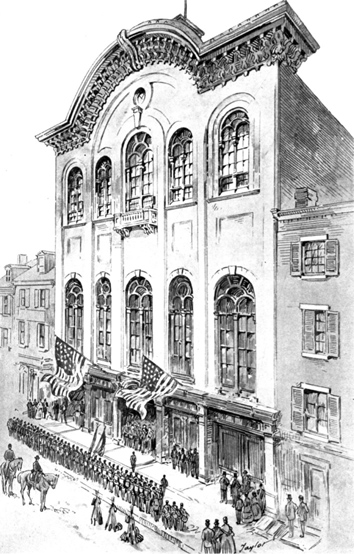

National Guards Hall. A sketch showing the armory of the National Guards militia on Race Street below Sixth Street (now the site of the National Constitution Center). GAR Museum Collection.

The Philadelphia companies were left in the rear cars. They were stoned inside the cars by the angry mob. In his report of the affair, General Small stated that his Pennsylvanians behaved gallantly and many sprang from the cars upon their assailants and engaged in hand-to-hand combat with them. It was impossible, however, to distinguish friends from foes, as the mob was composed of a mixture of Union men and Secessionists who were fighting among themselves. The Pennsylvanians could not be distinguished from the citizens. Lack of proper weapons made retaliation futile, and one volunteer, George Leisenring, a young German immigrant from Saxony, then residing in the Northern Liberties–Kensington section, was so severely stabbed while sitting in his car that he died a few days later in Pennsylvania Hospital, becoming the first Philadelphia and Pennsylvania fatal casualty of the war.52

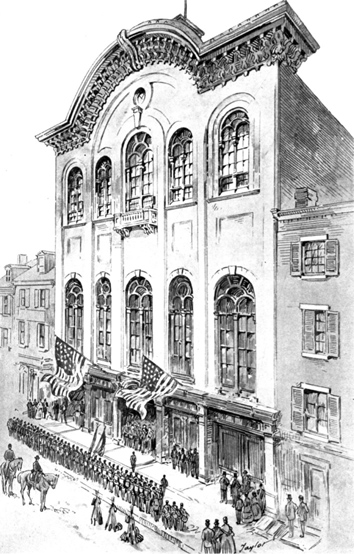

Depot of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad. A sketch showing the main depot of the PW & B Railroad, the major avenue for transportation to points south and toward the warfront. GAR Museum Collection.

Pennsylvania Hospital at Eighth and Spruce Streets. It is the oldest hospital in America, founded in 1751. It treated the first casualties of the war and witnessed the first death of a Philadelphia volunteer. GAR Museum Collection.

The officers and men, Small added, conducted themselves with the utmost courage. He stated that even regular army troops could not have behaved better. A majority of the Washington Brigade returned on the night of April 19, reaching the depot at Broad and Prime Streets after eleven o’clock. Twenty-eight members of the force became separated from the rest of the command, and according to the statement by Samuel Baker, a volunteer, after fleeing northwest about twenty-two miles from Baltimore, his group was arrested by some Secessionists. They were marched across the county to Bel Air, Maryland, and placed in jail. They suffered threats of bodily harm and even hanging. On the following day, however, they were released and escorted by local militia to the Pennsylvania line, from where they proceeded to Philadelphia.

In order to avoid further bloodshed, the chief of police at Baltimore had urged the men to return home to Philadelphia. Philadelphians, upon learning of this outrage, were incensed. Several days later, the Buena Vista Guards, one of the companies that had been attacked, presented to city councils a “Rebel” flag that they had captured in the Baltimore riot.53 After this experience, Northern soldiers were sent south via steamer around Baltimore, the route being Havre de Grace to Annapolis to Washington.

The Baltimore riot caused intense resentment in Philadelphia and called forth strong expressions of indignation from most citizens. The event increased activity at the recruiting stations, and enlistments grew after the attack.54 Philadelphia now devoted itself, with characteristic energy, to the duty of providing the government with soldiers properly armed and equipped as fast as they were needed. In the course of the war, the city was represented in nearly 150 regiments, battalions, batteries, cavalry troops, independent units and other detached units (including emergency troops not called outside of the state), the majority of which were raised entirely locally. In addition, many Philadelphia companies served in commands of other states, as well as thousands of sailors, marines and regular army recruits.55

The effect of war upon business in Philadelphia in the early months of the struggle was a source of great anxiety among larger employers. At the establishment of Matthias W. Baldwin & Co., where 80 locomotives had been built in the preceding year, matters were nearly at a standstill. Many of the workers had been discharged, and plans were considered for turning the plant into a factory for shot and shell. Unexpectedly, however, the national government ordered many engines, and the “war railroads” required many more. Between 1861 and 1865, Baldwin turned out 456 locomotives, many of them the heaviest and most powerful ever constructed.

At the shipyards, machine shops, textile mills and factories of all types, government contracts soon afforded abundant employment. Philadelphia workmen were able to provide heavy and light artillery, swords, rifles, camp equipage, uniforms and blankets in great quantities. This activity continued throughout the period of the war.56

During the early months of the war, many Philadelphians were eager to enlist. In the Fourth Ward of the city, Captain William McMullen, a staunch local Democratic politician and Irish immigrant who had served in the Mexican War, was organizing a group of one hundred picked men as rangers, or scouts. A young merchant, wealthy and well educated, came to him and begged to be permitted to join the group even as a private. Because the ranks were already filled, the captain agreed to accept him if at the next drill some recruit would resign. Accordingly, the following day the young man presented himself at the drill field and first offered $25, then $50, and then $100 to anyone who would resign, thus permitting him to march with Captain McMullen. Not a man stepped forward to accept the proposal, and the disappointed patriot finally was informed by a sergeant in the group that even $1,000 would be insufficient to purchase the place of the poorest in the company—so enthusiastic were they all to take part in the conflict.57

Because so many of the volunteers enlisted without making adequate provision for their families while they themselves were absent in the service, a petition was submitted to the residents of the wards of the city in which everyone was invited to record subscriptions for the relief or employment of volunteers’ families. Not only was aid given to recruits from the city itself, but it was also tendered to volunteers who entered from other parts of the state. Soon after Lincoln called for recruits, the Young Men’s Christian Association offered its mammoth tent, which it used for the purpose of holding public worship and was conveniently situated on Broad Street near the Academy of Music, as a reception center and temporary accommodation for troops in transit through the city.58

To help volunteers who arrived in Philadelphia, and who had not been mustered into service, John B. Budd, of 1317 Spruce Street, offered to furnish daily at noon a dinner to ten or twelve men who otherwise would have had difficulty in obtaining food. To prevent imposition, this worthy gentleman required a written order from the captain or commander of the respective regiments or companies of which his hungry guests would soon become members.59

From the amount of pay received monthly by the majority of volunteers, and later by drafted men, it is little wonder that many left behind them families dependent upon public or private relief. The monthly pay for a private in 1861 was thirteen dollars per month, plus food, clothing and equipment. The officers were required to provide their own uniforms and equipment. So that every soldier might enjoy clean attire, the North American newspaper suggested that each company going into service should take along washerwomen, if the men wanted clean clothes.60 According to paragraph 124 of the U.S. Army regulations, each company was entitled to four washerwomen who were allowed one ration a day, and in addition to this compensation for any washing they did, they were entitled to a small salary paid by the officers and men.

Not to be outdone in patriotic activities by their husbands and brothers, many Philadelphia women volunteered to sew for the national government. At the Girard House Hotel, which Governor Curtin chose for a military depot, as it was then standing vacant due to the competition of the more popular Continental Hotel across Chestnut Street, a notice was posted stating that women were needed to sew uniforms. In the Girard House, the government established a military clothing depot under the supervision of Robert L. Martin, assisted by Captain George Gibson. It was expected that one thousand garments a day could be produced, including such articles as underwear, sack coats, greatcoats and trousers. Here, as well as at the Schuylkill Arsenal, women were employed sewing uniforms on piecework, but many fashionable ladies also offered their services, especially in those early days when uniforms were desperately needed.61

After the first Philadelphia troops left for Washington on that fateful Thursday and early Friday morning, April 18 and 19, a number of businessmen met in the Board of Trade rooms to discuss the organization of a company for the military defense of the city. At that time, it was thought that many of those who enrolled would eventually go into active service wherever they were needed even though the terms of enrollment related only to service in the city. Of the approximately fifty men who joined at this first meeting, the majority were merchants and professionals within the legal draft limit, or under forty-five years of age. They were men who felt unable to leave the city immediately for distant service.

Quickly formed, this organization became known as the Home Guard and was increased to include every adult male not needed elsewhere and not physically disqualified. Immediately, agitation commenced in every ward of the city to organize a Home Guard unit within each one’s respective limits. According to the authority conferred on him by councils, on April 20, 1861, Mayor Henry appointed Colonel (later General) Augustus J. Pleasonton to be commander of the Home Guard with the rank of brigadier general of volunteers.62 General Pleasonton was authorized, under the direction of the mayor, to organize his force into various units of cavalry, artillery and infantry.

The Home Guard Medical Department was placed under the supervision of Dr. John Neill, and Moyamensing Hall was equipped to serve as a hospital not only for sick and wounded members of the Home Guard but also for all such men in the United States service.63

Various groups joined the guard in a body, among them the Maennerchor Vocal Society of Philadelphia, composed of Germans. This group, under the command of Captain John A. Koltes, a veteran of the Mexican War, was organized as a rifle company and prepared for active service as part of the Home Guard.64

The uniform for the guard consisted of a single-breasted frock coat of cadet gray with a standing collar and buttons of the branch of service to which the regiment belonged; the pantaloons were made of the same material as the coat. The cap, cut on the army pattern, was of drab color, trimmed with a rosette of red, white and blue. Regiments of “young guards” were allowed to substitute the cap for the regulation army hat. These uniforms, many of which were provided by the members themselves, cost from six dollars to twenty dollars, depending upon the financial status and personal taste of the individual. The uniforms were to be worn habitually so that in case of alarm the officers and men could dash at once to their armories without stopping to change their clothes.

In order to enable the Home Guard to become more proficient in military duties, a number of Philadelphia merchants agreed to close their businesses at four o’clock in the afternoon each business day of the week with the exception of Saturday, when they would close at three o’clock for the period between April 15 and July 15, 1861. This was done so that their employees might have an opportunity to drill and obtain military training.

Although the Home Guard was maintained during the entire four years of the war, its activity depended upon the threat of danger from Rebel invasions. This occurred several times, and at the Battle of Gettysburg, a number of companies of the Home Guard were mobilized to defend their state from the enemy.65