The most benevolent and generous of the many civic organizations formed for the assistance of the soldiers and alleviation of their sufferings during the Civil War was the United States Sanitary Commission, which originated with a group of military and civilian men and women in New York City, led by the Reverend Henry W. Bellows. This association was given official status by the secretary of war on June 8, 1861, and later by Congress.114

Branches of the commission were formed in every large Northern city. Large donations of money and supplies were constantly placed at the disposal of the commission, coming from every corner of the loyal states. The officials and committees volunteered their time and served without pay. The Sanitary Commission undertook the collection and forwarding of supplies and comforts to the troops at the front and assisted in the relief work among the sick and wounded, especially after battles. A general hospital directory was published by a Bureau of Information, located in Washington, in order to enable friends and relatives to find soldiers in the army hospitals. A claim’s agency and pension agency were maintained without cost to the soldiers.

More than forty Soldiers’ Homes were established, having a daily average of 2,300 patients. Hospital inspectors constantly visited every segment of the army. Hospital trains were operated by the Sanitary Commission over the railroads, and hospital ships were employed on the seas. As far as possible, the commission supplied food, medicine and clothing to prisoners of war held in the South.115

In Philadelphia, the local branch was located at 1307 Chestnut Street and received large monetary donations, as well as supplies, 80 percent of which was sent outside the city. The local commission also provided a “lodge” at Thirteenth and Christian Streets for the support and shelter of soldiers.116

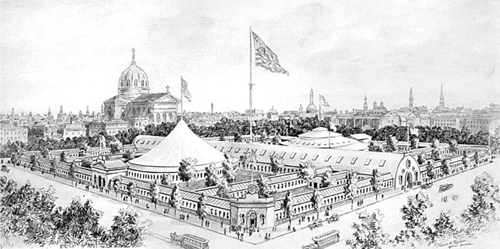

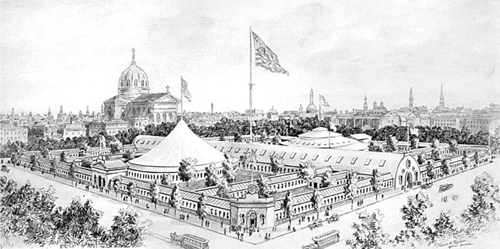

Many organizations for soldiers’ relief in Philadelphia united to sponsor the Great Central Fair on behalf of the Sanitary Commission in June 1864. This Great Central Fair was probably the greatest purely civic act of voluntary benevolence ever attempted in Philadelphia. To assist the work of the Sanitary Commission, large fairs were held in all the great cities of the North. Philadelphia’s fair was held in an enormous temporary building covering the whole of Logan Square (now Logan Circle). Many of the large businesses and commercial houses and all of the street railway companies contributed one day’s receipts, and many workers donated a day’s pay to the project. With the funds obtained, the immense building was erected, with its booths, smoking lounge, picture galleries and brewery. To stock the booths and galleries, thousands of contributors poured their treasures into the structure. The fair opened on June 7 and remained open until June 28. The governors of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware participated in the opening ceremonies, and President and Mrs. Lincoln and son Tad visited the fair on June 16, 1864. After his visit, President Lincoln was hosted at a dinner held by the members at the Union League at the first League House at 1118 Chestnut Street. After the fair closed, all remaining articles were sold at auction. The fair not only proved very attractive but was also immensely successful, raising the enormous sum of $1,261,822.52, which was donated for the general work of the Sanitary Commission to aid in soldiers’ relief.

Great Central Fair. A sketch from Harper’s Weekly showing the Great Central Sanitary Fair on Logan Square, held in June 1864. The Great Central Fair was held to raise funds for the benevolent work of the Sanitary Commission. GAR Museum Collection.

According to Charles J. Stille, who wrote a memorial history of the fair for the Sanitary Commission, “This great hall had all the vastness of the Cathedral’s long drawn aisles and its moral impressiveness as a temple dedicated to the sublime work of charity and mercy.” Various “departments” were organized along the corridors of this city of mercy.117

Local businesses, individuals and institutions donated their products, services and valuable items to sell or raffle to support the patriotic cause, and the fair exhibited a wide array of goods, artifacts and curiosities, all under one gigantic roof. A magnificent collection of paintings was loaned by private collectors and museums, filling the northern corridor. A great variety of displays and amusements were provided to entice visitors.

The cost of the undertaking was largely derived from popular subscriptions and donations.118 Over the several weeks of the fair, more than 250,000 visitors were recorded at an admission price that varied from fifty cents to one dollar.

The New Jersey and Delaware Branches of the Sanitary Commission were also involved and invited to participate in the noble work.

An exciting aspect of the fair was the ongoing competition to vote for favorite generals then serving in the field and to raffle off valuable treasures to raise additional funds. As the fair progressed, the voting was continually announced based on the purchase of a ballot, allowing the purchaser to cast a vote for each item. Even the generals noted the competition and commented on the contest.119 At the conclusion of the fair, the results were announced and the prizes awarded. Voting results announced the following winners: General Meade was the winner of the magnificent sword with 3,442 votes out of a total 5,541. General Hancock won the horse equipments with 116 votes out of 212. General Birney won the camp chest with 308 votes out of a total of 385. The silver vase was won by Mr. Edward D. James, a citizen, with 4,939 votes. The imported leghorn ladies’ bonnet was won by Mrs. General Burnside with 296 votes, with Mrs. General Meade a close second with 285 votes.120

Another important organization for relief work during the Civil War was the Young Men’s Christian Association of Philadelphia, which began its operations almost simultaneously with the operations of the armies of the United States at the outset. It soon ceased to be a merely local organization and developed into the United States Christian Commission. At first its headquarters were in New York, but they were removed to Philadelphia in 1862 and remained there during the war. During the four years of the war, large sums of money and an enormous amount of supplies were disbursed by the commission.121

On November 15, 1861, delegates from fourteen branches of the Young Men’s Christian Association met in New York City and organized the commission, electing George H. Stuart, a distinguished citizen of Philadelphia, as permanent chairman. Philadelphia, therefore, became the center of the national movement for the moral and spiritual welfare of the soldiers. Of the nearly five thousand agents of the commission eventually sent to the army, the first group was composed of fourteen members of the Philadelphia association.

For a long period, the government army officers and many of the chaplains tolerated, but did not heartily assist, the commission’s agents. Authority to visit and work among the soldiers was officially granted in some instances and refused or revoked in others.

Along with its moral message, the commission began to provide material comforts, especially to the sick and wounded. In November 1863, an arrangement was made with the Confederate authorities that enabled the commission to send food, medicine and clothing to Union prisoners of war. It was not until September 1864 that an order was signed by General Grant giving the representatives of the Christian Commission full privileges in the camps of the army.

In the years of its existence, the commission performed much benevolent work. The Philadelphia offices of the Christian Commission were located at 1011 Chestnut Street, where assistance was given to soldiers, sailors and visitors seeking relatives in the hospitals. During the war years, the local YMCA also provided a large tent on Broad Street near the PW & B station for the use of the army recruits and volunteers on the way to the warfront. The Christian Commission established cordial relations with the United States Sanitary Commission, and they cooperated in the cities, camps, on battlefields and on the seas—in fact, everywhere—in the important work to which both organizations were devoted. The officers of the Christian Commission were George H. Stuart, president; Joseph Patterson, treasurer; and Reverend W.E. Boardman, secretary.122

During the war, numerous patriotic and benevolent associations were founded in Philadelphia. Many of them were connected with the churches, while others were of secular origin, but all provided some form of assistance to the soldiery of the Union cause. The services of a large proportion of the devoted men and women cannot be adequately estimated. In some instances, printed reports were made, copies of which have been preserved, and these afford an outline of many helpful deeds these groups accomplished.

The Women’s Pennsylvania Branch of the United States Sanitary Commission was organized on February 25, 1863. The special work of this grass-roots organization of women was the relief of soldiers’ dependents and the gathering of supplies for the men in the field.123

Probably the first local association of women who “wanted to help” was the Ladies’ Aid Society of Philadelphia, which was organized in April 1861 “to provide garments for soldiers, work in hospitals and take care of soldiers’ families.” Its mission covered a broad field of patriotic services, and it did excellent work in furnishing volunteer aid and supplies both locally and to those serving in the field. Those most active were Mrs. Joel Jones, president; Mrs. Stephen Colwell, treasurer; and Mrs. John Harris, secretary.124

The women of Philadelphia were so eager to find beneficiaries among the soldiery that the whole country was not too large. For instance, the ladies of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church sent, in May 1861, nine hundred pairs of shoes to the Union Missouri Volunteers.125

In December 1861, the Soldiers’ Relief Association of the Episcopal Church was formed. On July 28, 1862, a number of ladies met at the office of Edward Brady, Esq., 135 South Fifth Street, and formed the Ladies’ Association for Soldiers’ Relief. Mrs. Mary A. Brady became president and Mrs. M.A. Dobbins treasurer. At first, this association devoted its efforts to providing special dinners to the occupants of the local army hospitals. Later, it seems to have made a specialty of the Sixth Corps. One of the most successful relief expeditions that ever went out of Philadelphia, from the soldiers’ point of view, was welcomed in the camps of those Philadelphia warriors when Mrs. Brady and her associates appeared one day at the front with a wagonload of good plug and smoking tobacco. The ladies of this association hastened to the bloody fields of Antietam and Gettysburg and there, amid sickening surroundings, imitated the English nurses who had, but a few years before, followed Florence Nightingale to the Crimean War. On May 27, 1864, Mrs. Brady died at her home, 406 South Forty-first Street in West Philadelphia, as a result of her persistent labor in the cause to which she had been so long devoted.126 The Penn Relief Association was founded “to assist sick soldiers in and out of hospitals and to aid their families.” The officers and Executive Committee included many women who belonged to the Society of Friends.127

The first institution in the United States to receive and care for children of men who had enlisted, and of deceased soldiers, was the Northern Home for Friendless Children and Associated Institute for Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Orphans, located at Twenty-third and Brown Streets. This institution was aided liberally through the efforts of Mrs. Elizabeth Hutter and by Dr. Albert G. Egbert, a wealthy oil operator of Mercer County, Pennsylvania. Over 1,300 children of soldiers were housed and educated at this home. After the war, General Meade took an active role in the support of the institution and its educational program.128

The Lincoln Institution was founded in order to provide a home for the sons of soldiers who had fallen in battle. General George G. Meade was active in this charity and became its first president. The institution was located on Eleventh Street, below Spruce.129

After the war, in 1873, the Educational Home for Friendless Boys was opened at Forty-ninth Street and Greenway Avenue. It was a branch of the Lincoln Institution and was later merged with it and became part of the Pennsylvania Orphans’ School system. At these well-conducted homes, hundreds of boys were educated and sustained while learning trades and sent out into the world well equipped to be successful citizens. At a later period, the management admitted Indian boys and girls to both institutions.

A modest but popular enterprise of war days in Philadelphia was the Soldiers’ Reading Room maintained, for several years, on Twentieth Street below Market Street, in a building formerly the Brickmakers’ Baptist Church. Here soldiers were always welcome to come and rest, read and relax. The organization was a precursor to the future USO of more modern times. A considerable library of books, magazines, games, files of newspapers from many cities and writing material, a piano and a smoking room were at the free disposal of all soldiers and sailors. Hot lunches were provided for five cents, or without charge if occasion required. Lectures were given in the evenings, and religious services were offered on Sundays. The average attendance was about one hundred soldiers per day.130

The Ladies’ Association of West Philadelphia was active in raising money for soldiers’ families. Prominent ladies involved were Mrs. John Cotton, Mrs. Thomas Hunter, Mrs. John Sweeney and other ladies of distinguished families.

The Union Temporary Home was established to provide a shelter for the children of soldiers in the field of men who had enlisted.

In 1864, the Ladies’ First Union Association was active, with rooms at 537 North Eighth Street, in feeding and providing for a large number of the families of soldiers.131

Among other groups founded by patriotic organizations wishing to lend material and spiritual support for the soldiers and sailors and their families were the Freemasons’ Soldiers’ Relief Association at 204 South Fourth Street, the New England Soldiers’ Relief Association on Chestnut Street near Thirteenth and the Hebrew Women’s Aid Society. The free black community of Philadelphia also formed similar groups to assist the colored volunteers, their families and recently freed slaves from the South. These included the Colored Women’s Sanitary Commission, with headquarters at 404 Walnut Street. The distinguished officers were Mrs. Caroline Johnson, president; Mrs. Arena Ruffin, vice-president; Reverend Stephen Smith, treasurer; and Reverend Jeremiah Asher, secretary, who later served as chaplain of the 6th U.S. Colored Troops and died in service. There were also the Colored Union League and Freedmen’s Relief Association. Many of these volunteer service organizations continued their work to the close of the war and even into the postwar period.132