After many months of seemingly endless war and ever larger casualty lists, many citizens had begun to grow weary. This emboldened certain disloyal elements in the city, largely from the conservative fringe of the Democratic Party, who began to openly support the Southern rebellion and worked actively against the war effort and the Lincoln administration. Some of these individuals belonged to the social elite of the city. This disturbing situation was discussed and addressed by a group of prominent, loyal citizens. They decided to meet and invite other loyal men to gather at the residence of Mr. Benjamin Gerhard, at 226 South Fourth Street, to promote the formation of an organization whose purpose was to support the Union, its preservation and the war effort. This group was quickly dubbed the Union Club. Referring to this group years afterward, George H. Boker, a founder, wrote:

So timid and hesitating was the beginning of the Union Club that the notice to certain gentlemen to meet in Mr. Gerhard’s house seemed to contain no authority for the assemblage. The receivers of the notes of invitation were informed merely that there would be a meeting of loyal men for a patriotic purpose. There was no signature to these notes, and from the context one might have inferred that Mr. Gerhard, had abandoned his house to the use of his friends.159

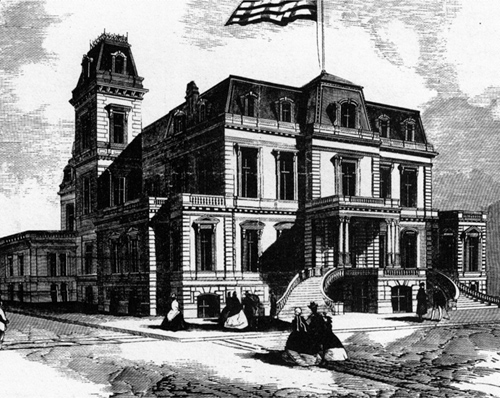

A sketch of the newly opened Union League House in May 1865. The Union League still uses the same edifice, though expanded over the years, located at 140 South Broad Street. GAR Museum Collection.

Several meetings were afterward held at private homes, and these meetings seemed to revive the historic Wistar parties instituted by Dr. Caspar Wistar in his home on South Fourth Street in 1798. At one of these early meetings, held at the residence of Dr. John F. Meigs on December 27, 1862, the title of the “Union League” was adopted for use of the group, which had grown considerably. The first formal meeting of the Union League was held in Concert Hall at 1219 Chestnut Street on January 22, 1863.160

In the meantime, the former residence of Mr. Hartman Kuhn, at 1118 Chestnut Street, had been leased by the league for use as its headquarters. (This house, which afterward became the Baldwin Mansion and still later Keith’s Theater, stood on the site now occupied by a row of modern shops.) According to reports, the members kept a supply of sturdy hickory axe handles on hand for use in the defense of the League House and possibly also against Rebel soldiers should they enter Philadelphia.161

The first elected president of the Union League was William Morris Meredith, then serving as attorney general of the state. The membership had grown to 536 members by 1863.162 The first League House was opened to members on February 23, 1863, and the Union League immediately became a powerful center of support for the Union cause and war effort. In fact, a national movement was launched based on the Philadelphia Union League’s mission and resulted in the creation of hundreds of similar leagues throughout the loyal states. After the war, they were revived by the freedmen and their supporters and established in the South. This was received with contempt by many of the former Southern Confederate supporters, and these loyal leagues became prime targets of the Ku Klux Klan and other anti-black groups.

Union League Memorial Tablet. A sketch of the memorial in the hall of the Union League House commemorating the units raised by the Union League for Civil War service. GAR Museum Collection.

One of the first committees formed by the Union League was the Military Committee, which was established to raise funds to assist in the recruitment, organization and equipping of volunteer units for army service. The members of the committee formed a virtual who’s who of the socially prominent Union men who were in support of the military and the Union. Many had sons and relatives then serving in the armed forces.163

As an inducement to secure recruits, the Union League offered a bounty of $300 to each volunteer soldier, expending funds on bounties totaling hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In early June 1863, league members met and agreed to form a committee to assist in the recruitment of Colored Troops. As a result, a large number of league members formally petitioned the government for permission to raise black regiments. Thereafter, the army established Camp William Penn, just beyond the Philadelphia city line, where African American volunteers from the region were gathered to train and organize under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Louis Wagner of the 88th Pennsylvania Volunteer Regiment. Wagner became an active member of the league after the war. The Union League, through its Military Committee, assisted in this enterprise by spending over $33,000 on equipment, uniforms, bounties and support for their families. Each regiment at muster into Federal service was presented with a stand of colors also funded by the league.164

Many prominent civic leaders supported the wartime activities of the Union League, and especially the effort to recruit Colored Troops. Frederick Douglass, the best-known black abolitionist, was often a guest of the league and gave impassioned speeches there in support of its work. Douglass spoke effectively on July 1, 1863, during the Gettysburg emergency when the first colored volunteers were enlisting.165

During the period of the war, the Publication Committee also issued many patriotic circulars and pamphlets in support of the war, as well as the Union League Gazette, of which 560,000 copies were printed and distributed.166

The Union League also supported veterans by caring for sick, wounded and disabled men and their families after their discharge and establishing a bureau to assist them in finding employment. This effort continues unabated to the present time through the work of the Armed Services Council.

On May 11, 1865, the Union League moved into its new house at 140 Broad Street, which it has occupied to the present time.167

A bronze tablet placed in the corridor of the Union League House and two bronze figures of soldiers stand on pedestals in front of the Union League building on South Broad Street as memorials to the veterans’ of war service in the history of this influential and patriotic organization.168