Sometime after the outbreak of the Civil War, a proposal was made that the city should prepare for the danger of a possible attack. Accordingly, a few small defensive earthworks were erected at various defensible places, but they were never occupied by troops. They were situated as follows: a redoubt on the hill in East Fairmount Park at the intersection of the main drive from Lemon Hill and Girard Avenue; at the head of the Girard Avenue Bridge (the embankments were leveled at the close of the war); a small half-moon artillery redoubt on the north side of Gray’s Ferry Road, between the Schuylkill Arsenal Depot and the Schuylkill River, on the eastern side; a redoubt on the rocks formerly known as the Cliffs, on the west side of the Schuylkill, near the end of the railroad bridge at Gray’s Ferry (the fort and the rocks were eliminated by the railroad after the war); an earthwork on the north side of Market Street west of the Schuylkill River, on the rise of the hill west of Thirty-sixth Street; an earthwork on Chestnut Street (south side) east of the junction with Darby Road; and an earthwork on Lancaster Avenue near Hestonville, West Philadelphia.203

During the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania in June 1863, a real threat existed to Philadelphia. Accordingly, a Committee of Defense was authorized by city councils to establish fortifications for defense and improve those that had already been started, defending the principal approaches to the city from the west. The positions of these earthworks were determined by officers of the United States Coast Survey stationed in Philadelphia under Professor Alexander Dallas Bache.204

They were located as follows: on the south side of Chestnut Street, east of the junction of Darby Road, east of the Schuylkill River, near the Schuylkill Arsenal; west of the Schuylkill River, below Gray’s Ferry Bridge; at the east end of Girard Avenue bridge; in Hestonville, near Lancaster Avenue; and on School House Lane, above Ridge Avenue in East Falls. The largest of these works, located at the falls of the Schuylkill and known as Fort Dana, was created by a force of seven hundred city workers from the gasworks, as well as volunteers from the vicinity and the clergy.205 Fort Dana was constructed during the panic caused by Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania at the end of June and into early July 1863. It was the largest of the several redoubts hurriedly built to protect the city. No guns were ever mounted, as the threat receded after the Battle of Gettysburg, though two two-hundred-pound Parrott cannon were ordered. No names were given to the other works.206

The danger ended with the Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg and repulse of the Confederates. Several of the redoubts remained for a number of years after the war as reminders of the strenuous and, as some critics thought, unnecessary labors of the public, which had been panicked at the time.

After the war, the projecting bluff where Fort Dana had been constructed was quarried for stone and was slowly removed, though the position can be imagined if one visits the present site on the campus of Philadelphia University near the old Ravenhill Academy.207

The following were the federal arsenals and installations where military weapons, ordnance, uniforms and equipment were manufactured and stored.

The Frankford Arsenal is located along the Delaware River and Frankford Creek in the Bridesburg section. It was opened in 1816 on 20 acres of land purchased by the federal government. The grounds originally contained 2 stone buildings but later grew to over 234 buildings on 110 acres at its heyday during World War II. During its long history, it served as nerve center for U.S. military ordnance, shells, cannonballs and small-arms ammunition design, manufacture, research and development until its closure in 1977. The old arsenal was sold in 1983 and is now a private business park.208

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the arsenal’s commander was Captain Josiah Gorgas, a native of Pennsylvania. He soon resigned in deference to his Alabama-born wife and joined the Confederate States Army and was promoted a brigadier general and chief of ordnance. In May 1861, when an effort was made to equip several three-month or ninety-day regiments from stores contained at the Frankford Arsenal, the officers protested at the antiquated, unusable muskets offered to their men.209

At the end of the Civil War, the arsenal employed over one thousand workers. It served as a major site for the storage of weapons and artillery pieces and a depot for the repair of artillery, cavalry and infantry equipment; repair and cleaning of small arms and harness; the manufacture of percussion caps, powder and ammunition, especially the Minié ball; and the testing of new forms of gunpowder and time fuses. During the Gettysburg Campaign, the arsenal provided tens of thousands of muskets and vast supplies of ammunition for Pennsylvania’s Emergency Militia regiments. Among the innovations extensively tested at the arsenal were the Gatling gun, an early form of machine gun, and other innovations in ordnance.210

This depot was originally built as a U.S. Navy powder magazine. The arsenal became an ordnance depot in 1814. Later, the arsenal became a military textile (uniform) depot after 1818. The name of the Schuylkill Arsenal was changed in 1873 to the Philadelphia Depot of the Quartermaster’s Department, United States Army. It was later renamed Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot in 1921. New buildings were built in 1942, and the old complex was later closed. Presently, the site is occupied by the Gray’s Ferry PECO power generating plant, but the surrounding wall and some of the original buildings still stand. The facility evolved into the present-day Defense Supply Center of Philadelphia, serving all branches of the military.211

During the Civil War, more than ten thousand seamstresses and tailors were hired to make uniforms, clothing and equipment for Union troops. Philadelphia troops, for the most part, were equipped with supplies from the two United States arsenals in the city, especially with supplies of uniforms, blankets and various types of equipment manufactured for the Union armies in Philadelphia.212

There were also a number of state, city and individual unit armories located in and around Philadelphia. At the outbreak of the war, there was great excitement in the city, and concern for defense was raised. Therefore, an ordinance for the protection and defense of the city was passed, along with a resolution appropriating public halls for military purposes and a resolution recommending citizens to form companies for the purpose of drilling. The ordinance for the defense and protection of the city was prefaced by a preamble, which declared:

At this unparalleled crisis in our national affairs, it is eminently proper that the city of Philadelphia should be placed in a condition of defense against any attack that might be made. And as arms and other munitions of war may be required here for the proper equipment of the Home Guard that are at our own disposal and can be used, should the occasion arise, for our own defense. Serving also as a means of drill to such companies as might wish to practice, and thus be well prepared at any moment to respond to their country’s call as efficient artillerists.213

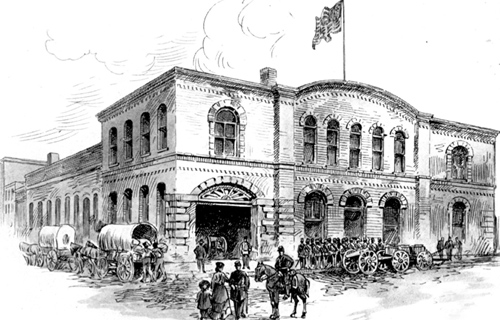

A total of $50,000 was appropriated for the purchase of arms or other munitions of war for the use of a Home Guard or any company that may thereafter be formed for the defense of the city. One week afterward, $200,000 was added to the appropriation. The question of armories for the city military establishment became important. The city was in possession of two large market houses in the neighborhood of Broad and Race Streets. It was determined to put these buildings to military use. By ordinance of November 14, 1861, these premises, one of them at the southwest corner of Juniper and Race Streets and the other on the east side of Broad Street, below Race, were appropriated to the use of the Home Guard, under the direction of the mayor and the Committee of Defense and Protection. A budget of $3,000 was appropriated to pay for the necessary alterations. The building on Race Street was appropriated to arsenal purposes and the storage of cannon. The first piece placed in that building was a cannon with full equipments and ammunition presented to the city by a citizen, James McHenry, then residing in London. A few days afterward, two rifled guns were presented to the city by James Swain, also a native of Philadelphia and residing abroad. They were manufactured in Prussia and, when received, were placed in the Race Street armory.

City Armory at Broad and Race Streets. It was from this armory that many city units were uniformed and equipped for military service. GAR Museum Collection.

Several of the militia units of the city also owned their own armories, which they used for meetings, drill, social gatherings and storage of gear. This included the National Guards, which had purchased in 1857 a lot of ground on the south side of Race Street, between Fifth and Sixth (now the National Constitution Center). A large, three-story brick building was erected, occupying the entire lot and imposing in appearance. This was the National Guards Hall. There were rooms for officers’ regimental headquarters, and reading, writing, drilling, dressing, meeting and storerooms. On the second floor was a large hall with a high ceiling, occupying nearly the whole space from Race Street to Cresson’s Alley. This hall was used for drill and other regimental purposes, inspections and occasionally as a public hall for lectures, fairs, concerts and meetings. It also featured accommodations for troops and, during a portion of the war, was occupied as an army hospital.

The First City Troop also built and owned an armory on the west side of Twenty-first Street at the corner of Ranstead Street. This armory was constructed in 1863. Later, this armory was replaced by the turreted, castle-like structure that stands there now. Frederick Ladner owned a “military hall” in the Northern Liberties neighborhood on Third Street and Brown. Although this building was used as a restaurant and beer hall catering to the German populace of the area and as a concert hall, it also served as an armory and meeting place for militia units, especially the German Rifle Regiment, later to become the 98th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Many other units gathered, enlisted and rendezvoused in hotels and halls all over the city. They used the nearby parks, squares and public grounds to drill for marching and inspections.214

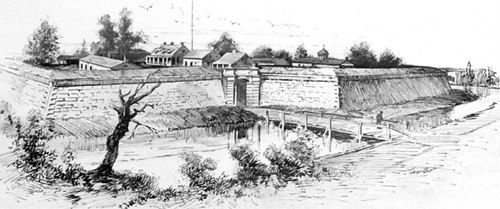

Fort Mifflin next to the Philadelphia Airport was one of the strategic harbor defenses for Philadelphia. During the Civil War, Fort Mifflin held both Union and Confederate prisoners as well as civilian prisoners. The civilian prisoners were held for draft evasion, bounty jumping and treasonous antiwar activities.

A sketch from Taylor’s Philadelphia in the Civil War depicting Fort Mifflin, a Federal fort in Philadelphia near the present airport. GAR Museum Collection.

At its maximum, Fort Mifflin held 215 prisoners, and the overflow was sent to Fort Delaware, farther down the Delaware River on Pea Patch Island opposite Delaware City. A Reverend Dr. Handy was arrested for calling the Union flag an “emblem of oppression.” He had refused to take an oath of allegiance and was imprisoned at Fort Mifflin for fifteen months. A large number of civilians were arrested in the infamous “Fishing Creek Confederacy” campaign in Columbia County, Pennsylvania, in August 1864 and imprisoned at Fort Mifflin in wretched conditions. They were arrested under the provisions of the controversial suspension of the writ of habeas corpus provision of the Lincoln administration. The writ was suspended ostensibly to eliminate resistance to the draft.

There were a number of military executions at Fort Mifflin during the war. The most notorious case was that of the fort’s most famous prisoner, Private William H. Howe of Company A, 116th PV. He was arrested for desertion after he received a severe wound in battle and was sent home to recuperate. But he overstayed his leave, and during his apprehension, a provost guard was murdered. Howe was condemned by court-martial and ordered executed. Howe apparently led an attempted escape of two hundred prisoners from Casemate #5. He was afterward placed in solitary confinement in Casemate #11 in February 1864. Howe was held at Fort Mifflin from January 1864 until April 1864, when he was transferred to Eastern State Penitentiary, a public prison, from which he was returned to Fort Mifflin on the day of his execution, August 26, 1864. He was held in the fort’s wooden guardhouse, just steps from the gallows where he was to be hanged. Howe wrote to President Lincoln twice in his own hand, as well as to the commanding officers of his regiment, seeking clemency for a “brave soldier.” All attempts failed, and Howe was hanged as a murderer and deserter.

Howe was one of four men executed at Fort Mifflin, but he has the distinction of being the only person ever executed by the army for which tickets to the execution were sold to the public. Inside Casemate #11, where Howe was held, his handwritten signature can still be clearly seen on the wall.215