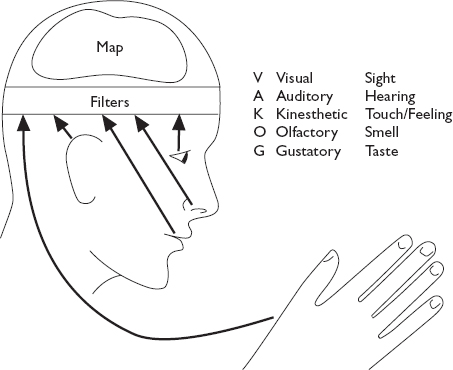

If the loop of communication has any beginning, it starts with our senses. As Aldous Huxley pointed out, the doors of perception are the senses, our eyes, nose, ears, mouth, and skin, and these are our only points of contact with the world.

Even these points of contact are not what they seem. Take your eyes, for example, your “windows on the world”. Well, they are not. Not windows at any rate, nor even a camera. Have you ever wondered why a camera can never catch the essence of the visual image that you see? The eye is much more intelligent than a camera. The individual receptors, the rods and cones of the retina, respond not to the light itself, but to changes or differences in the light.

Consider the apparently simple task of looking at one of these words. If your eye and the paper were perfectly still, the word would disappear as soon as each rod had fired in response to the initial black or white stimulus. In order to keep sending information about the shape of the letters, the eye flickers minutely and rapidly so that the rods at the boundary of black and white keep on being stimulated. In this way we continue to see the letter. The image is projected upside down onto the retina, coded into electrical impulses by the rods and cones and reassembled from these by the visual cortex of the brain. The resulting picture is then projected “out there”, but it is created deep inside the brain.

So we see through a complex series of active perceptual filters. The same is true of our other senses. The world we perceive is not the real world, the territory. It is a map made by our neurology. What we pay attention to in the map is further filtered through our beliefs, interests and preoccupations.

We can learn to allow our senses to serve us better. The ability to notice more, and make finer distinctions in all the senses can significantly enrich the quality of life, and is an essential skill in many work areas. A wine taster needs a very discriminating palate; a musician needs the ability to make fine auditory distinctions. A mason or woodcarver must be sensitive to the feel of his materials to release the figure imprisoned in the stone or wood. A painter must be sensitive to the nuances of color and shape.

Training of this nature is not so much seeing more than others as knowing what to look for, learning to perceive the difference that makes the difference. The development of a rich awareness in each of our physical senses is sensory acuity, and an explicit goal of NLP training.

Communication starts with our thoughts, and we use words, tonality, and body language to convey them to the other person. And what are thoughts? There are many different scientific answers, yet everyone knows intimately what thinking is for themselves. One useful way of thinking about thinking is that we are using our senses internally.

When we think about what we see, hear, and feel, we re-create these sights, sounds, and feelings inwardly. We re-experience information in the sensory form in which we first perceived it. Sometimes we are aware of doing this, sometimes not. Can you remember where you went on your last vacation?

Now, how do you remember it? Maybe pictures of the place come into your mind. Perhaps you say the name or hear sounds. Or maybe you recall what you felt. Thinking is such an obvious, commonplace activity, we never give it a second thought. We tend to think about what we think about, not how we think about it. Also we assume that other people think in the same way as we do.

So one way we think is consciously or unconsciously remembering the sights, sounds, feelings, tastes, and smells we have experienced. Through the medium of language we can even create varieties of sense experience without having had the actual experiences. Read the next paragraph as slowly as you comfortably can.

Take a moment to think about walking in a forest of pine trees. The trees tower above you, rising up on every side. You see the colors of the forest all around you and the sun makes leafy shadows and mosaics on the forest floor. You walk through a patch of sunlight that has broken through the cool ceiling of leaves above you. As you walk, you become aware of the stillness, broken only by the birds calling and the crunching sound of your feet as you tread on the debris of the forest floor. There is the occasional sharp crack as you snap a dried twig underfoot. You reach out and touch a tree trunk, feeling the roughness of the bark under your hand. As you gradually become aware of a gentle breeze stroking your face, you notice the aromatic smell of pine mingling with the more earthy smells of the forest. Wandering on, you remember that supper will be ready soon and it is one of your favorite meals. You can almost taste the food in your mouth in anticipation . . .

To make sense of that last paragraph, you went through those experiences in your mind, using your senses inwardly to represent the experience that was conjured up by the words. You probably created the scene sufficiently strongly to imagine the taste of food in an already imaginary situation. If you have ever walked in a pine forest, you may have remembered specific experiences from that occasion. If you have not, you may have constructed the experience from other similar experiences, or used material from television, films, books, or similar sources. Your experience was a mosaic of memories and imagination. Much of our thinking is typically a mixture of these remembered and constructed sense impressions.

We use the same neurological pathways to represent experience inwardly as we do to experience it directly. The same neurons generate electrochemical charges which can be measured by electromyographic readings. Thought has direct physical effects, mind and body are one system. Take a moment to imagine eating your favorite fruit. The fruit may be imaginary, but the salivation is not.

We use our senses outwardly to perceive the world, and inwardly to “re-present” experience to ourselves. In NLP the ways we take in, store, and code information in our minds—seeing, hearing, feeling, taste, and smell—are known as representational systems.

The visual system, often abbreviated to “V”, can be used externally (e) when we are looking at the outside world (Ve), or internally (i) when we are mentally visualizing (Vi). In the same way, the auditory system (A), can be divided into hearing external sounds (Ae), or internal (Ai). The feeling sense is called the kinesthetic system (K). External kinesthetics (Ke), include tactile sensations like touch, temperature and moisture. Internal kinesthetics (Ki), include remembered sensations, emotions, and the inner feelings of balance and bodily awareness, known as the proprioceptive sense, which provide us with feedback about our movements. Without them we could not control our bodies in space with our eyes closed. The vestibular system is an important part of the kinesthetic system. It deals with our sense of balance, maintaining the equilibrium of our whole body in space. It is located in the complex series of canals in the inner ear. We have many metaphors about this system such as losing our balance, falling for somebody, or being put in a spin. The vestibular system is very influential and is often treated as a separate representational system.

Visual, auditory, and kinesthetic are the primary representation systems used in Western cultures. The sense of taste, gustatory (G), and smell, olfactory (O), are not so important and are often included in the kinesthetic sense. They often serve as powerful and immediate links to the sights, sounds, and pictures associated with them. representational system.

We use all three of the primary systems all the time although we are not equally aware of them all, and we tend to favor some over others. For example, many people have an inner voice that runs in the auditory system creating an internal dialogue. They rehearse arguments, rehear speeches, make up replies, and generally talk things over with themselves. This is, however, only one way of thinking.

Representational Systems

Representational systems are not mutually exclusive. It is possible to visualize a scene, have the associated feelings and hear the sounds simultaneously, although it may be difficult to pay attention to all three at the same time. Some parts of the thought process will be unconscious.

The more a person is absorbed in their inner world of sights, sounds, and feelings, the less he or she will be able to pay attention to the external world. There is a story of a famous chess player in an international tournament who was so engrossed in the position he was seeing in his mind's eye that he had two full dinners in one evening. He had completely forgotten eating the first. Being “lost in thought” is a very apt description. People experiencing strong inner emotions are also less vulnerable to external pain.

Our behavior is generated from a mixture of internal and external sense experience. At any time we will be paying attention to different parts of our experience. While you read this book you will be focusing on the page and probably not aware of the feeling in your left foot . . . until I mentioned it . . .

As I type this, I am mostly aware of my internal dialogue pacing itself to my (very slow) rate of typing on the word processor. I will be distracted if I pay attention to outside sounds. Not being a very good typist, I look at the keys and feel them under my fingers as I type, so my visual and kinesthetic senses are being used outwardly.

This would change if I stopped to visualize a scene I wanted to describe. There are some emergency signals that would get my immediate attention: a sudden pain, my name being called, the smell of smoke, or, if I am hungry, the smell of food.

We use all our senses externally all the time, although we will pay attention to one sense more than another depending on what we are doing. In an art gallery we will use mostly our eyes, in a concert, our ears. What is surprising is that when we think, we tend to favor one, perhaps two representational systems regardless of what we are thinking about. We are able to use them all, and by the age of 11 or 12 we already have clear preferences.

Many people can make clear mental images and think mainly in pictures. Others find this viewpoint difficult. They may talk to themselves a good deal, while others base their actions mostly on their feel for a situation. When a person tends to use one internal sense habitually, this is called their preferred or primary system in NLP; they are likely to be more discriminating and able to make finer distinctions in this system than in the others.

This means some people are naturally better, or “talented” at particular tasks or skills, they have learned to become more adept at using one or two internal senses and these have become smooth and practiced, running without effort or awareness. Sometimes a representational system is not so well developed, and this makes certain skills more difficult. For example, music is a difficult art without the ability to hear sounds internally.

No system is better in an absolute sense than another, it depends what you want to do. Athletes need a well-developed kinesthetic awareness, and it is difficult to be a successful architect without a facility for making clear, constructed mental pictures. One skill shared by outstanding performers in any field is to be able to move easily through all the representational systems and use the most appropriate one for the task in hand.

Different psychotherapies show a representation system bias. The bodywork therapies are primarily kinesthetic; psychoanalysis is predominantly verbal and auditory. Art therapy and Jungian symbolism are examples of more visually based therapies.

We use language to communicate our thoughts so it is not surprising that the words we use reflect the way we think. John Grinder tells of the time when he and Richard Bandler were leaving a house to lead a Gestalt therapy group. Richard was laughing about someone who had said, “I see what you are saying”. “Think about it literally”, he said. “What could they possibly mean?” “Well”, said John, “let's take it literally; suppose it means that people are making images of the meaning of the words that you use”.

This was an interesting idea. When they got to the group, they tried an entirely new procedure on the spur of the moment. They took green, yellow, and red cards and had people go around the group and say their purpose for being there. People who used a lot of words and phrases to do with feelings got a yellow card. People who used a lot of words and phrases to do with hearing and sounds got green cards. Those who used words and phrases predominantly to do with seeing got red cards.

Then there was a very simple exercise. People with the same color card were to sit down and talk together for five minutes. Then they sat down and talked, to somebody with a different color card. The differences they observed in rapport between people were profound. People with the same color card were getting on much better. Grinder and Bandler thought this was fascinating and suggestive.

We use words to describe our thoughts, so our choice of words will indicate which representational system we are using. Consider three people who have just read the same book.

The first might point out that he saw a lot in it, the examples were well chosen to illustrate the subject and it was written in a sparkling style.

The second might object to the tone of the book; it had a shrill prose style. In fact, he cannot tune in to the author's ideas at all, and he would like to tell him so.

The third feels the book dealt with a weighty subject in a balanced way. He liked the way the author touched on all the key topics, and he grasped the new ideas easily. He felt in sympathy with the author.

They all read the same book. You will notice that each person expressed themselves about the same book in a different way. Regardless of what they thought about it, how they thought about it was different. One was thinking in pictures, the second in sounds and the third in feelings. These sensory-based words, adjectives, adverbs, and verbs, are called predicates in NLP literature. Habitual use of one kind of predicate will indicate a person's preferred representational system.

It is possible to find out the preferred system of the writer of any book by paying attention to the language that he or she uses. (Except for NLP books, where the writers may take a rather more calculated approach to the words they use . . .) Great literature always has a rich and varied mix of predicates, using all the representational systems equally, hence its universal appeal.

Words such as “comprehend”, “understand”, “think”, and “process” are not sensory-based, and so are neutral in terms of representational systems. Academic treatises tend to use them in preference to sensory-based words, perhaps as an unconscious recognition that sensorybased words are more personal to the writer and reader and so less “objective”. However, neutral words will be translated differently by the kinesthetic, auditory, or visual readers, and give rise to many academic arguments, often over the meaning of the words. Everyone thinks they are right.

You may like to become aware over the coming weeks what sort of words you favor in normal conversation. It is also fascinating to listen to others and discover what sort of sensory-based language they prefer. Those of you who prefer to think in pictures may like to see if you can identify the colorful language patterns of the people around you. If you think kinesthetically, you could get in touch with the way people put themselves over, and if you think in sounds, we would ask you to listen carefully and tune in to how different people talk.

There are important implications for gaining rapport. The secret of good communication is not so much what you say, but how you say it. To create rapport, match predicates with the other person. You will be speaking their language, and presenting ideas in just the way they think about them. Your ability to do this will depend on two things. Firstly your sensory acuity in noticing, hearing, or picking up other people's language patterns. And secondly, having an adequate vocabulary of words in that representational system to respond. Conversations will not all be in one system of course, but matching language does wonders for rapport.

You are more likely to gain rapport with a person who thinks in the same way as you, and you discover this by listening to the words he or she uses, regardless of whether you agree with them or not. You might be on the same wavelength, or you might see eye to eye. Then again you might get a solid understanding.

It is a good idea to use a good mix of predicates when you address a group of people. Let the visualizers see what you are saying. Let the auditory thinkers hear you loud and clear, and put yourself over so that the kinesthetic thinkers in the audience can grasp your meaning, Otherwise why should they listen to you? You risk two thirds of your audience not following your talk if you confine yourself to explaining in one representational system.

Just as we have a preferred representational system for our conscious thinking, so we also have a preferred means of bringing information into our conscious thoughts. A complete memory would contain all the sights, sounds, feelings, tastes, and smells of the original experience, and we prefer to go to one of these to recall it. Think back again to your vacation.

What came first . . . ?

A picture, sound, or feeling?

This is the lead system, the internal sense that we use as a handle to reach back to a memory. It is how the information reaches conscious mind. For example, I may remember my vacation and start to be conscious of the feelings of relaxation I experienced, but the way it comes to mind initially might be as a picture. Here my lead system is visual and my preferred system is kinesthetic.

The lead system is rather like a computer's start-up program—unobtrusive, but necessary for the computer to work at all. It is sometimes called the input system, as it supplies the material to think about consciously.

Most people have a preferred input system, and it need not be the same as their primary system. A person may have a different lead system for different types of experience. For example, they may use pictures to get in touch with painful experiences, and sounds to take them back to pleasant ones.

Occasionally a person may not be able to bring one of the representational systems into consciousness. For example, a person may say he does not see any mental pictures. While this is true for him in his reality, it is actually impossible, or he would be unable to recognize people, or describe objects. He is simply not conscious of the pictures he is seeing internally. If this unconscious system is generating painful images, he may feel bad without knowing why. This is often how jealousy is generated.

Have you seen but a white lily grow?

Before rude hands have touched it?

Have you marked but the fall of the snow,

Before the soil has smirched it?

Have you felt the wool of beaver,

Or swan's down, ever?

Have you smelt of the bud of the briar

Or the nard in the fire,

Have you tasted the bag of the bee?

O so sweet is she.

Ben Jonson 1572–1637

The richness and range of our thoughts depends on our ability to link and move from one way of thinking to another. So if my lead system is auditory, and my preferred system is visual, I will tend to remember a person through the sound of their voice and then think about them in pictures. From there I might get a feeling for the person.

So we take information in from one sense, but represent it internally with another. Sounds can conjure up visual memories or abstract visual imagery. We talk of tone color in music, and of warm sounds, and also of loud colors. An immediate and unconscious link across the senses is called a synesthesia. A person's lead to preferred system will usually be their strong, typical synesthesia pattern.

Synesthesias form an important part of the way we think and some are so pervasive and widespread that they seem to be wired into our brain at birth. For example, colors are usually linked to moods: red for anger and blue for tranquillity. In fact both blood pressure and pulse rate increase slightly in a predominantly red environment, and decrease if the surroundings are mostly blue. There are studies that show that people experience blue rooms as colder than yellow rooms, even when they are actually slightly warmer. Music makes extensive use of synesthesias; how high a note is set visually on the stave relates to how high it sounds, and there are a number of composers who associate certain musical sounds with definite colors.

Synesthesias happen automatically. Sometimes we want to link internal senses in a purposeful way, for example, to gain access to a whole representation system that is out of conscious awareness.

Suppose a person has great difficulty visualizing. First you could ask her to go back to a happy, comfortable memory, perhaps a time by the sea. Invite her to hear the sound of the sea internally, and the sound of any conversation that took place. Holding this in mind, she might overlap to feeling the wind on her face, the warmth of the sun on her skin, and the sand between her toes. From here it is a short step for her to see an image of the sand beneath her feet, or see the sun in the sky. This technique of overlapping can bring back a full memory: pictures, sounds and feelings.

Just as a translation from one language to another preserves the meaning but totally changes the form, so experiences can be translated between internal senses. For example, you might see a very untidy room, get an uncomfortable feeling and want to do something about it. The sight of the same room might leave a friend feeling unaffected and he would be at a loss to understand why you feel so bad. He might label you as oversensitive because he cannot enter into your world of experience. He might understand how you feel if you told him it was like having itching powder in his bed. Translating into sound, you might compare it to the discomfort of hearing an instrument played out of tune. This analogy would strike a chord with any musician; you would at last be speaking his language.

It is easy to know if a person is thinking in pictures, sounds or feelings. There are visible changes in our bodies when we think in different ways. The way we think affects our bodies, and how we use our bodies affects the way we think.

What is the first thing you see as you walk through the front door of your home?

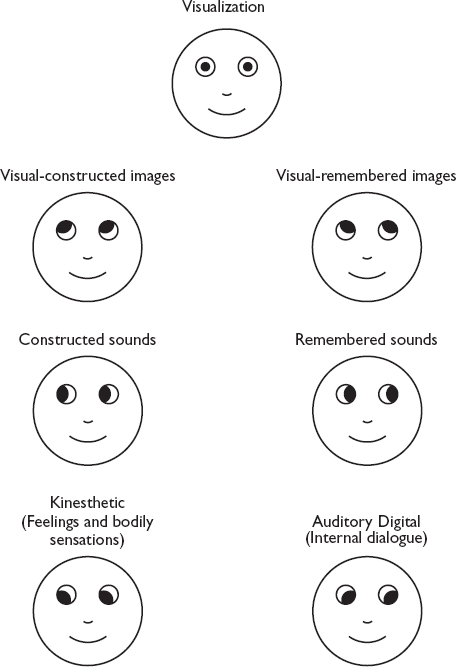

To answer that question you probably looked up and to your left. Looking up and left is how most right-handed people remember images.

Now, really get in touch with how it would feel to have velvet next to your skin.

Here you probably looked down and to your right, which is the way the majority of people get in touch with their feelings.

We move our eyes in different directions in a systematic way depending on how we are thinking. Neurological studies have shown that eye movement both laterally and vertically seems to be associated with activating different parts of the brain. These movements are called lateral eye movements (LEM) in neurological literature. In NLP they are called eye accessing cues because they are the visual cues that let us know how people are accessing information. There is some innate neurological connection between eye movements and representational systems, for the same patterns occur worldwide (with the exception of the Basque region of Spain).

When we visualize something from our past experience our eyes tend to move up and to our left. When constructing a picture from words or trying to “imagine” something we have never seen, our eyes move up and to our right. The eyes move across to our left for remembered sounds and across to our right for constructed sounds. When accessing feelings, the eyes will typically go down to our right. When talking to ourselves, the eyes will usually go down left. Defocusing the eyes and staring straight ahead, “looking into the distance”, also shows visualization.

NB: This is as you look at another person

Most right-handed people have the pattern of eye movements shown in the diagram. They may be reversed for left-handed people, who may look right for remembered images and sounds, and left for constructed images and sounds. Eye accessing cues are consistent for a person even if they contradict this model. For example, a left-handed person may look down to his left for feelings and down to his right for internal dialogue. However, he will do this consistently and not mix the accessing cues randomly. There are always exceptions—look carefully before applying these general rules to anybody. The answer is not the generalization, but the person in front of you.

Although it is possible to move your eyes consciously in any direction while thinking, accessing a particular representation system is generally much easier if you are using the appropriate natural eye movements. They are ways of fine tuning the brain to think in a particular way. If you want to remember something you saw yesterday, it is easiest to look up to your left or stare straight ahead. It is difficult to remember images while looking down.

We are not normally conscious of our lateral eye movements and there is no reason why we should be, but “looking” for information in the right place is a very useful skill.

Accessing cues allow us to know how another person is thinking, and an important part of NLP training involves becoming aware of other people's eye accessing cues. One way to do this is to ask different sorts of questions and notice the eye movements, not the replies. For example, if I ask, “What color is your lounge carpet?” you would have to visualize the lounge to give the answer regardless of the color.

You might like to try out the following exercise with a friend. Sit down in a quiet place, ask her the following questions and watch her eye accessing cues. Make a note of them if you want to. Tell her to keep her answers brief or just nod when she has the answer. When you have finished, change places, and answer the questions yourself.

This is nothing to do with trying to catch her out to prove a point, only simple curiosity about how we think.

What color is your front door?

What do you see on your journey to the nearest shop?

How do the stripes go around a tiger's body?

How tall is the building you live in?

Which of your friends has the longest hair?

What would your bedroom look like with pink-spotted wallpaper?

If a map is upside down, which direction is southeast?

Imagine a purple triangle inside a red square.

How do you spell your Christian name backward?

Can you hear your favorite piece of music in your mind?

Which door slams loudest in your house?

What is the sound of the engaged tone on the telephone?

Is the third note in the national anthem higher or lower than the second note?

Can you hear the dawn chorus in your mind?

How loud would it be if ten people shouted at once?

What would your voice sound like underwater?

Think of your favorite tune played at double speed.

What sound would a piano make if it fell off the top of a tenstorey building?

What would the scream of a mandrake sound like?

What would a chainsaw sound like in a corrugated iron shed?

What tone of voice do you use when you talk to yourself? Recite a nursery rhyme silently.

When you talk to yourself, where does the sound come from?

What do you say to yourself when things go wrong?

What does it feel like to put on wet socks?

What is it like to put your foot into a cold swimming pool?

What is it like to feel wool next to the skin?

Which is warmer now, your left hand or your right hand?

What is it like to settle down in a nice hot bath?

How do you feel after a good meal?

Think of the smell of ammonia.

What is it like to taste a spoonful of very salty soup?

The thought process is what matters, not the actual answers. It is not even necessary to get verbal replies. Some questions can be thought of in different ways. For example, to find out the number of sides of a 50 pence piece, you might visualize the coin and count the sides, or alternatively, you might count them by mentally feeling around the edge. So if you ask a question that should evoke visualization, and the accessing cues are different, this is a tribute to the person's flexibility and creativity. It does not mean that the patterns are wrong necessarily, or the person is “wrong”. If in doubt, ask, “What were you thinking then?”

Eye accessing cues happen very quickly, and you need to be observant to see them all. They will show the sequence of representational systems that a person uses to answer these questions. For example, in the auditory question about the loudest slamming door, a person might visualize each door, mentally feel himself slamming it and then hear the sound. He might have to do this several times before being able to give an answer. Usually a person will go to their lead system first to answer a question. Someone who leads visually will typically make a picture of the various situations in the auditory and feeling questions before hearing the sound or having the feeling.

Eye movements are not the only accessing cues, although they are probably the easiest to notice. As the body and mind are inseparable, how we think always shows somewhere, if you know where to look. In particular, it shows in breathing patterns, skin color, and posture.

A person who is thinking in visual images will generally speak more quickly and at a higher pitch than someone who is not. Images happen fast in the brain and you have to speak fast to keep up with them. Breathing will be higher in the chest and more shallow. There is often an increase in muscle tension, particularly in the shoulders, the head will be up, and the face will be paler than it is normally.

People who are thinking in sounds breathe evenly over the whole chest area. There are often small rhythmic movements of the body and the voice tonality is clear, expressive, and resonant. The head is well balanced on the shoulders or slightly at an angle as if listening to something.

People who are talking to themselves will often lean their head to one side, resting it on their hand or fist. This is known as a “telephone position” because it looks as if they are speaking on an invisible telephone. Some people repeat what they have just heard under their breath. You will be able to see their lips move.

Kinesthetic accessing is characterized by deep breathing low in the stomach area, often accompanied by muscle relaxation. With the head down, the voice will have a deeper tonality, and the person will typically speak slowly, with long pauses. Rodin's famous sculpture of “The Thinker” is undoubtedly thinking kinesthetically.

Movements and gestures will also tell you how a person is thinking. Many people will point to the sense organ that they are using internally: they will point to their ears while listening to sounds inside their head, point to the eyes if visualizing, or to the abdomen if they are feeling something strongly. These signs will not tell you what a person is thinking about, only how he or she is thinking it. This is body language at a much more refined and subtle level than it is normally interpreted.

The idea of representational systems is a very useful way of understanding how different people think, and reading accessing cues is an invaluable skill for anyone who wants to communicate better with others. For therapists and educators it is essential. Therapists can begin to know how their clients are thinking, and discover how they might change it. Educators can discover what ways of thinking work best for a particular subject and teach those precise skills.

There have been many theories of psychological types based both on physiology and ways of thinking. NLP suggests another possibility. Habitual ways of thinking leave their mark on the body. These characteristic postures, gestures and breathing patterns will become habitual in individuals who think predominantly in one way. In other words, a person who speaks quickly in a high tonality, who breathes fairly rapidly high in the chest, and who is tense in the shoulder area is likely to be someone who thinks mostly in pictures. A person who speaks slowly, with a deep voice, breathing deeply as he or she does so, will probably rely on their feelings to a large extent.

A conversation between a person thinking visually and a person thinking in feelings can be a very frustrating experience for both sides. The visual thinker will be tapping his foot in impatience, while the kinesthetic person literally “can't see” why the other has to go so quickly. Whoever has the ability to adapt to the other person's way of thinking will get better results.

However, do remember that these generalizations must all be checked against observation and experience. NLP is emphatically not another way to pigeonhole people into types. To say that someone is a visual type is no more useful than saying he has red hair. If it blinds you to what he is doing in the here and now, it is worse than useless, and just another way of creating stereotypes.

There can be a great temptation to categorize yourself and others in terms of primary representation system. To make this error is to fall into the trap that has beset psychology: invent a set of categories and then cram people into them whether they fit or not. People are always richer than generalizations about them. NLP provides a rich enough set of models to fit what people actually do rather than try to make the people fit the stereotypes.

So far we have talked about three main ways of thinking—in sounds, in pictures and in feelings—but this is only a first step. If you wanted to describe a picture you have seen, there is a lot of detail you could add. Was it in color or black and white? Was it a moving-film strip, or still? Was it far away or near? These sorts of distinctions can be made regardless of what is in the picture. Similarly you could describe a sound as high or low pitched, near or far, loud or soft. A feeling could be heavy or light, sharp or dull, light or intense. So having established the general way we think, the next step is to be much more precise within that system.

Make yourself comfortable and think back to a pleasant memory. Examine any picture you have of it. Are you seeing it as if through your own eyes (associated), or are you seeing it as if from somewhere else (dissociated)? For example, if you see yourself in the picture, you must be dissociated. Is it in color? Is it a movie or a slide? Is it a three-dimensional image or is it flat like a photograph? As you continue to look at the picture you may make other descriptions of it as well.

Next pay attention to any sounds that are associated with that memory. Are they loud or soft? Near or far? Where do they come from?

Finally pay attention to any feelings or sensations that are a part of that memory. Where do you feel them? Are they hard or soft? Light or heavy? Hot or cold?

These distinctions are known as submodalities in NLP literature. If representational systems are modalities—ways of experiencing the world—then submodalities are the building blocks of the senses, how each, picture, sound or feeling is composed.

People have used NLP ideas throughout the ages. NLP did not spring into being when the name was invented. The ancient Greeks talked about sense experience, and Aristotle talked about submodalities in all but name when he referred to the qualities of the senses.

Here is a list of the most common submodality distinctions:

Associated (seen through own eyes), or dissociated (looking on at self)

Color or black and white

Framed or unbounded

Depth (two or three dimensional)

Location (e.g. to left or right, up or down)

Distance of self from picture

Brightness

Contrast

Clarity (blurred or focused)

Movement (like a film or a slide show)

Speed (faster or slower than usual)

Number (split screen or multiple images)

Size

Stereo or mono

Words or sounds

Volume (loud or soft)

Tone (soft or harsh)

Timbre (fullness of sound)

Location of sound

Distance from sound source

Duration

Continuous or discontinuous

Speed (faster or slower than usual)

Clarity (clear or muffled)

Location

Intensity

Extent (how big)

Texture (rough or smooth)

Weight (light or heavy)

Temperature

Duration (how long it lasts)

Shape

These are some of the most common submodality distinctions that people make, not an exhaustive list. Some submodalities are discontinous or digital; like a light switch, on or off, an experience has to be one or the other. An example would be associated or dissociated; a picture cannot be both at the same time. Most submodalities vary continuously, as if controlled by a dimmer switch. They form a sort of sliding scale, e.g. clarity, brightness, or volume. Analogue is the word used to describe these qualities that can vary continuously between limits.

Many of these submodalities are enshrined in the phrases we use, and if you look to the list at the end of this chapter, you may see them in a new light or they may strike you differently, for they speak volumes about the ways our minds work. Submodalities can be thought of as the most fundamental operating code of the human brain. It is simply not possible to think any thought or recall any experience without it having a submodality structure. It is easy to be unaware of the submodality structure of experience until you put your conscious attention on it.

The most interesting aspect of submodalities is what happens when you change them. Some may be changed with impunity and make no difference. Others may be crucial to a particular memory, and changing them changes the whole way we feel about the experience. Typically the impact and meaning of a memory or thought is more a function of a few critical submodalities than it is of the content.

Once an event has happened, it is finished and we can never go back and change it. After that, we are not responding to the event any more, but to our memory of the event, which can be changed.

Try this experiment. Go back to your pleasant experience. Make sure you are associated in the picture, seeing it as through your own eyes. Experience what this is like. Next dissociate. Step outside it and view the person who looks and sounds very like you. This will almost certainly change how you feel about the experience. Dissociating from a memory robs it of its emotional force. A pleasant memory will lose its pleasure, an unpleasant one, its pain. When dealing with trauma, it is important to dissociate from the emotional pain first, otherwise the whole episode may be completely blocked out of consciousness and be difficult if not impossible to think about. Dissociating first puts the feelings at a safe distance so they can be dealt with. This is the basis of the phobia cure set out in Chapter 8. The next time your brain conjures up a painful scene, dissociate from it. To enjoy pleasant memories to the full, make sure you are associated. You can change the way you think. This is one essential piece of information for the unwritten Brain Users' Manual.

Try this experiment in changing how you think and discover which submodalities are most critical for you.

Think back to a specific situation of emotional significance that you can remember well. First become aware of the visual part of the memory. Imagine yourself turning the brightness control up and down, just as you would on a TV. Notice what difference it makes to your experience when you do this. What brightness do you prefer? Finally put it back how it was originally.

Next bring the image closer, then push it far away. What difference does this make and which do you prefer? Put it back how it was.

Now, if it has color, make it black and white. If it was black and white give it color. What is the difference and which is better? Put it back.

Next, does it have movement? If so, slow it right down until it is at a standstill. Then try speeding it up. Notice your preference and put it back.

Finally try changing from associated to dissociated and back.

Some or all of these changes will have a profound impact on how you feel about that memory. You may like to leave the memory with the submodalities at the values you like best. You may not like the default values your brain has given you. Do you remember choosing them?

Now, carry on your experiment with the other visual submodalities and observe what happens. Do the same for the auditory and kinesthetic parts of the memory.

For most people an experience will be most intense and memorable if it is big, bright, colorful, close, and associated. If this is so for you, then make sure you store your good memories like this. By contrast, make your unpleasant memories small, dark, black and white, far away and dissociate from them. In both cases the content of the memory stays the same; it is how we remember it that has changed. Bad things happen and have consequences that we have to live with, but they need not haunt us. Their power to make us feel bad in the here and now is derived from the way we think about them. The crucial distinction to make is between the actual event at the time, and the meaning and power we give it by the way we remember it.

Perhaps you have an internal voice that nags you.

Slow it down.

Now speed it up.

Experiment with changing the tone.

Which side does it come from?

What happens when you change it to the other side?

What happens if you make it louder?

Or softer?

Talking to yourself can be made a real pleasure.

The voice may not even be your own. If it is not, ask it what is it doing inside your head.

Changing submodalities is a matter of personal experience, difficult to convey in words. Theory is arguable, experience is convincing. You can be the director of your own mental film show and decide how you want to think, rather than be at the mercy of the representations that seem to arise of their own accord. Like television in summer, the brain shows a lot of repeats, many of which are old, and not very good films. You do not have to watch them.

Emotions come from somewhere, although their cause may be out of conscious awareness. Also, emotions themselves are a kinesthetic representation and have weight, location and intensity; they have submodalities which can be changed. Feelings are not entirely involuntary and you can go a long way toward choosing the feelings you want. Emotions make excellent servants, but tyrannical masters.

Representational systems, accessing cues, and submodalities are some of the essential building blocks of the structure of our subjective experience. It is no wonder that people make different maps of the world. They will have different lead and preferred representational systems, different synesthesias, and code their memories with different submodalities. When finally we use language to communicate, it is a wonder we understand each other as well as we do.

Look, picture, focus, imagination, insight, scene, blank, visualize, perspective, shine, reflect, clarify, examine, eye, focus, foresee, illusion, illustrate, notice, outlook, reveal, preview, see, show, survey, vision, watch, reveal, hazy, dark.

Say, accent, rhythm, loud, tone, resonate, sound, monotonous, deaf, ring, ask, accent, audible, clear, discuss, proclaim, remark, listen, ring, shout, speechless, vocal, tell, silence, dissonant, harmonious, shrill, quiet, dumb.

Touch, handle, contact, push, rub, solid, warm, cold, rough, tackle, push, pressure, sensitive, stress, tangible, tension, touch, concrete, gentle, grasp, hold, scrape, solid, suffer, heavy, smooth.

Decide, think, remember, know, meditate, recognize, attend, understand, evaluate, process, decide, learn, motivate, change, conscious, consider.

Scented, stale, fishy, nosy, fragrant, smoky, fresh.

Sour, flavour, bitter, taste, salty, juicy, sweet.

I see what you mean.

I am looking closely at the idea.

We see eye to eye.

I have a hazy notion.

He has a blind spot.

Show me what you mean.

You'll look back on this and laugh.

This will shed some light on the matter.

It colors his view of life.

It appears to me.

Taking a dim view.

The future looks bright.

The solution flashed before his eyes.

Mind's eye.

Sight for sore eyes.

On the same wavelength.

Living in harmony.

That's all Greek to me.

A lot of mumbo jumbo.

Turn a deaf ear.

Rings a bell.

Calling the tune.

Music to my ears.

Word for word.

Unheard-of.

Clearly expressed.

Give an audience.

Hold your tongue.

In a manner of speaking.

Loud and clear.

I will get in touch with you.

I can grasp that idea.

Hold on a second.

I feel it in my bones.

A warm-hearted man.

A cool customer.

Thick skinned.

Scratch the surface.

I can't put my finger on it.

Going to pieces.

Control youself.

Firm foundation.

Heated argument.

Not following the discussion.

Smooth operator.

A fishy situation.

A bitter pill.

Fresh as a daisy.

A taste for the good life.

A sweet person.

An acid comment.