As human beings, we are all naturally gifted learners. For many of us, this process slows down as we grow older. For some, learning continues unabated for a lifetime. When we are growing up, we teach ourselves to walk and talk by being with people who do these things. On a daily basis, we take actions (our first tentative steps), notice our results (falling over repeatedly), and change our actions accordingly (leaning on chairs and people). In essence, this is learning by modeling. As we grow older, we tend to reinterpret this natural learning process as a series of tiny “successes” and “failures”. With reinforcement from parents and peers, we begin to long for the “successes” and fear the “failures”. It seems that this fear of “doing it wrong”, more than anything else, is how we learn to inhibit our natural learning processes. Mark Twain once said that if people learned to walk and talk the way they were taught to read and write, everyone would limp and stutter.

So what are some of the differences between the way we learn naturally and the ways that do not work so well? It may be useful at this point to compare this natural learning process with John and Richard's first exploration of modeling.

When John and Richard met and became friends at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1972, John was an Assistant Professor of Linguistics and Richard was in his final year at the college. Richard had a strong interest in Gestalt therapy. He had clone a study and made some video tapes of Fritz Perls at work for his friend Bob Spitzer, who owned the publishers Science and Behavior Books. These tapes later went to make up a book called Eyewitness To Therapy.

Bob Spitzer owned property near Santa Cruz, and used to let it out to his friends. Gregory Bateson was living there at the time, and Richard moved into a house on the same property, a stone's throw from Bateson. Richard started leading weekly Gestalt encounter groups, charging participants $5.00 a night. He re-established contact with John Grinder and got him interested enough in Gestalt to come to these groups.

When John came, he was intrigued. Richard knew he could successfully run Gestalt groups, but he wanted to know exactly how he did it, and which patterns were effective. There is a big difference between having a skill and knowing explicitly how you succeed with it. John and Richard made a deal. Richard would show John how he did Gestalt therapy, and John would teach Richard what it was that he was doing. So John would go to the Monday night group and model Richard, Richard would indicate what he believed were the important patterns by pointing with his eyes and using different voice intonations.

John learned very quickly. It took him two months to unpack the patterns and be able to perform like Richard. He used to do what they called a “repeat miracle” group on Thursday night. People got the same miracles in their lives on Thursday night from John that others had already had on Monday night from Richard.

Richard then got a job observing and videotaping a month-long training program that Virginia Satir was holding in Canada for family therapists. Richard had met Virginia before and they were already on friendly terms. Throughout the program, he was isolated in his own little recording room except for the microphones to the seminar room. He had a split earphone and would monitor recording levels through one ear and play tapes of Pink Floyd through the other. In the last week Virginia had set up a counseling situation and asked how the participants would deal with it, using the material that she had been teaching them. The participants seemed stuck. Richard came storming down from his room and successfully dealt with the problem. And Virginia said, “That's exactly right”. Richard found himself in the strange situation of knowing more about Virginia's therapeutic patterns than anyone else, without consciously trying to learn them at all. John modelled some of Virginia Satir's patterns from Richard and made them explicit. Their efficiency was improving. This time they did it in three weeks, instead of two months.

Now they had a double description of effective therapy, two complementary and contrasting models: Virginia Satir and Fritz Perls. The fact that they were totally different characters and would not have been able to coexist amicably in the same room made them especially valuable examples. The therapeutic patterns they had in common were much clearer because their personal styles were so different.

They continued and modelled Milton Erickson next, adding a rich collection of hypnotic patterns. The process of modeling out the skills of outstanding performers in business, education, health care, etc., is unusually productive and has grown rapidly in range and sophistication since the early days.

So modeling is at the heart of NLP. NLP is the study of excellence, and modeling is the process that makes explicit the behavioral patterns of excellence. What are the behavioral patterns of successful people? How do they achieve their results? What do they do that is different from people who are not successful? What is the difference that makes the difference? The answers to these questions have generated all the skills, techniques, and presuppositions associated with NLP.

Modeling can be simply defined as the process of replicating human excellence. Explanations of why some people excel more than others usually cite inborn talent. NLP by-passes this explanation by exploring how we can excel as quickly as possible. By using our mind and body in the same way as a peak performer, we can immediately increase the quality of our actions and our results. NLP models what is possible, because real human beings have actually done it.

There are three phases in the full modeling process. The first phase involves being with your model while he is doing the behavior that you are interested in. During this first phase, you imagine yourself in his reality, using second position skills, and do what he does until you can create roughly the same results. You focus on what he does (behavior and physiology), how he does it (internal thinking strategies) and why he does it (the supporting beliefs and assumptions). The what you can get from direct observation. The how and why you explore by asking questions.

In the second phase you systematically take out elements of the model's behavior to see what makes a difference. If you leave something out, and it makes little difference, then it is not necessary.

If you leave something out and it does make a difference to the results you get, then it is an essential part of the model. You refine the model and begin to understand it consciously during this phase.

This is the exact opposite of traditional learning patterns. Traditional learning says add pieces a bit at a time, until you have them all. However, this way you cannot easily know what is essential. Modeling, which is the basis of accelerated learning, gets all the elements, and then subtracts to find what is needed.

The third and final phase is designing a way to teach the skill to others. A good teacher will be able to create an environment, so her students learn for themselves how to get the results.

Models are designed to be simple and testable. You do not need to know why they work, just as you do not need to understand why or how cars work to drive one. If you are lost in the maze of human behavior, you need a map to find your way around, not a psychological analysis of why you want to find your way out of the labyrinth in the first place.

Modeling in any field gives results and techniques, and also further tools for modeling. NLP is generative because its results can be applied to make it even more effective. NLP is a “bootstrap program” for personal development. You can model your own creative and resourceful states and so be able to enter them at will. And with more resources and creativity at your disposal you can become yet more resourceful and creative . . .

If you model successfully, you will get the same results as your model, and you do not have to model excellence. To find out how a person is creative, or how he manages to become depressed, you ask the same key questions. “If I had to stand in for you for a day, what would I have to do to think and behave like you?”

Each person brings his own unique resources and personality to what he does. You cannot become another Einstein, Beethoven, or Edison. To achieve and think exactly like them you would need their unique physiology and personal history. NLP does not claim anyone can be an Einstein, however it does say that anyone can think like an Einstein, and apply those ways of thinking, should he choose, in his life; in doing this, he will come closer to the full flower of his own personal genius, and his own unique expression of excellence.

In summary, you can model any human behavior if you can master the beliefs, the physiology and the specific thought processes, that is, the strategies, that lie behind it. Before going on to explore these in more detail, it is worth remembering that we are only touching the surface of a domain as vast as our own future potential.

The beliefs that we each have about ourselves, others and the way the world is have a major impact on the quality of our experience. Because of the “self-fulfilling prophecy effect”, beliefs influence behavior. They can support particular behavior or inhibit it. This is why modeling beliefs is so important.

One of the simplest ways to model the beliefs of people with outstanding abilities is to ask them questions about why they do what they do. The answers they give you will be rich with insights into their beliefs and values. There is a story of a child in Rome who spent hours watching a strange young man working intently. Finally, the boy spoke. “Signore, why are you hitting that rock?” Michelangelo looked up from his work and answered, “Because there's an angel inside and it wants to come out”.

Beliefs will generally take one of three main forms. They can be beliefs about what things mean. For example, if you believe that life is basically a competitive struggle and then you die, you are likely to have a very different experience of life than if you believe that it is a kind of spiritual school with many rich and fulfilling lessons on offer.

Beliefs can also be about what causes what (cause and effect) and so give rise to the rules we choose to live by. Or again they can be beliefs about what is important and what matters most, so giving rise to our values and criteria.

In modeling out beliefs, you want to focus on those that are most relevant to and supportive of the particular skills and competencies that you are interested in. Some good questions to elicit beliefs and metaphors are:

Once you have elicited the beliefs of your model, you can begin to experiment with them for yourself. When you go beyond simple understanding and actually “try on a belief” to “see how it fits”, the difference can be profound. You do this by simply acting for a time as if the belief were true and noticing what changes when you do. One of Einstein's core beliefs was that the universe is a friendly place. Imagine how different the world might seem if you were to act as if that were true.

What new actions would you take if you believed that?

What would you do differently?

What else would you be capable of?

If you realize that the only thing between you and what you want is a belief, you can begin to adopt a new one by simply acting as if it were true.

Imagine for a moment that you are looking at a very small baby. As the baby looks up at you, eyes open wide, you flash it an enormous smile. The baby coos in delight and smiles right back at you. By matching your physiology, in this instance your smile, the baby experiences a bit of your delight in watching it. This is a phenomenon known as entrainment—where babies unconsciously begin to mimic exactly the expressions, patterns, and movements of the people around them. As adults, taking on the expressions, tonalities, and movements of the people around us can enable us to replicate their inner state, which will allow us access to previously untapped emotional resources. Take a moment now to think of someone you admire or respect. Imagine how he would be sitting if he were reading this book. How would he be breathing? What kind of expression would he have on his face? Now actually shift your body until you are sitting and breathing in the same way with the same expression. Notice the new thoughts and feelings that arise as you do this.

With some skills, replicating physiology may be the most important part. To model an excellent skier, for example, you would watch him ski until you begin to move your body in the same way. This will give you an experience of what it is like to do what he does, and you may even have some intuitions about what it is like to be that person, or at least to be inside that body. By precisely mirroring the patterns of movement, posture, and even breathing, you will begin to feel the same way as him on the inside. You will have gained access to resources that may have taken him years to discover.

Thinking strategies are perhaps the least obvious component of modeling. For that we reason, we will look at strategies in depth before moving on to look at other aspects of modeling.

Strategies are how you organize your thoughts and behavior to accomplish a task. Strategies always aim for a positive goal. They can be switched on or off by beliefs; to succeed in a task, you need to believe you can do it, otherwise you will not commit yourself fully.

You must also believe you deserve to do it, and be prepared to put in the necessary practice or preparation. Also, you must believe it is worth doing. The task must engage your interest or curiosity.

The strategies we use are part of our perceptual filters; they determine how we perceive the world. There is a little game that eloquently makes this point. Read the following sentence and count how many times you see the letter “F”.

FINISHED FILES ARE THE RESULT OF YEARS OF SCIENTIFIC STUDY COMBINED WITH THE EXPERIENCE OF MANY YEARS.

Easy? The interesting thing is that different people see different numbers of “F”s and they are all sure they are right. And so they are, each in their own reality. Most people get three “F”s on their first pass, but a few see more. Remember, if what you are doing is not working, do something different. In fact do something very different. Go through the sentence backward letter by letter. How many “F”s were you conscious of at first and how many were you unconscious of?

The reason you missed some of them was probably because you said the words to yourself and were relying on the sound of the “F”s to alert you to their presence. “F” sounds like “V” in the word “of “. As soon as you look at every word backward so that the letters do not link together to make a familiar word, the “F”s are easily seen. We asked how many times you see the letter “F”, not how many times you hear it. The world seems different when you change strategies.

To understand strategies think of a master chef. If you use his recipe, you will probably be able to cook as well as he does, or very close. A strategy is a successful recipe. To make a wonderfully tasty dish, you need to know three basic things. You need to know what the ingredients are. You need to know how much of each ingredient to use, and the quality of each ingredient. And you need to know the correct order of steps. It makes a big difference to the cake whether you add the eggs before, during, or after you put it in the oven to bake. The order in which you do things in a strategy is just as crucial, even if it all happens in a couple of seconds. The ingredients of a strategy are the representational systems, and the amounts and quality are the submodalities. To model a strategy you need:

Suppose you have a friend who is very skilled in some field. It could be interior design, buying clothes, teaching math, getting up in the morning, or being the life and soul of the party. Have your friend either do that behavior, or think back to a specific time when he was doing it. Make sure you have rapport and he is in an associated congruent state.

Ask, “What was the very first thing you did, or thought, in this situation?” It will be something they saw (V), heard (A), or felt (K).

When you have this, ask, “What was the very next thing that happened?” Continue until you have gone all the way through the experience.

Your questions and observations, perhaps using the Meta Model, will find out what representation systems the person is using and in what order. Then ask about the submodalities of all the VAK representations you discovered. You will find accessing cues and predicates very helpful in directing your questions. For example, if you ask, “What comes next?” and the person says, “I don't know”, and looks up, you might ask if they are seeing any mental picture as the next step for them could be visual internal. If you ask and the person replies, “I don't know, it just seems clear to me”, you again would ask about internal pictures.

In the strategy the senses may be turned toward the outside world, or be used internally. If they are being used internally, you will be able to discover if they are being used to remember or construct by watching the eye accessing cues.

For example, someone may have a motivation strategy that starts by looking at the work he has to do (visual external) (Ve). He then constructs an internal picture of the work finished (visual internal constructed) (Vie), gets a good feeling (kinesthetic internal) (Ki) and tells himself he had better get started (auditory dialogue) (Aid). If you wanted to motivate this person you would say something like, “Look at this work, think how good you'll feel when it's finished, here, (hear, phonological ambiguity), you'd better get started”.

Total strategy Vc > Vic > Ki > Aid

You would need a quite different approach for someone who looks at the work (Ve), and asks himself (Aid), “What would happen if I did not complete this?” He constructs possible consequences (Vie), and feels bad (Ki). He does not want this feeling and those consequences, so he starts. The first person is going for the good feeling. The second person is avoiding the bad feeling. You could motivate the first person by giving him tempting futures and the second by threatening reprisals.

Teachers, managers, trainers all need to motivate people, so knowing these strategies is very useful. Everyone has a buying strategy, and good salespeople will not give everybody the same set talk. Some people need to see a product, talk it over with themselves until they get the feeling they want it. Others may need to hear about it, feel it is a good idea, and see themselves using it before buying. Good salesmen change their approach accordingly if they really want to satisfy their customers.

It is essential for teachers to understand and respond to different children's learning strategies. Some children may need to listen to the teacher and then make internal pictures to understand a idea. Others may need some visual representation first. A picture may be worth a thousand words, but a lot depends on who is looking at it. Some students would rather have a thousand words any day. A teacher who insists that there is only one right way of learning is liable to be insisting that everyone ought to use his strategy. This makes it hard for many of his students who do not share it.

Insomniaes could learn a strategy for going to sleep. They could start by attending to the relaxed bodily sensations (Kl) while telling themselves in a slow, drowsy voice (AId) how comfortable they are. Their existing strategy may involve paying attention to all the uncomfortable sensations in their body, while listening to a loud, anxious internal voice telling them how difficult it is to go to sleep. Add some fast moving, bright, and colorful pictures and they have an excellent strategy for staying awake, quite the opposite of what they want.

Strategies create results. Are they the results you want? Do you arrive where you want to go? Any strategy, like a train, works perfectly well, but if you get on the wrong one . . . you will go somewhere you do not want to go. Don't blame the train.

A good example of some of these ideas comes from a study carried out by one of the authors on the way talented musicians memorize music; how they are able to retain sequences of music after only one or two hearings. The students were asked to clap or sing back short pieces of music, and their strategy was elicited by asking questions, watching accessing cues, and noticing predicates.

The most successful students shared several patterns. They consistently adopted a particular posture, eye position, and breathing pattern, usually with the head tilted to one side and the eyes looking downwards while listening. They tuned their bodies to the music.

As they listened (Ae), they got an overall feeling for the music (Ki). This was often described as the “mood” or “imprint” of the piece. This feeling represented the piece as a whole, and their relationship to it.

The next step was to form some visual representation of the music. Most students visualized some sort of graph with the vertical axis representing the rise and fall of pitch, and the horizontal axis used to represent duration in time (V1c).

The longer or more difficult the piece, the more the students relied on this image to guide them through. The image was always bright, clear, focused, and at a comfortable distance to read. Some students visualized a stave with the exact note values just like a score, but this was not essential.

The feeling, sound, and picture were built up together on the first listening. The feeling gave an overall context for the detailed image. Subsequent hearings were used to fix parts of the tune that were still uncertain. The harder the tune, the more important these feeling and visual memories were. The students reheard the tune mentally immediately after it had finished, in its original tonality, and usually at a much faster speed, rather like the fast forward mode on a video recorder (Aic).

All students reheard the tune, usually in its original tonality (Alr), while singing or clapping it back. They also reviewed the picture, and kept the overall feeling in mind. This gave them three ways of storing and retrieving the piece. They broke the music down into smaller sections, and noticed repetitive patterns in both pitch and rhythm. These were remembered visually, even after one hearing.

Remembering music seems to involve a strong auditory memory, but this study showed it is a synesthesia. It is hearing the picture of the feeling of the tune. They heard the tune, created a feeling to represent the piece as a whole, and used what they heard and felt to form a picture of the music.

The basic strategy is Ae > Ki > Vic > Ai. This strategy illustrates some general points about effective memorization and learning. The more representations you have of the material the more you are likely to remember it. The more of your neurology you commit, the stronger the memory. The best students also had the ability to move between representational systems, sometimes concentrating on the feeling, sometimes on the picture, depending on the sort of music they heard. All the students believed in their ability. Success could be summed up as commitment, belief, and flexibility.

Before leaving music strategies, here is a fascinating extract from a letter by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart about how he composed:

All this fires my soul, and provided I am not disturbed, my subject enlarges itself, becomes methodised and defined, and the whole, though it be long, stands almost complete and finished in my mind, so that I can survey it like a fine picture or a beautiful statue at a glance. Nor do I hear in my imagination the parts successively, but I hear them as it were, all at once. What a delight this is I cannot tell!

From a letter Mozart wrote in 1789, quoted in E. Holmes,

The Life of Mozart, Including his Correspondence,

Chapman and Hall, 1878

Do you have a good memory? This is a trick question because memory is a nominalization, you cannot see, hear or touch it. The process of remembering is the important thing. Nominalizations are actions that are frozen in time. Memory is static, you cannot influence it. Better to look at how you memorize, and how you can improve.

What is your memory strategy? How would you memorize the following sequence? (And pretend for a moment it is very important to retain it.)

DJWI8EDL42IS

You have THIRTY SECONDS STARTING NOW . . .

Time's up.

Cover the page, take a deep breath and write down the sequence.

How did you do? And more importantly, whatever your success, what did you do?

Twelve digits is beyond the capacity of the conscious mind to retain as separate units. You need a strategy to chunk them together in a smaller number of blocks to remember them all.

You may have repeated the sequence over and over again to form a tape loop (Ai). Tape loops last only a very short time. You may have recited it rhythmically. You may have written it out (Ke). You may have looked at it carefully and seen it again internally (Vic), as you looked up to your left. Perhaps you used color or another submodality to help you remember your internal picture.

Pictures are retained in long-term memory, tape loops in short-term memory. If you use this little test on someone you know, you will probably be able to tell what strategy they are using without asking. You might see their lips move soundlessly, or see their eyes scanning it over and over. Perhaps they smile as they make some amusing connection.

One thing that is very helpful, is to give this random sequence some meaning. For example, it might translate into Don Juan (living in Wisconsin) 8ed (hated) L (hell) for (4) 21 Seconds. Spending your half minute giving it some meaning is a good way of memorizing. Good because it accords with how the brain works naturally. If you made a mental picture of Don Juan in Hell etc. you will probably be unable to forget the sequence until the end of this chapter, however much you try in vain.

Robert Dilts tells a story about a woman describing her strategy in a demonstration workshop. The sequence was: A2470558SB. She was a Cordon Bleu cook. First, she said, it started with the first letter of the alphabet. Next came 24: the age she qualified as a chef. Next was 705. That meant that she was five minutes late for breakfast. The 58 was difficult to remember so she saw it in a different color in her mind. S was on its own so she made it big: S. And the last letter was B the second of the alphabet, linking with A at the beginning.

Now . . . cover the book and write out that sequence of letters and numbers. Don't forget the one that was bigger than the others . . .

You probably did well. And you did not even try. If you can remember that without trying what could you do if you tried?

A lot worse. Trying uses mental energy and the word itself presupposes a difficult task and probable failure. The harder you try, the more difficult it becomes. The very effort you use becomes a barrier. A good efficient strategy will make learning easy and effortless. An inefficient strategy makes it hard.

Learning to learn is the most important skill in education, and needs to be taught from reception class onwards. The educational system concentrates mostly on what is taught, the curriculum, and omits the learning process. This has two consequences. First, many students have difficulty picking up the information. Secondly, even if they do learn it, it has little meaning for them, because it has been taken out of context.

Without a learning strategy, students may become information parrots, forever dependent on others for information. They are information enabled, but learning disabled. Learning involves memory and understanding: fitting information into context to give it meaning. Focus on failure and its consequences further distract students. Everyone needs permission to fail. Good learners do make mistakes, and use these as feedback to change what they are doing. They keep their goal in mind and stay resourceful.

Marks and grades have no effect on the strategy a student uses. They are merely a judgment on the performance, and serve only to separate students out into a hierarchy of merit. Students may try harder with the same ineffective strategy. If learners were all taught a range of good strategies, then large differences between them in performance would disappear. Teaching efficient strategies would improve the results of all the students. Without this, education functions as a way of ordering people into hierarchies. It keeps the status quo, labels the sheep and the goats, and sorts one from the other. Inequality is reinforced.

Teaching involves gaining rapport, and pacing and leading the student into the best strategies or ways of using the body and mind to make sense of the information. If students fail and continue to fail, they are likely to generalize from performance, to capability, to belief and think that they cannot do the task. This then becomes a selffulfilling prophecy.

Many school subjects are anchored to boredom and unhappiness, and so learning becomes difficult. Why is education often so painful and time-consuming? Most of the content of a child's full-time education could be learned in less than half their time at school if the children were motivated and given good learning strategies.

All our thinking processes involve strategies, and we are usually unconscious of the strategies we use. Many people use only a handful of strategies for all their thinking.

Spelling is an important skill, and one many people find difficult. You get credit for creative writing, but not for creative spelling. Robert Dilts teaches the process that good spellers use and has organized it into a simple, effective strategy.

Good spellers nearly always go through the same strategy, and you may like to check this if you do spell well or you know someone who does. Good spellers look up or straight ahead as they spell; they visualize the word as they spell it, and then look down to check with their feeling that they are correct.

People who spell poorly usually try to do it from the sound. This is not so effective. Spelling involves writing down the word, representing it visually on paper. The obvious step is first to represent it visually internally. English words do not follow simple rules where the sound corresponds to the spelling. In the extreme case “Ghoti” could be a phonetic spelling of “fish”—“gh” as in cough; “o” as in women and “ti” as in condition. A phonetic spelling system cannot even spell its own title correctly.

Good spellers will report seeing a mental image of the word with a feeling of familiarity. They just feel that it looks right. Copy editors who have to be expert spellers just have to look down a page and they report that wrong spellings seem to jump out at them.

If you want to be an expert speller, or if you are already, and are interested in checking what you do, here are the steps of the strategy:

There are some helpful ideas you can use with this basic strategy:

This strategy was tested at the University of Moncton, New Brunswick in Canada. A number of average spellers were split into four groups. A spelling test was set up using nonsense words the students had never seen before. The first group (A) was shown the words and told to visualize them while looking up and to the left. The second group (B) were told to visualize the words, but not told any eye position. The third group (C) were simply told to study the words in any way they wished. The fourth (D) were told to visualize the words looking down and to the right.

The test results were interesting. Group A showed a 20 percent increase in correct spellings on previous test results. Group B showed a 10 percent increase. Group C stayed roughly the same as you would expect, they had not changed their strategy. The scores of group D had actually worsened by 15 percent, because they were trying to visualize, using an eye accessing position that made it extremely difficult to do so.

Good spelling is a capability. If you follow this strategy you will be able to spell any word correctly. Learning lists of words by rote may help you to spell those words but it does not make you a good speller. Learning by rote does not build capability.

This spelling strategy has been used with success on children that have been labelled as dyslexic. Often these children simply are more auditory or kinesthetic than other children. Wun wunders why foenick spelling methuds arr stil tawt in skools.

I prefer to entertain people in the hope that they learn, rather than teach people in the hope that they are entertained.

Walt Disney

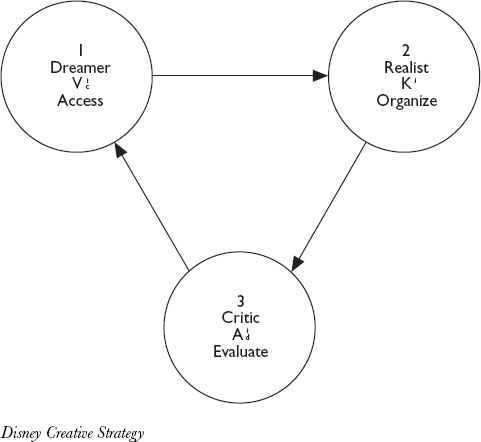

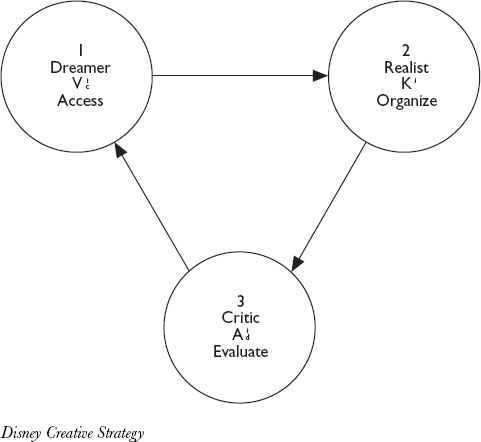

Robert Dilts has created a model of the strategy used by Walt Disney, a remarkably creative and successful man, whose work continues to give pleasure to countless people all over the world. He would have made a fine business consultant, because he used a general creative strategy which can be used for any type of problem.

Walt Disney had a wonderful imagination; he was a very creative dreamer. Dreaming is the first step toward creating any outcome in the world. We all dream of what we want, what we might do, how things could be different, but how can we manifest those dreams in the real world? How to avoid the pie in the sky from turning to egg on the face? And how do you make sure the dreams are well received by the critics?

He first created a dream or vision of the whole film. He got the feelings of every character in the film by imagining how the story appeared through their eyes. If the film was a cartoon, he told the animators to draw the characters from the standpoint of those feelings.

He then looked at his plan realistically. He balanced money, time, resources, and gathered all the necessary information to make sure that the film could be successfully made: that the dream could become reality.

When he had created the dream of the film, he took another look at it from the point of view of a critical member of the audience. He asked himself, “Was it interesting? Was it entertaining? Was there any dead wood, regardless of his attachment to it?”

Disney used three different processes: the Dreamer, the Realist and the Critic. Those who worked with him recognized these three positions, but never knew which one Disney would take at a meeting. He probably balanced the meeting, supplying the one that was not wellrepresented.

Here is the strategy you can use formally:

When you are ready, step into the Realist position. You are anchoring your realist state and resources to that spot. When you have relived your experience, step back to the uninvolved position.

What you have done is to anchor the Dreamer, the Critic and the Realist into three different places. You can use three places in your workroom, or even three separate rooms. You will probably find one position is much easier for you to access than the others. You might like to draw some conclusions from this about the plans you make. Each of these positions in fact is a strategy in itself. This creative strategy is a super-strategy, three separate strategies rolled into one.

To make sure the criticism is constructive rather than destructive, remember that the Critic is no more realistic than the Dreamer. It is just another way of thinking about the possibilities. The Critic must not criticize the Dreamer or the Realist. The Critic must criticize the plan. Some people criticize themselves and feel bad, instead of using criticism as useful feedback about their plans. Sometimes the Critic comes in too soon and picks the dream or the Dreamer apart.

Some people use this strategy naturally. They have a special place or room where they think creatively, an anchor for their Dreamer. There is another place for the practical planning, and another for the evaluation and criticism. When these three ways of thinking are cleanly sorted spatially, each can do what they do best without interference. Only if the finished idea works in each place are they ready to act. At the end of this process you may well have a plan that is irresistible. Then the question is not “Shall I do this?” but, “I must do this. What else would I do?”

This is a good example of a balanced strategy. All three primary representational systems are involved, so all channels of information are available. The Dreamer usually operates visually, the Realist kinesthetically and the Critic auditorily.

There needs to be some external step outside the strategy in case the internal processing gets into a loop and goes nowhere. Here you have an outside position to review the whole process and call a halt in real time.

As we move out of strategies and go on to look at some other aspects of modeling, it is worth mentioning in passing one point that troubles some people.

There is a strange idea in our culture that finding out explicitly how you do something will interfere with doing it well, as though ignorance is a prerequisite to excellence. While you are doing a task, your focus of conscious attention is, of course, on doing the task. The car driver does not consciously think about everything she does as she is doing it, and the musician does not consciously keep track of every note she plays. However, both could explain to you afterward what it is that they have just done.

One difference between a competent performer and a master in any field is that the master can go back and tell you exactly what it is that he has just done, and how he did it. Masters have unconscious competence and the ability to make that competence explicit. This last skill is referred to as metacognition.

With metacognition, you have the possibility of becoming aware of how you perform a task. Knowing how you do something gives you the ability to pass it on to others. Also, by identifying the difference between what you are doing when things are going well and what you are doing when they are not, you can increase the likelihood of peak performance on an ongoing basis.

Exploring the process of modeling also raises questions of whom you model. This depends on the outcomes you are going for. You need to first identify the skills, competencies or qualities that you are most interested in acquiring. Then you consider who would serve as your best role-model.

The next question is how you go about modeling. There is a whole spectrum of possibilities, which range from the unconscious and informal modeling that we all do to the very sophisticated research and modeling strategies used by people like Robert Dilts in his recent modeling project for Fiat on leadership skills for the future. An informal and simple way to incorporate modeling skills in your development is to choose role-models from people you admire and respect. Alexander the Great modelled himself on an image he had of the legendary warrior Achilles, Thomas à Kempis had perhaps loftier ambitions when he wrote The Imitation of Christ. In more recent times, Stravinsky borrowed heavily from Mozart, claiming that he had the right because he so loved Mozart's music. Ray Charles modelled Nat King Cole, saying that he “breathed Cole, ate him, drank him and tasted him, day and night” until he developed his own special brand of musicianship.

By “breathing, eating, drinking, and tasting” your model, whether in books, television, or film, you will gain access to the kinds of states and mental resources that your model uses. If you are sitting down, try a little experiment. Most people sub-vocalize when they read, that is, they say the words aloud in their head as they read them. Notice what happens if you go back to the beginning of this paragraph right now and allow the voice in your head to transform into the voice of someone you really admire. For many people, just changing the voice inside their head to that of a role-model gives them access to new and different resources.

Often people get caught up in the mystique of modeling and think that it is something they cannot do until they have learned how to do it “properly”. But anyone who is curious about people cannot not do it! You do it already.

When I look back over the ten years since I first encountered NLP, I realize that most of my useful learning has come from informal modeling.

For example, I was visiting some friends recently and discovered for the first time that the lady of the house writes romantic fiction. She had been a little discreet about it, but in a half-hour social conversation I discovered some writing strategies that provided me with just what I was looking for. In brief, she used daydream time creatively to generate her material and jotted down keyword notes in a notebook she always carries. This reminds her of the content when she next sits down to write. She loves her creative daydreaming time, so it has a motivation strategy built in. Elegant.

You can be more sophisticated about modeling if you have identified a specific skill that you want to learn. Remember those three basic elements of any behavior: belief, physiology, and strategy. For example, to write this book, I need to believe that I can, and that it is worth doing. I need a set of strategies (sequences of images, sounds and feelings) with which to generate the content, and I need to feel comfortably relaxed as I sit and let my fingers dance on the keyboard.

If you wanted to enrich this minimal model, you would probably want to see me in action, or perhaps I should say “see me in in action”, since much of the process takes place unconsciously in the background as I do other things. You would probably want to ask me a lot of questions, some key ones being:

“In what context do you commonly use this skill?”

“What outcomes guide your actions in applying this skill?”

“What do you use as evidence to let you know you are achieving these outcomes?”

“What exactly do you do to achieve these outcomes?”

“What are some specific steps and actions?”

“When you get stuck, what do you do to get yourself unstuck?”

These questions are TOTE elicitation questions based on the TOTE model (Text-Operate-Text-Exit) in Chapter 4. The kind of model you are building is a system of recursively nested TOTEs or, to put it more simply, skills within skills, rather like a set of Chinese boxes, each contained within another.

With the answers to these kinds of questions you can start building a model of what I am doing with my nervous system. To know what questions to ask next, you run this model in your nervous system to find out what works and what is missing. This is rather like when someone gives you a set of directions to follow and you try them out in your imagination to see if they make sense.

There are many more skills to modeling than can be covered here or learned from a book. For example, you need good second position skills to penetrate the “wall of consciousness”. What is this wall of consciousness? At its simplest, when talented people try to explain or teach what they do, they discover that many of their skills are completely unconscious. It is as if the conscious scaffolding of the learning process has been taken away from the finished house, leaving no trace of how it was constructed.

At the other end of the spectrum from informal modeling is the full-blown high-quality modeling project usually done in the world of business. This involves having a full set of modeling skills at your fingertips. A typical sequence of events might be as follows:

Steps 1 to 5 are likely to take somewhere in the order of 20 days' work, with step 6 taking perhaps half as long again. This kind of back-to-back modeling-training package is very effective in organizations where the same work role is replicated many times over, for example, team supervisors or shop managers. Modeling without the training input is also beginning to be used in this country to fine tune the process of effective recruitment for specific work roles. Large organizations are beginning to appreciate the value of applied modeling.

This has been a brief introduction to modeling, ranging from the informal through to formal business projects. So here we are in the nineties with sophisticated modeling skills that all came from modeling language in the early days.

When Richard asked John to help him become aware of his Gestalt patterns, John approached it as he would approach learning a new language. To do a study of a language you did not speak was absurd. John had to be able to do the patterns before he could study them. This is the direct opposite of traditional learning, which analyzes the pieces first before putting it all together. Accelerated learning is learning to do something and only later learning how you are doing it. You do not examine the learning until it is stable and consistent and voluntarily available to you. Only then will it be stable enough to stand the scrutiny of the conscious mind.

This is a profoundly different way to learn than the four stages outlined in Chapter 1, which began with unconscious incompetence, and ended in unconscious competence. To start from intuition and then analyze is the basis of modeling and accelerated learning. You can go straight to unconscious competence in one stage. We have come a full circle from Chapter 1.

NLP began from a basis of intuition, rather like the way we learn our native language. Taking the whole study of excellence as the starting point, you can analyze all the way down to submodalities, the smallest building blocks of our thoughts.

What goes down must come up again. The analysis you have done ensures that you do not simply step up back to the place you were before. You emerge at a point of greater understanding. This stepping back up in a sense is coming back to the roots and knowing that place for the first time. This new point gives the basis for a whole new set of intuitions which can be stepped down again, and so the process continues.

You learn on each of these steps by testing each discovery to its limits. By using each idea or technique on every possible problem, you soon find out its true value, and where its limits are. Only by acting as if it works, do you find out if it does or not, and what its limits are.

First the Meta Model went through this process. Then representational systems, then eye accessing cues, then submodalities and so on. Each piece is pushed to its limit and the next piece takes its place. A constant loss of balance, followed by a constant rebalancing.

The value of NLP lies in the learnings you make in exploring these processes. The roots of NLP lie in the systematic patterns that underlie behavior. You do whatever it takes to create results, within ethical constraints, and then refine it to make it as simple as possible, so discovering the difference that makes the difference. The purpose of NLP is to increase human choice and freedom.

So as you are coming to the end of the last chapter of this book, you may already have started to wonder how to get the most from it. Each of us finds our own way of doing this and sometimes we don't even know we are doing it. One thing you may want to decide on a conscious level is whether you find this material interesting and useful enough to want to pursue it further, by buying books or attending training courses.

You may find yourself talking over the ideas with like-minded friends as you make sense of your new learnings and understandings. You may find yourself unexpectedly becoming more aware of some of the different patterns you have begun exploring, of rapport and subtle shifts in body language, of the dance of eyes as people think, of the delicate and profound shifts in your own emotional states and others. You may find yourself becoming increasingly aware of your own thoughts and thinking processes, noticing which ones serve you and which are mere ghosts of the past. You play with changing the content of your thoughts and you play with changing the form of your thoughts and you wonder at the impact as you discover how to create more emotional choice for yourself and others.

Perhaps you have already discovered the extraordinary effectiveness of developing the habit of setting outcomes, of thinking of problems as opportunities to explore, to do something different, and to learn something new and exciting.

You might have found yourself having more insights and intuitions into other people's realities, or being more grounded in your own. It is as though your unconscious mind is integrating your new learnings in its own time and way; a new relationship is evolving between your conscious mind and your unconscious wisdom. As though by rediscovering yourself, you are more aware of what matters to you and to the people that you are close to.

In listening to your own internal dialogue you discover yourself applying the Meta Model questions, you become increasingly curious as you discover more about your own own beliefs, and you continue changing the limiting ones to empowering ones that enable you to be more of who you always wanted to be.

In becoming increasingly aware of your own identity it seems as though you have far more choice than to be the slave of your past history. You think differently about your future and this influences who you are becoming in the present.

You may find a growing richness and intimacy in your relationships with your close friends and you may want to spend more time with other explorers of the rich world of human experience.

And as more of us become aware of how we make up our reality, we can begin to enjoy making it up more the way we would like it to be, so creating a better world for all.