Since ancient times it has been known that sleep is composed of both dreamless and dreaming phases. With the discovery that the electrical activity of the brain can be used to identify five stages of sleep, new areas in sleep research have opened up over the past forty years. This increased understanding has also led to the realization that the brain’s biological clock has a profound influence on our sleep pattern and, in particular, on the amount of time that we spend asleep. Furthermore, it is now known that the brain has special control centres which cause sleep and wakefulness to switch on and off.

In this chapter we consider sleep in the light of this relatively new wisdom, gaining an insight into our nightly pattern, and learning how this knowledge might help us to improve our sleep. We conclude with a self-assessment – only once we have analyzed the quality of our sleep, as well as our lifestyle and our environment, can we really set about improving it on a permanent basis.

It may seem an obvious point, but our body runs on cycles. We know this from simple experience – for example, the fact that we wake up in the morning and go to sleep at night, in a perpetual rhythm of action and inaction. However, we are also sensitive to several external cyclical patterns – in particular, the cycle of the seasons and the daily cycle of the sun. In order to fine-tune our sleeping patterns, we need to understand how these external, earthly cycles affect our inclination toward sleep itself. We start by looking at the impact the seasons have upon us.

The cycle of the seasons is a type of infradian rhythm (a cycle of more than twenty-four hours). The animals most affected by this are those that hibernate – with the onset of winter, they begin a prolonged period of dormancy, which enables them to survive the cold weather. Although we are not hibernating animals, we are also affected by the cycle of the seasons. During the night we produce the sleep-regulating hormone melatonin: the lack of light triggers the pineal gland in our brain to release it. This means that when the hours of darkness increase as winter creeps in, our melatonin production is stepped up, signalling to our body the seasonal change. The result is that we are naturally inclined to sleep for longer periods during winter (and for shorter periods during summer), and some researchers believe that this might even explain why many of us find it more difficult to get out of bed on winter mornings.

So, if we are having trouble sleeping, could we solve the problem by artificially increasing our melatonin levels? The hormone is available as a supplement in some countries. In the USA, melatonin is the only hormone that is not controlled by the US Food and Drug Administration; and it is taken widely there as a dietry supplement for its antioxidant and potentially life-prolonging properties. However, this is a powerful, regulatory hormone and, while it is clear that melatonin affects the biological clock, the jury is still out on whether it actually improves our ability to sleep. Either way, melatonin certainly should not be taken without adequate professional advice.

To help you to sleep well, it may be useful to become more aware of the effects that the seasons have on your body. Try to tune into their cycle – for example, watch not only how the leaves change colour in autumn, but also the myriad other little changes. Accept that you may feel especially sleepy during winter, and as far as is practical, allow your body to dictate your sleeping patterns. This will not mean that you will persistently oversleep during winter – you have an in-built biological clock, which partly regulates when you wake up. This, and the various other cycles which affect our sleep, are explained on the following pages.

In order for us to be able to keep time with the cycle of the sun each day, we have an internal timekeeper, known as the “biological clock”. In simple, neurological terms, this consists of a bundle of about 10,000 nerve cells, which are located deep in the brain near some of the main areas that control sleep and wakefulness. The nerve cells that make up the biological clock are also situated close to the optic nerves, which process information on the changing level of light perceived through our eyes.

Experiments have shown that the biological clock works on its own, roughly 24-hour cycle (in some people it is slightly longer and in others slightly shorter), and that the environment – in particular, changing temperature and fluctuations in light – serves to regulate the clock so that we all go to sleep and wake up on the same schedule, give or take a few hours. In other words, our environment sets the time, but the clock itself is pre-programmed and we would continue to have a roughly 24-hour cycle even if the sun never set and the temperature stayed at a constant level. Any 24-hour cycle is known as a circadian rhythm.

But what does this all mean for sleep improvement? Crucially, we need to determine whether our biological clock runs at a slightly slower or slightly faster pace than the cycle of the sun – that is, the 24-hour day. People who go to bed late and who consequently sleep through well into the morning have a biological clock running at a slightly slower pace than the 24-hour day – these people are often termed owls. Conversely, those who go to bed early but awaken early too have a biological clock running at a slightly faster pace – these people are termed larks. The box below helps to identify whether you are a lark or an owl – something you should bear in mind when you try to improve your sleep. For example, if you are an owl and you decide to go to bed an hour earlier than usual to try to get more sleep, you may well find that you spend that hour lying awake, worrying that you cannot sleep. Ideally, it would be more productive to allow your biological clock to dictate the amount of time that you spend asleep, while you take steps to improve the quality of that sleep.

If you think about your own tendencies, you can probably guess whether you are a lark or an owl, but to confirm your analysis why not ask yourself the following questions?

• Do you wake up bright and alert by 6am?

• Do you fall asleep quickly if you go to bed at 9pm?

• Do you find it hard to stay up until midnight?

If you have answered yes to all three questions you are a lark.

• Do you need to sleep until 11am to wake up bright and alert?

• Do you have trouble falling asleep before midnight?

• Do you fall asleep quickly if you go to bed at 1am?

If you have answered yes to all three questions you are an owl.

In the twentieth century much progress was made in our understanding of how the human brain functions. During the First World War, there was a global epidemic of encephalitis lethargica, commonly known as “sleeping sickness”. This debilitating disease, which killed approximately one million people, deeply affected sufferers’ sleeping patterns, resulting in total lethargy (and ultimately death). However, amid the human tragedy a great scientific discovery was made – neurologists were able to ascertain that special “centres” exist in the brain to control sleep, and that these partly counter-balance equivalent centres, which maintain wakefulness.

Physiologically, our sleep and wakefulness controllers are located deep within our brain, a fact that indicates that their functions, while vitally important, are very primitive. There are three or four such areas in charge of sleep and approximately double that number for wakefulness, ensuring that, if one part of the brain becomes damaged, there are plenty of other areas that can take over its work. Some of the sleep centres are found near the controls for other important but basic functions, such as the regulation of body temperature, metabolism and appetite – and all these things have an impact on our ability to sleep well.

If a person’s sleep centres are all active and their wakefulness areas are all inactive, they will experience a blissful state of sleep. However, if the person is disturbed – for example, by an uncomfortable bed, feeling too hot, experiencing pain or hearing a sudden noise – their wakefulness areas will be alerted. These, in turn, will activate other parts of the brain that determine whether the stimulus warrants further action. If the disturbance is regarded as important, such as the sound of a baby crying or the smell of smoke from a fire, yet more parts of the brain will be switched on, bringing the sleeper closer to wakefulness. If the disturbance is regarded as insignificant, most of the brain will stay dormant and we will not actually achieve conscious wakefulness. And if we do wake up briefly, we will not necessarily remember it because an insufficient portion of our brain would have been activated for full consciousness to return. Whether or not we actually wake up, in the morning we will probably feel that we have had an unrefreshing night’s sleep. From this we learn that our environment is a major contributor to the quality of our sleep – and a key to sleep improvement.

In order to comprehend fully how sleep works, we must first understand the distinction between consciousness and wakefulness. The French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650) famously wrote “I think, therefore I am,” and thus described consciousness: we are conscious beings because we have an awareness of self and our environment. But what happens when we sleep? We know that consciousness does not disappear because we dream (even if we do not remember our dreams) – which might be considered “thinking” sleep. Wakefulness, then, is the part of consciousness that is “full”, when we are wholly in control of our actions, and aware of the world around us.

Before we move on to study the unique physiology of the human sleep-cycle, we need a basic knowledge of the behaviour of our brain, as we enter the various stages of sleep.

The first recording of human electroencephalograms (EEGs) in 1924 by Hans Berger, which records electrical activity along the scalp, led to major advances in sleep science. EEG revealed that sleep is not a single, one-dimensional state, but rather a dynamic process during which the brain continues to respond to the environment and the internal functions of the body, while still overseeing the operation of sleep itself.

To get a better grasp of what goes on in our brain when we sleep, we need to look at the variations in the electrical activity of the brain at different times of the day, as well as of the night. When we are fully awake our brain activity is characterized by high-frequency, low-voltage brain waves called beta waves. The frequency of these waves varies according to the tasks that we are undertaking, as well as the amount of stress that we feel: the more active the task, or the more acute the stress, the higher the frequency of the beta waves. The waves gradually slow down as we become more tired toward the end of the day. Finally, when we relax with our eyes closed, beta waves turn into slower, relatively low-voltage alpha waves, which were discovered by Hans Berger. Then, as we become drowsy, the alpha waves become interspersed with even slower brain waves called theta waves. Drowsiness is a transition state – it lies between sleep and wakefulness. This is a time when we can easily return to wakefulness, but it is also a time when we might experience lifelike hallucinations, called hypnagogic dreams (see pp.48–9). However, if we are sleeping healthily, we spend only a short period in Stage 1 sleep – the transition period between wakefulness and sleep – and we soon produce the fast, short bursts of waves (as shown on the EEG) called sleep spindles (because they look like the spindles used by hand spinners). These herald the first true sleep state – Stage 2, in which we fully lose our awareness of the outside world. These sleep spindles soon turn into delta waves which are very large and slow and characterize both Stage 3 and Stage 4 sleep. These stages represent the deepest levels of sleep.

There is a fifth stage of sleep – that discovered by Nathaniel Kleitman and his assistant Eugene Aserinsky in 1952, and termed REM (rapid eye movement; see pp.42–3). This stage is usually seen as distinct from the other four stages of sleep, because our brain is highly active and the brain waves displayed on an EEG reading resemble those shown during wakefulness. When we are asleep we will typically progress through stages 1 to 4, and return to Stage 2 before entering our first period of REM sleep. The nature of this sleep cycle is explained further on the following pages.

Sleep is not a linear phenomenon. When we are asleep, we do not progress continuously through the stages of sleep from light (stages 1 and 2) to deep (stages 3 and 4) to REM sleep. Instead, we make journeys back and forth (sometimes lingering longer or less in one place), up to five times a night. Each journey is a completed sleep cycle, which, in an adult, has been found to last approximately ninety minutes. (In babies the cycle takes approximately sixty minutes to complete.)

In people who are not suffering from health problems, and who are not taking any medication, the first and second cycles of sleep consist mainly of deep sleep (stages 3 and 4), with perhaps five to ten minutes spent in REM sleep in the first, and fifteen to twenty minutes in the second. As the night progresses, and we enter our third cycle, we spend most of the ninety minutes in light sleep (stages 1 and 2) and experience more REM sleep than in the previous two cycles. The fourth and fifth cycles are dominated by REM sleep, interspersed with light sleep.

So how might this knowledge of sleep cycles help us to improve our sleep? Interestingly, experiments have shown that the ninety-minute cycle may not be confined to sleep – it can also be found when we are awake (see opposite). Research has indicated that around every ninety minutes during wakefulness our concentration wanders, the nostril through which we breathe more air switches (our nostrils never share the work equally!) and our energy levels drop. By identifying these low-points in the brain’s awake cycle and adjusting our bedtime to coincide with them, we may substantially improve our chances of falling asleep.

EXERCISE TWO

Using the following experiment, discover your own, waking ninety-minute cycle. Then, once you have established roughly the times when you are at your highest and lowest levels of alertness, make adjustments to your day. Try to undertake tasks which require most concentration when your cycle is at its peak, and go to bed at the low-point in your cycle, when you should find it easier to fall asleep. (As the experiment requires monitoring over a full day, it may be more convenient to conduct it at a weekend or on another day when you are not at work.)

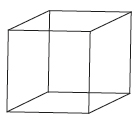

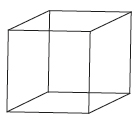

1. Use the image above to carefully trace or redraw the cube, to create a “portable” optical illusion. The cube, if looked at carefully for a period of time, will appear to switch the direction in which it faces – sometimes it will face downward as if toward the southeast and sometimes it will seem to point upward, toward the northwest.

2. Set an alarm to go off every 15 minutes throughout the day. Each time it rings, look at the cube. Time (by simple counting if you like) how long it takes for the cube to switch from one direction to the other.

3. After each occasion that you have looked at the cube, note down your “switch time”. The rapidity with which the cube switches reaches a maximum every 90 minutes. The closer you are to the low-point in your cycle, the quicker the cube will switch.

If we are healthy we should be able to fall asleep readily at the beginning of a ninety-minute cycle. Although identifying this cycle can be a great benefit in improving our sleep at night, other factors also affect our ability to go to asleep, which is actually a complicated process. To be able to fall asleep easily we have to rely upon our brain to switch off our wakefulness controls and at the same time to activate our sleep centres. In people who are not stressed, have not been overly active before they go to bed, and who are without sleep problems, this process is automatic. When we enter the first stage of sleep (Stage 1), if we are healthy, our muscles relax and our eyes roll beneath our lids. But if, for example, we are stressed, our wakefulness controls tell our brain that our muscles are not in the appropriate condition for sleep, and we have conflict between the sleep and wake controls, which will only be resolved once we start to relax.

Think back over the last week – how easily did you “drop off” each night? On some nights you probably fell asleep almost immediately, while at other times sleep might have been more elusive. In the first instance, there would have been a rapid progression from wakefulness to feeling drowsy and then into light sleep. When you were having difficulty falling asleep, however, you would have drifted in and out of consciousness and your final loss of awareness – the moment when you actually crossed the threshold into sleep – probably seemed to take for ever. At such times, when our brains appear to hover on the edge of awareness, many of us remember experiencing weird, dreamlike visions. These fragmentary images occur in a state known as hypnagogia and are characteristic of Stage 1 sleep. What is more, the hallucinatory aspects of this sleep state can be so frightening that they have themselves been known to cause sleeplessness. (More rarely, similar experiences occur as we drift into wakefulness sleep – this experience is known as hypnopompia.) Although we cannot control hypnagogia or hypnopompia, it can help to know that they are a completely normal part of the falling-asleep process, and that any other apparently random experiences (for example, images of a loved one laughing, “hearing” the sounds of alarm bells ringing, and the common sensation of falling) are merely our imaginations playing tricks on us. Perhaps – more romantically – we might like to think of the visions as temptations from the dreamworld, inviting us to sleep.

When we finally succeed in falling asleep (and assuming that we average eight hours of sleep per night), we spend roughly 50 per cent of this time in light sleep. However, this is mostly made up of Stage 2 sleep. Our periodic return to Stage 1 is usually only fleeting and is characterized by a change in sleeping position – it is rarely significant enough for us to recollect having drifted into near-wakefulness.

When we are healthy in body and mind, and our sleep is healthy too, we usually move out of Stage 2 and into Stage 3 sleep within ten to fifteen minutes of trying to drift off. However, we normally spend very little time in Stage 3, and as soon as our brain waves have slowed down to comprise more than 50 per cent delta waves (high-voltage waves, oscillating at a rate of around one wave per second), we reach Stage 4 sleep – the deepest level of all. The first third of our sleep is mostly made up of Stage 4 sleep. The duration of each period of deep sleep becomes shorter as the night wears on.

The importance of Stage 4 sleep for our overall wellbeing is reflected in the fact that it takes precedence over the other stages. Experiments have shown that if we are deprived of sleep for one night we usually make up almost all the lost deep sleep on the following night (mostly at the expense of lighter sleep). Even if we are made to go longer without sleep – say, for two or more nights – practically the entire deep-sleep debt is recouped over the course of our next two or more nights of sleep.

Similarly, when the sleep patterns of constitutionally short-sleepers (people who have only between four and five hours of sleep every night but feel perfectly well) are compared with constitutionally long-sleepers (those who need around nine or more hours of sleep to feel well), it is apparent that both types spend approximately the same amount of time in deep sleep – around two hours in total per night.

If deep sleep, then, is the most essential stage of sleep and our bodies are programmed to ensure that we always eventually make up any deficit (see pp.44–5), we may wonder why we might still feel unrefreshed and tired on any given morning. The answer to this question is that although deep sleep is the most important for our actual physical wellbeing (scientists believe that crucial maintenance and restoration work is done to the body during deep sleep; see box below), our waking sense of wellbeing arises from learned feelings of wellness, which usually require us to have had complete, uninterrupted sleep, comprising all sleep stages. In particular, we know that REM or dreaming sleep has a profound role to play in our overall physical and, especially, our emotional wellbeing. We consider this sleep stage next.

When someone wakes us up and we feel temporarily disorientated, we often protest that we were “deeply asleep”. However, it is unlikely that we were in what is scientifically classified as deep sleep (Stage 3 or 4 sleep) as it is extremely difficult to be woken up during this part of the sleep cycle. Research has shown that this could be because deep sleep offers a guaranteed period during which the growth hormone can stimulate development in children and repair the blood cells and body tissue in adults. Recent evidence suggests that repairs to the brain as well as the body are carried out in this stage of sleep. If we are successfully roused from deep sleep, we may act as if we are intoxicated – behaviour known as “sleep drunkenness”.

If we look at the EEG reading of a person in REM sleep (rapid eye movement – so called because during this period of sleep our eyes dart quickly back and forth beneath our closed lids), the trace made by the EEG machine will resemble that of someone who is awake – in other words, the activity of our brain during REM is akin to that of wakefulness. Despite this brain activity and the movement of our eyes at this time, the muscles in almost all the other parts of our body (the exceptions being those that are essential to sustain life) become paralyzed. Because of the contrast between the activity of the brain and eyes and the paralysis of the muscles, REM sleep was once known as paradoxical sleep.

According to Hindu tradition there are three levels of consciousness: waking, dreamless sleep and dreamful sleep. The tradition goes on to say that, in order to live in balance and harmony, we must optimize our experience of all three. We might think that dreaming sleep is unimportant and view it as just a frivolous mode of expression for an overactive imagination – but by depriving subjects of REM sleep, scientists have been able to prove that if we do not dream we become irritable, vague and easily fatigued, and we display a poor ability to remember things. This discovery reinforces the knowledge that recouping REM sleep is a priority over recouping light sleep in order to ensure our overall wellbeing.

But why are our muscles paralyzed during REM sleep? The logical explanation seems to be that this is a safety precaution to prevent us from acting out our dreams, most of which occur during REM. Centres in the brain actively block the output from the centres that normally stimulate movement. This might also explain the common dream experiences of being unable to run or incapable of screaming – perhaps such dream sensations are the mind’s interpretation of the body’s physical paralysis.

A healthy, young adult has approximately two hours of REM sleep per night, which occurs mainly in the second half of our sleep period. The “depth” of REM sleep lies somewhere between light and deep sleep. If we are roused during the REM phase of our sleep cycle we tend to be coherent and able to report the dream that has just been interrupted. However, our memory of dreams usually fades quickly (probably because long-term memory storage takes place during REM and normal, waking memory processes are not themselves yet awake!). This means that the longer the interval is between the end of REM sleep and the time we wake up, the less likely it is that we will be able to recall our dreams.

As with deep sleep, if we are deprived of the REM stage, our body will try to make up the deficit by prolonging the time we spend in REM on subsequent nights. Interestingly, going without sleep for a protracted period can even cause REM brain activity (and dreaming) to occur when we are awake, suggesting that dreams may be vital for our psychological wellbeing. By exploring the nature of dreams we can learn more about the role they have to play in improving our overall sleep (see pp.122–5).

Now that we know about the cycles and stages of sleep, we are ready to set about assessing the quality of the sleep that we do obtain. However, just before we move on, there is one important thing to remember – sleep bounces back! There are times when our regular, twenty-four hour sleep–wake cycle is disrupted – sometimes for extended periods of time. For example, this might happen if we need to provide long-term care for someone who is ill, if we have a baby or if we work in an industry that sporadically requires us to work at night. Although we may feel nervous about the dangers of sleep debt, we should always keep in mind that the body has ways of ensuring that we get all the sleep we need: we already know that deep and REM sleep are made up at the earliest opportunity. (Constitutionally short-sleepers compensate for the short duration by foregoing most light sleep, gaining instead only two hours of deep sleep and two hours of REM.)

However, it would barely be sleep science if it were entirely that simple. There is, of course, a downside to our body’s remarkable and innate ability to claim back the sleep debt. If we are sleep-deprived, “unintentional” sleep (the kind that occurs when we should be awake) invariably descends upon us when we are doing something monotonous and boring. One of the most obvious examples is the drowsy, luring kind of sleep that threatens to overwhelm us when we make a long and tedious car journey, having started out feeling tired anyway. (Research has shown that doctors and nurses are more likely to be involved in road traffic accidents when they have worked an extended shift.)

As a species we would not have survived this long if conditions that constantly interrupt our sleep, such as looking after children, could have a devastating effect on us. Sleep has its own band-aid that any of us can take advantage of at any time – the nap. (Remember though, if you nap: it can take up to twenty minutes to awaken fully and your “performance efficiency” – the optimum level of alertness – lags behind your revitalized energy; and napping when we are not suffering considerable sleep deprivation can upset the normal working of your biological clock.)

The most important point here is: if you think you are losing sleep – don’t panic! Your body will make up any sleep debt and once you have been through this book and optimized the conditions for sleep, there will be every reason for sleep to be your faithful night-time companion.

We should not begin to think about improving our sleep without first establishing what is wrong with it and what aspects of our lifestyle affect it. Only one fifth of the world’s population enjoys perfectly healthy, restorative sleep. At best, the rest of us find ourselves falling asleep, say, as we read a book, and at worst suffer from a sleep disorder, such as insomnia or sleep apnea.

Begin by assessing your energy levels. Do you wake up feeling groggy or heavy-headed? Do you feel sleepy (or worse, fall asleep) at inappropriate times, such as during a meeting at work, listening to a lecture on the radio, or even watching your favourite television show, a good play or an exciting movie? Does your energy slump significantly after lunch? Do you wake up in the night? When you feel sleepy during the day, does the impulse feel all-consuming and almost uncontrollable? If you answered yes to most or all of these questions, your sleep quality is not as good as it could be. But do not worry – help is at hand!

We already know that there are three main conditions that affect sleep: mental and physical health and the sleeping environment. Listed opposite are a series of statements to help you assess your lifestyle and overall wellbeing. Note down whether they are true or false when applied to your circumstances. Any true statements can impair your ability to sleep properly, and you should prioritize these issues when beginning a sleep-improvement program. Then, look at all the other areas and take steps to deal with those too. Monitor your progress in a journal by noting when you go to bed, how long it takes to fall asleep, how long and how well you sleep, and how you feel when you get up.

assessing your mental wellbeing

• I am quick to lose my temper or become irritable

• I laugh less than I used to

• I find it hard to concentrate

• I often feel on edge and tense

• I often feel sad or lonely

assessing your physical wellbeing

• I exercise less than twice a week (a brisk walk of about twenty minutes counts as the smallest unit of exercise)

• I often feel lethargic or sluggish

• I drink more than the recommended number of alcohol units per week (ask your doctor for the exact figure)

• I sometimes find it difficult to breathe

• I often suffer from muscular pain

assessing your sleeping environment

• My mattress is lumpy/more than ten years old

• My bedroom is too cold/hot and stuffy

• I have a computer/television in my bedroom

• I have noisy neighbours/live on a busy and noisy street