4 Systems of Raw Material Procurement and Supply in the Neolithic of Northern Thrace During the Seventh to Fifth Millennia BC

Summary

This essay outlines petrographic and geochemical analysis of flint from three sites in northern Thrace and suggests that two principle sources of flint were being utilized, one local, the other from a greater distance, probably from a source in north eastern Bulgaria.

The region

The stone assemblages, included in this report, have been recorded in the region of northern Thrace. This is the territory, which is located east of the town of Plovdiv and the eastern Rhodopes, south of Stara Planina and the Sredna Gora Mountains and reaching the Black Sea in the east. Northern Thrace is separated from eastern Thrace by the present political border (Fig. 4.1). The European part of Turkey, known as eastern or Turkish Thrace, is bounded by the Black Sea and in the south by the Aegean. The valley of the Maritsa (Meric or Evros) River marks the western border. Within these areas, three key sites have been investigated, all dated to the end of 7th and first half of 6th millennium BC. These are the settlements at Karanovo and Azmak in northern or Bulgarian Thrace and Hoca Çeşme in eastern or Turkish Thrace.

Raw material procurement and supply during the Neolithic Period in Northern Thrace

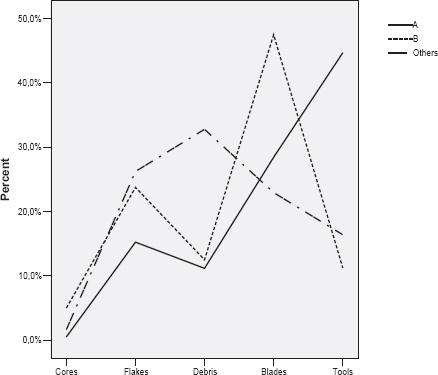

Until now the earliest evidence of Neolithic settlement in northern Thrace has been that associated with Tell Karanovo. The earliest Neolithic period in this area included Karanovo I and Karanovo II phases, which are dated to the first half of the 6th millennium BC as can the chipped stone assemblages from Early Neolithic layer at Azmak. About 60% of all artefacts from the Karanovo I and Karanovo II assemblages are made from raw material designated type A, of a yellow, or yellow – reddish brown color, not transparent, but with patterns of stripes or spots of various densities. More than 20 percent of specimens are made from raw material type B, the colour of which, in contrast, is highly variable, being dark grey, mid grey, beige grey, brown grey to red with irregular grey spots (Gatsov and Kurcatov 1997). It has been mineralogically analyzed by Dr. V. Kurcatov and the graphs (Figs 4.2 and 4.3) demonstrate similarity of raw material use between Karanovo I and Karanovo II.

Chipped stone assemblages from Azmak: the Neolithic Layer

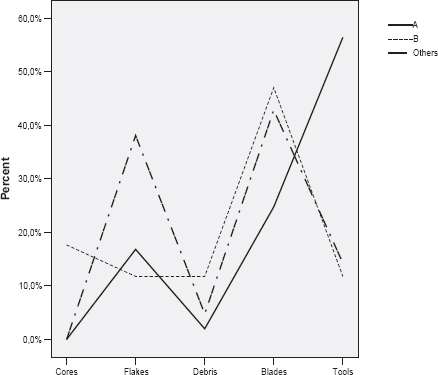

Recent investigations into the chipped stone assemblages from the early Neolithic layer, building levels V–I at Tell Azmak, using petrographic and geochemical methods produced interesting new results. Mineral composition, rock provenance, the origin and the probable source of the raw material were analysed and seen to correspond to the archeological data from Tell Karanovo, phases I and II (Gatsov et al. unpublished). Two thirds of specimens were made of raw material varieties 1 and 2, similar to the material used at Karanovo I and II – samples A and B. Analyses of the raw material samples were made by Dr. Vsevolod Kurčatov and his salient conclusions about the flint raw material from Karanovo I and II and the Neolithic layer at Tell Azmak are repeated here for convenience: first “the greater number of artifacts and raw material display a chalcedony-quartz composition (over 80%). Differing amounts of opal, clays, carbonate, ferric oxides and organic are also present as admixtures”. Secondly “the elevated content of SiO2 in the form of quartz, chalcedony and opal defines the basic raw material of the artifacts as chert”. Thirdly “the colour of the samples varies greatly and depends on the admixture quantity, as for example the organic imparts black colors, the ferric oxides – yellow to red and dark brown colours (jaspers), the clayey components – grey to black. A lack of admixtures leaves a semi-transparent or transparent appearance”. Fourth “the major part of heavily processed artifacts comprise opal, clays, carbonate, organic and ferric oxides, aside from frequently observed admixtures, chalcedony-quartz groundmass of gel to cryptocrystalline texture. It results in a lower relative firmness that makes pieces easier to process, preserving at the same time their basic qualities of cleavage that result in sharp cutting edges”. Fifth “the greater part of the artifact assemblage are of raw material varieties that have unrecognizable silicified detritus or preserved fossils which in turn provide evidence of their sedimentary origin”. Sixth “part of the (mainly non-processed) samples have an igneous origin or are of quartzite. It implies that they have come together with the raw materials by chance”. Seventh “the presence of many weatherworn crusts in the samples is evidence of the long duration of the weathering processes which are known to have taken place on the earth’s surface as well as in the soil layer and consequently it can be suggested that the raw materials have derived from the surface of natural outcrops”. Eighth “comparing the mineral composition and the characteristics of the stone assemblages with the rocks from the corresponding regions in Bulgaria (using geological data) it can be firmly suggested that the material is of regional origin, that is, they were obtained from southern Bulgaria”. Ninth “in order to prove convincingly the local origin of the raw materials, a detailed geological study and mineralogical investigation of the corresponding rocks is necessary in the presumed areas of raw material sources” (Kurčatov, in press).

Figure 4.2. Graph.

While no research related to the location of raw material sources has yet been undertaken, the presence of very high quality flint in all Early Neolithic assemblages in Northern Thrace is not in doubt. The flint is yellow, yellow-reddish to brown or grey in colour, opaque, with patterns of stripes or spots of varying density and it is not transparent. This type of flint has been found as relatively large blades in all sites dated to the first half of the 7th millennium in south and south west Bulgaria. Unfortunately, the precise location of flint outcrops or the locations of the workshops is still unknown. However, the idea that southern Bulgaria was a zone of supply during the early Neolithic period suggested by V. Kurčatov is not ruled out here. In this case, the existence of a relatively short and middle distance source of supply of the above mentioned high quality flint raw material can be suggested.

Figure 4.3. Graph.

Raw material procurement and supply in Northern Thrace: an example from Azmak, the Chalcolithic layer, building levels I–VIII

Within the boundaries of the study all chipped stone artifacts can be attributed to one of eight raw material varieties, including a burnt one (Gatsov et al. unpublished). All artifacts from building levels I–VIII were processed and in both periods – early and late Chalcolithic (designated as Karanovo V and Karanovo VI) almost two thirds of all artifacts were made of raw material varieties 1, 4 and 7. Varieties 2 and 6 were of a very low frequency in both periods. All burnt pieces are of variety 3. The assemblages from both periods display similar typological features. More than half of all retouched specimens were made of raw material samples 1 and 4. The remainder is of a smaller number of retouched pieces. In both periods, the most representative tool types such as blade end scrapers, retouched blades, blades with denticulated retouch and blade truncations were made of raw material varieties 1 and 4.

It is also worth mentioning the possibility of contact between the Chalcolithic settlements at Tell Azmak and some regions in north eastern Bulgaria, first suggested by V. Kurcatov’s analysis. This is based on raw material variety 7 from the Chalcolithic layer at Tell Azmak. Samples from the site alongside geological samples from the Razgrad region, north eastern Bulgaria were compared (Kurchatov in press) and the salient points repeated here: ‘The identical mineral composition of the samples, the similarities in the trace element contents and the textural analogy of the raw material give us reason to assume that the initial raw material (type 7) was taken from one and the same region.

Most probably the raw material used in the Chalcolithic layers at Tell Azmak originates from the northern cretaceous carbonate province (present-day north eastern Bulgaria – the area situated to the north and northeast of the Razgrad town). This province extends further north into present day Romania (Hansen et al. 2005, 341–393). Undoubtedly, i) ‘the raw material has a sedimentary origin – plant and animal silicified detritus is present’; ii) ‘the presence of corroded carbonate in all artifacts gives reason to conclude that the chert rocks resulted from silicification of primary carbonate sediments (formation of chert cores)’; iii) ‘the negligible variations in the Mn content is explained by its irregular distribution in the chert, whereas the elevated contents of Ca and Mn in sample No. 61 (quartz inclusion in the sample from Kamenovo) is explained by calcite relics and surface weathering enrichment of Mn-oxides. The latter explains the brownish color of the inclusion surface’; and iv) ‘in order to find out the exact location of presumed source of raw material, it is necessary to analyze a higher number of artefacts, which have to be correlated with the sample from the Razgrad region, north eastern Bulgaria’ (Kurčatov, in press).

On the basis of these points it can be suggested that blanks in the form of blade cores or/and blades were brought from present day northeastern Bulgaria to northern Thrace and notably to the area of Tell Azmak. Current analysis being carried out by LaPorta Associates should shed further light on this. In this case, it may be that two sources of raw material supply were utilized, one local the other from a greater distance. The longer distance supply derived from flint sources and flint workshops in north eastern Bulgaria where cores or/and blades were obtained and transported to northern Thrace. The local supply includes raw material extraction and core processing close to Tell Azmak or even on the spot.