EDUCATION AND PHILOSOPHY

INTRODUCTION

When Christianity became Rome’s official religion in the fourth century AD, it was the end of paganism, but not of pagan education, even after the break-up of the Roman Empire in the West in the fifth century AD. The point is that a romanized education had long been standard across the Empire, and because it fulfilled society’s secular needs, Christians had no problems with it. It both accustomed provincials to the Roman ways of doing things, and opened up, for those who wanted it, a route into the Roman political world.

The church was only too keen to take over an established, empire-wide system perfectly designed to help it spread its message among the young. After all, if Pliny the Elder was to be believed, the Roman system had already shown what could be done. Here he described Italy as:

a land which is the nurseling and mother of all other lands, chosen by the divine might of the gods, to make heaven itself more glorious, to unite dispersed empires, to temper manners, to draw together in mutual comprehension by community of language the warring and uncouth tongues of so many nations, to give mankind humanitas and, in a word, to become throughout the world the single fatherland of all peoples.

Changes in the system were made, of course, with much more emphasis on Christian teaching – the Latin Bible, the church fathers (for example, St Augustine). But pagan methods were still the focus. The priority here was given to what the Middle Ages called the trivium (tres, ‘three’ + via, ‘road’), the three ‘branches’ of literary/philosophical education – grammar (see here), rhetoric (p. 155) and logic; and teaching still concentrated on line-by-line technical linguistic analysis (see here). The quadrivium (four ‘branches’) – music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy – referred to mathematical education.

Cicero’s treatises on rhetoric were a key text; collections of passages were made from authors like Virgil and even Ovid that exemplified ancient wisdom about life and psychology in line with Christian teaching; and stories were told of pagan Romans, such as the ascetic Cato the Elder, who set good Christian examples. The justification for this was provided by St Augustine, who said:

If the philosophers chanced to utter truths useful to our faith, as the Platonists above all did, not only should we not fear these truths, but we must also remove them from those unlawful usurpers [i.e. pagans] for our own use.

St Basil used another image: rose bushes produce glorious flowers for picking, but we must avoid the (pagan) thorns. And that was what Christians did. Ancient philosophy was predominantly concerned with reasoned reflection about the morally good life, often springing from beliefs about the nature of the world and always open to question. The gods, being a product of nature, were not a driving force behind this moral existence; there was certainly no equivalent of an ultimate authority, such as the Bible. When the Christian Tertullian said, ‘I believe because it is impossible’, he was rejecting the whole intellectual classical tradition. But that tradition was still behind the highly respected pagan education, and there was much that could be assimilated to Christianity – for example, Plato’s view of a morally good deity and Aristotle’s views of logic and language and the relationship between the natural and the metaphysical world. Thereby hangs a tale. First Aristotle wrote about ‘The Natural World’, ta phusika (τα φυσικα); and after that he wrote about the metaphysical world, ta metaphusika (τα μεταφυσικα), which meant literally ‘After [my book about] The Natural World’!

A central figure in the development of Christian education was Alcuin, from York (c. AD 735–804). Widely learned in classics, he was recruited by Charlemagne, who ruled much of Europe from AD 771 to 814, to help establish schools in all monasteries and cathedrals in his European ‘empire’ and raise the standards of education among the clergy. The result was the copying and editing of texts on a huge scale, ensuring the survival of large numbers of Greek and Roman authors.

A major shift occurred in the European Renaissance, from the late fifteenth century onwards. This saw a gradual movement away from technicalities to ‘humanism’, which used classical authors to help pupils understand people and man’s place in the world. The move was prompted partly by the re-emergence of Greek in the West.

This came about because, from the twelfth century, scholars in the Greek East in Byzantium became fearful of assaults by the Ottoman Turks. So they moved west, especially into Italy, and brought their precious Greek manuscripts with them, which had not been available in most of the West since the end of the Roman Empire there. Scholars had been aware of the Greeks’ achievements, of course, because Latin literature was full of them (see here); but their works had disappeared.

There was also renewed interest in, and so a search in libraries for, Latin authors, especially those like Cicero, with their interest in the best forms of government and man’s duties and responsibilities. In his Education for Boys (1450), the future Pope Pius II declared that, in reading these works of practical wisdom by the ancient and modern authors, ‘through zeal for virtue you will make your life better, and you will acquire the art of grammar and skill in the use of the best and most elegant words, as well as a great store of maxims’.

New interest in classical painting, sculpture and architecture accompanied this general revival. As a result, the learning of Latin and reading of Latin authors were embedded in school curricula all over Europe for around the next 400 years. For the rest of the story, see here.

EDUCATION

The Latin educatio meant the rearing of young or breeding of animals; it derives from the verb educo, ‘I support the growth of’, used of offspring, animals and plants. It was not used of systematic education in our sense largely because there was no such thing in Rome. Teaching was done by parents – we hear that Cato the Elder taught his son reading, law and athletics, to throw a javelin, fight in armour, ride a horse, box, endure heat and cold, and swim – and private tutors. The litterarius (‘letters man’) taught basic reading and writing and numbers; then for the pupil aged about nine, the grammaticus polished up those skills, teaching mainly poetry and Greek; then at around the age of fifteen, the rhêtôr (Greek ῥητωρ, Latin rhetor: see here) taught the arts of political and legal persuasive argument. Much of this would involve the use of history and its precedents, myth and its examples, philosophy and so on. Repetition and learning by heart from a young age were strongly emphasized.

Interestingly, the Latin word tutor had nothing to do with teaching; he was a guardian or protector, originally someone appointed to look after a person considered unable to manage their own affairs. The term derives from tutus, ‘safe’, from the verb tueor (tuit-), ‘I catch sight of; watch over, protect’. Our ‘intuition’ derives from intueor, ‘I fix my gaze upon, consider, contemplate’, though nowadays it means ‘instant understanding, without proper thought’.

SCHOOLS FOR LEISURE

Since education was designed for those committed to public life, it was largely the domain of the elite (eligo [elect-], ‘I extract [of weeds]; I pick out, select’). First, it had to be paid for; second – and far more significant – you had to have the time to indulge it. When most of the population had to make their own living as best they could, whether off the land or in some form of private endeavour, a structured education was largely irrelevant: it was all hands to the pumps on the farm or in the forum (see here). Only the wealthy, living off the profits of their land, could afford the luxury. Our ‘school’ reflects this, being derived from the Greek for ‘leisure’ – skholê (σχολη). For Romans, the word for ‘elementary school’ was ludus, ‘sport, play, show, frivolity’ (whence ‘ludicrous’, and so on).

PUPILS, PUPPETS AND POPPETS

Pupils may often feel like captives of their tyrannous teachers, and they would be right, at least linguistically. The emperor Nero knew the feeling. Madly in love with Poppaea, he could not divorce his wife Octavia because of his mother’s disapproval. Poppaea rounded on him, calling him a ‘pupillus, dependent on someone else’s orders, in control neither of your empire nor your freedom!’

Latin pupa meant ‘girl, doll’, and the diminutive forms pupilla and pupillus were used, respectively, of girls and boys under the care of a guardian, as Poppaea accused the emperor of being. So our ‘pupil’ is an appropriate name for one under the care of a teacher. Another term for ‘pupil’ was discipulus, ‘one who learns’, requisitioned by the church, as in ‘disciple’. That comes from disco, ‘I learn’, as in disciplina, ‘instruction, branch of study, orderly conduct’. This could become physical. Romans had no problem about this as long as it was purposeful. Tacitus said disapprovingly of the Germans that they were accustomed to kill their slaves not to maintain discipline and strict standards (severitas) but out of impulse and rage (ira).

When we talk of inculcating good habits, for example, we are using the Latin inculco (inculcat-). Its root meaning was ‘I stamp in with the heel’ (calx [calc-], ‘heel’). That will show them!

EYEING PUPILS

The diminutive pupilla had in Latin another meaning, at it does in English: ‘pupil’ as in ‘pupil of the eye’, the hole in the centre of the iris which looks black but through which light can hit the retina. Apparently it is so called because when you look in another person’s eye, you see a diminutive reflection of yourself. Pliny the Elder commented that ‘when a man lets go of a bird, it will usually make straight for his eyes because it sees there an image of itself which it knows and wants to reach’.

Vulgar Latin spelled pupa ‘puppa’, and because it meant ‘doll’ as well as ‘girl’, it is the source of our ‘puppet’ and the endearment ‘poppet’.

LEARNING YOUR GRAMMAR

The pupil confronted with a Latin text was trained to analyse it in minute technical detail. This would include everything from dividing words up into syllables (see here), pronouncing them properly and parsing them, to writing them, analysing the metre of a poem, reading aloud and so on. Outlandish words were chosen for this exercise, e.g. knaxzbikh (κναξζβιχ) – whatever that meant. Our ‘parse’ derives from the question: ‘Quae pars orationis?’ ‘What part of speech?’ Only much later in a pupil’s education were texts mined for anything other than technicalities, such as historical and moral content, and then only for the purpose of learning to produce a really persuasive speech.

DOSITHEUS’ GUIDELINES

There survives from the fourth century AD a collection of material, some produced by one Dositheus, some ascribed to him, some by others, illustrating how Latin was taught to Greek speakers.

It consisted of a series of colloquia (→ our ‘colloquial’), simple everyday ‘conversations’ in Latin translated into Greek word for word; explanations of the alphabet; discussions of grammar, such as the case system, i.e. nominative, accusative and so on; lists of different types of noun; conjugating verbs, from Latin coniugo, ‘I marry up’ (the different parts); vocabulary lists; words with multiple meanings; and passages from Latin authors.

One manuscript shows that Romans transliterated Latin into Greek to help Greeks learn Latin, just as this book transliterates Greek into English before giving the Greek. So Latin feliciter (‘good luck!’) is transliterated as φιλικιτερ (filikiter).*

THE CASE SYSTEM

Latin and Greek are ‘inflected’ languages (Latin inflecto, ‘I bend, modify’). That meant many of the words changed their shape to reflect the job they did in the sentence (English ‘I’ and ‘me’, ‘he’ and ‘his’, etc.).

Nouns changed their endings to do this. So Latin servus meant that ‘slave’ was the subject of the sentence; servum that he was the object; servi meant ‘of the slave’; and so on. So servus servum servi videt would mean ‘the slave sees the slave of the slave’ – and so on. These different forms of the noun were called ‘cases’, and when you listed them in order, you ‘declined’ them.

CASES OF FALLING OVER

The terms for grammatical cases derive from Latin, though Greeks, of course, had got there first. Aristotle’s word for ‘case’ was ptôsis [πτωσις], ‘falling, modification’, whence Latin casus (cado [cas-], ‘I fall’) and so ‘case’. This ‘falling’ image was taken literally: the ancients envisaged the nominative, nominativus – the ‘naming’ case (or subject of a sentence) – as ‘at the top’, and the other cases falling away from it sideways (whence Greek engklisis [ἐγκλισις], ‘leaning’ = declinatio, ‘declining’, whence our ‘declension’).

The vocative, vocativus, ‘for calling’, was used for addressing people. The genitive, genitivus, ‘giving birth’, was the equivalent of Greek genikê [γενικη], ‘generic’ (represented by English ‘of ’). The dative, dativus, ‘giving’, corresponded to Greek dotikê [δοτικη], ‘giving’ (English ‘to’ or ‘for’). The accusative – accusativus, ‘accusing’, from aitiatikê [αἰτιατικη], ‘produced by a cause, effected’ – indicated the direct object of a sentence. The ablative case – ablativus, ‘that from which something is taken away’ (English ‘by, with or from’) – was unique to Latin and first mentioned by Quintilian. The Roman antiquarian Varro (116–27 BC) called the ablative the ‘sixth case’ or the ‘Latin case’.

NUMBERS

We owe our alphabet to the Greeks and Romans. It is a relief that we owe our numerals to the Arabs. You try multiplying XXXVI by MDCCCXCVIII.

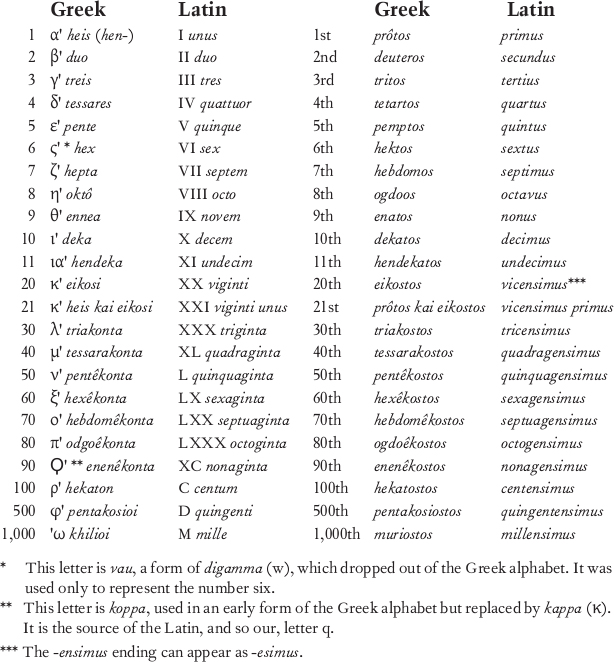

Below is a chart with basic Greek and Latin words for numbers, many of which will be familiar. It will help to explain primary, secondary and tertiary education, decimal, the mile (a thousand paces), September to December, the octave, Pentecost, quarts, Deuteronomy (nomos [νομος], ‘law’), the Septuagint, quarantine (from quadraginta, the number of days a potentially infected person would be kept isolated) and trivial (Latin trivium was where three roads met, basically a street corner, a place of no importance). Juvenal satirized know-all women who banged on about politics, soldiering and world affairs:

How cities are tottering, lands subsiding,

and tells everyone she meets all about it at every street corner.

Scientists will recognize ‘proton’ and ‘deuterium’, whose nucleus is called ‘deuteron’. But not ‘neutron’: this derives from Latin neutrum, ‘neither’, given a Greek ending (-on) to look like the others.

Geometricians will know the Greek for ‘corner’, gônia (γωνια). This gives us all those geometric shapes with different numbers of corners, such as pentagon, hexagon and polygon (‘many-cornered’: polu [πολυ], ‘much, many’).

Really big modern numbers have been given modern help from the ancient Greeks, or at least from their vocabulary. Numbers in the millions are mega (μεγα, ‘big’); in the billions they are giga (γιγας, ‘giant’); and in the trillions they are tera (τερας, ‘monster’).

Incidentally, Latin secundus is so called because it follows primus (Latin sequor [secut-], ‘I follow’).

COMPUTING MATHEMATICAL CALCULATIONS

It was Pythagoras (it seems) who first suggested that there was a mathematical harmony to the universe, as if number and ratio in some sense lay at the root of everything. From this came the idea of the cosmic ‘harmony of the spheres’ (see here). The Greek mathêma (μαθημα) meant basically ‘lesson, learning’, and then ‘mathematical science’; arithmos (ἀριθμος) meant ‘number, counting’ and then ‘arithmetic’.

The Romans took over both these words (mathêmaticus, arithmêticus) but also gave us ‘calculus’. For Romans, calculus meant ‘small stone, pebble’ (also used for juggling), but specifically a pebble used to make calculations on a counting board, and so ‘reckoning, account’. Calculatores were people who taught arithmetic. The poet Martial urged calculatores and teachers of shorthand to forget about pupils during the sweltering, mosquito-ridden days of summer: ‘They’ll learn enough if they just keep well.’

For ‘making a calculation’, Romans used computo (computat-), ‘I calculate, reckon up’. A ‘reputation’ derives from reputo, ‘I reckon up, reflect on, consider’; another meaning (somewhat ironical these days) is ‘I make allowances for expenses’, which the reputable are always very careful not to massage.

DIGITAL WORLD

Pliny the Younger mentioned a court case he conducted about a contested inheritance, and said at one stage he had to do some calculating (computo), and ‘practically demanded pebbles and a board’ (calculos et tabulam) to do it. He also talked of a man ‘moving his lips, twiddling his fingers…’ as he does his sums (computat). Nothing new about the digital world, then (digitus, ‘finger’).

VOTING PEBBLES

For us, ‘calculus’ has a very specific mathematical meaning and was first used in the 1660s. The Greek for ‘pebble’ was psêphos (ψηφος), and pebbles were used for voting in the courts. Hence our ‘psephology’, the study of voting, or elections.

GRAMMAR SCHOOLS

Our ‘grammar’ derives ultimately from Greek gramma (γραμμα), ‘letter of the alphabet’, a noun formed from graphô (γραφω), ‘I write’ (whence the ‘graphite’ in your pencil). From this Greeks created grammatikos (γραμματικος), an adjective meaning ‘good scholar, grammarian, critic’. Romans turned this into a noun, grammatica, meaning ‘the study of literature and language, including its explanation critically and grammatically’. This emerged in Old French as gramaire, and so our ‘grammar’.

The original grammar schools from the sixth century AD – scolae grammaticales – taught Latin mainly to train people for the church, and Latin (with Greek) remained at the heart of grammar school curricula for another thousand years: it was the language of education. In the process Latin grammar came to be thought of as providing the definitive systematic account of the rules of language, to which every language should conform, however uneasy the fit (see here).

It ought to be said here that in Rome the top teachers of language and literature at the advanced level could command gigantic salaries. After all, it was the key to political success. One such teacher (born in slavery) was bought for 700,000 sesterces, another was paid 400,000 sesterces a year to teach.

THE GLAMOUR OF GRAMMAR

Not many pupils would think of grammar as an alluring subject, but words have always been felt to hold some mysterious, even bewitching power (see here); and the Scottish word ‘gramarye’, derived from ‘grammar’, meant ‘magic, enchantment’ and then ‘magical beauty’. Many consonants readily change to ‘r’ (called ‘rhotacism’, after the Greek letter rho, for example ‘got a lot of ’ becomes ‘gorra lorra’). So ‘gramarye’ became ‘glamer’, with the spelling ‘glamour’ the final result.

THE COURSE OF LIFE

Our ‘curriculum’ was taken over from Latin curriculum. Curro meant ‘I run’ (→ our ‘current’), and curriculum meant ‘running, race, racetrack’ and also ‘course of action, way of behaving’. But, rather like most modern school curricula, Latin curriculum had nothing to do with education. Nowadays, your curriculum vitae is supposed to reveal how you have run the race of life.

THE LANGUAGE OF GRAMMAR

Ancient Greeks invented much of the grammatical terminology that we still use today. The Greek words were translated into Latin by excited Roman grammarians. The Roman encyclopedist Varro was among the enthusiasts: his reaction to Greek research was to write the twenty-five-volume De lingua Latina (‘On the Latin language’), of which five books survive. These terms came into our language via Norman French. The chart below gives some examples.

| Greek | Latin | English |

| onoma, ‘name’ | nomen | noun |

| rhêma, ‘what is said’ | verbum | verb |

| epi-rrhema, ‘in addition to what is said’ | ad-verbium | adverb |

| ant-ônumia, ‘in-place-of noun’ | pro-nomen | pronoun |

| sun-desmos, ‘binding together’ | con-iunctio | conjunction |

| pro-thesis, ‘placing before’ | prae-positio | preposition |

| metokhê, ‘sharing’ (i.e. the function of a verb and noun/adjective) | participium | participle |

The language of tense (past, present, etc.), voice (active, passive, etc.), transitive/intransitive, mood (imperative, subjunctive, etc.), case names (nominative, accusative, etc.) and so on all originated in the classical world.

GROVES OF ACADEME

Looking back at his past, the Roman poet Horace (first century BC) talked of a brief spell of ‘higher education’ in Athens ‘seeking truth in the groves of Academus’ (silvas Academi). It was brief because, following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC, civil war broke out between Caesar’s supporters Octavian and Antony (the eventual winners) and the assassins Brutus and Cassius. Horace joined the losing side.

But who, or what, was Academus? He was the mythical Greek hero Akadêmos (Ἀκαδημος; alternatively Hekadêmos) and was said to have originally owned the area, about a mile north-west of Athens. His bit part in myth was very small: when Theseus and Peirithous had stolen the young Helen (later of Troy) from Sparta with a view to one of them marrying her, Akadêmos revealed her whereabouts to Helen’s brothers, the gods Castor and Pollux. In the sixth century BC, the area was walled in, trees were planted and it became a public park. Plato bought a piece of property nearby and taught there or in the park: hence Plato’s Akadêmeia, our ‘academy’, ‘academic’ and so on.

PHILOSOPHY IN LATIN

Horace went to Athens to finish off his education, as did many other Romans, including the Roman statesman Cicero, and that meant philosophy. There is a good reason why Greeks were the philosophers: they invented the subject and the language. It was Cicero who took the Greek and latinized it, providing us with a range of Latin options.

In some cases, the Greek word was simply written in Latin, such as philosophia from φιλοσοφια. The Greek meant ‘love’ (φιλο-) + ‘cleverness, intelligence, learning, wisdom’ (σοφια, → ‘sophist’). Cicero debated how to translate Greek sôphrosunê (σωφροσυνη), ‘moderation, self-control’: ‘Sometimes I call it temperantia, sometimes moderatio, sometimes also modestia. But I do not know whether this virtue could better be termed frugalitas…’

SOME PHILOSOPHICAL TERMS

As a result of the efforts of Cicero and others, the following technical terms came from Greek via Latin into English:

•Greek êthikos (ἠθικος), ‘to do with ethics’, became in Latin moralis (see here), our ‘morals’.

•Greek philanthrôpia (φιλανθρωπια), ‘love of mankind’, became humanitas.

•Greek epistêmê (ἐπιστημη), ‘knowledge’, became scientia, our ‘science’.

•Greek hormê (ὁρμη), ‘energy, impulse’ (p. 283), became appetitus (animi), our ‘appetite’.

•Greek ousia (οὐσια), ‘unchanging reality’, became essentia, our ‘essence’.

•Greek poiotês (ποιοτης), ‘what-sort-of-ness’, became qualitas, our ‘quality’.

•Greek idiôma (ἰδιωμα), ‘special character, unique feature’, became proprietas, our ‘property’ in a philosophical sense (‘what is the property of electricity?’).

But in another sense, idiôma meant ‘special use of words’, as in our ‘idiom’. It was formed from idios (ἰδιος), ‘one’s own, private, personal’, while idiôtês (ἰδιωτης) meant ‘private person, layman’. This drifted into meaning ‘someone of no professional skill at all, ignorant, uneducated’, as it did in Latin idiota. And so, ‘idiot’!

ETHICS

Many philosophical schools of thought sprang up and became subjects of higher education. Ethical behaviour was at the heart of all of them. This is such a hot topic these days that it is educative to learn that originally the word had nothing necessarily to do with humans at all. Greek êthos (ἠθος) meant an ‘accustomed place’, and in the plural êthea (ἠθεα) related to the usual abodes not only of humans but of such things as lions, fish, plants, and even the sun. Herodotus reported that, according to the Egyptians, in the course of its history ‘the sun on four different occasions moved from its accustomed place, twice rising where it now sets, and twice setting where it now rises’. The term became focused on humans in the sense ‘manners, customs’, and then ‘character’.

This is essentially what Aristotle meant when he talked about ethics. The question for him was what makes a good human being; and by ‘good’ he meant what we mean by (for example) a good, functioning, successful car. Goodness (in that practical sense) of character was one issue – courage, modesty, fairness, and so on; goodness of the intellect was another – knowledge, intelligence, judgement, etc. Man was also a social animal, knowing what was just and unjust, good and bad. That too was all part of being successful.

STOICS

Ancient philosophy was not pie-in-the-sky theory. Its aims were ethical – to show adherents how to lead the good life (Latin vita beata, → ‘beatitude’); it was also holistic (Greek holos [ὁλος], ‘whole’) because the good life was thought to depend on the physical nature of the universe.

‘Stoicism’ derived from the Greek stoa (στοα), the portico in Athens where from 300 BC its inventor Zeno (a Greek from Cyprus) taught this branch of philosophy. His ideas were based on the belief that (i) in a sense the universe was God, and God was the universe; (ii) to that extent, everything was fated; (iii) the divine element in the world was reason (logos [λογος]); and (iv) the whole material world was permeated by logos – ‘like honey through a honeycomb’ – including our souls (Latin animus, or anima), the divine in us. So if we wanted to align ourselves with the divine – which would presumably make us happy – we should exercise logos, the reasoning faculty. Logos was the key to a happy life. Material rewards and worldly success were irrelevant.

Logos gives us ‘logic’ and all the ‘-[o]logies’, which mean ‘giving a rational account of ’. So ‘biology’ means giving a rational account of bios (βιος), ‘life, living things’. The Latin for ‘reason’ was ratio (see here). It meant ‘the act or process of reckoning, explanation, (exercise of) reason’. In the chaos after Julius Caesar was assassinated, Cicero wrote despairingly to his friend Atticus: ‘We must leave everything to fortuna, which counts for more than ratio in such matters.’

DANGEROUS EMOTIONS

If logos enabled us to lead a happy life, what could stop it? The Stoic answer was: the emotions – anger, fear, pride, grief, desire, even (to take it to extremes) pity and love. Deal with those, and happiness should be yours. But if everything was fated (see above), what chance did you stand? A favourite Stoic image was that of a dog on a long leash tied to a bullock cart. There was nothing the dog could do to stop the bullock going where the bullock wanted. So: the dog could travel its destined course by acting rationally in line with the divine logos, and so go freely and happily (though being on a long leash, it had a degree of leeway); or by acting irrationally, it would struggle and be miserable. ‘Restrain yourself and endure’, said the Stoic thinker Epictetus.

Emotio was not a Latin word, but in the sixteenth century the French invented émotion, derived from Latin emoveo (emot-), ‘I shift, dislodge, displace’ – which is certainly what the emotions can do to you.

JUSTIFYING SLAVERY

Stoicism was a dogma embraced by many Romans, but it brought its own problems with it. The founder of Stoicism, Zeno himself, argued that all forms of subjugation were evil, and therefore both slavery and empire – the exercise and maintenance of power over other states – were morally wrong. Other Stoics agreed: ‘Justice instructs you to spare all men, to respect the human race, to return to each his own, not to touch what is sacred, or what belongs to the state, or what belongs to someone else.’ The argument was extended by later Stoics to embrace the idea that humans were naturally bound to one another by a code of law; for one man to use another merely for his own benefit was to break that natural, mutual bond.

Roman Stoics therefore had to reverse the trend of Greek thinking if they were to justify Rome’s imperial ambitions. The defence of empire began from the proposition that slavery was in the interests of certain kinds of men who, if left to their own devices, would only damage those interests, for instance by robbery or civil disorder. A properly administered empire, however – that is, one driven by moral concerns – would ensure such injustices did not take place. In certain cases, therefore, the subjugation of a people was justified – on condition that the imperial power acted morally and had the well-being of its subjects at heart.

EPICUREANISM

The belief that Rome had been divinely ordained to rule the world was strong. Virgil in his Aeneid, a canonic work of literature for the Romans, described Jupiter as affirming that he ‘had given Rome rule (imperium) without end’.

Yet Epicurean philosophers saw no room for deities. The Greek Epicurus (Epikouros, Ἐπικουρος) had taken on board atomic theory (Greek atomos [ἀτομος], meaning ‘unsplittable’). It was invented by the Greek philosopher Democritus in the fifth century BC. Atomos referred to the small, indivisible particles out of which, Democritus speculated, the whole universe, including the gods, was constructed; and their movement through the universe was random and irrational. So there were no such things as controlling gods or providence.

AN ATOMIC UNIVERSE

In his marvellous poem ‘On the Nature of Matter’, the Roman poet Lucretius (first century BC) showed with almost religious fervour how atomism explained everything without recourse to divine agency – from gods to man, from sex and sight to dreams, thunderstorms and earthquakes. In particular, since from atoms we come and to atoms back we go, the soul or life force (anima, → ‘animal’) must also be made of atoms. It disintegrated in death with us. Therefore there was no afterlife and nothing to fear in death; and further, gods had no interest in the activities of humans. Not that Lucretius used atomus: he preferred semina rerum, ‘seeds of matter’, from semen (semin-), which gives our ‘seminal, inseminate’ and ‘seminar’, where ideas are seeded; and primordia rerum, ‘very beginnings, elementary stages, of matter’, whence our ‘primordial’ (see here for ordo).

By contrast, with intense disgust in his voice, Lucretius described how religio persuaded Agamemnon, leader of the Greek army against the Trojans, to lead his very own weeping daughter Iphigeneia as a sacrifice to the altar and personally cut her down, in order to get the wind that would enable the Greeks to sail to Troy: ‘Such monstrous wickedness could religio incite.’

FROM ATOMS TO MOLECULES

Lucretius was unlucky. His work vanished from sight for hundreds of years, largely because Aristotle’s theory that the main constituents of the cosmos were earth, air, fire and water ruled the roost. This was the ‘four-element’ theory – five if you add aithêr (αἰθηρ), the element filling the external universe. But in 1417 a manuscript of the poet was discovered in a library in Germany. Its contents became known to thinkers who had come to see that Aristotle’s theory was nonsense and were grappling to find a better one. By the seventeenth century atomic particle theory had started to come to the fore – where it remains to this day.

In 1678 this new particle theory spawned the term molecula. It was derived from the Latin moles, which, bizarrely, meant ‘a gigantic mass’ (giving us our ‘mole’, a huge breakwater to hold back the sea). The -cula ending, however, is a diminutive, so molecula should mean ‘a small gigantic mass’. Naturally, no Roman would ever have envisaged such an idiotic word. Anyway, the result was the gradual development of the idea that atoms combine to form molecules.

SCEPTICS

If people are ‘sceptical’ about, say, global warming, it is understood that they do not believe it, or have severe doubts about it. That indicates quite a shift from the original meaning of the word. The Greek verb on which ‘sceptic’ is based is skeptomai (σκεπτομαι), ‘I watch out, look about carefully, examine, consider’, while skeptikos (σκεπτικος) meant ‘thoughtful, reflective’. In Homer’s Iliad, the Trojan hero Hector retreated from battle, ‘watching out for the whistle of arrows and thud of spears’. When some Athenian representatives in Sparta heard the Corinthians (allies of Sparta) denouncing Athens and saying Sparta should attack at once, the Athenians defended themselves, ‘because the matter needed to be considered further and not decided on the spot’. In other words, it had active connotations: the matter was up for serious debate.

The change came about with the invention of the philosophy known as ‘Scepticism’ by the Greek Pyrrho (c. 360–270 BC). In it, he suggested that it was impossible to understand the real nature of things, either because the world itself was shifting and indeterminate, or because we were just not able to understand it, however much we might try. So there was not much point in bothering, and we might as well live as untroubled a life as we can, unconcerned about all these matters. His biographer said: ‘He led a life consistent with this belief, taking no precautions against anything – dogs, carts, precipices – and was kept out of harm’s way by his friends.’ He was happy to take things to market, and do the cleaning in the house. He once washed a pig.

Rather surprisingly, because Romans were very interested in this philosophy, the word scepticus does not appear in classical Latin. Romans talked instead of Pyrrhonei, followers of Pyrrho.

COSMOPOLITAN CYNIC

Acting like a dog: that was the accusation made against the Greek thinker Diogenes (c. 400–323 BC), who came from a Greek colony in Sinope on the Black Sea coast. Greek kuôn (κυων) meant ‘dog’ and kunikos (κυνικος) meant ‘dog-like, canine’; Romans turned it into cynicus, from which we derive ‘cynic’.

The reason for the accusation was that Diogenes appeared wholly unconcerned about behaving in accordance with normal human standards. Uninterested in theoretical or philosophical problems, he believed humans were basically primitive beings with an overlay of civilized sophistication that was quite inappropriate to their real nature or interests. Abandoning all commitment to family, state or convention, he declared himself a citizen of the world (kosmopolitês, κοσμοπολιτης). He lived in a large earthenware container and believed in self-sufficiency, freedom of speech and indifference to hardship. He had no interest in worldly goods and thought money the mêtropolis (μητροπολις, ‘mother-city’) of all evils.

DIATRIBES AND QUOTATIONS

All of these philosophers are better called lifestyle gurus. They were in competition with each other, and all of them churned out treatises to argue their cases. But those treatises, being composed on papyrus – a vegetable substance which lasts only about eighty years – would survive only if they were copied and recopied down the ages (see here). Many were not. The Greek for ‘treatise’ was diatribê (διατριβη), whence our ‘diatribe’. That word has competitive overtones. Many an ancient diatribê certainly felt like that too.

But although much is lost, we often know something about these people because quotations from lost works frequently appear in works that do survive, such as encyclopedias, dictionaries and accounts of ancient lives. To take an example: Diogenes Laertius (third century AD) wrote the lives of eighty-two philosophers, of whom only five today survive in whole books; make that four if you discount Socrates, who wrote nothing but whose dialogues were ‘written up’ by Plato. Diogenes refers in all to 365 books by a total of 250 named authors, as well as 350 anonymous ones.

‘Quotation’ is not a Latin word, though it is based on one: quotus, meaning ‘having what position in a numerical series?’, ‘bearing what proportion?’ (compare our ‘quota’). From the sixteenth century ‘quote’ was used to mean ‘mark with numbers in the margin’ and so ‘cite, refer to’.

* Note the confusion of ‘i’ and ‘e’, due to some merging of these sounds at this late date.