Introduction

Overview

Misty Buchanan

To the untrained eye, the Piedmont of North Carolina doesn’t seem to offer as much plant, animal, or geological diversity as other regions within the state. After all, compared with the beautiful Appalachian Mountains and the vast Coastal Plain, it’s hard to see how the Piedmont could “stack up.” North Carolina’s biggest cities and highways are in the Piedmont, and about two-thirds of North Carolina’s human population live in the middle third of the state, which roughly corresponds to the Piedmont region. This area has been settled, explored, and exploited intensively for 300 years. Can there really be much nature left there? The answer may surprise you. In North Carolina’s Piedmont, biologists continue to discover species that are entirely new to science and rediscover some species that once were thought to be extinct.

The rolling hills of the Piedmont lie between the Blue Ridge Mountains in the west and the Coastal Plain in the east. The low hills that characterize the Piedmont are the remnants of ancient mountains that were formed during several large-scale geologic events as the continents were shifting. Over hundreds of millions of years, these ancient mountains eroded to form the Piedmont, and wide rivers carried sediment downstream to the Coastal Plain and, ultimately, into the Atlantic Ocean.

The rivers and streams of the Piedmont region are especially important ecologically. These waterways harbor a diversity of aquatic species, including some endemic organisms that exist nowhere else in the world. The Neuse River waterdog is an aquatic salamander whose entire earthly existence is concentrated in only fifteen individual populations in the Neuse River Watershed. The endangered Cape Fear shiner is a small fish that is known only from the Piedmont portion of the Cape Fear River drainage, relying on shallow turbulent waters for suitable nursery and spawning habitat. The endangered mussel species, the Carolina heelsplitter, is found only in the waters of the Catawba and Pee Dee river basins. The presence of rare and endemic fish, mussels, and amphibians in Piedmont rivers indicates that water quality here remains pristine enough to support these animals that are considered sensitive to pollution and sedimentation. The presence of these animals also indicates healthy ecosystems, where natural riparian zones, the borders between land and water, are functioning properly to protect water quality, reducing turbidity, erosion, and pollution.

At the southern border of the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions, the Sandhills supports rare and endangered longleaf pine forests, one of the most richly diverse natural communities in the world. Longleaf pine forests historically ranged from northeastern North Carolina to Texas and depended on frequent, natural fires and wetland hydrology for survival. The fact that these sensitive species can coexist with North Carolina’s largest cities within the same region is something of which North Carolinians can be proud. Careful planning of the economic growth and development of our state will allow us to achieve a sound, prosperous economy while still maintaining these important ecosystems.

Piedmont Geology

April C. Smith

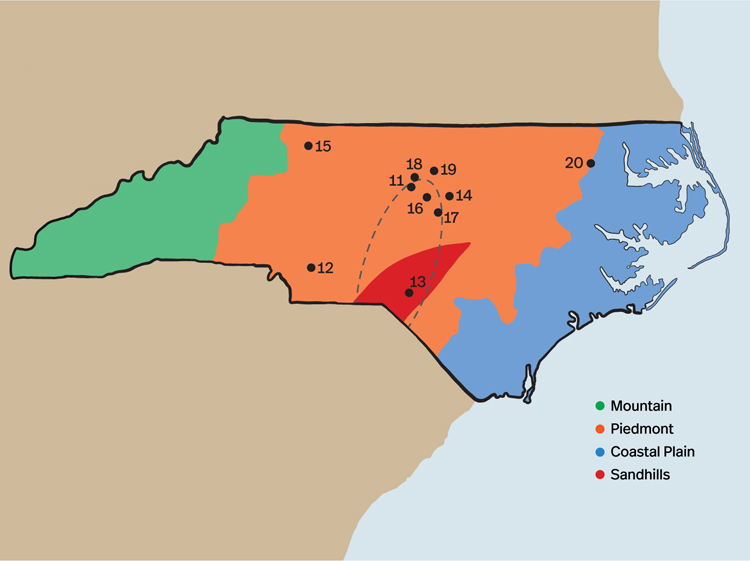

The North Carolina Piedmont has a somewhat violent geologic history that might surprise you: ancient volcanoes and giant rift basins helped form what is now the center of our state. The Piedmont region is not as old as the Mountain region; the rocks that you find in the Piedmont are between 600 million and 200 million years old. Like the rocks in the mountains, the Piedmont rocks also are igneous and sedimentary, and most of them later underwent metamorphism from intense heat and pressure deep inside the Earth. About 500 million years ago an ancient sea called the Iapetus Ocean existed between what is now North America and Africa. Evidence of the ancient seashore sands can be seen at Pilot Mountain. Between 480 million and 260 million years ago, a series of three landmass collisions occurred where volcanic islands were caught and squashed between the landmasses. These collisions added blocks of crust to the eastern edge of North America, creating mountains and causing metamorphism. As these collisions brought North America and Africa together to form the supercontinent Pangea, the Iapetus Ocean was slowly being squeezed out of existence. Pangea existed for ~100 million years before breaking apart. As it did so, the land ripped, leaving giant ditches called Triassic basins stretched across the Piedmont. You can see where these basins existed on the Piedmont region map on p. 107. Today the Piedmont is rolling hills and plains, farmland and rivers. If you look closely, you will see that the extraordinary geologic history of the Piedmont has left us with hidden ecological gems that beg to be explored.

Map 3. Exploration locations in the Piedmont region of North Carolina. The dashed line represents the approximate location of the Triassic ditches that were ripped into the land when Pangea broke apart (see the Piedmont Geology section). Map by Ashleigh M. Smith.

11 Haw River

12 Reed Gold Mine

13 Sandhills

14 Prairie Ridge Ecostation

15 Pilot Mountain State Park

16 North Carolina Botanical Gardens

17 Hemlock Bluffs

18 Occoneechee Mountain State Natural Area

19 Eno River State Park

20 Medoc Mountain State Park