CHAPTER 1

An album of war

The visual mediation of the First World War in Danish magazines and daily newspapers

The press of countries at war loses its capacity to reflect a nation’s life, the soul of a people. … What it omits saying, or has to omit saying, remains just as difficult for the future writer of history to uncover as it is difficult for him to find a thread in what is being said. But even so he must get a strong impression of the power and importance of the press from the press telegrams of the war.1

From a media perspective, the First World War was a crucial turning point for the modernization process of the Scandinavian press that was already underway. ‘The First World War has been called the last great newspaper war—on the other hand, it changed the newspapers more than any previous war had done,’ according to the latest Swedish history of the press.2 The increase in the circulation of the daily and magazine press continued during the war, during which there was a great demand for the latest news. When it came to supplying news, the First World War was a large-scale testing ground for a Western European, and ultimately global, news network—something for which the spread of the telegraph network and the international telegram agencies’ communications work and market sharing had laid the foundation in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In relation to the typological shift of the Scandinavian daily press from party newspaper to omnibus newspaper—which had not been introduced until the first decade of the twentieth century and was far from complete—the war’s stream of telegrams accentuated the journalistic focus on news. At the same time, the war coverage meant a modernization of newspaper layouts: front pages were cleared of advertising material; headlines spanned more than one column; war material was edited thematically as a separate topic; and—as will be examined more closely in this chapter—visual mediation through the use of photographic material intensified, especially in the daily press (the magazine press having already gone over to the almost exclusive use of reproduced photographs). The Norwegian media historian Tor Are Johansen also views the 1910s as the ‘definitive breakthrough’ for photographs in Norwegian newspapers—although he does not mention the importance of the war in this connection.3 The photographic mediation of the war was not, however, an internal media concern but also, to an even greater extent, part of the propaganda war being waged by the powers involved. The First World War, thought of as photograph album, therefore marks a coming together of journalistic priorities and propaganda interests.

Photojournalism and image reproduction techniques

The visual representation of the First World War in the Scandinavian media was determined by the development of photojournalism, the network of sources, and the state of reproduction technology, as well as the various forms of state censorship of news media.

Photojournalism only started to develop seriously in the interwar years, but the publication of war photographs was known from the mid nineteenth century onwards (notably from the Crimean War and the American Civil War).4 Media coverage of the First World War, however, produced a veritable flood of images, which is why coverage of this particular war marks a crucial turning point in relation to both photojournalism and film reproductions of war.5 Not without reason has the First World War been characterized as the first mediated war in history on a number of counts, because those involved no longer stood opposite one another, face to face, but had media interposed between them, both in the form of such war technology as long-distance weaponry and by virtue of the fact that warfare was dependent on information conveyed by visual media, including aerial photography: ‘the urgent need that developed for ever more accurate sighting, ever greater magnification, for filming the war and photographically reconstructing the battlefield’.6 The visual media were not only of tactical importance in the war, but also part of the soldiers’ understanding of it:

The presence of photographers and cameramen changed the situation on the battlefield. The soldiers now all started to pose for the photographers and take part in mock battles in front of the cameras. Out of this developed a specific representational aesthetics of war, in which the reality of the action was staged on the basis of its communication by the media.7

Visual representations themselves became a war zone, and at the same time the visual mediation of the war was assessed as a fundamental change in the ‘visual mechanisms of observation’8 and an objectifying ‘industrialization of the capacity for observation’.9 The army leaders on both sides admittedly tried to control the flow of images as best they could, but in the long run this was difficult since not only official photographers but also common soldiers took photographs. British newspapers even organized competitions among the soldiers for the best war pictures.10

The motifs of the photographs that were published can be seen at a general level as presentations of national myths, with stereotypical conceptions of patriotism, heroism, and national solidarity as the crucial selection criteria for the photographs that found their way into the daily and weekly press, while the horror of war was underplayed.11 As sheer propaganda, the war photographs at the start of the war presented a fairly stereotypical iconographic pattern, with motifs consisting of troop parades, cheerful soldiers marching past enthusiastic crowds, and military vehicles setting off for war.12 The visualization of war as an imaginary reality without much contact with actual conditions was particularly maintained in the images in the German press, while the British press changed course after the Battle of the Somme, when it began to depict the horror of war. In the French press the brutality of war was also less glossed over than in the German press.13

The state of reproduction technology during the war was very unusual, particularly as far as the daily press was concerned, because it was in the middle of a transitional phase from drawings and xylography (printing from detailed engravings on wood) to photographic images, and because telegraphed pictures were still only a technical possibility. Since the 1860s, experiments had been carried out with picture transmission by telegraph,14 and in 1908 an event was organized in connection with the launch of a Berlin– Copenhagen–Stockholm picture telegraph connection, over which the Danish newspaper Politiken and the Swedish Dagens Nyheter had the right of disposal for Scandinavia.15 It was not until the 1920s, however, that the use of phototelegraphy really came into its own, which is why the 1920s are thought of in terms of the media and photojournalism as ‘the decade of the flood of images’.16 In 1921, the American telegraph company Western Union transmitted its first halftone photograph, followed by the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) in 1924, and the radio organization RCA’s ‘radiophoto’ in 1926. At the same time, international telegram agencies such as Associated Press started to set up actual picture services, whereas the German telegram agencies such as Wolffschen Telegraphen Büro and Telegraphen-Union took longer in developing the picture side of their activities.17 But since the 1890s, even before the international picture agencies began to dominate the market, picture agencies had been springing up at the major illustrated weeklies and independent stereotyping and electrotyping establishments, offering a diverse stock of plates for xylography, drawings from photographs, and halftone reproductions of photographs.18 These picture agencies, in Western Europe at least, had developed an exchange network of sorts.

There is not much to suggest that the Scandinavian press had actually made use of the technical potential for telegraphic picture transmission that opened up in 1908. There is, on the contrary, certain evidence to suggest that the use of news photographs, particularly in the daily press, had yet to oust the use of drawings.

FIGURE 1: Drawing based on a photograph. ‘The picture reproduces a photograph taken immediately after the explosion of the bomb.’ Note the signature in the bottom right-hand corner. (Politiken, 2 October 1914) (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

Even so, it is evident that newspapers and weekly magazines not only included what were definitely drawings from foreign press material showing the war, but that some of the illustrations in the newspapers were drawings based on photographs. Although it had been technically possible since the 1890s to reproduce photographs as halftone pictures, twenty years passed before newspaper photographs really gained a foothold, whereas the magazine press exploited the possibility of reproducing photographs much earlier.19

In the initial phase of the war, Politiken featured a number of drawings based on photographs. This may have been due to the fact that they were based not on photographs (positives) of sufficient quality to permit reproduction, but on foreign newspaper and magazine illustrations of such poor quality that they could only be made use of if they were converted into line drawings.20 ‘The picture is taken from a German magazine and is undoubtedly genuine’, or ‘The above picture is based on a photograph’ are typical explanations for heavily touched-up photographs, which could just as well have been reproduced as drawings.21 Quite apart from the issue of the technical quality of the reproduction, it should be borne in mind that line drawings (black-line or white-line cuts) were both quicker and cheaper as illustrations than autotype (halftone or greytone). Nor should it be underestimated that in 1914 there was still great prestige attached to illustrating. When Politiken moved to its present building on City Hall Square in Copenhagen in 1912, the newspaper had no fewer than five illustrators on the payroll—and only one press photographer.

There is another dimension to the question of newspaper illustrations, however: certain newspapers used very few of any kind. In certain circles, the use of photographs in newspapers still met with certain resistance, as they regarded the use of pictures rather than the information density of the printed word as the end of civilization as they knew it. So it was not until 1913 that the paper of the Conservative upper middle class, Berlingske Tidende, carried any form of illustration (and that was a drawing), nor until precisely 1913–14 that its first photographs appeared.22 This attitude was typical of the time, with illustrations in newspapers being associated with the yellow press, whose readers were perceived as being virtually illiterate. As Walter Lippmann (1889–1974) put it, in his reflections on the propaganda efforts of the media during the war, this was an attitude that verged on a principle in emphasizing the immediate realism of the photograph and its effortless accessibility:

Photographs have the kind of authority over imagination to-day, which the printed word had yesterday, and the spoken word before that. They seem utterly real. They come, we imagine, directly to us, without human meddling, and they are the most effortless food for the mind conceivable. … on the screen the whole process of observing, describing, repeating and then imagining has been accomplished for you.23

The transitional forms of reproduction in the visual mediation of the First World War also indicate that the photograph possibly does not mark the definitive breakthrough at all for media visualization—that it should be looked for far earlier, when it became possible to include illustrations printed from woodcuts. Especially when it came to the illustrated weeklies, this change took place in the latter half of the nineteenth century, and photographic reproduction by comparison was merely a technical innovation, not the decisive step we tend to consider it today, because we are easily tempted to ascribe a different truth value (the reality effect) to a photograph than to drawings and xylography. During the war, there was a certain amount of drawn material in Illustreret Familie-Journal, while Illustreret Tidende and Hver 8. Dag, as news magazines, were more oriented towards the use of photographic material. There are signs that the transition from drawings to photographs was still fluid in 1914, that the media had not yet come down decisively in favour of photographs, and that when it came to the development of a printed visual media culture, xylographic news pictures in the weekly press and drawings in the daily press were probably just as decisive as turning points in media history as was photographic reproduction.24

The flow of information and press legislation

With the outbreak of the war, the existing order in communications collapsed. As regards telegraphy, Germany was isolated by the Allies, since the underwater telegraph cables were destroyed. All telegraph traffic was therefore diverted round Germany and sent through neighbouring countries, with Denmark and Sweden included among the intermediate stations. In all the Scandinavian countries, the war was the cause of an enormous increase in telegraph traffic, and in each country there lay a hub of the European telegraphic network—there were in fact two such locations in Denmark (in Fredericia and Copenhagen).25

FIGURE 2: ‘Main telegraph station. Where, during the war, work continues at full speed both day and night.’ (c.1918, Post & Tele Museum, Copenhagen).

Apart from the reciprocal telegraph connections between the Scandinavian countries, Denmark as the southernmost country was directly linked to Germany, Britain, France, and Russia (via the Baltic island of Bornholm)—thanks largely to the cable route of Store Nordiske Telegrafselskab. The cable route to Germany (Gedser–Warnemünde) was severed on 4 August 1914, and in November 1914 two direct cables to Russia were shut down. Two further cables between Denmark and France were shut down in September 1917, and later one of the two cables to Britain was also shut down. The connection to Russia was re-established by routing telegraph traffic through Sweden.

Postal connections were also affected by the war. Transit mail through Germany stopped, although direct mail between Germany and Denmark was maintained. This meant that all mail from Britain, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and so on—including photographic prints and newspapers and magazines—reached Denmark by boat (and was thus exposed to unrestricted submarine warfare from 1917).

With regard to censorship, Britain had good reason to control trade with Denmark, so that Germany could not in this way acquire special resources, for example, horses from Iceland, or rubber from the US.26 The key censorship measures, however, were directed against telegraphic information about the war itself, which for the warring parties stemmed from the wish to control information and propaganda alike. It was, however, not only at the sending but also the receiving end that censorship was imposed in the Scandinavian countries. At the main telegraph station in Copenhagen, all telegrams from both foreign agencies and the newspapers’ own correspondents were subject to censorship, and conferences were held (in Gothenburg on 17–18 December 1917 and in Stockholm on 11 September 1918) where the Scandinavian countries attempted to arrive at common measures for telegram censorship. For both telegraph communications and the printed press it was the questions of military information, trade information, and explicit expressions of opinion about the countries waging war, which constituted the battleground for state and press on the boundaries of freedom of speech on issues that involved foreign powers.27 As avowedly neutral countries, it was important for the Scandinavian governments that the media did not come down on the side of any of the combatants, which in certain quarters was itself regarded as a blow against freedom of speech.

In Denmark, the daily press came to an informal agreement with the government in August 1914 not to mention troop movements and not to adopt a partial attitude toward the belligerents. A few newspapers, however, did not stick to the agreement, and in 1915 the government found it necessary to introduce proper legislation in the form of a temporary Press Act which made it punishable either to cast doubt on the neutral attitude of the state authorities in relation to commercial initiatives or ‘to incite the population against a nation at war’.28 Similarly, the Swedish foreign office sent out a communiqué to the press the day before war broke out which stated that the newspapers should strive to ensure that ‘announcements and statements about events in the war were formulated completely objectively and without taking the side of any of the warring factions, and to avoid any offensive remarks about them’.29 In the Scandinavian countries, then, there was press legislation that mainly focused on regulating public access to possibly critical treatments of each state’s balancing act between commercial policies and neutrality, where the foreign flow of information concerning the progress of the war attracted attention to the extent that publication in the newspapers of special pleading on the part of one of the warring parties could be perceived as a breach of what was in principle a neutral attitude.

Censorship also applied in principle to photographs and drawings, but the media in the neutral, Scandinavian countries found themselves in a situation where they received nothing but visual material that had already been approved by belligerents’ censorship authorities. At the beginning of the war, the army leaders of the respective countries refused to give press photographers access to the fronts, but gradually they too came to realize the importance of being able to control the visual mediation of the war, which led them to employ their own war photographers. However, the photographers’ limited freedom to operate is less interesting in the present context, where the focus is on the nature of the images that found their way into the Danish daily and weekly press, and so contributed to constructing the First World War as a visual reality. In that perspective, it is also worth noting that the flow of pictures and range of motifs was not only limited by censorship; photographic techniques, and in particular the picture conventions and genres that the illustrated weeklies and sentimental genre painting had cultivated in the latter half of the nineteenth century, also influenced the visual construction of the war and barred the development of photographic realism in press photography.30

Pictures of the war

During the first years of the war, the coverage was so massive that the media primarily passed on information on the course of the war, while other material was deemed less important. Week after week, month after month, the front pages of the newspapers were full of telegram material from the warring factions. In the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter, the amount of foreign material increased fivefold during the autumn of 1914, making up 30 per cent of the editorial copy in November.31 A survey of one Copenhagen newspaper (Politiken) and three local newspapers in the city of Odense (Fyens Stiftstidende, Fyns Tidende, and Fyns Social-Demokrat) shows, however, that war coverage shrank from 40–50 per cent of the editorial copy in the autumn of 1914 to about 20 per cent in the autumn of 1916 (see Table 1.2). Approximately 60 per cent of the war coverage comprised telegram material, and throughout the war the official communiqués of the respective army leaders and governments reigned virtually supreme when it came to telegram material, something that Dagens Nyheter was quick to spot early on:

Where does the world press get the news from that it now dishes up, and that is repeated in one newspaper after another almost verbatim? It must now mainly be the task of the major telegram agencies to procure it, which in other words means that it is the respective army leaders—the general staff—that dispatch it, naturally well-laced with their own interests. So it is not ‘the newspapers that are lying’ when one telegram reports a defeat and the other reports a victory.32

So there was not very much independent journalism to be found in the newspapers; more a collage of telegrams that voiced the warring parties’ differing versions of events.33 Even though the percentage of editorial copy given over to the war decreased as the war became routine, it is worth noting that the share of illustrations in the coverage increased from 8 per cent in 1914 to 14 per cent in 1916 (see Table 1.3). At the same time, the nature of the illustrations also changed. While the illustrations in certain parts of the daily press in 1914 mainly comprised drawings from photographs, the illustrations in 1916 were almost exclusively direct reproductions of photographs. Seen with modern eyes, one can say that the war became visually more present—although it is far from certain that it was perceived as such at the time. The illustrations in the weekly magazines, meanwhile, mainly comprised photographs throughout the war.

Gerhard Paul, in his presentation of the universe of war pictures, points out that because of the technological advances, it was possible for the first time to freeze motion in a photograph, and that the down-to-earth reproduction of war’s industrial technologies of destruction was a new photographic motif. On the other hand, war photographs were also more conventional in a mode reminiscent of genre painting and the landscape pictures seen from a tourist angle, only now in a more ravaged version.34 Taking these ideas as my point of departure, I have undertaken a quantitative survey of the mediation of the war in the newspapers Politiken and Social-Demokraten for the space of one week in September 1914 and again in October 1916, and in the magazines Illustreret Tidende, Hver 8. Dag, and Illustreret Familie-Journal, October 1914 and 1916. In categorizing the survey data, I have distinguished between pictures that reproduce an action or the result of an action (for example, a bombed house) and therefore contain a narrative, situational element, and pictures that reproduce their motif in its objective nature in a broad sense (for example, a view of a town, portraits, or pictures of materiel). The categorization further involved a division into four recurring groups of motifs: urban pictures, landscapes, people (civil and military respectively), and materiel. In this way it has been possible to distinguish three main genres of pictures: the tableauesque picture, which at times also makes a strong appeal to the emotions, and is a narrative scene which includes actions or the result of actions for all groups of motifs; panoramic images of towns and landscapes as objects; (technically) documented images of materiel and individuals or groups of people as objects (discussed in the next section).

The number of illustrations dropped by half between 1914 and 1916. The news value of the war diminished as time passed. Comprehensive illustrative material must have circulated, however, for neither in 1914 nor in 1916 has it been confirmed more than once or twice that the same illustration was printed in several media. The strongest recurring motif in the war coverage in both 1914 and 1916 is scenes with soldiers.35 In 1914, these scenes are flanked by urban panoramas, which as far as the newspapers were concerned largely consisted of pre-war pictures of the towns where the action was taking place (for example Antwerp or Reims). Indeed, the Swedish weekly Hvar 8 dag actually claimed in a controversy in the autumn of 1914 that when it came to pictures of soldiers, the other weeklies were printing ‘lots of old pictures of manoeuvres’.36 Apart from the touristy prospect pictures, the magazine press also printed many pictures of the physical destruction that resulted from bombing. In 1916, the scenes of soldiers are flanked by numerous portraits of leading military figures as well as pictures of materiel, with the number of urban pictures decreasing once the fighting had moved on from the towns of Belgium and Northern France.

The many scenes with soldiers only depict actual hostilities to a very limited extent, and where they do it is in drawings that elaborate on the scene of battle in a detailed battle painting style. Because of the strict censorship, the photographers did not have direct access to the front, and so there was nothing like the modern war photographs of actual hostilities and the immediate war zone, only pictures of the life for the soldiers behind the front. However, overly idyllic, touristy, and heroic portrayals are absent from most of the pictures of the soldiers’ lives.37 On the basis of a comprehensive survey of the coverage of the war in the Swedish weekly press, Lina Sturfelt proposes four basic narratives of the war: fatalism, heroism, fun and idyll, and the death factory. This categorization can only with difficulty be transferred to the visual representation of the war, however, partly because fatalism and heroism are very little represented in the visual material, and partly because few pictures of the soldiers’ lives behind the front can automatically be categorized under fun and idyll (see below).

The pictures that were published in the Danish media mostly came from the presses of the Entente Powers (see Table 1.6), and this became even more marked as the war progressed. Yet the prioritizing of sources in the individual papers differed considerably. In 1914, Illustreret Tidende and Social-Demokraten, unlike the others, had almost twice as many illustrations with German motif angle than with an Entente motif angle,38 which to a certain extent blurs the overall predominance of the Entente motif angle. In 1916, Illustreret Tidende had fallen into line with the rest of the magazine press, while both Politiken and Social-Demokraten had a fairly equal spread of sources.

Picture genres – prospects, tableaux, and instructions

The picture genres used to mediate the war were an extension of the picture formats developed during the breakthrough of visual media culture in the latter half of the nineteenth century. As did xylographs and, later, photographs, key genres such as landscapes and urban prospects, scenic narrative pictures, and technical drawings contributed to the dimensioning and spread of a visual space of knowledge and experience.

Because of the historical genres embedded in the visual construction of the war by the daily and magazine press, it adhered to special appeal structures in the form of preferred outlooks (optics) from which the flow of pictures gave (most) meaning. The landscape and the urban prospect appeal to a tourist gaze, characterized by a predominantly aesthetic attitude to the visual space. The instructional drawing or the technical illustration, known from illustrations of nineteenth-century inventions, speaks to analytical dissection and documentation, for it is intended to serve as a form of visual manual. The aim of the instructional drawing and, in a broader sense, photographs of materiel, grouped soldiers, and general portraits is to convey knowledge about a given subject. Finally, there is the narrative genre painting as a framework for conveying evidence of war that contains a narrative subject: civilians with buckets in ruined houses, soldiers shooting at aircraft. This optic often seeks to elicit a strong emotional identification from the reader, and it therefore seems obvious to characterize it as a theatrical look—to emphasize a kinship between that visual tradition and the prevalent, melodramatic tendency of late nineteenth-century popular culture, especially the popular theatre, and the silent films of the early twentieth century.

TABLE 1.1 Motif groupings, picture genres, and predominant views

In the visual representation of the war by the media, it was particularly in the initial phase of hostilities, when Germany invaded neutral Belgium, that urban prospects flourished. In the daily press this mainly took the form of urban scenes from before the war of the localities where the fighting was taking place, while the magazine press had a more even distribution of urban pictures from before and after German bombardments. The panoramic optic of the urban prospects set up a sounding board for the visual mediation of the war, which via a tourist view holds up for inspection, in an aestheticized state, an entire world from before the war. The pictures are not in themselves violently dramatic, but because of constant repetition and the contrast with houses reduced to rubble by shelling, the before–now pictures published particularly in the magazine press help to place the destructiveness of war in stark relief.

FIGURE 3A: Prospects, instructions, and tableaux. The same urban prospect as a tourist postcard and a war ruin respectively. Hver 8. Dag, 22 October 1916. (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

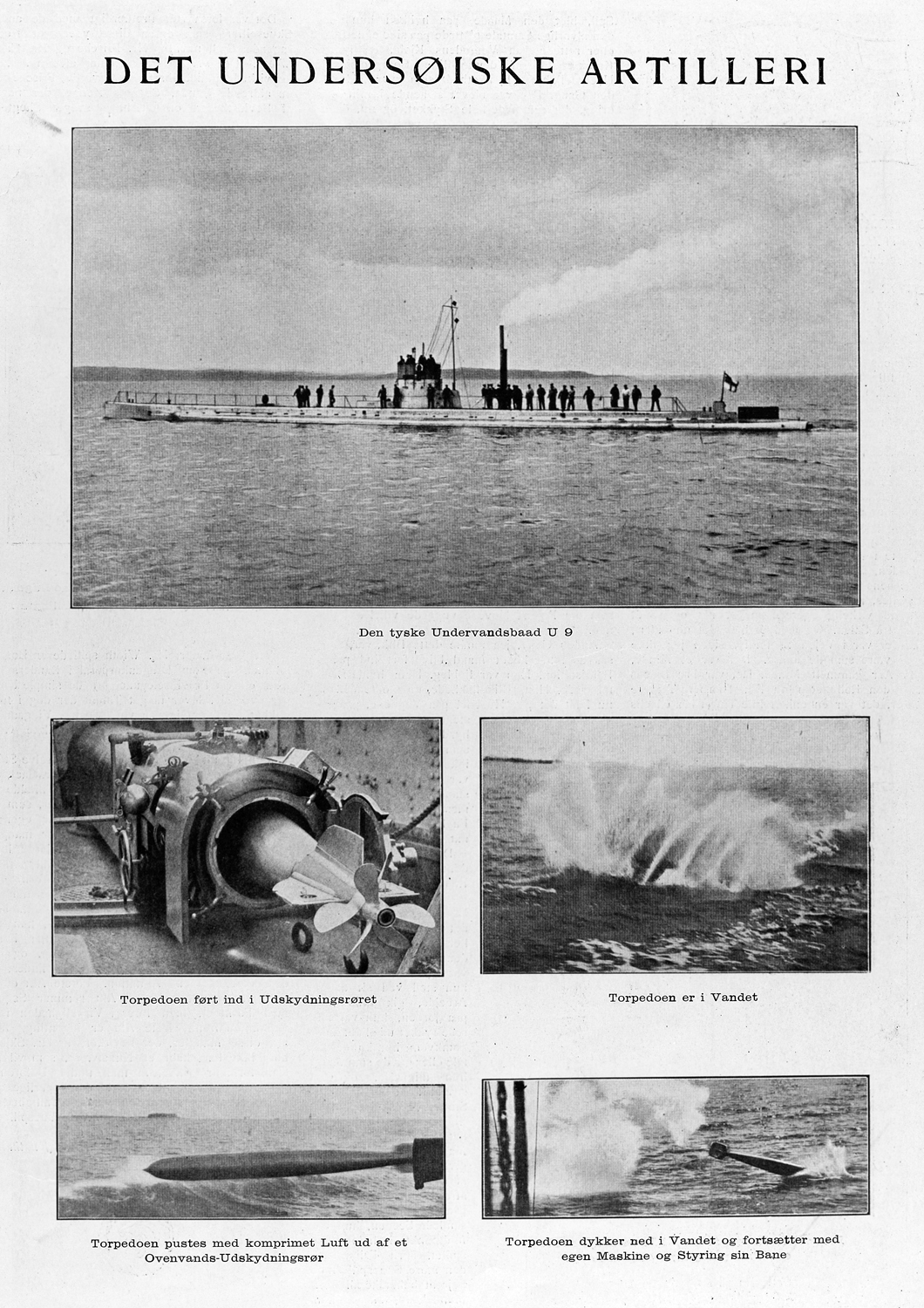

FIGURE 3B: Prospects, instructions, and tableaux. A visual orientation on how submarine torpedoes work. Illustreret Tidende, 4 October 1914. (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

FIGURE 3C: Prospects, instructions, and tableaux. Scenes of the war showing fleeing civilians and soldiers. Hver 8. Dag, 4 October 1914. (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

As a visual media phenomenon, the war to a great extent also comprised mute, massive materiel. Archive pictures of military materiel (cannons, ships) and pictures that show soldiers as objects en masse (typically marching) made up between a quarter and a third of the visual material. Images of materiel in particular tend to the technically instructive, which, combined with the explanatory captions, serves to impart knowledge about the war, documenting it within its technical, industrial framework. This documentation view can also be read from the way the pictures have an analytically dissecting function in conveying, for example, submarine torpedoes, where a picture of the submarine serves as a frame for a detailed visual explanation of the torpedo itself (see Figure 3).

The largest category throughout the war was pictures of soldiers in scenes with a narrative element, albeit one often restricted to a limited situation. Captions such as ‘The picture, which was taken at night, shows a British officers’ mess kitchen at work’, ‘From the Saloniki Front—Scots on guard’, ‘At a field post’, ‘Belgian ambush of a railway station’, and ‘German army bakery’ indicate that we are dealing with tableauesque motifs that are static and therefore easier to photograph, and that we seldom find ourselves at the front line. In Politiken, the difficulty of the situation was openly admitted: ‘Among the multitude of war pictures that the film companies, the major illustration agencies, and the illustrated magazines sent out into the world there are also pictures of clashes and battles, but these are always before or after. If there is a real battle, one can be sure that it will not be a photograph but a drawn picture.’39 In Pressens Magasin, readers were also openly warned against believing the photographs of battle scenes:

This picture has got past the Austrian censors. On the back it says that it was photographed during the Russian offensive on the Austrian Front. It admittedly shows some Russian soldiers in the middle of a barbed wire fence. But these are certain to be prisoners who have acted in a film for a plug of tobacco the Austrian photographer has promised them.40

Pictures of soldiers were not, however, entirely devoted to scenes of everyday routine or preparations for battle. Corresponding to the urban prospects of shattered houses, there were also pictures of wounded soldiers and men fallen in battle, and these emphasized the brutality of war. The tableauesque scenes with a narrative element were indebted in genre terms to the narrative painting (genre painting) of the nineteenth century, and naturally enough there were also strongly melodramatic illustrations—dead soldiers, dying horses—that most of all seem to be arranged photographs, or drawings based on genre paintings.41

FIGURE 4: Social-Demokraten, 14 October 1914, front page. (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

On the whole, the visual mediation of the war by the daily and magazine press helped to bring the war close in a neutral country such as Denmark; as to media history, the war pictures marked a turning point in the use of photographically reproduced illustrative material by the newspapers. The largely urban prospects filled in the background of pre-war life. On the basis of this, the period saw a developing, technical mediation of the war in all its material massiveness—the technology itself and the substantial volume of pictures of materiel and objectified soldiers en masse—as well as a narrative angling of the war with its focus on the soldiers. The narrative dimension spanned several scenarios: the destructiveness and brutality of war was emphasized in pictures of shattered towns and bodies on the battlefield; at the same time, scenes with soldiers were also used to give an impression of how mundane life at war became ‘mundanity’ in the shadow of the war. In my opinion, there was no real tendency to portray the war as an idyll in these war pictures, as is sometimes claimed—rather a visual insistence on the necessary routinization of everyday life at the front. We know very little about what people at the time made of this flood of war pictures, but there is at least one thought-provoking statement that points to the interaction of the various media, while indicating the both forbidden and titillating aspects of conjuring up fantasy images of war and then leafing through them, booklike, at leisure:

From time to time, among the hundreds of war accounts to which our eyes have gradually accustomed themselves, we suddenly stop at some episode or other that seizes us with dramatic force. Deep down inside us—as a thought of which we are almost ashamed—we feel a desire—without any form of risk involved—to be able actually to experience, to witness something similar. With all our dread and detestation of the war, we cannot even so … protect ourselves from having a certain audience-like urge to hold onto its images. And then the strange thing happens, that the next time we open an illustrated magazine or enter a cinema, we find precisely the ‘picture’ that we saw in our imagination when we read our newspaper.42

The First World War as visual culture

Seen from a point of view of the history of cultural and consciousness, the First World War is more than diplomatic negotiations and acts of war. It was also a mental horizon that supplied the material with which people thought their everyday lives. The visual representation of the war by the daily and magazine press was only part of a more extensive visualization of the war, translated into everyday life. Danish advertising in 1914 and 1916 is an example of this: in advertisements for everyday items such as Stomatol toothpaste, confirmation robes, and the ersatz coffee Kafa, military technology and uniforms have become natural points of reference. Not only that; one can find war motifs in several advertisements that include competitions for readers in the form of puzzles, mazes, and general knowledge quizzes.43 One can talk of the banalization and, in a longer perspective, the trivialization of the war experience.44

FIGURE 5A: The iconography of war as advertisement. Berlingske Tidende, 6 September 1916. (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

FIGURE 5B: The iconography of war as advertisement. Pressens Magasin, 1916/1). (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

FIGURE 5C: The iconography of war as advertisement.. Politiken, 24 October 1914 (Statens Avissamling, Statsbiblioteket Aarhus)

What further contributed to fixing the war as a visual phenomenon in people’s consciousness was the general release of silent films with war-related motifs. The Boer War was the first war of which there exist moving pictures, and by the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 there were examples of travelling companies in the Danish provinces showing films with motifs from the war.45 However, what we are dealing with here are scattered initiatives and a delay of at least half a year between filming and release. In the autumn of 1914, the situation was completely different. In October alone, five Copenhagen cinemas (Palads-Teatret, Biograf-Teatret, Metropolteatret, Kinografen, and Vesterbros Teater) advertised, extra-repertoire, ‘The latest war films’—early newsreels produced for propaganda purposes. One such advertisement indicates the piecemeal, episodic nature of the films, and, in this case, its German origin: ‘Latest war film: The Germans entering Brussels—Tired troops taking a break—The losses are counted. Red Cross wagons to transport the wounded—The Germans’ first action in Brussels’.46 There must have been a number of films in circulation, for apart from the wide range of cinemas offering them, there was also a relatively rapid turnover of films.47 At Palads-Teatret, for example, the war film repertoire changed four times during October 1914, prefiguring the twenty-four hour news cycle favoured today. The advertisements also emphasized the authenticity and topicality of the news reports: ‘Unique Express News Item’.48 Alongside the cinemas, the round Panoptikon building for three-dimensional panorama shows in Copenhagen was also able to supply war experiences in the form of ‘The great war panorama. A night in the trenches’. The First World War was thus a telling presence in media culture, stretching far beyond the photographs and drawings mediated by the daily and magazine press; a media culture that not only constructed the image of the war, but also contributed to making it part of everyday life.

TABLE 1.2 One week’s war coverage in three Odense papers and Politiken in 1914 and 1916

Survey periods: 7–13 September 1914 and 2–8 October 1916.

TABLE 1.3 One week’s war coverage in Politiken in 1914 and 1916

Survey periods: 7–13 September 1914 and 2–8 October 1916. War coverage 1914: 64,680 colmm. War coverage 1916: 23,660 colmm.

TABLE 1.4 Motifs used in Politiken’s and Social-Demokraten’s visual mediation of the war

TABLE 1.5 Motifs in the magazines’ visual mediation

TABLE 1.6 Motif angles in newspapers and magazines

Notes

1 ‘The Press and War’, Journalisten (1918), 2–3, 16.

2 Karl Erik Gustafsson & Per Rydén (eds.), Den svenska pressens historia, iii (Stockholm: Ekerlids Förlag, 2001), 146.

3 Tor Are Johansen, ‘Illustrasjoner i dagspressen’, in Hans Fredrik Dahl et al. (eds.), Norsk presses historie, ii (Oslo 2010), 138.

4 Tim N. Gidal, Modern Photojournalism. Origin and Evolution, 1910–1933 (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 6–8, 15–19.

5 For the comprehensive account of the transition to photography and film, see Gerhard Paul, Bilder der Krieges. Krieg der Bilder. Die Visualisierung des modernen Krieges (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2004).

6 Paul Virilio, War and Cinema (London: Verso, 1989), 70; see also John Taylor, War Photography. Realism in the British Press (London: Routledge, 1991), 20–3.

7 Paul 2004, 106, ‘Die Anwesenheit von Fotografen und Kameramännern veränderte die Situation auf den Schlachtfeldern. Soldaten begannen nun massenhaft für die Fotografen zu posieren und an Schaukämpfen vor den Kameras teilzunehmen. Ansätze einer spezifischen Repräsentationsästhetik des Krieges bildeten sich heraus, in der die Realität des Kampfgeschehens auf ihre mediale Vermittlung hin inszeniert wurde.’

8 Alain Sayag, ‘“Wir sagten Adieu einer ganzen Epoche”. Französische Kriegsphotographie’, in Rainer Rother (ed.), Die Letzten Tage der Menschheit (Deutsches Historisches Museum; Berlin: Ars Nicolai, 1994), 188, ‘Wahrnehmungsmechanisme’.

9 Paul 2004, 108; cf. Frank Hischer, ‘Der Erste Weltkrieg. Langzeitwirkung des ersten Bilderkrieges’, in Claudia Gunz & Thomas F. Schneider (eds.), Wahrheitsmaschinen (Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2010), 217–32, who sees the iconography in the photographs from the First World War as a prototype for later visual representations of war in the twentieth century.

10 Taylor 1991, 46.

11 Ibid. 42–46.

12 Gidal 1973, 11–12; Kenneth Kobré, Photojournalism (Oxford: Focal Press, 2008), 426.

13 Paul 2004, 123–4.

14 ‘Casellis Pantelegraph’, Illustreret Tidende 9/4 1865.

15 See the mention of ‘Professor Korn’s Picture Telegraphy’ in Politiken, 10 August 1908; see also Karl Erik Gustafsson & Per Rydén (eds.), Den svenska pressens historia, iii (Stockholm: Ekerlids Förlag, 2001), 110. Korn’s project and those of other picture telegraph pioneers is described in Gerhard Fuchs, Die Bildtelegraphie (Berlin: Verlag von Georg Siemens, 1926).

16 Elke Grittmann et al. (eds.), Global, lokal, digital – Fotojournalismus heute (Cologne: Herbert von Halem Verlag, 2008), 8–9.

17 Jürgen Wilke, ‘Nachrichtenagenturen als Bildanbieter’, in Grittmann et al. 2008, 62.

18 Gerry Beegan, The Mass Image. A Social History of Photomechanical Reproduction in Victorian London (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 2008, 163–6.

19 Thomas Hård af Segerstad, Dagspressens bildbruk. En funktionsanalys av bildutbudet i svenska dagstidningar 1900–1970 (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Ars Suetica 3; Uppsala: Textgruppen, 1974), 20; see also Stig Hjarvard, ‘“Det nyetste Nyt i Tekst og Billeder”. Om fotografiets rolle i skabelsen af den moderne danske avis 1900–1940’, Sekvens, 97 (1997), 155–85, which notes the co-existence of drawings and photographs in the 1910s. However, neither Segerstad nor Hjarvard deal with the special technological problems involved in printing photographs in newspapers.

20 Politiken established its own reproduction unit in 1912, which made photocopying, stereotyping, and electrotyping possible at the newspaper house, while Berlingske Tidende acquired its own stereotyping and elecrotyping unit as late as 1923. Generally speaking, the Scandinavian presses began to set up in-house units in around 1910 (Are Johansen 2010, 131, 137; Gustafsson & Rydén 2001, 110). The use of drawings based on photographs was not limited to wartime as far as Politiken was concerned. In the years leading up to the war there were many drawings that, just like the war drawings based on photographs, were marked with an ‘A’, referring to one of the newspaper’s five illustrators (three of whom used the initial A: Axel Nygaard, Valdemar Andersen, and Axel Andreasen).

21 Social-Demokraten, 5 October 1914 and 14 October 1914. According to Gustafsson & Rydén 2001, 110 it was normal practice to use drawings if plates or photography produced pictures that were too muddy.

22 In Norway, one of the major Oslo newspapers, Dagbladet, did not begin to use photographs until the early 1930s (Are Johansen 2010, 131).

23 Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion, (1922; New Brunswick: Transaction, 1998), 92.

24 This view is advanced by Lena Johannesson in her study of the xylographic press picture (Johannesson, Xylografi och pressbild (Nordiska museets Handlingar, 97; Uppsala: Almquist & Wiksell, 1982, 298).

25 In Sweden, the telegraph station in Stockholm was described as ‘a kind of telegraphic centre of Europe that came to function as a mediator of traffic between countries that no longer had any direct connections’ (K.V. Tahvanainen, Telegrafboken – Den elektriska telegrafen i Sverige 1853–1996 (Stockholm: Telemuseum, 1997). In Denmark, the telegraph station in Fredericia is now recognized to have been the communication hub: ‘Fredericia developed into Denmark’s most important telegraph station. It served both the Danish state lines and the foreign lines of Store Nordiske Telegraf Selskab. Here most of the internal telegrams and telegrams in transit through Denmark were dealt with. [...] Danish neutrality meant that the allies—France, Britain, Russia—could communicate via Fredericia without the Germany enemy being able to listen in as well.’ (Post&Tele Museum, Copenhagen, <http://mini.ptt-museum.dk/150aar/popup.html>, accessed 24 September 2012). At the time, however, it was Copenhagen that was considered to be the hub of telegraphic communication: ‘Copenhagen is fortunate enough to have connections with Berlin, Hamburg, Britain, Stockholm and Kristiania, and via Fredericia receives the British and Russian traffic’ (Hver 8. Dag, 13 September 1914).

26 Poul Thestrup, P&Ts historie 1850–1927, iii: Vogn og tog – prik og streg (Copenhagen: Generaldirektoratet for Post- og Telegrafvæsenet, 1992), 339.

27 Torsten Gihl, ‘Den svenska opinionen under världskriget. Aktivismen’, in Nils Ahnlund et al. (eds.), Den svenska utrikespolitikens historia, iv (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1951), 93–119; Svenbjörn Kilander, Censur och propaganda (diss.; Uppsala: Uppsala universitet, 1981).

28 Frejlif Olsen (1868–1936), editor of Ekstra Bladet, stood out as early as August 1914 as a result of strongly critical articles about Germany and the Danish army. Although several MPs wished to have Olsen dismissed, no action was taken because of his close connections with powerful people in the Danish press and politics (see Gregers Dirckinck-Holmfeld, Tør – hvor andre tier, i (Copenhagen: Ekstra Bladets Forlag, 2003), 67–73).

29 Stig Hadenius, Dagens Nyheters historia. Tidningen och makten 1864–2000 (Stockholm: Bokförlaget DN, 2002), 120, my translation.

30 Taylor 1991 (above, n. 5), 44.

31 Hadenius 2002, 125.

32 Dagens Nyheter, 9 August 1914, quoted in Hadenius 2002, 126.

33 This type of newspaper coverage was part of the special organization of the temporal and spatial relationships that, according to Anthony Giddens, characterizes modernity. Indeed, it is in connection with the emergence and use of the telegraph in journalism—in the form of news telegrams and up-to-date reports—that Giddens writes of the contraction of space because of ‘the intrusion of distant events into everyday consciousness’ (Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991), 27), to which the newspapers’ war coverage made a massive contribution.

34 Paul 2004 (above, n. 4), 117.

35 The absolute figures and percentages are listed in Tables 1.4–1.6. I do not give the percentage divisions, as the material, especially for the daily press in 1916, is extremely limited.

36 Gustafsson & Rydén 2001, 110.

37 See Paul 2004, 118–9; Lina Sturfelt, Eldens återsken. Första världskriget i svensk föreställningsvärld (Lund: Sekel, 2008).

38 Motif angle indicates the angle from which a given motif is viewed, and is thereby also an indicator of where the picture in question comes from. Since none of the media studied here indicated their picture sources systematically, this is the only method of getting an approximate value for the origin of the picture flow. Listed picture sources are (German) ‘Frankl., Berlin’, ‘Berlin.Ill.G.’, ‘Ill. Zeitung’ ‘Boedeker, Berlin’, ‘Braemer, Berlin’, and Leipz.P.B.’; (French) ‘Branger, Paris’, ‘Meurisse, Paris’, ‘Chusseau Flaviens, Paris’, ‘Meurisse, Paris’, and ‘Trampus, Paris’; (British) ‘Ill.Bur., London’, ‘Record Press, London’, ‘Alifieri, London’, ‘Off.Phot., London’, and ‘Ill. London News’; and (Dutch) ‘Veren.Fotob., Amsterdam’. With regard to regulation of the flow of telegrams from the countries at war, Swedish studies show that the relationship between telegrams from the Entente Powers and the Central Powers was fairly balanced in the major morning papers, which meant that they lived up to the government’s recommendation (Hadenius 2002, 126–7).

39 Politiken, 8 October 1914.

40 Pressens Magasin, 1916:1, 87.

41 See for example, Illustreret Familie-Journal, 10 (1916), 16; ibid. 31 (1916), 9; and ibid. 34 (1916), front page).

42 Pressens Magasin 1917, 21, 22.

43 Illustreret Familie-Journal 1914, 47 & 50; Politiken, 24 October 1914.

44 See Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (London: SAGE; 1995; George L. Mosse, Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 126–56.

45 Kolding Avis, 10 February 1905.

46 Biograf-Teatret, Social-Demokraten, 4 October 1914.

47 Very limited sections of this film material are available at <http://www.dfi.dk/faktaomfilm/nationalfilmografien/nffilm.aspx?id=36907>, s.v. ‘War pictures’, where it is also possible to watch a twenty-five minute film. Accessed 24 September 2012.

48 Vesterbros Teater, Social-Demokraten, 26 October 1914. An enthusiastic contemporary mention of the possibility of using these films to experience aspects of the war is to be found in Julius Magnussen’s feature in Politiken, 1 October 1914, while Mosse 1991, 144–9 provides a description of various kinds of ‘entertaining’ presentations of the war in tableaux, theatre, and film.