Environment

THE LAND

WILDLIFE

NATIONAL PARKS

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

THE LAND

Measuring 1250km from east to west and between 31km and 193km from north to south, Cuba is the Caribbean’s largest island with a total land area of 110,860 sq km. Shaped like an alligator and situated just south of the Tropic of Cancer, the country is actually an archipelago made up of 4195 smaller islets and coral reefs, though the bulk of the territory is concentrated on the expansive Isla Grande and its 2200-sq-km smaller cousin, Isla de la Juventud.

Formed by a volatile mixture of volcanic activity, plate tectonics and erosion, the landscape of Cuba is a lush and varied concoction of caves, mountains, plains and mogotes (strange flat-topped hills). The highest point, Pico Turquino (1972m), is situated in the east among the lofty triangular peaks of the Sierra Maestra, while further west, in the no less majestic Sierra del Escambray, ruffled hilltops and gushing waterfalls straddle the borders of Cienfuegos, Villa Clara and Sancti Spíritus provinces. Rising like purple shadows in the far west, the 175km-long Cordillera de Guanguanico is a more diminutive range that includes the protected Sierra del Rosario reserve and the distinctive pincushion hills of the Valle de Viñales.

Lapped by the warm turquoise waters of the Caribbean Sea in the south, and the foamy, white chop of the Atlantic Ocean in the north, Cuba’s 5746km of coastline shelters more than 300 natural beaches and features one of the largest tracts of coral reef in the world. Home to more than 900 reported species of fish and more than 410 varieties of sponge and coral, the country’s unspoiled coastline is a marine wonderland that entices tourists from all over the globe.

The 7200m-deep Cayman Trench between Cuba and Jamaica forms the boundary of the North American and Caribbean plates. Tectonic movements have tilted the island over time, creating uplifted limestone cliffs along parts of the north coast and low mangrove swamps on the south. Over millions of years Cuba’s limestone bedrock has been eroded by underground rivers, creating interesting geological features including the ‘haystack’ hills of Viñales and more than 20,000 caves countrywide.

As a sprawling archipelago, Cuba boasts thousands of islands and keys (most uninhabited) in four major offshore groups: the Archipiélago de los Colorados, off northern Pinar del Río; the Archipiélago de Sabana-Camagüey (or Jardines del Rey), off northern Villa Clara and Ciego de Ávila; the Archipiélago de los Jardines de la Reina, off southern Ciego de Ávila; and the Archipiélago de los Canarreos, around Isla de la Juventud. Most visitors will experience one or more of these island idylls, as the majority of resorts, scuba diving and virgin beaches are found in these regions.

Being a narrow island, never measuring more than 200km north to south, means Cuba’s capacity for large lakes and rivers is severely limited (preventing hydroelectricity). Cuba’s longest river, the 343km-long Río Cauto that flows from the Sierra Maestra in a rough loop north of Bayamo, is only navigable by small boats for 80km. To compensate, 632 embalses (reservoirs) or presas (dams), larger than 5km altogether, have been created for irrigation and water supply; these supplement the almost unlimited groundwater held in Cuba’s limestone bedrock.

Lying in the Caribbean’s main hurricane region, Cuba has been hit by some blinders in recent years including three devastating storms in 2008, its worst year for more than a century (see boxed text,).

Return to beginning of chapter

WILDLIFE

Animals

While it isn’t exactly the Serengeti, Cuba has its fair share of indigenous fauna and animal lovers won’t be disappointed. Birds are probably the biggest drawcard (Click here) and Cuba boasts more than 350 different varieties, 70 of which are indigenous. Head to the mangroves of Ciénaga de Zapata near the Bahía de Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) or to the Península de Guanahacabibes in Pinar del Río for the best sightings of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it zunzuncito (bee hummingbird), the world’s smallest bird and, at 6.5cm, not much longer than a toothpick. These areas are also home to the tocororo (Cuban trogon; see boxed text,), Cuba’s national bird, which sports the red, white and blue colors of the Cuban flag. Other popular bird species include flamingos (by the thousand), cartacubas (a type of bird indigenous to Cuba), herons, spoonbills, parakeets and rarely-spotted Cuban pygmy owls.

Land mammals have been hunted almost to extinction with the largest indigenous survivor the friendly jutía (tree rat), a 4kg edible rodent that scavenges on isolated keys living in relative harmony with armies of inquisitive iguanas. Other odd species include the mariposa de cristal (Cuban clear-winged butterfly), one of only two clear-winged butterflies in the world; the rare manjuarí (Cuban alligator gar), an odd, ancient fish considered a living fossil; and the polimita, a unique land snail distinguished by its festive yellow, red and brown bands.

Reptiles are well represented in Cuba. Aside from crocodiles, iguanas and lizards, there are 15 species of snake, none of which is poisonous. Cuba’s largest snake is the majá, a constrictor related to the anaconda that grows up to 4m in length; it’s nocturnal and doesn’t usually mess with humans.

Cuba’s marine life makes up for what the island lacks in land fauna. The manatee, the world’s only herbivorous aquatic mammal, is found in the Bahía de Taco and the Península de Zapata, and whale sharks frequent the María la Gorda area at Cuba’s eastern tip from August to November. Four turtle species (leatherback, loggerhead, green and hawksbill) are found in Cuban waters and they nest annually in isolated keys or on the protected western beaches of the Guanahacabibes Peninsula.

ENDANGERED SPECIES

Due to habitat loss and persistent hunting by humans, many of Cuba’s animals and birds are listed as endangered species. These include the Cuban crocodile, a fearsome reptile that has the smallest habitat of any crocodile, existing only in the Zapata swamps and in the Lanier swamps on Isla de la Juventud. Other vulnerable species include the jutía, which was hunted mercilessly during the período especial (special period; Cuba’s new economic reality post-1991), when hungry Cubans tracked them for their meat (they still do – in fact, it is considered something of a delicacy); the tree boa, a native snake that lives in rapidly diminishing woodland areas; and the elusive carpintero real (ivory-billed woodpecker; see boxed text,), spotted after a 40-year gap in the Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt near Baracoa in the late 1980s, but not seen since.

The seriously endangered West Indian manatee, while protected from illegal hunting, continues to suffer from a variety of man-made threats, most notably from contact with boat propellers, suffocation caused by fishing nets and poisoning from residues pumped into rivers from sugar factories.

Cuba has an ambiguous attitude toward the hunting of turtles. Hawksbill turtles are protected under the law, though a clause allows for up to 500 of them to be captured per year in certain areas (Camagüey and Isla de la Juventud). Travelers will occasionally encounter tortuga (turtle) on the menu in places such as Baracoa. You are advised not to partake as these turtles may have been caught illegally.

Plants

Cuba is synonymous with the palm tree; through songs, symbols, landscapes and legends the two are inextricably linked. The national tree is the palma real (royal palm), and it’s central to the country’s coat of arms and the Cristal beer logo. It’s believed there are 20 million royal palms in Cuba and locals will tell you that wherever you stand on the island, you’ll always be within sight of one of them. Marching single file by the roadside or clumped on a hill, these majestic trees reach up to 40m in height and are easily identified by their lithesome trunk and green stalk at the top. There are also cocotero (coconut palm); palma barrigona (big-belly palm) with its characteristic bulge; and the extremely rare palma corcho (cork palm). The latter is a link with the Cretaceous period (between 65 and 135 million years ago) and is cherished as a living fossil. You can see examples of it on the grounds of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales Sandalio de Noda and La Ermita, both in Pinar del Río province. All told, there are 90 palm-tree types in Cuba.

Other important trees include mangroves, in particular the spiderlike mangroves that protect the Cuban shoreline from erosion and provide an important habitat for small fish and birds. Mangroves account for 26% of Cuban forests and cover almost 5% of the island’s coast; Cuba ranks ninth in the world in terms of mangrove density, and the most extensive swamps are situated in the Ciénaga de Zapata.

The largest native pine forests grow on Isla de la Juventud (the former Isle of Pines), in western Pinar del Río, in eastern Holguín (or more specifically the Sierra Cristal) and in central Guantánamo. These forests are especially susceptible to fire damage, and pine reforestation has been a particular headache for the island’s environmentalists.

Rainforests exist at higher altitudes – between approximately 500m and 1500m – in the Sierra del Escambray, Sierra Maestra and Macizo de Sagua-Baracoa mountains. Original rainforest species include ebony and mahogany, but today most reforestation is in eucalyptus, which is graceful and fragrant, but invasive.

Dotted liberally across the island, ferns, cacti and orchids contribute hundreds of species, many endemic, to Cuba’s cornucopia of plant life. For the best concentrations check out the botanical gardens in Santiago de Cuba for ferns and cacti and Pinar del Río for orchids. Most orchids bloom from November to January, and one of the best places to see them is in the Reserva Sierra del Rosario. The national flower is the graceful mariposa (butterfly jasmine); you’ll know it by its white floppy petals and strong perfume.

Medicinal plants are widespread in Cuba due largely to a chronic shortage of prescription medicines (banned under the US embargo). Pharmacies are well stocked with effective tinctures such as aloe (for cough and congestion) and a bee by-product called propólio, used for everything from stomach amoebas to respiratory infections. On the home front, every Cuban patio has a pot of orégano de la tierra (Cuban oregano) growing and if you start getting a cold you’ll be whipped up a wonder elixir made from the fat, flat leaves mixed with lime juice, honey and hot water.

Return to beginning of chapter

NATIONAL PARKS

In 1978 Cuba established the National Committee for the Protection and Conservation of Natural Resources and the Environment (Comarna). Attempting to reverse 400 years of deforestation and habitat destruction, the body set about designating green belts and initiated ambitious reforestation campaigns. It is estimated that at the time of Columbus’ arrival in 1492, 95% of Cuba was covered in virgin forest. By 1959 this area had been reduced to just 16%. The implementation of large-scale tree planting and the organization of large tracts of land into protected parks has seen this figure creep back up to 20%, but there is still a lot of work to be done.

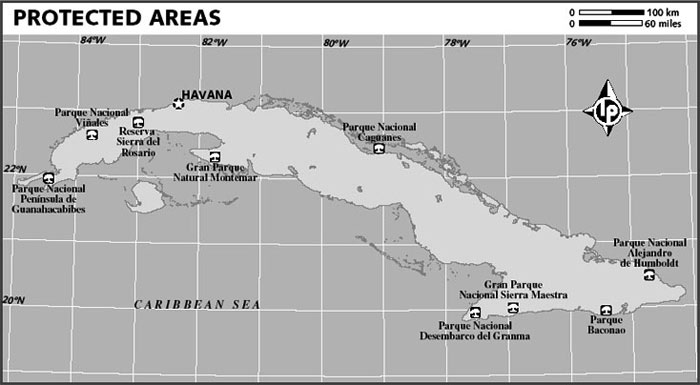

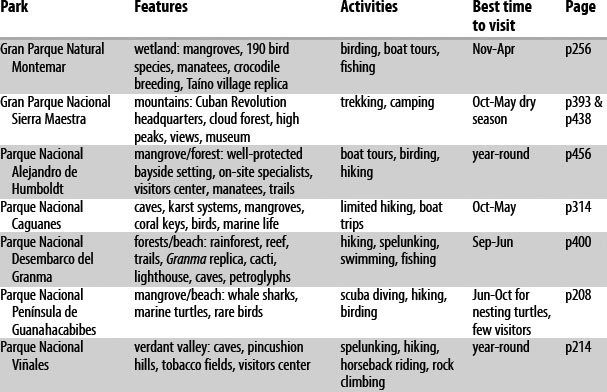

As of 2009, there were seven national parks in Cuba: Parque Nacional Península de Guanahacabibes and Parque Nacional Viñales (both in Pinar del Río); Gran Parque Natural Montemar (Matanzas); Gran Parque Nacional Sierra Maestra and Parque Nacional Desembarco del Granma (both in Granma province); Parque Nacional Alejandro de Humboldt (Guantánamo) and Parque Nacional Caguanes (Sancti Spíritus province). Of these, both Desembarco del Granma and Alejandro de Humboldt are also Unesco World Heritage Sites.

On top of these parks there are many more protected areas: natural parks, flora and fauna reserves, areas of managed resources, eco-parks, bio-parks and Ramsar Convention sites. The interconnecting network is often confusing (some parks have two interchangeable names) – and sometimes overlapping – but the sentiment’s the same; environmental stewardship with a solid governmental backing.

National conservation policies are directed by Comarna, which acts as a coordinating body, overseeing 15 ministries and ensuring that current national and international environmental legislation is being carried out efficiently and effectively. This includes adherence to the important international treaties that govern Cuba’s six Unesco Biosphere Reserves and nine Unesco World Heritage Sites.

Return to beginning of chapter

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

Cuba’s greatest environmental problems are aggravated by an economy struggling to survive. As the country pins its hopes on tourism to save the financial day, a schizophrenic environmental policy has evolved, cutting right to the heart of the dilemma: how can a developing nation provide for its people and maintain high (or at least minimal) ecological standards?

One disaster in this struggle, most experts agree, was the 2km-long stone pedraplén (causeway) constructed to link offshore Cayo Sabinal with mainland Camagüey. This massive project involved piling boulders in the sea and laying a road on top, which interrupted water currents and caused irreparable damage to bird and marine habitats. Other longer causeways were built connecting Los Jardines del Rey to Ciego de Ávila (27km long; Click here) and Cayo Santa María to Villa Clara (a 48km-long monster; Click here). The full extent of the ecological damage wreaked by these causeways won’t be known for another decade at least.

Building new roads and airports, package tourism that shuttles large groups of people into sensitive habitats and the frenzied construction of giant resorts on virgin beaches exacerbate the clash between human activity and environmental protection. The grossly shrunken extents of the Reserva Ecológica Varahicacos in Varadero due to encroaching resorts is just one example. Rounding up dolphins as entertainers has rankled activists as well. Overfishing (including turtles and lobster for tourist consumption), agricultural runoff, industrial pollution and inadequate sewage treatment have contributed to the decay of coral reefs, and diseases such as yellow band, black band and nuisance algae have begun to appear.

As soon as you arrive in Havana or Santiago de Cuba, you’ll realize that air pollution is a problem. Airborne particles, old cars belching black smoke and by-products from burning garbage are some of the culprits. Cement factories, sugar refineries and other heavy industry take their toll. The nickel mines engulfing Moa serve as stark examples of industrial concerns taking precedence: this is some of the prettiest landscape in Cuba, turned into a barren wasteland of lunar proportions.

On the bright side is the enthusiasm the government has shown for reforestation and protecting natural areas – there are several projects on the drawing board (see boxed text,) – and its willingness to confront mistakes from the past. Havana Harbor, once Latin America’s most polluted, has been undergoing a massive cleanup project, as has the Río Almendares, which cuts through the heart of the city. Both programs are beginning to show positive results. Sulfur emissions from oil wells near Varadero have been reduced and environmental regulations for developments are now enforced by the Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment. Fishing regulations, as local fisherman will tell you, have become increasingly strict. Striking the balance between Cuba’s immediate needs and the future of its environment is one of the Revolution’s increasingly pressing challenges.