Megaliths

From around 5000 BCE, massive stone structures were erected across the world. Intended to be seen from great distances, the majority of megaliths (from the ancient Greek megas meaning ‘great’, and lithos meaning ‘stone’) are believed to have been used for religious rituals. Some, mainly in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Saudi Arabia, probably related to farming.

The most famous and sophisticated surviving megalithic monument is Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England (opposite), built in phases from around 3000 to 2000 BCE. Set in a precise stone circle, the giant stones are positioned with astronomical precision to align with rising and setting points of the Sun at specific times of year. The massive horizontal stone lintels and vertical posts are attached using the mortice-and-tenon technique, with carved protrusions on the uprights that fit neatly into slots on the lintels.

Mesopotamia and Persia

Predating the earliest known Egyptian buildings, the first permanent structures in the Near East were built in the area known as Mesopotamia from the tenth millennium BCE. The first culture to thrive in this region (between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in present-day Iraq) were the Sumerians, followed by the Akkadians, the Assyrians, the Babylonians and finally the Persians, who conquered the area in 539 BCE. Among these civilizations’ many accomplishments – including agriculture, a written language and the wheel – was the development of urban planning.

Architecture does not seem to have existed as an occupation, but the Mesopotamians perceived ‘the craft of building’ as a divine gift taught by the gods. They were the first society to build entire cities, dominated by ziggurats – tombs built to resemble the mountains where the gods lived. Cities were walled for protection, with large gateways. Mesopotamian buildings were initially made of mud bricks, but later of bricks fired in ovens.

Sumerian ruins at Naffur, Iraq

Sumerian ziggurats

Ziggurats were stepped pyramids built for the worship of gods – at first by the Sumerians, but later by the Babylonians, Akkadians and Assyrians. Constructed in a stack of diminishing tiers on rectangular, oval or square bases, they had distinctive flat tops, and formed the focal point of Mesopotamian cities.

The oldest surviving ziggurat, in the ancient city of Uruk, pre-dates the Egyptian pyramids by several centuries. A shrine at the summit of the stepped platform was approached by outer stairs. The temple is believed to have been dedicated to the sky god Anu, and its corners point towards the cardinal points of the compass. Nearly a millennium later, during the Neo-Sumerian Empire, the ziggurat at Ur (opposite) was built c.2113–2096 BCE. The best preserved of the ancient ziggurats, it is built with a core of mud bricks and an outer casing of fired brick. Three converging ramps lead up to a platform, from which a central stairway continues to the top, where a temple once stood.

Egyptian pyramids

The pyramids were built as tombs for the rulers of Egypt’s Old and Middle Kingdoms between c.2600 and 1800 BCE. Three types were built: step, bent and straight-sided. The most imposing are those at Giza (opposite), the largest of which was built for the pharaoh Khufu.

The pyramid shape is believed to have been favoured for the great heights that could be achieved, the notion of pointing directly up to the gods, and the commanding presence they created across the surrounding flat valleys. In a practical sense, fewer stones were required to be hauled to the top. These massive constructions – some rise up to 146 metres (450ft) while some of the blocks of limestone weigh 15 tonnes – were built with the utmost precision; the casing stones are so finely joined that a knife’s edge cannot fit between them. Within, narrow passages lead to the royal burial chambers. Gypsum mortar held the blocks together, and the entire structures were encased in smooth white limestone quarried from the east bank of the River Nile, with the summit often topped in gold.

Ancient Egyptian temples

Built for the worship of gods, ancient Egyptian temples evolved from small shrines to large complexes. By the time of the New Kingdom (c.1550–1070 BCE), temples had become massive stone structures consisting of enclosed halls, open courts and entrance pylons. Certain parts could only be entered by priests, but the public visited other areas to pray, give offerings and seek guidance from the gods.

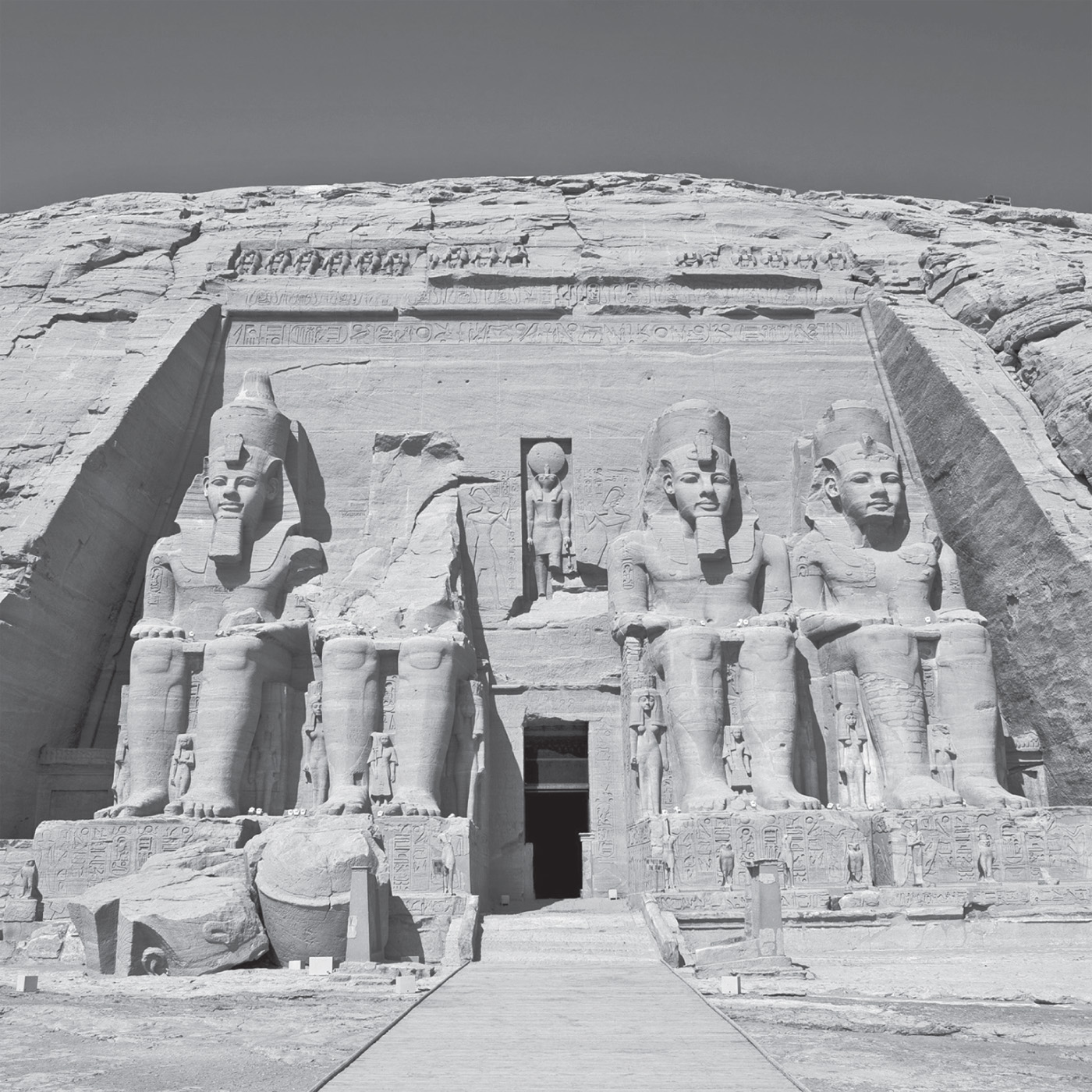

Notable examples include the Temple of Khons, built in 1198 BCE, with an avenue of sphinxes leading to an obelisk and hypostyle (columned) hall. Queen Hatshepsut’s temple, designed by the architect Senenmut, was a geometric edifice dug into a rock face, built in 323 BCE. Its extended, double-colonnaded terraces are on three levels connected by ramps. The two Abu Simbel temples are also massive rock-cut structures, commissioned by Rameses II as monuments for himself (opposite) and his queen Nefertari. The entire complex was relocated in 1968 to avoid being submerged in Lake Nasser.

Assyrian fortifications and temples

The Assyrians (c.2500–539 BCE) were a warlike people for whom city fortifications served both a defensive and an ideological role: massive walls, representing the king’s power, bore sculpted surfaces that displayed victories over enemies. The city of Nimrud boasted a palace set in vast courtyards, a ziggurat, the temple of Ezida and a huge encircling wall studded with towers. The final capital of the Assyrian Empire was the city of Nineveh (opposite), founded c.700 BCE on the Tigris River opposite the site of modern-day Mosul. King Sennacherib built a 12-kilometre (7.5-mile) brick wall around it with 15 towering gates, each named after an Assyrian god and each flanked by square towers with parapets and battlements.

Assyrians were a polytheistic people with a powerful priestly class. Their cities contained temples where their main gods were revered; as in Egyptian temples, gods were believed to live in sacred areas where only the priests could enter, and each god was represented by a specific statue in the temple.

Babylon

Built c.562 BCE, at its peak Babylon was by far the largest city of its time, with an area of at least 10 square kilometres (3.9 square miles). Set on the Euphrates River, its walls enclosed a densely packed area of shrines, temples, markets and houses, all grouped along grand avenues that were arranged in a grid. The city’s Etemenanki Ziggurat (605–562 BCE) is believed to have inspired the biblical Tower of Babel. Part of a religious complex in the centre of the city, it was probably covered in coloured glazed bricks. Seven tiers rose from a square foundation 90-metres (297-ft) on each side, with a temple to the god Marduk at the top.

King Nebuchadnezzar II rebuilt the ziggurat as part of his reconstruction of Babylon in the sixth century BCE. He also built the Hanging Gardens – one of the seven wonders of the ancient world – for his wife, Amytis. The Ishtar Gate (opposite) was the largest and most breathtaking of eight entrances to the city. Finished with blue glazed bricks, it was decorated with reliefs of dragons, lions and young bulls.

Palace of Knossos

Decorated with frescoes on its walls depicting sports and religious ceremonies, the Palace of Knossos (built c.1700–1400 BCE) on the Aegean island of Crete was the ceremonial and political centre of Minoan civilization and culture, abandoned c.1380–1100 BCE. The palace complex was two storeys high and built around a large, open, square courtyard, comprising a maze of workrooms, living spaces and storerooms.

Colonnaded rooms were used for ceremonial purposes, and were usually on the first floor. Within, great columns were made not of stone, but of cypress tree trunks turned upside down and mounted on simple stone bases before being painted red. Although the palace has been immortalized in Greek mythology as the site of the Labyrinth (home of the half-man, half-bull Minotaur), it was actually well ventilated and light, with cool, sunlit rooms offering magnificent views. Yet there was no cohesive design to the rambling, extended building complex, which was added to over centuries of use.

Teotihuacán

In the broad San Juan valley to the northeast of modern-day Mexico City, at over 2,000 metres (7,000 ft) above sea level, stand the remains of Teotihuacán, once the largest and most powerful city in the pre-Columbian Americas. Who founded it, and when, remains something of a mystery, but its zenith was c.150 BCE–750 CE; the Aztec culture that arose more than a thousand years later considered Teotihuacán a sacred site and used ideas from its architecture for their own structures.

Organized in a strict grid, Teotihuacán once covered an area of up to 36 square kilometres (14 square miles). At its heart is a long, straight central avenue that the Aztecs called the Avenue of the Dead because the mounds lining its sides looked like tombs. The city’s pyramids, incorporating ziggurat-style platforms, include the Pyramid of the Moon (c.250 CE) and Pyramid of the Sun (c.200 CE). The latter, standing over 61 metres (200 ft) high, was originally plastered and painted red, and chambers buried deep beneath it were possibly the site of ancient creation rituals.

Mayan

The influence of Teotihuacán (see here) reached the Mayan people in the tropical lowlands of what is now Guatemala. Their civilization reached its peak around the sixth century CE, with over 50 independent states and more stone cities than any other pre-Columbian culture. These included vast complexes of terraced temple-pyramids and palaces built around large plazas.

With a population of about 45,000, the city of Tikal featured great plazas with many stone temples built on platforms, including wide staircases and painted stucco façades. The largest of these was the Temple of the Inscriptions (built c.700–800 CE) – a massive stone rectangle with a steep staircase leading up nine levels. The tall, narrow Temple of the Giant Jaguar, built c.730, rises in nine steep tiers of finely carved stone. Roof combs, or cresteria, crowned many Mayan pyramids. At Uxmal, a Mayan city whose name translates as ‘thrice built’, the Palace of the Governors (opposite, c.900) is a trio of wide, low buildings connected by triangular stone arches.

Inca

At its peak from 1438 to 1532 CE, the vast Inca Empire stretched 4,000 kilometres (2,500 miles) from Peru to Chile and across to the Amazon rainforests. Incan accomplishments in civil engineering were outstanding, but because they did not write, their history remains obscure. Most of their ceremonial architecture was built to worship the sun god and his temporal representative, ‘Inca’. Elements of their buildings include wall reliefs, terracing, trapezoidal openings and masks. Chan Chan was the capital of the pre-Incan kingdom of Chimor, built c.1200–1470. With reservoirs and an irrigation system, it was arranged on nine quadrangles, within which hundreds of near-identical mud brick buildings were organized. At an altitude of 2,430 metres (7,970 ft) above sea level, the granite-walled city of Machu Picchu (opposite) was built in the mid-1400s from local materials. Terraces, containing courtyards, gardens and fields, are noted for their mortar-free masonry: though extraordinarily close-fitting, the loose stone blocks permitted slight movement, which helped them survive earthquakes.