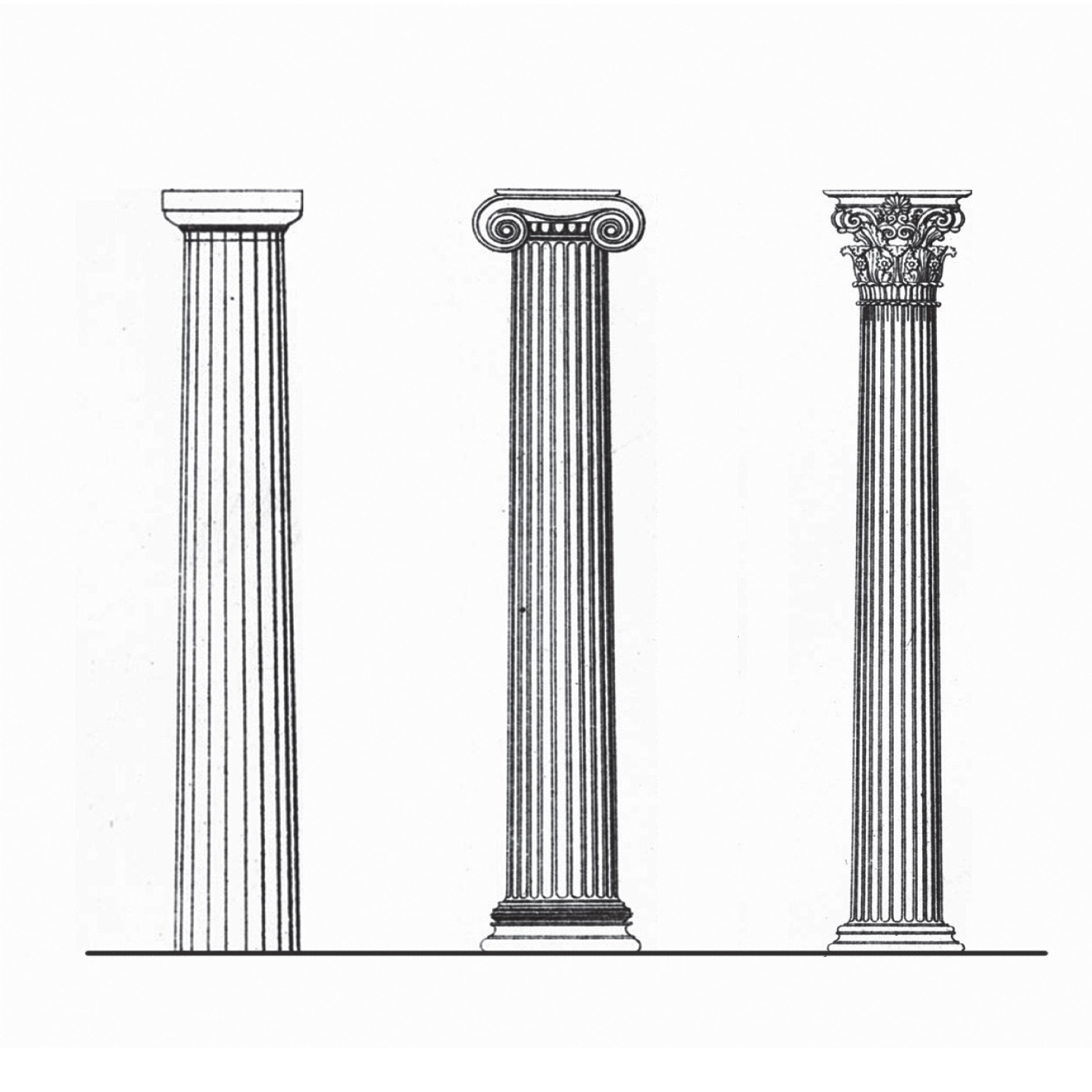

The Greek orders

By the fifth century BCE, Greek architecture had attained a purity of style, harmony and technical expertise. A century earlier, architects and stonemasons had developed a system of rules to use in all buildings. These rules became known as the orders, and are most easily seen in the styles of their columns.

A Greek column, normally comprising a capital, shaft and base, came in three types. The Doric, uniquely, has no base, and the fluted shaft rises up to a plain convex capital. Examples can be seen in the Parthenon. The Ionic is taller and slimmer, with flat bands separating the flutes on the shaft; there may be figurative reliefs around the base, and a female ‘caryatid’ figure may stand in place of a fluted shaft. Ionic capitals have two pairs of scroll-like volutes, with architraves that consist of three horizontal planes, each projecting slightly, and a plain or sculptured frieze. Similar to Ionic but more ornate, Corinthian capitals are often decorated with carved acanthus leaves and four scrolls, or sometimes with carved lotus or palm leaves.

Ancient Greek temples and theatres

Using a structural system of vertical columns and horizontal beams, the Greeks ensured architectural consistency and visual harmony. Their most important buildings were temples, closely followed by theatres, built on a range of scales.

The tiny temple of Athena Nike, built c.421 BCE to overlook Athens on one side and face the Acropolis on the other, has four Ionic columns to front and back, inspired by natural sources including rams’ horns, shells and Egyptian lotus flowers. In contrast the temple of Concordia (440–430 BCE) at Agrigento, Sicily (opposite), is a well-preserved example of the Doric order. The massive temple of Artemis at Ephesus (c.356 BCE), one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, was reached by steps flanked with bronze Amazonian warrior statues. Its central span of more than 80 metres (260 ft) was supported by almost 120 gold-coated Ionic columns. The theatre of Epidaurus (350 BCE) is an immense amphitheatre 118 metres (387 ft) across, with banked tiers of limestone seats and superb acoustic qualities.

The Acropolis

The temples on the Acropolis, a sacred rocky hill dedicated to Athena on the outskirts of Athens, represent the pinnacle of Greek architectural achievement. The hill had been inhabited as far back as the fifth millennium BCE, but Pericles (c.495–429 BCE) ordered and coordinated the construction of the site’s most important buildings, including the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion and the Temple of Athena Nike.

The sculptor Phidias (480–430 BCE) planned the layout for visual drama and spatial harmony, and most of the architecture was built in the Doric order, with slender columns and lavishly decorated friezes. A grand stairway leads to the marble columns of the Propylaea, a road for carts and sacrificial beasts, marking the entrance to the holiest area of the Acropolis. Behind the Propylaea stood a 9-metre (30-ft) bronze statue of Athena Promachus, while the elegant marble Temple of Erechtheion (c.420–393 BCE), built on a sloping site, has an entrance lined with six monumental caryatids (columns in the form of female figures), and two porches.

The Parthenon

Generally viewed as the archetypal Greek temple, the Parthenon (c.432 BCE) was designed by Ictinus, Callicrates and Phidias, and dedicated to the virgin (parthenos) goddess Athena, patron of Athens. Though it has some Ionic features, it is mainly Doric, with dimensions in the Doric length–breadth ratio of 9:4. Beneath its painted and gilded roof was a massive gold and ivory sculpture of Athena. While most Greek temples had six columns across the front, the Parthenon had eight. A total of 46 outer supporting columns of marble stood over 10 metres (33 ft) high; they are Doric, with simple capitals and fluted shafts, and the stylobate (column platform) is gently curved to shed rainwater and add strength. To compensate for the optical illusion of dead-straight columns appearing thin-waisted, the architects thickened them – a subtle distortion known as entasis. Above the architrave of the entablature was a frieze of 92 metopes (marble panels), while across the lintels of the inner columns runs a continuous frieze in low relief, comprising one of the Ionic elements of the building.

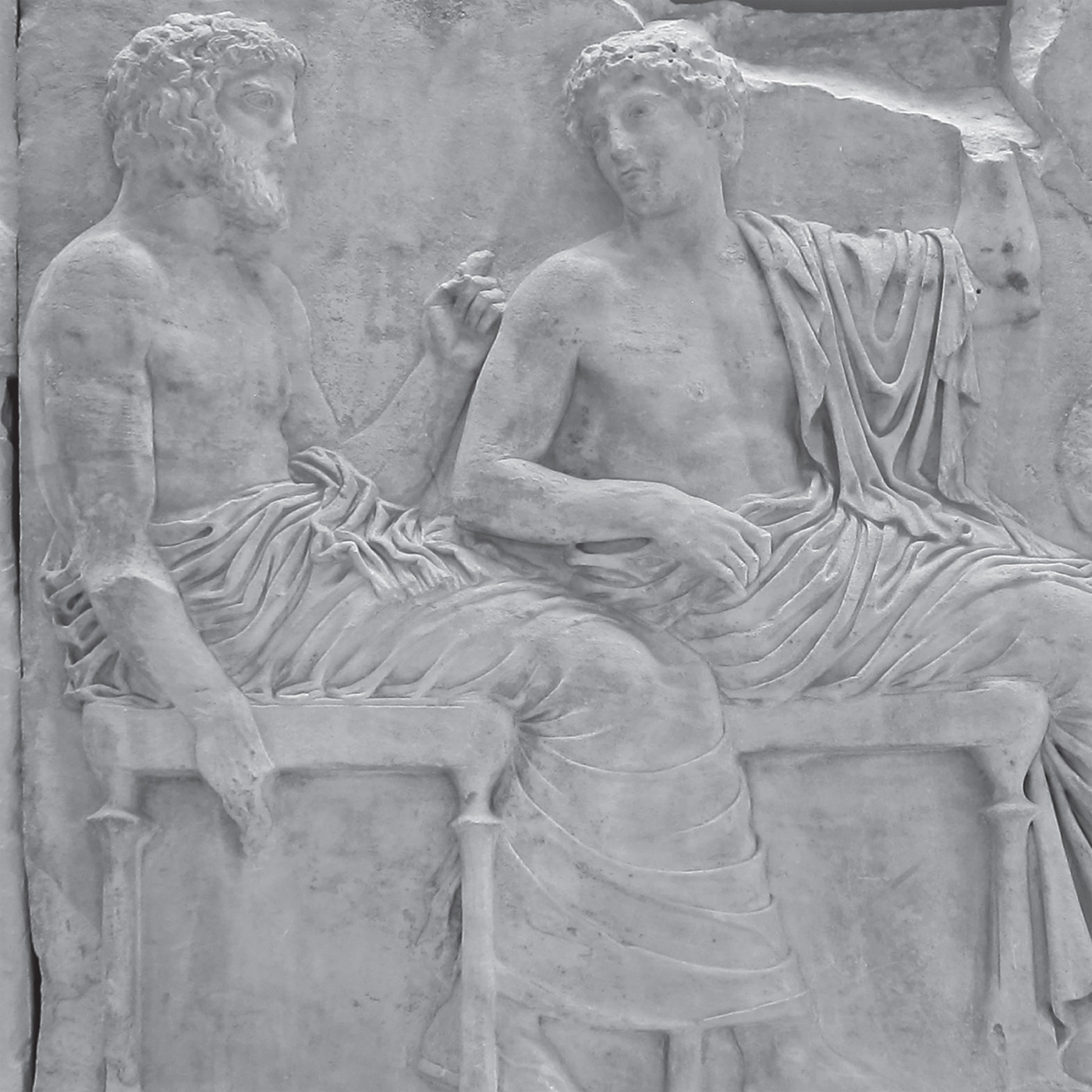

Greek architectural sculpture

Greek architects used a complex mix of optical illusions, ratios and rigid structural rules. The overall appearance of their buildings was intentionally simple, but sculptural decorations were often elaborate. Forming a key element of many temples and monuments, they featured on column capitals and pediments, in friezes and as statues.

Exterior sculpture usually featured in the metopes and triglyphs (two alternating panel types) of the entablature, the roof-supporting structure that sat across the columns. Some late Doric temples featured a continuous frieze around the outer wall of the cella (inner temple chamber), but the Ionic period, from the mid-sixth century BCE, brought more intricate decorations, including reliefs that often showed historicla or mythological narratives. Around the Parthenon’s cella, a low-relief frieze depicts the people of Athens in a Panathenaic procession, a key local celebration. Greek buildings and sculpture were always vividly painted, and often further embellished with metal accessories.

Greek urban planning

The first historical figure to be associated with urban planning was the architect, physician, mathematician, meteorologist and philosopher Hippodamus of Miletus (498–408 BCE). His plans for Greek cities were characterized by order and regularity, with straight, parallel streets laid out in rational grid systems, and functions grouped together in certain areas (something rare at the time, since any invaders would be able to find their way about by following this logic). Hippodamus planned the cities of Miletus (opposite), Priene and Lynthus, creating neatly ordered and organized cities with wide streets.

Shrines, theatres, government buildings, markets and the agora (a central space where athletic, political, artistic and spiritual activities took place) were all grouped together in central zones, and land use was divided into the sacred, public and private (mirroring Hippodamus’s division of the citizenry into three classes). Housing was the final area to be zoned, after all the other areas were allocated.

Stupas and temples

During the third century BCE, religious architecture developed in the Indian subcontinent with three types of structures: monasteries (viharas), shrines (stupas) and prayer halls (chaityas or chaitya grihas). Following changes in religious practice, stupas were gradually incorporated into prayer halls. These reached their zenith in the first millennium CE, particularly in the cave complexes of Ajanta and Ellora (see here).

Evolving from burial mounds, the stupa developed as a brick and plaster hemisphere with a pointed superstructure, often enshrining relics of the Buddha and acting as a sacred centre for rituals. The most famous surviving example is the Great Stupa at Sanchi from the first century BCE. These simple structures later evolved into complex Hindu temples, richly ornamented, often encrusted with sculpture, and sometimes also brightly painted. Noted examples are the temples of Angkor Wat (c.1100) in Cambodia (see here), and Phra Prang Sam Yod in Thailand (c.1300, opposite).

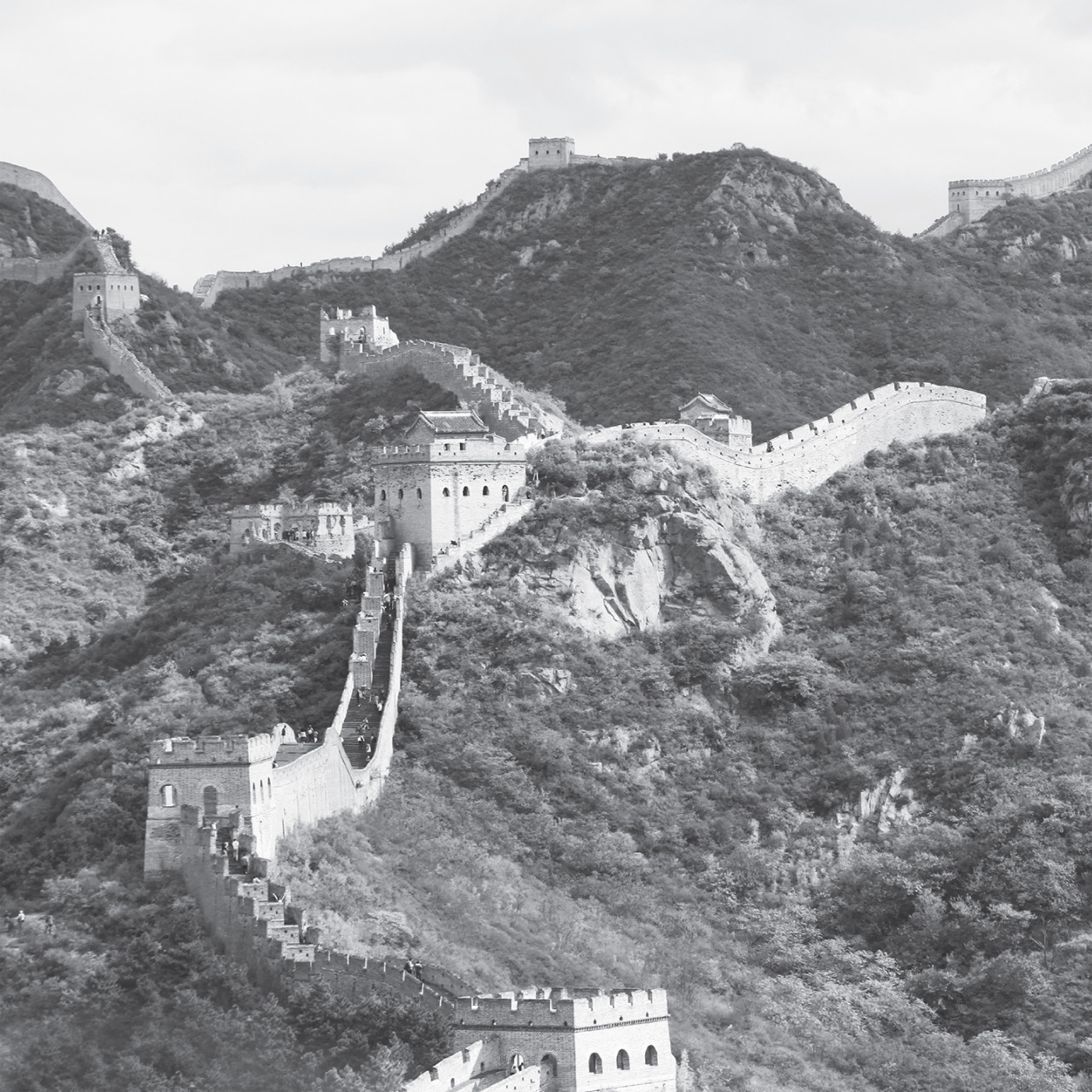

The Great Wall of China

The largest military structure in the world stretches some 6,500 kilometres (4,000 miles) from Shanhaiguan in the east to Jiayuguan in the west. The Great Wall is an amalgam of ancient walls from over 20 states and dynasties, first united into a single defensive system in 214 BCE under the rule of Emperor Qin Shi Huang (260–210 BCE), and later rebuilt three more times to protect against invasion. Varying in height from 6 to 10 metres (20 to 33 ft), the wall has an average depth of 6.5 metres (21 ft) at its base, tapered to 5.8 metres (19 ft) at the top.

Original local materials included stone, brick, rammed earth and wood, but the third rebuilding of the wall (from the ascent of the Ming dynasty in 1368 through to its conclusion in 1644) was stronger and more complex than any of the others. The eastern half is built of dressed stone or kiln-fired brick, the western half of rammed earth, sometimes faced with sun-dried brick. Watchtowers, gateways and forts along the length of the wall guarded against approaching raiders.

Pagodas

Tiered towers with multiple eaves, Chinese pagodas evolved from multi-storey timber towers created before the arrival of Buddhism in the first century CE, but share a heritage with Indian stupas. Primarily built of wood or brick, the structures themselves were hollow – their main function was to house religious relics beneath the ground, although a few were built in scenic isolation as elements of feng shui, and some began to appear on palaces as decorative features. Most early examples, built before the tenth century, had square bases, but later versions were built on polygonal plans. The shapes of the eaves and decorative details varied with time and location, while tiers changed from straight to an upwardly curving style dating from the 12th century. The earliest surviving Chinese timber pagoda is the White Horse Temple in Luoyang (founded 68 CE, rebuilt in the 13th century), while the oldest brick pagoda is the 12-sided Songyue monastery (523 CE, opposite). Buddhists introduced pagodas to Japan in the seventh century CE. They are highly resistant to earthquakes, owing to their structural flexibility.

Cave temples

Dating from the second century BCE to about 460–480 CE, some 30 rock-cut Buddhist cave temples were built at Ajanta, near the city of Aurangabad in the Indian state of Maharashtra. Nearby lie the Ellora caves (opposite), built during the sixth to ninth centuries by the Rashtrakuta dynasty and comprising Hindu, Buddhist and Jain temples. The Badami cave temples in the Bagalkot district, meanwhile, comprise four caves, all carved out of the soft sandstone cliff.

Today some 1,200 Indian cave temples survive, built chiefly between the fifth and tenth centuries, in fairly close proximity to each other. Relics from a period marked by religious harmony, most caves consist of viharas or monasteries: multi-storey buildings carved high up and deep inside mountains, comprising living quarters, kitchens, prayer halls and verandas. They feature complex construction methods, with integral pillars, intricate room systems and fine, detailed carving – not to mention the accurate removal of thousands of tonnes of rock.

Petra

Hidden from the outside world for hundreds of years, the Nabataean caravan city of Petra lay at an important crossroads on trading routes between Arabia, Egypt and Syria–Phoenicia. At the height of their power, the Nabataeans were a wealthy and powerful people controlling vast expanses of desert located in present-day Jordan. Tucked away between desert canyons and mountains, the capital of their empire was half-built, half-carved from rose-coloured sandstone between 400 BCE and 106 CE.

An ingenious water management system allowed Petra to thrive in an otherwise arid area: dwellings were simple, while civic and religious architecture was a blend of Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman influences. Façades blend simplicity and opulence with columns and carvings: the huge Khazreh or Treasury, tomb of King Aretas III (r.85–62 BCE), incorporates Corinthian and Nabataean columns (opposite), as well as friezes carved from solid rock, and figures from both Nabataean and Greek mythology.