Cement

Lacking the extensive quarries of marble available to the Greeks, the Romans had to create their own durable building material. The ancient Egyptians had used gypsum plaster (though this was not particularly strong), the Mesopotamians used bitumen, and some Greek builders, particularly on the coast of Turkey, had developed a form of cement around 200 BCE – but the Romans perfected it.

The Roman invention was distinguished by the addition of lime, which binds sand, water and clay, and by increasing use of finely ground volcanic lava (from Pozzuoli, near Naples) in place of clay. The resulting ‘pozzolanic’ cement was the strongest mortar in use prior to the British development of Portland cement in the mid-18th century. Roman concrete was based on a hydraulic-setting cement, which set and became adhesive due to a chemical reaction between its dry ingredients and water. By adding fragments of volcanic rubble to this mixture, the Romans were able to build their great feats of engineering.

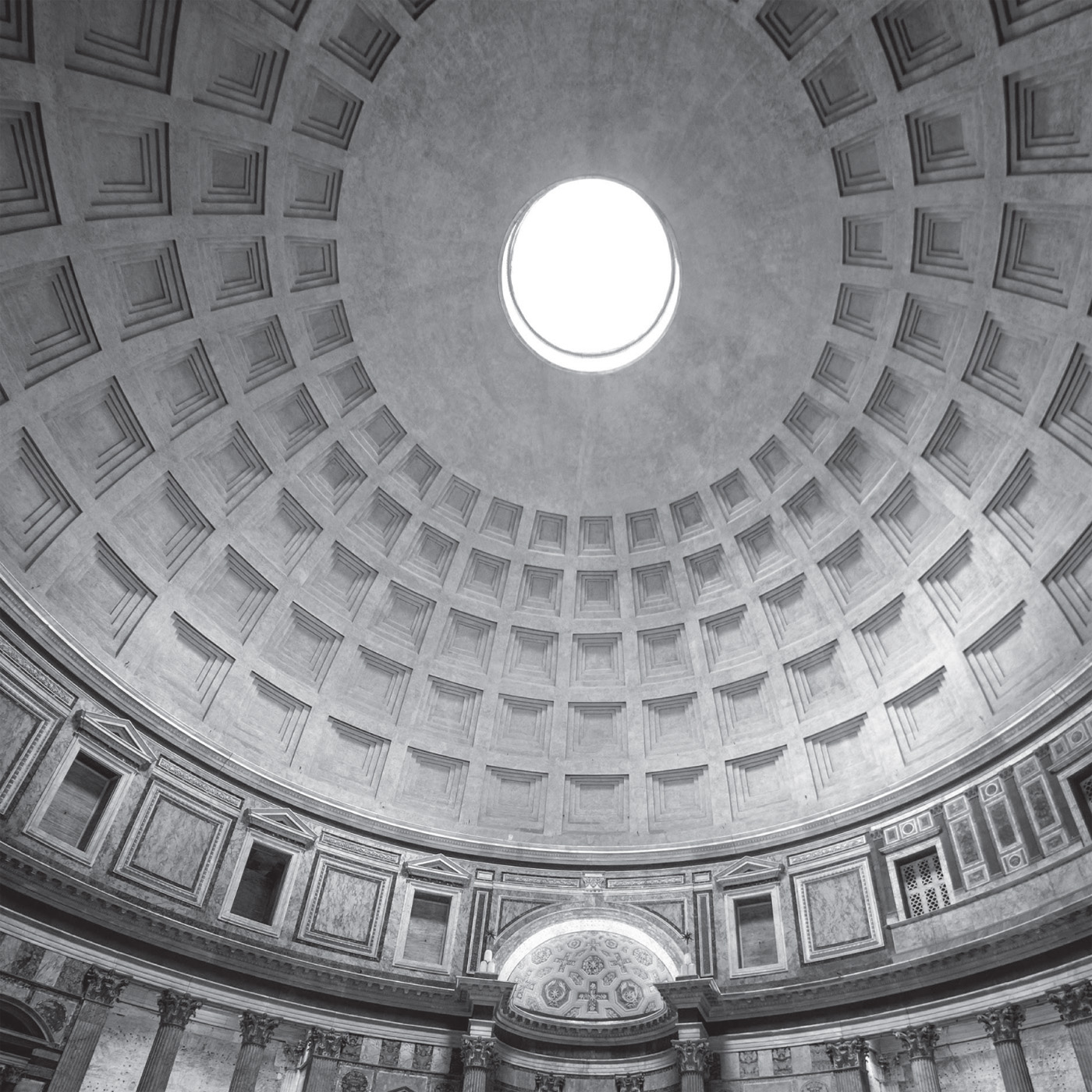

Concrete dome of the Pantheon, Rome

Vitruvius

Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (c.75–c.15 BCE) was a Roman architect, civil and military engineer who became known for his work De Architectura, or The Ten Books on Architecture. As the only surviving major work on architecture from classical antiquity, De Architectura is an important source of modern knowledge about Roman building methods, as well as planning and design. It had a huge influence on the artists and architects of the Renaissance, and for centuries influenced major buildings around the world.

Vitruvius asserted that a structure must exhibit the three qualities of firmitas, utilitas et venustas – firmness, commodity and delight. In other words, the ideal building is sturdy, useful and beautiful. Discussions on dimensions and ratios culminated in Vitruvius rationalizing the proportions of the human body. This ‘Vitruvian Man’ was later drawn by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) as a figure within a circle and a square, the fundamental geometric shapes of the cosmic order.

Roman engineering

The Romans built an empire that began with a few Italian states and spread to encompass most of Europe in the west, and to the Persian Empire in the east. They established their dominance in part through law-making, but also through developing advanced engineering techniques that enabled them to build straight roads irrespective of natural features, cities planned on rigid grids, aqueducts, viaducts, bridges, baths, arches and domes. Although some of their inventions and techniques simply improved on earlier (often Greek) ideas, their accomplishments surpassed any other civilization of the time.

Concrete made possible the construction of great vaults and domes, some of whose spans were not equalled until the development of steel in the 19th century. Amphitheatres allowed hundreds of spectators to see and hear spectacular displays, plays and special effects. Aqueducts, built from arches in one, two and three tiers, carried water in cement-lined channels, which ran along the upper level before diverting into pipes.

Roman aqueduct at Segovia, Spain

Arches, orders and inscriptions

Using free-standing columns as stabilizers, the Romans developed the rounded stone arch. Arches are often used to support large expanses of wall, and for building foundations. They are built upwards from either side using a temporary wooden frame, and the final stone to be dropped into the centre of a span is the keystone. From arches, the Romans also developed arcades (a series of arches on columns) and the barrel vault, cross vault and dome. They used five orders on their columns. To the Greek Doric, Ionic and Corinthian (see here), they added the Tuscan (an even simpler form of Doric) and the Composite, a richer form of Corinthian.

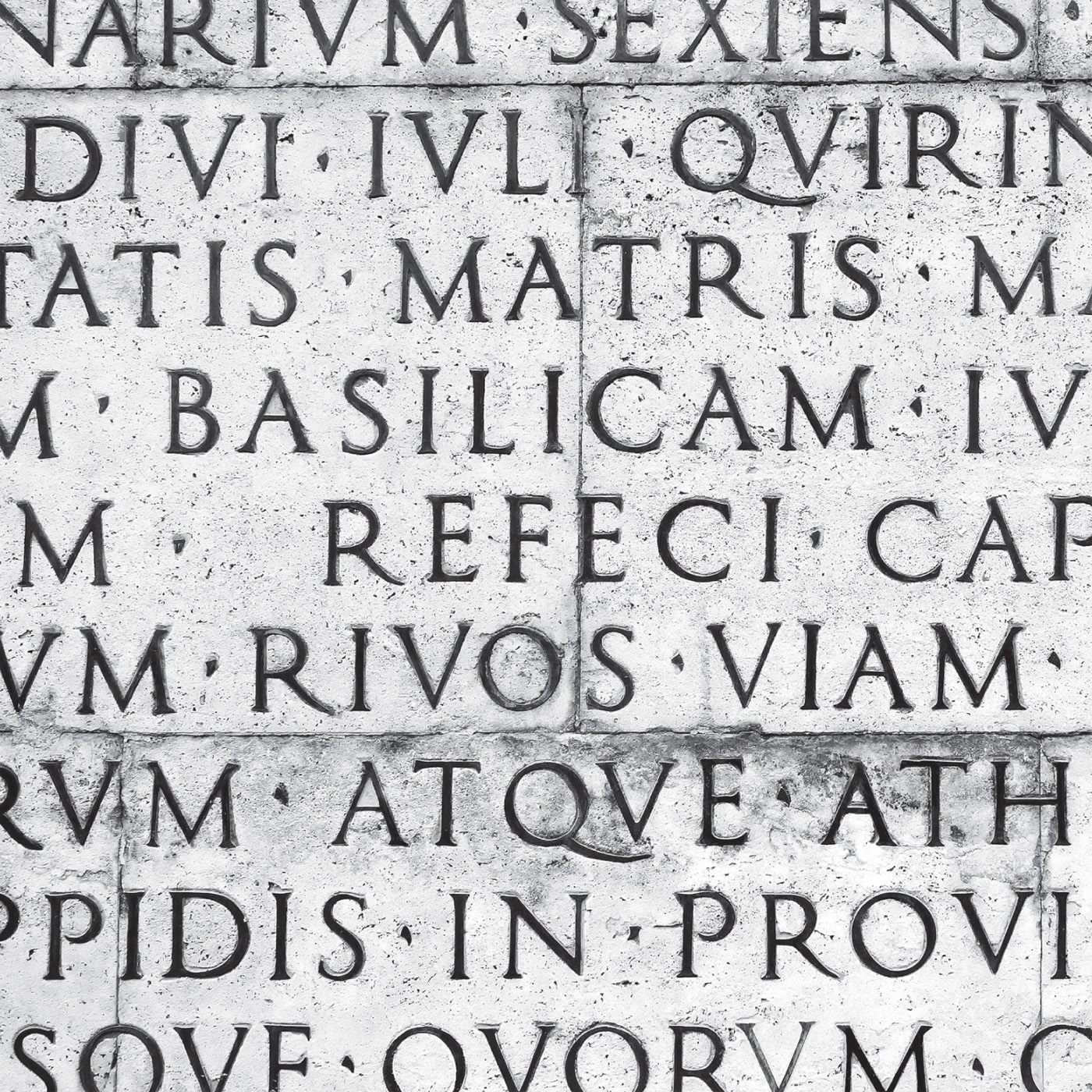

Columns and passageways were decorated with reliefs and free-standing sculptures. Some triumphal arches were surmounted by a statue or a currus triumphalis, a group of statues of the emperor or general. Inscriptions had finely cut letters, carefully designed for maximum clarity and simplicity, with no decorative flourishes, emphasizing a Roman taste for restraint.

The Pont du Gard

Crossing the River Gard in the South of France, the Pont du Gard is part of the Nîmes aqueduct, built c.40–50 CE to carry water from a spring at Uzès to the Roman city of Nemausus (Nîmes). General Marcus Agrippa, son-in-law and aide of Emperor Augustus, is credited with its conception. Although the direct distance between the two is only about 20 kilometres (12 miles), the aqueduct takes a winding route of about 50 kilometres (30 miles) to avoid the Garrigue hills above Nîmes. The tallest of all elevated Roman aqueducts, the Pont du Gard has three tiers of arches, and rises to a height of 48.8 metres (160 ft).

The first tier is composed of six arches, each 15–24 metres (51–80 ft) wide, with the largest spanning the river; the second tier has 11 arches of similar dimensions; while the third, carrying the conduit, consists of 35 smaller arches, each spanning 4.5 metres (15 ft). Like many ancient Roman structures, the Pont du Gard was built without mortar, and is a great example of the precision that Roman engineers were able to achieve.

Roman bridges

To create structures strong enough to span large distances, while bearing heavy loads and remaining stable, the Romans constructed voussoir arches with keystones. Voussoirs were wedge-shaped or tapered blocks of stone placed in semi-circular arrangements; to each side, the arch rested on piers or columns of stone blocks mortared with pozzolanic cement. The weight of the stone and concrete in the bridge itself compressed the tapered stones together, making the arch extremely strong. Voussoir arches were the basis for both single-span bridges and lengthy multi-arched aqueducts. Some early Roman arch bridges, influenced by the ancient notion of the ideal form of the circle, are made from a full circle, with the stone arch continuing underground. However, once engineers realised that an arch did not even have to be semicircular to remain stable, some later structures featured ‘segmental’ arches encompassing only a smaller arc of the circle. The Romans were also the first – and, until the Industrial Revolution, only – engineers to construct concrete bridges.

Roman bridge at Giornico, Switzerland

Roman temples

Based on Greek and Etruscan forerunners, Roman temples generally centred on a main room, or cella, housing the icon of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated (and often a small altar for incense or libations). Behind this lay one or more rooms used by temple attendants for offerings. Public religious ceremonies occurred outside the temple building; unlike Greek temples, which looked the same from all aspects, each Roman temple had a columned portico along its front.

The most important temple in ancient Rome was the Temple of Jupiter (509 BCE), which stood on the Capitoline Hill surrounded by a precinct where assemblies met and statues and victory trophies were displayed. After the original wooden temple burned down, it was rebuilt using Greek marble columns and covered in gold and mosaic. The circular Temple of Vesta (c.100 BCE, opposite) is the oldest surviving marble building in Rome, with 20 Corinthian columns. Despite its name, it is believed to have been dedicated to Hercules Olivarius, patron god of olive oil merchants.

The Colosseum

The largest amphitheatre ever built was constructed in Rome in 72–80 CE, to host public spectacles including gladiator fights, wild animal hunts and public executions. The Colosseum was part of a wider construction programme begun by Emperor Vespasian to restore Rome’s glory prior to the recent civil war. Like nothing ever built, it dominated the city and became a symbol of Rome, its society and culture. Oval in shape, made from locally quarried travertine stone, brick, volcanic stone and pumice, it also featured concrete, then a recent invention. The Colosseum had four tiers, with 80 monumental open arcades on three of them, and statues in each. The first floor had Doric columns, the second Ionic, and the top floor featured Corinthian pilasters (column-like reliefs on walls) and small windows. On each tier, passages and corridors had vaulted concrete ceilings on limestone supports. At over 45 metres (150 ft) high and 545 metres (1,780 ft) in perimeter, the Colosseum held some 50,000 spectators, who could be evacuated in 15 minutes.

The Pantheon

Built by the Emperor Hadrian c.128 CE, the Pantheon covered a temple erected by the Emperor Augustus’s son-in-law, Marcus Agrippa, in 27 BCE. The exterior, fronted by a portico of granite Corinthian columns (eight wide, three deep), leads to a huge rotunda. The spectacular dome, a half-sphere of 44.3 metres (144 ft) in diameter, is exactly equal to its floor to summit height. The 8-metre (27-ft) oculus, or ‘open eye’, at its crown is the main source of light. In the dome, sunken panels, or coffers, create interest, but also serve to hollow out the concrete and reduce its load on the brick supporting wall. The use of low-density rock, such as pumice, in the upper parts of the dome also reduces weight. With a series of restraining arches, the wall features alternating, curved and squared recesses. Overall, it is an open, airy, unified space. Pantheon means ‘all the gods’, and in 609 it became the first temple to be consecrated as a Catholic church, renamed the Church of Santa Maria ad Martyres. The remains of many Christian martyrs were brought from the catacombs and buried beneath its floor.

Basilicas, secular and sacred

The Roman public hall or basilica is a rectangular building with side aisles behind rows of supporting columns. The oldest-known example was built in Pompeii in the second century BCE. Originally, the basilica was a hall of justice or commercial exchange; tribunals took place in the apse (a recess at one end), and offerings were made at the altar before business began. In 313 CE, Constantine recognized Christianity, and by 326 it had become the official religion of the Roman Empire. The three great churches founded by Constantine in Rome are all basilicas. Two of them, St Peter’s and St Paul’s, feature the transept, which crossed the nave near the altar end and gave more space for pilgrims or clergy. (It also turned the ground plan into the shape of a Christian cross.) Nave, aisles, transept and apse became common elements of rectangular Western churches. When Constantine moved the new capital of Rome to Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople, the empire stretched from Milan and Cologne to Syria, Greece and Egypt, building basilicas everywhere that reflected local ideas.

Ruins of the second-century Severan Basilica at Leptis Magna, a Roman city in modern Libya

Roman towns and cities

Wherever the Roman armies conquered, they established towns and cities, extending the empire and, with it, their architectural and engineering achievements. Local materials were used, but common elements prevailed, including straight roads, arched bridges and aqueducts. Roman towns were designed in grids, centring on the crossing of two main roads, one oriented north–south and the other east–west. Where they met, the main buildings and spaces were set up, including the basilica, forum, market, amphitheatre, baths and temple. Dwellings filled the straight streets leading off the main roads. There was also an army barracks in every town, protected by a fortified surrounding wall, while aqueducts provided clean water and a sewage disposal system removed waste. The most well known of these towns and cities are Rome itself, Pompeii and Herculaneum, although Pompeii did not conform to a Roman grid as it had to fit into mountainous terrain. Private houses were typically ‘inward-looking’, opening onto a central courtyard, though many Pompeiian houses also had balconies.

Roman ruins at Ostia Antica, Italy

Roman baths

Roman houses had water supplied via lead pipes, but as water supply was taxed, public baths, or thermae, evolved. These took on monumental proportions, with colonnades, arches and domes, statues and mosaics. Features included the apodyterium (changing rooms), palaestrae (exercise rooms), notatio (open-air swimming pool), laconica and sudatoria (heated dry and wet sweating-rooms), the caldarium, tepidarium and frigidarium (hot, warm and cool rooms), and chambers for massage and other treatments, toilets, libraries and a range of other facilities.

Early baths were heated by braziers, later using the hypocaust system, in which wood-burning furnaces sent warm air under a raised floor. The introduction of glass windows from the first century CE improved temperature control. Water was supplied by purpose-built aqueducts and regulated by huge internal reservoirs. Notable examples include the Baths of Caracalla and Diocletian in Rome (c.215 and c.305 CE respectively), and the complex in Bath in England (second century CE, opposite).

Library of Celsus

The Library of Celsus at Ephesus was named after the city’s former Roman governor, Gaius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, whose tomb lies beneath its ground floor. Completed c.117 CE, it was a repository of over 12,000 manuscript scrolls, stored in niches around the walls on three galleried floors. Double walls behind the scroll niches protected them from the extremes of temperature and humidity, and there was also an auditorium for lectures or presentations.

Corinthian-style columns front the ground floor, whose three entrances are echoed by three windows in the upper storey. By making the columns at the sides of the façade shorter than those at the centre, the architects created the illusion of a larger building. Above the door stood a statue of Athena, goddess of wisdom, while statues flanking the front entrances represent wisdom (Sophia), knowledge (Episteme), intelligence (Ennoia) and valour (Arete): the virtues of Celsus. Reliefs are carved on the façade, while the interior was paved with decorated marble.