IN HIS 80s, Otto Warburg occasionally did something that he would have once found unthinkable: he played hooky. When the weather was nice, Warburg would call on his young glassblower, Peter Ostendorf, to drive him to the nearby Havel River. For the rest of the afternoon, the two would sail peacefully in the slow-moving waters in Warburg’s Nordic Folkboat, Warburg lecturing his young employee on his favorite books or the history of the region during the Holy Roman Empire.

If still “married” to science in the 1960s, Warburg had made another important discovery: there was more to life than the laboratory. Warburg and Heiss befriended two elderly women in Dahlem and sometimes had flowers from their garden sent to them. In return, the women would share their tickets to the philharmonic. Always a dog lover, Warburg grew especially attached to his nearly 200-pound Great Dane, Norman, who could be seen traveling to and from the institute in the back of Warburg’s black Mercedes. In the evenings, Norman rested on a couch in Warburg’s bedroom, where he took his “nightcap”: a piece of Warburg’s best chocolate.1

Warburg remained very much himself. He hated it when people raced their sailboats and would purposefully steer into the middle of the river to disrupt them. Ostendorf, who generally remembers Warburg fondly, could do nothing but sit in Warburg’s boat, embarrassed. Warburg also purchased a new country home in the North German island of Sylt. He chose the location, he once explained, because “the district is the most thinly populated in the whole of Germany.” With few neighbors to agitate him, Warburg directed his ire at the noise from planes overhead.2

Less work for Warburg was still a lot of work. In the late 1960s, he continued to publish some 5 to 10 papers every year on photosynthesis and cancer. But for all his willful obliviousness to modernity, Warburg could sense that his own research was becoming outdated. In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick had studied Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray crystallography images of DNA and deciphered the structure of the molecule. Modern molecular biology was suddenly coming into focus. Genes are made of DNA molecules, which function like a code in the nucleus of a cell. This code is read by other molecules to create, or express, proteins. To study the inner workings of the cell without taking into account the new molecular biology came to seem absurd, like trying to make sense of a complicated computer program without knowing anything about coding.

Warburg was not at all pleased to find himself in this new scientific era. It didn’t help that Dahlem’s notorious Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics had quietly morphed into a modern genetics institute. But the problem ran deeper, all the way to the core of Warburg’s scientific being. In Warburg’s view, molecular biology’s new obsessions with genes was adding a layer of complication to every discussion and, in the process, obscuring fundamental observations. It was, Warburg said, “as though before one could say anything about the plague bacillus, one would first have to determine the sequence of the nucleic acids.”3

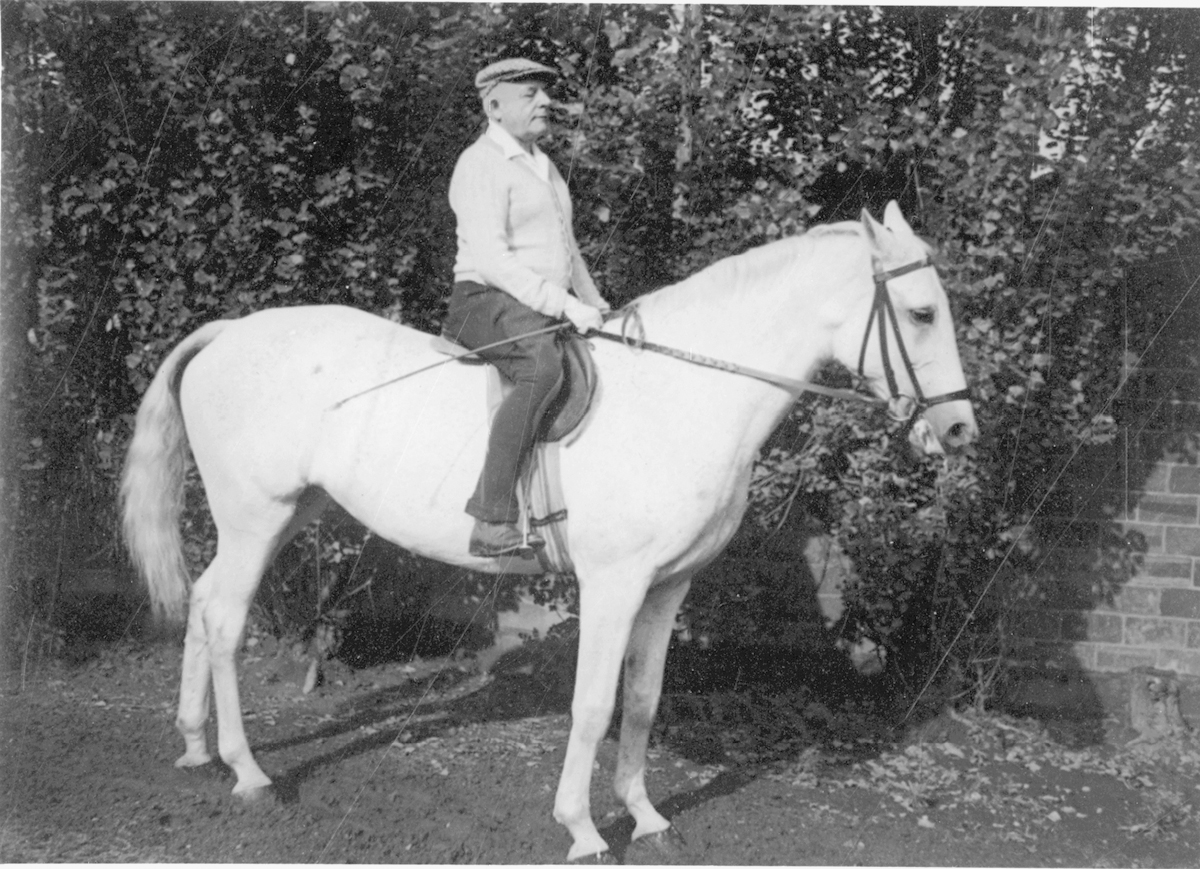

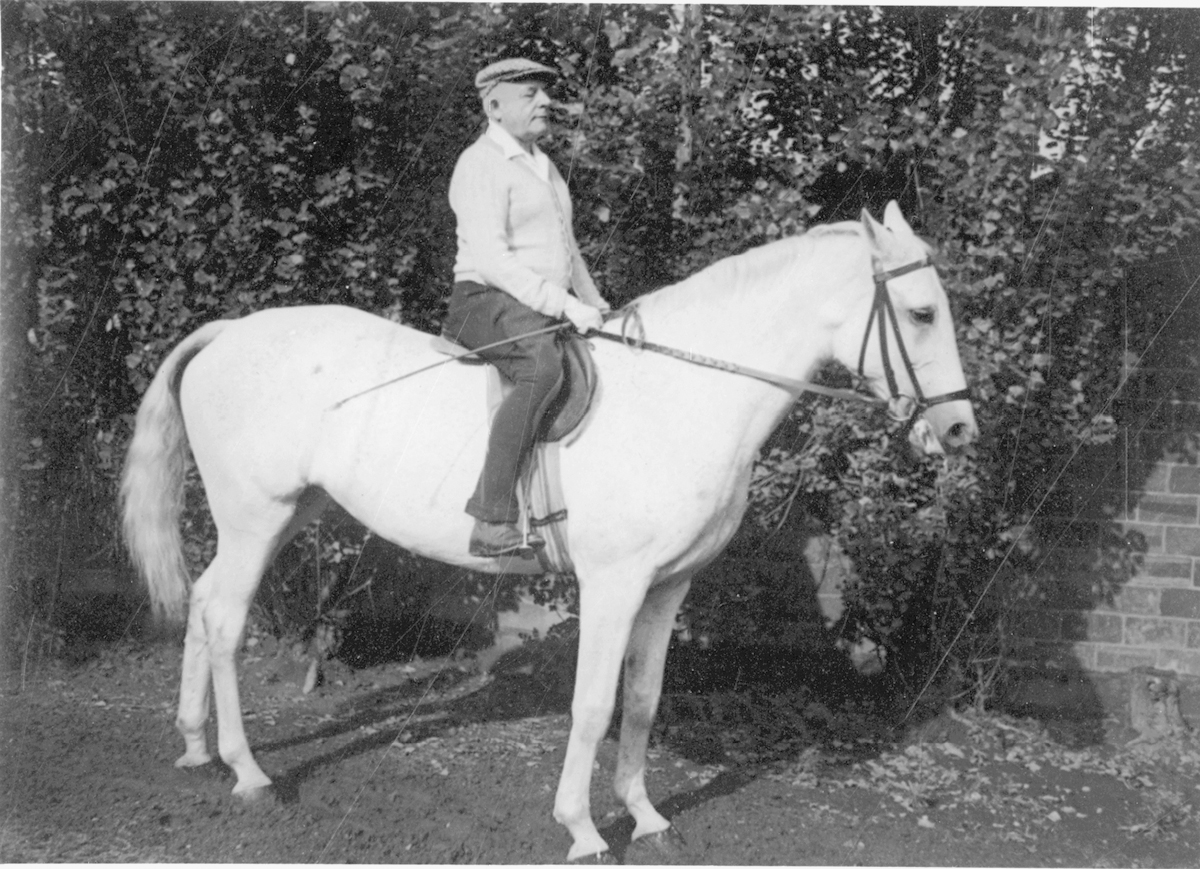

The German academic Wolfgang Lefèvre witnessed Warburg’s anachronistic existence in the late 1960s. At the time, Lefèvre was a student at the Free University of Berlin, the institution the Americans had built across the street from Warburg’s home in Dahlem after the war. He remembered that he and other students would sometimes stay up all night drinking and smoking while engaging in heated political discussions. When they finally stumbled out for fresh air, it would already be morning, and there, across the street, would be Otto Warburg atop his horse. Heiss would invariably be by the animal’s side, holding the reins as Warburg went round and round his property.4

In the spring of 1965, Dean Burk wrote a letter to Warburg describing how a colleague had taunted him at a recent conference: “Dean, why don’t you throw away your manometers and get down to some real biochemistry.” At approximately the same time, Peter Pedersen, a biochemist at Johns Hopkins, spotted a Warburg manometer left out in the hallway with the trash. The era of metabolism research was over. According to Pedersen—one of the few cancer researchers who would continue to pursue Warburg’s ideas about cancer and energy—there was “little or no interest” in Warburg’s cancer research by the late 1960s.5

As molecular biologists studying cancer turned their attention to DNA and cancer-causing genes, Warburg’s interest in how cells extract energy from food seemed not only outdated but backward. A 1972 article in the German magazine Der Spiegel claimed that Germany had fallen behind in the study of cancer DNA and viruses and that it was entirely Warburg’s fault. Warburg had “unilaterally” sent cancer research in the wrong direction, a biochemist at Frankfurt University told the magazine.6

If any trace of Warburg’s metabolic explanation of cancer still lingered, it would be gone by the middle of the next decade, after University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) researchers J. Michael Bishop and Harold Varmus identified the first cancer-causing gene. Such genes, known as oncogenes, had turned out to be normal human genes, only in mutated form. For the first time, Boveri’s initial hunch that chromosomes held the secrets to cancer could be explained in the language of modern science.

Otto Warburg, date unknown.

Two conceptions of cancer, one metabolic, one genetic, emerged from the study of sea urchins in the first decade of the twentieth century. The genetic conception had now prevailed. Warburg’s name was virtually erased from cancer science. In 1988, one biochemist was shocked to discover that young scientists of the day had not even heard of Warburg.7

The genetic explanation did not contradict the widely held belief that most cancer deaths were caused by our environments and potentially preventable. Smoking or toxic chemicals or diet could still be said to be “causes” of cancer. The emphasis on mutated genes merely offered a more precise way of explaining how environmental carcinogens inflicted their damage. But the new molecular biology might have undermined the broader push for cancer prevention just the same. Because mutations can arise by chance alone as dividing cells copy their DNA, any given cancer could now be dismissed as bad luck.

Prevention also felt less urgent in the new oncogene era. After Bishop and Varmus, a cure for cancer was thought to be only a matter of time. The gene they had identified, SRC, was one oncogene, but there were sure to be many others. To win the war on cancer, researchers would need only to identify these genes and learn how to turn them off. The magic bullets might still be missing, but cancer scientists had finally found their targets.8

EVEN AS MEMORIES OF Otto Warburg were fading, one scientist’s unlikely journey back to Warburg was already beginning. In the summer of 1985, nine years after Bishop and Varmus published their groundbreaking discovery, Chi Van Dang completed his medical residency at Johns Hopkins and decided to do his clinical fellowship in oncology at UCSF. Dang and his wife, Mary, crammed as much as possible—including their Persian cat—into their red Toyota Tercel and headed West, tracking their route, as best they could, on AAA maps.

The drive from Baltimore to San Francisco was only one more leg in Dang’s long journey. Dang, today the scientific director of the international Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, grew up in Vietnam in a family of 10 children. There was no TV in his home, but there was something to watch. After dinner, his father, the country’s first neurosurgeon, would often take out the 8-millimeter projector and show the children films of surgical techniques. With no better options for entertainment, Dang and his siblings sat and watched. “Some of it was pretty gruesome,” Dang recalled.9

In 1967, with the Vietnam War raging, Dang’s parents sent him and an older brother to live with an orthopedic surgeon in Flint, Michigan, who had met Dang’s father in Vietnam. Dang, 12 at the time, felt guilty about leaving his family behind in a war zone, but he adjusted to his new life well. Though he was sometimes harassed for being Asian, he was relieved that few of his new classmates in Flint realized he was Vietnamese.

Dang went on to the University of Michigan, where he studied chemistry. He never planned to become a cancer researcher, but like so many young people interested in medicine and science at the time, he wanted to be a part of the revolution in molecular biology. It felt like a “golden moment,” Dang recalled. And what better place to experience that moment than UCSF, home to Bishop and Varmus, the two researchers who had put the molecular biology revolution into motion.

The adjustment to San Francisco took some time. Dang would drive up the steep hills, only to find his Toyota, a stick shift, rolling back down whenever he tried to switch gears. It was a good reminder that a journey into cancer research can feel Sisyphean at times, yet Dang remained committed. Though he officially became stateless when South Vietnam ceased to exist in 1975, he could not have been more firmly rooted in medical science. Six of Dang’s nine siblings would also become doctors. Another became a dentist.

While learning to treat cancer patients, Dang got his chance to interview with Bishop and Varmus themselves for a postdoctoral research position. As he sat down for the meeting, it struck him that he still knew alarmingly little about the new world of molecular biology. When Varmus asked him what he wanted to work on, the most Dang could muster was “oncogenes.” Varmus nodded and asked him which particular cancer-related gene interested him most. Dang paused. It was a perfectly reasonable question, but one he couldn’t answer. Dang told the famous scientist the truth: he had no idea. “I barely knew anything,” Dang said much later.

Varmus pointed Dang toward UCSF researchers then working on MYC, one of a number of the newly discovered oncogenes. At the time, little was known about MYC other than that when overexpressed—meaning there were too many copies of its corresponding protein—it could drive cells to grow and multiply. As Dang and others began to study MYC, they saw that it isn’t merely one more signal in a chain. It codes for a type of protein, known as a transcription factor, that binds to the DNA, turning scores of other genes on and off and dramatically reshaping the behavior of the cell. Wherever Dang looked in the cancer cell, he seemed to find traces of MYC’s influence.

After his postdoc at UCSF, Dang returned to Johns Hopkins, still determined to identify the many genes under MYC’s sway. Lacking today’s modern sequencing tools, the search proved maddeningly slow. Work that would now take days could stretch on for months, even years. But Dang and the postdocs in his lab pushed ahead. Like cartographers tracing the contours of a newly discovered land, they mapped each chain of linked reactions, or signaling pathways, on diagrams that were reproduced and hung on the walls of cancer labs around the world. The diagrams were breathtakingly complicated. Dang and his generation of cancer biologists were not simply discovering a new land, but a land of interconnected mazes—or mostly interconnected. The metabolic enzymes responsible for supplying food and breaking down nutrients for energy did not even appear on Dang’s diagrams. They had their own separate diagrams, and those became increasingly hard to find in molecular biology labs in the 1980s.

Dang was thus surprised when in 1997, after more than a decade of tracing MYC’s influence on cells, he found that it spread to the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). As one of the key players in fermentation, LDH was not supposed to be linked with an oncogene. It was one of the housekeeping enzymes that belonged on the other diagram, the metabolism diagram. Dang had followed MYC to a place that wasn’t even on his original map.

Dang might have put the finding aside, but he had long felt that it was important to pay attention to discoveries that don’t seem to make any sense. Such findings, Dang says, can “teach you something.” So, instead of dismissing metabolic enzymes, Dang began to read as much as he could about them. That reading quickly led him to Otto Warburg, who had isolated LDH and explained its role in fermentation some 60 years earlier.

The literature from Warburg’s day confirmed what Dang had found: LDH activity was elevated in cancer. MYC, when overexpressed, wasn’t only driving cells to divide more often than they should. It was also driving them to eat and ferment more than they should.

“The perception was that metabolism was just there to support everything else,” Dang said. And yet the more Dang read and reflected, the less sensible it seemed to think of metabolism as somehow separate from the rest of the cancer cell’s activities. Cancer was like a building project, and the different teams on the project had to work together. “It has to be a coordinated process so that you can build things in an orderly way,” as Dang put it. “The bricks and the cement don’t somehow magically end up where they’re supposed to be.”10

DANG’S PAPER ON MYC and LDH, published in 1997, was initially met with great skepticism from most of his colleagues. The lack of enthusiasm for his work came as no surprise. Dang knew that the study of cellular metabolism was out of fashion. But then something happened that did truly surprise Dang. A colleague took him aside and told him that the negative reaction to his findings might also have something to do with the lingering resentment older Jewish researchers felt toward Warburg for his decision to stay in Nazi Germany—and perhaps the fact that he survived with relatively little trouble.

It was not an entirely outlandish idea. Warburg himself came to believe that Jewish researchers had turned against him for precisely this reason. And it’s true that various Jewish scientists had challenged Warburg’s claims about cancer and photosynthesis after the war. But then, countless scientists, Jews and Gentiles alike, resented Warburg for all sorts of good reasons. And it was not only the Jewish scientists who thought that Warburg was wrong about both photosynthesis and cancer.11

It’s possible that Warburg’s reputation made it easier for some researchers to leave his metabolic understanding of cancer behind as the new era of molecular biology set in. In 2000, Robert Weinberg, a pioneering oncogene researcher, coauthored a seminal paper, “The Hallmarks of Cancer,” which listed six fundamental changes in a cell that make cancer possible. The increase in glucose consumption and fermentation characterized by the Warburg effect was not one of them. Weinberg, who also failed to so much as mention Warburg in the first edition of his highly regarded 2006 cancer textbook, makes no secret of his distaste for Warburg. “I confess to harboring very negative feelings about Warburg because of his Nazi affiliations,” he said. Weinberg explained that Warburg’s story was personal for him, as his own parents had fled Germany in 1938.

Even so, Weinberg insists that his resentment of Warburg did not influence his work. Weinberg ignored Warburg, he explained, because he does not believe that “altered carbohydrate metabolism of cancer cells” is “the root cause of their aberrant behavior.” Besides, virtually everyone was ignoring Warburg and metabolism. “By the time I became deeply immersed in cancer research, Warburg was more of a historical relic,” Weinberg said, “almost a forgotten footnote in history.”

In Weinberg’s view, the anger at Warburg was not widespread and was not, ultimately, about his past in Nazi Germany. What most scientists disliked about Warburg, rather, was his “simplistic depiction of cancer” and “his imperious, Prussian style of handing down judgments” from his “self-imagined throne.”12

Weinberg’s assessment is probably correct. In fact, many of Warburg’s most loyal supporters after the war, including David Nachmansohn, Hans Krebs, and Harry Goldblatt, were Jewish. The best explanation for the “anti-Warburgian disease entity,” as Warburg once referred to the sentiment against him, was not Warburg’s political judgment before and during the war. It was his scientific judgment after the war.13

IF CHI VAN DANG HAD been the only scientist rediscovering Warburg in the late 1990s, it’s possible that the supposed “anti-Warburgian disease entity” would have continued to shape scientific opinion. But as Dang was reading through scientific papers from the 1930s, Craig Thompson, now the president and CEO of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, was beginning his own circuitous journey back to Warburg. Like Dang, Thompson came of age during a period when Warburg’s science was thought to be obsolete. “Nobody wanted to do biochemistry because all the great discoveries had been made,” Thompson said. “The feeling at the time was, ‘Let’s do cool stuff.’ ”

Thompson has a reputation for brashness. He played soccer at Dartmouth, but quit the team when his coach asked him to focus more on training and less on science. Shortly thereafter, Thompson decided he was done not only with soccer but with college as well. In 1972, he applied to Dartmouth’s medical school as a 19-year-old sophomore and was accepted—even after getting into a shouting match with the doctor who had interviewed him.14

By the mid-1990s, Thompson was doing “cool stuff” at his own lab at the University of Chicago. His focus was not cancer but immunology, and he had arrived at a fundamental question. When someone develops an infection, the immune system responds by rallying an army of cells to attack the invaders. The result, if the response is strong enough, is a swollen mass that, like a tumor, forms from rapidly growing and dividing cells. But the new immune cells, unlike cancer cells, are only temporary workers. As the underlying infection heals, the cells, no longer needed, begin to die off. It was this disappearing act, an act of collective suicide, that had captured Thompson’s imagination. How, he wondered, does the body distinguish between cells that are chosen to live and cells that are chosen to die, so that only the unwanted cells are eliminated?

It wasn’t a new question. August Weismann, the celebrated German evolutionary biologist, whose lectures Otto Warburg had attended at the University of Freiburg, had marveled over the organized death of cells more than a century earlier. The phenomenon is now known as “programmed cell death,” or “apoptosis,” from the Greek for “falling off.” Though long overlooked, apoptosis is arguably as fundamental to the biology of multicellular organisms as cell division. During the development of an embryo, apoptosis, like a sculptor chipping away at a stone to reveal a human form, helps shape our bodies. (If not for apoptosis killing off the connective tissue, our fingers and toes would be webbed.) Even as our cells grow and multiply, they never stop dying. Approximately 10 billion cells are thought to die in a person every single day. In some cases, as with immune cells after an infection, the cells die because they no longer serve a purpose. In other cases, apoptosis rids the body of cells that are damaged beyond repair.

Despite the fundamental role of apoptosis in biology, the precise mechanisms that govern the process remained unclear well into Thompson’s time. In a sense, he was trying to solve a murder mystery. And he had a suspect: a group of proteins known as the BCL-2 family. From work conducted in other labs, it was clear that the BCL-2 proteins had a role in cell death, but exactly what the proteins were doing, Thompson couldn’t say. Most curious of all, the BCL-2 proteins were interacting with the mitochondria, the tiny power stations of the cell.

The involvement of the mitochondria in apoptosis made the mystery all the more intriguing. In 1913, Warburg had made an important observation while examining the liver cells of a guinea pig. The cells were able to breathe oxygen, he suspected, thanks to small particles he could see inside the cells under his microscope. Warburg called the particles “grana” and refused to call them anything but “grana” for the rest of his life—long after the rest of the scientific world had begun to refer to them as mitochondria.15

Thompson had at once arrived at an exciting finding and a fairly significant problem: no one in the new world of molecular biology knew anything about the mitochondria. The mitochondria were part of the old world of biochemistry, the world of Warburg and his colleagues, the world that modern molecular biology was supposed to have left behind decades earlier.

If Thompson was going to make any progress in understanding how the body gets rid of unneeded cells, some unlucky soul in his lab would first have to relearn the science of a bygone era. It was exactly the sort of job one gives to the person who is least able to object. In Thompson’s Chicago lab, that person was a new arrival, Matthew Vander Heiden, a soft-spoken Midwesterner who was just beginning his MD-PhD.

In some ways, Vander Heiden was Thompson’s opposite. A product of a small Wisconsin town once known for its lawn mower factories, he discovered his love of research while washing equipment in a lab as part of a work-study job. And he was a better fit for a return to outdated science than Thompson could have known. Vander Heiden’s wife, the biologist Brooke Bevis, said that her husband struggles to throw anything out that he can still use, be it his watch, his phone, pots and pans, or laboratory equipment. “The list goes on and on,” Bevis said. “He carries his Midwestern sensibilities with him everywhere he goes.”16

To refamiliarize himself with mitochondria, Vander Heiden turned back to his old biochemistry textbooks from college. The textbooks were full of useful facts on the subject. He read about the work of Lynn Margulis, the legendary evolutionary biologist who had studied at Chicago 40 years earlier. Margulis had revealed the remarkable origins of the mitochondria: they are descendants of ancient bacteria that moved inside another unicellular organism more than a billion years ago.

It turned out to be a symbiotic relationship, and it would give rise to the eukaryotic cells that form the building blocks of all plants and animals. The mitochondria could burn food with oxygen; the host cell could ferment. This is why our cells, as Warburg put it, have “two engines.” Though the two organisms evolved together, the mitochondria held on to a small number of their own genes. Even at the cellular level, we have split personalities.

Vander Heiden’s old biochemistry textbooks were less exciting when it came to the role of the mitochondria in the cell, which was thought to be fairly one-dimensional and completely figured out. The mitochondria were understood to be the power source in the basement of the cellular building. They supplied energy and heat so that the genuinely interesting aspects of molecular life could continue.

In need of additional expertise on mitochondria and metabolism, Vander Heiden teamed up with Navdeep Chandel, of Northwestern University, who was then a cellular physiology student in another University of Chicago lab and among the few young researchers of the era interested in the structure of mitochondria.

In 1996, as the two began to run experiments on BCL-2 proteins, Xiaodong Wang, a researcher then at Emory University, made a stunning discovery: The mitochondria, it turned out, weren’t peripherally involved in the suicide process. They were driving it. When the mitochondria are no longer able to function, either due to cellular damage or lack of fuel, they collapse and send out a signal that triggers other proteins outside the mitochondria to begin slicing up the cell.

That a cell’s mitochondria could kill it from the inside was a shock in itself. The mitochondria’s relationship to the host cell suddenly looked more sinister than symbiotic. Stranger still was the manner in which a mitochondrion’s death signals went out. As the cellular machinery that burns food comes to a halt, a mitochondrion’s outer membrane bursts open, allowing the molecules inside, like refugees fleeing a burning city, to rush out. Among the fleeing molecules is cytochrome c, an enzyme that allows us to breathe by passing electrons to oxygen. And cytochrome c, of all molecules, is critical to activating the death signal. “Nothing in biology quite compares with this two-faced Janus,” as the biochemist and author Nick Lane put it. The very same protein that gives us life had been revealed to also be an assassin.17

Once it became clear that the mitochondria were directing apoptosis, Vander Heiden and Chandel could piece together the role of BCL-2 proteins. Like emergency workers fixing leaks in a dam before a storm, the proteins would fill pores in the mitochondrial membrane, keeping the charges inside and outside of the membrane in balance and preventing the escape of cytochrome c. Electrons would continue to make their way to oxygen and the given mitochondrion would continue to function.

But if a mitochondrion was too damaged or unable to obtain food or oxygen, the dam would no longer hold. Sensing the mitochondrion failing, other proteins from the BCL-2 family would open additional pores in the membrane and the entire system would collapse, allowing cytochrome c to escape and alerting the cell that a brownout was underway. A single failing mitochondrion wouldn’t trigger cell death, but if enough of the mitochondria began to fail, the brownout would become a blackout and the cell would self-destruct.

Even more important than the precise mechanisms of apoptosis was the broader picture coming into focus for Vander Heiden: the common understanding of the causal arrow of cellular life, it increasingly seemed, was backward. The energy-releasing reactions inside the mitochondria weren’t only responding to the cell’s needs. They were also dictating what a cell should do, governing even the cell’s most important decision of all: whether to live or die.

Vander Heiden remembers the breakthrough on apoptosis as a “watershed moment.” The feeling, he said, was, “Oh my goodness. We don’t really understand metabolism.” But almost as surprising as the new thinking on metabolism in Thompson’s lab was that so few others were interested in it outside of the lab. “It’s as fundamental as you get in terms of how biology works,” Vander Heiden said. “I looked around, and no one was studying it.”18

CRAIG THOMPSON HAD set out to understand how the body eliminates immune cells when they’re no longer needed. Vander Heiden and Chandel’s research on the mitochondria and apoptosis helped provide at least part of the answer. Millions of unwanted immune cells being driven to commit suicide meant something was undermining their mitochondrial power stations. Thompson wanted to determine what that something was.

He turned his attention to the messengers that instruct our cells to stay alive and grow. Owing to the work of the biologist Martin Raff, among others, it was already known that such growth factors are necessary to prevent cells from turning to apoptosis. When the signals don’t arrive from other cells, the suicide process is referred to as “death by neglect.” Raff once remarked that every cell in the body wakes up each morning thinking about suicide and has to be talked out of it by its nearest neighbors.

If Thompson already knew that growth factors were likely part of the story and that they had to eliminate cells by way of the mitochondria, he didn’t yet know how the process unfolded. Jeff Rathmell, then a young researcher in Thompson’s lab (he now runs his own lab at Vanderbilt University), began to work with Vander Heiden to find answers. In one experiment, Rathmell took a single human cell and placed it in a small dish that contained the glucose and other nutrients the cell needed to grow and thrive. It was an environment, as Thompson put it, “that would keep a yeast cell happy for the rest of its life.”19 And yet, when Rathmell examined the lonely cell, he did not find a picture of happiness. Without growth factors telling it to take up nutrients, the cell went on a hunger strike. The lack of food would be registered by its mitochondria, and within 48 hours, the cell would die by apoptosis. Rathmell repeated the test again and again with different cell types, and the results were always the same.

The body gets rid of unwanted cells, Thompson and his colleagues realized, by cutting off growth factors and starving the cells into suicide. As Thompson described the process, as cells learned to live together as collectives, tough sacrifices had to be made. What cells “really gave up as multicellular organisms,” he explained, was the freedom to eat.20

Craig Thompson was still running an immunology lab, but the more he learned about how cells die, the more he found himself thinking about cancer. Cancer cells were the opposite of the isolated cells that refused to eat. They were cells that ate whenever they felt like it, cells that couldn’t be starved into suicide, even though they had no purpose in the body. “Cancer really is saying, ‘Let’s override all the control and just grow whenever there’s nutrient availability,’ ” said Lewis Cantley, director of the Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. “It’s just going back to the wild.”21

With each new finding, Thompson grew more confident that a return to metabolism was going to transform modern molecular biology and open up new avenues of cancer research. Rathmell was much less sure. For all his excitement about his research, the Warburg revival was only in its infancy. In the late 1990s, academic journals still weren’t interested in publishing papers on metabolism. With the exception of Chi Van Dang and a small number of holdouts from the Warburg era, such as Peter Pedersen at Johns Hopkins, almost no one saw a future for the field. To the outside world, it still looked as though Thompson’s lab was attempting to make sense of a vastly complicated construction site by studying the trucks showing up with fuel.22

Rathmell became particularly concerned after attending a major scientific conference where he and other postdoctoral researchers presented their work on posters. At these “poster sessions,” young scientists stand by their presentations as older and more established colleagues amble by. Waiting silently by his poster, Rathmell felt as isolated as one of the cells in his experiments. “There were 400 people walking around in this relatively small space and only one person stopped at my poster,” he recalled. “And that person stopped to tell me that I was wrong and wasting my time.”

And so, in 1999, when Thompson decided to relocate to the University of Pennsylvania and devote his research program to metabolism, Rathmell had reason to worry. As Thompson remembered it, Rathmell told him that he might be jeopardizing the careers of all the young scientists in his lab. Thompson, confident as ever, encouraged his students to stick it out. He had a new agenda: to identify the specific genes that allow a cell to eat without permission from growth factors. Thompson thought that if he could identify these genes, it might do more than bring Warburg’s metabolism research into the age of molecular biology. It might also explain why we get cancer.23