Automate the Web

You might not think of Web browsing as an activity that requires automation. You follow links, you read articles, watch cat videos, maybe make the occasional purchase, but that’s all inherently manual, right? After all, I don’t want my Mac to read Facebook posts for me or play games behind my back.

But in fact, the Web offers numerous opportunities for shortcuts and simplification. For example, every time you’re asked to supply a username and password, a credit card number, or a mailing address, your Mac can do that for you—no typing (or memorizing) required.

Here’s another example: you keep checking a certain Web page—or maybe a specific portion of a page—for changes. Maybe you’re waiting for an announcement, a sale, or a product update, or maybe you’re looking for news stories about your neighborhood. Repeatedly checking a page for changes (whether once a day or several times a minute) is exactly the sort of labor-saving task computers are good at.

And then, looking more generally at cloud services that just happen to have a Web presence, there are tons of opportunities for connecting things. Perhaps you always want to post photos to Facebook after they appear in a particular shared Dropbox folder. Or you want to save links from your favorite tweets to Instapaper. Or you want to see an alert in the evening if tomorrow’s weather forecast calls for rain. All sorts of things that can occur in one cloud service can trigger events in other cloud services—an area ripe for automation.

Log In Faster with iCloud Keychain and Safari Autofill

Let’s begin with an easy way to automate filling out all those pesky Web forms, without the need for any extra software.

The Mac version of Safari (like nearly all Web browsers) can automatically fill in your contact information (name, address, phone number, and so on), as well as usernames and passwords, on Web forms. Safari uses OS X’s system-wide keychain mechanism to securely store the portions of this data that aren’t already in your Contacts app.

iCloud Keychain, a feature introduced in Mavericks and iOS 7, extends this capability. It lets you sync a keychain across your Apple devices securely via the cloud. The biggest benefit is that Safari for iOS can now autofill usernames and passwords that you stored in a keychain on your Mac (and vice-versa). But that’s not all, iCloud Keychain also includes:

- A strong password generator built into Safari (on both platforms)

- The capability to store, sync, and enter credit card information (except the CVV number from the back of the card) in Web forms

- Support for multiple sets of credentials per site

- A new way to view and remove passwords within Safari

In addition, if you turn on iCloud Keychain, it will automatically sync the settings for the accounts listed in the Internet Accounts pane of System Preferences on your Mac (including email accounts, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn) amongst your other Macs. This account syncing does not extend to iOS devices.

Enable and Configure iCloud Keychain

The short version of setting up iCloud Keychain is: go to System Preferences > iCloud, select the Keychain checkbox, and enter your Apple ID password. Repeat on your other devices. However, unlike most iCloud features, flipping a single switch isn’t all there is to it here; the initial setup process is actually more involved. Also, the steps you follow with whichever device you set up first will be different from the steps for setting up all subsequent devices.

If you haven’t already set up iCloud Keychain—or if you suspect you might have less-than-optimal settings—I encourage you to read my Macworld article How to use iCloud Keychain, which spells out the steps and options in detail.

Once you’ve got everything set up and your keychain is syncing between devices, you can start using data (and adding to it) in Safari. (So far, iCloud Keychain works in Safari but not in any third-party browsers, although that could change in the future.) The behavior is similar on OS X and iOS.

Enable iCloud Keychain Features in Safari

First, make sure Safari is set up to use all of iCloud Keychain’s features.

On a Mac, open Safari and then choose Safari > Preferences. Click AutoFill, and make sure the checkboxes are selected for each type of data you want to autofill—the two options relevant to iCloud Keychain are User Names and Passwords and Credit Cards. (While you’re at it, you might also want to enable Using Info from My Contacts Card and Other Forms. Even though that data isn’t stored in iCloud Keychain, it’s useful to be able to autofill it.)

On an iOS device, tap Settings > Safari > Passwords & AutoFill, and turn on Names and Passwords and Credit Cards.

Autofill Passwords

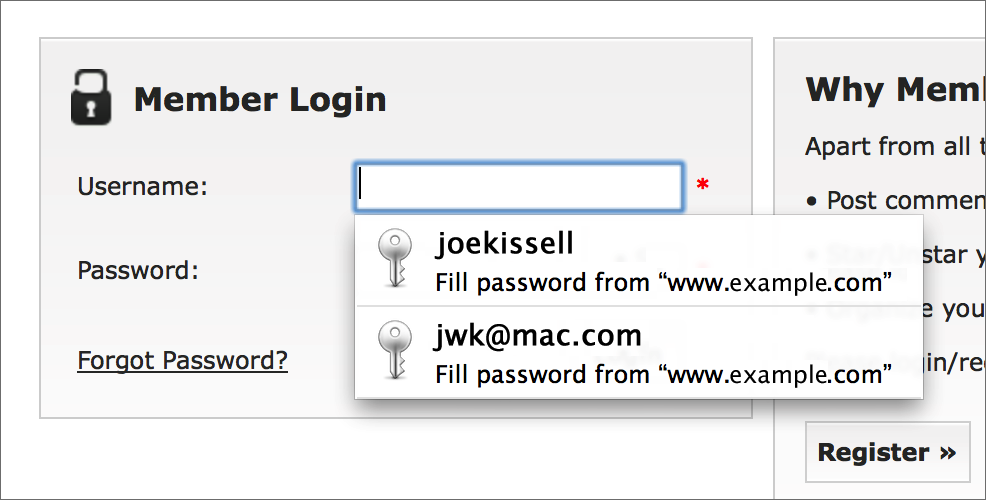

When you load a page for which you’ve already stored credentials in your iCloud Keychain, Safari fills in the Username and Password fields for you—all you need to do is click or tap Login (or a similar button). If you’ve stored more than one set of credentials for a site—for example, if you have two different accounts for Google or Twitter—you can click or tap in the Username field to display a pop-up menu (Figure 25) with your logins; choose the one you want to fill in your credentials.

Figure 25: If you have multiple credentials for a site, click or tap in the Username field to display a pop-up menu and then choose one.

Some Web sites deliberately block browsers and password managers from saving passwords you enter there, in a misguided attempt at greater security. Earlier versions of Safari had a preference that, when enabled, forced Safari to override some of these blocks, but as of 10.9.2 Mavericks, that preference no longer exists—it’s entirely up to Safari whether to accept or attempt to bypass any site’s restrictions. And guess what? One notable site where iCloud Keychain can’t autofill your password is…icloud.com! That seems like an awful oversight, and I hope Apple changes it soon.

Store New Passwords

If you arrive at a login page for which iCloud Keychain does not yet contain your credentials, enter them manually (or with a third-party password manager) and log in. Safari should then display a prompt asking if you want to save the password in your iCloud Keychain. Click Save Password to store your credentials for that site.

If you already have credentials stored for the site and you want to store an additional username/password combination, first delete the credentials Safari has autofilled. Then enter the new credentials, log in, and click Save Password when prompted.

Generate a Random Password

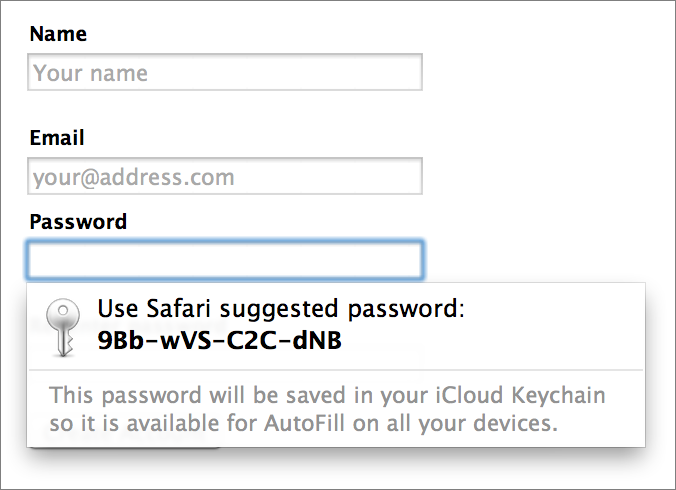

When you’re asked to register on a Web site and create a new password, iCloud Keychain can generate one for you and store it all in one step. First, make sure the Password field is completely empty. Then click or tap in it to display a random password (Figure 26). Click or tap the password to fill it in (if there’s a Repeat Password field, Safari fills the password there too). Safari also saves your credentials for the site without any additional steps.

Figure 26: Click or tap in a blank Password field to see a suggested random password.

Store and Enter Credit Card Numbers

Credit cards work much like passwords—if you type or paste a credit card number into a blank field (along with its expiration date) and submit the form, Safari prompts you to save the credit card number in your iCloud Keychain. (Remember, it doesn’t save or store the CVV number from the back of your credit card.)

When it’s time to fill in a stored credit card number, click or tap in the Credit Card Number field and choose the desired credit card from the pop-up menu.

Autofill Other Data

I mentioned that you might want to enable Safari’s two other autofill features in Safari > Preferences > Autofill. The first, Using Info from My Contacts Card, populates form fields with your contact information when appropriate. The second, Other Forms, does the same thing for anything you’ve previously filled in on a form that isn’t part of your credentials, credit card, or contact information—that might include preferences, survey questions, or nearly anything else.

As you browse the Web, if Other Forms is selected, Safari remembers everything you enter in a form field.

Later, if you want to fill that in on the same site—or if you want to fill in your contact information—you have two choices:

- Choose Edit > AutoFill Form (Command-Shift-A).

- Start typing your contact information in any form field. When Safari sees that it matches the corresponding information from your card in Contacts, it pops up a little card icon labeled “AutoFill your contact info.” Click this icon or press the Down Arrow key to select it, and then click AutoFill (or press Return) to fill in the rest of the form.

Automate Web Logins with a Password Manager

Although the combination of Safari and iCloud Keychain can simplify entering most form data, you might want to consider (instead or in addition) a third-party password manager. Why would you pay for something that’s built into OS X and iOS? Well, third-party tools can do several important things that iCloud Keychain can’t:

- Work on older versions of Mac OS X, as well as non-Apple platforms (Android, Windows, Linux)

- Generate stronger random passwords to your exact specifications (length, case, numbers, special characters, and so on)

- Autofill credentials in other OS X browsers (Google Chrome, Firefox, Web Aviator)

- Store and fill in multiple sets of contact data (such as home and work)

- Fill in your credit cards’ CVV numbers, so you don’t have to dig them out of your wallet every time you make a Web purchase

- Store a broader range of information types, including software licenses, passports, memberships, and reward programs

- Provide a friendlier interface for viewing and editing data than Apple’s awful Keychain Access utility

For all these reasons, although I use and appreciate iCloud Keychain, I rely more heavily on a password manager called 1Password. It syncs all my data amongst my Macs and iOS devices, as well as Windows and Android devices. It has lots of useful organizational features. And, it gives me a greater feeling of control over my passwords than iCloud Keychain does. When I get to a Web page that asks for my credentials, I simply press the default keyboard shortcut Command-\, and 1Password fills them in and submits the form. Piece of cake.

In fact, I like 1Password so much I wrote a book about it: Take Control of 1Password. If you choose to use 1Password, you may find that book helpful in getting up to speed.

However, 1Password is not by any means the only game in town. Other third-party password managers that have most of the same features (and thus, the same advantages over iCloud Keychain) include Dashlane, LastPass, and RoboForm. I’ve tried them all and would happily recommend any of them.

Automate Cloud Services

Hundreds of apps, sites, services, and other products proclaim their connections to the cloud, even though it’s often unclear what “cloud” means or what its benefits are. A consequence of this cloud craze is that you can end up with dozens of accounts with cloud services that partially overlap in capabilities. Yet for the most part, these services don’t communicate with each other. The result is that you may end up spending a lot of time taking a file, photo, or piece of information from one cloud service and moving or posting it to another service.

Luckily, a few sites have emerged whose entire purpose is to connect cloud services for you, automating the cloud so that useful things happen in one service when something happens in another.

Let me give you some concrete examples of how multiple cloud services can be connected and automated:

- Add something to the Reminders app (in OS X or iOS) and it’s copied to an Evernote checklist.

- When someone tags you in a Facebook photo, download that photo to your Dropbox.

- Post an Instagram photo and have it automatically sent to Twitter too.

- Save all your incoming email attachments to your OneDrive.

- Send a thank-you note by email whenever someone endorses you on LinkedIn.

Got the idea? Let’s look at three sites that let you do those sorts of things.

IFTTT

IFTTT (for If This, Then That) is the best-known and most popular site in this category. The name describes the concept: you create two-part “recipes” that say: If this happens (in one cloud service), then do that (in a second service). These formulations are a bit like email rules, except that there’s always exactly one condition and one action—simple.

What services can you connect? Why, there are well over 100 of them, which IFTTT refers to as “channels,” covering almost every major cloud storage platform (Box, Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive…), social network (Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Foursquare…), and photo site (Flickr, Instagram, 500px…), plus iOS data (contacts, location, notifications, photos, reminders), email, blog platforms, news sites, and even things like the date, time, and weather. The list is growing all the time.

IFTTT is free. After signing up for an account, you activate whichever channels you’re interested in by signing in to the relevant accounts. Then you can choose from any of tens of thousands of pre-built recipes, or concoct your own as follows:

- Click Create.

- Click the word

this. - Click a trigger channel—where you look for the new piece of data that will kick off the recipe.

- Fill in any necessary information (the options vary by channel). For example, if your trigger channel is Facebook, you click one or more links to specify what particular activity in your Facebook account you want to use (such as “You are tagged in a photo”). click Create Trigger.

- Now click the word

that. - Click an action channel—where the information from the trigger channel will be sent.

- Once again, specify any details necessary to complete the action, such as whether you want to download a photo or have its URL added to a text file.

- Click Create Action.

- Finally, click Create Recipe.

That’s it! Your recipe now runs by itself, automatically taking the action you specified when the trigger occurs.

Zapier

Like IFTTT, Zapier combines a single trigger and a single action into an automated tool, called a Zap. Also like IFTTT, there are thousands of prebuilt Zaps to choose from, or you can create your own using any of over 250 cloud services. Careful readers will notice that “over 250” is a much larger number than IFTTT’s “over 100.” However, many of Zapier’s options are either obscure or available only with premium (paid) subscriptions.

Speaking of which: Zapier is free for up to 5 Zaps, 100 tasks per month, and 15-minute intervals between Zaps. If you want more Zaps, more tasks per month, and/or more-frequent Zaps—as well as those extra cloud services available only to paid subscribers—you’ll have to pony up anywhere from $15 to $99 per month.

Those numbers, and the names of the premium services (Amazon S3, GoToMeeting, Salesforce, ZOHO CRM, and so on), reflect Zapier’s business focus. Likewise, the use cases detailed on Zapier’s site are all about customer support, marketing, operations, and sales—not the sorts of things most ordinary consumers care about.

All that to say: Zapier is plenty powerful, but even though it has some nifty features that IFTTT lacks, I find it less approachable, and less applicable to my personal needs, than IFTTT.

Wappwolf Automator

A company called Wappwolf offers three nearly identical services: Automator for Dropbox, Automator for Google Drive, and Automator for Box. In each case, you set up actions that watch particular folders in a cloud storage service, and when something is added to one of those folders, any of a few dozen actions can occur, such as:

- Converting a document to PDF

- Uploading a graphic to Facebook

- Sending a tweet

- Resizing a graphic

- Emailing a file

- Uploading a file to a different cloud service

So, it’s along the same lines as the other services I’ve covered here, except that it’s less flexible on the trigger end—only making a change to a folder synced to the cloud can prompt an action. Basic plans are free, with some limits; you can remove most of the limits for a small monthly fee.

Discover Other Web Automation Options

Connecting cloud services is fantastically useful, but sometimes you may need something a bit simpler and more elegant. For example, you might want to monitor the Web (as a whole) for new pages on a topic of interest, or monitor a specific page for changes.

Monitor the Web with Google Alerts

The Web changes continuously, so Google is constantly updating its massive index of the Web to provide up-to-date search results. As a result, a search you perform one day may yield completely different results than it did yesterday. If you’d like to stay on top of a given subject, you can use the free Google Alerts service to perform an automated search every day (or even more frequently, if you like) and send you any new results by email or a customized RSS feed.

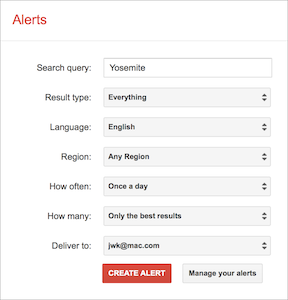

To use Google Alerts, you fill out a form (Figure 27) with your search query (just as if you were doing a regular Google search) and a few other pieces of information—most crucially, your email address (or choose Feed from the Deliver To pop-up menu to create an RSS feed). The current results of your query appear on the right. Click Create Alert, and you’re done—you’ll get the results automatically.

Figure 27: Create a Google Alert by filling out this form.

You can go back to the Google Alerts page whenever you like and click Manage Alerts to add, remove, or modify alerts.

Ideas for Google Alerts:

- Google yourself and find out when people are talking about you.

- Follow rumors about hypothetical new Apple devices.

- Get the latest news on treatments for a medical condition a loved one is experiencing.

- Search for discounts and deals on products you’re interested in.

- Keep tabs on your competition.

Use a Cloud Service to Monitor a Web Site for Changes

In the online appendixes to my book about backing up your Mac, I have tables listing the features of many backup apps and cloud services. This information changes all the time, though. One of the ways I keep that information (more or less) up to date is by monitoring the pages that list release notes or other version information for each of dozens of apps. When one of the pages changes, I check to see if the change is relevant to my table, and if so, I update the table accordingly.

Needless to say, I don’t manually check dozens of Web pages for changes every day! Instead, I use a free service that checks for me and sends me an email if any of my monitored pages has changed since the last time it checked.

I’ve used two such services—WatchThatPage, which is has a kind of awkward and old-fashioned interface, but gets the job done; and ChangeDetection.com, which is more modern and customizable. (For example, it can send change notices via a custom RSS feed, much like Google Alerts, and it can look for specific text that is added or removed.) Either way, the process is dead simple: sign up for a free account, enter a URL, and click a button to start monitoring it.

Other reasons to monitor Web sites for changes:

- Watch for schedule changes, special events, and other announcements from your child’s school.

- Find out the second any new Take Control book is published—even if you’re not on our mailing list!

- Learn about new products or price drops in the Apple Store.

- Get updates on your favorite crowdfunding projects from Kickstarter, Indiegogo, and the like.