Use a Macro Utility

Earlier, in Use OS X Automation Technologies, I discussed AppleScript and Automator, two tools that can control numerous other apps and tie multiple actions together into easy-t0-run shortcuts. Both of those technologies are powerful, free, and included with OS X. But AppleScript’s learning curve precludes casual use, while it’s limited by the capabilities various apps choose to expose. Automator is far easier for a beginner to use, but it, too, has a fairly constrained palette of capabilities—and not all the tasks you might wish to automate fit its “workflow” mold. Meanwhile, apps like Excel and Nisus Writer Pro have fantastic automation capabilities built in, but they’re largely confined to activities within those apps.

So we come to a category of automation tools that—at the risk of overstating my case—transcends these limitations. If you just want to get the job done—not necessarily in the most programmatically elegant way but in a fast, reliable, and flexible way—you want a macro utility. It’s the sort of tool I reach for most often for general-purpose automation tasks.

Like other kinds of tools covered in this book, the idea of a macro utility is straightforward. You pick an action, or a series of actions, from a list; these form the macro’s task. Then you pick one or more events to trigger that action—a keyboard shortcut, a button click, a change in network settings, or whatnot. That’s it: you have a macro.

What’s interesting about the utilities discussed in this chapter is that the lists of potential actions they offer as building blocks for macros are quite long and diverse. Some of these actions, similar to AppleScript verbs and Automator actions, directly control a particular app (iTunes, Safari, the Finder) or send instructions to OS X (shut down, change display brightness, switch users). Others manipulate behind-the-scenes resources (clipboards, variables, strings) or manage the flow of steps (if/then/else conditionals, loops, subroutines). Still others “play” the visible interface, simulating button presses, menu commands, keystrokes, and mouse movements.

Put all this together and you have a toolkit that—with a bit of cleverness and patient testing—can automate almost any repetitive Mac task that doesn’t require creativity or human intuition. Just a handful of examples, all of which can be done with a single click or keystroke:

- Remap keys on your keyboard to perform different functions

- Show the screen of a shared Mac

- Force a “stuck” Trash to empty

- Add keyboard shortcuts to menu commands in apps that don’t support OS X’s built-in shortcuts

- Create an ad hoc Wi-Fi network

- Open an entire set of apps and documents

- Resize and reposition all your windows so they don’t overlap

- Modify text or formatting according to predefined patterns

- Email the URL of the Web page you’re currently viewing to someone else

- Rotate, flip, resize, or crop all the images in a folder

Having thus sung the praises of macro utilities generally, I must level with you. For all practical purposes, we’re talking about one utility: Keyboard Maestro. Sure, I’ll mention a few others (in Use Another Macro Utility), and I don’t mean to diss them, but the main shortcoming of competitors like iKey and QuicKeys is that they aren’t being actively maintained or developed. They have excellent features, but they lack the latest bells and whistles, and don’t engender confidence that they’ll still work in tomorrow’s version of OS X. If you want a great macro utility—and trust me, you do—Keyboard Maestro is where it’s at.

Control Your Mac with Keyboard Maestro

I’ve already given you a taste of what Keyboard Maestro can do, so let me show you what it looks like, walk you through creating a couple of macros, and explore some of its options and little-known features.

Create a Macro

When you open the Keyboard Maestro (Figure 40), you’ll see a three-pane Editor interface. On the left is a list of groups, which you can use to organize your macros however you like; this includes the All Macros smart group. In the middle is the list of all the macros in the current group. And on the right is the contents of the currently selected macro (or a blank shell of a macro, if you’ve just created it). To create an empty macro, click the plus  button at the bottom of the Macros list.

button at the bottom of the Macros list.

Figure 40: The Keyboard Maestro editor with a new, blank macro ready to be customized.

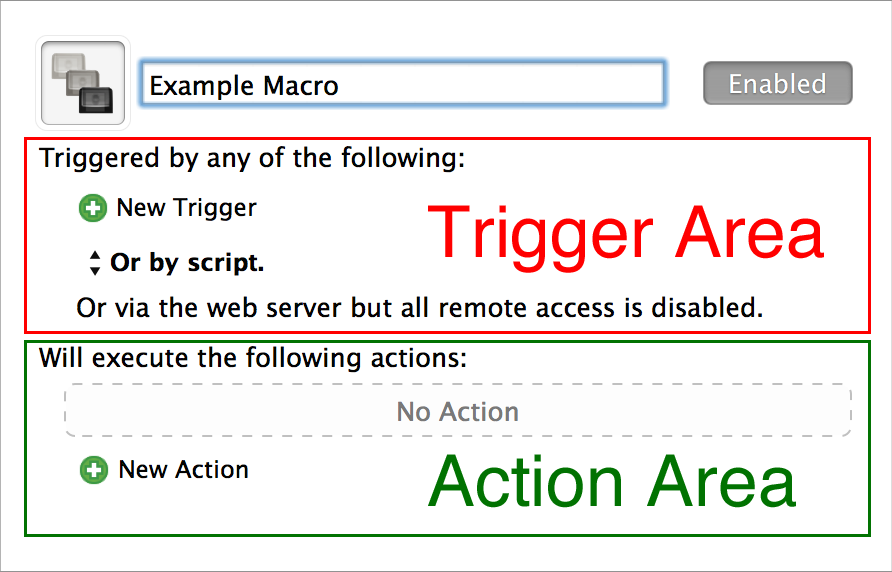

Within the macro pane (Figure 41), you see two areas: the trigger(s) (top) and the action(s) (bottom). You can configure these two items in any order. A trigger is what you do to make the macro run—a keystroke, a menu command, or a system event, say. (More about triggers in a moment.) The action(s) are what happen when the trigger occurs.

Figure 41: The macro pane includes trigger and action areas.

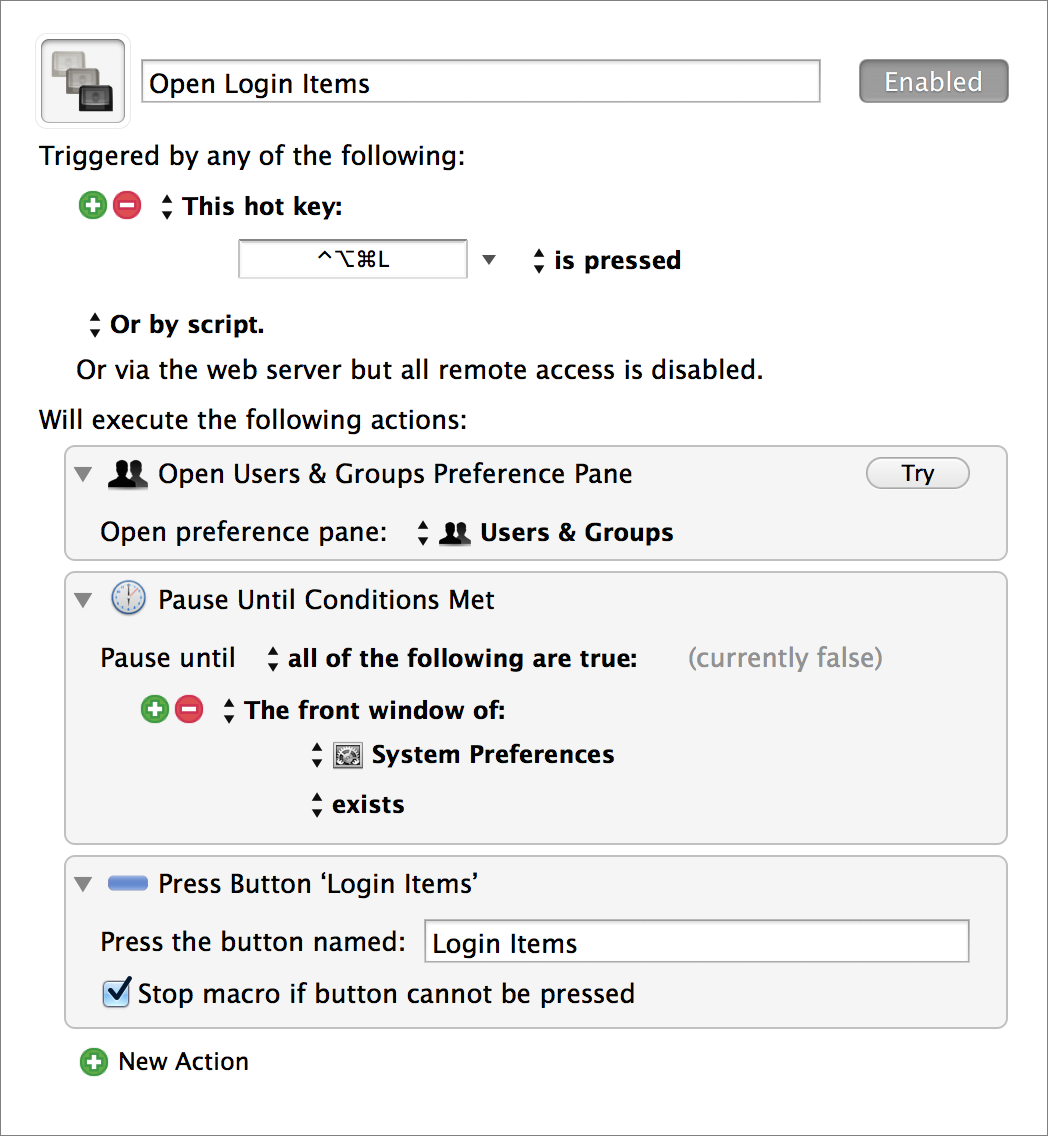

Macro #1: Open Login Items

For the sake of illustration, we’ll start by making a macro with a single, simple trigger and a sequence of three actions. When you run this macro, it will display the Users & Groups pane of System Preferences, with the Login Items list showing. (Ordinarily, you’d have to open System Preferences, click Users & Groups, and then, unless Login Items had been selected the previous time you viewed that pane, click Login Items. So, we’re replacing three clicks with one keyboard shortcut.)

Follow these steps:

- If you haven’t already done so, launch Keyboard Maestro, select a group (doesn’t matter which one), and click the plus

button at the bottom of the Macros list to create a new, blank macro.

button at the bottom of the Macros list to create a new, blank macro. - Give your macro a name—replace Untitled Macro at the top with

Open Login Items. - Click New Trigger to display a pop-up menu from which you can choose any of 16 trigger types. Choose Hot Key Trigger (the first item) from this menu to use a keyboard shortcut as the trigger.

- You’ll notice that the Type field under the text “This hot key” is already selected. So press the keyboard shortcut you want to use to trigger this macro. It can be anything you like, but I suggest choosing something obscure that isn’t already being used for something else, like Command-Option-Control-L.

- Click New Action to display a new pane (which covers the two leftmost columns of the window) with a list of all possible actions, grouped by category (Figure 42).

Figure 42: Keyboard Maestro’s actions are grouped by category.

- The first action is to open the User & Groups pane of System Preferences.

To do this, click Open in the Categories list and then drag Open a System Preference Pane to the “No Action” label on the right (or just double-click the action). If Users & Groups isn’t already shown next to “Open preference pane,” choose it from the pop-up menu.

- When you launch System Preferences, it may take a second or two to open, and we want to wait until it’s running to switch to the Login Items view.

So, select Control Flow in the Categories list and then drag the Pause Until action underneath the Open Users & Groups Preference Pane action. Click New Condition and choose Front Window Condition from the pop-up menu. Then, from the Front Application pop-up menu, choose System Preferences (if it’s not already there, click More at the bottom to expand the list). Leave the last pop-up menu set to Exists.

- Now we need to switch to the Login Items view (in case that’s not what the window is currently set to).

Click Interface Control in the Categories list, and add the Press a Button action to the end of your action list. Replace the text OK with

Login Items. At this point, the macro should look like Figure 43.

Figure 43: The final Open Login Items macro, in edit mode.

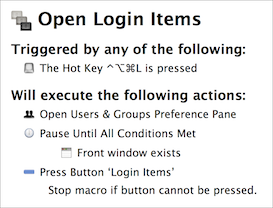

- Click the Edit button at the bottom to deselect it. Once you’re no longer in edit mode, the macro should look like Figure 44.

Figure 44: The final Open Login Items macro.

We’re ready to rock! Press Command-Option-Control-L (or whichever combination you chose). System Preferences should open to the Users & Groups pane, with the Login Items view visible.

Macro #2: Change Extensions

Back in Script the Command Line with Shell Scripts, I showed you a simple shell script that changes the extensions of all the files in a folder from .JPG to .jpeg. But I also said that the design of that script made it unsuitable for embedding in a launcher or macro utility.

Let me now show you one way to get the same result with Keyboard Maestro—without ever leaving the Finder, and with a little help from the command line. Follow these steps:

- Create a new macro (as you did in Macro #1: Open Login Items) and give it the name

Change Extensions. - Click New Trigger and click Status Menu Trigger from the pop-up menu. (This is just for variety, and so I can show you how the status menu works. Feel free to use other triggers instead or in addition.)

- Click New Action to display the Categories and Actions lists.

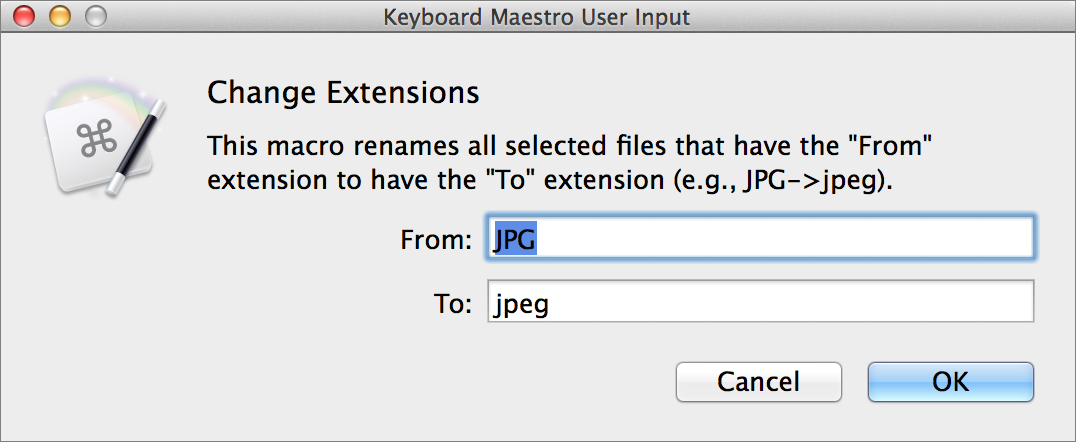

- Click Notifications in the Categories list, and then add the action Prompt for User Input as your first action. Fill it in with the following options:

- Title: Change Extensions

- Prompt:

This macro renames all selected files that have the "From" extension to have the "To" extension (e.g., JPG -> jpeg). - Variables and Default Values: Click plus

and then fill in

and then fill in Fromfor the first variable name,JPGfor its value; click plus again and fill in

again and fill in Tofor the second variable name andjpegfor its value. (Leave the remaining settings as is.)

- Click Control Flow in the Categories list and add For Each as the second action. In the For Each field, enter

filePath. Click plus and then choose The Finder’s Selection Collection from the pop-up menu. (Leave the Fix Finder Selection Bug option checked.)

and then choose The Finder’s Selection Collection from the pop-up menu. (Leave the Fix Finder Selection Bug option checked.) - Click Execute in the Categories list and drag Execute a Shell Script to the No Action field (under “execute the following actions”). (In other words, you’re embedding one action inside another.)

- In the Execute Shell Script action, make sure the first pop-up menu says Execute Text Script. Then type or paste the following into the text field exactly as shown here (including spaces):

base=`basename "$KMVAR_filePath" .$KMVAR_From` ext="${KMVAR_filePath##*.}" path=`dirname "$KMVAR_filePath"` if [ $ext == $KMVAR_From ] then mv "$KMVAR_filePath" "$path/$base.$KMVAR_To" fiYou’ll notice a few passing similarities to the shell script back in Script the Command Line with Shell Scripts, but also quite a few differences.

- Double-check to see that the macro looks like Figure 45.

Figure 45: The Change Extensions macro should look like this when it’s completely filled in.

- Optional but recommended: click the Edit button at the bottom to deselect it.

Now you can run the macro, but first you’ll need a folder somewhere with a few JPEG graphics in it. I suggest creating a test folder with duplicate images in it just so you don’t accidentally mess up your important photos if something goes wrong.

Since we’ll be modifying the extension, which is hidden by default in OS X, display all extensions temporarily in the Finder by going to Finder > Preferences > Advanced and selecting Show All Filename Extensions. (You can turn this off later, if you like.) Give some or all of your JPEGs the extension .JPG.

One last thing before we run the macro: if Keyboard Maestro’s status  or

or  menu isn’t already visible in your Mac’s menu bar, switch back to Keyboard Maestro, go to Keyboard Maestro > Preferences > General and make sure Display Status Menu is set to either Alphabetically, By Group, or Hierarchically (i.e., not Never).

menu isn’t already visible in your Mac’s menu bar, switch back to Keyboard Maestro, go to Keyboard Maestro > Preferences > General and make sure Display Status Menu is set to either Alphabetically, By Group, or Hierarchically (i.e., not Never).

Now select all the files in your test folder. (Or at least, select a bunch of files, some of which have the .JPG extension.) Then choose Change Extensions from the Keyboard Maestro status  or

or  menu. You should see the dialog (which you created!) shown in Figure 46.

menu. You should see the dialog (which you created!) shown in Figure 46.

Figure 46: This dialog should appear when you run your macro.

Leave the options at their defaults and click OK. The extensions on selected files that were previously .JPG should change to .jpeg. (Feel free to run the macro as often as you like, with different From and To settings and different files selected to see how it works.)

Record a Macro

If you read Automate Microsoft Office, you may recall that in Office apps, you can record a macro. In other words, Office will watch you while you perform activities, and then make them into a macro. You can play this macro back later, no coding required. Keyboard Maestro offers a similar feature. It won’t always produce results as reliable as creating your own macro from scratch—and not every kind of macro can be recorded—but it’s a simple way to ease into macro construction or get unstuck if you’re stuck.

To record a macro:

- Create a new macro, just as in the earlier examples, and give it a name and trigger.

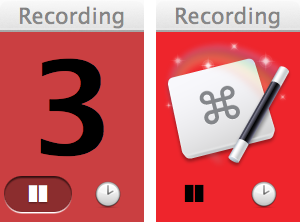

- Instead of filling in actions, click the Record button at the very bottom of the window. A little 5-second countdown timer appears on screen (Figure 47).

Figure 47: This floating window appears when you record a macro. The countdown timer (left) gives way to the icon on right when it reaches zero.

- Once the timer has counted down to zero and the icon says Recording, do stuff. Whatever you like. Switch apps, type text, apply formatting, choose menu commands, click buttons, anything. You know, stuff.

- Click the floating Recording icon to stop recording and examine your new macro in Keyboard Maestro.

- Optional but recommended: click Edit to leave edit mode.

Now try running your macro. If the macro doesn’t work as expected—which is likely—go back and click Edit to return to edit mode and see if you can modify some of the actions to do what you want them to do. You may also need to add Pause or Pause Until actions to force the macro to wait for your Mac to catch up with it at certain points.

Learn about Keyboard Maestro Actions

I’ve shown you a handful of actions in the course of walking you through the sample macros. There are many, many more of them. You can learn about actions by looking at the Keyboard Maestro documentation, or by trying them out. I’d like to point out just a few actions and categories that I find particularly interesting:

- Activate Clipboard History Switcher (Switchers category): I mentioned in Use a Macro or Launcher Utility that Keyboard Maestro is also an excellent clipboard utility, featuring its own clipboard history. This action displays a floating window with that history.

- Filter Clipboard (Clipboard category): On the clipboard theme, this action can make a wide variety of changes to the contents of your clipboard—remove styles, change case, perform a calculation, count words, and more.

- Google Chrome Control category, Safari Control category: Thanks to the actions in these categories, you can automate nearly anything in Google Chrome or Safari—you can open a Web page, fill in and submit a form, click buttons, create new tabs, execute JavaScripts, and more.

- Execute category: If your macro needs capabilities that Keyboard Maestro’s built-in actions don’t provide, you can use the actions in this category to run a shell script (as we did in Macro #2: Change Extensions), an AppleScript, or an Automator workflow as part of your macro. (You can also apply a BBEdit text factory—look in the Clipboard category.)

- Find Image on Screen (Image category): This blew my mind when I first saw it. Keyboard Maestro can identify an area on your screen matching an image (perhaps a cropped screenshot) that you supply, and having found that portion of your screen, it can highlight it, move the mouse to it, or take other actions.

Alternatively, a macro can choose to do something or not based on whether an arbitrary portion of your screen matches an image. As just one example of why this is interesting, a blind reader wrote to tell me he uses this feature, in conjunction with AppleScript, to speak the status of an icon on his screen (enabled or disabled) that he’d have no other way to determine because it’s unavailable to VoiceOver. I think that’s incredibly cool. To learn more about using this action, read How to Assign a Hotkey to Almost Anything by Patrick Welker.

- Variables category: We used two variables in Macro #2: Change Extensions to pass the contents of fields in a dialog to a shell script. There are countless other ways to use variables, but what I find most valuable is that they’re able to take information created or discovered by one action and reuse them in another action, later in the macro.

Learn about Keyboard Maestro Triggers

Just as Keyboard Maestro has lots of groovy actions, it has a crazy array of triggers. We’ve seen keyboard shortcuts and commands on the Keyboard Maestro status menu, but there are 14 other options too. I’m not going to enumerate all of them here—you can read all about them in the Keyboard Maestro documentation—but I want to call out a few that I think are especially noteworthy:

- Typed String Trigger: Unlike a keyboard shortcut, which uses a combination of keys pressed at once (typically with modifiers such as Command, Control, Option, and/or Shift), a typed string trigger is a sequence of keys you type without a modifier. In Automate Text Expansion, we saw how software can turn a typed abbreviation into a longer chunk of text. This is the same idea, except that typing an abbreviation runs a macro (and optionally deletes those characters you just typed). For example, I could type an abbreviation that fills in some predefined text, selects the entire current paragraph, and copies it to the clipboard—all in one operation.

- Time Trigger: Have your macro run on a timer! This trigger lets you select the time and day(s) of the week you want it to run.

- MIDI Trigger: If you have a piano-style MIDI keyboard (or any other MIDI instrument) connected to your Mac, you can trigger a Keyboard Maestro macro when you play a particular note. (Incidentally, there are also MIDI actions to send note on, note off, and control change messages.)

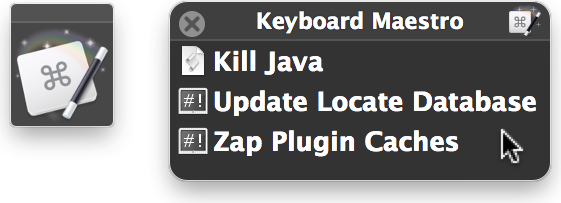

- Macro Palette Trigger: This floating palette normally takes the form of a small icon (which you can position anywhere on your screen), but mouse over it, and it displays a list of macros that you can trigger with a single click (Figure 48).

Figure 48: The macro palette is normally unobtrusive (left), but when you mouse over it, it expands to show macros you can activate with a click (right).

- Wireless Network Trigger: You can trigger a macro by connecting to, or disconnecting from, a certain Wi-Fi network.

Every Minute Counts

I’d like to wrap up this section on Keyboard Maestro by going back to a story I mentioned in the Introduction.

For years, I’ve kept track of my income as a freelance author on a daily basis—it’s the only way I can stay on top of my budget given the ups and downs of the publishing business. It used to be that every single day, I’d check to see how many copies of each of my Take Control books I’d sold the previous day (by counting email receipts). Then I’d check that day’s earnings from Google AdSense and Amazon affiliate links on my Web sites. Finally, I’d enter all this information into a spreadsheet.

That whole process took me about 5 minutes a day, and I couldn’t stand it. After doing this hundreds of times, I finally got fed up and decided I’d figure out once and for all how to automate it. I spent a full day creating an elaborate Keyboard Maestro macro that, in combination with some AppleScript code I’d previously written, did all that for me—all on a recurring schedule, so it now requires zero clicks, zero keystrokes, and zero minutes. I now get to save 5 minutes a day—or 30 hours a year—and I cherish every moment of it.

Use Another Macro Utility

Keyboard Maestro isn’t the only macro utility for OS X, but it’s an excellent one—and it’s the only one (as far as I can tell) that’s receiving active development attention. But, because I know people will ask, I do want to say a few words about other Mac macro utilities:

- iKey: Although not in the same league as Keyboard Maestro, iKey is a fine little macro utility. It has a reasonably thorough list of triggers and actions, and can dispatch many repetitive tasks with ease. (And, it has Take Control cred: Adam Engst wrote Take Control of iKey 2, which is slightly outdated, but still useful.)

iKey doesn’t include logic, as such. For example, it can wait for certain app or window states before moving on with the next step in a macro, but it can’t make if/then/else decisions, process variables, perform loops, search for text patterns, or evaluate complex conditions as Keyboard Maestro can. And its interface is odd—it strikes me as being backwards from the way most macro utilities approach triggers and actions. As I write this, iKey’s last update was on October 31, 2011, which is a long time in Internet years. Although it works (with a bit of coaxing) under Mavericks, it doesn’t appear to be in active development, which makes me reluctant to recommend it.

- QuicKeys: Back in the day (that is, before 2010 or so), QuicKeys was the biggest, baddest, most powerful macro tool for Macs. I absolutely loved it—I found it both easier to use and more flexible than the Keyboard Maestro of that era, and was hard-pressed to come up with any automation task it couldn’t perform. Unfortunately, the company that owns it, Startly Technologies, encountered a series of misfortunes—not the least of which was the unexpected death of the lead QuicKeys developer. As a result, QuicKeys has been in a state of suspended animation.

The software hasn’t been updated since December 17, 2009. For reference, those were the days of 10.6 Snow Leopard; 10.7 Lion came out in July 2011. Although QuicKeys is still for sale and still sort of, mostly works with Mavericks (see extra steps required here), it doesn’t take advantage of any recently added OS X technologies, and has nontrivial bugs. Since it was never updated for Lion, Mountain Lion, or Mavericks, I have to assume the current version (4.0.7) is the last one we’ll ever see. It may work (sort of, mostly) for a long time or it may break with 10.10 Yosemite, but despite its power, I can’t feel good about relying on an app that’s barely on life support. If the app should come back to life, I’ll be more than happy to update this section of the book accordingly!

- Alfred: Alfred, which I discussed in Use a Third-party Launcher, has a feature called workflows that’s available only if you purchase the optional Powerpack. Workflows connect a trigger (such as pressing Alfred’s hot key) and/or an input (such as a keyword or a filter) with an action (such as opening a file or URL, or running a shell script or AppleScript) and an optional output (such as a notification or putting something on the clipboard). So, in a limited sense, those sequences of actions are macro-like. But any logic they contain comes only from the embedded script(s), so Alfred’s main contribution is a way to trigger that behavior.

That’s not to say Alfred workflows aren’t extremely useful—they are. With a few keystrokes in Alfred, you can create a new note or search in Evernote, perform a search on multiple Web sites at once, or open a selected image in a browser instead of Preview. But Alfred workflows are much more limited than Automator workflows, and more limited still than Keyboard Maestro macros.