At the beginning of his novel City of Marvels, Spanish writer Eduardo Mendoza, sketches with a few brush strokes a scientific panorama of Barcelona in the nineteenth century:

[...] Barcelona was always at the forefront of progress. In 1818, the first regular stagecoach service in Spain went into operation between Barcelona and Reus. The first experimental gaslight system was installed in the courtyard of the Palace of La Lonja, housing the Chambers of Commerce, in 1826. In 1836, the first steam-powered motor went into operation [...] Spain’s first railroad was built to link Barcelona and Mataró, dating from 1848. The first electric power station was likewise built in Barcelona, in the year 1873. The gap between Barcelona and the rest of the peninsula was enormous, and the city made an overwhelming impression on the newcomer.2

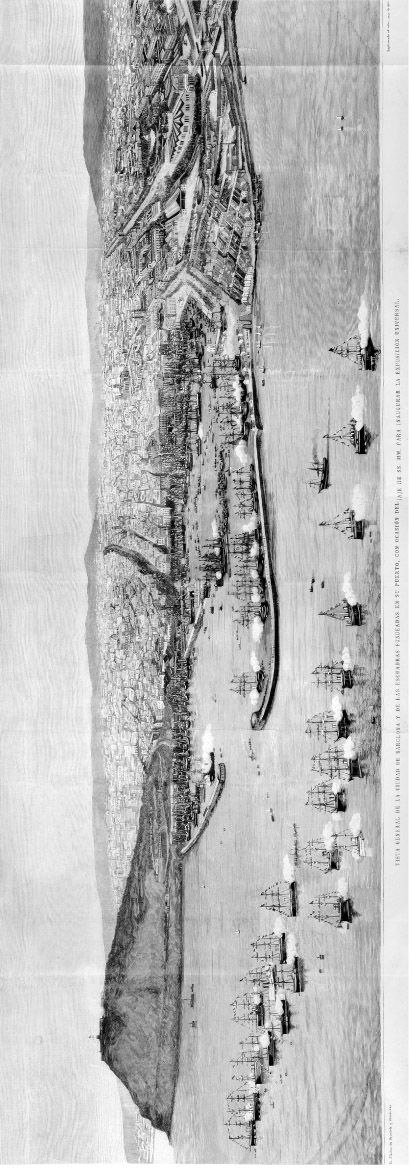

With an image of a city marked by technological innovation and brimming with energy and promise, Mendoza sets the stage for the meteoric career of his protagonist. City of Marvels begins in 1887 when the young Onofre Bouvila, barely a teenager, comes from the Catalan countryside to the bustling city. His first job is to hand out anarchist pamphlets to workers in the Parc de la Ciutadella, the site of the first Universal Exhibition in Barcelona to be celebrated the following year. As the story unfolds, Onofre rises from abject poverty to power and wealth propelled by his relentless criminal energy. Mendoza’s novel ends in May 1929 on the very day the second major exhibition, the International Exhibition, opens this time located on the other side of town, at the foot of Montjuïc. In a spectacular ascent, Onofre rises vertically into the air with a seemingly miraculous machine, leaving the masses speechless only to disappear into the Mediterranean Sea. He had urged a Catalan inventor and a German engineer to collaborate in order to develop this flying contraption. The machine has roughly the shape of a helicopter – the dernier cri of aeronautic technology at the time. Yet it lacks a propeller – a ‘wonder’ as Mendoza writes, tongue in cheek.

City of Marvels, first published in Spanish in 1986, was written amidst the great expectations created by the Olympic Games which Barcelona was to host in 1992. Once again, we might say, the city was eager to catch up with ‘modernity’ as it had done a century earlier, casting off the grey vestiges of the oppressive Franco regime (1939–1975). For Mendoza this era between the two international exhibitions in 1888 and 1929 serves as a mirror for his own present. Despite ‘being first’ on so many accounts, the Catalans – their ruling class of bourgeois industrialists – were unable to assume a leading political role in Spain. Instead they were being bamboozled by ‘Madrid’, the Spanish central power, who was reaping the cream of the two exhibitions for the greater glory of Spain. And – couched in the sometimes funny, sometimes bitter sarcasm of his ‘mock historical novel’ – Mendoza sees the same danger lurking on the horizon with the Olympics of 1992 in the making.3

In spite of Mendoza’s gloomy prognosis that a major international event such as the Olympic Games would be high-jacked once more by the Spanish state, Barcelona was able to gain the world’s attention and to maintain it. The Games did not only convert the city into a major tourist destination. Still in the Olympic year of 1992, art critic and journalist Robert Hughes lamented in his acclaimed book Barcelona the lack of international attention for the city and its history.4 Yet more than two decades later, the political and social history of Barcelona in our Mendozian timeframe (1888–1929) and until the end of the Spanish Civil War (1939) is much trodden turf. In those closing years of the nineteenth century and in the first decades of the twentieth century, rapid industrialization, the dramatic changes in the physiognomy of the city (its expansion and the new architecture) and the increasing social unrest with all its violent manifestations have attracted the interest of social historians, urban scholars, historians of architecture and of art, just as Hughes had demanded.5 Barcelona is known for its modernist art (art nouveau) and its architecture. Architects such as Antoni Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner and Josep Puig i Cadafalch and painters such as Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso and Antoni Tàpies are nowadays crucial for the marketing of the city.6 More than that, historians from near and far have discovered Barcelona, from among other labels, as the ‘world capital of anarchism’ in the first third of the twentieth century as an intriguing object of investigation.7 Yet in our perception this thriving research on fin-de-siècle Barcelona is incomplete. This ever-increasing amount of scholarship rarely addresses at all the role of science (as science, technology and medicine) in this epoch.8

What we would like to borrow from City of Marvels is not only the timeframe but also Mendoza’s perceptiveness about the role of science. Nowadays it is a commonplace that the years between 1888 and 1929 were formative in the creation of ‘modern’ Barcelona.9 Yet what Mendoza clearly grasps is that scientific progress was both a driving agent and a tangible result of this process. City of Marvels abounds with references to technological innovation indicating a seemingly successful modernization. These four decades between the two international exhibitions seem to us an ideal historical window to pursue our project on the scientific culture of Barcelona.

At that time, the city was in a permanent state of construction. Between 1888 and 1929, Barcelona, the ‘Catalan Manchester’, as it was often referred to, grew substantially, to roughly one million inhabitants. Industrial growth demanded a new labour force and shaped its urban geography and architecture with new transport networks and infrastructures. The second industrial revolution brought electricity and chemistry to the already powerful textile industry run by steam. A substantial cluster of textile factories grew in highly industrialized areas such as Poble Nou, but also in the surrounding towns such as Sant Martí de Provençals and Sant Andreu del Palomar. In the search for cheaper sources of energy, other factories moved to the countryside next to the rivers to profit from hydraulic power. This network of circulation of raw materials, workers and finished products, shaped the scientific culture of Barcelona for decades.10

At the turn of the century, Barcelona’s landscape of scientific institutions also changed dramatically. To name but a few of the most relevant ones: In 1882, the Museu Martorell, the first public museum (dedicated to natural history and related fields) opened in the Parc de la Ciutadella. In 1887, the Laboratori Microbiològic Municipal was founded, not least to fight or even better prevent the recurrent epidemics. The rise of Catalan nationalism at the very end of the nineteenth century led to a host of new institutions. In 1899, the Institució Catalana d’Història Natural was founded, in 1907 the Institut d’Estudis Catalans. The latter was an ambitious project for a new ‘national’ (Catalan) research centre embracing all fields of knowledge.11

Yet the dynamic of the local scientific culture resulted – as in many other cities at the time – from a combination of this ‘official’ or ‘elite’ science with a vibrant ‘public’ or ‘civic’ science.12 Obviously these two kinds of science are often intrinsically connected and hard to separate. In terms of civic science, Barcelona was home to a wide variety of activities and institutions: public lectures, exhibitions, university extension courses, collections of living wild animals, amateur astronomical observations, international conferences on popular but controversial fields such as spiritism, athenaeums and pedagogically highly innovative schools. Yet this thriving scientific culture, which often crossed social barriers, has been largely ignored by recent historiography. This is the raison d’être of this book: to write a new, genuine urban history of science of Barcelona.

The thesis of this book is that the history of Barcelona between 1888 and 1929 cannot be properly understood without accounting for the role of science. So far there have been only some valuable but isolated case studies on the scientific culture of the city.13 Our goal is more than simply to add ‘a bit of history of science’, but to provide a new perspective on the cultural makeup of the city and its attempts at modernization. In fact, we do not intend to write a ‘separate’ history of science in Barcelona around 1900. It would make no sense to neatly disjoin these spheres (art, architecture, science, medicine, politics and so on). They need to be understood as a seamless web with numerous intersections. This is obviously a tremendous historiographical challenge and runs the danger of stating truisms such as ‘everything is connected’. Therefore we need to be more precise: what is lacking is not so much a history of Barcelona that also mentions the history of the municipal natural history museum; or the conflictive reception of Darwinism; or the visit of a foreign luminary such as Albert Einstein.14 What is lacking is an urban history of science of Barcelona. Such a history would have to focus on the specific conditions of knowledge production and circulation in these critical decades around 1900.

Starting in the mid/late nineteenth century, many new institutions, formats, media and technologies enter the urban stage. To name some obvious examples: public museums, urban parks, international exhibitions, electric lighting, private clinics, amusement parks, but also newspapers (only becoming a mass medium in the late nineteenth century) and illustrated journals, evening schools and new places of sociability such as the athenaeum, the cinema and eventually radio. Barcelona’s fin-de-siècle medical doctors, patients and their clinics, public health programmes, anarchist and spiritist circles, amateurs, users, local experts and technological networks formed part of a complex cultural mesh. By means of a selection of actors, sites and scientific practices shaped in this specific urban context, we believe that the overall historical account of the city between 1888 and 1929 can be significantly enriched. Our basic assumption is that the urban space is both: a creator, incubator and facilitator of these practices of knowledge production and circulation but also an object substantially transformed by these practices. As urban scholars have argued, ‘rather than a passive container of institutions and practices, urban space was a complex material and symbolic environment that was shaped by – and that in turn shaped – institutions in historically specific ways’.15

Our attempt to write a new, genuine urban history of science inscribes itself into the recent ‘urban turn’ in the history of science.16 This urban turn is a consequence of a more general trend labelled the ‘spatial turn’.17 The insight that the actual site where knowledge is produced matters has taken centre stage in numerous research projects in the last two or three decades. Historians of science have not only looked at ‘traditional’ sites of knowledge production such as laboratories, observatories and collections (cabinets and museums). They have also shifted their attention to sites such as the field, zoological and botanical gardens, hospitals, churches, princely courts, pubs and coffee houses, libraries, lecture theatres, salons and many more. This spatial turn has also led historians of science to look at ‘sites’ on a larger scale, such as the city, encompassing many of the places above.18

A spatial approach should tell us to what extent the specific urban setting of Barcelona shaped the practices of our actors and led to the emergence of the media and institutions related to science, technology and medicine. And the other way round: in how far these practices changed the urban environment. It is such a dialectical approach that is required in order to analyse the scientific practices in a particular quarter (Barrio Chino or Eixample), in a specific urban public place (the Parc de la Ciutadella, the central Plaça Catalunya or the Tibidabo mountain) and even in the whole of the city. It is of significance whether anarchists met in the quarter of Sants or the spiritists in the quarter of Gràcia. It matters where the amusement parks were located, where the Barcelonese visited museums and the zoo, and where the sick sought medical advice and treatment. In our volume, a detailed look at the myriad of sites will help us to understand the ways in which scientific knowledge was transferred and appropriated by different actors.

In the following 10 chapters of this book, we reconstruct a host of specific sites. When we speak of a site, we usually think of a very concrete physical place than can be located on a map. It has an address and a material existence, such as an academy, an observatory, a laboratory, an athenaeum or a clinic. Yet this ‘localized’ understanding is insufficient to get hold of the scientific culture of Barcelona in its entirety. Many sites might only be occupied for a certain period of time. An anarchist meeting place might only be used for a month or two and be clandestine. The spiritists too might gather in changing venues. In these cases, site becomes a fluid category, part of dynamic urban networks in which people, objects and ideas constantly circulated and contributed to the making of a specific scientific culture.

In fact, the insight that the city, an assembly of so many small-scale sites, is a dynamic arena of scientific practices, and therefore requires and merits a specific perspective dates back a long time. Robert Kargon’s seminal book on nineteenth-century Manchester was first published in 1977.19 Yet it seems to us – as part of the spatial turn in history of science – that the city has acquired increased prominence as an object of research since roughly the turn of the millennium. In 2003, a special volume of Osiris was dedicated to Science and the City. Sven Dierig, Jens Lachmund and Andrew Mendelson suggested investigating the interactions between the city itself and the sites of production and circulation of knowledge. It is precisely at the intersection between urban expertise, cultural representations, places of knowledge and everyday practices that a truly urban history of science can emerge.20

Another important contribution is the edited volume Urban Modernity that came out in 2010.21 Miriam Levin and others focused on the role of social elites (including scientists) in urban growth, international exhibitions and museums. Their case studies were Paris, London, Berlin, Chicago and Tokyo. This is representative for current scholarship on science and the city. So far historians of science have mostly focused on the metropolis. There are, of course, quite a number of individual articles dealing with specific aspects of the scientific culture of smaller cities in this formative period around 1900.22 Yet what are missing – as far as we can see with very few exceptions – are comprehensive and systematic studies. The existing scholarship on smaller cities has left little impact on the overall picture. We need to ask to what extent can results of studies on science in the metropolis be transferred to other urban contexts,23 or whether a different interpretative framework is required to approach places such as Lyon, Marseille, Milan, Hamburg, Glasgow, Budapest, Amsterdam, Copenhagen and Antwerp and, of course, Barcelona. Are there different things to be learned from such supposed ‘second cities’?

To repeat: the general historiography has neglected the scientific culture of Barcelona around 1900. Or rather, scientific practices are taken as givens, amalgamated as ‘scientific and technological progress’, as an explanans and never as an explanandum. And within history of science and the growing scholarship on urban science, cities such as Barcelona have not received distinct and in-depth treatment. As David Livingstone has argued: ‘Bristol science, Manchester science, and Newcastle science are not the same as science in Bristol, science in Manchester, or science in Newcastle. The place-name adjectives in these designations attest to scientific practices that were constituted in different ways and different urban cultures’.24 We shall therefore try to pinpoint the genuine and distinctive features of the urban history of ‘Barcelona science’.

Despite the increased interest of historians of science in the urban history of science, it is our perception that much of this scholarship focused in one way or another on the elites of a given city: on leading scientists and engineers but also on town planners, architects, organizers of exhibitions, promoters of public health services, in short: experts of all sorts. It goes without saying that this focus on scientific elites is indispensable when dealing with science and the city around 1900. Yet this book proposes a different approach, a complementary one and possibly more than that. The ten following chapters assembled here ask how the scientific culture affected and changed the everyday life of the city dweller, how these Barcelonese citizens perceived and appropriated the changes and developments in their urban habitat induced by science, technology and medicine and how they themselves participated in a variety of ways in this new scientific culture.

In this sense this book attempts to combine two burgeoning historiographies, the scholarship on science and the city with the scholarship on popular science. ‘Popular science’, or rather the intricate relationship between science and its publics has proven to be a very fertile field in the understanding of the production of knowledge. To sum up some of the most important insights of this research in a bullet point way: The public of science is not a passive recipient. It actively appropriates knowledge in its own, often idiosyncratic way. It is crucial to stress the diversity and plurality of publics. Science popularization should not be described as a top-down model but rather as ‘knowledge in transit’, as an interactive process between scientists and their audiences. Historians of science now ask how knowledge is communicated, validated or rejected, appropriated or contested and so on in order to explain how a claim may gain acceptance.25

Combining these two historiographies of the urban history of science and of popular science, thus implies identifying the numerous audiences of science in a specific city. In the urban jungle of actors, objects, sites and events, there are lots of micro-histories which deserve further attention. In the same way that historians defend the epistemological value of a particular case study as opposed to big historical narratives, particular episodes in the city might shed new light on the complexities of the urban history of science. We will ask: How do certain scientific practices and technologies change everyday life? But also: how does the latter influence the former?

This quest leads us to the methodological question as to which sources we could use to reconstruct the perception and appropriation of science in the city around 1900. This question has kept a large number of historians of science busy: How to give this variety of publics, the students, the audiences of public talks, the users of technologies, the patients in the clinics and dispensaries, the radio amateurs and the instrument makers, the animal keepers and the technicians their proper voice? Testimonies from these groups are more often than not hard to come by. If they show up at all, they are mostly indirect, presented by a different voice situated on a higher level, an expert, a physician or a university professor. In other words: the historian is confronted with a stark asymmetry in the sources. The ambition of this book is to expand the existing attempts to try and reconstruct these voices, which generally have only a faint or strongly distorted echo in the material available. The contributors of this volume have identified a host of new primary sources such as city guides, medical guides, specialized journals, the archives of publishing houses, local societies and institutions, personal diaries, travel reports, but also reportage, novels, satirical magazines, advertisements as well as photos, caricatures, maps and architectural plans.

This vast range of different practitioners played a crucial role in the struggle for scientific authority and the idiosyncratic appropriation of expert knowledge. Barcelona was the city of mediums, cheap telescopes, radio stations, underground sexual hygiene, electricity users and anarchist notions of health; an urban space in which citizens appropriated scientific culture in complex and varied ways, more or less explicitly, as a strategy, or perhaps simply as a tactic – in Michel de Certeau’s terms – to resist the cultural hegemony of the elite and its science.26

Following this framework, we have organized the case studies of our volume under three different headings: 1. ‘Control – Elite Cultures’ gathers the Parc de la Ciutadella as a paradigmatic place for popular science and its agenda of disciplining (Hochadel & Valls), the political lining of natural history in the public sphere (Aragon & Pardo-Tomás), the new hegemony of laboratory medicine emerging in the Eixample district (Zarzoso & Martínez-Vidal), and the elite’s control of the technology of amusement parks all over the city (Sastre-Juan & Valentines-Álvarez). 2. ‘Resistance – Counter-Hegemonies’ includes anarchist science and its places across the urban fabric (Girón Sierra & Molero-Mesa), spiritist practices and its social impact on the city (Balltondre & Graus), and the underground medical culture of the Barrio Chino (Zarzoso & Pardo-Tomás). 3. ‘Networks – Experts and Amateurs’ shows how technology spread through the city and how professionals, businessmen, but also aficionados and clients interacted. These last three case studies are devoted to the emergence of an ‘urban astronomy’ with its rich amateur culture (Roca-Rosell & Ruiz-Castell), the impact of the radio and its users (Guzmán & Tabernero) and popularization and domestication of electric lighting (Ferran & Nieto-Galan).

Readers, visitors, patients and users of new technologies appropriated what they were told or advised to do in their own way. They question or defy authorities, come up with their own interpretations, build their own devices or apply heterodox medical treatments. They also contribute to the legitimization of new scientific disciplines and specialties (in medicine, urban planning, sanitary reforms, natural history, astronomy and so on) and to the making of scientific authority in the urban public sphere. In what follows, we shall sum up very briefly what these ten chapters might contribute to a better understanding of science and the public in an urban, fin-de-siècle context.

At the very same time the city became a place for social control but also for social critique. On the one hand the major projects and institutions of this new urban culture of science aimed at educating and ‘moralizing’ the masses, and thus controlling them.27 Manifestations of this attempt to achieve cultural hegemony and to exert social control are the two international exhibitions, the public museums, the Parc de la Ciutadella, and even amusement parks. The Junta, the Board of Natural Sciences, transformed the new urban Parc de la Ciutadella into a place for the popularization of natural history. The Junta was caught between the notion of an ideal visitor, well behaved, educated and eager for self-improvement and the bugbear of the ‘real’ visitor, allegedly only interested in amusing himself or worse torturing animals at the zoo or poking at the enormous mammoth made of stone (Hochadel & Valls).

These leanings were also very tangible in the well-documented donations to the first public museum in Barcelona, the Museu Martorell, founded in 1882, which allows us to sketch the astonishing variety of publics. The donors range from the foremost aristocrats and businessmen to travellers, military officers and avid naturalists to the ‘simple’ citizen with no training in natural history finding a fossil on his Sunday stroll on Montjuïc. This sketch also shows the change in the social milieus of the donors in the decades between roughly 1880 and 1920: broadly speaking the ‘cosmopolitan’ aristocrats gave way to middle-class naturalists exploring the natural history of the region. The people of Barcelona knew that the Martorell was the place to bring strangely shaped eggs or a rare mineral. Yet that does not mean that the museum was a ‘democratic’ space. Particularly from 1900 onwards, it was geared towards a middle-class audience with specific ideological leanings: Catholic, conservative and Catalanist (nationalist) (Aragon & Pardo-Tomás).

In our Mendozian timeframe from 1888 to 1929, medical practice also underwent radical changes in Barcelona. It was precisely in the late 1880s that in the new district of the Eixample the first specialized practices (‘clinics’) emerged. The ‘new age’ of laboratory medicine with its host of new instruments and technologies manifested itself in these private clinics and in their specific functional architecture. This movement left the old city and its hospitals behind in a double sense: geographically but also epistemologically distancing itself from the ‘old-fashioned’ university-based medicine of the time. The physicians running these new ‘clinics’ needed to forge a new ‘public’, principally from among the bourgeoisie. They managed to create new demands advertising their ‘modern’ treatments. It was this group of patients that also provided empirical evidence, ‘material’ for scientific publications in these new fields of medical specialties. Thus these new practices shaped the identity of patients but also of the physicians (Zarzoso & Martínez-Vidal).

Technology had a profound impact on the everyday life of the Barcelonese in numerous respects. It also changed the way they spent their leisure time. In the early twentieth century, a number of amusement parks were set up in different parts of the city and outside of it, following a specific social geography. Each one of these parks provided ‘technological fun’ for a specific class of people ranging from the working class to the affluent. While the visitors were screaming in the roller coaster, they were in fact subjected to new regimes of pleasure immersed in an ideology of technological progress (Sastre-Juan & Valentines-Álvarez). Conservative Catalanism and Catholic science were the crucial ingredients of a cultural hegemony established around 1900. As in many other European urban contexts, the bourgeois, industrial city and its cultural hegemony sustained by the ideology of progress were confronted with popular values rooted in republican, working class, socialist and anarchist ideas.

In Barcelona, the ‘divided city’, torn apart by the increasing social conflict, ‘counter-hegemonies’ such as anarchism emerged. They not only promoted their own moral codes but also their understanding of what constitutes scientific knowledge.28 For anarchists science and its popularization served as a mean of emancipation, most notably in their specific reading of Darwin. Anarchists in Barcelona had their own journals and their own meeting places (even if only transient), where they educated themselves. Barcelona was the city of popular athenaeums (ateneus populars), in which workers attended evening schools (including courses on science) after their long working hours. Health-related issues were particularly high on their agenda. (In a sense, bourgeois and anarchist views overlapped in this respect: science served the goal of personal improvement, intellectually and morally). For anarchists, the notion of an ‘expert’ and of authority was by definition problematic. Working-class audiences forcefully questioned the competence of invited speakers, thereby proving how far they had risen in their self-civilizing mission (Girón Sierra & Molero-Mesa).

Barcelona was also home to other associations (republican, freethinkers, masons), which competed with conservative Catholic organizations for cultural hegemony in education and in the public sphere. Starting in 1895, a popular library, the Biblioteca Arús, provided books and journals (including popular science) for the working classes, informed by anarchist, republican and masonic values.29 Yet in the very same year, because of his lectures on Darwinism, the Catholic authorities shut down Odón de Buen’s chair in natural history at the University of Barcelona.30

Spiritists should be understood as a ‘counter-hegemonic’ movement as well, in particular in the Barcelonese form. They too challenged the existing epistemological hegemony and very consciously pursued heterodox practices and beliefs. Just like the anarchists, the spiritists were resolutely anti-Catholic, setting up their own journals, associations and schools in order to implement their social and moral agenda. They even started their own clinic treating a large number of patients with heterodox practices such as hypnosis and magnetism. Women played a central role in the spiritist movement in Barcelona, both as actors (media, authors, public speakers) and as target audience. Despite their complete lack of formal education, female media such as Amalia Domingo were able to become influential figures in Barcelona’s public arena (Balltondre & Graus).

In stark contrast to Eixample, built upon hygienic principles, stands the Barrio Chino. The quarter today known as Raval was marked by poverty, prostitution, the entertainment industry – and medically speaking – by tuberculosis and venereal diseases. For the bourgeoisie, it represented both a symbol of moral decay as well as an irresistible lure. The Barrio Chino was characterized by constant attempts to medicalize its inhabitants. Yet as a close analysis shows, this medicalization went far beyond official attempts to contain the danger the Chino represented to public health. It reveals the plurality of – often self-declared – medical experts constantly manoeuvring between treatment, health (and sexual) education, commerce and entertainment bordering on pornography (Zarzoso & Pardo-Tomás).

In many fields science had not been fully professionalized in Barcelona around 1900. As elsewhere in Spain, amateurs of all sorts played a crucial role. We already mentioned the naturalists of the Museu Martorell. Many of them had no formal training in the natural sciences yet became the leading scholars for example in geology, palaeontology and speleology. A ‘classic’ field for amateurs is astronomy and the scientific culture of Barcelona provides a particularly instructive example. Even celebrated astronomers of international renown such as Josep Comas i Solà were strictly speaking amateurs. The widespread interest of the public and the support of wealthy patrons led to the establishment of well-equipped observatories, the founding of associations, the proliferation of telescopes and other instruments made possible by an increasing number of specialized workshops as well as valuable research in observational astronomy. The Barcelonese astronomers were furthermore highly active in popularizing their own work reaching thus an even larger public (Roca-Rosell & Ruiz-Castell).

Amateur astronomers were able to build communities of their own in the city. In these networks of sociability, they shared skills and exchanged information, objects and instruments in constant tension with institutional science and official expertise. This is similar to the case of early radio users in the 1920s. There was a sizeable community of radio enthusiasts building their own devices and voicing their ideas and concerns in the journal of Radio Barcelona, RMB. In other words, they were asserting their own expertise in the epistemological space they shared – not without friction – with accredited experts. Radio Barcelona itself also became a medium for science popularization. Astronomy and health-related issues were by far the most popular topics of the radio lectures, thus reflecting the scientific culture of the city (Guzmán & Tabernero).

Just like the radio antennas on the rooftops, the spread of electric lighting altered Barcelona’s cityscape and reshaped the everyday life of its citizens. The nocturnal city became a new ‘site’, full of life, overcoming the routines dictated by natural light: from the ‘electric’ night parties at the 1888 Exhibition, to the new facilities at the operating rooms of the clinics (Zarzoso & Martínez-Vidal), and the electrical lights at the fun parks (Sastre-Juan & Valentines-Álvarez). The sophisticated display of lights and colours at the 1929 Exhibition was widely considered a triumph of electricity in the city. Part of this large-scale event was the Exposición de la Luz. This ‘Exhibition of Light’ was a mix of techno-scientific popularization and commercial promotion of the new, electricity-based technologies aimed at the private consumer. New spaces such as showrooms appeared in the city skilfully displaying the virtues of electrical appliances. These initiatives rested on the emerging alliances between companies, engineers, advertisers and designers and created new experts as well as new publics, that is, (mostly female) customers (Ferran & Nieto-Galan).

Despite the evident male hegemony of the urban scientific culture of Barcelona at the time, this is only one example where women contributed in a variety of ways to the circulation of scientific knowledge in public as well as private sites in the city. Women emerge as donors of natural history specimens to public collections (Aragon & Pardo-Tomás), as bourgeois patients in the clinics of Eixample (Zarzoso & Martínez-Vidal), or as prostitutes in the Chino resisting programmes of medicalization (Zarzoso & Pardo-Tomás), as audiences of public lectures of astronomy (Roca-Rosell & Ruiz-Castell), as users of electrical appliances at home (Ferran & Nieto-Galan), as spiritist media (Balltondre & Graus) or as workers in textile factories.31

To be sure, much of the evidence cited in theses cases is indirect and remains fragmentary if not distorted. One may even mockingly say that our knowledge, no, our ignorance of ‘the public’, is made even more obvious by these approaches which leave so many questions unanswered. Yet that would be a mistake. Clearly acknowledging the large holes, which remain with respect to the publics of science, these methodologically varied attempts help us to paint a far richer and more interesting picture of the discursive processes in the scientific culture of Barcelona around 1900.

Urban planner Peter Hall’s optimistic understanding of cities as innovative milieus, as ideal contexts for overcoming cultural inertia and stimulating creativity will probably always be counterbalanced by historian of technology Lewis Mumford’s vintage but still powerful vision of cities as inevitable sources of environmental degradation, social division and even cultural barbarism.32 In a sense, these antagonistic visions of the modern city were already formulated in our Mendozian timeframe in the decades before and after 1900. Just like in any other city, our historic actors in Barcelona put forward both highly optimistic and sceptical views. Political and economic elites appropriated international exhibitions in order to legitimize their own interests. Technophilic discourses radiating with optimism celebrated the city as a paradigmatic space of modernity.33 Railways, tramways, electric lighting, radio, sewage, power stations and public health campaigns established new ways of expertise and public trust in science, and changed dramatically the everyday life of normal citizens. Miriam Levin has recently stressed for example how institutions and social elites shaped city life in Paris with urban plans to legitimize discourses of linear progress.34 Similarly Sophie Forgan has examined the way in which urban elites shaped London’s life and culture, being full of enthusiasm for technological modernity.35 Nevertheless, resistance against and criticism of the ‘modern’ city was also frequent, taking different forms in different local contexts. The technological progress and the rise of new expertise was apparently inevitably accompanied by the danger of pauperism, moral decadence, prostitution, epidemics, poor housing, noisy factories and never ending social conflicts.36 In fact, as Mikael Hård and Markus Stippak have pointed out, different social groups construct diverging images of the city, in which modernity as a universal concept becomes complex, varied and never homogeneous. From a politically conservative point of view, the city seems to be a dangerous place, full of social unrest and political struggles, in contrast to the ‘stable’ countryside. It appears to be a site of degeneration and decadence, simply a repulsive place. But from a more progressive, liberal position, the late nineteenth-century industrial city soon became a paradigmatic place for social reforms (schools, public services, social housing, traffic systems, water works), innovation, creativity and amusement.37

In Barcelona, in the period under study, debates on the meaning of modernity, linked the scientific practices intimately with the city in a variety of ways. If we take for instance special events such as the 1888 and 1929 international exhibitions, it is easy to see how conservative elites were in general in favour of and even enthusiastic about the projects. By contrast, members of the liberal middle class expressed more reluctance, while the working class organizations were often the most critical.38 At the 1888 Exhibition, elite discourses on the supposed benefits of the public were counterbalanced on different fronts.39 Dissenting voices such as the writer and journalist Josep Yxart (1852–1895) very much doubted the alleged modernity of the project. He gave a long list of reasons: the local and national economic crisis that the city was suffering at the time; the industrial weakness of the nation; the proximity in time to the 1889 Paris Exhibition; but also the lack of experience in organizing such an ambitious event; the lack of a reliable urban transport and communication network, together with the decay of the old town and its difficult renewal.40 Equally, the workers’, socialist and anarchist associations denounced the supposed modernity of the exhibition as a ‘bourgeois’ display of luxury goods and waste, and criticized the false rhetoric of peace, the commodification of knowledge and the corruption of the prize juries.41 At the International Exhibition of 1929, for instance, Jorba, one of the city’s most popular department stores, organized a public display on the ‘progress of the city’ in its own pavilion. A comparison between the way of living in 1888, at the time of the first international exhibition, and that of 1929 showed the proper path towards progress and modernity: education, public transport, housing, labour conditions, business and trade, all seemed to have achieved a new stage of ‘modernity’.42

The chapters of this book are replete with examples of how the discourses of the elites shaped their own idea of modernity: there is the policy of medicalization, that is, the projects of hygiene and public health in socially desolate areas such as the Barrio Chino; the emergence of new medical specialities and chirurgical practices; the pursuit of a utilitarian agenda of applied natural history as in the case of Francesc Darder, the founder of the Barcelona Zoo; the vision of the engineers of new electrical grids as agents of social change and irresistible progress, and a kind of ‘mechanical optimism’ as a metaphor for the new industrial order in the amusement parks. In many of these examples, urban growth went hand in hand with what was understood as progress induced by science, technology and medicine.

But modernity also took other genuine forms. Take for instance a group of naturalist-priests at the Seminari de Barcelona who eagerly pursued natural history. Within a framework of biblical temporality, scholars such as Jaume Almera and Norbert Font explored and described ‘Catalan’ nature.43 But this conservative, apparently anti-modern programme was not opposed to the idea of a utilitarian science as a crucial ingredient of industrial progress. Darder and his programme of applied natural history fitted very well into this kind of conservative modernity.

Between 1888 and 1929, Barcelona became a complex technological network in which people, animals, commodities, electrical power and light circulated widely. Animal traction coexisted with electrical tramways and undergrounds and later automobiles. Gas, water, sewage and electricity were progressively extended through neighbourhoods, streets, buildings and apartments.44 Public works became part of the everyday technological culture, not only in the massive transformation of the Parc de la Ciutadella and the Montjuïc area for the two international exhibitions, but also in the building of new railways and streets, such as Via Laietana in the centre of the Gothic quarter. A sort of industrial, machine-like modernity – which included amusement parks located on two symbolic mountains of the city, Tibidabo and Montjuïc – took hold of the city. The spread of electric lighting altered the habits of the everyday life of the Barcelonese. The sophisticated display of lights and colours at the 1929 Exhibition was specifically designed to convince its visitors of the transformative power of electricity and industrial progress. For the urban middle classes, the ‘triumph’ of electric lighting clearly indicated ‘modernity’. When Radio Barcelona started broadcasting in 1924, it also began to shape the everyday life of the Barcelonese – another hallmark of this urban modernity so typical of the 1920s.

But there were other concepts of modernity in Barcelona that often clashed with the above one. We have already mentioned the struggle between hegemonic bourgeois science in its particular Barcelonese form of Catholic and Catalanist conservatism, and the ‘counter-hegemonies’ of republicans, freethinkers and in particular, anarchists but also spiritists. There were republicans such as the Darwinist Odón de Buen and alternative spaces such as Francesc Ferrer’s Escuela Moderna. This educational project was based on different ‘modern’ values such as freethinking, secularism, coeducation and a monistic explanation of the universe. Its aim was to substitute religious worldviews by the new ‘objectivity’ of modern science. Ferrer was executed in October 1909, accused of (intellectually) instigating the riots in Barcelona in late July that year. In the so-called ‘Setmana Tràgica’ (Tragic Week), protesters attacked and burnt down Catholic churches and monasteries across the city. The uprising was brutally struck down.45 In a similar way, spiritist circles campaigned in favour of a new positivist religion, a system of beliefs that challenged the moral authority of the Catholic Church. Spiritists considered their own approach to moral values and religion as ‘modern’.

In the City of Marvels, as in many other western cities, the rhetoric of modernity was also intimately tied to the nineteenth-century building of the modern nation.46 But the case of Barcelona was in many ways peculiar. In the public debates about the pros and cons of the two international exhibitions in 1888 and in 1929, the tension between the conflicting nationalisms – the Spanish and the Catalan one – was very tangible. In the Restoration period (1875–1931), the Spanish liberal state, with its central administrative centre in Madrid was weak. A considerable concentration of industrial urban elites on the periphery, most notably in Barcelona, demanded their share of political influence.47 In addition, from the 1860s onwards, a cultural movement named ‘Renaixença’ sought a ‘rebirth’ of Catalan culture through the recovery of the Catalan language and literature. This movement strived for economic, political and cultural autonomy from Spain. Around 1900 Catalanism also extended to science. Many actors linked pure and applied knowledge to the progress and modernity of the Catalan nation. Scientific Catalanism attempted to shape a scientific culture – including here again science, technology and medicine – in a nationalist sense, using a modern scientific Catalan language and working in an academic context in which research and its applications to industry did not depend on Spanish centralism. Medical doctors, but also engineers and emerging professional scientists, contributed significantly as professional groups to the construction of a Catalan national identity.48 The International Exhibition on Montjuïc had been conceived in a sense as the culmination of this. Yet this project was ‘high-jacked’ – in the view of Eduardo Mendoza and many others – by Primo de Rivera and his coup d’état in 1923 and the subsequent dictatorship.

It is the Spanish king and Primo de Rivera who inaugurate the exhibition in May 1929. And during the opening celebration – at least in the novel City of Marvels – they are spellbound as they watch Onofre Bouvila shooting up into the air with his propeller-less helicopter. Glancing down on Barcelona from the sky Onofre ‘said with emotion, “how beautiful you are! And when I think what it was like when I saw it for the first time! [...] The country began right there, the houses were puny little things, and these teeming suburbs were just villages [...] The future is already my past”’.49 Having said that Onofre crashes into the Mediterranean Sea. The navy rushes out immediately but neither remains of him nor of his miraculous machine are found by its divers or its ‘radar’. Onofre simply disappears. Mendoza even ‘quotes’ the obituaries of several newspapers: ‘“The 1888 World’s Fair marked the beginning of his career, and this fair of ’29 its end”’.50

Already in the perception of many contemporaries, the second exhibition of 1929 marked the end of an epoch. Modernity had firmly settled into Barcelona. Yet what it meant and what it implied was more controversial than ever. The 1930s were marked by a series of political upheavals: the birth of the Second Spanish Republic and the establishment of Catalan autonomy in 1931; the outbreak of the Civil War and the anarchist revolution in Barcelona in July 1936, and finally, in 1939 the fall of Barcelona and the beginning of Franco’s dictatorship. One may well describe these conflicts as a violent clash of different, in fact, incompatible notions of modernity. Yet it seems that the integral part that science and technology played in these antagonistic political ideologies has disappeared from sight just as Onofre Bouvila’s flying contraption vanished into the sea without leaving a trace. This book will attempt to recover the urban culture of science of the City of Marvels.

1We would like to thank in particular Dorothee Brantz and Mitchell G. Ash for numerous helpful suggestions and most valuable advice. We also benefited substantially from constant discussion with all the contributors of this volume.

2Eduardo Mendoza, City of Marvels (London: Collins Harvill, 1990), p. 12 [our emphasis]. Original: La ciudad de los prodigios (Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1986). Mendoza takes some poetic license with respect to historical data.

3Joan Ramon Resina, Barcelona’s Vocation of Modernity. Rise and Decline of an Urban Image (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2008), pp. 182–5.

4Robert Hughes, Barcelona (New York: Vintage Books, 1992).

5See for instance: Pere Hereu et al., Arquitectura i ciutat a l’Exposició Universal de Barcelona de 1888 (Barcelona: UPC, 1988); Edmond Valles, Història gràfica de la Catalunya comtemporània. 3 vols (Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1974–1976); Jordi Casassas, Intel·lectuals, professionals i polítics a la Catalunya contemporània (1850–1920) (Sant Cugat del Vallès: Amelia Romero, 1989); Alexandre Cirici Pellicer, 1900 en Barcelona: modernismo, modern style, art nouveau, jugendstil (Barcelona: La Polígrafa, 1967); Pere Gabriel (ed.), El Noucentisme (Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1996).

6See for instance: Cirici Pellicer, 1900 en Barcelona; Teresa-M. Sala (ed.), Història de la cultura catalana: Barcelona 1900 (Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2007).

7Relevant works in Spanish and Catalan are: Pere Solà, Els ateneus obrers i la cultura popular a Catalunya (1900–1939). L’Ateneu Enciclopèdic Popular (Barcelona: La Magrana, 1978); José Luis Oyón, La quiebra de la ciudad popular: espacio urbano, inmigración y anarquismo en la Barcelona de entreguerras, 1914–1936 (Barcelona: El Serbal, 2008). In English: Angel Smith (ed.), Red Barcelona. Social Protest and Labour Mobilization in the Twentieth Century (London/New York: Routledge, 2002); Chris Ealham, Anarchism and the City: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Barcelona, 1898–1937 (Oakland: AK Press, 2010).

8In the remainder of this introduction, we will only use the term science (scientific) understood in its broadest sense, including technology and medicine: John V. Pickstone, Ways of Knowing. A New History of Science, Technology and Medicine (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000).

9For a textbook-like synthesis, see Alejandro Sánchez (ed.), Barcelona, 1888–1929. Modernidad, ambición y conflictos de una ciudad soñada (Madrid: Alianza, 1994).

10For a history of industrialization on a regional level, see: Norman Pounds, A Historical Geography of Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990). See also Jordi Nadal (ed.), Atlas de la industrialización de España: 1750–2000 (Barcelona: Fundación BBVA, 2003). See also: Horacio Capel (ed.), Las Tres Chimeneas: implantación industrial, cambio tecnológico y transformación de un espacio urbano barcelonés (Barcelona: FECSA, 1994); Mercè Tatjer, ‘La industria en Barcelona (1832–1992)’. Scripta Nova, 10 (2007), http://www.ub.edu/geocrit/sn/sn-218–46.htm (last accessed 26 January 2015); 150 anys d’història de la Maquinista Terrestre i Marítima, S.A. i de MACOSA: de la revolució industrial a la revolució tecnològica (Barcelona: Dos Punts Documentació i Cultura, 2009); Pere Colomer, Barcelona, una capital del fil: Fabra i Coats i el seu model de gestió, 1903–1936 (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2014).

11For a more complete list of scientific institutions, see: Alexandre Galí, Història de les institucions i del moviment cultural a Catalunya, 1900–1936, vol. 16: ‘Acadèmies i Societats científiques’ (Barcelona: Fundació Alexandre Galí, 1986); Antoni Roca-Rosell, ‘Les possibilitats d’una producció científica catalana: entorn de l’acció de la Mancomunitat de Catalunya’, Recerques: història, economia, cultura, 14 (1983): 81–95.

12For the concept of civic science, see Lynn K. Nyhart, Modern Nature: The Rise of the Biological Perspective in Germany (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009).

13There are some ‘city guides’ such as Xavier Duran and Mercè Piqueras, Passejades per la Barcelona científica. 2nd ed. (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2003), which deal in a very general way with the history of science in Barcelona. For explicit historical scholarship, see: Matiana González-Silva and Néstor Herran, ‘Ideology, elitism and social commitment: alternative images of science in two fin de siècle Barcelona newspapers’, Centaurus, 51 (2) (2009): 97–115. For the physical sciences, see the paper by Antoni Roca-Rosell and Xavier Roqué, ‘Physical Science in Barcelona’, Physics in Perspective, 15 (4) (2013): 470–98.

14For the natural history museum (the Museu Martorell), see: Alicia Masriera (ed.), El Museu Martorell, 125 anys de Ciències Naturals (1878–2003), vol. 3 (Barcelona: Monografies del Museu de Ciències Naturals, 2006) – and Chapter 3 in this volume; for the reception of Darwinism, see Agustí Camós, ‘Darwin in Catalunya. From Catholic Intransigence to the Marketing of Darwin’s Image’, in The Reception of Charles Darwin in Europe, edited by Eve-Marie Engels and Thomas F. Glick (London/New York: Continuum, 2008), 400–12; for Einstein’s visit to Barcelona, see: Thomas Glick, Einstein in Spain. Relativity and the Recovery of Science (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), pp. 112–19; see also: Roca-Rosell, Roqué, ‘Physical Science in Barcelona’.

15Sven Dierig, Jens Lachmund and J. Andrew Mendelson, ‘Introduction: Toward an Urban History of Science’, Osiris, 18 (2003): 1–19, p. 5.

16For a helpful review of the existing scholarship, see Martina Hessler, ‘Technopoles and Metropolises: Science, Technology and the City. A Literature Overview’, in Mikael Hård and Thomas J. Misa (eds), The Urban Machine. Recent Literature on European Cities in the 20th Century, A ‘Tensions of Europe’ electronic publication (July 2003) (www.tc.umn.edu/~tmisa/toe20/urban-machine), 57–82. Dorothee Brantz discusses the (all too tentative) connections between urban history, environmental history and the history of science in ‘The Natural Space of Modernity: A Transatlantic Perspective on (Urban) Environmental History’, in Ursula Lehmkuhl and Hermann Wellenreuther (eds), The Historian’s Nature: Comparative Approaches to Environmental History (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2007), 195–225; and in ‘The Urban Discovery of Nature: Science, Zoos, and Natural History Museums’, paper presented at the Third Watson Seminar on the Material and Visual History of Science ‘How to write an urban history of science. New approaches and case studies’, Barcelona, 6 June 2014.

17To name but two of the most important contributions to the spatial turn: Jon Agar and Crosbie Smith, Making Space for Science: Territorial Themes in the Shaping of Knowledge (London: Macmillan, 1998); David N. Livingstone, Putting Science in its Place: Geographies of Scientific Knowledge (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003).

18Charles W. J. Withers and David N. Livingstone, ‘Thinking Geographically about Nineteenth-Century Science’, in Charles W. J. Withers and David N. Livingstone (eds), Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), 1–19; Diarmid A. Finnegan, ‘The spatial turn: Geographical approaches in the history of science’, Journal of the History of Biology, 41 (2) (2008): 369–88, in particular pp. 374–8.

19Robert Kargon, Science in Victorian Manchester: Enterprise and Expertise (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977) (new edition, Piscataway: Transaction Publishers, 2009). Roy Porter, London, a Social History (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1994), is another example.

20They distinguish four main interconnections, co-productions between science and the city: (1) The intersection between scientists and politicians gave rise to what was known as urban expertise; (2) Science played a crucial role in the cultural representation of the city: new literary genres (science-fiction and so on), daily papers, photography, films, marketing; scientific activities were deeply embedded in the social and material infrastructures of the city; (3) that is to say specific places of knowledge can only be properly understood through their role within the urban context; (4) There was a significant level of interaction between science and urban everyday life. Dierig, Lachmund and Mendelson, ‘Introduction’.

21Miriam Levin, Sophie Forgan, Martina Hessler, Robert Kargon and Morris Low, Urban Modernity. Cultural Innovation in the Second Industrial Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2010).

22For nineteenth-century ‘peripheral’ cities such as Madrid and Lisbon, see: Tiago Saraiva, Ciencia y ciudad. Madrid y Lisboa, 1851–1900 (Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid, 2005); Antonio Lafuente and Tiago Saraiva, ‘The urban scale of science and the enlargement of Madrid (1851–1936)’, Social Studies of Science, 34 (4) (2004): 531–69.

23Maiken Umbach used the concept of ‘second cities’ in order to advance a comparative perspective within history (not within history of science): Maiken Umbach, ‘A Tale of second cities: Autonomy, culture, and the law in Hamburg and Barcelona in the late nineteenth century’, The American Historical Review, 110 (3) (2005): 659–92.

24Livingstone, Putting Science, p. 108.

25James A. Secord, ‘Knowledge in Transit’, Isis, 95 (4) (2004): 654–72. For a revision of ‘popular science’ as a historiographical category, see: Isis, 100 (2) (2009), ‘Focus: Historicizing ‘Popular Science’. For a general overview, see Agustí Nieto-Galan, Science in the Public Sphere (London/New York: Routledge, 2016).

26Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life. 2nd ed. (Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2003) (1st French edition, 1980).

27Stephen Jacobson, ‘Interpreting Municipal Celebrations of Nation and Empire: The Barcelona Universal Exhibition of 1888’, in William Whyte and Oliver Zimmer (eds), Nationalism and the Reshaping of Urban Communities in Europe, 1848–1914 (London: MacMillan, 2011), 74–109.

28For an analysis of resistance and counter-hegemonies in history of science, see: Agustí Nieto-Galan, ‘Antonio Gramsci revisited: Historians of science, intellectuals, and the struggle for hegemony’, History of Science, 49 (4) (2011): 453–78.

29Montserrat Comas and Víctor Oliva (eds), Llum entre ombres: 6 biblioteques singulars a la Catalunya contemporània (Vilanova i la Geltrú: Organisme Autònom de Patrimoni Víctor Balaguer, 2011).

30Agustí Nieto-Galan, ‘A Republican natural history in Spain around 1900: Odón de Buen (1863–1945) and his audiences’, Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences, 42 (3) (2012): 159–89.

31Cristina Borderías, ‘Women’s work and household economic strategies in industrializing Catalonia’, Social History, 29 (3): 2004, 373–83.

32See Peter Hall, Cities in Civilization (New York: Pantheon, 1998) and Lewis Mumford, The City in History (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1961)

33Mikael Hård and Markus Stippak, ‘Discourses on the modern city and urban technology, 1850–2000. A review of recent literature’, in Hård and Misa, The Urban Machine, 35–56.

34Miriam Levin, ‘Dynamic Triad: City, Exposition and Museum in Industrial Society’, in Urban Modernity, 1–12, pp. 11–12.

35Sophie Forgan, ‘From Modern Babylon to White City: Science, Technology and Urban Change in London, 1870–1914’, in Urban Modernity, 75–132.

36Hård and Stippak, ‘Discourses’, p. 36. See also: Clifford Geertz, Local Knowledge (New York: Basic Books, 1983); Bruno Latour, Nous n’avons jamais été modernes. Essai d’anthropologie symétrique (Paris: La Découverte/Poche, 1997).

37Hård and Stippak, ‘Discourses’, p. 44.

38Agustí Nieto-Galan, ‘Scientific “marvels” in the public sphere: Barcelona and its 1888 International Exhibition’, HoST – Journal of History of Science and Technology, 6 (2012): 33–63.

39Jacobson, ‘Interpreting Municipal Celebrations’. For the plurality of voices surrounding the first world exhibition in London, see: Louise Purbrick (ed.), The Great Exhibition of 1851. New Interdisciplinary Essays (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001).

40Joseph Yxart, ‘La exposición por fuera’, in Ateneu Barcelonés, Conferencias públicas relativas a la Exposición Universal de Barcelona, (Barcelona: Busquets y Vidal, 1889) 117–42, p. 123.

41El Productor, Periódico Socialista, 20 April 1888, 4 May 1888, 14 December 1888; see Nieto-Galan, ‘Scientific “marvels”’, p. 45.

42Las Noticias, 19 May 1929, Suplemento: Barcelona y sus exposiciones, 1888–1929.

43Jordi Bohigas, ‘Per Deú i per la Ciència’. L’Església i la Ciència a la Catalunya de la Restauració (1874–1923) (PhD thesis, Universitat de Girona, 2011). Santos Casado, Naturaleza Patria. Ciencia y sentimiento de la naturaleza en la España del regeneracionismo (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 2012), p. 195.

44Mercedes Arroyo, La industria del gas en Barcelona (1841–1933): innovación tecnológica, territorio urbano y conflicto de intereses (Barcelona: El Serbal, 1996); Joan Carles Alayo, L’Electricitat a Catalunya: de 1875 a 1935 (Lleida: Pagès, 2007). On the industrial vitality of the city see, Mercè Tatjer: Barcelona. Ciutat de fàbriques (Barcelona: Albertí, 2014).

45For an overview see: Joan Connelly Ullman, The Tragic Week: A Study of Anticlericalism in Spain, 1875–1912 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1968); Jordi de Cambra Bassols, Anarquismo y positivismo: el caso Ferrer (Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 1981); Pere Voltes Bou, La Semana trágica (Madrid: Espasa Calpe, 1995).

46On the topic of science and nationalism, see: Carol E. Harrison and Ann Johnson (eds), National Identity. The Role of Science and Technology. Osiris, 24 (2009).

47Joan-Lluís Marfany, La cultura del catalanisme: el nacionalisme català en els seus inicis (Barcelona: Empúries,1995); Josep Termes, (Nou) resum d‘història del catalanisme (Barcelona: Base, 2009).

48For a more specific definition of ‘Medical Catalanism’, see: Enrique Perdiguero, José Pardo-Tomás and Àlvar Martínez-Vidal, ‘Physicians as a public for the popularisation of medicine in interwar Catalonia: The Monografies Mèdiques series’, in Faidra Papanelopoulou, Agustí Nieto-Galan and Enrique Perdiguero (eds), Popularizing Science and Technology in the European Periphery (Aldershot: Ashgate 2009), 195–217. For a definition of ‘Technological Catalanism’, see for instance: Jaume Valentines, Tecnocràcia i catalanisme tècnic a Catalunya als anys 1930: els enginyers industrials, de l’organització del taller a la racionalització de l’estat (PhD thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2012); Antoni Roca-Rosell and Vicent Salavert, ‘Nacionalisme i ciència als Països Catalans durant la Restauració’, Afers, 18 (46) (2003): 549–63.

49Mendoza, City of Marvels, pp. 414–15.

50Ibid., pp. 415–16, quote p. 416. Once more Mendoza takes some poetic license here: The radar was, of course, invented later.