On 12 December 1907 the reproduction of a life-sized mammoth was inaugurated with great fanfare in the Parc de la Ciutadella just north of the city centre.2 The prehistoric beast was made of armoured concrete, at the time a brand-new construction material. Yet for its makers, conservative Catholic naturalists, the creature with the enormous tusks represented a species that was lost through the biblical flood and could thus be read as an anti-evolutionary statement. At the same time the naturalists emphasized that it was a ‘Catalan’ mammoth, representing all the fragmentary mammoth fossils found in Catalonia since 1883. The massive sculpture standing over six metres tall was supposed to educate but maybe even more to impress. Yet its makers were afraid that the visitors to the Parc might climb on the mammoth (or worse) and therefore made sure to keep them at bay by erecting a fence around it.

Between 1872 and 1917 the Parc de la Ciutadella was transformed into a space for popularizing natural history. Its agenda was informed by a set of ideologies that were neither homogenous nor static. The mammoth embodies this peculiar mix of ideas: the construction of a ‘Catalan’ nature in tune with the rising political Catalanism of the time; a Catholic and concordist approach to science, insisting on the compatibility of revealed religion and natural history; the modernization of the country by popularizing the natural sciences in combining instruction and entertainment.

Other elements of the Parc such as the Museo Zootécnico, the Zoological Garden and its Fish Laboratory were characterized by an instrumental understanding of nature. Nature was to be exploited and more than that, to be actively transformed through specific animal technologies for the benefit of the economy and thus society as a whole.

Recent historiography on nineteenth and early twentieth century science frequently uses the word ‘civic’, as in ‘civic science’ or ‘civic pride’. Looking at institutions such as the natural history museum, the zoological gardens and associations of naturalists, these studies emphasize the involvement of interested, committed and often highly skilled citizens in the construction of an urban culture of natural history – largely outside universities and academies of science.3

With our Barcelonese case study we would like to build on this research. We entitled this chapter ‘Civic Nature’ in order to focus on the different uses and understandings of nature. Nature was civic in a triple sense: 1. Educational: The Parc with all its different features was supposed to civilize its visitors, that is, not only teach them natural history but also educate them to be better citizens. 2. Patriotic: At the same time many of the naturalists active in the Parc pursued a nationalist programme eager to present (read: construct) ‘Catalan’ nature. 3. Economic: Much of the Parc agenda is marked by a distinctly utilitarian way of doing science that may best be summed up in the formula of applied natural history. While the Barcelona Parc was highly typical of its time with respect to its civilizing mission, the admixture of nationalism and an explicit economic objective point to a peculiar blend of ideologies. In order to fully understand this ‘civic nature’, we will have to situate the Parc in its broader historical context.

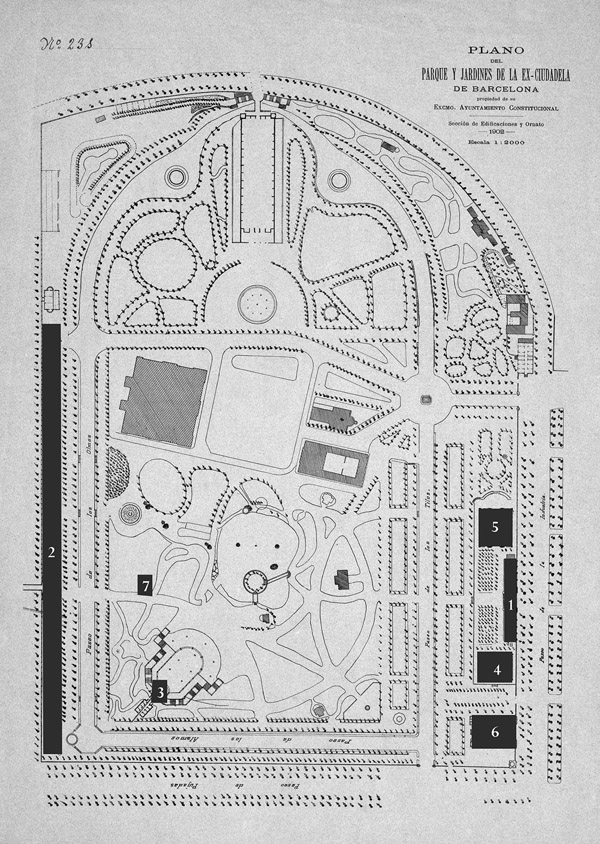

This chapter will therefore first describe the emergence of the public park in the nineteenth century, a prime site for science popularization – and for disciplining its visitors. We will then zoom in on the Parc de la Ciutadella. Among the numerous institutions founded and activities launched between 1872 and 1917 (see Figure 2.1), we will look at three in greater detail: the zoological garden and its acclimatization programme; the nationalist appropriation of the mammoth and of a geological open-air exhibit of stone samples; and finally the activities aimed at the breeding of fish such as the Festa del Peix and the exhibition on pisciculture.4

In many respects the Parc and its ideological underpinnings are typical for the second half of the nineteenth century. In numerous cities, municipal authorities pursued a policy of urban renewal – the ‘greening’ of the city – to counter the effects of industrialization.5 The rapid growth in population of urban centres, the disappearance of commons and the private character of existing parks made it increasingly difficult for the average city dweller to have any access to nature. This situation alarmed reformists and governments because – as they saw it – workers in particular would spend their leisure time engaged in morally reproachable activities such as gambling and drinking. Public parks, free of charge, were supposed to provide a social remedy. And more than that: for the hygiene movement of the time and its demands for a healthier environment in cities struggling with tuberculosis and the occasional outbreak of cholera, the public park was also a medical remedy.6

The new public parks came with a specific socio-political programme: ‘recreation should be associated with improvement’.7 In a time of growing social tensions in increasingly industrialized urban centres, a policy was formulated which argued for the social control of the working classes by means of ‘civilized’ entertainment and recreation, which the public park could provide. The idea was to provide a ‘class-free’ space, yet conflicts about proper conduct and ‘appropriate’ activities were rather the norm.8 As Hazel Conway observes: ‘Some saw parks as places where the classes could mix, but on middle- and ruling-class terms – “gentility mongering places”’. And later she writes: ‘Parks were one manifestation of the rise of modern institutions to control the physical and social processes of urbanisation [...] recreation was increasingly controlled by commercial or local authorities’.9

Recreation in the urban green may come in different forms, for example, walking, sports, rowing on artificial lakes or concerts. Within this agenda to regulate the behaviour of the public and to educate it, science, or rather the popularization of science, played a pivotal role. More often than not a major public park would also be home to one or several of the three main ‘popular’ scientific institutions at the time: the natural history museum, the zoological garden and the botanical garden. And quite often a major park provided the venue for an international exhibition.

In Vienna, for example, the Schönbrunn Park hosts to the present day, the Schönbrunn Menagerie (founded in 1752, open to the public since 1778) and the Botanische Garten, until 1918 both property of the Austrian Emperor. In Paris, all three institutions (Muséum d’Histoire naturelle, Ménagerie and Jardin des Plantes) are still assembled within one park in the centre of the city (dating back to the late eighteenth century). In Dublin the zoo (opened in 1831) is still situated in the ample Phoenix Park, also the venue of the 1907 International Exhibition. The Central Park in New York (inaugurated in 1873) had a small zoo (already opened in 1864), while the American Museum of Natural History is right at the side of Central Park (opened in 1877). The Barcelonese case fits this pattern very well. Hence science, or in more concrete terms natural history, was nearly always part of the educational agenda of any major public park from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. Yet as we shall see, the Parc in Barcelona is remarkable due to the sheer mass and density of institutions and activities pursuing natural history and its popularization.

In 1872, Barcelona City Council approved a plan to turn the site of the former military citadel just outside the city walls into a public park. The fortress – demolished in 1868 – had been for nearly a century and a half a symbol of ‘Bourbon oppression’ (read: the Spanish monarchy and the central government of Madrid) of the city. After the legal handover of the terrain in 1869, the master-builder Josep Fontserè (1829–1897) won the call for tenders advertised by the city.10 The intention was to offer a space for learning, leisure and rest for – at least in theory – all citizens. Yet for Fontserè, just like for most proponents of parks prior to the 1880s, the crucial ‘target group’ was adult males. Men were considered as more likely to have their health impaired in the city due to the strain of professional life in business, factories and public life.11

Fontserè’s scheme, that is, the elements he had in mind for the Parc, was eclectic. His concept of nature as it materialized in the Parc oscillated between the romantic and the utilitarian and instructive. The first architectural landmark to be built was the enormous Cascada in the northern corner of the Parc, started in 1875 and inaugurated in 1881. The cascade hosted a grotto with picturesque arches as entries, the walls and ceilings were marked by sprawling rock formations. A nearby artificial lake with an island completed this romantic part of the Parc enabling the visitor to experience ‘real nature’. Yet from the very beginning, the Parc was also supposed to provide a space for study, instruction and the development of industry. Fontserè’s plan included sites for storing seeds, greenhouses in order to grow specific botanical specimens, a school, a museum of botany as well as a cabinet of mineralogy and zoology and a zoological garden.12 In 1882, the Museu Martorell was inaugurated in the Parc, the first public museum in Barcelona, devoted to natural history and archaeology.13

The coexistence of two concepts of nature, romantic and utilitarian, in Fontserè’s plan may be typical of the time, at least in Catalonia. Roughly speaking, the romantic notion of nature is predominant in the middle of the nineteenth century and wanes towards the end of the century while the utilitarian notion is clearly on the rise at that stage.

In 1888 the city of Barcelona hosted the Exposición Universal in the grounds of the Parc.14 This major event changed the face of the Parc by adding new architectural elements such as the Umbracle, the Hivernacle (both for plants, a ‘shade-house’ and a greenhouse) and the Café-Restaurant, known as the Castell dels Tres Dragons.

In order to manage and extend the facilities of the Parc devoted to natural history, the City Council created in 1893 the ‘Junta técnica de los Museos de Ciencias Naturales, Parque Zoológico y Jardín Botánico’. It is telling that this Junta (henceforth Junta técnica) actually bore the trinity of ‘popular science park’ (natural history museum, zoo, botanical garden) in its name. The Junta técnica was made up of representatives from the City Council and various scientific institutions in the city, such as the University, the Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona and the Institut Agrícola Català de Sant Isidre. As we shall see, an important member of this Junta técnica was the poly-faceted Barcelonese naturalist, Francesc Darder (1851–1918), the founding director of the zoo. His lifelong credo was to develop and exploit the economic opportunities provided by animals of all sorts. Yet the Junta técnica had little leeway not least because of financial restrictions. This changed in 1906 with the creation of the Junta Autònoma de Ciències Naturals (henceforth simply referred to as Junta), which replaced the Junta técnica. The new Junta reflected the rise of political Catalanism and marked a turning point in the agenda setting for the Parc with its special emphasis on the natural history of Catalonia and thus national identity.15

In his prosopographical studies of the Barcelonese naturalists of the first decade of the twentieth century, Ferran Aragon identified a closely-knit network of Catholic and Catalanist scientists.16 These like-minded scholars, among them the priest Norbert Font (1874–1910), the canon Jaume Almera (1845–1919) and Artur Bofill (1846–1929), the director of the Museu Martorell, also dominated the new Junta. The ideological leanings of this Junta (in its majority, not in its entirety) were Catalanist, conservative and Catholic. Their conservative convictions rested on a conciliatory understanding of science and Catholic faith as being perfectly compatible with each other. It was the geologist Norbert Font, disciple of Almera, who formulated the programme of the new Junta. In this agenda he proposed to convert the Parc into a ‘veritable park of culture’.17 In what follows we shall outline the different institutions promoted by the Junta técnica and later on by the Junta. The question is what concept of civic nature drove their initiatives?

Fontserè’s project already toyed with the idea of building a ‘casa de fieras’ (a house for the beasts).18 Yet for most of the 1870s and 1880s, there were mainly cows roaming the greens. In the late 1880s the city already used the Parc as a ‘parking space’ for exotic animals. Live gifts from foreign politicians and businessmen such as caimans, crocodiles and pheasants were deposited there. In 1886, Francesc Darder demanded that the Parc be reformed in order to provide more attractions than merely the ‘monotonous vegetation’.19 Darder had started to work as a taxidermist in the Museu Martorell in 1883, that is, he was well familiar with the Parc. What he had in mind was a zoological garden. And indeed, on 24 September 1892 the Parque zoológico de aclimatación y naturalización was inaugurated on the far side of the Parc.

Darder became the first director and the name of the zoo reflected his objectives. The idea to acclimatize economically useful species from different climates to the European one was thriving in the mid-nineteenth century, in particular in France.20 Exotic animals were supposed to supply meat, eggs, wool and feathers as well as traction force to national economies. Yet already by 1870, this movement had lost its momentum because it had largely failed to be economically viable and had gone out of fashion as a research programme, at least in Europe.21 There had been a Spanish variant of the ‘acclimatization movement’ spearheaded by Mariano de la Paz Graells that was closely associated with the French one. Yet its institutional base was feeble, the acclimatization zoo that Graells founded in 1858 in the grounds of the Jardín Botánico of Madrid had to close down after the revolution of 1868 with virtually nothing to show for in terms of successful and profitable acclimatization.22

Therefore it may appear as an historical oddity to found an acclimatization zoo as late as 1892. Yet upon closer inspection, there is a clear connection. Darder saw himself explicitly in the tradition of the French acclimatizers and of Graells. In 1865 the Barcelonese banker Lluís Martí-Codolar started his collection of exotic animals on a private estate in Horta, at the time still outside the borders of the city. Already from the early 1870s, Darder was acting as an advisor to Martí-Codolar, taking care of the animals and purchasing new ones. Eventually this very collection of roughly 160 animals became the nucleus of the municipal zoo when financial difficulties led Martí-Codolar to sell it to the city of Barcelona in the spring of 1892.23 Darder’s particular focus was on poultry but he also advocated the acclimatization and breeding of camels and llamas. During the first two decades of its existence, the Barcelona zoo held regular sales and auctions. One could purchase animals (dogs, wild boar, goats) and in particular birds (poultry, pheasants, ducks, pigeons) as well as fertilized eggs.

Unlike most other late nineteenth-century zoological gardens, the Barcelona zoo did not charge an entry fee until the end of the 1920s.24 Because the subsidies of the City Council were insufficient to cover the running costs, Darder resorted to the sale of animals and their products.25 This was not atypical for the time. The zoo of Antwerp was particularly business-minded and became a centre for the international trade in animals in the later part of the nineteenth century. In a few years it was able to finance half of its budget through the sale of animals. The Jardin d’acclimatation in Paris, the Schönbrunn Menagerie (Vienna) and other zoos sold surplus animals as well as feathers, eggs and even excrements to anybody willing to pay the money.26

In contrast to these major European zoos, the Barcelona zoo was very small, only covering about two hectares of the grounds of the Parc (today it covers 13 hectares, that is, almost half the surface of the Parc).27 The Barcelonese loved the elephant Avi (see Figure 2.2) but all in all there were few spectacular animals (read: large quadrupeds). In 1912, in his 600-page volume on the history of the modern zoo, Gustave Loisel dedicates exactly one sentence to the Barcelona zoo, stating that is was ‘of no interest’.28 As the biologist Ramón Turró put it in his obituary of Darder in 1918, people wanted exotic-looking birds, ‘lions, tigers and panthers, who would roar night and day’. According to Turró, Darder disappointed the expectations of everybody, the general public, the media and the City Council with his practically-minded approach and his shunning of the show.29 Yet this assessment might be overstated. Darder’s call for an applied natural history and the acclimatization of exotic animals certainly did not fall on deaf ears. It is echoed, for example, in a report of the Junta técnica presented to the City Council in 1899. Its members once more advocated the development of the scientific facilities of the Parc, mentioning the acclimatization of new species at the zoo and the creation of an aquarium. The target group of these efforts were the workers struggling to make a living. The idea was that they would grow plants and raise useful animals themselves at home in order to obtain cheap and healthy food. The report explicitly states: ‘The acclimatization of domestic animals, whose keeping should be cheap and easy, would help to resolve one of the questions which contemporary society tends to dwell on most’.30 In other words: the aim was to dispel the social tensions created by industrialization and urban poverty. In this sense the Parc and its institutions were conceived of as producers and distributors of both knowledge and actual specimens.

The inauguration of the Museo Zootécnico (Museum of Animal Technologies) in the very same year 1899 illustrates once more how Darder and the Junta técnica conceived of nature as a resource to be exploited economically. The objects, among them stuffed animals, skeletons, fur, feathers and so on originated from the zoo and from Darder’s private collection. There were sections dedicated to comparative anatomy, embryology, hunting and fishing, as well as a library and a reading cabinet. The Museo Zootécnico was supposed to show potential industrial applications of natural history. There is very little information on how these materials were actually exhibited – and even less to indicate how far this collection led to any useful inventions.31

And more generally: There is little evidence that these initiatives advocated by Darder and promoted by the Junta did indeed mitigate the lot of the lower classes. In a more cynical reading one may qualify these attempts as predominantly rhetorical, as a tranquilizer for the anxieties of the bourgeois classes due to the social conflict rampant at the time.

Political Catalanism became the major political force in Barcelona in the general elections of 1901. In November 1905 its party, the Lliga Regionalista – conservative, Catalanist and Catholic – achieved a landslide victory in the municipal elections. As mentioned above, this shift in politics led to the instalment of a new Junta in 1906, now bearing a Catalan name: Junta Autònoma de Ciències Naturals.32 This new Junta was, unlike its predecessor, endowed with a budget of its own – and it had a clear agenda. The sculpture of the mammoth (see Figure 2.3) inaugurated in December 1907 was the first of a series of reproductions of prehistoric large mammals from Catalonia that were to be built all over the Parc. The project was inspired by the dinosaur sculptures exhibited since 1854 in the gardens of the rebuilt Crystal Palace in Sydenham (London).33 The aforementioned naturalists, Jaume Almera and Artur Bofill, had seen these sculptures in 1888, while participating at the Fourth International Geological Congress. They were fascinated by the visual power of these archaic creatures. Their idea to adapt a similar project for the Parc was stalled for 20 years until economic and political conditions allowed for it.

Around 1900 there was a revival of sculpting of three-dimensional life-sized dinosaurs. One of the reasons for this was a new building material. Reinforced concrete made the reconstructions easier and cheaper than 50 years before.34 The 18 life-sized reproductions of mostly dinosaurs made by the sculptor Josef Pallenberg in 1911 for the Zoological Garden of Carl Hagenbeck in Stellingen near Hamburg are a splendid example of this revival.35

Reinforced concrete was introduced into Catalonia in the 1890s and at first its principal use was private (water deposits, laundries, sewers and so on).36 In the 1900s it was deployed in public works such as viaducts, bridges and canalization but still not in the city. The Parc offered a highly visible site to display the astonishing properties of this brand new material. Thus, the Junta gave ‘life’ to an extinct animal using a distinctly modern technique: following a small-scale model of a mammoth made of wood by the sculptor Miquel Dalmau, the company of Claudi Duran, which specialized in works of iron and concrete, produced the life-sized sculpture.

The Junta had specifically chosen to begin with the mammoth because it was also the first species of prehistoric mammal to be unearthed in Catalonia. (As it turned out, it was the only sculpture of the planned series of extinct animals that was actually built.) In 1883, a piece of a tusk of a mammoth was dug up in the quaternary stratum of the river Llobregat. More fossil discoveries were to follow, though no complete mammoth was found.

Nevertheless the Junta presented the sculpture in the Parc as a ‘Catalan’ mammoth, an autochthonous being preserved in the soil of the fatherland and now resurrected. The project of sculptures also included large relief maps representing geological landscapes. With the help of these media, the Junta wanted to show a ‘natural’ origin of Catalonia, clearly distinct from Spain and conceived of by God from the beginning of time.37 Yet apart from this nationalist appropriation of the mammoth, the creature was also presented as an ‘antediluvian animal’. The reconstruction represented a species that belonged to a world that had been lost through the Flood. Although only implicitly, the Junta – in its majority conservative Catholics – did take a stand against the theory of evolution. They situated the mammoth in the framework of biblical temporality. The plan of the Junta to exhibit several sculptures of ‘Catalan’ and ‘antediluvian’ creatures fused a nationalist and a biblical concept of ‘nature’. Despite their extinction in the Flood, animals such as the mammoth retained their national identity.38

At the same time as the installation of the mammoth, the Junta launched another patriotic project in the Parc: the display of 40 large stones from all over the country in front of the Museu Martorell.39 This open-air exhibition included big slabs of limestone, gypsum, basalt, granite, porphyry and slate. Although still in the making, the collection aspired to be a comprehensive catalogue of Catalan geology. The shape of the stone samples was standardized in order to give unity to the collection. They were usually extracted from a quarry and cut into a given size (between 1.5–2 metres by 0.5–0.6 metres). In the Parc they were placed upon pedestals (0.7 metres wide) and exhibited as ‘raw materials’ with a polished side. The blocks were marked with signs informing the visitor of the Parc about the type of stone, the location and its origin. The aim was to show the richness and utility of the geological resources –, that is, of ‘mother nature’ – for the modernization of the country. The project had an explicitly ‘regional’ character and as the Junta boasted, it had no equal elsewhere.40

The petrographic collection grew significantly during the following months. This was a most welcome opportunity for the Junta, which was eager to show the results of its activity. By the end of June 1908, the collection already numbered nearly 100 stone samples. The acquisition of such an extensive collection in such a short time was accomplished with the help of commercial and industrial elites of the Catalan bourgeoisie. The majority of rocks proceeded from different quarries or private lands from all over Catalonia. The industrialist and politician Eusebi Güell (an important patron of Antoni Gaudí), the architect Pere Falqués and the politician Salvador de Samà – known by his noble title Marqués de Marianao – figured among the donors of the petrographic collection. Not surprisingly, building and railroad companies such as the Sociedad de Obras y Construcciones and the Compañía de Ferrocarriles Madrid-Zaragoza-Alicante, also donated several blocks.

The donation of a selected piece of rock to the Museu Martorell not only demonstrated that the donor was a ‘connoisseur’ of the natural world,41 it also bore testimony to his patriotic zeal and commitment to Barcelona and Catalonia.42 The message the Junta wanted to convey was clear: nature was a resource that could be and had to be exploited for the benefit of the country. The donors whose names appeared on the plaques of the blocks knew that only too well.

Unlike the acclimatization of land animals, the introduction of certain species of fish was high on the agenda of naturalists at the end of the nineteenth century. The International Fisheries Exhibition in London in 1883 was a highly visible event in the debate – both scholarly and practical – on what were the proper methods of fish farming.43 The new Junta also took to these ideas. Keeping up an impressive pace, the Aquarium at the top of the Cascada Monumental was inaugurated already on 23 June 1908. The exhibition of seals, acquired from the Netherlands, certainly would have increased the attraction of the new installation.44 The Aquarium was part of the existing zoo and completed the collection of living animals. During the following months, many species of fishes were put in the basins of the Aquarium, the cascade itself and the small lake nearby. This was the starting point of a larger project spearheaded by Darder.

In February 1909, the Laboratori Ictiogènic (Fish Laboratory) was founded on the grounds of the zoo. The breeding programme included both indigenous as well as exotic species, such as the green tench of Russia, the red tench of Mongolia and the Japanese carp ‘Hi-Goi’. The plan was to repopulate the rivers and lakes of Catalonia, which had been severely affected by pollution and overfishing. The species to be introduced were supposed to improve the aquatic resources of the nation by increasing and varying production. The Junta distributed fish and fish eggs produced in the Laboratori free of charge to any Catalan municipality with a river or a lake in its vicinity. To celebrate the introduction of fish into local fresh waters, the town supported by the Junta, organized a popular festivity called Festa del Peix (festival of fish).45

The first town to celebrate such a festival was Banyoles in October 1910, followed by Terrassa and Manresa in 1911, and other Catalan towns until 1915. The Festa included different activities such as popular lectures by Darder and other naturalists, the singing of the Himne del Peix (Hymn of the Fish)46, a fishing contest and a regional exhibition on ‘Pisciculture and Fishery’.

On 20 December 1912, the great ‘Pisciculture and Fishery Exhibition’ was inaugurated in the building known as the Castell dels Tres Dragons in the western corner of the Parc. With this highly visible event, the Junta wanted to publicize the results of repopulating the Catalan fresh waters. Outside the building the visitors could contemplate living animals and objects related to the reproduction and farming of fish. A great variety of different species were put on display in huge aquariums. A laboratory of artificial fertilization proved to be a major attraction.47 Once inaugurated, the exhibition was enriched with an exhibit of aquatic plants and another one showing small mammals typical of the fluvial ecosystems.

Inside the building, objects of a different nature were on display: ‘not how to breed fish, but on the contrary, how to kill them’.48 There was a repertory of all classes of artefacts representative of fishery (nets, rods, traps) as well as instruments related to the ‘fish industry’: impermeable clothes for fishermen, pictures, instruments for research, a small collection of books, hydraulic machines, collections of fluvial fauna and so on. This collection of objects proceeded from more than 30 companies and individuals.

At the same time, a whale was exhibited on the Avenida del Paralelo, the heart of Barcelona’s amusement industry.49 The huge whale had been washed ashore some months earlier on the coast of Sant Feliu de Guíxols. The satiric magazine L’Esquella de la Torratxa poked fun at this coincidence, imagining the escape of the whale from Paralelo to the exhibition in the Parc.50 The joke soon became reality (see Figure 2.4). In March 1913 the organizers of the exhibition acquired the whale in order to display it outside the Castell dels Tres Dragons.51 In the Bar Piscatorio inside the building, seafood such as oysters, caviar, salmon, trout and eel was served.52 Organized events not only included lectures on pisciculture but also popular dances, activities for children and concerts of the municipal band. Thus the exhibition became a success drawing large crowds. In the first three months alone, 50,000 tickets were sold.53 Initially scheduled until 30 June 1913, the exhibition was eventually prolonged until 31 December 1913.

Pisciculture was the auxiliary industry of agriculture most promoted by the Junta. But other ‘cultures’ were also featured in the Parc by means of temporary exhibitions. The first exhibition on sericulture was inaugurated on 6 June 1909 in order to foster the silk industry in Catalonia.54 A professional society called Fomento de la Sericicultura Española had proposed the exhibition, which was staged annually, supported by the Junta, until 1911 and again in 1914.

The Junta expanded its scope by adding new areas and agendas. It went beyond the walls of the Museu Martorell and used the Parc as an extension to the city, attempting to occupy different buildings in the Parc. The celebration of the exhibition on ‘Pisciculture and Fishery’ in the Castell dels Tres Dragons was one such attempt. And there were more to come, once more triggered by political changes. The creation of the ‘Mancomunitat de Catalunya’ in 1914, uniting the four Catalan provinces administratively into a ‘Catalan Commonwealth’ eventually also had an impact on the Parc. In 1916 a new Junta mixta de Ciències Naturals was created as the Joint Board of the Barcelona City Council and the Diputació de Barcelona (the government of the province Barcelona). The Junta mixta incorporated several facilities that were built for the Exposición Universal of 1888 such as the Umbracle, the Hivernacle and the Aquarium into its programme for the promotion of the natural sciences in the Parc. Most importantly, the Castell dels Tres Dragons became the seat of the new Museu de Catalunya de Ciències Naturals in 1917. This marked the completion of the transformation of the Parc de la Ciutadella into a space for popular science as well as for research in natural history very much anchored in the rise of political Catalanism in the early twentieth century.

What can we say about the success of these ‘out-reach’ endeavours? Did the Juntas impact the audience they were aiming at? To what extent did visitors to the Parc assimilate the way nature and science were presented? These are difficult questions whose answers demand a more roundabout route. Due to the limited character of the sources, we are able to say much more about how the different Juntas conceived of the public and how they wanted to educate it.

As mentioned above, the idea behind the creation of the municipal park was to create a space that served as a ‘meeting point for all social classes’, as Darder put it in 1886.55 Hence this idea – or rather this ideal – of social inclusion was current in Barcelona as well. But here, as well as in London or Copenhagen, New York or Buenos Aires, the public park was an institution permeated by bourgeois norms. True, its intended audience encompassed the lower classes as well as the upper and middle classes. But the aim was clearly to immerse them in the values of the latter: civilized behaviour, rational recreation, education, self-improvement and self-discipline.56 What impact did this ‘civic nature’ of the Parc and its bourgeois values have on their target audience?

Even basic information such as visitor numbers is in many cases impossible to obtain. What the sources offer are rather isolated comments such as the following by Darder in early 1886: ‘It is with regret that we observe that for a year, the gardens and parks have been every day less visited with the exception of Thursdays and Sundays’.57 This seemed indeed to be a major flaw in the public park scheme in general. How were the workers to benefit from the educational facilities and the clean air of the urban greens if they had to work six days a week? And how were they supposed to travel across town given that the working-class quarters were mostly not in the proximity of the park?58

Let us review the interaction between the promoters of the Parc agenda and their publics in the three case studies we just expounded, starting with the zoo. As has been shown with respect to the nineteenth-century zoo in general, the principal way to learn anything about the actual behaviour of its visitors is to look at the transgressions of the existing rules and norms – because these violations of regulations generated sources, internal reports and public comments. Scholars have repeatedly argued that one may think of the zoo, or public parks more generally, as institutions for disciplining behaviour. The visitor is supposed to learn how to treat the animals (no poking with umbrellas, no throwing of stones), to keep on the paths and not to litter.59

In the case of the Barcelona zoo, it only took two weeks after its inauguration on 24 September 1892 for the first complaints to be voiced in public. According to newspaper reports, visitors threw lit cigarettes at Avi, the elephant of the zoo, and even a glass bottle to see what the pachyderm would do with it.60 The deaths of some flamingos and a white swan were attributed to deliberate poisoning.61 Complaints about the incessant attempts of visitors to feed animals seem to constitute the ‘eternal’ problem of the zoo.62 No different in Barcelona: Already on 4 October 1892, signs were put up admonishing the public not to feed the animals.63

Yet there was also an alternative to the image of the zoo visitors as in need of instruction and at least potentially deviant troublemakers, an image that is predominantly painted by conservative newspapers such as La Vanguardia and El Diario de Barcelona.64 On the pages of the republican and anticlerical El Diluvio, we encounter a public that is active and attentive, demands its ‘rights’ and does behave properly when it visits the zoo and the Parc.65 It does not seem farfetched to hear echoes of the debate about male suffrage, introduced in Spain the previous year in 1891. Should the ‘masses’ be kept in check or should ‘public opinion’ prevail? And instead of casting a critical eye on the general public, El Diluvio asks for explanations regarding the cost of the animals and the management of Darder as director of the newly inaugurated zoo.66

Turning to our second case study: The installation of the mammoth in 1907 reflects once more the ambivalence of the Junta and its networks of Barcelonese naturalists and civil servants. The ‘antediluvian’ animal was intended to teach visitors to the Parc about the prehistory of Catalonia. Yet at the same time, the Junta felt the mammoth needed to be protected from likely damage and therefore erected a protective barrier around it (during the works, first wooden panels, then barbed wire, and after the inauguration a metal fence).67 The public was to be educated but also to be kept on a short leash. As the members of the Junta put it: the fence was necessary due to the ignorance and lack of culture of people who could not appreciate the importance of the work.68 The magazine La Esquella de la Torratxa satirized this patronizing attitude that ascribes to the public the nature of an animal: the fence around the reproduction of the mammoth was to ensure that ‘no one would hurt it’.69 And only a few months later, with the petrographic collection taking shape outside the museum in early 1908, the Junta saw itself faced with the very same problem. In order to protect the samples of different stones and the labels attached to them against ‘a certain type of public’, it proposed to put a fence around the collection as well.70

These examples from the zoo, the mammoth and the petrographic collection show the fear of, or at least the uneasiness toward, the ‘masses’. The ‘masses’ in this discourse were constructed as the constitutive opposite of the bourgeois individual, civilized and educated, receptive to what the Parc had to offer as a school of ‘civic nature’. The contradictions in the agenda of the Parc as a public space for science are obvious: Its content was designed to educate and maybe even more to pacify the ‘masses’ (read: the workers) yet at the same time the Junta was afraid and put up panels with prohibitions and fences in order to protect itself.

Our third case, the exhibition on pisciculture points in a different direction. In their rhetoric Barcelonese naturalists would frequently defend the frontier between the spectacular and the instructive. Yet the case of the ‘travelling whale’ shows that the border between popular culture – Paralelo – and bourgeois popular education – the Parc – was porous. The organizers of the exhibition did not miss out on the opportunity to attract new audiences by buying and displaying such a spectacular specimen. In fact, the various incentives on offer – seafood, concerts, activities for children – indicate a growing awareness that certain concessions were called for in order to satisfy the desire of the ‘real visitor’ for some good entertainment. The exhibition on pisciculture may even be interpreted as a learning process for the Junta.

In the summer of 2014, the Natural History Museum of Barcelona and the Barcelona Zoo were digging for their roots. They organized a public lecture series entitled ‘La Ciutadella, Barcelona’s first science park’ in an attempt to connect the past with the present.71 In 1907 Norbert Font chose a different key word, he envisioned a ‘veritable park of culture’. For Barcelona’s fin-de-siècle naturalists, the Parc was certainly more than just about science. The time between the approval of Fontserè’s plan in 1872 and the inauguration of the Museu de Ciències Naturals de Catalunya in 1917 was marked by several agendas with distinct ideological underpinnings. These programmes were characterized by their different notions of nature – and their common notion of the public.

Fontserè’s eclectic plan reflected both his (older) romantic understanding of nature as manifested in the grottos of the Cascade as well as a utilitarian one with its focus on applied natural history. It was this utilitarian understanding of investigating and using nature as a resource that is common to all the different ‘Parc agendas’. In its purest form we find it in the Junta técnica (1893–1906), and in the person of Francesc Darder, his zoo and his acclimatization efforts. As we have seen, in a radically different political context, the creation of the new Junta in 1906, focusing on the natural history of Catalonia (and thus national identity) marks a turning point.

Yet these two agendas were largely compatible. Many of the activities promoted by the Junta were based on a utilitarian concept of nature, in line with the programme of the preceding Junta técnica.72 The large-scale programme to enrich the Catalan fresh waters with ‘foreign’ species of fish between 1908 and 1915 clearly shows this. It has been argued that doing applied science may be considered a specific feature of Catalan science at the time.73 This is certainly the case with the Parc. Both the Junta técnica and the Junta were eager to demonstrate that nature as a resource could be controlled, improved and exploited in order to modernize Catalonia. What was needed was research in applied natural history.

Yet at the same time, the citizens needed to be won over to support this ‘civic nature’. The agenda that the two Juntas promoted aimed at more than simply increasing the knowledge of the visitor to the Parc about the natural world. The citizens were essential in order to fully realize the utilitarian programme. They were needed as contributors to the collections of the Parc, most notably to the Museu Martorell and the Petrographic Collection. They were supposed to buy animals and animal products at the zoo, in order to breed and raise animals themselves, be it on a domestic or even on a commercial scale. They were encouraged to come up with their own business ideas inspired by the Museo Zootécnico or by one of the exhibitions. Some of the bigger fish caught by ‘ordinary people’ in the spring of 1913 in the lake of Banyoles went straight to the exhibition on pisciculture in Barcelona. They were presented as direct proof of the success of the Festa de Peix and the introduction of the exotic species into Catalan fresh waters.74

These attempts to recruit the ordinary citizen, thus ascribing at least in principle an active role to him, stand in stark contrast to the patronizing attitude of both the Junta técnica and the Junta. The way the facilities of the Parc offered knowledge was ‘top down’. The experts in applied natural history told the presumably ignorant citizen what to do (and, for example, in the case of the mammoth also what to believe). The Juntas found themselves in a seemingly contradictory position. On the one hand, they depended on the general public for their agenda to have a noticeable impact. Yet on the other hand they were suspicious about the lack of education and proper behaviour of the ‘masses’. They felt they needed to protect the animals of the zoo and the mammoth in the Parc from evildoers. This boils down to the opposition of an imagined citizen versus a real visitor.75 The former is eager to participate in the projects of applied natural history proposed by the Juntas in the Parc. The latter tends to seek amusement rather than instruction. It seems that particularly with the exhibitions in the Parc from 1909 onward, the Junta tried to combine instruction with entertainment. The acquisition of the large stuffed whale by the organizers of the exhibition on pisciculture in March 1913 is the most striking example of this attempt. And the Festa del Peix hosted in smaller Catalan towns became a highly popular event, at least judging by the extensive press coverage. Yet there was always competition for public attention even within the Parc. This competition became particularly fierce in 1911 when the amusement park Saturno opened in the heart of the Parc, drawing the masses within earshot of the Museo Martorell and the zoo.76

The Saturno only provided technological fun for 15 years in the Parc, yet the stone mammoth is still there. More than 100 years after its inauguration, the huge sculpture nowadays provides a much-used photo opportunity. On Sundays one may even have to queue in order to position oneself behind the enormous trunk – a trunk that is vertically bent so that it easily serves as a seat for a child. The fence around it is long gone. It seems like an ironic twist of history that this creature, this strange mix of old and new, of defending biblical chronology and advocating modern political Catalanism, of conservative ideology and state-of-the-art technology, is nowadays an eye-catcher for tourists from all over the world, and is thus probably more entertaining than instructive.

1We would like to thank Helen Cowie and Christina Wessely for their most helpful reviews. Ferran Aragon and José Pardo are our indispensable ‘Parc partners’. Many authors of this volume contributed in different ways to this chapter. Research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, grant HAR2013–48065-C2–1-P.

2For reasons of brevity and easy identification, we will henceforth refer to the Parc de la Ciutadella as ‘Parc’. It was originally mostly referred to as ‘parque de Barcelona’. The specification ‘de la Ciutadella’ came into use much later. Due to historical circumstances and concrete context, the official name also changed between ‘parque’ (Spanish) and ‘parc’ (Catalan).

3The most important study in this respect is Lynn K. Nyhart, Modern Nature: The Rise of the Biological Perspective in Germany (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 2009). Also see her earlier article ‘Civic and economic zoology in nineteenth-century Germany: The “living communities” of Karl Möbius’, Isis 89 (4) (1998): 605–30 and Denise Phillips, Acolytes of Nature: Defining Natural Science in Germany, 1770–1850 (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012).

4For a first exploration of this topic, see Laura Valls, ‘El museo de ciencias naturales de Barcelona (1882–1917): popularización de las ciencias naturales dentro y fuera del museo’, Geo Crítica. Cuadernos Críticos de Geografía Humana 15 (918) (2011).

5There is a vast literature on the public park in the nineteenth century. To quote but a few relevant books: Hazel Conway, People’s Parks: The Design and Development of Victorian Parks in Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991); Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press, 1992); Heath Massey Schenker, Melodramatic Landscapes: Urban Parks in the Nineteenth Century (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2009).

6Diego Armus, La ciudad impura. Salud, tuberculosis y cultura en Buenos Aires, 1870–1950 (Buenos Aires: Edhasa, 2007), Chapter 1.

7Conway, People’s Parks, p. 29.

8Dorceta E. Taylor, ‘Central Park as a model for social control: Urban parks, social class and leisure behavior in nineteenth-century America’, Journal of Leisure Research, 31 (4) (1999): 420–77.

9Conway, People’s Parks, pp. 206, 222.

10For the early history of the Parc, see: Adolfo Florensa, ‘José Fontserè y el Parque de la Ciudadela’, in Miscel·lània Fontserè Barcelona (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1961), 175–82; Miquel Vidal, ‘El Parque de la Ciudadela, entre el Romanticismo y la “Renaixença”’, Arquitecturas Bis. Información gráfica de actualidad, 40 (1981), 14–17; Ramon Grau and Marina López, ‘La gènesi del Parc de la Ciutadella: projectes, concurs municipal i obra de Josep Fontserè i Mestre (1868–1885)’, in El pla de Barcelona i la seva història. Actes del I congrés d’història del Pla de Barcelona (Barcelona: La Magrana, 1984), 441–67; Manuel Arranz, Ramon Grau and Marina López, El Parc de la Ciutadella. Una visió històrica (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona-L’Avenç, 1989); Stephanie Kickum, ‘Auf dem Weg zu internationaler Bedeutung: Parkanlagen in Spanien’, in Angela Schwarz (ed.), Der Park in der Metropole. Urbanes Wachstum und städtische Parks im 19. Jahrhundert (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2005), 161–218, pp. 193–209.

11José Fontserè, Proyecto de un parque y jardines en los terrenos de la ex-ciudadela de Barcelona (Barcelona: Narciso Ramírez y Compañía, 1872), p. 5; Terence Young, ‘Modern Urban Parks’, Geographical Review – Thematic Issue: American Urban Geography, 85 (4) (1995): 535–51, p. 538.

12Fontserè, Proyecto, pp. 12–16.

13See Chapter 3 of this volume.

14There is an enormous amount of literature on this exhibition: For a history of science point of view, see Agustí Nieto-Galan, ‘Scientific “marvels” in the public sphere: Barcelona and its 1888 International Exhibition’, HoST – Journal of History of Science and Technology, 6 (2012): 33–63.

15For the general context, see Antoni Roca-Rosell and Vicent L. Salavert, ‘Nacionalisme i ciència als Països Catalans durant la Restauració’, Afers: fulls de recerca i pensament, 18 (46) (2003): 549–63.

16Ferran Aragon, Anàlisi prosopogràfica del Catòlic-Catalanisme Científic (1904–1910) (Master Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 2012).

17Norbert Font, ‘Junta autònoma de Ciències Naturals’, La Veu de Catalunya, 18 September 1907 (evening edition), 1–2, and ‘Junta autònoma de Ciències Naturals II’, La Veu de Catalunya, 2 October 1907 (morning edition), 1. Quote from the second article.

18Fontserè, Proyecto, p. 15.

19Francesc Darder, ‘Variedades’, El Naturalista, 3 (1886), 19. Reprinted in La Vanguardia, 4 March 1886, 4–5. Darder was a veterinarian, taxidermist, and author of natural history journals and books. A thorough investigation of his manifold activities is a desideratum.

20On the acclimatization movement of the nineteenth century, see: Michael A. Osborne, Nature, the Exotic, and the Science of French Colonialism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994).

21Warwick Anderson, ‘Climates of opinion: Acclimatization in nineteenth-century France and England’, Victorian Studies, 35 (2) (1992): 135–57; Osborne, Nature, p. 127.

22Santiago Aragón, El Zoológico del Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Madrid. Mariano de la Paz Graells (1809–1898), la sociedad de aclimatación y los animales útiles (Madrid: Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, CSIC, 2005), pp. 142–88 and particularly pp. 199–200.

23The literature on the early history of the Barcelona zoo is sparse but see: Emili Pons, El parc zoològic de Barcelona. Cent anys d’historia (Barcelona: Edicions 62, 1992), pp. 48–53; Ramon Alberdi and Rafael Casasnovas. Els Jardins de Martí-Codolar. La Granja Vella (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, Districte d’Horta-Guinardó, 1999), pp. 46–53; Rossend Casanova, ‘Francesc d’Assís Darder i l’origen del Parc Zoològic de Barcelona’, Revista de Catalunya Barcelona, 142 (1999): 36–41; Daniel Venteo, ‘La Ciutadella i el Zoo, una història ciutadana paral·lela’, in Parc del zoo, el cor de la Ciutadella (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2009), 15–61.

24Pons, El parc zoològic, p. 50.

25Darder complained regularly to his superiors that he had barely enough money to feed the animals; for example, AMCNB (Arxiu històric, Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona), 3/6, 18 March 1902; also Pons, El parc zoològic, p. 64. The first guide to the zoo also mentioned the prices for the animals on display, see Catálogo del Parque zoológico municipal (Barcelona: Henrich, 1897).

26Gustave Loisel, Histoire des ménageries de l’Antiquité à nos jours (Paris: Doin, 1912), vol. 3, pp. 269, 290–1; Roland Baetens, The Chant of Paradise. The Antwerp Zoo: 150 Years of History (Tielt: lannoo, 1993), pp. 94–5; Osborne, Nature, p. 122; for Vienna, see Gerhard Heindl, Start in die Moderne. Die Entwicklung der kaiserlichen Menagerie unter Alois Kraus (Wien: Braumüller, 2006), p. 39.

27Casanova, ‘Francesc d’Assís Darder’, pp. 37, 39.

28Loisel, Histoire des ménageries, p. 110.

29Ramón Turró, ‘En Francesc Darder’, La Veu de Catalunya, 16 April 1918 (morning edition), 9.

30Ayuntamiento Constitucional de Barcelona, Informe relativo a la organización y sucesivo desenvolvimiento de los Museos y Parque histórico-naturales de Barcelona (Barcelona: Junta Técnica de los Museos de Ciencias Naturales, Parque Zoológico y Jardín Botánico, 1899), p. 25.

31Anuario Estadístico de la Ciudad de Barcelona (Barcelona: Henrich, 1902), pp. 309–10; Rossend Casanova, ‘El museo zootécnico de Barcelona. Uso y abuso del patrimonio efímero tras la Exposición Universal de 1888’, in Arte e identidades culturales (Oviedo: Universidad de Oviedo, 1998), 425–32, p. 428; Nieto-Galan, ‘Scientific “marvels”’, p. 61.

32Josep Maria Camarasa, Cent anys de passió per la natura. Una història de la Institució Catalana d’Història Natural: 1899–1999 (Barcelona: Institució Catalana d’Història Natural, 2000), p. 40.

33AMCNB 15/1, 15 September 1906; James A. Secord, ‘Monsters at Crystal Palace’, in Soraya de Chadarevian and Nick Hopwood (eds), Models. The Third Dimension of Science (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004), 138–69.

34Secord, ‘Monsters’, p. 161.

35Herman Reichenbach, ‘Carl Hagenbeck’s Tierpark and Modern Zoological Gardens’, Journal of the Society for the Bibliography of Natural History, 9 (4) (1980): 573–85, p. 579.

36‘Nueva industria’, Resumen de arquitectura, 1 January 1895, 7.

37Font, ‘Junta autònoma II’; Jordi Bohigas, ‘Per Déu i per la ciència’. L’Església i la ciència a la Catalunya de la Restauració (1874–1923) (PhD thesis, Universitat de Girona, 2011), p. 278.

38On the history of the mammoth, see Julio Gómez-Alba, ‘El mamut y la colección petrológica de grandes bloques del Parque de la Ciudadela (Barcelona, España)’, Treballs del Museu de Geologia de Barcelona, 10 (2001): 5–76, pp. 7–11; and Laura Valls, ‘El mamut de la Ciutadella (1907). Biografia d’un objecte urbà’, Afers: fulls de recerca i pensament, 30 (80/81) (2015): 243-68.

39Gómez-Alba, ‘El mamut’, provides an exhaustive account of the provenance of the stones. Most but not all of the samples were from sites in Catalonia.

40AMCNB, 25/14, 1910.

41Rossend Casanova, El Castell dels Tres Dragons (Barcelona: Museu de Ciències Naturals/Institut del Paisatge Urbà i la Qualitat de Vida, 2009), p. 67.

42Valls, ‘El museo de ciencias naturales’, p. 15.

43See, for example, James Ramsey Gibson Maitland, On the culture of Salmonidae and the Acclimatization of Fish (London: W. Clowes and Sons, 1883).

44AMCNB, 22/18, September 1908.

45The topic has not yet been studied in any depth. For a useful first step in collecting material, see Georgina Gratacós, ‘La festa del peix a Banyoles el 1910, una recerca documental i fotogràfica’, Jornadas imatge i recerca, 12 (2012).

46Joan Vidal, L’Estany de Banyoles (Girona: La Económica, 1925), p. 63.

47‘Exposició de piscicultura, acte inaugural’’, La Veu de Catalunya, 21 December 1912 (morning edition), 2.

48Ibid.

49‘Balena de 13 metres’, La Veu de Catalunya, 17 December 1912 (morning edition), 4.

50‘Última hora’, L’Esquella de la Torratxa, 27 December 1912, 844.

51‘Exposició regional de piscicultura i pesca’, La Veu de Catalunya, 19 March 1913 (evening edition), 7.

52Casanova, El Castell dels Tres Dragons, p. 69.

53‘Exposició regional de piscicultura i pesca’.

54AMCNB 94/002, 27 April 1909, p. 207.

55Darder, ‘Variedades’.

56The case of popular astronomy – ‘a useful tool to discipline and preach morality to citizens’ – is analogous; see Chapter 9 in this volume.

57Darder, ‘Variedades’.

58Conway, People’s Park, pp. 60–1.

59On the zoo disciplining its visitors (what they should and should not do), see Christina Wessely, ‘Künstliche Tiere etc.’. Zoologische Gärten und urbane Moderne in Wien und Berlin (Berlin: Kadmos, 2008), pp. 66–73; Oliver Hochadel, ‘Im Angesicht des Affen. Die Besucher des Tiergartens im 19. Jahrhundert’, in Sabine Nessel and Heide Schlüpmann (eds), Zoo und Kino (Frankfurt/M: Stroemfeld, 2012), 29–48, pp. 30–2.

60The incident with the cigarette is related in Diario de Barcelona, 29 September 1892 (morning edition), 11316; ‘Justicia elefantisiaca’, El Diluvio, 29 September 1892 (morning edition), 8221; La Vanguardia, 3 October 1892, 1. Also see Pons, El parc zoològic, pp. 51–2.

61El Diario de Barcelona, 14 October 1892, 11974; Pons, El parc zoològic, p. 52.

62Oliver Hochadel, ‘Vor den Gitterstäben: Die Besucher der Menagerie Schönbrunn im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert’, in Mitchell G. Ash and Lothar Dittrich (eds), Menagerie des Kaisers – Zoo der Wiener. 250 Jahre Tiergarten Schönbrunn (Wien: Pichler, 2002), 158–79, pp. 173, 176.

63La Vanguardia, 4 October 1892, 2; Pons, El parc zoològic, p. 52.

64For an instructive comparison on how La Vanguardia and El Diluvio represent science, see Matiana González-Silva and Néstor Herran, ‘Ideology, elitism and social commitment: Alternative images of science in two fin de siècle Barcelona newspapers’, Centaurus 51 (2) (2009): 97–115.

65‘La coleccion zoológica del Parque’, El Diluvio, 22 September 1892 (morning edition), 3 (8012); also see El Diluvio, 25 September 1892 (morning edition), 8111. On the role and place of El Diluvio in the public sphere of Barcelona, Stephen Jacobson, ‘Interpreting Municipal Celebrations of Nation and Empire: The Barcelona Universal Exhibition of 1888’, in William Whyte and Oliver Zimmer (eds), Nationalism and the Reshaping of Urban Communities in Europe, 1848–1914 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 74–109, pp. 98–9.

66‘Que se aclare’, El Diluvio, 13 October 1892 (morning edition), 8692–3.

67Gómez-Alba, ‘El mamut’, p. 8.

68AMCNB, 15/001, 31 August 1907, pp. 20–1.

69La Esquella de la Torratxa, 13 September 1907, 603.

70AMCNB, 94/002, 24 February 1908, p. 117.

71See http://barcelonacultura.bcn.cat/descobreix/la-ciutadella,-el-primer-parc-cientific-de-barcelona#.VK0WNSfz9PR (last accessed 7 January 2015).

72See the programmatic article by Font, ‘Junta autònoma II’, where the Catalanist and the utilitarian agenda are neatly fused.

73Roca-Rosell/Salavert, ‘Nacionalisme’, pp. 552, 555.

74See the substantial documentation in Francesc Darder and Jerónimo Darder, Piscicultura: Crónica piscatoria (Barcelona: Hijos de Domingo Casanovas, 1913).

75This split between an ideal and real visitor was typical at the time. For example, the Viennese naturalist and short-term zoo director Friedrich Knauer (1850–1926) was struggling along the same lines; see Hochadel, ‘Im Angesicht’, pp. 30–1.

76See Chapter 5 of this volume.