Recent memories of the 1888 Universal Exhibition could not conceal the poor living conditions and social strife that plagued the city’s working class in November 1889.2 That month Barcelona hosted the Segundo Certamen Socialista (The Second Socialist Contest), a competition organized by various anarchist groups and labour societies. At the Palacio de Bellas Artes (Palace of Fine Arts), one of the emblematic buildings erected for the exhibition, and before an audience of over 20,000, contestants read a long series of prize-winning speeches. Some delivered high praise for scientists (for example, Lamarck, Spencer, Darwin, Tyndall and the like) or for science in general. The undisguised aim was to revitalize anarchism while simultaneously demonstrating the working class’s competence on literary, sociological and scientific issues.3

Forty years later, in 1929, Barcelona was not only a great modern industrial power, it had also become one of the most important centres of anarchist activity – an exception in a world which, in general, had turned its back on the movement. These changes took place while Barcelona was transformed into something very different from the ideal of the functional and socially coherent new city envisioned by urban planners. Far from any sort of rational planning, its spectacular urban and demographic expansion was chaotically moulded by market forces that imposed a deep socio-spatial segregation.4 A veritable abyss had opened up between the proletarian neighbourhoods and upper-middle-class districts. The divide was reflected in lifestyles and dress codes, but even more so in the human body itself. Hygienists and workers alike were driven by the consequences of pauperism, disease and physical deformities to remark upon the ‘differentiating characteristics [...] of the proletarian race’.5

This chapter attempts to explain how this process affected anarchist efforts to manage scientific knowledge by using a panoramic view. A brief sketch of the political and spatial geography of libertarian scientific communication in the city is provided to highlight how social polarization reinforced another ongoing process: the widening gulf between the anarchist cultural universe and that of middle-class radicals. As interclass bridges became increasingly untenable, not only intellectuals but even scientists and technicians began to arouse suspicion amongst the anarchist ranks. After 1910 the cultural fabric of anarchist–syndicalism grew into a network oriented towards the autonomous management of scientific knowledge.6 It is not easy to bring the experience of those efforts to modern readers. The relationship between anarchism and science, on a global scale, has been largely overlooked by historians of science, Piotr Kropotkin’s evolutionary thought being the sole exception.7 In the case of Spain and Barcelona, the situation is only slightly better. Stimulated by previous contributions made by historians of political and cultural thought,8 there has been growing interest recently in the relationship between Darwinism and the libertarian movement,9 the connections between New-Malthusianism, anarchist groups, contraception and eugenics,10 and some important, though incipient, contributions on medicine and anarchism.11 However, it can be said that we are just now beginning to scratch the surface. Small wonder no serious attempt has been made to link history of science, anarchism and urban development in Barcelona.

This is an oversight that appears paradoxical in light of the exceptional importance given by the movement to scientific culture. Anarchists drew from established Enlightenment, radical and socialist traditions in which confidence in the transformational possibilities of rationality and science was a defining characteristic. The promise of social harmony resided in revolution, but also in science. A supreme guarantor of material progress, it seemed to provide support to a materialist world view that left little room for one of anarchists’ bête noirs: organized religion. But the utility of scientific knowledge was not limited to its hypothetical potential in eroding the Catholic Church’s authority. One of the fundamental objectives of the libertarian movement was the education of the working class. Social revolution would remain incomplete without a revolution of minds.12 This would be achieved not only by introducing new ideas, but by completely overcoming atavistic traditions, customs and habits. As in the case of republicans and socialists, the aim was to disseminate rationality in daily life.13 Science was to spearhead this process of emancipation. In short, the management of scientific knowledge was a central aspect of an alternative political subculture which saw itself as completely rational, and in this way different from both bourgeois culture and, not without tensions, prevalent patterns of popular culture.

It is difficult to ascertain the causes of this paltry historiographical presence. In the present case, however, there is a legitimate suspicion that the popular image of anarchism, which is still associated with nineteenth-century terrorism, raises doubts about whether science and anarchism actually have anything to do with one another. Nonetheless, and despite the fact that some libertarians supported terrorism, the vast majority of them had little or nothing to do with the logistical aspects of such attacks and many openly criticized such a form of political violence.14 On the other hand, some historians have portrayed anarchism as a form of modern millenarianism in which eschatological elements played a prominent role. They also linked its alleged primitive features with industrial underdevelopment. However, this is hardly consistent with the popularity of the libertarian movement in a big industrial city as Barcelona. Moreover, other historians have highlighted the social and historical rationality of the Spanish anarchist movement’s actions.15 That said, the relative weakening of the Catholic Church’s influence among workers did not eliminate certain emotional needs although the daily praxis of the libertarian militants might be described as rational. The redemptive role assigned to science is far from incompatible with utopian expectations.

Anarchism is a historiographical object that resists definition. It was a polymorphous movement with a wide range of tendencies.16 However, it is noteworthy that the vast majority of Barcelona’s libertarians shared communal, if not collectivist, ideals, which took the principle of solidarity as a fundamental axiom. They were quite far from the extreme-right movements that define themselves as libertarians in the USA nowadays.17 Nonetheless, the social philosophy of the libertarian movement does not fit well within any of historiography’s traditional classifications. Born from the cleft between supporters of Karl Marx and those of Mikhail Bakunin at the First International, anarchism is usually identified as an unorthodox branch of socialism. However, origins notwithstanding, historical research made it clear that Spanish anarchism and liberalism do share a number of significant similarities. In the words of J. Álvarez Junco, anarchist ideology fell within the intellectual framework of liberal rationalism, faith in progress, the goodness of mankind, and harmony between nature and society.18 This is consistent with one of the libertarian’s most cherished beliefs: science was supposed to reveal the justice and harmony in nature, one of the great enlightenment myths that anarchists readily adopted.19

Historians often claim that the libertarian movement in Catalonia must be understood within the coordinates of the profound unity of the left’s political culture, dominated by the values and principles of republicanism, which survived right up to the Spanish Civil War.20 But care should be taken not to interpret the political subcultures of anarchism, socialism, and republicanism as one indistinguishable force. The libertarian notion of revolution, for example, included the immediate objectives of socializing the means of production and complete abolition of the state. That was far from the wildest dreams of the most radical branches of republicanism and affected decisively libertarian views on science. While science itself was rarely questioned, scientists were not so warmly embraced. Reticence towards them was based both on their alleged bourgeois standing and anarchists’ vision of modern history. Libertarians acknowledged that the liberal bourgeoisie had been a progressive factor in the emancipation of mankind. It was not the case in the last decades of the nineteenth century: the upper-middle class had already fulfilled its historical mission. The bourgeoisie only devoted its efforts to defend class privileges.21 It was the people that now had to shoulder the redemptive mantle. The virgin intelligence of those with no privileges to defend, that is, the workers, made it possible for them to completely accept the self-liberating implications of scientific knowledge. That could not be expected of the bourgeoisie anymore, scientists included. On their view, social status does not so much affect the making knowledge process as it does the moral capacity of different social classes to accept the implications revealed by new scientific truths.22 Thus, the opposition between bourgeoisie science and working class science was often depicted as the confrontation between a science consciously limited by class interests – and thereby compromised, incomplete and truncated – and one guided by a proletariat whose only real interest is truth.23

On top of this, science was also conceived as collective capital, a sort of knowledge bank accumulated by mankind from generation to generation. On that understanding, anarchists saw this universal heritage as having been kidnapped by one class and, in a sense, enclosed within institutions dominated by the sphere of privilege, such as universities and academies. From the libertarian perspective, it was more important to disseminate knowledge that had already been discovered than promote new discoveries. The aim was for science to become ‘the life of all’, and to cease to be an unattainable luxury for workers. That is why science occupied such an important role in anarchists’ editorial activities. However, at first glance, what was edited and distributed shows that the literary universe of Barcelona’s anarchist elites was not all that different from that of the middle class, which paid significant attention to the works of Spencer, Haeckel, Darwin and Lombroso. Were the anarchists, as some historians claim,24 mimicking the dominant models of high culture? No, they were using high culture. It may be obvious that Ernst Haeckel, Herbert Spencer, Ludwig Büchner, Enrico Ferri, Théodule Ribot and Lombroso were read and disseminated, but all readings modify their object and the established order of the original text.25 The manifest resignification of terms like ‘survival of the fittest’, ‘normality’, ‘degeneration’, ‘disease’, ‘environment’, indicates a use of scientific knowledge far beyond the fiction of a mere pyramidal diffusion of knowledge.26 As Anselmo Lorenzo said, ‘from bourgeois science we will take the truth, and we will do away with the sophisms that serve as the basis of privilege [...]’.27

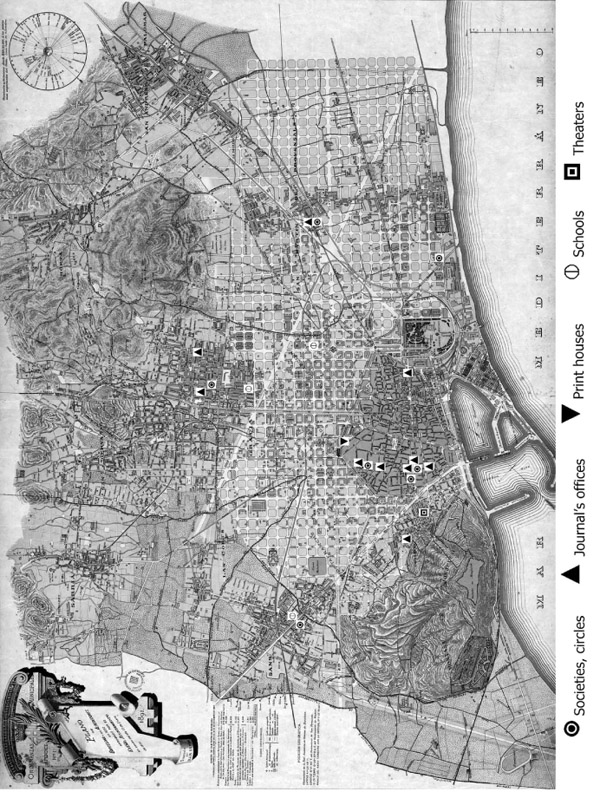

Theoretical digressions aside, it is important to understand the geography of scientific communication within the city. It is by no means easy to draw a map of anarchist cultural institutions in Barcelona, which, to a greater or lesser extent, were involved in the debate of scientific ideas. In the case of late nineteenth-century Paris, we know that the areas in which activists were recruited – the mostly proletarian north-eastern part of the city – do not coincide with the areas of greatest anarchist activity (Montmartre).28 Could the same be said of Barcelona, or are these two unique cases? What we know for sure is that in the 1880s and 1890s most libertarian activity was concentrated in city’s old sector, particularly the run-down areas today known as Raval. This was a traditional stronghold of artisans and workers. At the same time, the role of artisans and labourers from nearby villages (for example, Sant Martí de Provençals, Sants, and Gràcia) that had just been incorporated into Barcelona in 1897 should not be neglected.

Yet anarchists also inherited a federalist tradition which inclined them to decentralization. Anarchist cultural life could have been geographically complex and not limited to workers’ official organizations: cafés played also an important role. Libertarian cafés explicitly distanced themselves from popular taverns: they provided board games, but also books, newspapers and pamphlets. They organized collective readings and even presented theatrical works. The mobility and decentralization of this extensive network further increased in 1888 when the syndicalist organization, Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española (FTRE), was officially dismantled. It dissolved into affinity groups of between five and ten members – ‘grupos de afinidad’ – which became the nuclear elements of libertarian action until the emergence of anarchist–syndicalism in the 1910s.29 Instability was also inherent in the anarchist movement. Frequent cycles of repression meant the constant appearance and disappearance of groups, networks and their respective media mouthpieces. Even more decisive was the international character of the libertarian movement. Indeed, there was such a broadly-flung network of communication that applying the concept of local context requires extreme caution.

Anarchist readings of Darwinism, for instance, had little or nothing to do with the debates that were being generated on the topic in Barcelona and throughout Spain.30 Instead they owed more to the thought of the Russian anarchist Piotr Kropotkin, a theorist who greatly influenced the libertarian movement on a global scale. Such interpretations were also coloured by the recognition, evident after the mid-1880s, that some venerated figures in the Darwinist field, Ernst Haeckel31 and Herbert Spencer,32 were attempting to discredit socialism. In this respect, the central problem for libertarians was the dominant interpretation of the Darwinian metaphor of struggle for life. Presenting nature as a battlefield challenged the libertarian belief in nature as a harmonious order.33 In the face of this challenge, anarchists from Barcelona attempted to remove the Malthusian sting from Darwinism by denying the existence of an imbalance between population and (food) resources. Above all, particularly during the 1880s, they supported what Antonello Lavergata identifies as one of the most common forms of softening the edge of literal interpretations of the struggle for life. Libertarians began to support the claim that, while the most ferocious forms of struggle could have played a significant role during the early stages of evolution, as humanity progresses, the struggle is moderated,34 or even transferred to less bloody arenas, such as that of the intellect. Although wars of mutual destruction occurred along the way, solidarity was seen as the final stage of this process.35 This was hardly original. The Parisian publication Le Révolté, of enormous influence in the libertarian movement on a global scale, followed the same path.36

Presenting things this way had its advantages: modern society’s ferocious struggle for life was seen as the pathological preservation of behaviours typical of primitive evolutionary stages. Actually, this argument became a rhetorical device frequently used to condemn capitalism. It also, however, had equally obvious disadvantages: interpreting the universe of the living as a great calamity is contradictory to visions of a harmonious nature. In 1890–1896, Piotr Kropotkin provided the way out in his celebrated series of articles on mutual aid and Darwinism published in The Nineteenth Century, one of the most prestigious English monthly reviews. He inverted the terms: solidarity is the predominant factor in nature, not a Malthusian struggle between individuals for space and resources. Mutual aid, on the contrary, is the main factor explaining progressive evolution. Social life and ethical norms are not the result of an extended evolutionary process that takes us increasingly apart from our natural past. On the contrary, morality is based on social instincts that we inherited from our animal ancestors.37 After 1892, parts of Kropotkin’s articles were translated and published in the influential Barcelona weekly, El Productor. Kropotkins’ views on Darwinism were widely used for internal debates, specifically, during the first years of the twentieth century, when the conflict between those anarchists who supported kropotkinian communal ideals (the majority) and radical individualists inspired by Stirner and Nietzsche arose.38 It is clear that Barcelona’s libertarian elite managed scientific knowledge – Darwinism – to make it fit with their deep beliefs and the peculiarities of local agendas. But this management should not be understood without a selective appropriation of what had been said initially on that topic by the French libertarian press and Kropotkin’s reading of Darwinism.

Now, it is the press that occupies the leading role in interaction between the local and the global. It is through the press that Barcelona became a node in a network of libertarian communication. How was it read? In a city where not all workers were literate, collective reading certainly had a role, the exact relevance of which remains to be determined.39 It is not a minor point: the reading aloud of flyers had already been instrumental in the creation of a public sphere in France since the eighteenth century.40 In the case of Barcelona’s anarchists its utility was clear: as in Buenos Aires it could help the workers get to know great works of thought and it would facilitate the recruitment of new supporters.41 Obviously the nature of available sources makes it difficult to find concrete examples linked with science. However, there exists written evidence of one particularly significant collective reading a few years before the Universal Exhibition of 1888. In April 1885, at the headquarters of the Barcelona Society of Printing Press Workers, and before an audience comprising ‘the members and their families’, a direct translation of some articles published in La revue socialiste under the title ‘Transformisme et socialisme’ was read out loud.42 Significantly, the goal of his author, the French socialist and free thinker Louis Dramard, was to challenge Ernst Haeckel’s attempts to disassociate Darwinism and socialism.

The foregoing considerations do not exhaust the question: the political geography of the city is equally decisive. From a politico-cultural perspective, one can describe the history of libertarian cultural institutions as a process of generating their own independent spaces. Their progress reflected, in a sense, the growing isolation of the working class in the city. That was a long process, not exempt from setbacks. Already during the Sexenio Democrático (Democratic Six Years) (1868–1874), the internationalists of the Spanish Regional Federation (FRE) of the International Association of Workers (AIT) tried to drive a wedge between the workers and the middle class, aiming to establish thereby their hegemony within labour organizations. Towards the 1880s and 1890s things began to change. Anarchists created their own institutions – casinos, cafés, publications, secular schools and so on – that tended in principle to reinforce class divisions.43 They were relatively complex organizations that sponsored cultural activities, like soirees or conferences, and even began to edit periodicals. In the 1880s the social circle of workers known as ‘La Regeneración’ (located at 2 Sant Olegari Street) stood out for its influence in the city as the driving force behind two of the most important publications in the history Spanish anarchism: El Productor and Acracia. In the latter, the relationship between socialism and Darwinism was discussed at depth.

However, Barcelona was not yet a completely divided city. There were cultural spaces for interclass collaboration between libertarians and radicalized middle-class groups, especially the republican federals by the late 1880s. Anticlericalism, a constant feature of the Leftist movements of southern Europe throughout the nineteenth century and up to the Second Vatican Council, cemented the collaboration between republicans, anarchists and freemasons. The context was favourable to it as well. There was a feeling that it was possible to actively compete with the power of the church. Moreover, anticlericalism was known to be a powerful mechanism of popular mobilization.44 Such informal alliances were solidified, at the same time, through the freethinking movement, one of the most important political and cultural currents in Western Europe.45 The movement developed extensively in Barcelona from the last decades of the nineteenth century. Though it was presented as an interclass movement of heterogeneous social composition, the free thinkers of Barcelona came to defend political principles that belonged to the political culture of the working-class movement.46 Freethinkers undertook the secularization of civil life through the dissemination of scientific rationalism, the popularization of non-Catholic social rites (for example, civil weddings and funerals) and, above all, the creation of secular schools. From this perspective, science occupied an essential place in the symbolic realm. Already in 1869, the preamble to the provisional regulations of the Free-thinking Society of Barcelona, led by the anarchist doctor Gaspar Sentiñón, stated: ‘[...] the good cannot exist outside of the truth, and [...] there is no other truth than that provided by science’. 47

Actually, freethinkers devoted a good part of their time to scientific communication. The press organ of the Free-thinking Society of Barcelona, La Humanidad, was instrumental in the propagation of a markedly materialist reading of Darwinism, in which the influence of Ernst Haeckel was noteworthy. From 1885, and until the beginning of the 1890s, it was replaced by an association of free thinkers known as ‘La Luz’. This nucleus of activity combined republican leaders like Cristobal Litrán, a large faction of notable anarchists (with the exception of the anarchist–communists), and a few high-ranking members of the Freemasonry, like its organizer Rossend Arús.48 Defined by its radical atheism, ‘La Luz’ collided with the spiritists. That might have caused a bit of internal debate: some spiritists were politically radicalized and collaborated actively in free-thinking activities.49 The anarchist and engineer Fernando Tarrida del Mármol defended the uncompromising materialist position of ‘La Luz’, basing it on scientific authority. He made liberal use of his particular reading of the political and religious implications of thermodynamics, then a matter of debate both within and outside of Spain.50 On top of this, he provided a sketch of Darwin’s theory, which helped him to conclude that there was a logical explanation of the universe and man that dispensed ‘entirely the hypothesis of the divine spirit’.51 On the other hand, there were other spaces in which collaboration was part of daily life. That was the case of a celebre printing house ‘La Academia’, publisher of an important number of scientific books. Founded in 1877, it was owned by the republican federal Evarist Ullastres, giving jobs to some 60 workers. A number of them were anarchists who frequented the meetings of ‘La Luz’. Its disappearance, in the 1890s, represented a severe setback for the libertarian movement as a whole.

Things got worse when the cycle of terrorism/repression gained momentum in the last years of the nineteenth century. The bridges between moderate anarchists and republicans collapsed. The indiscriminate repression put an end to the freethinking movement itself. On top of it, reductionist conflation of anarchism with terrorism aggravated the situation. This conflation took as its scientific basis the extremely popular criminal anthropology of Cesare Lombroso. The anarchists – many of whom were ‘insane’, according to the new criminal taxonomy – were turned into the example of choice for the positivist criminology avowedly indebted to Darwin and Spencer. But the Barcelona libertarians were extremely critically aware in their own right. They did not limit themselves to discrediting the abusive identification of ‘anarchist’ with ‘degenerate’ but went further to attack the very foundations of Lombrosian thought, especially his theories about the biological nature of crime, synthesized in the emblematic figure of the natural-born criminal. 52

In the early years of the twentieth century, the old alliance between of free thinkers, radical republicans and some leading anarchists somewhat revived. In 1901 Francesc Ferrer Guardia founded La Escuela Moderna (The Modern School) a universal symbol of the fight between free thought and inquisitorial Catholicism.53 Ferrer’s goal was to create a both a model of rationalist education and an emancipatory tool for workers. It was based on strong scientism and uncritical faith on positivism. The influence of Ernst Haeckel’s materialist evolutionism permeated the entire intellectual fabric of The Modern School. In its daily activity, the collaboration of libertarians with figures of scientific respectability – such as the naturalist, republican and free thinker Odón de Buen54 – was not infrequent at all. The history of this pedagogical experiment ended in the worst possible manner. In 1909, Barcelona experienced one of the most important popular uprisings of its entire history: the Setmana Tràgica (the Tragic Week). Ferrer was falsely accused of promoting the riots and was executed by a firing squad. The question at hand is whether, at its base, this type of interclass collaboration amongst the liberal elements, typical of the nineteenth century, had already become an anachronism in Barcelona by the onset of the new century. Already in the 1890s the wave of terrorism made widespread the dystopian bourgeois nightmare of an uncontrollable, violent city. The strike of 1902, and the Tragic Week, augmented an existing upper-middle class’s distrust and many fled to the outskirts of the city.55 Collaboration became both spatially and symbolically difficult.

In 1910 a new actor entered the scene causing important changes: the anarcho-syndicalist Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (National Confederation of Labour) or CNT. Within a few decades it became the most important trade union in Spain. The CNT was born in a city characterized by an accelerating – and disorganized – expansion. Thousands of new immigrants coming from southeast Spain settled in a secondary periphery deeply segregated – both socially and politically – from the rest of the city. Libertarian cultural life, adapted to this socio-spatial changes. From the end of World War I until the 1930s, libertarian cultural associations known then as ateneos racionalistas (rationalist athenaeums), began to be active in the working-class suburbs where the anarchists had traditionally found the most support: such was the more or less intermittent operation of the rationalist athenaeums of Sants (1917–1923), Gràcia (1918), and Poble Nou (1918). By the 1930s these sorts of initiatives were extended to the new secondary peripheries and adjacent municipalities in accordance with the changes in the political layout of the city. The old working-class suburbs – and the densely populated centre (El Raval) – had ceased to be areas of undisputed anarchist hegemony. The secondary peripheries had been converted into the new breadbasket of libertarian adherents. 56

The consolidation of the anarchist–syndicalism in the first decades of the twentieth century created new fault lines that somewhat reinforced the effects of existing socio-spatial segregation. This unavoidably affected everything related to the management of scientific knowledge. If, until the turn of the century, the organic collaboration between the unions of Barcelona and technicians and intellectuals was permitted and even sought out, the anarchist–syndicalism that emerged after the conference of the Regional Confederation of Societies of Worker Resistance and Solidarity (Barcelona 1908) left out of its corporate structure all those who were not manual labourers. At the same time, anarchist–syndicalism distanced itself from any intellectual, or elitist, anarchism.57 What were the reasons behind this? Some of those intellectuals, like Anselmo Lorenzo, played key roles both in the cultural life of the movement and in science communication. But not all of them fitted well within anarchist ranks. That was the case of some of the young middle-class intellectuals interested in anarchism during the 1890–1910. Close to modernist literature, bearers of a Nietzschean language condemning the philistinism of the bourgeoisie, these young intellectuals were rejected because of their episodic and superficial adherence to anarchism.58 There were also criticisms of the sterility of intellectualanarchism that had settled down in Barcelona since the mid-1890s: the utility of seemingly abstruse debates was no longer evident for manual workers.59 Another prevailing argument for the exclusion of intellectuals, and with them technicians and scientists, was rooted in the distrust of workers for a sector of society from which the politicians and ‘parasites of all kinds’ were recruited.60 On the other hand, anti-dirigisme guided the new union. Workers’ emancipation ‘must not be sought in the will of others but in their own personal and collective efforts’.61

It is clear that the resolutions of the CNT congress had considerable effects on the cultural life of anarchism in the city, in part because unions, rather than small like-minded groups of libertarians, had become the hallmark of anarchist activity. In fact, the congress forced anarchist activity bifurcate into two separate spheres of action. One was the labour union membership, constituted by manual labourers and serving purely to press demands and form protests. The other sphere was made up of libertarian athenaeums and other such cultural organizations where manual and intellectual workers could collaborate to achieve the social revolution. Such organizations, along with the rationalist schools, were necessary for the syndicate’s objective of ‘promoting the intellectual culture of the worker’ and to achieve their maximum revolutionary autonomy. The impact of this strategy was also noticeable in the anarchist media. The bulletin of the CNT, Solidaridad Obrera, was used almost exclusively for revolutionary agitation and the organizational or strategic aspects thereof. Articles of science popularization or cultural interest appeared only sporadically in its pages. On the other hand, some journals and magazines intentionally incorporated such educational content (Salud y Fuerza, Generación Consciente). Other journals aimed to influence the strategic orientation of the syndicate with doctrinal articles. That was the case of La Revista Blanca, one the most important anarchist cultural journals at the time.

The consolidation of CNT in the first decades of the twentieth century brought about many changes. Propaganda and the dissemination of all kinds of knowledge reached a high point of sophistication through associative networks, which were maintained by the massive use of all forms of media and communication.62 They touched on every branch of the sciences, but obviously those having to do with subjects related to the life (and death) of workers took precedence in an organization that strived to maintain its class-based profile. As such, problems related to phenomena associated with health and sickness came to be a kind of ‘thematic’ specialty within these networks.63 The magazines Salud y Fuerza, Generación Consciente and Estudios gained prominence.64 However, as aforementioned, the relationship between anarchist–syndicalist members and experts in various branches of scientific knowledge was founded on suspicion and mistrust, basically because they were considered but another piece of the social machinery sustaining the capitalist system. The scepticism was extended to the written works of these experts. As Felipe Alaiz (1887–1959) put it, the scientific readings available at the time were ‘characterized by undiluted erudition’. That is to say, such works contained, ‘excessive allusions unintelligible to the majority of readers’. This style of writing was not an innocent professional convention; it had a cryptographic aim that seemed to endow the technician with a kind of sorcery. The technicians ‘who had degrees and titles [...] instead of socializing their knowledge, instead of making it accessible, they put it in a sack [...] available only to their familial professional dynasty’.65 What was required, was to wrest away from technicians and intellectuals the management of knowledge: a network of specialized teaching societies that, from militant eclecticism, would use knowledge retooled for the social transformation they aspired to induce.66 This network would not be limited to the reading of texts but would treat scientific knowledge like all other knowledge, always at the service of the social cause. Let us analyse some of the consequences of this approach and its significance for libertarian movement.

Self-teaching and self-management of knowledge brought into existence groups of libertarian workers with a great understanding of the topics that concerned the proletariat or had a strong social impact through their connection to health and sickness.67 Consequently, it could often be the case that the topics of some conferences were already well known by the audiences of libertarian associations. That was usually the case when the invited speaker just summarized contents of books widely available in working class associations’ libraries. Many of the reviews of these conferences, drafted by workers for the anarchist–syndicalist press, included after their description of the address a critique of its content or a section clearly pointing out what the speaker should have said before the audience. In October of 1935, Martín Zabiña commented in Solidaridad Obrera on the seminar delivered by Doctor Ramón Torra Bassols at the Fraternal Centre of Palafrugell under the title, ‘Should the people worry about the problem of venereal diseases?’ After briefly summarizing the doctor’s procedure, he continued: ‘And now, with all the respect I owe the kind lecturer, let me to direct a few comments and objections to his address’. Among these objections he emphasized the ‘deficient anatomical explanation’ as well as the doctor’s failure to explain ‘the prophylactic means to avoid infections’. Additionally, he recalled that the products recommended for the treatment of venereal diseases (mercury and silver nitrate) ‘do not cease to produce other disasters in the body that, sometimes, are worse than the disease itself’. The reviewer justified his critique in didactic terms: the lecturer was informed that, if having the opportunity to address them again, anarchists would expect to ‘listen for those aforementioned parts that we deem essential to the character of such seminars’.68

As we can see, anarchist–syndicalists had their own ideas about what was ‘proper’ to disseminate given the ‘character’ of the seminars. This shows that the libertarian audiences were not prone to passively accepting hegemonic knowledge. They rather had a truly different interpretation of concepts that, in many cases, had undergone a process of appropriation and development independent of the ‘official’ theories. Anarchist–syndicalists also maintained discrepancies with intellectuals belonging to other subaltern groups if the positions they held did not fit with libertarian interests. That was the case with naturism, widely popular among subaltern groups of various ideological persuasions at that time. In 1935 José Castro (1890–1980) offered a seminar at the Casa del Poble of La Cenia (in Tarragona) under the title ‘What and How should Humanity Eat?’ The reviewer, J. Balada, affirmed in the Solidaridad Obrera that, Castro, ‘fully convinced that he is doing good work, works by means of speaking and writing, in favour of trophology naturism’. But he criticized the fact that Castro had declared liberty to be a branch of naturism, when, in reality, liberty was, ‘the base of all things’. Balada recognized the existence of a multitude of naturist groups and accepted certain coincidences with the ideas they defended but concluded by insisting that, ‘our concept of naturism differs greatly from that of the large majority of those other groups’.69

This way of managing scientific knowledge did not limit itself to the correction or rebuttal of opposing ideas to reassert its ideology, but it also allowed the use of traditional forms of communication to reverse the order of the message, transcending the functions of ‘self-formation’ and ‘cultural extension’ attributed to the anarchist cultural centres.70 We are thinking on the use of the lecturer himself as a mean of propaganda. In 1916, José Salvat wrote in Solidaridad Obrera about a lecture on syphilis that had taken place at the Labour Centre in Mercaders Street, Barcelona. He complained that it had ‘made an impression only on the conscious men’, already aware of the social problem represented by this disease. However, Salvat underlined that the event had not been in vain. The lecturer, Dr Marsal, was satisfied with how well received his talk had been by a ‘nucleus of workers that, with outstanding consideration, were able to show respect to people who, uninterestedly, helped instruct the working class’. The recipient of the message were not the workers coming to listen or learn, but the lecturer himself, in this case a doctor who had unintentionally turned into an instrument of communication supporting the interests of anarchism. This was the core idea behind Salvat’s proposal to organize this type of events en masse:

[...] this will result into more lecturers and a more solid relation with doctors, lawyers and other men representing different fields of knowledge. Studying our way of acting and thinking, they will approve with their presence the cultural work accomplished in the Labour and Social Studies Centres, refuting the bureaucracy whose only tendency is the devaluation of our work through defamation, portraying us to uneducated and unaware people as criminals who shall be fought.71

This use of scientific knowledge supports the image shown by Felipe Alaiz in 1933 in Solidaridad Obrera. According to it, ‘the majority of technicians, professors, journalists, engineers and doctors’ did not know the full works of anarchist thinkers because they lived in the ‘world of the books’, whose academic contents portrayed anarchism as a utopia, and considered the ‘free association and assistance outside the State absurd’. However, it was contradictory, according to Alaiz, that the workers looked at holders of university degrees with fear, even when ‘he had read less than them’.72 The practices and strategies of communication about the spread of scientific knowledge, in the cases that we have presented, would act like mechanisms of social inclusion/exclusion according to the interests of the parties involved.73 For Alaiz, this contradiction could be explained by the fact that ‘a graduate is enclosed in a system’. This ‘system’, as clearly stated in his article, would be a mechanism of the state to legitimize the expert’s superiority regardless of their knowledge. It would coincide with the ‘bureaucracy’ previously denounced by Salvat, contributing to the spread of a false image of the anarchists.

Holding a university degree legitimized the holder with scientific authority against the body of knowledge that a manual self-taught worker could have accumulated. Denouncements of this situation were employed in anarchist media to highlight the contradictions of the capitalist system, especially when libertarian cultural centres were shut down, accused of training violent revolutionaries. In 1933, in the midst of political repression against the libertarian cultural centres, Solidaridad Obrera claimed that, ‘the social level of the proletariat was the result of the work of syndicates and athenaeums, not of the State’, and that it was frequently ignored that, ‘every one of the men of the athenaeums knows more about hygiene, physiculture and heliotherapy than ninety per cent of rural teachers’.74 In fact, individuals educated and trained for the good of the community, possessing a cultural level similar or superior to the graduates, were usually represented as criminals. Workers conscious of this problem felt rage and indignation. In Solidaridad Obrera it was related how a mailman asked an inspector at ‘Patria’, a benefit society for the sick, how he could be compensated for the sickness and death of his wife. The doctor of the society had concluded that the wife had died of a stomach ulcer and that, since it was a chronic illness, it did not merit any economic compensation. The mailman answered: ‘I assure you, Sir, that no sickness can be chronic that did not exist before she fell sick on this occasion, and it is demonstrable that in one month she was both healthy and dead! Is a sickness “chronic” that lasts for one month? That’s what the doctors and the Rulebook will say, but I say otherwise’. Faced with this question, the inspector, ‘with a strong voice and a scornful expression, at the same time leaving’, answered: ‘You’re a mailman! You have no right to discuss these things!’ The denouncement concluded: ‘What was this “inspector” trying to say with those intentionally hurled provocations? [...] I tell you from here that I am a “mailman” and I consider myself at least as dignified as him, or more.’ 75

The dignity acquired by manual labour was strengthened and justified, in anarchist ideology, by the cultural dignity procured by the acquisition of technical knowledge. This helps us understand the impact of popular science magazines on the working class. It also explains the need to seek out forms of direct communication, such as the ‘Questions and Answers’ sections, a format used to elaborate the daily schedule of plenary sessions and congresses of the unions of the CNT.76 But the recuperation of the real experiences of the various audiences is still a challenge.77 It is certain that anarcho-syndicalism put questions directly to the working class, and that direct channels of communication were launched. But did these communication practices go beyond the limits of self-taught workers or politically informed militants? Tensions might have been created when anarchists tried to popularize readings of what is ‘scientific’, ‘rational’ or ‘healthy’.78 The anarchist propagandists did not work upon a tabula rasa, but on individuals and groups with their own cultural traditions. It could not be taken for granted that anarchist’s alternative readings of scientific theories would find, always and everywhere, a fertile reception among the fragmented and divided working class of Barcelona.

In 1929 it was clear that the libertarian management of science was deeply affected by the creation of a social abyss within Barcelona. The old alliance between anarchists, federal republicans and freemasons was no longer operational. The geography of communication was modified by the explosive growth of the city and libertarians created a network adapted to the new realities. In 1888 suspicion about the bourgeois character of the science produced by scientists and technicians was emerging. In the 1920s it was almost systemic, reflecting both the class-based orientation of anarchist–syndicalism and the tough reality of a divided city. But this is not the only consideration we should take into account: imaginary spaces are important too. Anarchists sought to mobilize a working class that lived, almost without exception, in a miserable situation. Segregated from the rest of the city, the workers of this ‘modern’ Barcelona had few reasonable expectations of ascending the social hierarchy. General statistics reflect a partial improvement over time (a decrease in the mortality rate, for example) but the vast majority of immigrants who arrived in the city in the 1920s had, as the sole horizon of their lives, improvised neighbourhoods with horrifying living conditions. Part of the attraction of anarchism resided precisely in its utopian character: it enabled thinking about the possibility of a different world, new and radically distinct from the devastating visible reality. What’s more, anarchism puts ‘on trial that which currently exists’; it creates a ‘contingency of order’.79 If the real Barcelona was a hostile space, a true prison for workers, anarchism provided an escape route.

The anarchist utopia, like many other utopias, tried to be rational. Consequently, science acquired a prominent role. However, the following non-trivial fact must not be forgotten: the recreational character of science. In the science sections of anarchist newspapers and magazines of Barcelona, topics as disparate as malaria, the investigations of Marie Curie and aerial navigation were discussed. Many times they were treated as apparently aseptic objects of science popularization, far from any immediate political utility. But they were about something else: apart from contributing to the formation of the self-taught worker, the reading of scientific texts became the ideal type of entertainment. It allegedly took workers away from the stupefying effects of gambling or drinking and was different from other highly questionable regimes of pleasure.80 Not all is about honest entertainment. The anarchists spoke of the right to life, not only in the sense of a right to the basic means of subsistence but also meaning that society was obliged to offer satisfaction to all vital necessities. Scientific popularization is not only a way of returning a good expropriated by the bourgeoisie (that is, science); it is also an essential element for the development of a truly full life. Put that way, popular science usually evoked spaces quite distinct from the gloomy alleys of the run-down areas of the old city, the cotton factories or the neighbourhoods presided over by the ominous shadow of factory chimneys. The reading of scientific texts opened escape routes through imaginary spaces: the infinite cosmos, microscopic organisms and other marvels and mysteries of the universe.

1The critical remarks made by the referees, José Álvarez-Junco and Chris Ealham, have been instrumental for improving this chapter. The research made has been financed by the Spanish Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad through the research projects, ‘Science and the city. Natural history, biology and biopolitics in the divided city: Barcelona and Buenos Aires (1868–1936)’ (HAR2013–48065-C2–1-P) and ‘Health, illness and social order in Spain. The social inclusion-exclusion dynamics based on class and profession through medical discourses and practices in the 20th century’ (HAR2009–13389-C03–01).

2Angel Smith (ed.), Red Barcelona. Social Protest and Labour Mobilization in the Twentieth Century (London/ New York: Routledge, 2002).

3Josep Termes, Historia del anarquismo en España (1870–1980) (Barcelona: RBA, 2011), pp. 113–18.

4Eduard Masjuan, La ecología humana en el anarquismo ibérico. Urbanismo ‘orgánico’, neomaltusianismo y naturismo social (Barcelona: Icaria, 2001), pp. 57–60.

5 Joaquín Romero Maura, ‘La rosa de fuego’. El obrerismo barcelonés de 1899 a 1909 (Madrid: Alianza 1989), pp. 140–1.

6 This could also be tied to the articulation in Barcelona of an urban public sphere of proletarian provenance. See Chris Ealham, La lucha por Barcelona. Clase, cultura y conflicto (Madrid: Alianza 2005), pp. 78–104.

7 Daniel P. Todes, Darwin without Malthus. The Struggle for Existence in Russian Evolutionary Thought (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), pp. 123–42.

8 José Álvarez Junco, La ideología política del anarquismo español (1868–1910) (Madrid: Siglo XXI, 1991), pp. 65–92.

9 Álvaro Girón Sierra, En la mesa con Darwin. Evolución y revolución en el movimiento libertario español (1869–1914) (Madrid: CSIC, 2005).

10Eduard Masjuan, ‘Procreación consciente y discurso ambientalista: anarquismo y neomalthusianismo en España e Italia, 1900–1936’, Ayer, 46 (2002): 63–92; Richard Cleminson, Anarchism, Science and Sex: Eugenics in Eastern Spain, 1900 (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2000).

11Jorge Molero-Mesa and Isabel Jiménez-Lucena, ‘“Otra manera de ver las cosas”. Microbios, eugenesia y ambientalismo radical en el anarquismo español del siglo XX’, in Marisa Miranda and Gustavo Vallejo (eds), Darwinismo social y eugenesia. Derivas de Darwin: cultura y política en clave biológica (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2010), 143–64.

12Jaume Navarro, ‘Los educadores del pueblo y la revolución interior. La cultura anarquista en España’ in Julián Casanova (ed.), Tierra y libertad. Cien años de anarquismo en España (Barcelona: Crítica, 2012), 191–217, p. 192.

13José Álvarez Junco, Alejando Lerroux. El Emperador del Paralelo (Madrid: Síntesis, 2005), p. 169.

14Rafael Núñez Florencio, ‘El terrorismo’, in Julián Casanova (ed.), Tierra y libertad. Cien años de anarquismo en España (Barcelona: Crítica, 2012), 61–87.

15Girón, En la mesa con Darwin, p. 21.

16Susana Tavera, ‘La historia del anarquismo español: una encrucijada interpretativa nueva’, Ayer, 45 (2002): 13–37.

17José Álvarez Junco, ‘La filosofía política del anarquismo español’, in Julián Casanova (ed.), Tierra y libertad. Cien años de anarquismo en España (Barcelona: Crítica, 2012), 11–31, pp. 25–6.

18Álvarez Junco, ‘La filosofía política del anarquismo español’, pp. 16–17.

19José Álvarez Junco, ‘La subcultura anarquista en España: racionalismo y populismo’ in Yves-René Fonquerne and Alfonso Esteban (eds), Culturas populares. Diferencias, divergencias, conflictos (Madrid: Universidad Complutense, 1986), 197–208, p. 198.

20Pere Gabriel, ‘Republicanismo popular, socialismo, anarquismo y cultura política obrera en España (1860–1914)’, in Javier Paniagua et al., Cultura social y política en el mundo del trabajo (Valencia: Fundación Instituto de Historia Social/UNED, 1999), 211–22, p. 220.

21Álvarez Junco, La ideología política del anarquismo español, p. 203.

22Romero Maura, ‘La rosa de fuego’, p. 193.

23Anselmo Lorenzo, ‘Incapacidad progresiva de la burguesía’, La Revista Blanca, 145 (1904): 1–7, p. 2.

24Carlos Serrano, ‘Cultura popular/cultura obrera en España alrededor de 1900’, Historia social, 4 (1989): 21–31.

25Michel de Certeau, L’invention du quotidien. I. Arts de faire (Paris: Gallimard, 1990), pp. 244–5.

26Carlos Tabernero, Isabel Jiménez-Lucena and Jorge Molero-Mesa, ‘Libertarian movement and self-management of knowledge in the Spain of the first third of the 20th century: “Questions and answers” section (1930–1937) of the journal Estudios’, Dynamis, 33 (1) (2013): 43–67.

27Anselmo Lorenzo, ‘Ciencia burguesa y ciencia obrera’, Acracia, 22 (1887): 354–9, p. 355.

28Richard D. Sonn, Anarchism & Cultural Politics in Fin de Siècle France (Lincoln/London: University of Nebraska Press, 1989), pp. 51–2.

29George Esenwein, Anarchist Ideology and the Working-Class Movement in Spain, 1868–1898 (Berkeley: University of Califonia Press, 1989), pp. 130–5.

30Agustí Camós, ‘Darwin in Catalunya: From Catholic Intransigence to the Marketing of Darwin’, in Eve-Marie Engels and Thomas Glick (eds), The Reception of Charles Darwin in Europe (London/ New York: Continuum, 2008), pp. 400–12.

31Robert J. Richards, The Tragic Sense of Life. Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), pp. 312–18.

32Daniel Becquemont, Darwin, darwinisme, évolutionnisme (Paris: Editions Kimé, 1992), pp. 144–9.

33Diego Núñez, El darwinismo en España (Madrid: Castalia, 1977), p. 56.

34Antonello Lavergata, ‘Les bases biologiques de la solidarité’, in Patrick Tort (ed.), Darwinisme et société (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1992), 55–87.

35Álvaro Girón, ‘The Moral Economy of Nature. Darwinism and the Struggle for Life in Spanish Anarchism (1882–1914)’, in Thomas F. Glick et al. (eds), The Reception of Darwinism in the Iberian World (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2001), 189–203.

36‘La loi de la force et le concert pour l’existence’, Le Révolté 9 (7–13 May 1887): 1.

37Álvaro Girón Sierra, ‘¿Anarquía y darwinismo? Piotr Kropotkin en España (1882–1914)’, in Gustavo Vallejo and Marisa Miranda (eds), Políticas del cuerpo. Estrategias modernas de normalización del individuo y la sociedad (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2007), 171–98, pp. 178–81 and p. 186.

38Ibid., pp. 191–8.

39On collective reading among workers, see: Jean-François Botrel, ‘Teoría y práctica de la lectura en el siglo XIX: el arte de leer’, Bulletin Hispanique, 100 (2) (1998): 577–90.

40Roger Chartier, El mundo como representación (Barcelona: Gedisa, 1996), p. 138.

41Juan Suriano, Anarquistas. Cultura política libertaria en Buenos Aires, 1890–1910 (Buenos Aires: Manantial, 2001), p. 117.

42Louis Dramard, ‘Transformisme et socialisme’, La Revue Socialiste, 1 (1885): 24–39.

43Esenwein, Anarchist Ideology, p. 124.

44Álvarez Junco, Alejandro Lerroux, pp. 337–42.

45Jacqueline Lalouette, La libre pensée en France, 1848–1940 (Paris: Albin Michel, 2001).

46Albert Palá Moncusí, ‘Sociabilité et libre-pensée en Catalogne (1860–1909) in Séminaires du CRIDAF 2004–2005: La sociabilité dans tous ses états (2004), p. 2 and pp. 12–13, http://www.univ-paris13.fr/CRIDAF/TEXTES/PalaLibPens.pdf (last accessed May 2014).

47La Federación, 14 November 1869, 2.

48Álvaro Girón Sierra, ‘Una historia contada de otra manera: librepensamiento y ‘darwinismos’ anarquistas en Barcelona, 1869–1910’, in Clara Lida and Pablo Yankelevich (eds), Cultura y política del anarquismo en España e Iberoamérica (México: El Colegio de México, 2012), 95–133, pp.117–19.

49Gerard Horta, Cos i revolució. L’espiritisme català o les paradoxes de la modernitat (Barcelona: Edicions de 1984, 2004). On spiritism in Barcelona also see Chapter 7 in this book.

50Stefan Pohl-Valero and Favio Cala Vitery, ‘Energía, entropía y religión. Un repaso histórico’, Revista de la Academia Colombiana de ciencias exactas, físicas y naturales, 34 (130) (2010): 37–52.

51Fernando Tarrida del Mármol, ‘El espiritismo’, La Luz, 21 (1886): 4–5.

52Álvaro Girón, ‘Los anarquistas españoles y la criminología de Cesare Lombroso (1890–1914)’, Frenia 2 (2) (2002): 81–108.

53See: Juan Avilés Farré, ‘Republicanismo, librepensamiento y revolución: la ideología de Francisco Ferrer Guardia’, Ayer, 49 (2003): 249–70.

54Agustí Nieto-Galan, ‘A republican natural history in Spain around 1900: Odón de Buen (1843–1945) and his audiences’, Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 42 (3) (2012): 158–89, pp. 174–9.

55Ealham, La lucha por Barcelona, p. 45.

56José Luis Oyón, La quiebra de la ciudad popular. Espacio urbano, inmigración y anarquismo en la Barcelona de entreguerras, 1914–1936 (Barcelona: Ediciones del Serbal, 2008), p. 444.

57Antonio Bar, La CNT en los años rojos: del sindicalismo revolucionario al anarcosindicalismo, 1910–1926 (Barcelona: Akal, 1981), pp. 102–5 and pp. 128–9. On relations between the CNT and technicians and scientists, see: Jorge Molero-Mesa and Isabel Jiménez-Lucena, ‘“Arm and brain”: Inclusion-exclusion dynamics related to medical professional within Spanish anarcho-syndicalism in the first third of the 20th century’, Dynamis, 33 (1) (2013): 19–41.

58This occurred in Barcelona, but something very similar happened in Buenos Aires and Paris: Suriano, Anarquistas, p. 133.

59Romero Maura, ‘La rosa de fuego’. El obrerismo barcelonés de 1899 a 1909, pp. 240–1.

60Bar, La CNT en los años rojos, p. 547.

61Congreso de Constitución de la CNT (Barcelona 30 October–1 November 1910), http://archivo.cnt.es/Documentos/congresosCNT/CONGRESO_CONSTITUCION_CNT.htm (last accessed October 2014).

62Javier Navarro Navarro, A la revolución por la cultura: prácticas culturales y sociabilidad libertarias en el País Valenciano (1931–1939) (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2004).

63Josep Lluís Barona, ‘Ciencia y revolución en la España de Martí Ibáñez’, in José Vicente Martí and Antonio Rey (eds), Actas del I Simposium Félix Martí Ibáñez: medicina, historia e ideología (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 2004), 17–38.

64Francisco J. Navarro, El paraíso de la razón. La revista Estudios (1928–1937) y el mundo cultural anarquista (Valencia: Edicions Alfons el Magnànim, 1997).

65[Felipe Aláiz], ‘La escuela y el libro. [Libros de técnica y técnica de libros]’, Solidaridad Obrera, 29 July 1933.

66Isabel Jiménez-Lucena and Jorge Molero Mesa, ‘Problematizando el proceso de (des)medicalizació. Mecanismos de sometimiento/autogestión del cuerpo en los medios libertarios españoles del primer tercio del siglo XX’, in Marisa Miranda and Álvaro Girón Sierra (eds), Cuerpo, biopolítica y control social: América Latina y Europa en los siglos XIX y XX (Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI, 2009), 69–93; Isabel Jiménez-Lucena and Jorge Molero-Mesa, ‘Good birth and good living. The (de)medicalising key to sexual reform in the anarchist media of inter-war Spain’, International Journal of Iberian Studies, 24 (3) (2011): 219–41.

67Social medicine was among the topics most frequently debated in libertarian athenaeums: Anna Monjo, Militants. Participació i democracia a la CNT als anys trenta (Barcelona: Laertes, 2003), p. 380.

68Martín Zabiña, ‘Una conferencia. Objeciones’, Solidaridad Obrera, 1 October 1935.

69J. Balada, ‘Propaganda naturista’, Solidaridad Obrera, 29 March 1935. The italics are ours.

70Javier Navarro Navarro, ‘El papel de los ateneos en la cultura y la sociabilidad libertarias (1931–1939): algunas reflexiones’, Cercles, 8 (2005): 64–103, p. 95.

71José Salvat, ‘El Dr. Marsal en el Centro obrero’, Solidaridad Obrera, 27 December 1916. The italics are ours.

72[Felipe Aláiz], ‘La cuestión de los intelectuales’, Solidaridad Obrera, 2 November 1933.

73Jorge Molero-Mesa and Isabel Jiménez-Lucena, ‘(De)legitimizing social, professional and cognitive hierarchies. Scientific knowledge and practice in inclusion-exclusion processes’, Dynamis 33 (1) (2013): 13–17.

74‘Otra vez los bárbaros. Peligran las escuelas racionalistas’, Solidaridad Obrera, 30 June 1934.

75Juan Catalán, ‘Patria’, Solidaridad Obrera, 8 March 1917.

76Tabernero, Jiménez-Lucena and Molero-Mesa, ‘Libertarian movement and self-management’, p. 51.

77See: Jonathan Topham, ‘Beyond the ‘Common Context’: The production and reading of the Bridgewater Treatises’, Isis 89 (2) (1998): 233–62; Jonathan Topham, ‘Rethinking the History of Science Popularization/Popular Science’, in Faidra Papanelopoulou, Agustí Nieto-Galan, and Enrique Perdiguero (eds), Popularizing Science and Technology in the European Periphery, 1800–2000 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009), 1–10.

78On social-democratic readings of Darwinism, see: Kelly, The Descent of Darwin, pp. 135–41.

79Paul Ricoeur, Ideología y utopía (Barcelona: Gedisa, 1989), pp. 315–6.

80Amparo Sánchez Cobos, ‘Sociabilidad anarquista y configuración de la identidad obrera en Cuba tras la independencia’, in Clara Lida and Pablo Yankelevich (eds), Cultura y política del anarquismo en España e Iberoamérica (México: El Colegio de México, 2012), 219–58, p. 230.