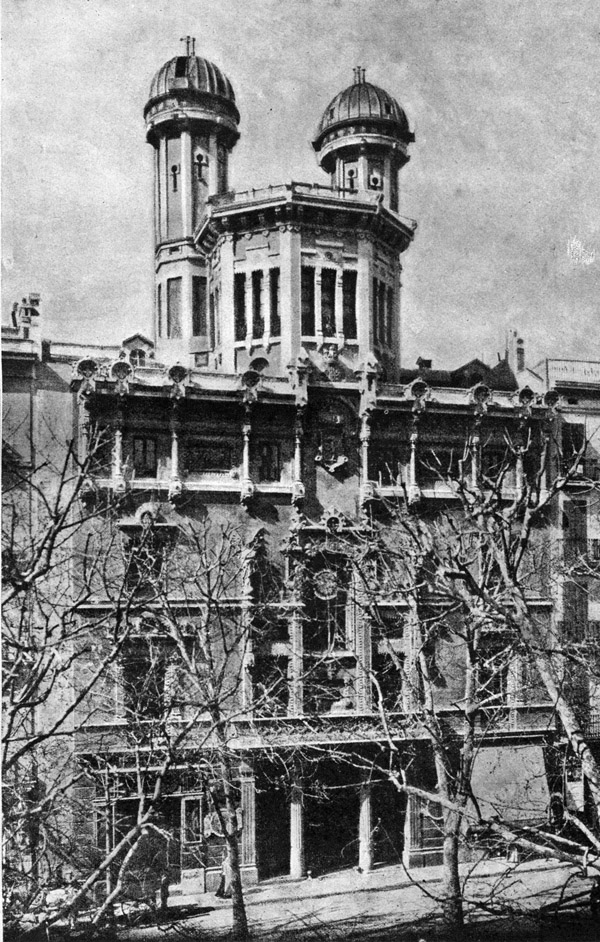

Figure 9.1 Photograph of the RACAB building with its two towers, 1914.

Josep Comas i Solà (1868–1937), the highly renowned Catalan astronomer, died on 2 December 1937 in Barcelona, while the city was suffering the horrors of the Spanish Civil War; in particular, the bombardments by the Italian Fascist Aviation on the civilian population. Despite this desperate situation, the whole city came out to honour its local hero. His public funeral became an impressive tribute to a man who had ‘placed’ the name of Barcelona in the heavens, after his discovery of a minor planet – orbiting the Sun in the Asteroid belt – that was named after the city.2 The ceremony was presided over by local political authorities who accompanied the funeral procession, together with the municipal police force and the city brass band. There were also representatives of the military and of different media – newspapers and periodicals for the general public, scientific journals and radio stations – and leaders of different cultural and educational institutions, union members, students and the general public.3

Comas i Solà had pursued his scientific career by combining highly technical astronomical observations with a successful popularization programme. Between 1915 and 1930 he discovered 11 asteroids, which led to a general recognition of his scientific excellence.4 Much of his astronomical research was conducted at the Fabra Observatory, one of the most relevant sites for astronomical observation that were created in Barcelona during these years. Since Comas i Solà was the director of the observatory, it soon became an urban site for conveying credibility, authority and expertise. Comas i Solà was convinced that astronomy – and science in general – was a useful and versatile cultural resource to transmit moral values and improve society. His popularization programme led him to collaborate on a regular basis with the newspaper La Vanguardia, in which he published weekly popular science articles from 1893 to his death. From bourgeois to working-class audiences, he was also an active public lecturer in cultural societies and institutions.

The case of Comas i Solà is particularly useful for depicting the important role of science – and more specifically astronomy – in Catalan and Spanish culture during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Furthermore, it may be used to analyse how local scientists shaped the social, political, economic and cultural values of the city. At the same time, the city influenced the development of astronomy, which was based on a set of regimes of observation and circulation of knowledge that included new discourses and forms of social organization. In urban spaces like the Fabra Observatory, metropolitan science was not only a form of knowledge and a matter of technical sophistication, but also a practical activity that involved the management of educational and civic spaces in the city.5

The history of Barcelona during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century cannot be written without taking into account the role of astronomy, and neither can the emergence and development of astronomy in the city be understood without considering the local context and the urban public. To this end, several facets of astronomical practice will be addressed regarding the creation of several observational sites and amateur societies, as well as the development of a programme for the popularization of astronomy that was particularly useful for the discipline of citizens in a growing industrial city.

The professional status of astronomy in Barcelona during the second half of the nineteenth century was controversial. As the forestry engineer Rafael Puig i Valls bitterly complained in an article published in La Vanguardia, the university had no chair devoted to the subject and only one cabinet of topography and geodesy with a small telescope and some theodolites and tachymeters, while the Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona (Royal Academy of Sciences and Arts of Barcelona, RACAB) possessed only some damaged astronomical instruments.6

However, the RACAB managed to play a crucial role in the development of astronomy and meteorology in the city.7 The exceptional events of the mid-nineteenth century – the solar eclipses of 1842, 1850 and 1860 – attracted the interest of some fellows of the Academy such as Onofre Jaume Novellas and Llorenç Presas.8 Later, in 1883, under the presidency of the military officer and mathematician Angel del Romero, the RACAB strove to renew its activities. This led to a refurbishment of its building, which included a natural history cabinet and the transformation of the roof into an astronomical and meteorological observatory.

The creation of these new observational sites was perceived by the local elites as particularly necessary. On the one hand, astronomy had proved useful for the unification of time all over the world, which had a great impact on the development of railway networks during the second half of the nineteenth century.9 Meteorology, on the other hand, was particularly relevant for public health issues, mainly in the cities. Therefore, Catalan cultural elites were keen to build such observatories. As they saw it, all important cities and intellectual centres abroad had such institutions, which offered a very useful service to citizens.10 This agenda may well be identified with the spread of a heterogeneous regenerationist movement throughout Spain. This movement, which was a legacy of nineteenth-century Spanish liberal ideas, sprang up during the last quarter of the century and figured largely in the press, literature and art.11 Also known in Spain as Europeanization, its aim was to emulate successful initiatives from abroad for the modernization of the country.

In 1883, the RACAB appointed José Joaquín Lánderer (1841–1922) to serve as supervisor of the new observatories. The astronomical observatory had to include an official time service, while the meteorological observatory had to coordinate a Catalan network of climatological stations in the region. An amateur scientist in several fields, mainly geology and astronomy, Lánderer was born in Valencia and lived in Tortosa, in the South of Catalonia, where he was a landowner.12 Being a member of several societies, he was fully integrated into the European community of amateur astronomers. Lánderer’s project was ambitious and covered not only astronomy and meteorology, but also some fields of geophysics, telluric currents and earth magnetism. In accordance with his plans, some instruments were purchased in France. Nevertheless, the building work on both observatories suffered delay and Lánderer resigned from his position.

The project had been partly funded by the Diputació de Barcelona (Barcelona Provincial Council) and the City Council.13 Both institutions urged the RACAB to find a way of organizing the scientific services they intended to provide. The Academy asked one of its members, Josep Ricart Giralt, for the use of his chronometric office for the time service. Thus, in 1890, the new official time service in Barcelona was established to deal with the determination and unification of civil time.14 A few years later, after the building was eventually opened, observations and calculations were conducted at the RACAB. In this new context, the Academy appointed Eduard Fontserè (1870–1970) to be in charge of the observatory, just after he had submitted his doctoral thesis in physics.15

The astronomical and meteorological services were finally set up in 1894 on the roof terrace of the RACAB on the Rambla, the famous boulevard in the heart of Barcelona – considered a centre of urban life.16 The new RACAB building had two towers to be used as an observatory: one for the meridian circle – to determine the path of stars at the local meridian in order to calculate local time – and another for the equatorial telescope – for astronomical observations in general. Nevertheless, during the decade that elapsed between the initial project and the completion of the observatory, circumstances had changed dramatically. The extension of telegraph lines, electric lighting and pollution had all grown considerably in the city, creating adverse conditions for astronomical observations and even worse conditions for geophysical measurements.

As David Aubin pointed out, the modernization of Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century clashed with the increasing precision required for astronomical studies in the observatory of the city.17 This led to an intense public debate regarding the possibility of moving the observatory outside the city to preserve isolation from noise, dirt, temperature gradients, vibration and lighting. Thus, the growth of modern cities seemed to affect the ideal of precision required for astronomical observations, in which the high sensitivity of astronomical instruments played a crucial role. The astronomical culture of high precision was closely related to the determination and unification of time, regarded as a crucial issue for the correct social functioning of cities, and Barcelona was no exception. In fact, some authors complained about how, despite the fact that the RACAB provided the general public with a standard mean time, the lack of a unified time in the city reflected ‘the anarchy that ruled in Barcelona’.18

The city needed a properly equipped astronomical observatory. But where should it be placed? Barcelona lies on the Mediterranean coast and is surrounded by the mountains of the Serra de Collserola. Such a peculiar topography clearly influenced the decision. The highest point was the Tibidabo hill, an exceptional location for a new observatory, as the air was much cleaner than in the city centre. Tibidabo had acquired a very popular image during the 1888 Universal Exhibition, when a provisional construction was erected there for the visit of the Queen, and several official excursions were organized.19

The idea to set up a new observatory was discussed during the last decades of the nineteenth century. There is evidence that it was debated in informal meetings of several RACAB members at the workshop of the watchmaker Adolf Juillard. Fontserè, who used to attend these tertulias or casual get-togethers, was officially requested by the RACAB to devise a project for the new observatory. He designed an astronomical, meteorological and seismological observatory to promote scientific services, including the official local time service, a meteorological service to study regional meteorology and to establish weather forecasting, and a seismological service to study the seismicity of Catalonia.

The project for the new observatory on top of the Tibidabo hill became a topic of general interest that was reported and discussed in the local press. Blueprints of the project appeared in newspapers.20 Yet not everybody agreed; some local experts claimed that meteorological observatories in the heart of the old city were especially useful. They would provide data of the atmosphere that could be related to hygienic conditions – and therefore had to be obtained from the environment in which people lived. In that sense, the meteorological observatories located at the University of Barcelona and the Experimental Agricultural School were to prove more effective.21 Therefore, while some supported the Tibidabo project, others argued against such an initiative, which was not considered to be of priority, given the urgent need for a modern sewage system and new schools for children.22

Finally, the project of the new so-called Observatory of Barcelona was submitted to the Diputació in 1895. Although promoters of the observatory were convinced that private support would also be necessary, its institutional backing was crucial.23 The Diputació, however, did not approve any subsidy for the new observatory, as there was no guarantee of either the local council or any private initiative being financially involved.24 Moreover, the Provincial Council regarded Tibidabo as the ideal place for the construction of an expiatory church, a tribute paid by the owners of the mountain to the Italian priest John Bosco for his visit to Barcelona in 1886. Nevertheless, the RACAB pursued the project while seeking further support.

From a scientific point of view, the Tibidabo hill seemed to be the best location for the new observatory. It had been redefined during the last decade of the nineteenth century, and had become a symbol of the ambitions of the Catalan bourgeoisie, particularly in terms of how modernity should be incorporated into the city. This perception also influenced the final decision to set up a new observatory there. Similarly to what George Wise has noted for Albany’s Dudley Observatory, the new observatory had to become ‘an attempt at civic astronomy’, a place to understand the heavens and to proclaim the city’s proud place in the world – a site to see from and a spot to be seen.25

In other words, the Tibidabo hill was not only included as part of the city, but also became the centre of a new urban and metropolitan identity promoted by the upper classes and intellectual elites of Barcelona. It became a symbol of modernity and the place where several cutting-edge innovations were introduced, including the first cable railway, in an attempt to promote a new image of the city. As Garriga Bosch pointed out:

Tibidabo was a reason of pride and prestige and an opportunity for political, religious, scientific, cultural and social promotion. The identity shaped was … a deliberate task of construction and assimilation of a new urban and social attitude … that channelled the ideals of a society devoted to the introduction of modernity into the city … The conquest of Tibidabo was in the social imagination a symbol of the modern expression of the city and of the ambition of the bourgeois classes.26

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, the upper classes of Barcelona had already found a ‘natural’ space on the lower mountainside of the Tibidabo hill to be used not only for second residences, but also for the organization of private events.27 This new urban model constituted an intelligent and rational urban development, in which the management of transport, leisure and health issues played a central role.28

The Sociedad Anónima El Tibidabo company was in charge of urbanizing the hill and setting up a tram and a cable railway, the latter being the first one in Spain, which was officially opened in October 1901. This initiative was part of a larger project and was presented as a crucial element for the growth and progress of the city:

It seems pointless to exhort the advantages that, in every respect, the rail and the urbanization of the hill must provide to the people of Barcelona [...] The work that has been done here is great, immense, not only from a hygienic, but also from a moral point of view; it is, indeed, mainly an educational and moral act.29

Thus, the construction of an astronomical observatory on top of the Tibidabo hill formed part of a broader and more ambitious enterprise. Urbanization had rendered astronomical observations increasingly difficult, forcing observatories to move to distant and isolated locations. However, in Barcelona, it opened up new possibilities for astronomical studies not far from the city centre.

In 1902, Camil Fabra (1833–1902), a textile entrepreneur and former mayor of Barcelona, made a private donation to the RACAB to secure the construction of the observatory.30 Therefore, a new name was given to the projected observatory to honour the donor, who died the same year. After a period of complaints about the slowness of the works,31 the Fabra Observatory was finally inaugurated in 1904. Following Eduard Fontserè’s original plan, a design was created by the architect Josep Domènech Estapà (1858–1917), who was also member of the RACAB and had been in charge of the restoration of the building of the Academy.32 The historicist architecture he developed was similar to that of other Spanish observatories erected during these years – such as the Cartuja Observatory, founded in 1902.33 In fact, the neoclassical elements shared by these observational sites may be understood as an attempt to gain credibility and authority from the Royal Observatory of Madrid, the main astronomical institution in Spain – established in 1790 and one of the masterpieces of Spanish neoclassical architecture.34

Despite his rejection of ‘modernism’,35 Domènech Estapà was one of the most influential architects in Barcelona. He was known for his eclecticism. Amongst his constructions one can find the Palace of Justice, built for the 1888 Universal Exhibition; the Cárcel Modelo (Model Prison); the Clinic Hospital; and the Faculty of Medicine. Therefore no one questioned his ability to carry out the project he had originally helped to conceive.36 Fontserè, however, was marginalized. In fact, the directorship of the new observatory was left in the hands of Comas i Solà.

Comas i Solà had been elected to the RACAB in 1900. He was a very active astronomer and had published his observations in several specialized international journals. In the previous decade, Comas i Solà and Fontserè had been close friends while undergraduates at the Science Faculty of the University of Barcelona, but they followed different paths in life. Fontserè held a modest position in the RACAB while trying to become a professor at the university, a position he finally achieved in 1900. He was only elected as a member of the RACAB in 1909. Comas i Solà, on the other hand, had accepted a position as an astronomer at a private observatory in Sant Feliu de Guíxols, on the north coast of Catalonia. Comas i Solà’s family was wealthy and he finally decided to leave his position in Sant Feliu and return to Barcelona, where he continued his astronomical activity in a private observatory set up at his home, named Vil·la Urània, and where he made important observations of Mars and Jupiter, as well as of asteroids, comets and other celestial bodies.

The directorship of the new astronomical observatory was an exceptional opportunity for Comas i Solà. The Fabra Observatory was to host the most powerful equatorial telescope in Spain. Moreover, Comas i Solà was also to form a research group, probably the earliest in the exact sciences in Barcelona. Many of the discoveries he made – including the minor planets – required an accurate analysis of photographic plates and calculations, and in the 1920s the Fabra Observatory contracted the physicists Joaquim Febrer (1893–1970), Isidre Pòlit (1880–1958) and the mathematician Assumpció Serret (1894–1934) to deal with this work.37

The Fabra Observatory had to be built on top of a hill that was now fully integrated into the city and could easily be reached by the cable railway. Comas i Solà therefore had the opportunity to develop a programme here for the popularization of astronomy, which would put the new observatory at the centre of scientific sociability, making it a central site for the cultural and intellectual life of the city – not unlike what had occurred at the Paris Observatory in the nineteenth century.38 Indeed, Comas i Solà’s scheme to popularize astronomy at the Fabra Observatory became a success. According to him it even transcended class barriers:

The poorest social classes have so far taken a very active part in this wonderful scientific movement [...] On the days of public lectures, under the great equatorial dome of the Observatory, one may see there many people of both sexes from all social classes showing deep respect for the event, the feeling of fraternity among the audience, the good manners and behaviour of all without exception, and the huge interest they all show for what they hear and see.39

Astronomy had captured the public imagination and was seen by authors such as Comas i Solà as an activity that could help to elevate the soul. In fact, he saw his popular astronomy programme as part of a peaceful crusade of public good and progress, a particularly useful tool for preaching morality and a social remedy in times of constant political strife. In Comas i Solà’s words, astronomical knowledge helped human beings not only to find their place in the universe and experience intellectual delight, but also to be noble of mind and heart, to annihilate hatred and moral turpitude and to leave the fierce struggles of humanity behind.40

Captivated by the effects that science and technology had on their lives, the citizens of Barcelona visited the Fabra Observatory to listen to Comas i Solà, who intended to help them to better understand such changes. In fact, the Fabra Observatory was to play a crucial role, not only in the political economy of both professional and public science, but also in the shaping of the ideal of a modern city.41

Comas i Solà catered for the general public not only at the Fabra Observatory, but also at his private observatory Vil·la Urània. Indeed, the turn of the century was characterized by the flourishing of both private and institutional observatories. One of the reasons was the establishment of international scientific collaborative networks, leading to decentralization. In the particular case of astronomy, this meant a significant proliferation of observing sites.42

One of these new sites in Barcelona was to be found in the university.43 In spite of the efforts to provide full astronomical training to science students, nineteenth-century Spanish university courses on astronomy were poor.44 Barcelona was the first city in Spain to build an astronomical observatory attached to a university. Earlier attempts in previous centuries had been unsuccessful.45 Some universities had meteorological stations, but astronomical observations were unusual and no specific buildings were set up to permanently house astronomical equipment and make systematic observations. The University of Barcelona Observatory was promoted by Ignacio Tarazona Blanch (1854–1924) and was conceived almost exclusively for the students’ practical instruction.46 The observatory was erected in the gardens of the new building of the University of Barcelona. The building was designed by the architect Elies Rogent in the early 1880s and was one of the first constructions outside the old medieval walls in the new district of Eixample.47 This was an area of transition towards the new part of the city, in which the bourgeoisie gradually built their homes.

The Faculty of Sciences of the University of Barcelona owned not only an outstanding Repsold theodolite, but also a topographic theodolite and a sidereal chronometer, both of them acquired in 1899.48 When Tarazona took up a position at the University of Barcelona, he sought to assemble these instruments. A permanent installation of such instruments was expected to help students to solve problems concerning cosmography and spherical astronomy, particularly those related to the apparent and real movements of stars. Bureaucracy delayed progress and it was not until February 1904 that the construction of the observatory buildings began.49 The observatory’s main instrument was to be an equatorial telescope from the Irish firm owned by Howard Grubb that was delivered to Barcelona in January 1905, soon after the University of Barcelona had completed the observatory.

Astronomy was to find its place in the academic world in Barcelona, in a fluid dialogue with the city. A new set of observational techniques and astronomical instruments as well as disciplining practices and forms of social organization were introduced to the university and taught to students. Nevertheless, access to the observatory was restricted to university and secondary school students.

The establishment of new observational sites in the city was also a result of the rapid increase in the number of amateur astronomers during the second half of the nineteenth century, and therefore the creation of a large and heterogeneous community of amateur scientists. Indeed, amateurs played a crucial role in the development of astronomy during this period.50 Most of them were self-taught, and they conducted some important original research, which was duly recognized by the international scientific community. This was particularly the case for planetary, lunar and solar observations, at a time when government support for astronomical research was still very poor.51 A good example is that of the new generation of young Catalan scientists who pursued their careers during these years on their own initiative, with a very weak institutional support. This had been the case of individuals such as Comas i Solà and Fontserè, the importance of their work having been acknowledged by the 1890s in various French astronomical journals – particularly those under the influence of Flammarion.52

By the end of the nineteenth century, the number of amateur astronomers in Barcelona had grown to such an extent that several authors demanded the foundation of an astronomical society in the city, under the institutional auspices of the RACAB and/or the assistance of individuals such as Comas i Solà.53 However, it was not until 1910 that the Astronomical Society of Barcelona (SAB) was founded.54 This initiative resembled those developed in many other cities, following the foundation in 1887 of the Société Astronomique de France and the creation in 1890 of the British Astronomical Association – organizations that not only promoted cooperation between professional and amateur astronomers, but also encouraged original contributions from amateurs to astronomical research and played a crucial role in the popularization of astronomy.55 After its first year of existence, the SAB had about 400 members and was soon expected to be equipped with an observatory for the use of its members. The new observatory was to house instruments donated by Rafael Patxot, whose observatory at Sant Feliu de Guíxols was to be re-erected in Barcelona.56

Under the auspices of Fontserè and the musician and amateur astronomer Salvador Raurich (1869–1945), the SAB was intended to be a meeting point and the institution in charge of coordinating Spanish, and particularly Catalan, astronomical and meteorological amateurs. However, the foundation of this society exacerbated existing tensions and led to serious conflicts. As pointed out above, the marginalization of Fontserè from the new Fabra Observatory had been controversial, and had an impact in the organization of astronomy in the city. The consequence was a community of local astronomers divided into two groups centred on the figures of Fontserè and Comas i Solà, who had unsuccessfully attempted to control the new astronomical society.57

A few months after the foundation of the SAB, Comas i Solà accused Raurich of campaigning against him and his observations of Mars in the society’s journal. Raurich was a prominent figure in the public sphere through his articles published in such periodicals as Por esos mundos and Nuevo mundo. What was at stake here was not only Comas i Solà’s scientific status and prestige, but also his public reputation as a major scientific authority. As the references were not explicit, however, the Governing Body of the SAB – to which Raurich belonged – asked Comas i Solà to overlook Raurich’s comments.

However, Comas i Solà left the society, which in his opinion had been set up specifically to antagonize him.58 One year later, the Astronomical Society of Spain was founded, promoted and presided by Comas i Solà. An offshoot of the SAB, this new society aimed to encourage cooperation between amateurs and the few local professional astronomers.59 The governing body of this society, later known as the Astronomical Society of Spain and America (SADEYA), was composed of 12 people, 10 of them living in Barcelona.

This situation eventually proved to be dysfunctional. There was not enough activity in astronomy for both societies to survive. The SAB soon made meteorology its main activity, partly encouraged by Fontserè’s own interests and personal relationships with other important Spanish meteorologists. The SADEYA, on the other hand, had a higher level of participation and proved more committed to astronomy. While the SAB was dissolved in the 1920s, after the instauration of the Catalan Meteorological Service, the SADEYA has survived until today.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, both astronomical societies competed and played a vital role in the development of amateur astronomy and the popularization of the discipline in Barcelona. Several initiatives were launched in the city during these years as part of their popularization programmes, providing common ground for the interaction of a small group of experts, a few amateur astronomers and the general public. A good example is the Exhibition of Lunar Studies held at the University of Barcelona in 1912, under the auspices of the SAB.60 The exhibition presented drawings, maps and photographs of the Moon, as well as astronomical instruments and some information about several astronomical societies.61 The exhibition was a considerable success in Barcelona, with an attendance of tens of thousands, including visitors from almost all educational centres and cultural institutions in the city.62

Similarly, in 1915 the SADEYA began the organization of a Fiesta of the Sun, held every June – coinciding with the summer solstice. This festival, originally promoted in Paris by Camille Flammarion in 1904, has been organized every year by the Société Astronomique de France since then.63 Open to the general public, several events were arranged, including astronomical lectures, projection of celestial images, social gatherings and banquets, as well as a guided visit to the Fabra Observatory.64 Both societies organized public lectures in different places in the city on a regular basis, which were addressed to a wide range of audiences – including women.65 One of the high points of these popularization initiatives was the organization of an International Astronomical Exhibition in 1921. It was the SADEYA that organized this event in the Palace of Industry – built for the 1888 Universal Exhibition in the Parc de la Ciutadella. Fully supported by the City Council, thousands of people visited the astronomical exhibition, in what could be interpreted as a rehearsal for the 1929 International Exhibition.66

The development of astronomy in Barcelona also benefitted from the overall development of the city in the second half of the nineteenth century. The press may be identified as one of these factors.67 The last decades of the century brought about the definitive consolidation of Catalan newspapers, particularly in Barcelona.68 Some members of the SADEYA were convinced of the guiding role that the press played in the public sphere, and accordingly they called on it for some support and publicity – particularly from local newspapers – of their popular activities.69 Such agenda soon included new mass media technologies, particularly after the consolidation of commercial radio broadcasting in the 1920s.70

Furthermore, several scientific industries started to flourish in Barcelona in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This led to a whole set of alliances that benefitted the development of astronomy and its public cultivation. Some of these alliances were made explicit in 1921, when tribute was paid to Comas i Solà during the International Astronomical Exhibition.71 Good examples of this are the public endorsements by scientific instrument makers such as Miguel Hidalgo Vega and José Vilaplana Enrich, and by watchmakers such as Emilio T. Besses and José Novelles Rizo.72

The optician Federico Font de la Vall, one of the pioneers in the development of telephony in Barcelona in the late 1870s, was also amongst those who publicly endorsed the tribute to the Catalan astronomer.73 His name represents an example of the synergies between astronomy and the optical and electrical industries developed in Barcelona during the last decades of the nineteenth century. It suffices to mention the businesses of Juan Roca, Manuel Olió Pigem and Laureano Ychasmendi Errasti. The former owned a shop in Barcelona that in 1910 became the first one in the city making astronomical telescopes.74

Before that, Olió Pigem had set up a shop in the city named the Instituto de Óptica Olió, where glasses, microscopes, electrical apparatuses, meteorological instruments and telescopes were sold. When his brother in law, Laureano Ychasmendi, joined the business, it was renamed the Instituto de Óptica Olió e Ychasmendi.75 By the late 1890s, Olió Pigem was one of the most active amateur astronomers of the city. The back room of his shop soon became the place where regular astronomical gatherings were held. In fact, it was there that the idea for the Astronomical Society of Spain was born and put forward.

The 1921 tribute to Comas i Solà may serve as a better understanding and an example of the status that astronomy achieved in Barcelona during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Astronomy had become a public good, as a result of the programme of public action led by the two astronomical societies founded in the city and by individuals such as Comas i Solà. Such a programme was an appropriation of similar programmes of popularization of astronomy that were successfully developed in countries like France and Britain, adapted to and shaped by the specificities of a growing city such as Barcelona.76 In fact, it was presented as a useful tool for instructing citizens and guiding them in morality, particularly in troubling times. Science, and astronomy in particular, was publicized in terms of human and social regeneration, conveying tranquillity and providing the basis for the progress and welfare of modern society.77

It was thus that Barcelona witnessed the blossoming of new urban spaces in which astronomical knowledge and objects circulated widely. The access to and impact of astronomy went beyond social classes and gender. Public lectures brought astronomy to cultural associations and educational institutions, for the delight of those interested in astronomy. Furthermore, new observational sites were set up, both under institutional and private auspices. All this meant the consolidation of an important network of institutional and amateur astronomers in the city, most of whom were involved in popularization tasks.

As pointed out above, Comas i Solà stood out in this context, publishing regular articles in the daily press and lecturing at many associations and institutions. Furthermore, he opened up the Fabra Observatory to the citizens of Barcelona, integrating this site into the network of new civic spaces that not only brought together research, instruction, spectacle, popularization and leisure, but also contributed to the distribution of credibility, authority and expertise. Indeed, men and women from all social classes were welcomed in this building, located on top of a hill that had been integrated into the city and transformed into a symbol of urban modernity.

In summary, astronomy developed in Barcelona during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as a system that was formed not only by astronomers, academic institutions and astronomical associations, but also by new urban spaces and observational sites that were engaged both in research and popularization, the press and new urban industries. This was a scheme that was shaped by the needs of a growing modern and industrial city, and not only proved to be very appealing for the general public, but also led to a very successful development of astronomy, understood in the broad sense.

1The Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation has partially contributed to this research through the projects Matemáticas, ingeniería, patrimonio y sostenibilidad en el mundo moderno y contemporáneo (HAR2013–44643-R) and Física, cultura y política en España (HAR2011–27308). We are very grateful to Oliver Hochadel, Agustí Nieto-Galan, Charlotte Bigg and Maria Rentetzi for their helpful comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this chapter.

2José Comas y Solá, ‘Nuevo planeta’, La Vanguardia, 16 February 1921, 8.

3See: ‘El entierro de D. José Comas y Solá’, La Vanguardia, 4 December 1937, 3; ‘La muerte de Comas y Solá’, La Vanguardia, 5 December 1937, 3; and Alberto Carsí Lacasa et al., José Comas Solá (Barcelona: Oficinas de Propaganda C.N.T.–F.A.I.–JJ.LL. Comité Regional de Cataluña, [1937]).

4In fact, some other discoveries were perhaps more remarkable. Ralph Lorenz analysed the observation of Comas Solà and concluded that, in effect, he was the first astronomer to describe the atmosphere of Titan. Nevertheless, his observation entailed considerable difficulty and, thus, no other astronomer was able to repeat it. In that sense, the attribution of the discovery to Gerard Kuiper in 1944 is reasonable, given that his work could be more easily reproduced. See: Ralph Lorenz, ‘Did Comas Solà discover Titan’s atmosphere?’, Astronomy & Geophysics, 38, 3 (1997): 16–18.

5See: Samuel Alberti, ‘The Status of Museums: Authority, Identity, and Material Culture’, in David N. Livingstone and Charles W. J. Withers (eds), Geographies of Nineteenth-Century Science (Chicago/ London: The University of Chicago Press, 2011), 51–72.

6Rafael Puig y Valls, ‘La astronomía en Barcelona’, La Vanguardia, 22 December 1889, 1–2.

7 Founded in 1764 with the name of the Experimental Physico-Mathematical Conference, and with the aim of developing a course of Experimental Physics, it was soon recognized by the King with a Royal title. In 1770, it adopted a new name: the Royal Academy of Natural Sciences and Arts. In this early period, Astronomy was not its main activity. However, the members of the Academy began to be involved in astronomical observations and theoretical astronomy during the following decades. See: Agustí Nieto-Galan and Antoni Roca-Rosell (eds), La Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona. Història, ciència i societat (Barcelona: Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona – Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 2000); and Antoni Roca-Rosell, Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona. 250 anys d’història (Barcelona: Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona, 2014).

8Carles Puig Pla, ‘L’observació científica i l’enregistrament fotogràfic de l’eclipsi solar del 28 de juliol del 1851: un cas de col·laboració d’institucions barcelonines’, in Carles Puig Pla et al. (eds), III Trobada d’Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica (Barcelona: SCHCT, 1995), 287–302; Carles Puig Pla, ‘Llorenç Presas i Puig 1811–1875. La Matemàtica Aplicada’, in Josep M. Camarasa and Antoni Roca-Rosell (eds), Ciència i Tècnica als Països Catalans (Barcelona: Fundació Catalana per a la Recerca, 1995), 147–80; Francesc Barca Salom, Onofre Jaume Novellas i Alavau (Torelló, 1787–Barcelona 1849). Matemàtiques i astronomia durant la revolució liberal (Barcelona: SCHCT, 2005).

9On public timekeeping and the development of time zones to coordinate schedules of railroad companies, see: Ian R. Bartky, Selling the True Time: Nineteenth-century Timekeeping in America (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2000).

10See, for example: ‘Crónica’, La Vanguardia, 17 November 1883, 1; ‘Real Academia de Ciencias y Artes’, La Vanguardia, 31 March 1901, 4–5; José Comas Solá, ‘Notas Científicas – Un nuevo Observatorio Astronómico’, La Vanguardia, 17 May 1902, 4.

11See, for instance: Pedro Cerezo Galán, El mal del siglo. El conflicto entre Ilustración y Romanticismo en la crisis finisecular del siglo XIX (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 2003). In general terms, regenerationists desired a global public works programme to create the infrastructure needed for a modern economy. See: Sebastian Balfour, El fin del imperio español (1898–1923) (Barcelona: Crítica, 1997); Juan Pablo Fusi, Un siglo de España: La cultura (Madrid: Marcial Pons, 1999). The basis for this programme was education and science. Consequently, several reforms were promoted in the country in the name of progress, based on reformist ideals. See, for example: Alfredo Baratas Díaz, ‘La cultura científica en la Restauración’, in Manuel Suárez Cortina (ed.), La cultura española en la Restauración (Santander: Sociedad Menéndez Pelayo, 1999), 279–95; and José Luis Peset and Elena Hernández-Sandoica, ‘La recepción de la cultura científica en la España del siglo XX: la Universidad’, in Antonio Morales Moya (ed.), Las Claves de la España del siglo XX. La cultura (Madrid: España Nuevo Milenio, 2001), 127–51.

12Rodolfo Gozalo and Víctor Navarro, ‘Josep Joaquim Lànderer i Climent. València, 1841–Tortosa, 1922’, in Camarasa and Roca Rosell (eds), Ciència i Tècnica als Països Catalans, 459–92.

13On the building of the RACAB, see: Joan Puig-Pey Saurí et al., L’edifici de la Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona: Un testimoni viu de 250 anys d’història urbana (Barcelona: Reial Acadèmia de Ciències i Arts de Barcelona, 2014).

14In Spain, a unified official time was declared in 1900, due to begin in 1901. The different time references were established in the following years. See: Pere Planesas, ‘La hora oficial en España y sus cambios’, in Anuario de Observatorio Astronómico de Madrid para el año 2013 (Madrid: Instituto Geográfico Nacional, 2013), 373–402.

15Fontserè wished to become a teacher at the university, but no positions were available. Working for the RACAB, at least, ensured him an income of which to survive. On Fontserè, see: Antoni Roca Rosell, Josep Batlló Ortiz and Joan Arús Dumenjó, Biografia del doctor Eduard Fontserè i Riba (1870–1970) (Barcelona: Associació Catalana de Meteorologia, 2004).

16This came together with the creation in 1893 of Free Chairs in several arts and sciences, including astronomy, subsidized by the Spanish Society for the Protection of Science (Sociedad Española Protectora de la Ciencia).

17David Aubin, ‘The fading star of the Paris Observatory in the nineteenth century: Astronomers urban culture of circulation and observation’, Osiris, 18 (2003): 79–100.

18Rafael Puig y Valls, ‘La determinación de la hora media en Barcelona’, La Vanguardia, 21 November 1891, 4–5. Many factors contributed to this sense of crisis in Spain around 1900 such as epidemics, floods, wars (the loss of the American and Asian colonies), mutinies, civil disorders, and the insecurity of the middle classes due to the emergence of an organized working class. On the significant role that anarchism played in Barcelona, see Chapter 6 in this volume.

19See: ‘Crónica local y regional’, La Dinastía, 18 May 1888, 2; and ‘Las bodas de plata del funicular del Tibidabo’, La Energía Eléctrica, 28 (21), 10 November 1926, 289.

20Dionisio Puig, ‘El Observatorio del Tibidabo’, La Vanguardia, 11 May 1895, 4; ‘Un observatorio más’, La Vanguardia, 10 May 1895, 4.

21Note that these authors even claimed that meteorological observatories should be run by physicians. See: Puig, ‘El Observatorio del Tibidabo’.

22‘Algo más acerca del Observatorio del Tibidabo’, La Vanguardia, 19 May 1895, 1–2. Urban reformers were particularly concerned with improving the sanitary conditions. One of the most relevant figures was Pere García Faria, whose interest in health matters in areas affected by epidemics led him to develop the sanitation project for Barcelona. See: Miguel Ángel Miranda González, ‘Pedro García Faria, ingeniero de Caminos (y arquitecto)’, Scripta Nova. Revista electrónica de geografía y ciencias sociales, 10 (221), 15 September 2006, http://www.ub.es/geocrit/sn/sn-221.htm.

23In fact, the RACAB project was influenced by the news that arrived from America regarding the creation of new observatories, such as the Lick Observatory, built from a bequest by James Lick.

24‘En la Diputación’, La Dinastía, 15 January 1896, 2.

25See, for instance: George Wise, Civic Astronomy: Albany’s Dudley Observatory, 1852–2002 (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 2004), p. 4.

26Sergi Garriga Bosch, El Tibidabo i la concepció metropolitana de Barcelona (Master Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2012).

27Note that the popular classes frequented Paral·lel Avenue and therefore found it more accessible to go to Montjuïc hill.

28See, for instance: Antonio Torrents y Monner, ‘El Tibidabo y la higiene ó el barrio modelo’, La Vanguardia, 1 September 1903, 1–2; and Manuel Albi y Morera ‘El Tibidabo y la higiene’, La Vanguardia, 2 September 1903, 1. On the introduction of innovations for entertainment purposes and how such a project was related to land speculation, the promotion of tourism and hygienist and civilizing ideals through the development of transport networks, see Chapter 5 in this volume.

29‘Ferrocarril Funicular del Tibidabo’, La ilustración artística: periódico semanal de literatura, artes y ciencias, 20 (1033), 14 October 1901, 7.

30For a complete account of the origins of the Fabra Observatory, see: Antoni Roca-Rosell, La Física en la Cataluña finisecular. El joven Fontserè y su época (PhD thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 1990).

31‘Notas bibliográficas – Anuario de la asociación de Arquitectos de Cataluña para 1903’, Revista de la Asociación Artístico-Arqueológica-Barcelonesa, 4 (1903–1905): 122.

32‘El Observatorio Fabra’, La ilustración artística: periódico semanal de literatura, artes y ciencias, 21 (1061), 28 April 1902, 7.

33On the Cartuja Observatory, see: Manuel Espinar, José Antonio Esquivel and José Antonio Peña (eds), Historia del observatorio de Cartuja, 1902–2002. Nuevas investigaciones [CD-ROM] (Granada: Ayuntamiento de Granada, 2002).

34On the Royal Observatory of Madrid, see: Manuel López Arroyo, El Real Observatorio Astronómico de Madrid (1785–1975) (Madrid: Dirección General del Instituto Geográfico Nacional, 2004).

35In Spain, ‘modernism’ referred to the art movement known as ‘Art Nouveau’ in France and ‘Jugendstil’ in Germany.

36The contributions of Domènech Estapà are analysed in Ramon Graus, Modernització tècnica i arquitectura a Catalunya 1903–1929 (PhD Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2012).

37Febrer and Pòlit became professors at the Faculty of Sciences of Barcelona. Serret, who died prematurely in 1934, was probably the first woman to become a professional astronomer in Barcelona.

38See: Aubin, ‘The Fading Star’.

39José Comas Solá, ‘Admiración y agradecimiento’, La Vanguardia, 17 November 1904, 4.

40Ibid.

41See, for instance: ‘El Observatorio en Tibidabo’, La Correspondencia de España: diario universal de noticias, 10 March 1902, 1; and Orión, ‘El Observatorio Astronómico’, La Vanguardia, 4 December 1903, 4.

42The foundation of the International Union for Cooperation in Solar Research in 1904 illustrates the institutionalization of international collaboration in astronomy and astrophysics in a period characterized by the promotion of cooperative scientific research. See, for example: George E. Hale and Charles D. Perrine, ‘International co-operation in solar research’, Astrophysical Journal, 20 (5) (1904): 301–5.

43During the first half of the nineteenth century, Spanish universities had taught Physical Astronomy as part of general physics courses. It was only in 1900 that a new subject, named Astronomy of the Planetary System, was added to the syllabuses. See: Antonio Moreno González, ‘De la física como medio a la física como fin. Un episodio entre la Ilustración y la crisis del 98’, in José M. Sánchez Ron (ed.), Ciencia y sociedad en España (Madrid: El Arquero – CSIC, 1988), 27–70, p. 69.

44Academic scholars repeatedly complained about the lack of facilities for practical training and education in the subject. See: Memoria del Claustro de Profesores de la Facultad de Ciencias de la Universidad de Madrid, 25 de Febrero de 1898 [Archivo General de la Administración, Sección Educación. Caja 8102. Legajo 8874–1]. Cited in: Baratas Díaz, ‘La cultura científica en la Restauración’.

45A good example is the failed attempt in 1790 by the Chancellor of the University of Valencia to equip the institution with an astronomical observatory. See: Víctor Navarro Brotons, ‘El conreu de les ciències’, in Cinc Segles i un dia (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2000), 119–26.

46Ignacio Tarazona received his scientific education at the universities of Valencia and Madrid during the late 1870s. He obtained his doctorate at the Central University of Madrid in 1880. He lectured at the University of Valencia from 1887 to 1898, and was in charge of the Meteorological Station of the university. Five years later, Tarazona moved to the University of Barcelona, where he was appointed Professor of Cosmography and Geophysics. He later added to this Chair that of Spherical Astronomy and Geodesy, before moving back to the University of Valencia.

47See: Pere Hereu, L’arquitectura d’Elies Rogent, Barcelona (Barcelona: Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, 1986); Carmen Isasa (ed.), Elies Rogent i la Universitat de Barcelona (Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya, 1988); and Mireia Freixa, ‘Elies Rogent i la construcció del Paranimf de la Universitat de Barcelona’, Barcelona quaderns d’història, 14 (2008): 63–80.

48Ignacio Tarazona Blanch, La fotografía solar (Valencia: Tipografía Moderna, 1909), p. 60.

49On Tarazona and the processes of building the astronomical observatories of the universities of Barcelona and Valencia, see: Pedro Ruiz-Castell, Astronomy and Astrophysics (1850–1914) (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008), pp. 89–108.

50For an international perspective, see for instance: Allan Chapman, The Victorian Amateur Astronomer: Independent Astronomical Research in Britain 1820–1920 (Chichester: Praxis, 1998); and John Lankford, American Astronomy: Community, Careers, and Power, 1859–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977).

51See: Antoni Roca Rosell and Víctor Navarro Brotons, ‘Reflexions sobre la ciència i la tècnica a la Restauració’, in Georgina Blanes, Lluís Garrigós, Antoni Roca Rosell and Jon Arrizabalaga (eds), Actes de les IV Trobada d’Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica (Alcoi/Barcelona: Societat Catalana d’Història de la Ciència i de la Tècnica, 1997), 181–90.

52See, for instance, references to Lànderer, Comas i Solà, and Fontserè in: Bouquet de la Grye, ‘Les Progrès de l’Astronomie en 1891’, Bulletin de la Société Astronomique de France, 6 (1892): 151–3, 155; ‘Annuaire Astronomique pour 1892’, L’Astronomie, 11 (1892): 2; and Camille Flammarion, ‘Les Progrès de la Société Astronomique de France’, Bulletin de la Société Astronomique de France, 6 (1892): 159–63, here p. 161. See also references to Lànderer and Comas i Solà in: Camille Flammarion, ‘Nouvelles observations sur la planète Mars’, L’Astronomie, 11 (1892): 36–382, here pp. 374 and 377. On Flammarion, see for instance: Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent, ‘Camille Flammarion: prestige de la science populaire’, Romantisme, 19 (65) (1989): 93–104.

53J. Canudas y Bordas, ‘El cielo en la actualidad’, La Vanguardia, 27 March 1897, 1.

54‘Sociedad Astronómica de Barcelona. Actas. Juntas Generales’, Fons personal de Salvador Raurich, Biblioteca de Catalunya, Barcelona, Ms 4688.

55See: Camille Flammarion, ‘La Société Astronomique de France’, Bulletin de la Société Astronomique de France, 15 (1901): 205–217; and British Astronomical Association, ‘The history of the British Astronomical Association. The first fifty years’, British Astronomical Association Memoirs, 42 (1) (1989): 7–10.

56The instruments were a double equatorial (visual and photographic) of 230 mm (9 inches) aperture and several accessories for spectroscopic, photographic, and micrometric work. See: ‘Notes: The Astronomical Society of Barcelona’, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 22 (2) (1911–1912): 111–12. See also: Manuel Castellet (ed.), Rigor científic, catalanitat indefallent: Rafael Patxot i Jubert (1872–1964) (Barcelona: Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 2014).

57This tension among the Catalan astronomical community is briefly addressed in Antoni Roca-Rosell and José M. Sánchez Ron, Esteban Terradas (1883–1950). Ciencia y técnica en la España contemporánea (Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial, 1990), 54–60.

58Antoni Roca-Rosell, ‘Una vida consagrada a la ciencia’, in Antoni Roca-Rosell (ed.), Josep Comas i Solà, astrònom i divulgador (Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona, 2004), 13–42. See also: Pedro Ruiz-Castell, ‘Priority claims and public disputes in astronomy: E. M. Antoniadi, J. Comas i Solà and the search for authority and social prestige in the early twentieth century’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 44 (4) (2011): 509–31.

59See: ‘Notiz’, Astronomische Nachrichten, 188 (1911): 15–6.

60See: Agustí Nieto-Galan, ‘“… Not fundamental in a state of full civilization”: the Sociedad Astronómica de Barcelona (1910–1921) and its Popularization Programme’, Annals of Science, 66 (4) (2009): 497–528.

61Salvador Raurich, ‘Exposición General de Estudios Lunares, mayo–junio 1912’, Boletín de la Sociedad Astronómica de Barcelona, 19 (1912): 532–4.

62See: Salvador Raurich, ‘Correspondence: The Astronomical Society of Barcelona’, Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 22 (5) (1911–1912): 239–40; and Salvador Raurich, ‘Memoria presentada por la “Sociedad Astronómica de Barcelona” al “Congreso de Sociedades Astronómicas” celebrado en el Observatorio Nacional de París en 22–24 de junio de 1914’, Boletín de la Sociedad Astronómica de Barcelona, 43 (1914): 505–9.

63See: ‘General Notes – La Fête du Soleil’, Popular Astronomy, 12 (1904), 500.

64See, for instance: ‘Notas locales’, La Vanguardia, 26 June 1917, 2; Emigdio Fernández, ‘IV Fiesta del Sol en Barcelona’, Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 9 (67) (1919): 53–7; and ‘Informaciones de Barcelona’, La Vanguardia, 9 June 1921, 4.

65See, for instance, the review of the conference held in May 1921 by Comas i Solà at the premises of Acción Femenina: ‘Informaciones de Barcelona’, La Vanguardia, 27 May 1921, 3.

66Emigdio Fernández, ‘Discurso de Inauguración’, Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 11 (1921): 78–9; ‘La Sociedad Astronómica. Homenaje al Sr. Comas y Solá’, La Vanguardia, 23 November 1921, 22; and ‘Discurso de gracias de Don José Comas Solá’, Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 11 (80) (1921): 109–11.

67On the role played by nineteenth-century periodicals as mediators in the circulation of scientific knowledge, see: Geoffrey Cantor et al., Science in the Nineteenth Century Periodical: Reading the Magazine of Nature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

68Josep Francesc Valls, Prensa y burguesía en el XIX español (Barcelona: Anthropos, 1988), p. 197.

69See, for instance: Fernández, ‘IV Fiesta del Sol en Barcelona’, p. 55.

70On the lecture programming of Radio Barcelona and how astronomy found its place here, see Chapter 10 in this volume.

71Antoni Roca-Rosell, ‘L’exposició organitzada per la Societat Astronòmica d’Espanya i Amèrica el 1921. Josep Comas i Solà i el Regeneracionisme Científic’, in Pasqual Bernat (ed.), Astres i meteors. Estudis sobre història de l’astronomia i de la meteorologia (Vic: Patronat d’Estudis Osonencs; Calvià: Edicions Talaiot, 2014), 229–44.

72See: ‘Lista de las adhesiones recibidas por la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, con motivo del homenaje dedicado a don José Comas Solá, reunidas en el álbum que se entregó a dicho señor’, Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 11 (80) (1921): 112–3; and ‘Lista de las adhesiones recibidas por la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, con motivo del homenaje dedicado a don José Comas Solá, reunidas en el álbum que se entregó a dicho señor’, Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 12 (81) (1922): 15–16.

73See: Horacio Capel Sáez, ‘Estado, administración municipal y empresa privada en la organización de las redes telefónicas en las ciudades españolas (1877–1923)’, GeoCrítica, 100 (1994): 5–61, p. 6; and Angel Calvo, Historia de Telefónica, 1924–1975. Primeras décadas: tecnología, economía y política (Madrid: Fundación Telefónica, 2010), p. 31.

74Josep M. Oliver, Historia de la astronomía amateur (Madrid: Sirius, 1997), p. 26.

75Ibid., pp. 152–5.

76The interrelationship between astronomy and the city in the context of a cultural history of science has been analysed in few occasions. See, for example, Mari E. W. Williams, ‘Astronomy in London: 1860–1900’, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 28 (1) (1987): 10–26.

77See, for example: Antonio Vela, ‘Un recuerdo de la exposición astronómica de Barcelona’, Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 11 (80) (1921): 79–80.