1

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LOST SCHOOL

MUBYŌSHI RYŪ AT A GLANCE

Mubyōshi Ryū is a samurai warfare school from the Kaga domain from around the time of the fourth lord of Kaga, Maeda Tsunanori (1643–1724), who is sometimes also considered the fifth lord. The school appears to have been established in the mid to late seventeenth century, with some of the earliest scroll transcriptions dated to around the 1670s. The school itself contains a collection of “civilian” samurai skills,1 concentrating more on personal protection than battlefield warfare, including the arts of the shinobi and some esoteric magic. The origins appear to center on a samurai named Hagiwara Jūzō and his colleague Niki Shinjūrō, who as contemporaries appear on nearly all the school scrolls. The name Mubyōshi Ryū (無拍子流), which can also be pronounced as Muhyōshi Ryū, is best translated as “the school with no discernible rhythm” or “the school that has no gap between event and reaction.”

無: without

拍子: rhythm

流: school

The name implies that a student of the school will be a samurai who has no identifiable gaps in their skills and defenses, making their offensive and defensive skills complete and whole. Furthermore, as discussed in the schools original scrolls, the name implies that a student of the school shows no delay between an event and the student’s reaction. According to the school’s introduction within the Yawara Jo scroll, mubyōshi is the lack of distance between the beat of a hand clapping and the echoing sound it produces. This means that the student is without gap in their ability to react in combat and that no discernible shape can be found in their strategy.

Mubyōshi Ryū is considered to be connected to the school named Shinjin Ryū (深甚流), which infers a connection to the famed swordsman Kusabuka Jinshirō. Mubyōshi Ryū continued down the centuries, taught in the Kaga domain throughout Japan’s Edo Period when the Tokugawa clan ruled the land. Student records show that the school was healthy and thriving until the end of the period of peace and lasted beyond the end of the samurai themselves, which came about with the Meiji Restoration in 1868. It was at this time—just before the fall of the samurai—that a man named Kaneko Kichibei (1795–1858) really pushed the school to probably its highest level of popularity. After this point it began to decline. Some of the school’s teachings are now no longer a part of the “living tradition,” a percentage of which have been lost forever while some have been preserved through scrolls that remain in multiple collections. The most recent and still current grandmaster of the school is Uematsu Yoshiyuki, who lives and runs his dōjō in Nonoichi within the Ishikawa Prefecture—previously the Kaga domain. Mubyōshi Ryū lives on through Uematsu’s dedicated efforts, through a traditional dance found in the local area, in various scrolls in library and personal collections, and now within this book. Mubyōshi Ryū, the school that gives a person “no discernible rhythm,” is a thrilling and motivating facet of Japanese culture that deserves its place in Japanese history and world recognition to live on alongside its more famous counterparts.

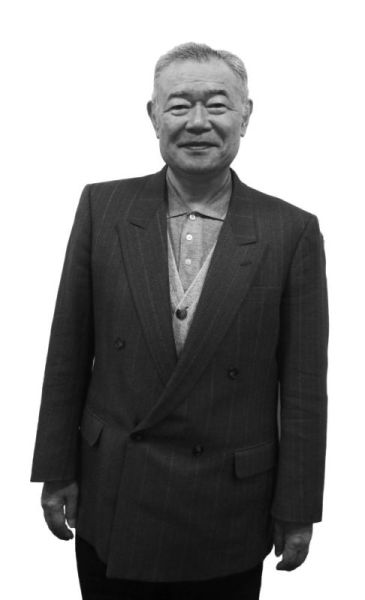

UEMATSU YOSHIYUKI SENSEI

Uematsu Sensei was born in Nagasaki on New Year’s Day, 1948. He began his initiation into Zen Buddhism training at the age of nine under his uncle Mori Gohō in Saga, and received tutelage in the martial arts (mostly Okinawan karate) from Mori. He moved to Ishikawa Prefecture at the age of twenty-four to join the Sōjiji Temple in Monzen. He opened the Mushinkan Dōjō shortly thereafter. He continues his martial arts study with Shinkage Ryū (iaijutsu) and Mubyōshi Ryū (jūjutsu), among others.

Figure 1.1. Uematsu Yoshiyuki, 15th Grandmaster of Mubyōshi Ryū,2 11th Grandmaster of Mukaku Ryū

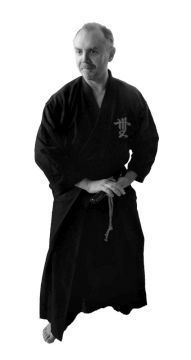

JOE SWIFT

Joe is a native of upstate New York and has lived in Japan since 1994. He has been training in the martial arts since 1985, has been a student of Uematsu Sensei since 1995, and has operated the Tokyo branch of the Mushinkan since 2001. He works as a meteorologist, and in his spare time translates Okinawan karate texts from Japanese to English.

Figure 1.2. Joe Swift

ANTONY CUMMINS

Antony is an author and historical researcher. He concentrates on investigating and disseminating the history of the Japanese shinobi. Taking on the role of project manager and producer, Antony, with the Historical Ninjutsu Research Team, has translated and published multiple shinobi and samurai manuals, including The Book of Ninja, The Book of Samurai, Iga and Koka Ninja Skills, The Secret Traditions of the Shinobi, True Path of the Ninja, and Samurai War Stories. He has also published his own works on the samurai and shinobi, In Search of the Ninja and Samurai and Ninja. Antony has appeared in the TV documentaries Samurai Head Hunters, Ninja Shadow Warriors, Samurai Warrior Queens, The 47 Ronin, and Ninja.

Figure 1.3. Antony Cummins

SUPPORT ARTISTS

Andrija Dreznjak

Andrija Dreznjak was born in 1985 in Serbia and graduated from the University of Niš after studying Law. Andrija’s hobbies include painting, sculpting, and graphic design. He has worked with Antony Cummins on a few projects, including Secrets of the Ninja. He lives in Serbia and works as a freelance sculptor, graphic designer, comic book artist, and script writer for graphic novels.

Figure 1.4. Andrija Dreznjak

James Baker

James Baker is a Cuban American multimedia artist from Indiana. He holds a bachelors in media arts and science from the Indiana University School of Informatics and Computing, where he studied new media. He has also studied various martial arts and has always been fascinated by the ninja. Currently James resides in Indianapolis, where he enjoys making alternative media with a DIY ethic.

Figure 1.5. James Baker

Richard Couck

Richard Couck is a machine builder by trade who lives in metro Detroit and has over fifteen years’ experience in modern machining, welding, and traditional blacksmithing, which has given him the ability to recreate many historical items. He enjoys and is constantly on the lookout for new and unusual tools or weapons to create, not only to see how they worked but to gain full understanding of how they could or could not be used. He creates replica items to fully understand the warriors of history and their tools, and has created the replica tools for this book.

Figure 1.6. Richard Couck

THE DISCOVERY OF THE SCHOOL

Like most good stories, the story of the “rediscovery” of Mubyōshi Ryū has elements of the fairy tale and a series of events that seem almost impossible but which are true. I had previously heard the name Muhyōshi Ryū as a branch of Shinjin Ryū from the Shinobi Hiten catalog and included it in my book In Search of the Ninja, but no more than its name and a possible connection to the shinobi was understood. During the filming of the documentary Ninja Shadow Warriors, Nakashima Atsumi allowed me to photograph small sections of the ninja scroll called Mizukagami. Later, while looking for ninja scrolls, I managed to obtain copies of a scroll called Gokuhiden Shinobi no Sho, which, as always, came in photocopied format and well printed in monotone gray. The text was in difficult sōsho—cursive style—leaving its secrets hidden in the pages with only a slight glimpse given in some characters. Sōsho was the “curse of my life” at that point and needed to be defeated, so to combat this mysterious handwriting style, my team and I contacted a then-defunct group of specialists in Warabi, Saitama Prefecture, in Japan, who had in the past dealt with this type of manuscript. They agreed to reestablish their group and to concentrate on this document. My colleagues Mieko Koizumi and Yoshie Minami joined the group to deepen their understanding also.

Much later, on a snowy winter day, Yoshie and I found ourselves traveling to a semi-famous bookshop a short distance outside Tokyo, trying to find any out-of-print twentieth-century books on the ninja. They had a single copy left, which I purchased. As we discussed my work, the owner of the shop told us that we had timed it just right, and that there was a two-day secondhand book event in Tokyo that was to happen the next weekend, and they had listed a shinobi book that I did not have. So, that weekend, list in hand, Mieko and I made our way to this short event in Tokyo. After some searching and fighting through a mass of old men, we found the book.

Having had quite enough of the jostling and crowded environment, we made our way to the stairs leading up to street level. Below the stairs was a locked glass cabinet filled with old scrolls, documents, and expensive and rare Western books. Looking at the glass, I restrained myself and thought, No, I have been through a million scrolls, and I never find anything of worth to me in these shops. Backing away and waiting for Mieko to retrieve her umbrella and bag from the improvised cloak room, I was accosted by a wizened old man, bent over and overzealous. With his hands on my arm, he led me to the cabinet and started to unlock the glass. I protested as much as I could, knowing that there would be nothing I would want to spend the hundreds if not thousands of dollars that these scrolls could fetch. Mieko came to my side to help me refuse the offer, but by that point I was deep in the scrolls. Unrolling one, I saw the flowers of a flower-arrangement scroll; the next had images of arrows and bows, a typical archery scroll. Mieko began to translate the titles for me: medicine, archery, jūjutsu, and so on, but then I stumbled across a thin but solid roll that looked quite aged.

Figure 1.7. Mieko Koizumi in kimono the day we went to the book festival

Opening the scroll the limited amount that the glass area would allow, the cursive style was set against the beautiful paper with an elegant gold-painted background. It had the title torn off along with the first few sentences, leaving it nameless. Opening it as best we could, Mieko started mumbling as she read and then explained that the sentences, while difficult to understand, were very familiar, with words such as lantern, wind, and rain starting to emerge from the text. Then she said, “Antony, this sentence is from the shinobi scroll we’re using at the sōsho club. This is the exact same sentence that we studied last week, I’m sure of it.” Looking to the scroll and the price, I thought that there had been some mistake. Scrolls cost hundreds if not a thousands of dollars, but this one said three thousand yen (under $30). I thought there was no possible way that this scroll was so cheap. This price should be understood as cheap on a mythological scale, on the verge of being impossible. Scroll in hand, I went to the counter, and sure enough, they took off a tag, charged me three thousand yen, and put the beautiful object in a rather dull plastic bag. Flabbergasted and excited, I walked out to the waiting Mieko—in a splendid yellow kimono—and we walked to the nearest coffee shop for a cup of tea and a better look.

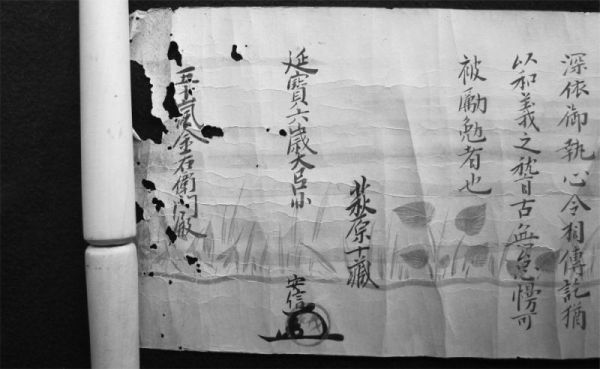

Sitting in the coffee shop, we opened the scroll on the table and made our way through the contents. Bit by bit and with exclamations of glee, we saw the word shinobi and shinobi no mono appear. Could it be that I had really bought a real life ninja scroll for the price of a few cheap meals? Making our way to the end, a seal, names, and a date appeared:

Given to Igarashi Kin’emon by Hagiwara Jūzō in the year 1678

It was evident that I had purchased my first shinobi scroll. The seal appeared to be the original seal of the author, and only one year given. I had stumbled on an unknown ninja scroll by an unknown warrior called Hagiwara Jūzō, and it was an original, actually penned in 1678. Taking my scroll to Yoshie—my main translator—she began to search for Hagiwara Jūzō on the Internet. Only a single result came up. A woman named Mizui Mitsuko was continuing the business of her father who had recently died. He had been an avid collector of military manuals, and now she was selling his collection. In her catalog it stated that she owned a manual titled Mizukagami by Hagiwara Jūzō. Boarding a train to Tokyo, we arrived at her shop in Takadanobaba and settled down to a cup of tea. She produced the manual—this time in book form—and allowed us time to go through it. Yoshie turned to me and said, “This is the same manual as the scroll you just bought,” and with that, my scroll had a name and a place in history. Buying the Mizukagami and two more shinobi-related manuals from her, we set off home. Quickly I opened the photos of Nakashima’s Mizukagami (the scroll that I had taken photos of on the documentary shoot) and we compared his Mizukagami to both of mine. It seemed that our original idea, that only two copies of the Mizukagami existed, was wrong. One was in Nakashima’s collection, and one in an Iga collection, but now there were four. This led me back to the Shinobi Hiten catalog and my original quotation about Muhyōshi Ryū in my book In Search of the Ninja.

Figure 1.8. The end of the shinobi scroll with the signatures

At this point we had the name Hagiwara Jūzō and his School of Muhyōshi Ryū and little else, but it was a start. We found, again recently listed on a website, a scroll called Yawara Jo, for sale in Tokyo, with the name Muhyōshi Ryū attached. Ordering via the telephone, we had it sent to us, and again his name was there, Hagiwara Jūzō. The school and an idea of its history was starting to build. The problem was that the Yawara scroll was a mokuroku, which means that it was a list of skills and not instructions. If only the school still existed, we could turn this useless list into a real book. From here we searched in more detail for the school name and came upon an old and somewhat out-of-date website outlining how the school Muhyōshi Ryū had been passed down and was now in the hands of Uematsu Yoshiyuki. It was not long before I was demanding Mieko get on the phone to him and get me an appointment.

Just before this, I had come across an organization that held and promoted certain martial schools, and in their list I found three scrolls connected to Muhyōshi Ryū: the Mizukagami, The Yawara Jo, and the Kaishaku narabini Seppuku Dōtsuki no Shidai. I asked if I could visit them the next time I was in Japan, being in England at the time, to which I got the very Japanese answer, “It’s a possibility.” Strangely, however, a short time later the very same scrolls went up on Yahoo Auction, and the comments stated something to the effect of “There is a Western man researching Muhyōshi Ryū, and we do not wish for him to purchase or be given these scrolls.” They set the price at around $2,000, which at that time was too much for scrolls that I already had. As it turns out, no one bought this collection of three, and they again went on sale for $1,000, and I bought them through Yoshie. I still don’t know if the seller knows that I ended up being the owner against their wishes.

By contacting the local libraries in Kanazawa to try to find more information on the school, we found many more scrolls, more copies of the Mizukagami, and even to my great astonishment, “new” versions of this ninja scroll with the oral traditions recorded, and even an additional scroll. Without hesitation we ordered copies of most of them. Packing my bags for a trip to Kanazawa to meet Uematsu Sensei and to visit the library, I headed off. The library was more than accommodating, and we photographed all the scrolls we had not ordered, and found our way to the Dōjō of Muhyōshi Ryū.

By coincidence, Joe Swift, a longtime student of Uematsu Sensei, was at the dōjō, managing to only get there once a year while he teaches in Tokyo. The dōjō focuses on karate and iaijutsu sword skills and is where Uematsu keeps the Mubyōshi tradition alive as an undercurrent in the training (it was here that I learned that he called the school Mubyōshi Ryū and not Muhyōshi Ryū). Uematsu Sensei took time to make us welcome and to answer all of my questions, showing us the various publications that we were unaware of and that contained Mubyōshi Ryū information. It was here we first discussed the idea of this book, and later on, Joe Swift kindly offered his help and has become key in the production of this record, the preservation of the skills of Mubyōshi Ryū.

Armed with aid from Uematsu Sensei’s dōjō, a list of original Mubyōshi Ryū documents, scattered and scant publications on the school, and hopefully the divine protection and blessing of the long dead Hagiwara Jūzō, we set out to bring this book into reality. This led us to find many manuals and much information on the school that is not complete but intriguing enough to continue. However, the first step was to decipher the beautiful and elegant grass-style writing found in some of the manuals, and to achieve this we turned to the Warabi Sōsho Group.

Figure 1.9. The author at Kinsei Shiryōkan-Tamagawa Library with a copy of the Mizukagami

WARABI SŌSHO GROUP

Japanese texts can be classified by their writing format in three ways:

Kaisho: block style

Gyōsho: half block, half cursive

Sōsho: cursive

It is a blessed event indeed if a scroll obtained from a library or collection is in block style, as the only difficulty in reading it is unknown vocabulary or context. It is more likely, however, that the text will be in either half cursive or full cursive, which may sound simple but is disastrous for someone not trained in reading it. To combat this and to deal primarily with the Mizukagami scroll, I approached the then-defunct sōsho club based in Warabi, Saitama Prefecture. They agreed to reopen the club to work on this scroll and to help bring the teachings within to light for the publication of this book. Their role should not be undervalued, and thanks must be given to them for their superb effort and achievements.

Club Members

Mieko is also a member of the Historical Ninjutsu Research Team and the main partner on this project. She is without doubt the world’s most knowledgeable person on the history of the school of Mubyōshi Ryū.

Not pictured is Yoshie Minami, also a member of the Historical Ninjutsu Research Team and the main translator for the schools produced by the team.

Figure 1.11. Hatada Tadanori

Figure 1.12. Mieko Koizumi

A HISTORY OF MUBYŌSHI RYŪ

The precise origin of the school is unknown, but a logical and educated attempt can be made to ascertain the story behind how the school came into being. It starts with Shinjin Ryū (深甚流), a sword school said to have been founded on the teachings of Kusabuka Jinshirō. The school had reportedly been passed down in the Kaga domain and arrived in the hands of one Niki Shinjūrō. It is here, in the mid-seventeenth century, where the story of Mubyōshi Ryū starts.

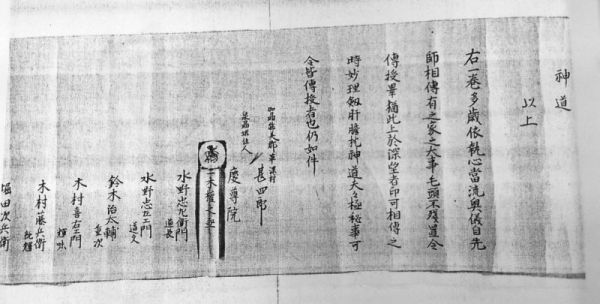

It appears that Niki Shinjūrō was not a wholly pleasant character and that some of his deeds may have been unscrupulous. However, before his name is blackened, we have to establish what is known about him. Under the lord of the Kaga domain, Niki Shinjūrō was a surprisingly and relatively high-ranking samurai with the position of yoriki (group commander). This position gave him control over a body of men who were not paid for by his income but were loaned to him by the lord, and he held captain’s rights over them. It is known that he ran into some trouble or was at least disliked by his school, because in one document (fig. 1.13), his name has a black mark against it. This means that the master, a future master, or a senior in the school disliked his conduct. The mark shows that he was either removed from the school, some internal issue unfolded, or even that his name was scratched off from the list. The facts of this incident have been lost, but what remains is that Niki Shinjūrō is named at the start of most scrolls in Mubyōshi Ryū, and beside his name the samurai named Hagiwara Jūzō can be found.

These two names, Niki Shinjūrō and Hagiwara Jūzō, provided an anchor for the origins of Mubyōshi Ryū and places the establishment of the school at around the mid-seventeenth century. One might automatically place Niki Shinjūrō as the founder of the school because his name appears on most of the documents in the primary position, but the case is not so simple. According to the document Bishamonden (translated in full in chapter 7), Hagiwara Jūzō was a samurai who faced trouble from an early age. Having to deal with old family feuds and repercussions from mistakes in his youth, the young Hagiwara Jūzō sought the teachings of masters of the martial arts and warfare to help defend himself, which indirectly led to the creation of his school, presumably Mubyōshi Ryū.

Figure 1.13. Note the black mark next to the name Niki.

Through investigation it seems more likely that Niki Shinjūrō was a member of Shinjin Ryū and that Hagiwara Jūzō studied that school under him, including other forms, such as grappling and chain weapons. Therefore, it appears that Hagiwara Jūzō was the founder of Mubyōshi Ryū but that he gives Niki Shinjūrō respect through his prime position in the school’s list of masters. This, of course, is to display two major points: first that the skills have a lineage that is authentic, and second that this lineage can be traced back to Kusabuka Jinshirō—a famed samurai and sword master.

It is imperative to understand that Shinjin Ryū is primarily a sword school and that Mubyōshi Ryū has a distinctive lack of swordsmanship. This means that Hagiwara Jūzō did not adopt these sword skills—he simply and most likely became and continued to be a student of Shinjin Ryū—and that Mubyōshi Ryū contained all the other elements, such as grappling, rope skills, and quarterstaff work (it does involve a small amount of swordsmanship). In addition to this, Hagiwara Jūzō also added ninjutsu—the arts of the ninja—to his curriculum. It made the combination of Shinjin Ryū and Mubyōshi Ryū a solid school for an independent warrior, giving that warrior all the skills he would need to survive in postwar medieval Japan.

Mubyōshi Ryū seems to have been started by one man to defend against his enemies and appears to have thrived and continued, a testament to its effectiveness. Upon observing the gathered collection of Mubyōshi Ryū scrolls, a pattern of names begins to appear, showing a core group of strong members around its origin. As discussed above, the name Niki Shinjūrō always appears first, with Hagiwara Jūzō directly after him, and then followed by others that constantly reappear and should be considered the founding members or first set of masters, with Niki Shinjūrō being the link to the past:

Niki Shinjūrō Masanaga

Hagiwara Jūzō Shigetatsu

Tōmi Gen’nai Nobuna

Kitagawa Kin’emon Sadahide

It seems evident that Hagiwara Jūzō is the founder of the school, under the guidance of Niki Shinjūrō, but also that others core members of the school were training with them or directly after them in succession. The school clearly becomes a standard school for the Kaga domain, and students flock to its banner while it resides in the Keibukan (the main samurai training hall of the Kaga domain) with the other official schools of the area.