The Beatles made an enormous splash in Liverpool. But as big as they were, there was one commodity that was much bigger and much more controversial.

Liverpool is a port city. So ships come and go, carrying coal, timber, grains, steel, crude oil, and endless other commodities. Loaded onto ships leaving Liverpool in the eighteenth century was the most controversial product in English history.

In their holds were bars of copper—that ordinary reddish metal that makes a pot or pan look so shiny and bright. Copper looks innocent enough. But it was the currency of the British slave trade.

The ships sailed from Liverpool to West Africa, where copper and brassware were exchanged for slaves who were then carried across the Atlantic to the Americas. There the human cargo was off-loaded, and rum and sugar from slave plantations were carried back to Britain. This triangular trade route from Britain to Africa to the Americas and back was fueled by copper from Liverpool. It was what African slaveholders wanted.

Copper also kept the ships afloat. Sailing around the North Atlantic, wooden ships worked out well. But as slave ships entered the Caribbean, they encountered a tiny mollusk, called Teredo navalis, which feeds on wood. Or, more accurately, these mollusks have a special organ that carries a bacterium that digests cellulose, dissolving the hulls of ships. A few too many mollusks and your ship is on the ocean bottom.

The answer was to sheathe the hulls in copper. Copper kept the mollusks out, the hulls intact, and the slave ships sailing.

Many Britons called for an end to the slave trade. But copper merchants protested vigorously. They were not getting rich selling pots and pans in Lancashire. The slave trade was the market they wanted to protect. Finally, in 1807, public sentiment turned, and it became illegal for British subjects to traffic in slaves. In 1833, slavery was abolished in all British colonies.

Metals always seem to come in the form of double-edged swords. Lead gave us pipes for plumbing, but it has also poisoned countless children. Mercury gave us thermometers and electrical switches, but it also caused birth defects. Metals build bridges and locomotives, and also bullets, prison cells, and hand grenades.

Metals are a double-edged sword within the human brain, too. In the last chapter, we saw that researchers have found plaques and tangles within the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease. If you were to analyze a typical plaque—one of the small deposits that are found among the brain cells—you would discover that much of it consists of beta-amyloid protein. But there is something else there, too. Teasing the plaques apart, researchers have found traces of copper. They have found other metals, too, particularly iron and zinc, and perhaps others, as well.1

All three of these metals are needed by the body—copper for building enzymes, iron for blood cells, and zinc for nerve transmission, among many other functions. You get them in the foods you eat. But it turns out that if you get too much of any of them, they can damage your brain cells. The difference between a safe amount and a toxic amount is surprisingly small. And that is exactly the problem.

Iron and copper are unstable. Just pour a little water into a cast-iron pan and let it sit for a bit. The rust you see is oxidation. Copper oxidizes, too, which is why a bright shiny penny soon darkens, sometimes combining with other elements and turning green.

Pretty colors, yes. What is not so pretty is when these chemical reactions happen inside your body. That’s when iron and copper spark the production of free radicals—highly unstable and destructive oxygen molecules that can damage your brain cells and accelerate the aging process. 2 In a nutshell, iron and copper cause free radicals to form, and those free radicals are like torpedoes attacking your cells.

So, am I saying that memory problems might be caused by ordinary metals like copper, iron, and zinc? To help answer that question, let me take you to Rome, where a research team studied sixty-four women. 3 All were over age fifty but perfectly healthy. The researchers drew blood samples to measure copper in their blood and then gave them a variety of tests to check their memory, reasoning, language comprehension, and ability to concentrate.

Now, overall the women did just fine. None had any major impairment. But some did noticeably better than others on one test or another. And those who had the least mental difficulties turned out to be those with lower levels of copper in their blood. They had adequate copper for the body’s needs but were free of excesses, and that apparently did them a big favor. The difference was especially noticeable on tests that required focused attention.

A study of sixty-four women is not especially large. So let’s next drop in on a research team at the University of California at San Diego that evaluated a much larger group, this one consisting of 1,451 people in Southern California.4 They found much the same thing. People who had lower copper levels in their blood were mentally clearer compared with those with excessive copper. They had fewer problems with short-term and long-term memory. And the same held true for iron. People with less iron in their blood had fewer memory problems.

So even though both iron and copper are essential in tiny amounts, having too much of either one in your bloodstream seems to spell trouble.

If this sounds surprising, it did not entirely surprise the researchers. Every medical student knows that copper is potentially toxic. Your body uses tiny amounts of it in enzymes for various functions, but the amount you need is extremely small. If you get too much of this unstable metal, it can oxidize and encourage free radicals to form. In fact, the only thing that stops copper from destroying your health early in life is that your liver filters much of it out of your blood and eliminates it. In a rare genetic condition called Wilson’s disease, the liver is unable to eliminate copper normally. As copper builds up in the body tissues, it damages the central nervous system and causes all manner of other problems.

Similarly, excess iron has long been known to cause potentially serious health problems. More on iron in a minute. But first, let’s deal with copper and understand what it is doing to our brains.

I should tell you that copper may contribute to much more serious problems than the minor variations in memory and cognition seen in the Rome and San Diego studies. Starting in 1993, a research team from Rush University Medical Center went door-to-door in three Chicago neighborhoods, aiming to track down the causes of health problems that occur as we age. They invited 6,158 people to join the Chicago Health and Aging Project, and eventually another 3,000 joined in, as well.

The researchers carefully recorded what the volunteers ate. Like people everywhere, some were health conscious, while others were not so particular. The research team then kept in touch with everyone over the years to see who stayed well and who did not—who kept their mental clarity and who had memory problems. They then looked to see if any part of the diet could have predicted who might fall prey to memory loss.

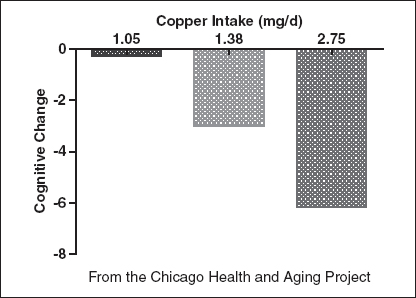

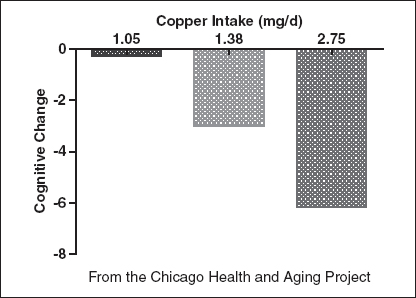

Now, many of the participants got adequate copper in their diets, without excesses. As the years went by, they generally did well on the cognitive tests the researchers gave them. But other participants got quite a bit more of it. Needless to say, none of them were worrying about anything so insignificant as copper. Who would even have known it was in foods, anyway? But as time went on, a particular combination seemed to be especially harmful. Those whose diets included fair amounts of copper along with certain “bad” fats—the fats found in animal products and snack foods—showed a loss of mental function that was the equivalent of an extra nineteen years of aging. 5 It appears that “bad” fats team up with copper to attack the brain. These fats actually assault the brain in many ways, as we’ll see in the next chapter.

The difference in copper intake between those who generally did well and those who did not was surprisingly small. Here are the numbers: For comparison, a penny weighs 2,500 milligrams. The people in the Chicago study who generally avoided cognitive problems got around 1 milligram of copper per day. Those who did not do so well averaged around 3 milligrams per day (2.75 milligrams, to be exact). One milligram, three milligrams—what’s the difference? you might be asking. That is still just a tiny speck of copper. But it turned out to be more than enough to cause serious problems. As we will see shortly, the foods that deliver this innocent-looking, bright, shiny metal are right under our noses, and it damages the brain enough to interfere with attention, learning, and memory—and perhaps even cause Alzheimer’s disease. Or so research seems to show.

Researchers have found a surprising link between copper and the APOE e4 allele—that is, the gene linked to Alzheimer’s risk. As you’ll recall, the proteins made by the APOE e2 and APOE e3 alleles are not associated with increased Alzheimer’s risk. It turns out that these two “safer” genes make proteins that bind copper. They keep it out of harm’s way. The protein produced by APOE e4 does not do that. As far as APOE e4 is concerned, you are on your own. It does nothing to protect you from copper and the shower of free radicals it causes.6

Copper is not the only problem. Iron builds up in the body in a condition called hemochromatosis, causing fatigue, weakness, and pain, and ultimately leading to heart disease, diabetes, liver damage, arthritis, and many other problems.

In the Netherlands, researchers measured iron levels in healthy research volunteers using simple blood tests. Naturally, they varied a bit in their iron levels; some were lower and others were higher. The research team then tested everyone’s memory, reaction speed, and other cognitive abilities. And the results were remarkably similar to the findings with copper. Those who were slowest on cognitive tests were those who had the most iron in their blood.7

Your body packs iron into hemoglobin, the iron-containing protein that gives your red blood cells their color and allows them to carry oxygen. In 2009, a group of researchers checked hemoglobin levels in a large group of older men and women. Those whose hemoglobin levels were in the healthy range did well on cognitive tests. But some people were not in this range. Some were anemic. They had low hemoglobin levels, and they did not perform well on cognitive tests. And other people were in the opposite situation—they had unusually high hemoglobin levels. They did poorly, too. Specifically, they had problems with verbal memory (e.g., recalling words) and perception.8

Following these people for the next three years, those whose hemoglobin levels were in the healthy range tended to retain their mental clarity. Those who were too low or too high in hemoglobin showed more rapid cognitive decline. People with high hemoglobin levels were more than three times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease compared with those who were in the healthy hemoglobin range. 9 The safest hemoglobin level was around 13.7 grams per deciliter. Going very far above or below that level was linked to problems with brain function as the years went by.

Keep in mind that in these studies hemoglobin was a rough indicator of how much iron people had in their bodies. While you need some iron, it is dangerous to get too much.

Zinc is similar in that your body needs a tiny amount. In fact, your brain cells use zinc to communicate with each other. 10,11 But in even modest overdose, zinc can be potentially toxic.

So let’s return to the question at hand. Could it be that memory problems are caused by getting too much of these seemingly ordinary metals—copper, iron, and zinc? While research is still very active, here’s the picture that is emerging:

All three metals—copper, iron, and zinc—are clearly present in the beta-amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease. The first two—copper and iron—appear to spark the production of free radicals that can damage brain cells.2, 12 Zinc’s contribution appears to be different. It seems to encourage beta-amyloid proteins to clump together to form plaques.10,11 Iron and copper appear to promote clumping, too, but zinc seems to be much more aggressive in this regard.1

So it may be that these metals work together, encouraging plaques to form and generating free radicals that attack brain cells. And the problems appear to start early in life, as mild memory problems that pass for everyday forgetfulness, as well as in mild cognitive impairment that for many people is a step toward Alzheimer’s disease.

By now, you are no doubt visualizing toxic metals picking off your brain cells one by one. Well, where are these metals coming from?

Let’s start in your kitchen. What’s under your sink? Copper plumbing has been popular since the 1930s. As copper pipes and brass fittings corrode, copper leaches into drinking water.13

Is there a cast-iron pan on your stove? Iron cookware contributes a significant amount of iron to foods. While that may be beneficial for a young woman with monthly iron losses through menstruation, most other people are more likely to be iron-overloaded than iron-deficient.

Next, take a look in your kitchen cupboard. Do you keep a bottle of multiple vitamins? A One A Day Men’s Health Formula multivitamin has 2 milligrams of copper—more than twice the RDA—in a single pill. It exceeds the RDA for zinc, too. In fact, if you take a look at most any vitamin-mineral supplement, you’ll find copper, zinc, and sometimes iron.

So many of us imagine we are doing a smart thing by taking a daily multiple vitamin, and we are, in many ways. It’s an excellent source of vitamin B12 and vitamin D, both of which are important for health. But the metals that are often added are mostly unnecessary, because you are already getting them in foods. A better choice is a supplement containing vitamins only, without the added copper, zinc, iron, or other minerals. Or you could choose a B-complex tablet, which limits itself to just B vitamins. We will cover vitamins in more detail in chapter 4.

In the 1950s, television commercials pushed Geritol as the answer to “iron-poor tired blood.” The tonic had “twice the iron in a whole pound of calf’s liver.” Doctors promoted iron supplements as an energy booster, too, on the theory that sluggishness was a sign of anemia. Not that they worked very well; fatigue has many causes, and iron deficiency is nowhere near the top of the list.

Take a look at your breakfast cereal. No doubt the food scientists at General Mills imagined you wanted all the iron and zinc they’ve added to a box of Total—a full day’s supply of each in every serving. But you do not need these added metals, and you are better off without them. Many other breakfast cereals are similar, giving you too much of a good thing. I have asked General Mills and the other major cereal manufacturers to limit their supplementation to vitamins and to leave out minerals, which most customers get plenty of already.

So plumbing, cookware, supplement pills, and fortified cereals—these all contribute to an overdose of metals that will do your brain no good. But none of these are the biggest source.

To see the mother lode of metal, stop into any coffee shop in Chicago and order liver and onions. No, don’t eat it. Send it to a laboratory. You would be amazed at what you find.

For comparison, the recommended dietary allowance for copper is 0.9 milligram, as we saw above. A typical serving of liver (about 3½ ounces) has more than 14 milligrams of copper. It also has 7 milligrams of iron and 5 milligrams of zinc, not to mention nearly 400 milligrams of cholesterol.

Now, many people avoid liver because it harbors such an enormous load of cholesterol, among other problems. But they are busily chowing down on beef and other meats. Growing up in North Dakota, I certainly did, and so did my parents and most of the people we knew. Unbeknownst to us, meat-heavy diets are a major source of excess metals.

This is, in fact, a key difference between my North Dakota diet on the one hand, and a plant-based diet on the other. Take iron for starters. Green vegetables and beans contain iron. But it is in a special form called nonheme iron, which the body is able to regulate. That is, nonheme iron is more absorbable if you are low in iron and less absorbable if you already have plenty of iron in your body. That is an amazing feature, if you think about it. The amount of iron in a leaf of spinach or a sprig of broccoli does not change from minute to minute. But how much of it your body absorbs does change depending on how much you need. If you happened to have plenty of iron in your blood already, your body is able to turn down its absorption of the nonheme iron in green vegetables. And if you’re running low, your body pulls more of the vegetable’s iron into your bloodstream.

Meats contain some of this kind of iron. But they also contain a great deal of what is called heme iron. And heme iron is harder for your body to regulate. Even if you have plenty of iron in your body already, heme iron is still very absorbable compared to nonheme iron. It is like an uninvited guest just barging in on your party. It can tip you into iron overload.

Cows get iron from grass and concentrate it in blood cells and muscle tissue. If we eat meat, we ingest the concentrated iron that animals have stored, and it ends up being more than we need. If instead we were to eat plants directly, we would get the iron we need, without much risk of an overdose.

We’re like the big fish in the ocean. A little fish ingests a bit of mercury from pollutants in the water. A bigger fish then eats the little one and gets all the mercury in the smaller fish’s body. In turn, this fish is swallowed by an even bigger one, who now gets all the mercury that has been accumulating up the food chain. And that’s us. We are the big fish in the ocean, so to speak, ingesting whatever the animals we eat have accumulated during their lives.

It is a good idea to step out of the food chain and take advantage of the nutrition that plants bring us directly. In research studies, we have done exactly that. That is, we have asked people to skip meat and other animal products. So breakfast might be blueberry pancakes or old-fashioned oatmeal topped with sliced bananas. Lunch might be lentil soup with crusty bread, a bean burrito with Spanish rice, a veggie burger, or a spinach salad. Dinner could be a vegetable stir-fry, mushroom Stroganoff with steamed broccoli, or angel-hair pasta topped with artichoke hearts, seared oyster mushrooms, and Roma tomatoes. As we add up the amount of iron in the foods they have chosen, it is usually the same or slightly more than when they were eating meat. However, as these foods pass their lips, their digestive tract has the surprising ability to decide how much or how little iron it needs to absorb. If they have a lot of iron on board already, their iron absorption is automatically reduced. If they need iron, their iron absorption is increased. And that is possible because the iron they are getting is nonheme iron. As a rule, it gives you what you need without the excess.

Plant-based diets also help you avoid the overdose of zinc and copper. There are adequate amounts of these minerals in vegetables, beans, and whole grains. In fact, there may be more copper in these foods than in meats. But if you were to do blood tests on people who avoid meat, you would find that they are slightly lower in iron, copper, and zinc, which is a good thing. 14,15 The reasons for this are not entirely clear. Aside from your body’s ability to shut out nonheme iron, there is a natural substance called phytic acid in many plants that tends to limit copper and zinc absorption.14,15

Years ago, all this made nutritionists nervous. After all, we need traces of each of these metals, and many nutrition experts cautioned vegetarians to take extra care to get plenty of iron and zinc. And they reassured meat eaters that they had nothing to worry about.16

Today things have turned around. Nutrition researchers have been struck by the observation that people following plant-based diets tend to keep their iron levels in the healthy range. They are no more likely than meat eaters to dip into anemia, but they are much less likely to accumulate excess iron.14 Vegetarians tend to do fine with copper and zinc, too.

Let me emphasize that it is indeed important to get each of these metals in foods. You need them and do not want to run low. But it is just as important to avoid poisoning yourself with excessive amounts. Getting nutrition from plant sources is the easiest way to stay in the healthy zone.

Growing up in North Dakota, vegetables and beans were not exactly our strong suit. Meat was at the center of our plates 365 days a year. At the time we thought we were doing well. Today we know better.

In the world of Alzheimer’s research, the most hotly debated metal is not any of the ones we’ve discussed so far. It is aluminum.

In the 1970s, researchers analyzed the brains of people who had died of various causes. In people who had not developed Alzheimer’s disease, researchers found very little aluminum. But many of those who had had Alzheimer’s had quite a bit of aluminum in their brains—in one case as much as 107 micrograms of aluminum per gram of brain tissue.17,18 Yes, it’s the same stuff that is in soda cans and aluminum foil, and particles of it were inside their brains.

What was it doing there? Our nutritional requirement for aluminum is exactly zero. It has no role in brain function at all, nor does it play a part in any other aspect of human biology. For many years, public health officials have known that large doses of aluminum are harmful. People exposed to unusually large amounts in the workplace or who have received aluminum in renal dialysis solutions have sometimes developed serious brain damage and have needed a treatment called chelation to remove the metal from their bodies.

As a result of these studies, aluminum became a suspect in the Alzheimer’s epidemic.19,20 Researchers began to debate whether the traces of aluminum we might be exposed to from day to day—in pots and pans or in food additives—could put us at risk.

To this day, the question has not been settled. Some disconcerting evidence came from British researchers who measured aluminum in drinking water. Normally there is almost no aluminum in water as it arrives from wells or streams. But at municipal water purification plants, a process called flocculation introduces aluminum as a way of removing suspended particles. In turn, traces of aluminum stay in the water, and they flow from your tap when you fill your drinking glass.

Looking at the tap water in eighty-eight county districts in the UK, the researchers found that the aluminum content varied greatly. In some it exceeded 0.11 milligram per liter. In others it was less than one-tenth that amount. They then looked at Alzheimer’s cases and found they were 50 percent more frequent in the high-aluminum counties.21

A French study found much the same result.22 In a group of 1,925 people, those with more aluminum in their drinking water had a faster cognitive decline and were more likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Canadian studies added to the accumulating evidence. A high incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in a small part of Newfoundland was hard to explain, except that the local drinking water had particularly high levels of aluminum.23 A study in Quebec linked aluminum in drinking water to a nearly threefold increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. 24 A study in Newcastle, UK, seemed to disprove the hypothesis, finding no strong relationship between aluminum and Alzheimer’s, 25,26 until it became clear that there just was not as much aluminum in the water there compared with areas where the link had been found.27

Since then, researchers have debated whether aluminum is a problem or not.19,28 Many feel the evidence indicting aluminum is not particularly strong. The Alzheimer’s Association calls the aluminum-Alzheimer’s link a “myth” and had this to say on its website:

During the 1960s and 1970s, aluminum emerged as a possible suspect in Alzheimer’s. This suspicion led to concern about exposure to aluminum through everyday sources such as pots and pans, beverage cans, antacids and antiperspirants. Since then, studies have failed to confirm any role for aluminum in causing Alzheimer’s. Experts today focus on other areas of research, and few believe that everyday sources of aluminum pose any threat.29

Many authorities agree with this viewpoint. They feel that small amounts of aluminum do little harm and that your kidneys ought to be able to eliminate the incidental traces you might ingest in drinking water and other day-to-day exposures. Perhaps the aluminum deposits found in Alzheimer’s patients’ brains are just a sign that an already-diseased brain can no longer keep toxins out.

However, others have felt the evidence against aluminum is too strong to ignore,19 and in 2011 a group of Alzheimer’s researchers published the following comment in the International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease:

There is growing evidence for a link between aluminum and Alzheimer’s disease, and between other metals and Alzheimer’s disease. Nevertheless, because the precise mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis remains unknown, this issue is controversial. However, it is widely accepted that aluminum is a recognized neurotoxin, and that it could cause cognitive deficiency and dementia when it enters the brain and may have various adverse effects on the central nervous system.30

So what are we to make of this? Is aluminum a problem or not? I suggest that you not feel a need to take a stand on this unresolved issue. There is no need to bet your brain one way or the other. Instead, it is prudent to simply err on the side of caution. Since you don’t need aluminum, it makes sense to avoid it to the extent you can. You cannot avoid it all, but choosing aluminum-free products lets you steer clear of major exposures.

Aluminum turns up in a surprising range of products. At the University of Kentucky in Lexington, Robert Yokel, PhD, found large amounts of aluminum in many common foods—much more than British, French, or Canadian people were getting in their tap water.

How could that be? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration considers certain aluminum-containing food additives to be GRAS—“generally recognized as safe”—so food manufacturers are free to use them. Aluminum compounds serve as emulsifying agents in cheese, especially on frozen pizza. It is in common baking powders and the products prepared with them. It is in foil and in cookware, and, yes, your spaghetti sauce will pick up a substantial amount of aluminum from an aluminum pot. It is in soda cans, which can leach aluminum into the products they hold.31

Luckily, there are perfectly suitable alternatives for most every aluminum-containing product. Which leads us to how we can protect ourselves from toxic metals.

As I have mentioned, research on toxic metals in Alzheimer’s disease is still very much in progress. But some things are clear: There is never any benefit from overdoing it with copper, iron, or zinc, and there is no need to ingest aluminum at all. Here are sensible steps you can put to work right now to protect yourself:

The discovery that metals are hiding inside beta-amyloid plaques and the revelation that these metals might contribute to everything from everyday mental fuzziness to Alzheimer’s disease were huge breakthroughs in medicine.

While research continues, you’ll want to remember that you do need some copper, iron, and zinc, but all of these metals are toxic in excess. You don’t need aluminum at all. Simple steps will help you avoid potentially risky exposures.

There is much, much more to protecting your memory and cognition. The next chapter deals with one of the most common and decisive issues in brain function—the fats that end up on our plates and in our bodies.