Conclusion

Individual Flourishing

To accomplish great things, we must not only act, but also dream; not only plan, but also believe.

Anatole France

Many Blossoms

As we mentioned at the beginning of this book, one of our key principles is that families’ true assets are the individuals who comprise them. A flourishing family, then, is composed of flourishing individuals.

Our focus throughout this book has been on activities that families can take together to encourage that flourishing, especially amid great financial capital. These practices have ranged from certain types of giving, to self-exploration, to methods of communicating as spouses or grandparents, to practices specific to trusteeship, family meetings, or family philanthropy.

But all this activity presupposes the goal: individual flourishing. Flourishing is a highly personal topic. For example, at a family retreat we led, the group discussed, “What is flourishing?” They came up with a variety of answers, such as the following:

- Thriving

- Growing

- Self-sustaining

- Beautiful

- Harmonious

- Dramatic and alive

- Abundant

- Conscious

- Full of life

- Many blossoms

While flourishing is a somewhat subjective matter, we do not want to end without saying something about what it looks like, at least to us.

The Five Ls

We have found that the simplest way to describe individual flourishing, and one that has resonated with hundreds of families and audiences, is an adaptation that we have made of the account of flourishing offered by Dr. Barrie Greiff in his book Legacy (New York: Random House, 2000). Dr. Greiff is a psychiatrist who has worked with hundreds of patients. From his work, we have derived what we call the Five Ls: learn, labor, love, laugh, and leave (or let go).

- Learn: A fundamental part of individual flourishing is learning. As the Greek poet and politician Solon wrote in advanced old age, “I grow older always learning.” Or as Aristotle wrote in the opening line of his Metaphysics, “All human beings desire to know.” Not everybody loves education—and we have been careful in this book not to urge “family wealth education programs.” Yet everyone loves to learn. This desire is core to being human; its activation is part of our human flourishing.

- Labor: We have already written about the centrality of work to a sense of identity, purpose, and meaning. This labor does not need to be compensated financially. What is crucial is that we feel that it engages our true strengths for the benefit of others.

- Love: Even in a world suffused by commercial relationships, in which everyone supposedly looks out only for himself, love still lies at the center of human happiness and misery. Much of this book has been about how to maintain the humanity of human relationships even amid great financial and legal structures.

- Laugh: Money is supposed to be a serious matter. That appearance is one way it maintains its power. Laughter is a release from the shoulds and woulds of life. When we are tempted to be pompous it reminds us of our foolishness. It is the great equalizer in communities, including families. It is also a balm to pain. It is no wonder that children’s hospitals around the world bring clowns in to bring their patients some joy.

- Leave (or let go): Many spiritual traditions teach that the great source of suffering in human life is attachment, above all the demand that things be (or remain) the way I want them to be (or remain). Letting go of such attachment is the path to relieving suffering and allowing yourself to flourish in the moment, as things are.

As you read this list of the Five Ls, think about yourself. Which of these five do you find it easiest to actualize in your life? Which the hardest? What steps can you take now to begin to live all five? How can others around you, including in your family, help you in this pursuit of individual flourishing? How can you help them?

The Four Cs

The Five Ls can help you picture a sort of portfolio of flourishing: where you are strong and where you are underperforming. They provide a sense of the goal.

To help get to that goal, we use another tool, which we call the Four Cs. We introduced these Four Cs in Chapter 4, in relation to the rising generation’s task of rising, but they apply to anyone at any stage of life.

The Four Cs come from studies of resilience; that is, the ability to bounce from whatever the world throws your way. Resilience is the key factor in determining whether we will succeed or suffer in any given endeavor.

Resilience involves a number of components, including having a good physical and mental state and a strong, supportive social network. But perhaps the most important component in resilience is your mental attitude. The attitude we have in mind here is what psychologists call self-efficacy; simply, the belief that you can “do it”; you can meet whatever life sends your way with grace and integrity.

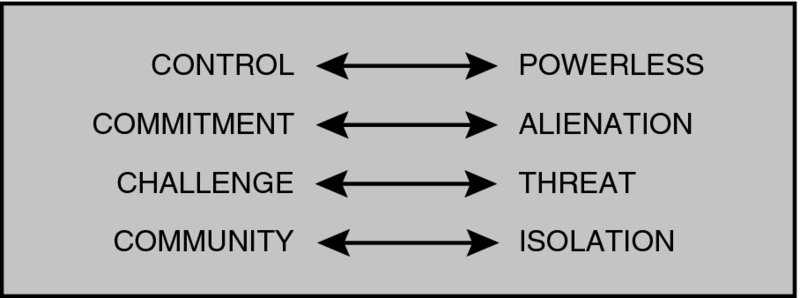

The Four Cs contribute to self-efficacy. They are control, commitment, challenge, and community. They are opposed to powerlessness, alienation, threat, and isolation (see Figure C.1).

C.1 The Four Cs

To use the Four Cs as a tool, think about the space between each C and its opposite as a spectrum. Then think about particularly important situations or circumstances in your life, such as a job or relationship or important choice. Where are you in each spectrum? Are you feeling in control or powerless? Do you feel committed or alienated? Do you feel challenged or threatened? Do you feel that you have a community behind you or are you feeling isolated?

The Four Cs are a powerful tool for flourishing generally. They have special relevance when great financial capital is part of your life. For great financial capital can have the effect of pushing people toward the opposite of each C. If you have made a great fortune, you can feel powerless to keep it—or make sure it does not hurt those you love. If you inherited a great fortune, you may feel disempowered by trusts or other instruments. Great wealth-creators or heirs can feel committed in some ways (such as in philanthropy) but alienated from many other pursuits enjoyed by their peers. Wealth-holders may also feel threatened by others, whom they perceive as targeting them for their riches. Finally, there is no doubt that great financial capital can leave its holders feeling isolated from the rest of society—and even from their spouses and children.

Again, with the Five Ls in mind as a goal, apply the Four Cs to these goals. Do you feel in control, committed, challenged, and in community when it comes to learning, laboring, loving, laughing, and leaving? None of us will feel that we are flourishing in all these ways at the same time. But intentionality can bring us closer, enriching our lives and the lives of those around us.

Three Little Words

We close with three words that, appropriately, came to us as a sort of inspiration when speaking to a roomful of family members. The three of us were on a panel together. The moderator asked us each to share an insight with the crowd. Jay and then Keith took up about 39 of the 40 minutes allocated to all three of us to answer. The host then turned to Susan and asked for her input. In the minute left to her she replied, “As I reflect on what Jay and Keith have shared with you, there are three words I would like to add to their comments. They are humility, empathy, and hope.” We have no doubt that they were the best things that audience took away with them that day. We share them here with you:

- Humility: The journey of complete family wealth is hard. As our opening quotation from Thales suggests, it is easy to tell others what to do. It is very hard to know your own heart and to pursue it bravely. These matters of family and money can be devilishly difficult to untangle with a clear mind and calm breast. Even after studying, practicing, and living these matters for decades, with clients and our own families, we often find ourselves at square one. It is truly a journey requiring a “beginner’s mind.”

- Empathy: We have written about the importance of empathy in family relationships, of the ability to take yourself out of your own head and to put yourself into other’s shoes. Here we would take one step further and stress the importance of empathizing with yourself. So often we are expected to have all the answers, or we expect ourselves always to do the right thing and make the right choices. The journey of family wealth and of life generally is one in which missteps likely outnumber those right choices. Self-compassion is a necessity.

- Hope: One of the constants we have seen in the past two decades since the publication of Family Wealth is the public fascination with stories of wealthy families who have come to grief. However, in recent years we have also noticed more public attention to families who have done well and succeeded over generations, and we have seen more and more families willing to come together to talk about factors in their success. Much of our work is meant to highlight these possibilities. Family wealth need not be a tale of woe. Individuals do grow up happy and healthy. Families do stay together. It can be done.

As the time comes, now, to put back on your regalia and take up your scallop shell, the time to set out on—or continue—your own journey, do so with our thanks for the opportunity to share our gifts with you and with our hopes, as Cavafy wrote, that your journey “be long/full of adventures, full of knowledge.”