CHAPTER 2

COMMIT

I’m not a cliché guy, but the burden of leadership is just that, a burden. You have to make decisions that will affect every man and woman under your command. Lives may be shattered, but you still have to have the balls to make those decisions and stand behind them.

MOTHER

It was Paul Martin’s government that finally gave the green light for the Kandahar mission. Rick Hillier—our Chief of the Defence Staff at the time—warned that this was going to be a really tough mission. There would be casualties. Rick was a forceful communicator and used every rhetorical trick in the book to convince his betters to get on board. He also helped warm Canadians to the idea by talking to the media, famously characterizing the Taliban as “detestable murderers and scumbags” who “detest our freedoms…detest our society…detest our liberties.” With such invocations he helped secure Canadian concurrence that the cause was just and that the pursuit of such a cause might be worth risking and losing Canadian lives.

So under the Martin government, the imminent thrust into Afghanistan was clearly articulated. Then the government changed. In November 2005, a motion of no confidence was passed by the House of Commons, and Stephen Harper’s Conservatives then formed a minority government after a federal election in late January 2006.

The appointment of Gordon O’Connor as Minister of National Defence—a retired brigadier general with over thirty years’ army experience—raised expectations of broad support for the military, at least within the ranks of the Canadian Armed Forces who saw him as one of our own. With Canada’s forces ready to ship out, a second battalion in the wings, and a brigade group trained and ready to take over command of Regional Command South with full responsibility for military operations in Nimroz, Helmand, Kandahar, Zabul, Uruzgan and Daikundi provinces, the minister’s experience gave us a considerable level of comfort. We could see that the Harper government was committed to the NATO coalition and the three-part role Canada was about to play. In time, the phrase defence, development and diplomacy was widely used in Canadian discussions and documents to acknowledge that force alone could not do the job that needed doing.

That job was to be in Kandahar. In some circles, it’s still in vogue to presume that Canada ended up in Kandahar because it took us so long to commit and all the better spots were gone. Not true.

Lieutenant General Michel Gauthier was on hand as the choice was made. Mike was an engineer officer by training and would be the general named to command the Canadian Expeditionary Forces Command (CEFCOM). This was a new command that began during our rotation into Afghanistan. The planning for Afghanistan was done with two groups inside NDHQ; the outgoing Deputy Chief of the Defence Staff (DCDS Group) and the new CEFCOM. CEFCOM then would take over the duties of the DCDS and become the CDS’ national commander for all domestic and international operations. From Afghanistan we reported to CEFCOM on Canadian national matters, much as we reported to OEF and later ISAF on regional matters. Mike was a details guy with an insatiable thirst for information. I had worked with him before and understood that if I could share everything we were reading, writing, recording and watching in theatre with him, he would take the time to digest it all and be better able to support us. He told me how the decision to be in Kandahar was made.

NATO assumed responsibility initially for the Kabul area of ops in summer 2003 and Canada stepped up right away, assuming lead responsibility for Kabul from 2003 to 2004. It was always intended to be just one year. I can’t remember exact numbers but it was a brigade headquarters, an infantry battalion, plus other bits and pieces—probably just shy of 2,000 soldiers. Later in 2003, NATO expanded to Regional Command North, with the Germans taking the lead. Concurrently we signed up for the ISAF leadership role, with Rick Hillier acting as COMISAF [commander of the ISAF] from February to August 2004. He was therefore in a very good position to advise Canada on possible courses of action following our handover to others in Kabul. Next in order was Regional Command West, and nations were approached initially in the summer of 2004. I remember Canada being involved in the conversation in the early fall of 2004, and we actually sent a recce party to western Afghanistan at that time. But we were just wrapping up our major mission in Kabul and needed an operational pause. We weren’t ready to sign up for another major mission. We were tapped out. Coincidentally, the Italians had already signed up for leadership of RC West by the time of our recce, and took the most visible and accessible locations. Our recce party reported back that two or three provincial reconstruction team (PRT) locations were available, yet all of these were in sparsely populated areas where our efforts could only have limited impact, especially given the considerable resupply and logistics challenges in these remote locations. In such a situation, our troops would have been exposed for very little potential effect. NATO pressed us to take one of them, but it made no sense to us. I participated as Chief of Defence Intelligence in a memorable video conference with SACEUR [Supreme Allied Commander Europe], our CDS [Chief of the Defence Staff] Ray Henault and others, where they pushed us very hard. But the Canadian military recommendation was not to sign up for any of the available PRT locations in RC West, even though they may have been “safer” than other areas. We wanted to be somewhere we could make a difference. That logic was accepted at the political level.

MIKE GAUTHIER

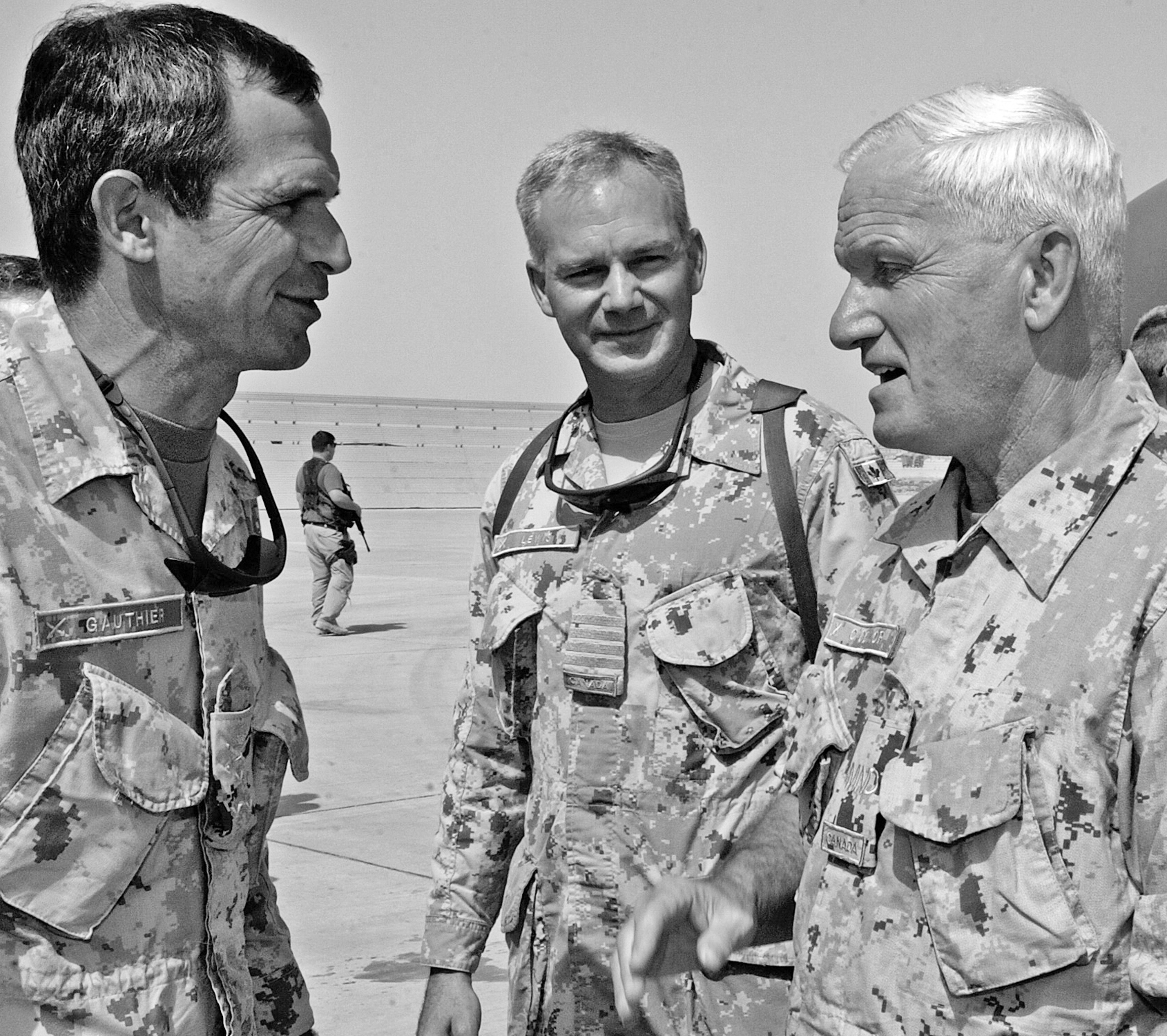

Mike Gauthier, Fred Lewis and Gordon O’Connor.

Lieutenant General Mike Gauthier was my Canadian commander. An engineer, he was Rick Hillier’s operational commander in the Canadian Expeditionary Force Command (CEFCOM) for all Canadian international operations, based in Ottawa. Mike and I talked daily, normally after my day was done and my meetings with either the 10th Mountain Division (under Operation Enduring Freedom) or NATO had concluded. We would recap the day’s events and talk about what was to come next. Mike had a huge capacity for digesting information, but the reports he needed took us too long to prepare, had too many omissions and simply didn’t give him the view from theatre he needed. We changed our reporting procedures and instead I sent him everything that I saw (in the raw), and added my assessment on top of that. While the staff in Ottawa were initially over-whelmed with the volume of information, we all became better able to sense what was going on half a world away from each other. Whenever something bad happened, I would call Mike, which was normally at night when he was asleep. I spoke more often than not to his wife, whom I had just awoken; eventually I advised Mike to move the telephone to his side of the bed. We worked well together. He always supported me in theatre, which was essential, as the relentless tempo of Medusa and our frequent need to adapt to keep the initiative as the Taliban acted meant that our plans had to be fluid. “Fight the enemy guided by a plan” was our motto. The key interlocutor between our in-theatre team and Ottawa was my national deputy, Colonel Fred Lewis. Fred rotated in with 1 RCR and immediately got up to speed. Another engineer, he was always good-natured, thoughtful and a joy to work with. He kept Ottawa informed on the details of what was happening day-to-day, hour-to-hour, minute-to-minute. He was one very busy deputy. The political authority on top of us all was Gordon O’Connor, our Minister of National Defence. A former military officer, he understood our world and what we needed. Some might say he was gruff, but he did more than anyone else to get us the materiel we needed. We’d brief him on the requirements, he’d conduct his due diligence, and then we would find our requirements met. I have never been better supported in any mission as I was by my chain of command—especially from a materiel point of view. Ottawa, in its entirety, pulled together for the troops in the field. Not to say that we always agreed, but the speed at which we were responded to has to be credited in great part to Mike Gauthier and Gord O’Connor. And without a great deputy like Fred Lewis, I would have spent a lot more of my time looking back to Ottawa instead of onto the field of battle, which would have endangered the mission.Credit 5

The UK was also keen to lead RC South, but owing to their major troop commitment in Iraq they could not do so at the time NATO had committed to. Growing insecurity in Iraq in 2004 and 2005 had shaped the expansion timeline in Afghanistan. The U.S. was eager to shift most American troops, equipment and combat air support from Afghanistan to Iraq to bring that conflict to a conclusion. To that end they asked that RC South be fully commanded by NATO by the summer of 2006. And while the authorities in the UK were eager to get out of Iraq, they could do so only at a certain pace; they would not be ready to assume command of RC South until 2007. So Canada stepped up.

In November 2004, we began informal discussions with the British and the Dutch about teaming up in Regional Command South. We had worked with both nations to positive effect over a number of years in one of the regions in Bosnia, and therefore were comfortable with the idea of replicating this partnership of like-minded nations in southern Afghanistan. We understood fully that southern Afghanistan would be substantially more difficult than the west in terms of the strength of the Taliban, although we did not appreciate how much stronger the insurgency would grow from 2005 to 2007 and beyond. As discussions progressed over a period of months, it became clear that the UK could not immediately assume the lead role in RC South in line with the NATO anticipated timeline of summer 2006, and they urged us to take the first command rotation.

In late 2004 we began to look seriously at playing this leadership role and, along with it, basing our forces in Kandahar—which, owing to the already well-established coalition base and airfield there, we judged to be wise. Helmand and the other provinces were too remote for our liking. Canada initially approved assuming responsibility for the Kandahar PRT in early 2005, and several months later approved and announced that we would take on the initial RC South command role with the understanding that leadership would rotate among RC South partner nations. We would also provide a battalion for Kandahar Province (as well as the PRT), which the NATO ISAF request for forces had called for. The decision to go to Kandahar was initially a decision about committing to a PRT (under U.S. Operation Enduring Freedom) beginning in August of 2005. The subsequent and more difficult decision was to commit to the RC South leadership role as well as the battalion in Kandahar, and I believe this was announced by the government in August or September 2005, perhaps a bit later. The former was made with eyes wide open about the potential for the latter. All of these decisions and associated deliberations were made by the Martin government during its two-year tenure.

All of this was done very deliberately, in full consultation with NATO allies and the Americans (who had the pre-NATO coalition lead) over a period of many months and multiple recces. We most certainly were not backed into Kandahar. We believed we could handle it, very much predicated on provision of enablers and support by U.S. forces in place. We also welcomed the opportunity to play the leadership role in this difficult challenge and were confident we were up to it.

MIKE GAUTHIER

Before heading to Afghanistan in early 2006, I had to consider how many Canadians might be killed in theatre. Everyone likes to pretend there is no longer an acceptable body count in a military campaign, but that’s more political imperative than practical habit. For generals, knowing the possible butcher’s bill is essential. Before heading over to take command of RC South, I reviewed the details of every enemy engagement encountered by the Americans who had proceeded us. Combining data about such military metrics as contact type, location and force ratios, I extrapolated from numbers of dead and wounded to arrive at an estimate of what we might experience. I showed it to Rick Hillier and the guys on the Joint Strategic Assessment Committee using a PowerPoint deck to explain the process I had used. Then I unveiled my expected death toll. We would lose between forty and forty-two Canadians between February and November of 2006. Hillier nodded and said, “Great. Now take that slide out and never show it again.” End of discussion. I learned later that he never even raised the figure with General Michel Gauthier, the head of the Canadian Expeditionary Force Command (CEFCOM) to whom I would be reporting from theatre.

I never heard any estimate of likely casualties. Not once. But I can tell you that as they began to tally up during the rotation, I noted the resilience of the political leadership in relation to the mission. There were deaths. Bodies came home. Yet even as repatriation ceremonies escalated, I never had an indication from the CDS or through him from the political realm that anyone had a problem with what we were doing in Afghanistan…until Medusa.

MIKE GAUTHIER

CEFCOM had been created just as we were arriving in theatre. The intent was to improve the way overseas operations are conceived, led and supported. Mike ran CEFCOM, so I’d be talking to Mike a lot. He had three jobs: to oversee the operation, to shape the conduct of the mission over time with guidance from the CDS, and to work closely with the army, navy and air force to make sure our men and women deployed in harm’s way had the tools to do what Canada was asking. In short, his role was to provide clear guidance and orchestrate support for the mission, leaving me and my successors free to execute that mission in response to changing circumstances on the ground.

I’d been focused on Afghanistan since 2002. I’d seen it evolve. I’d been briefed by the U.S. three-star general Dan McNeill in Kabul in June of 2003 (his chief of staff was a peppy guy named Stan McChrystal) who confided in me that the fighting in Afghanistan would all be over by January. Think about that: the corps commander of all U.S. troops in Afghanistan figured it would all be over within months. No criticism, but he was dead wrong because he, like us, could not have known the degree to which things would soon change.

MIKE GAUTHIER

Our mission was never conceived to be a conventional combat operation. We were there to conduct security operations, build the capacity of the Afghan security forces, and carry out reconstruction and development that would directly benefit Afghans themselves. We’d be doing all three of these things concurrently, or at least that’s what we hoped. To channel Donald Rumsfeld, at that time none of us knew what we didn’t know.

We did a recce in August of 2005, ready to undertake the mission as General Hillier had framed it, which was to go and build a nation. Our intent was always to help restore the country to its citizens. Canadians would be there to help Afghans take back control of their lives from usurpers who were intent on destroying their civil rights. So we landed in Kandahar ready to be the biggest—and most robust—provincial reconstruction team ever to hit Afghanistan. That’s how we saw it. We were talking about simply using enough force to push the Taliban out of one village and town after another so that Afghan government forces could re-enter and provide the kind of support and stability that would rob the Taliban of their influence. At that time, counter-insurgency wasn’t even a term we used, and most of us weren’t comfortable later when some of us insisted on using it in our mission statements.

To be clear, Canada was never going into Afghanistan to kill bad guys. Even when things heated up and the Americans were pushing us to chase Taliban all over the place, and capture and kill as many as possible, we never once saw our mission that way. But it’s true that when you sign up to a coalition and multinational operations, you have to allow for some give and take. It’s the only way you’ll be able to achieve all national and coalition objectives, which are often in conflict.

Coalition operations are ugly. The rule of thumb is that if you end up upsetting everyone, you’ve probably hit the sweet spot. In our case, as things would go from difficult yet possible to simply impossible, the pressure would come at us concurrently from national, international, U.S. and NATO interests. I decided early on that only when I had everybody screaming at me from all sides would I know I was doing a good job.