CHAPTER 3

LAND

The Boss told me that in times of conflict, leaders lead, and in between conflict, managers take over. There are senior people out there right now with zero operational experience.

Some of those clowns I wouldn’t follow into a beer store.

MOTHER

When I arrived in Afghanistan in February 2006, I met the theatre commander for Operation Enduring Freedom, Lieutenant General Karl Eikenberry. Karl ran all U.S.-led coalition forces, of which our Canadian Task Force Aegis would now be a part. When I think of him now, two words come to mind: no nonsense. Our brigade appeared in theatre in February when Operation Enduring Freedom was still underway and fully five months before ISAF was scheduled to take over Regional Command South. On day one I and a handful of my senior staff were asked to attend a briefing Karl was to give at his headquarters in Kabul. When we got there, I sat with some thirty other officers at a conference table, but most of the conversation that day was between no one but Karl and me.

Right there in public, he grilled the crap out of me. He began by asking, “Is there anything you bring to this fight that will be in any way useful to me? I could have had any number of brigade headquarters, but I now have yours. Is there some advantage in that?” His interrogation was something right out of Nigel Hamilton’s book Monty: The Making of a General, which details how Field Marshal Viscount Montgomery routinely grilled his commanders to ensure they knew what he needed them to know. Clearly Karl had read that book, because he sure as hell put me through the wringer. He proposed a number of scenarios, demanding to hear how we Canadians would respond should any of them occur. At one point he asked, “What will you do if attacked from out of Pakistan?” I answered that I would return fire for as long as it took to ensure my self-defence. He was more than satisfied with that. Later I let Ottawa in on the rule of engagement I had just conceived on the fly.

Karl Eikenberry was the OEF theatre commander when we arrived. A highly intelligent and energetic officer, he commanded all OEF troops, including 10th Mountain Division and the U.S. special forces. I always went to his office or to briefings prepared for a grilling. When we arrived for our recce in late 2005, he asked us to attend one of his meetings with the Afghan authorities. He held a pre-meeting with his team to go over what the objectives were; and also a post-meeting, which he kicked off by asking, “What did we learn from that?” I liked Eikenberry because he was both smooth and demanding, and he also wanted to teach those around him. I saw that first when we briefed his staff on our incoming formation in Kabul. In a room of about thirty officers, he questioned me for some time on what we could do, couldn’t do, and determined the risk profile of this unknown formation. It was a very challenging meeting that was certainly a good introduction to how things would go. Eikenberry, along with the entire OEF team, was all business. They had been conducting combat operations for years and their members were very experienced. Eikenberry did not hold back on their concerns about the Canadians being merely peacekeepers or the unproven units within the brigade. At the time, it was a very unpleasant session; however, it was absolutely necessary for two reasons. One, OEF needed to understand what they were getting in terms of units and leadership. Two, it was our introduction to how business was to be approached and we realized we would have to pick up our game. Those first months under Eikenberry and 10th Mountain were invaluable to prepare us for Operation Medusa.Credit 6

It appealed to me that General Eikenberry had the capacity to think of everything. I liked that. Each scenario he described was a likely event, so I was eager to offer my response and have it challenged. His interrogation stretched me. We worked through each scene in detail, refined our concept of operations in each case, and brainstormed how we might work under Operation Enduring Freedom and then under ISAF given the alarming spectrum of national caveats restricting our actions.

As Karl Eikenberry and I talked through each situation, we candidly discussed our capabilities and shortfalls. Most of our Canadian soldiers going to Afghanistan would have little other than United Nations experience under their belts. The last time our military saw combat was during the Korean War in the 1950s. It had therefore been ages since we had practised the skills that our American and British counterparts had lately exercised and refined in Iraq and Afghanistan. Our UN peacekeeping and peacemaking missions had taught us invaluable lessons, but not lessons in combat per se. Late in the 90s and in the early part of this century, Canada had begun participating in more robust NATO missions, but those too had not been combat missions. As such our learning curve would be steep for the first few months. We were re-learning how to conduct brigade operations in combat. That’s why we faced such diligent interrogation from our American commanders when we first arrived.

The grilling was the first of many challenges I would encounter as general officer in command in Afghanistan, and I respected Eikenberry for his forthright approach, a deep dive into almost every potential issue. In the end I seemed to have answered all his questions satisfactorily, and he knew what he could get from me and my brigade. When we were done he offered us more assistance in materiel and personnel than we would ever have thought possible.

The second commander I encountered in theatre was Major General Benjamin Freakley. With his 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry), Ben was serving Operation Enduring Freedom as the division-level commander in charge of Combined Joint Task Force 76. I had met Ben twice before and was nervous to do so again, as both earlier encounters had not gone well. The previous summer, while preparing for Afghanistan, I had taken about twenty staff of my brigade headquarters to Fort Drum in upstate New York. We were there for a five-day command post exercise with the U.S. brigades we would soon join in theatre. The idea was that we in command would refine our procedures by working together in simulated combat situations.

Fort Drum was home base for the storied 10th Mountain Division, and had been established in the early 1800s to control smuggling between Canada and the United States on Lake Ontario and the Upper St. Lawrence River. As such, it was associated with a long history of wary suspicion between the two nations, a fact that would soon strike me as poetically appropriate.

Ben Freakley was running this exercise for his own divisional headquarters and was carefully assessing the readiness of the four brigades going with him to Afghanistan. We arrived with a detailed work plan in hand. On the first day I told my staff, “Go meet your cohorts and get to know them. These are the guys we’re going to be working with over there. We’ll regroup at the end of the day and compare notes.” And off we went. I called on General Freakley, who was cordial and welcoming. It was the first time I had met him, and I liked him instantly. He introduced me to his chief of staff, who was also pleasant and upbeat. Knowing how closely we’d be working when I took command of RC South in February 2006, I was encouraged by their openness.

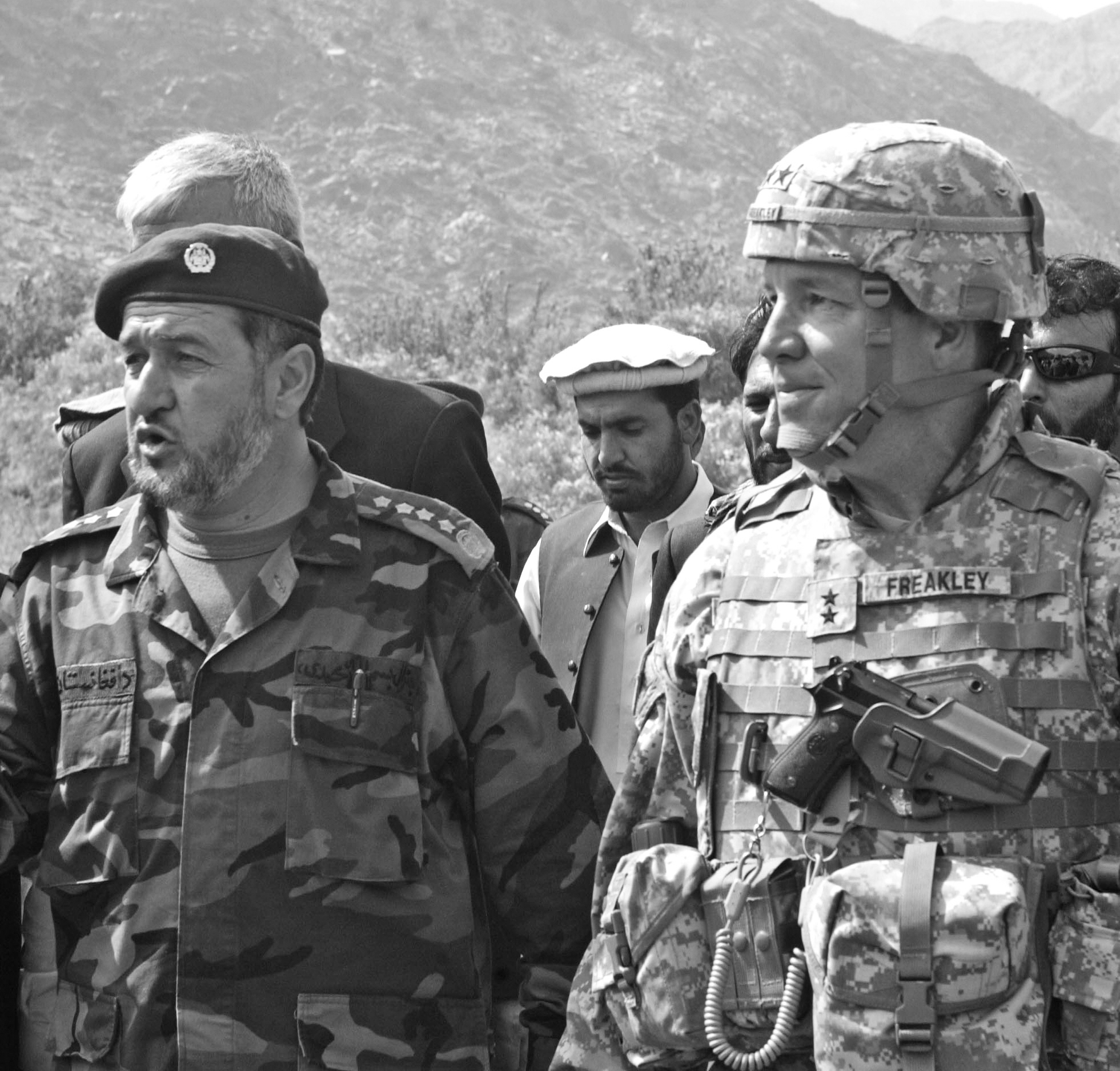

Two warrior generals: General Bismillah Khan Mohammadi, Chief of Staff of the Afghan National Army and Major General Ben Freakley, commander of the 10th Mountain Division and deputy commander of the ISAF. Both were cut from the same cloth because they had grit, never shied away from a fight and loved their troops. Bismillah Khan was in the field during Medusa almost every other day directing his troops. The terrain was not foreign to him because he was a Mujahideen fighter who had fought the Soviets many years earlier. It was good for everyone to see their commander out in the field taking charge of what at that time was Afghanistan’s largest fight. Following Operation Medusa, Bismillah Khan told me that we had done what no other westerners had: fight and win against the defenders on the ground that had seen victories over Alexander the Great, the British and the Soviets. These are words that I will always cherish. Ben Freakley was also out as often as he could. Ben loved the field and talking to soldiers. Whenever he could, he and I would visit Omer Lavoie’s unit and the other elements fighting around Kandahar. We maximized our visits, with Ben talking to the senior commanders and I to the company commanders. We verified what we were being told through various sources, assessed the situation on the ground from our troops in contact, and talked to locals throughout the fight.Credit 7

Not for long, however. As the day rolled on I caught more than one reference to a U.S. brigade combat team out of Louisiana which was also supposedly going to take over RC South. As I knew that role was going to be taken by our Canadian brigade, not theirs, I assumed they had concocted a fictitious scenario for this command post exercise only. I was wrong.

When I first took command of the 10th Mountain Division, I got read into the plan to deploy to Afghanistan for Operation Enduring Freedom. I was under the impression that our combined joint task force would consist of two manoeuvre brigades, an aviation brigade and a sustainment brigade. So four of the brigades I already commanded would be going to Afghanistan. I was unaware of the Canadian-led multinational brigade being considered on the troop list at that time.

BEN FREAKLEY

So they had assumed we were just there for an exercise, no doubt thinking we were later going to play a different role somewhere else. Before the end of the day I went back to Ben’s chief of staff and said, “This may be a stupid question, but you guys do realize we’re coming to Afghanistan with you, right?” He did not. Moreover, he insisted we would not. I replied, “Ah, I think we have a problem here.” By the time our brigade team regrouped, many of us had come to the same realization: “They don’t know we’re coming to Afghanistan.” I phoned Ottawa and explained the situation.

We had no choice. That night we packed up and went home to Canada. All twenty of us.

We had been right, of course. We would be going. The unfortunate confusion at Fort Drum meant only that we did not get the chance to work alongside our U.S. partners before appearing in theatre. I long regretted that.

The next time I saw Ben Freakley was at our own command post exercise in Alberta in the late fall. He came to learn how we operated, and we were equally eager to see how he operated. Ours was to be an international brigade group, meaning that the team commanding Regional Command South would be composed of officers and troops from many different nations. But when Ben arrived many of those international partners hadn’t even shown up yet.

Commanding a brigade is hard. People don’t realize that. When you are a battalion commander, you are expected to have an organization that’s well-framed in the competency it delivers to the battlefield. So if you’re infantry you’re supposed to have a very coherent, well-trained infantry force. If you’re artillery you’re supposed to have a typically qualified, well-trained artillery force. But above those it’s the brigade commander and his staff that become the orchestra conductors who have to know how to blend the capabilities of each of these pieces to a coherent and effective team. It’s like a hockey coach who has to make sure the goalies, the defence and the front line that attacks all play as a team. And serve as a team. You have to train hard to do that well. The brigade training I observed in Alberta was really entry-level, clearly unappreciative of the complexities of regional command style. David didn’t have his full team, that was my first concern. People he was supposed to have in his staff sections weren’t there. And because they hadn’t formed the team yet, there wasn’t trust between the British chief of staff and the Canadians, which would be essential. The team was unformed. I went to my leadership and said, “They are not ready.”

BEN FREAKLEY

Ben Freakley wasn’t our ultimate commander, of course. As I’ve said, until the turnover from U.S. forces to ISAF, Karl Eikenberry was the Operation Enduring Freedom commander we reported to after we arrived in February. After the turnover, David Richards would hold the top job in the coalition. So before and after, I could raise any concerns I had to someone senior if I had to, and sometimes I did. Freakley didn’t think much of coalitions, and yes, he had come to the conclusion that we Canadians weren’t ready for the challenges we had taken on. But once we were in theatre, he always listened and, perhaps because I was a Canadian, allowed me to push back more than any of his own subordinates could when an issue arose. Ben and I didn’t often disagree, but when we did later over matters of operations, there was lots of yelling on both sides.

I had a major argument with Lieutenant General Eikenberry. My view was that we should bring the third brigade, the fourth brigade, the aviation brigade and the sustainment brigade, and conduct operations in such a manner that the member nations of NATO would not have to fight their way into Afghanistan. There was already political friction around the commitment by NATO to come to Afghanistan. And the assumption, the horrible assumption made by NATO leaders and planners in Brussels, was that this was going to be a peacekeeping operation. It was not going to be a peacekeeping operation. In any intelligence that you had, in any open source that you read, in any awareness you had whatsoever, the Americans, the Germans, the Italians and others who were already in Afghanistan were fighting. They weren’t enforcing peace, they weren’t conducting a peacekeeping operation. They were fighting. It was combat. And I was clear with David from the beginning that he was coming to Afghanistan in a combat operation.

BEN FREAKLEY

I had learned before we arrived that our Americans allies harboured a deep concern that we Canadians were about to enter combat on their behalf without being at all combat ready. I couldn’t disagree. Two decades of peacekeeping cannot prepare an army for classic combat.

Peacekeeping, peacekeeping…When you raise a lieutenant to a captain to a major to lieutenant colonel to a whatever, and their training has been only in peacekeeping, and all their practical experience has been only in peacekeeping, and you then thrust them into a combat operation, it’s like asking a cricket player to play football. So you have a mixed group of individuals who are in no way a coherent team. To use another metaphor, you have musicians who all have different sheets of music while the conductor is trying to get them to play one song.

BEN FREAKLEY

Ben Freakley was never shy about voicing an opinion. He was and is larger than life, strong as an ox with a personality to match. He is built like a football player and, like a football player, never took to the field with any thought other than victory. With decades of combat experience, he knew exactly what worked and what didn’t. Part of that came from his significant experience planning for and executing big operations. He helped draft the war plans for Operation Desert Shield in the 1990s, later planned Operation Desert Storm with David Petraeus, then served as Chief of Infantry at Fort Benning, the base on which 120,000 U.S. troops each year are trained and made ready to deploy around the world. As both the head of Combined Joint Task Force 76 and the Deputy Commander Operations for ISAF in 2006, he was in Afghanistan to get hard things done.

We have a number of useful euphemisms in the army. One of them is the word kinetic. When you shoot people and blow things up, you are said to be in the “kinetic phase” of an operation. Freakley was a kinetic guy. He loved a fight and always wanted to be where the action was. For his insistence on rapid and aggressive offensive action, people routinely compared him to General George Patton, who once told his troops, “I don’t want any messages saying ‘I’m holding my position.’ We’re not holding a goddamned thing. We’re advancing constantly and we’re not interested in holding anything except the enemy’s balls…There will be some complaints that we’re pushing our people too hard. I don’t give a damn about such complaints. I believe that an ounce of sweat will save a gallon of blood.”

Freakley was tough on everyone, always in the pursuit of complete readiness for battle. Yet he was fair, honest, respectful of talent, open-minded and ready to learn. He worked hard to give those under him the assets they needed to succeed, a practice we would benefit from during Operation Medusa when he assigned us his own troops and air support to offset the unrealistic force ratios we faced going into battle.

Tension would arise from one other factor though. I suspect that Ben Freakley did not fully understand the complexity of our international activities in RC South and our whole-of-government approach. We had been sent there to stabilize a situation, aid a populace, help restore a society and give the governance of a democratic country back to its people. The last thing Rick Hillier had said to me before I headed to Afghanistan was, “Dave, build me a nation.” When we wrote our operational plans, we defined our actions with verbs such as secure, defend, and only sometimes defeat. Freakley routinely went straight to the word destroy.

We weren’t conducting warfare as he knew it, or even as he saw it happening in the less complex RC East, where his brigade commander John Nicholson was having a much easier time of it than we were. When Freakley advocated for immediate kinetic action, I countered by outlining the many competing priorities we faced. These included getting civilians to safety, using restraint to minimize collateral damage to people and structures, forwarding development activities as a way of securing the trust of the locals rather than just blowing up their villages to get at the Taliban, and dealing with all the restrictions that each of the various NATO nations had regarding how their troops could and could not be engaged. That kind of nuance just left Ben scratching his head.

In May he sent a team under Brigadier General James Terry from his division tactical headquarters at Bagram Airfield near Kabul to Kandahar. He wanted his own people to look in on our situation and give him the truth. Terry subsequently reported back that we actually knew what we were doing and that the situation was indeed as difficult as reported, if not more so. That’s when Ben Freakley concluded that he needed to assist more than insist.

Rick Hillier was our Chief of Defence Staff and someone I had known for a while. A charismatic and visionary leader, he had an infectious aura—everyone liked him, as did I. He displayed tremendous trust in his people and allowed us to get on with it. This support, coupled with his good humour, made our job in Afghanistan that much more manageable. Hillier came over many times to visit the troops. What people saw in the photos in the papers were lots of laughs, but behind the scenes in one-on-one meetings we had serious discussions about everything to do with mission accomplishment, procurement timelines for essential equipment, etc. Hillier listened intently and ensured that we always had the support we asked for. At the end of his trip in March, he pulled me aside and said that he was staying on for a day and would attend the visit by Prime Minister Stephen Harper. This was a surprise to all of us. Rick was supposed to go on holiday with his wife and friends, but due to this visit he would not be able to. In typical Hillier fashion, he made a joke that his wife would understand but that it would cost him another trip somewhere down the road. Hillier was always able to lighten the mood. Following the transfer of authority to me as the commander of RC South, he looked at me and said, “You’re on your own. Cheers!”Credit 8

Despite our differences, I learned more about being a general from Ben Freakley than from anyone else in my career. He is a man of deep convictions: religious, ethical and patriotic. Nothing he did was based on mere personal bias. No one before or since has displayed such tactical depth and such a strong desire to pass that knowledge on to others. Doctrinally driven and meticulous, he was the only commander over there ready and qualified to discuss the most minute details of plans at length. Given his endless appetite for the specific, it was no surprise to me that Freakley came right to Kandahar when it came time to put the plans for Operation Medusa through a rehearsal of concept drill. He wanted to be part of it.