CHAPTER 4

CONNECT

We had a big learning curve with the terminology. Suddenly we had to use American terms. For example, they say VSA, we say KIA. But whether it’s “Vital Signs Absent “or “Killed in Action,” you’ve still got the same problem.

MOTHER

As co-director of the Bi-National Planning Group in Colorado Springs from 2003 to 2005, I learned a ton about inter-agency cooperation. While its name was nondescript (read “boring”), the organization was responsible for coordinating joint foreign policy, defence and security approaches between the U.S. and Canada after the 9/11 attacks. Big stuff.

Back in 2002, it was obvious that an overarching vision for continental defence and security organizations was completely missing from the North American dialogue. The U.S. was reacting quickly and resolutely on its own—among other things, creating the United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). As a combatant command responsible for homeland security and defence, it was the first of its kind since the formation of the Continental Army in the time of George Washington. Canada decided not to get formally involved as we had with NORAD (the North American Aerospace Defense Command), but joint issues such as maritime domain awareness, support of civil authority, and intelligence sharing had to be coordinated, so the Bi-National Planning Group was born. Working alongside USNORTHCOM, we did everything NORAD didn’t.

In my role as director, I worked with Americans on two questions: how to share critical intelligence in a post-9/11 world, and how to use our militaries to support civil authorities tasked with keeping citizens safe. One of our big successes was to change the habit of passing intelligence between Americans and Canadians from a need-to-know to a need-to-share basis. We knew that in a world of web-connected global terrorism, there would never again be time to figure out who needs to know something before that something explodes. The people you trust should get to see everything you have. With more qualified experts looking at more granular data, the likelihood of sniffing out and stopping terrorist plans would be greater. Since then, history has proved the wisdom of that approach many times over.

From the Americans I learned volumes about the dangers of thinking that any military can go it alone in hostile situations. Armed forces have centuries of experience standing up to other armed forces, but in the world of thugs, drug dealers, warlords, insurgents, arms merchants, bent politicians, corrupt businesses, bogus advocacy groups and fanatical anarchists such as Al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, Hezbollah, Lashkar-e-Taiba, Al-Shabaab, Hamas, Farc (I’m stopping for breath here), the Lord’s Resistance Army, ISIS and the Taliban, a conventional military on its own has limited value. Most of today’s battles are gang wars, so you better put people on your team who know how to fight them.

I had eye-opening conversations with senior officers in the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the agency started by Richard Nixon in the early 1970s to stop the flow of drugs from places like Colombia. You don’t have to watch Narcos on Netflix to know how that went. Despite an almost unlimited budget, no agency was able to stem the tide of illicit drugs onto the U.S. mainland, but there was an upside. The DEA learned a lot about the mistakes it made and is eager to share them with anyone going into a situation where drug money fuels a local or regional economy. Think Afghanistan and heroin.

The guiding principle in these situations is to connect with the community that has the problem. You can’t start by shooting and arresting people. You must make human links based on respect and trust, and prove to the people you’re trying to help that you can be of greater value to them than the thugs controlling them. Think thugs like the Taliban.

But who knows how to do this? Not the military. Not the diplomats. Not the NGOs. It’s the police. Cops think differently than soldiers. They work a beat. They show up over and over. They get to know people. They help people. In time, people learn to trust them and they tell them things.

Human intelligence is an invaluable commodity. Coming out of my time in Colorado, that thought was top of my mind. So when I began planning for our rotation in Afghanistan, I knew we needed cops on the team. A talented police officer can tap into local knowledge and gather personal opinions about what is going on. So I began telling people that I was looking for police officers with community experience to be a part of my intelligence group. They could help collect information and analyze what it meant. We would then know what the local people knew, what they needed, what they were afraid of, and what they thought we should do first to contribute to their security.

I didn’t have to look long. While we were still in Canada, someone said, “Oh, we have a policeman joining the team up in Kabul. His name is Harjit Sajjan. He works in Vancouver as both an army reservist and a policeman. And he does gangs.”

Bingo.

I said, “Outstanding. But he’s no longer going to Kabul; he’s coming with me to Kandahar. I need a policeman, because the Taliban are nothing more than a bunch of thugs. He’s the kind of guy I want.” We met in Edmonton soon after.

Harjit was born in the Punjab, arriving in Canada when his parents came to seek a better life. In his teenage years he rode with a rough crowd, but found the courage to ditch some friends who were encouraging him to join a street gang. That decision shaped him. After that, he took pains to find ways to contribute to the community, later joining the militia with the British Columbia Regiment, the police with the Vancouver Police Department’s gang squad, and federal parliament in 2015 as the MP for Vancouver South. That same year he would be named as Canada’s Minister of National Defence.

But in 2006 he was just a cop on a leave of absence from his department, serving his country as a soldier in Afghanistan. I admired him. We spoke about what I needed from him, and when he asked how things were going to work, I said, “We’ll figure it out as we go along. But I need you to be working with my intelligence guys. You’re a policeman. I need your police mentality to help my military intelligence guys understand the Taliban. They’re not a formed army; they’re thugs, a bunch of pick-up guys running an operation no different than the gangs you deal with in Vancouver.” He agreed to join the team.

In March 2006 we had an important meeting with the Governor of Kandahar at the Tea House at Kandahar Airfield. I took Harjit Sajjan with me. Harj did not look like your average Canadian grunt, and the governor took an instant liking to him. While Afghans share a long border with Pakistan, that’s relatively recent. Their hearts still lie with their historic neighbours in India. They are particularly fond of Sikhs, with whom they identify. Sikhs and Afghans are revered worldwide for their deep courage and notable success repelling invaders. They are both warriors at heart.

The governor’s nod proved that Harj had broken down the first barrier. I made him our liaison with the governor’s office from then on. But his greater task lay ahead. “You’re a policeman,” I said. “Go do community policing. There’s your community—it’s called Kandahar. Get to know the tribal elders and the people they trust. Get me information on what’s going on from the Afghan point of view. Speak with my voice when you’re out and report directly to me when you return.”

Harj dug in. He started talking with everyone, and he was good at it. He got a whole bunch of information and reported it in substantial detail. The stuff he gathered was primary-source, from Afghans themselves. We compared that evidence with our other data sources. If all those sources said the same thing, then the raw data became actionable intelligence. That’s how, over time, we built situational awareness. Based on that awareness, we came up with plans to deliver the effects I was trying to achieve. Harj had helped us connect with the locals.

Another great source of local information was our padre, Captain Suleyman Demiray. Suleyman was born and educated in Turkey, graduating with his Master’s in Theology from Ankara University. He emigrated to Canada in 1993. Ten years later, he became the first-ever Muslim chaplain in the Canadian Armed Forces. When he headed with us to Afghanistan, he had intended to do the usual and simply serve our troops as a padre. But it occurred to me right away that Suleyman was the only guy in our entire brigade who could legitimately enter a mosque. Therefore I gave him specific orders: “Engage the Muslim leadership. Talk to the religious leaders, professors and elders and start building relationships with them. Show them we’re here to listen and help. That’s exactly why we’re all here. I can make that point in local political circles, but I can’t in religious circles. You can.”

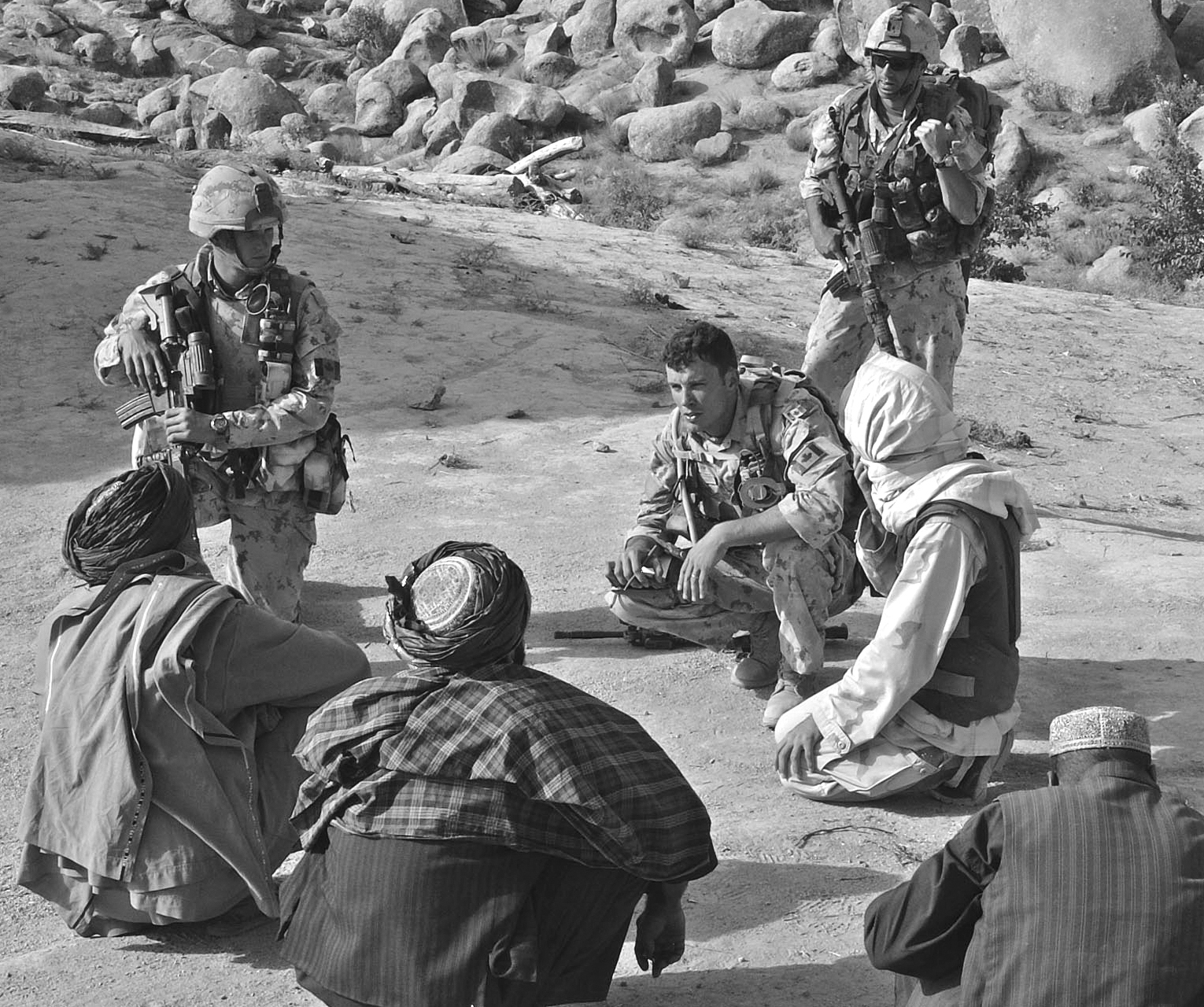

Everyone thinks mostly about the kinetic operations we conducted, whereas the majority of the time soldiers were interacting with the locals to establish relationships and deliver the things they wanted and needed. It took time to build these relationships because Afghans have seen so many foreigners and are justifiably distrusting. An understanding could only materialize after months of working with them, listening to them and most of all delivering real things (not just words). We never met with local villagers without doing our homework first and figuring out what they needed.Credit 9

Like Harj had done, Suleyman jumped in with both feet. He started going into mosques and talking to people, and he accompanied us to meetings of every kind. I remember the day we opened up Forward Operating Base Martello, a Canadian outpost in the northern part of Kandahar. Padre Demiray was right there with us, and everyone in attendance was stunned. Really perplexed. Who was this guy? They knew the uniform, but inside it was a man who looked a lot more like them than any of our soldiers. And then he started to pray with them, in their faith, in their language. Amazing.

Once he did that, we had them. They rallied around and asked him where he was from. “Canada,” he said. “I’m Canadian. I’m a proud Canadian. I’m a Muslim Canadian. And I’m in the Canadian Armed Forces. I want you to know that we’re here to help you, we’re here to work for you. Now what can we do?” And then he listened, over and over, until he learned things we never could have discovered without him there.

In early June in Kandahar, Suleyman met with Mawlana Abdul Samed, assistant director for Hajj and Awqaf, which means “Pilgrims and Trusts.” Basically, he was the regional deputy of religious affairs—slated soon to become the director. Suleyman asked Samed what issues his team were struggling to overcome in the area. Samed offered some eye-opening insights. He reported that in the city of Kandahar there are two hundred mosques with the authority to offer Khutbah, the regular ceremony in the Islamic tradition of prayers and preaching that typically falls on a Friday. At that time, only fifty of the imams who offered the Khutbah in those mosques were paid by the government, and the government was months late in paying them. So virtually every mosque in our region had to turn to its own congregation to fund the operation and maintenance of the facility and provide the meagre income of its imam. Few congregations could afford to pay. They needed a benefactor and one had stepped right up. The Taliban.

Christina Green worked for the Canadian International Development Agency in Kabul. I heard about her from people in the development world and she was the professional we needed to build our sector development plan. It took tremendous effort to lure her away from Kabul and work for us in the dusty and under-developed south. Add to that fact, the necessity to work with soldiers who do not have the best of reputations for ‘building’ and she was very wary of our invite. After some time, she came onboard and I cannot say enough about what she did. She never gave us, the military, any quarter for what we did. She was like a fresh set of eyes questioning us and ensuring that we always had a development component to everything we did. Christina was good humoured and driven to help Afghans which added to our own credibility. She was connected with the development world and found resources we would have never found, and she produced plans and coordinated our efforts in the south that became a force multiplier of note. She was one of a kind as far as we were concerned.Credit 10

The Taliban were now routinely funding most of the mosques in Kandahar and the districts surrounding the city. Their money came with only one condition: the Taliban got to write the words spoken each week by the imams. In the campaign for hearts and minds, while we were dropping leaflets out of airplanes, the Taliban were preaching weekly to the faithful who were at the mosques to learn what was going on, what it meant, and how they as devout Muslims should respond. We weren’t even allowed through the door. No wonder we were making so little headway.

Suleyman wrote a detailed report on the situation, and it rippled right up the chain of command. No one had suspected that the Taliban were entrenched at that level. The Americans had been in this country for over four years and never suspected. Thanks to our padre, we were able to make some sweeping recommendations, including that the salaries of all religious teachers and imams be paid directly by the Minister of Hajj and Religious Affairs, that training centres be established to re-educate local religious figures in the legitimate articles of the Islamic faith rather than the Taliban propaganda in which they’d been steeped, that religious inspectors and intelligence officers move out into the rural communities to rediscover what the true needs were, and that imams and mullahs who served their communities without Taliban influence be paid bonuses. The proposals were accepted. As Rick Hillier had hoped, we were beginning to help the Afghans rebuild their nation.

Once these recommendations had been made I told the padre that I had good news and bad news: “The good news is your work is having a deep positive effect. The bad news is you’re not finishing your tour. You’re staying here with me.” Looking back, I could have used a hundred guys like him. He was a model Canadian—conciliatory, inclusive, attentive, caring. He didn’t send messages to people; he related to them. He participated in an honest exchange of ideas. Nothing less was required, because Afghanistan is a nation of countless cultures and factions, a male-dominated society shaped by fifteen centuries of war.

The Afghans have an unbelievable traditional and historic culture. They have thrown off their oppressors many times—with British occupations in the 1800s, the Russians in the 1980s. They are very fiercely independent people, even tribe by tribe, and those tribes are not for the most part cooperative with one another. There are great rifts over who’s got power and who’s got control. There is a great east–west oblong area heavily occupied by the Pashtuns that extends across Kandahar, Uruzgan, Helmand, and well into Pakistan, which people sometimes call Pashtunistan. You have the Hazaras, mostly out of Bamyan Province, who are looked upon as sort of the lowest caste of this society. They seem to be pragmatic, hardworking people. You have the Tajiks out of Panjshir Province who are fierce fighters and had the relationship with Ahmad Shah Massoud, who ran the Northern Alliance and fought the Russians and the Taliban and was killed by Al-Qaeda. The Tajiks draw their strength from a tight-knit community in the Panjshir Valley, which, because of its high mountains and limited passes, is a sanctuary for the Tajiks. Very hard to get into, so there hasn’t been a lot of fighting there. You can then add in the Uzbeks. All these tribes are like small nation states. They cooperate when to do so is in their best interests, and they don’t when they can’t see an advantage. Their culture is hard to understand. Even if we were there for a hundred years, we probably wouldn’t get the culture right trying to figure out all the tribal and elder hierarchies, and who sways the people.

BEN FREAKLEY

The tribal dynamics alone were more complex than anything I’d seen in my twenty-five years in the military. Seeing those affiliations at work, we began to appreciate that there was much more going on than either our reports or our maps could convey. I asked to see an additional tribal map, and immediately we began to sense how the locations of particular tribes could help us predict patterns of social behaviour. This growing understanding of the human geography of the region significantly enhanced our assessment of what was and was not happening. We could have just gone out and killed people, but that wasn’t anywhere near our mission. For one thing, for every guy you kill you create ten new insurgents, so military force alone would have been useless. We needed to understand people, side with them, train them, and help them build the capacity to sustain a better life.

Our soldiers knew that instinctively. The idea of helping locals develop vocations by which they could profit was motivating, and many of our men and women made a habit of using their downtime to teach Afghans marketable skills such as carpentry, metalwork, and electrical installation and maintenance. They would pitch in on building projects with families in Kandahar, bringing boxes full of tools and leaving a few of those tools behind as gifts. In a way, this activity was provincial reconstruction at its best—and reconstruction, after all, was a priority for us.

Sometimes, the contributions made by individual Canadian soldiers had deep and lasting impact on the whole country. I learned only recently, for example, that Major Rick Goodyear, a National Command Element comptroller who joined us midway in our tour, arrived at the idea that a change in the way banking was done could help the Afghan economy in important ways.

In August 2006, I deployed to Kandahar, Afghanistan as the Task Force Comptroller. When I arrived NATO nations were making 85 per cent of all their vendor and contractor payments in American dollars. In my experience, a currency is part of a country’s fabric, something that citizens associate with their national identity. The American dollar was the currency of choice and its prevalence was undermining the credibility of the native currency, the Afghani.

One of the common problems with any developing nation is that it takes a long time, sometimes decades, to establish the credibility of their currency, especially after a major conflict. Within a month of arriving in theatre I drafted a policy that all Canadian Forces personnel engaging in contracting and procurement in Afghanistan would make their payments in Afghani whenever possible.

The next objective was to get other nations to adopt the policy as well. I chaired a regular meeting of all the major contributing nations’ finance officers. I outlined the rationale behind making payments in Afghani and convinced all the troop-contributing nations to adopt the same policy. There was an initial concern about whether or not there would be enough Afghani to use, but the truth is that no one had ever checked or asked. It was not an issue. The Afghans were quite willing and capable to provide the cash we needed.

Previous to this initiative, the majority of troop-contributing nations were also importing U.S. dollars from outside the country to pay contractors. This left the Afghan government with little to no ability to monitor the inflow and outflow of foreign currency. Restoring public faith in the Afghani would be an essential step to restoring faith in the credibility of the central bank and in government institutions.

Tackling the currency issue from another means, I enforced a rule that all vendors that Canada dealt with had to acquire bank accounts. That would ensure electronic records of all our financial transactions occurring in Afghanistan. Again, I presented the policy to my troop-contributing nation partners and it was adopted by all. Prior to this, the government had no means of knowing how much vendors were making or what they were doing with the money. Black market activity was rampant. The existing banks in the country were all signatories to international anti–money laundering protocols. Protocols that provided a measure by which the Afghan government could now monitor suspicious transactions.

Enforcing the need for vendors and corporations to adopt bank accounts and allowing the government visibility as to how much the businesses were earning also gave the government a means to collect taxes. Vendors could no longer hide revenues. From a nation-building perspective, Afghanistan needed all the help it could get to monitor revenues and cash flow and create a tax base. Without the knowledge of who was making what, it would have been nearly impossible to collect taxes and ultimately fund government programs. They weren’t going to get much from poor farmers but there were corporations making lots of money in Afghanistan and, from my perspective, they should have been paying their share of taxes to help the country rebuild.

The adoption of bank accounts by our vendors also made life a little safer and more secure for Canadian troops and the Afghan vendors with whom we interacted. By using bank accounts, we didn’t need to physically transfer millions of dollars of cash to pay a vendor. Transactions could now be done electronically and safely, with the government having oversight and reducing black market activity.

Once both policies were adopted, nearly 80 per cent of all payments effected in Kandahar province by all troop contributing nations were in Afghani and were completed electronically to a bank account.

RICK GOODYEAR

There was so much we could do. The damage to infrastructure in and around Kandahar was not just a result of the fight against the Taliban under Operation Enduring Freedom. The bulk of the destruction had happened after 1992 when the pro-Soviet communist regime finally fell. At that time, all but one political party in the country agreed to share power and live in peace under the government of the Islamic State of Afghanistan, which was established by the Peshawar Accord of that year. The dissenter was Hezbi Islami, a party originally formed in 1975 and now subscribed to by many Pashtun students who had played a strong role in defeating the Soviets. They wanted an end to tribal rivalries and the establishment of a single non-ethnic regime. While these aims seemed identical to those of the government, Hezbi Islami reacted violently against the new Islamic State of Afghanistan. Between 1992 and 1996 they attacked government offices in and around Kabul. As Human Rights Watch has reported, “shells and rockets fell everywhere.” The result was a civil war that shook the country, and from which Kandahar eventually suffered more than any other city, becoming what the Afghanistan Country Study Guide called “a centre of lawlessness, crime and atrocities fueled by complex Pashtun tribal rivalries.”

Amid the chaos, warlords seized initiative in various parts of the country, paying for mercenaries, weapons and ammunition with the profits of poppy and marijuana production. They turned the civil war into a gangland turf war. Oddly it was their abuse of power—notably the systematic raping of children—that led another group of students, under Mohammed Omar, to form the Taliban and go after them. Once again, it was war. The destruction continued.

Mullah Mohammed Omar was a shy, quiet, private man. An ethnic Pashtun, he was born poor sometime after 1950 in Kandahar Province, in a village reported by many (but not all) to be in the Panjwayi District. Omar’s subsequent rise to leadership, power and celebrity gave his Panjwayi home special significance to his followers, in time distinguishing the area as the so-called heartland of the Taliban. Whether deserved or not, it led his disciples to a conviction that dying for their cause in Panjwayi would be selfless and noble, much as modern soldiers feel about sacrificing their own lives to save their comrades in arms. A more cynical view of the heartland theory holds that because Panjwayi land is fertile, it is therefore profitable. Most of the Taliban now own property there. Looking for the Taliban? Follow the money.

It’s tough for westerners observing the atrocities of the Taliban to comprehend how such perversion of logic could attract any followers at all, let alone the tens of thousands who have sacrificed their lives to the cause. The secret may lie in the Taliban’s distinct approach to the provision of security services, and to appreciate that you have to understand zakat.

In Islamic tradition, zakat is a form of tithing by which the faithful share their wealth with others. As one of the Five Pillars of Islam, zakat is considered in many nations to be a sacred and purifying obligation rather than just a personal act of charity. The amount given to the community depends on each person’s income and total wealth, and is typically calculated as a percentage, often 2.5 per cent or one-fortieth of someone’s total situation. The Taliban were well aware of the exact percentage members of each community were comfortable paying. When they demanded payment for security, they set their protection fee no higher than that familiar percentage, knowing it would at least appear as reasonable. They then protected their new clients by intimidating any would-be aggressor. In great part, that’s why the Taliban are tolerated.

Local government leaders, corrupt members of the Karzai government, and warlords might say, “We’ll do your security for 20 per cent,” or perhaps 15 per cent, but in any case at a much greater rate than the Taliban ever did. The Taliban did everything consistently with the religious norms and cultural experiences of the Afghan people. That’s both how they recruited and how they swayed people with an alternative view, saying, “Hey, NATO can’t secure you, and the Afghan government can’t secure you, and most of the Afghan army and the Afghan police can’t secure you, but we can. We’ll fight for your tribe, protect you against the other tribes, and we’ll do that for only the amount you’re already paying at the mosque.” Given that argument, if you were someone in that situation wouldn’t you be more likely to trust somebody who speaks your language, lives amongst you, practises your religion, is culturally adept at interweaving themselves into your society? Or would you be inclined to trust some other guys from the outside that are very foreign to you? Remember these are people with a 22 per cent literacy rate. We in the West don’t fully appreciate the power of education. Sitting in shuras [decision-making sessions] on mountaintops with some of these Afghan people, we saw them react to a helicopter, a jet airplane, an armoured vehicle from Canada as something from outer space. If you’ve lived with a wheelbarrow and a hoe most of your life, even a bulldozer showing up in your area will seem extremely foreign. But when you look at a guy walking into your village with an AK-47 and a blanket, wearing the same hat you wear, speaking your language, you will be more drawn to that person, even if he’s a Taliban. It’s an issue of trust following familiarity.

The worst form of leadership is intimidation, and it’s practised brutally by the Taliban. By the late 2000s the Taliban were taking women who had been raped into soccer stadiums, tying them to posts and publicly executing them in front of 8,000 people for being promiscuous. If you did not conform to the Taliban way, you were going to be treated with the most extreme forms of violence, and that served as a deterrent to the rest of the population whom they wished to control. But people have short memories. By the mid to late 2000s people had forgotten. That’s true even today. People make trades. Who do they think is the better angel to engage: the Taliban or coalition forces? That depends on how they’ve been treated themselves.

BEN FREAKLEY

A casual look at a fundamentalist, fanatic, misogynist regime that has routinely stoned women to death for adultery, beheaded enemies, armed children with explosive devices, dragged farmers in front of firing squads for “colluding” with the government, and who famously allowed Osama bin Laden to operate his Al-Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan and then refused to turn him over after 9/11, will inspire little sympathy. While the lazy conclusion that the Taliban are just evil is momentarily satisfying, it is unhelpful in the long run. While power routinely corrupts, the corrupt seldom achieve power through brute force alone. They either start out with a sincere vision of a better future that appeals to the masses, or they fake it. In Mohammed Omar’s case, the original call to arms was made in reaction to widespread abuse of the Afghan poor by the opportunists who seized power in the vacuum created when the Russian invaders were finally expelled from Afghanistan in 1989.

Seventeen years later, we were there to help clean up the mess.

In the tenuous stability made possible by NATO intervention after 2004, our coalition of thirty-seven NATO nations had agreed that provincial reconstruction would be part of every campaign plan. We had to help the country rebuild its infrastructure. Leading RC South, Canada would have the job of making that happen around Kandahar. We knew that mission success would depend on far-reaching development activities as well as kinetic operations. So when we put together the Canadian team for Afghanistan in late 2005, I asked Rick Hillier to get me a policy advisor and a development advisor from Foreign Affairs. That seemed to me in line with the whole-of-government approach prescribed by the Canadian government itself. Rick set up a meeting, and I came in to brief Foreign Affairs on our campaign plan. Then I asked for their help. They did not look happy about that, and I sensed that interdepartmental collaboration was neither a strength nor an interest. Once again I asked for a policy advisor and a development advisor. We got the first in Pamela Isfeld. We did not get the second.

Without a policy advisor, we would have been hamstrung. With our deliberately chosen approach, we had to advance ambitious plans on three fronts at once: defence, diplomacy and development. So when Pamela joined she was bolted right into our day-to-day operations, providing the context and expertise we needed to collaborate with the political world. She helped balance the interaction between us and Foreign Affairs, National Defence and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), and became an important interface for the teams from other nations working in RC South. Pamela is a professional of great humility. Working with us she had to be; she got no special treatment, was quartered in the most modest digs imaginable, wore the same heavy and hot protective gear we all did, rode overland in dusty vehicles, walked on long patrols, and sat for countless meetings with Afghan authorities to help build relationships. She dug into her duties like a trooper, which everyone appreciated, and she had a solid sense of humour, which she often needed. I recall visiting Governor Armand in Zabul Province and taking Pamela along. Armand was a marvellous man—one of the best leaders Afghanistan has produced. He was walking us through a market in Qalat and, as we were strolling, casually grabbed a scarf for Pamela and said, “A gift from us.” While our Afghan hosts never forced their culture on us, there was an unspoken hope that when out among the people whose help we relied on, we would be sensitive to the context. Pamela didn’t miss a beat; she accepted the governor’s gift with a smile and cheerily put the scarf on her head.

Pamela’s role with us in the south of Afghanistan was new to Canada, and I felt for her as she worked out the arrangements with our ambassador in Kabul. Unnecessarily, Foreign Affairs had insisted that Pamela report back to them directly in Ottawa instead of to the ambassador—who, after all, was the head of mission. That made things awkward from time to time, but Pamela navigated those shoals and kept our work moving. We had the policy advisor we needed.

We still had no development advisor, however. When we arrived in theatre, we could see that the Americans were handling the development issue in their usual way, which was “big.” To manage reconstruction, they had put together a massive operation in which most U.S. government departments were represented in some way. The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) led the effort, and when the 10th Mountain Division opened a door for us to the vast U.S. resources supporting their work, we linked up with USAID immediately. But with no Canadian development advisor to run our operation, we simply couldn’t be effective even with their help. So we went on the hunt.

We had heard good things about a CIDA rep working out of Kabul named Christina Green. I reached out to her, and we had several conversations in which I proposed she come down and run things for us. She was a hard nut to crack; not easily convinced that we were ready to do big things, and even if we were she wasn’t sure how she would fit in. I said she would work with me and lead all the development work for our region. Still she was not convinced. Over time I was able to walk her through our well-considered campaign plan, which detailed an operation whose success depended as much on community reconstruction and development as it did on fighting the Taliban. Eventually, she agreed.

Christina was everything our team was looking for: inquisitive, energetic, thorough, professional and engaging. She was indispensable to our work. She knew everyone in the overseas development world, where a vast network of professional allies stood by to help her out. People respected and trusted her, and she made important connections for us with the provincial reconstruction teams (PRTs) in each of the other provinces, with national agencies such as USAID, and with the more than thirty organizations running development projects in the Kandahar area. She was good-natured and easy to work with, but in no way a pushover. She held her own against suits and soldiers alike, and she fought against bureaucracy both in and out of theatre. Because of Christina, we never got bogged down. We did a lot and we did it fast.

In the summer of 2006 alone, we authorized and spent around 30 million dollars on reconstruction and development, of which two-thirds was funded by the U.S. We had negotiated a deal with USAID and had ready cash for discretionary spending, as do all U.S. commanding officers in the field. No longer did we have to wait for funding to be approved in Kabul and to trickle down like molasses through the usual channels. Whenever I and all my captains, lieutenants and sergeants set out to meet with elders, we made sure to arrive with pockets full. Need a pump? We’ll fund that. Looking for a tractor? We have five outside. Trying to find something tougher to source? We’ll deliver it tomorrow. Building a new village market? Here’s two thousand in cash. At every turn, we proved that we were ready to work with them and that we could be trusted. We built relationships, and we showed them we knew how to do more than fire guns. And Christina ran it all.

We built schools, district centres and family dwellings, teacher training centres, hospitals and clinics. We dug 100 kilometres of irrigation canals, 150 kilometres of roads, erected four bridges, brought forty-two new generators online, dug 1,061 wells, laid 3 kilometres of water-supply pipes, ran sixteen vocational training courses and gave out 166 sewing machines and a large number of other tools.

With our growing knowledge of the needs of the locals, we knew what the priorities were. We were building, not killing. And every time we paved a road, we made it almost impossible for the Taliban to plant and hide IEDS in that road. Farmers could get their products to market, commerce could flow, people could get together to meet. With a secure road to travel and a district centre in which to gather, the three arms of Afghan civil society could get on with their business: the federal government with its money, the tribes with the people’s authority, and the security forces with their protection.

Admittedly the Taliban went to great efforts to destroy anything we built, but that backfired on them every time. We would just go to the community and say, “Look, we built that thing together and the Taliban destroyed it. Your issue is now with them, not us.” After these events it became apparent to each community that the Taliban was setting them back years in development. Meanwhile they saw firsthand the benefits of our help. Their teachers had had nothing but tents before; now they had schools, and literacy rates were climbing. They’d had to travel miles for medical treatment before; now they had clinics, and mortality rates were falling. Their children had been dying of preventable diseases before; now they were inoculated, and contagion rates for measles and polio were at an all-time low. Their crops had been rotting in the fields before; now there were roads to take their produce to market, and there was more cash in their pockets. Every time we did something together, it made a difference. And every time the Taliban ripped something down, they proved that their only interest was self-interest. Their claim to be the only protectors of the people had less and less effect.

Our medics were heroes every day. Their main task was to support our soldiers when the need was there. Tragically, they were some of the busiest people in Afghanistan. Everyone wanted to see them, knowing that they were there and that they were well trained, well equipped and supported by medevac and hospitals. With that knowledge, the men and women who went downrange threw themselves at every task knowing they would be cared for. Our medics also did a lot to help the local population. We often conducted medical outreach visits to villages. We would treat ill and injured Afghans either there in the villages or by taking them to our own hospitals. In this way we showed that we weren’t just talk—we were actively providing much-needed medical care that otherwise was not available. And we did our utmost to be culturally sensitive to the needs of Afghans. We enlisted the aid of female soldiers to augment our female medics as they gave medical assistance to Afghan women and children. In this way, we proved repeatedly that our value sprang from much more than just fighting.Credit 11

I am in no way holding up these results as some kind of long-term victory. A decade later, many of the villages we backed once again face conditions as bad or worse than they suffered then. The eventual failure of coalition nations to keep funding flowing provided fuel for the Taliban propaganda machine. In addition, in our efforts we made a fatal mistake by leading with the military instead of the police. The immediate advantages of that approach were obvious: whenever we did something for a community, they protected us from attack, either by refusing to help the Taliban or by tipping us off to a threat. But no one is ever truly comfortable with an occupying force, even when it’s there at the express request of one’s elected government. It is the police, not the military that communities associate with law and order, even when some members of that police force may be corrupt. We blew that, and by “we” I mean our regional command, our entire NATO coalition, and the government of Afghanistan.

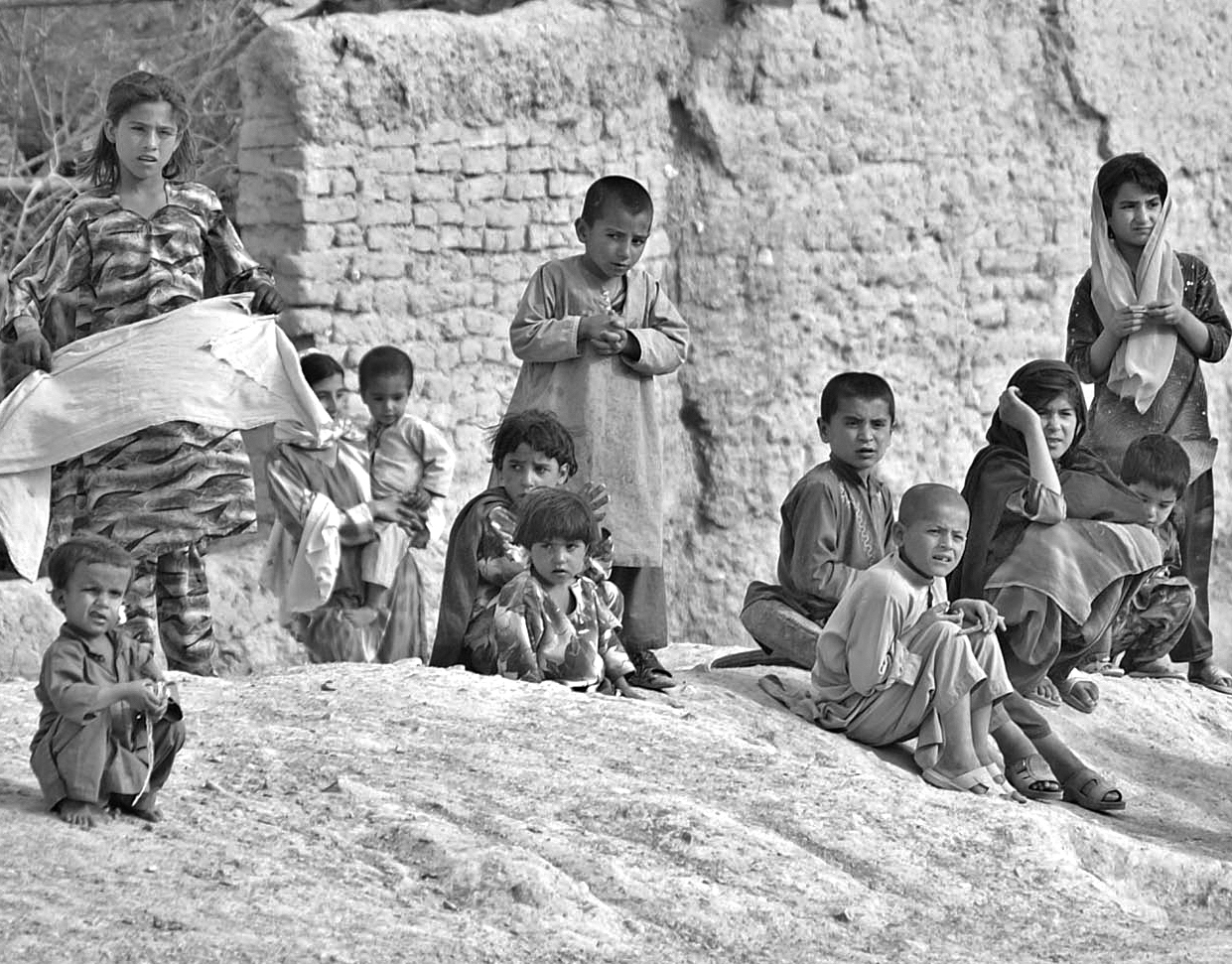

The children in Afghanistan were wonderful. They were inquisitive when we walked around, and soldiers always had pencils on them because that is what the kids asked for. Education was the key to success, and was fundamental to helping the Afghan people. The children wanted to learn, as did their parents. School supplies were the one thing we asked Canadians to send over. They were always well placed. The other thing we did when we were out there was to help children and women with medical outreach visits. When women turned up without their children, we feared the worst.Credit 12

But I remember doing one thing right. Having learned the value of partnerships while working alongside (but not directly in) NORTHCOM in Colorado Springs, I looked around in Afghanistan for as many partners as I could find. Sometimes, however, they just appeared. In mid-June, Rick Hillier and I were just about to fly from Kandahar down to Mirage air base near Dubai, when we received an invitation from Mohammed bin Zayed bin Sultan Al-Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi, to join him at his mother’s palace. His mother is Fatima bint Mubarak Al Ketbi, a vocal advocate for women’s rights in the Arab world and a champion of educational reform. Like his mom, Al-Nahyan is a social progressive with a passionate interest in education, economic development and environmental protection. He is also Deputy Supreme Commander of the United Arab Emirates Armed Forces. The Emirates already had a small team in Afghanistan, and the prince was eager to learn more about what was going on over there. So when he heard we’d be in the area, he asked us over. We accepted and headed to the palace a day or two later. We were warmly received, and as someone brought in coffee and dates, Rick sat on one side of our host and I sat on the other.

Being a soldier himself, the prince asked what we were up to. So I told a bunch of war stories that illustrated what we were doing over there. It was a grand old talk, just three soldiers chatting. At the end, he leaned forward and said, “What can I do for you? What can we, the Emirates, do for you?” I was floored and put slightly on the spot, but in a moment I suggested that assistance in reconstruction might be ideal. “You can put up mosques,” I said. Without radios and televisions, their mosques were the people’s only source of information beyond gossip. But many mosques had been damaged in the civil war, and most had not been repaired or funded since. “I can’t fix or build mosques,” I told him. “I’m a Christian, but if you could do some of that, starting with the main mosque in downtown Kandahar, you would probably be really helpful.” The prince just said, “Thank you very much for coming; it was a pleasure to see you,” and ushered us out. This time I knew I didn’t know what had just gone on. We headed back to Kandahar.

Two days later, three guys showed up in my office. Frankly, I don’t even know how they found it. They said, “We’ve been sent by the Crown Prince. We’re here to help you and we have a blank cheque to do so, but there are two conditions you must agree to. First, you may not tell anyone we’re here. We’ll just go about our business and do everything behind closed doors. We don’t want any recognition. Second, once we start, you’ll never hear from us again and you must not try to make contact.” Good opener.

I said I could do that. I then contacted the Governor of Kandahar and said I had some people wanting to talk to him about reconstruction. He said he’d invite the tribal elders. As soon as we walked in, they all looked at my guests and fell off their chairs. The U.A.E. has huge gravitas in the region, and the Emiratis had just shown up. They all fell to chatting, and at one point the Emiratis and the governor just kind of turned to me and said they would take it from here. I never contacted them again. But I knew I had played a small role in getting one regional power to help another in a useful way; bringing a solution to this horrid conflict closer than any gun ever could.

Later, after my tour in Afghanistan, I paid a visit to my former OEF commander Lieutenant General Karl Eikenberry, in Brussels. Karl asked, “What are you doing tomorrow for breakfast?” The next morning, he introduced me to Richard Holbrooke, a special emissary to Afghanistan sent by Barack Obama to figure things out. Holbrook asked, “What should we be doing in Afghanistan?” I didn’t hesitate. “Go get the Emiratis to help you. We can do a lot of stuff, but they can do it better. They think of the Afghans as brothers and sisters.” And then I paraphrased T.E. Lawrence: “It’s far better for people to do something imperfectly themselves than for anyone else to do something perfectly for them.”

I learned that in Afghanistan.