CHAPTER 10

ENGAGE

When we moved the Boss in the LAV, he just sat on an old box in the back. But we also had to take some shooters for protection, so we stripped out the main seats and added some swing seats for the guys. We also put in a coffee maker and a sandwich maker. We pimped his ride.

MOTHER

It was standard operating procedure that when we had troops in contact, I would be informed. I would then head to the operations centre in RC South, a plywood building adjacent to Kandahar Airfield that was part of our headquarters. This nerve centre housed the main elements of the formation, including our intelligence, planning, operations and command teams. The operations room was run by our chief of operations (CHOPS), Lieutenant Colonel Tim Bishop. A seasoned artillery officer, Tim was simply immune to stress. Never have I seen another person handle pressure and complexity with the poise and confidence that Tim displayed. The only indication I ever had from him that a situation had turned bad was his asking to speak to me in my office.

The tactical operations centre (TOC) was dominated by a wall of knowledge: a broad sweep of oversized computer monitors displaying Predator feeds, live charts tracking the locations of every unit and incident, dynamic checklists that kept us on track, and a seemingly endless stream of intelligence from other sources. Beneath this array of information stood two rows of desks at which men and women referenced individual computer screens as they interacted with troops in the field, our higher headquarters in Kabul and Canada, and the operations staff of other organizations. These were our liaison officers from all subordinate units such as 1 RCR, our flanking formations, and aviation, medical, logistics, legal, artillery, ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) and so on. We had people connected to every unit and enabler we controlled, cooperated with or reported to. And we needed every bit of it to maintain a high situational awareness and be able to respond to any event.

At the back of the room were several claustrophobically small offices, including Tim’s. As CHOPS, Tim was my minute-to-minute leader. He managed operations within the region day and night. Whenever there was an incident, he informed me immediately and, if necessary, I would come to the TOC to lead. There I had everyone I needed to give me the right information to make informed decisions and coordinate the fight. This was also the location from which we pushed assets to any affected “call sign” (our jargon for a unit or individual with whom we were in contact). It was in this room that I learned about Major Mike Wright’s engagement with a sizeable Taliban force south of M’sūm Ghar. Little did we know then that these fighters had come out of Sperwan Ghar just a little further south, which proved the build-up of enemy in an area other than across the river.

Mike and the company of PPCLI soldiers he commanded had been in Afghanistan since August 4, the day after three of their fellow Patricias had been killed in the ambush at the white schoolhouse. I had known Mike since 1997 when I took over 2 PPCLI. Mike was a platoon commander. I spotted him early on as someone worth nurturing. Technically competent, studious, understated and unflappable, he did everything asked of him without fuss or fanfare.

In Afghanistan, Mike’s A Company had taken responsibility for the districts of Zhari, Panjwayi and Maywand. They had been frequently ambushed along the main highway in the region and at Patrol Base Wilson in Zhari District. Their freedom of movement was therefore severely limited, which was frustrating as our concept of operations throughout the south relied on a maneuverist approach. We did not want to be fixed in any one location but did need to be seen by the people and provide a security bubble throughout our area of responsibility. Without enough troops to do this from static locations, we had to move around. By doing this we increased the effect that our troops on the ground could achieve. This concept of operations had been pioneered by the Australians in Vietnam where, by refusing to be fixed to bases, they could patrol large regions more effectively. We did the same. Not ideal, but that was our reality. In a sense we were spinning plates; whenever a plate started wobbling, we would get it spinning again, then move to the next wobbling plate.

We used forward operating bases as staging areas for our maneuverist approach. These FOBs allowed us to position our supplies forward, carry out maintenance and allow our troops to rest. We were frugal about how many of these bases we operated, but we did need some to cope with the enormous lines of communication we had to maintain. We had set up FOB Martello just east of Gumbad for precisely this reason. Martello helped us establish a presence in the northern part of Kandahar Province, and served as a staging site for the Dutch who deployed to Uruzgan. We had other FOBs throughout the province. One was in the south near Spin Boldak. Patrol Base Wilson in Zhari District gave us a strong presence on Highway 1. Another housed the provincial reconstruction team in Kandahar.

Whenever we assigned one of our Canadian task force companies a region to patrol, it would be staged out of one of these FOBs, but never allowed to stay in an area for long. We moved soldiers around throughout their tour so that they would stay sharp and not get too complacent in any one area. Combat operations also necessitated that we rotate troops so as to not overly tire out any one company in intense operations. This philosophy was embraced across RC South, particularly by the British in Helmand and the Dutch in Uruzgan. Other parts of the region were covered by the U.S. special forces with their own unique protocols.

But back to Mike Wright and A Company. As part of the handover from Task Force Orion to Task Force 3-06, Ian Hope had taken Omer Lavoie and Mike to the district centre in Bazar-e-Panjwayi, a major market town just north of M’sūm Ghar. There they had met the head of an Afghan special police unit by the name of Captain Massoud, one of Asadullah Khalid’s boys. Captain Massoud ran a special team that reported directly to Khalid and functioned as the governor’s mini-militia unit. He also worked closely and openly with the Canadians. We grew to admire him.

When Mike met Captain Massoud again on August 19, the day of the transfer of command ceremony from Ian Hope to Omer Lavoie, Mike reported that A Company had lately observed increasingly intense firefights along the high features of M’sūm Ghar from their position up at Patrol Base Wilson, five kilometres to the north. On the previous night, as journalists filed their stories from the internet tent at the patrol base, A Company had noted significant fire to the south, with tracer rounds clearly visible in the night sky. This was new. At 0200 a rocket screamed over the base, narrowly missing its intended coalition target. Clearly, the Taliban were itching for a fight.

Massoud confirmed that his officers were well aware of the activity. Taliban fighters had been exchanging fire with contingents of both the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police and were doing so at M’sūm Ghar as they spoke. Massoud himself would be heading back there that very day. Mike was quickly deployed with A Company to M’sūm Ghar that afternoon. There he could reinforce the Afghan troops who were taking the heat on the east side of the mountain.

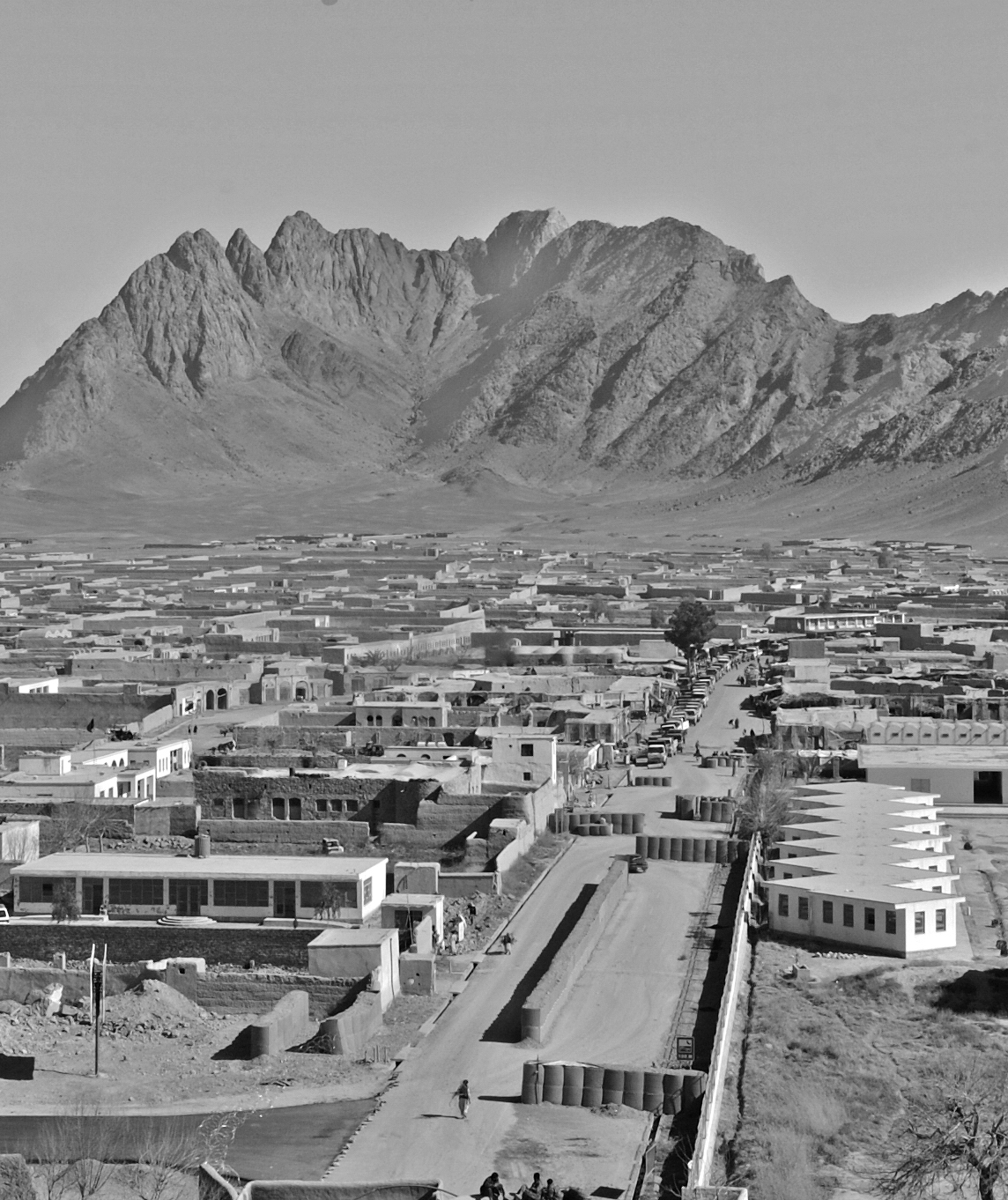

Bazar-e-Panjwayi is a small community just to the west of Kandahar City. Typical of an Afghan community adjacent to any city, it comprises a market and town centre and is associated with one of the hundreds of tribes in the region. Families usually live in communal home compounds. A compound will have a wall around it with several dwellings inside. The outside will be nondescript but inside the homes are adorned with colour. Children often played outside and there was a sense of normalcy that defied the dangers lurking around the corner in the form of a suicide bomber, suicide vehicle or Taliban ambush. Soldiers had to keep their wits about them, not only for the sake of their lives but also those of the innocent people in places like Bazar-e-Panjwayi.Credit 19

The Afghan National Army (ANA) was the only truly national force in Afghanistan. It comprised soldiers from every region and every tribe, and they deployed all across their country. They had been fighting for years against the Taliban. While lightly equipped compared to us, they were equally equipped to the Taliban and over time became better equipped. And the Afghan people generally had a good impression of the ANA, unlike the Afghan National Police (ANP). When we arrived, however, the ANA varied hugely in capability. This was in large part due to inconsistent leadership, and this was an issue we made sure to address. We always paired up with an Afghan unit, and operated with them for the most part. We attempted to put them first. Despite this, the usefulness of the ANA during our operations was limited at best. There were exceptions of course, and the ANA matured during our tenure. I visited the region two more times after my tour, and I was very much impressed with the progress and improved capability of the ANA.Credit 20

Mike remembers the event in detail:

I left a platoon to remain at Patrol Base Wilson to secure the Zhari district centre there. I was uncertain how much space there actually was in M’sūm Ghar, so I gave orders for 3 Platoon to deploy with me, my artillery forward observation officer and my LAV captain, and I put 2 Platoon on standby to come down to Panjwayi once I assessed the situation.

As I was the only one who had previously been in the area of Bazar-e-Panjwayi, I led the convoy of five LAVS and three jeeps myself past the town and out to M’sūm Ghar in the late afternoon. The road leading from the district centre to the mountain was narrow, very narrow. Halfway through, the back wheels of my LAV slipped down into a wadi. Eventually all our vehicles made it around, and I gave initial orders where to position them before I went to meet with Captain Massoud.

Massoud was quite a character, identifiable in the field not by an Afghan security forces uniform but rather by his Dolce & Gabbana hat and the designer walkie-talkie he used to communicate with his forces. When I arrived, he pointed out the positions of his men and some observation posts on the high ground, and we spoke about where he thought the main Taliban thrust was coming from.

We could hear gunfire in the grape fields to the south, but Massoud wasn’t concerned. I assigned the best vantage point to my forward observation officer, because what I was really hoping to accomplish was for him to be able to observe what we believed was the origin point of the mortars and rockets that had been harassing us throughout the month, and then to neutralize them.

I placed 3 Platoon in an open area and instructed them to link up with the Afghan police who were sprinkled around the position. Finally, I instructed my LAV captain to go back around the bend of M’sūm Ghar to watch our six o’clock and to secure the route to the district centre. I then sat down on a rock to write confirmatory orders.

Five minutes later I heard a pop and looked up. A rocket-propelled grenade was heading right for me. It landed some ten feet behind my position but did not detonate. Lucky. The RPG had been fired from the high feature, which was now occupied by figures in black clothing. Machine-gun fire and RPGs continued to be directed toward us. A number of Afghan police then ran down the embankment toward 3 Platoon. To this day I credit the strong discipline of my soldiers for not firing on them by mistake. Clearly the fight was now on.

We had arrived in M’sūm Ghar just prior to a major attack by the Taliban, who were likely aiming to seize the high feature and then overtake the district centre itself. As 3 Platoon had almost no time to prepare, their soldiers took cover in the LAVS and behind whatever structures they could find. The platoon then fought the insurgents for three straight hours. The size of the force that attacked us is uncertain. The Governor of Kandahar said later it had been around 400 fighters, but Afghan math is not an exact science. The total was more likely somewhere between 100 and 150 men.

Luckily my LAV captain Mike Reekie had gone a little bit further than the 200 metres or so behind me I’d assumed he had. When he got there, he realized he couldn’t see beyond the rise and advanced 200 metres more. He still couldn’t see, so he moved still further, ending up on a rise close to the Taliban attack position. There he observed successive groups of eight to ten Taliban dressed in black crossing the road to scale M’sūm Ghar yet again and continue the assault in the last light of day. We engaged them.

Realizing that his viewing attachment wasn’t working, Mike’s driver Corporal Chad Chevrefils popped open his hatch in order to help identify targets.

What that LAV crew did that night was absolutely pivotal. Displaying superb judgment, Mike and “Chevy,” as we called him—along with Mike’s crew commander Sergeant Dan Holley—assessed the changing tactical situation and constantly repositioned their vehicle to maximum advantage, enabling the interception and defeat of a numerically superior enemy force during the ensuing firefight. Their outstanding initiative prevented the enemy from outflanking our position. Both later received Canada’s Medal of Military Valour for their bravery, and the rest of the crew were mentioned in dispatches.

As Mike Reekie sent reports back to me about the size of the attacking force, I relayed that information to our commander back at Kandahar Airfield. Given the strength of the attack, he asked whether we needed reinforcements or even if we wanted to consider withdrawing. The answer to the first question was easy. Given the difficulty we’d had coming onto the position during the day, the limited space and the chaotic situation, I recommended against sending reinforcements. The second question was more difficult. On one hand, it was the beginning of the tour. The battlegroup was just starting operations, and we were in a pretty fierce fight against a much larger enemy than we’d expected. On the other hand, and I have to be perfectly honest here, we had a lot of regimental pride. We were a PPCLI company working with an RCR battalion. As long as I judged we could handle the fight, there would be no way we were going to pull off of that position.

After a couple of hours, we started to run low on ammunition, so I called 2 Platoon forward from Patrol Base Wilson to conduct ammunition resupply. With the fighting dying down, we then made a plan to pull off of the position and link with them in Bazar-e-Panjwayi.

Direction came to coordinate our withdrawal with the Afghan National Police. Given that I’d been in the LAV on the radio directing the fight and trying to assess the situation, I hadn’t paid attention to what our Afghan allies were up to, but it turns out they’d already pulled out of the position back toward the district centre.

Finally, when it came time to withdraw to regroup and refocus our forces, 3 Platoon’s G-wagens (the short form of the German Geländewagen, meaning cross-country vehicle) wouldn’t start. As a few remaining Taliban positions were still firing at us, the situation was tense. Yet Warrant Officer Mike Jackson and Master Corporal Paul Monroe ran the operation with cool heads, as their subsequent Medals of Military Valour attested. Fully exposed to the violence of the enemy, they got our personnel and damaged vehicles out of there. Their heroism under constant fire enabled us to regroup and continue the fight, while denying the enemy any chance of capturing and making use of our stricken equipment. We eventually withdrew from M’sūm Ghar and linked up with 2 Platoon. Thanks to a Predator strike, they had themselves narrowly missed being ambushed on their way into town. They then conducted an ambush of their own on a Taliban reinforcement party.

We were redistributing ammo when the order came to move toward contacts close to the river. I’d been down that route briefly in the daylight and was uneasy about moving along such a narrow road at night. Sure enough, as we moved in, one of the LAVS flipped onto its side. As a section dismounted from the vehicle to assess the situation, machine-gun fire sprayed down on us from a few hundred metres away. We responded, neutralizing those who were firing at us. Even as we did that, we received more reports of contacts closer to the river and began to get a picture of a very large Taliban force. As Sergeant Vince Adams was leading the operation to get the LAV back on its wheels, I assessed the situation. It was precarious, in part because of the terrain, in part because of our uncertainty about the size and the disposition of the enemy, and in part because we’d already been fighting in darkness for several hours. With Omer Lavoie’s agreement, we withdrew to the outskirts of town.

As dawn was breaking, we received orders to go back to the district centre to help evacuate some Afghan police casualties. I went in with a couple of vehicles and it was eerily quiet. We saw Taliban bodies lying in the middle of the street, some with sheets over them, some uncovered. If it’d been later in the tour, I would have realized how rare it is to see a Taliban body at all; they always recover their dead quickly. We moved slowly past them, then linked up with the Afghan National Police in the district centre. They loaded their walking wounded into trucks, and we escorted them into Kandahar City.

The next day, the Globe and Mail reported that seventy-two Taliban had been killed.

MIKE WRIGHT

Of all the company commanders in our task force, Mike Wright was the best. Gifted with a tactical touch, he undertook his duties with a rare and powerful combination of knowledge and instinct. His leadership in Afghanistan set the standard to which all other officers aspired. Great credit too goes to the men and women of the Royal Canadian Regiment, who welcomed Mike and his team so openly. Without doubt, our battlegroup commander Omer Lavoie and his regimental sergeant major, Chief Warrant Officer Bobby Girouard, deserve credit for ensuring that regimental differences would play no role in the battalion and in the operation. Together they set a tone of open collaboration that created one team and one team only. We all play for Canada.

With the full support of the larger battlegroup, A Company was able to conduct extremely successful high-intensity combat operations over the first three months of the tour, and also to ratchet down to focus on the critical activities of capacity-building and reconstruction. On August 19 and 20, the 126 soldiers of A Company had represented their battalion and their regiment well. Within two weeks, they would be called upon to do so again under even greater pressure.

Mike Wright (top centre, holding the A Company pennant) joined the 2nd Battalion as a lieutenant and was immediately spotted as an officer with potential. He was commanding A Company with 2 PPCLI when he was attached to 1 RCR for Afghanistan. I credit Omer Lavoie and his command team for making the integration into 1 RCR as easy as possible for Mike and his company. Mike’s own personality made this possible too. Mike is a quiet and highly proficient officer with a wicked sense of humour. He can be tough and funny when the situation requires. It was a pleasure to see Mike again and watch his stellar performance in Afghanistan. Mike’s first engagement, days after arriving, occurred south of M’sūm Ghar where he bumped into a sizeable Taliban attacking force. The gun battle that ensued lasted hours until Mike was able to defeat them. Mike received the Medal of Bravery for his actions during this opening battle, which was a fitting testament to his amazing leadership skills.Credit 21